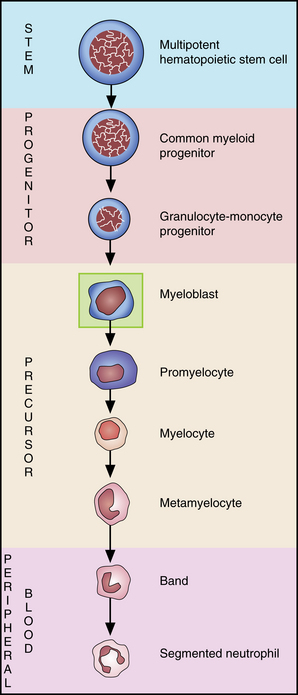

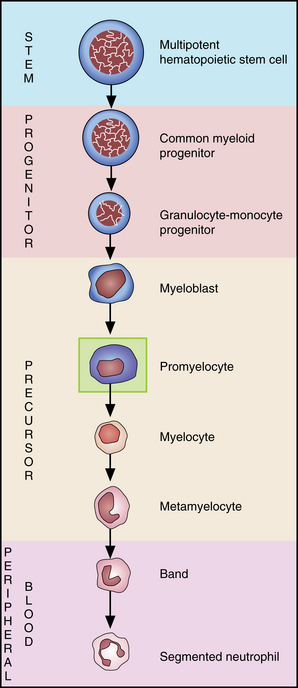

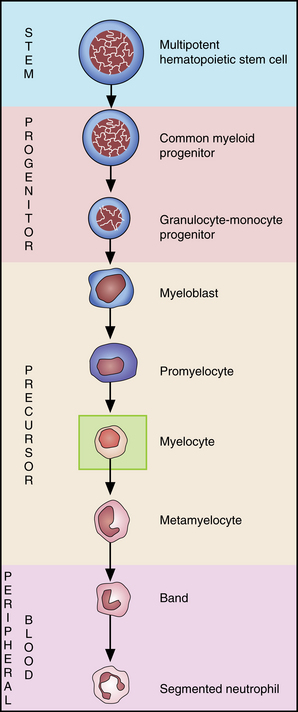

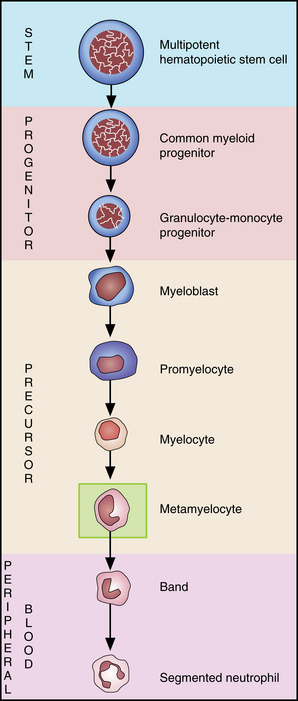

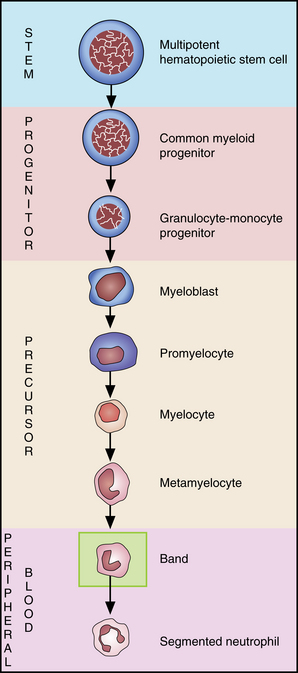

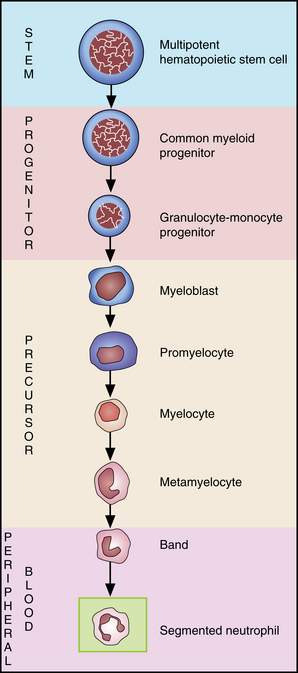

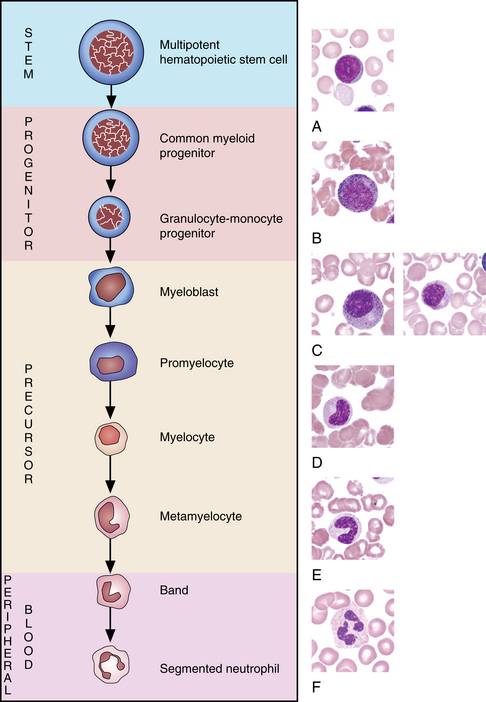

5 Neutrophil maturation

The common myeloid progenitor creates three types of progenitors: granulocytes/monocytes, eosinophils/basophils, and erythrocytes/megakaryocytes. Each of these divides and matures into cells known as blasts, one for each cell line. It is not possible at the light microscope level, however, to differentiate the various blasts. This chapter addresses neutrophil maturation. (See Chapter 7 for discussion of eosinophils and Chapter 8 for discussion of basophils.)

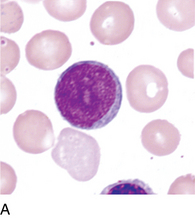

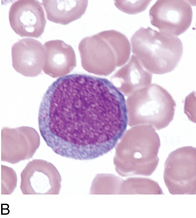

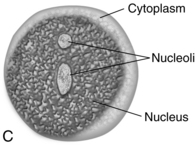

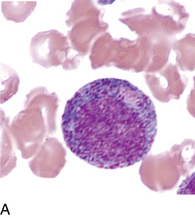

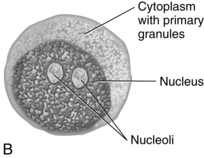

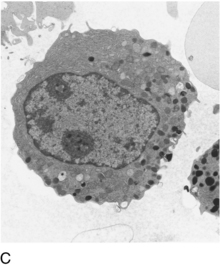

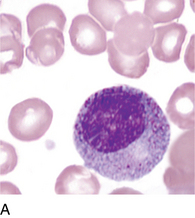

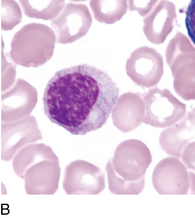

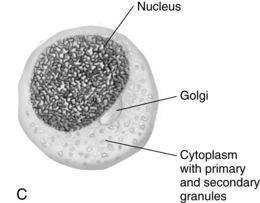

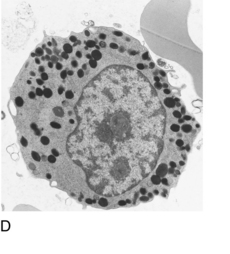

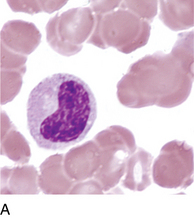

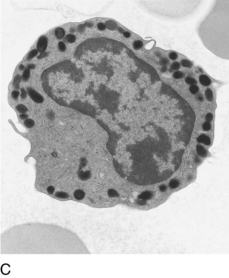

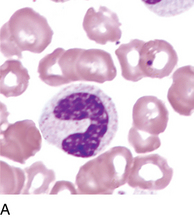

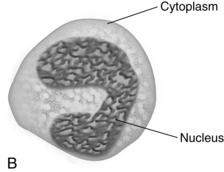

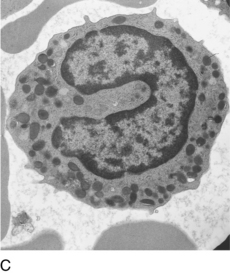

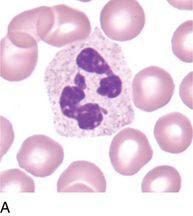

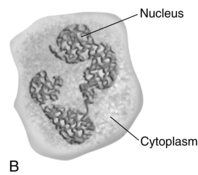

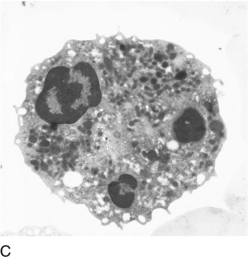

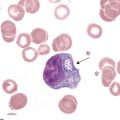

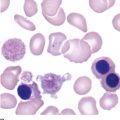

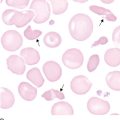

As the cells mature from the myeloblast to the promyelocyte, there is a slight increase in size, in contrast with size variation in other cell lineages. At the promyelocyte stage, the chromatin in the nucleus becomes slightly coarser than the myeloblast and primary burgundy-colored (azurophilic) granules appear in the cytoplasm. As the cell divides and matures to a myelocyte, chromatin becomes more coarse and condensed, and secondary (specific) granules appear in the cytoplasm beginning at the Golgi apparatus and spreading throughout the cytoplasm. Primary granules are still present but less visible on Wright stain because of a chemical change in their membranes. It is often possible at the myelocyte stage to see the area of the Golgi apparatus, which appears as a clearing close to the nucleus. The specific secondary granules differentiate the cell into neutrophil, eosinophil, and basophil. The nucleus then begins to indent and chromatin becomes coarser, signaling the metamyelocyte stage. In the metamyelocyte, the indentation of the nucleus is less than 50% of the hypothetical round nucleus. The cell is called a band when the nucleus becomes constricted without threadlike filaments and the indentation of the nucleus is more than 50% of the hypothetical round nucleus. Finally, the cell becomes a segmented neutrophil when the nucleus becomes segmented or lobated into two to five lobes. The lobes are connected by threadlike filaments with no chromatin visible in the filament. There is so much variability in the differentiation of band neutrophils from segmented neutrophils that the College of American Pathologists does not require that they be differentiated for proficiency testing.*

Segmented neutrophil

Polymorphonuclear neutrophil

* The College of American Pathologists recommendations are available at: College of American Pathologists. Blood cell identification. In 2011 Hematology, clinical microscopy, and body fluids glossary. Northfield, IL, 2011, College of American Pathologists. Available at: http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/proficiency_testing/2011_hematology_glossary.pdf.