Chapter 146 Neurosurgical Management of HIV-Related Focal Brain Lesions

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection causes a disease of the immune system known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).1,2 Although the condition was initially described in 1981 by the manifestations of opportunistic infections in homosexual men, the term AIDS was not coined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) until September 1982.3,4

HIV infection progressively reduces the effectiveness of the immune system and leaves patients susceptible to opportunistic infections and tumors. HIV is transmitted through direct contact of a mucous membrane or the bloodstream with a bodily fluid containing HIV, such as blood, semen, vaginal fluid, or breast milk. This transmission can involve anal, vaginal, or oral sex; blood transfusion; contaminated hypodermic needles; exchange between mother and baby during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding; or other exposure to one of the above bodily fluids. AIDS is now a pandemic with more than 33 million people infected worldwide.5,6

Epidemiology

Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms occur in 30% to 50% of AIDS patients, and as many as 90% have evidence of CNS disease at autopsy.7–10 Approximately 10% of AIDS patients have focal CNS lesions that might serve as a target for a stereotactic biopsy.8,11 One third of these patients have not had prior manifestations of AIDS when they are referred for biopsy.

Intracranial disease is second only to pulmonary disease as a cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with AIDS.12,13 Of the approximately 10% of patients with focal lesions in the brain, 30% to 70% have Toxoplasma gondii abscesses, and another 15% to 30% have primary or metastatic CNS lymphoma.8,11,12,14–16 Although the incidence of toxoplasma abscesses has decreased in some studies with effective antiretroviral and antitoxoplasma therapy, the incidence of CNS lymphoma appears unchanged.17 The remaining 20% include a myriad of bacterial (e.g., Listeria, Escherichia coli), fungal (e.g., Cryptococcus, Aspergillus), and viral (e.g., HIV, herpes, cytomegalovirus [CMV]) processes that can manifest as focal lesions on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain.8,11,18 Even the often diffuse process of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) commonly presents as a focal lesion.15,18 Moreover, HIV-positive patients are also apparently susceptible to the same diseases as the HIV-negative population and, therefore, can have the usual primary and secondary brain tumors,8,10,15 as well as the vascular (hemorrhage and infarction) lesions that occur in the brains of AIDS patients and the 4% to 20% of biopsies from which no definite diagnosis can be made. A comprehensive list of causes of focal brain lesions in HIV-positive patients is provided in Table 146-1. Furthermore, a few patients with AIDS have several CNS lesions of more than one etiology.11

TABLE 146-1 Etiologies of Focal Cerebral Lesions in HIV-Positive Patients

| Infectious |

| Parasites |

| Toxoplasma gondii |

| Cysticercosis |

| Fungi |

| Cryptococcus |

| Candida |

| Histoplasma |

| Coccidiodies |

| Aspergillus |

| Mucor |

| Escherichia coli |

| Bacteria |

| Mycobacteria |

| Listeria |

| Nocardia |

| Salmonella |

| Spirochetes |

| Viruses |

| Cytomegalovirus |

| Herpesviruses |

| Varicella zoster |

| Papovavirus |

| Noninfectious |

| Neoplastic |

| Lymphoma (primary and secondary) |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Glioma |

| Metastatic carcinoma |

| Other∗ |

| Vascular |

| Infarcts |

| Hemorrhage |

| Nondiagnostic |

∗ There is no reason to believe that HIV-positive patients are not susceptible to the same neoplastic brain diseases as the rest of the population.

Modified from Levy RM, Bresdesen DE, Rosenblum ML: Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): Experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 62:475-95, 1985.

Patient Considerations

Despite incubation periods of up to, and possibly greater than, 10 years, as well as recent advances in treatment, AIDS remains an imminently fatal disease.19–22 The CNS has been identified as one of the reservoirs for HIV that makes its eradication from the body elusive, despite highly effective therapies.23,24 Nonetheless, potentially effective therapies exist for approximately 90% of the identifiable causes of CNS disease in patients with AIDS.8,13 This fact suggests the usefulness of brain biopsy in the diagnosis and treatment of AIDS patients with focal brain disease. Because stereotactic biopsy is diagnostic in up to 96% of AIDS cases,15,16 and because almost all treatable AIDS-related focal brain lesions do not require resection, there is virtually no need for an open procedure, except in rare cases of impending herniation due to mass effect. Furthermore, stereotactic biopsy is a low-risk procedure,15,16,18 even in severely medically compromised patients (e.g., many of those with AIDS), because it can usually be performed with the patient under local anesthesia.1 A need for definitive diagnosis and low risk to the patient are persuasive in the decision to undertake an invasive diagnostic procedure. On the other hand, the communicable and fatal nature of HIV greatly compounds this issue and raises the questions of risk to those performing the procedure and whether or not accurate diagnosis and treatment have an effect on outcome. Questions such as these have inherent ethical overtones, but some, and possibly tenuous, scientific data on these issues are available to help in the decision-making process. Fortunately, the reduced incidence of opportunistic infections as a result of modern antiviral strategies has limited the surgeon’s exposure to such complex considerations.7,25

Risk to Surgeons Operating on HIV-Positive Patients

Solid data regarding the risk to surgeons who operate on patients who are HIV positive is scant and difficult to obtain. First, there is no way to be absolutely certain what other risk factors a given surgeon who contracts the virus might have and no way to be certain what operating mishaps, if any, can lead to transmission of the virus. In addition, more controversial issues, such as privacy, have an effect on the reporting of such data. Notwithstanding these issues, a few relatively scientific attempts at quantifying the risk of seroconversion (becoming HIV positive) in surgeons have been reported.26,27 Schiff, for example, formulated a mathematical model for estimating a given surgeon’s cumulative lifetime risk.26 The model accounts for seroprevalence in the patient population; the inoculation rate, roughly based on surgical subspecialty; and the estimated probability of infection for a given procedural mishap. One survey estimated a greater than 6% 30-year risk in the 10% of surgeons considered at highest risk.27 Even if estimates of a surgeon’s risk of contracting HIV are of questionable accuracy, existing evidence raises the possibility of some risk, and any risk of contracting a fatal disease must be considered.

Preoperative Evaluation

Radiographic Studies

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid 1990s, the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV-1 infection has significantly decreased and AIDS has become a chronic disorder.28 Accurate diagnosis and treatment of brain lesions in HIV-infected patients affects outcome, and given even the slightest risk of disease transmission during an invasive procedure, the question arises whether the diagnosis can be made noninvasively. Although radiologists have reported an ability to make some diagnoses confidently on routine neuroimaging studies (CT and MRI), the consensus has been that the definitive diagnosis must be made histologically.7 Dina, for example, found that if a mass in the brain of an HIV-positive patient enhanced, was unifocal, exhibited subependymal spread on CT or MRI, and was hyperdense on CT without contrast, it was never toxoplasmosis in his series of patients.29 However, he still recommended that these lesions undergo biopsy.29

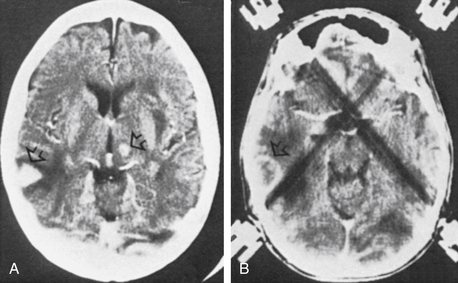

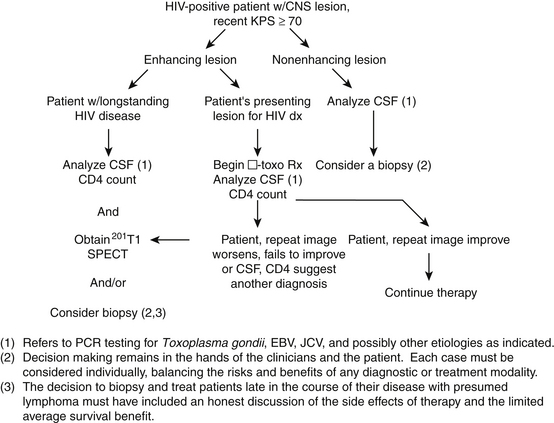

Since then, other investigators have delineated a wider spectrum of CT and MRI findings for lymphoma, cautioning against confident radiographic diagnoses.30 Some authors have suggested that metabolic imaging (positron-emission tomography [PET] and single photon emission computed tomography [SPECT]) make it possible to distinguish between malignant and nonmalignant lesions.31,32 In fact, thallium-201 SPECT is more than 90% accurate in distinguishing between tumor (especially lymphomas) and infection,32 although its value in the presence of HAART appears reduced.33 Despite eloquent attempts to characterize the various brain lesions seen on neuroimaging studies in HIV-positive patients, no constellation of findings is 100% diagnostic of any of the numerous disease entities.34,35 Moreover, the possibility of numerous etiologies for several brain lesions cannot be ignored in these patients (Fig. 146-1).

Empirical Therapy

At best, neuroimaging is suggestive in the diagnosis of AIDS-related brain lesions. This does not mean, however, that one should proceed directly to brain biopsy. As noted earlier, most focal brain lesions in HIV-positive patients are T. gondii abscesses, which generally resolve when the patient is treated with adequate doses of sulfadiazine (or clindamycin) and pyrimethamine (anti-Toxoplasma therapy).36,37 Rosenblum and associates thus proposed that stable HIV-positive patients with several lesions on MRI receive 2 to 3 weeks of empirical anti-Toxoplasma therapy.38 If follow-up images and physical examination fail to show improvement, these authors then recommend biopsy. This regimen appears prudent, and although up to 40% of patients cannot tolerate the therapy, leading to inadequate treatment and often to biopsy, the incidence of toxoplasmosis in biopsy series is decreasing.15,16,18 The algorithm should probably be extended to include any HIV-positive patient with one or more contrast-enhancing lesions on CT, because cerebral toxoplasmosis is not always multifocal.15 In addition, deterioration in a patient who is on anti-Toxoplasma medications might warrant early biopsy.

Laboratory Evaluation

Rosenblum and colleagues38 also suggested that in the absence of mass effect, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be evaluated in HIV-positive patients with focal brain lesions. However, sensitivity and specificity for most causes of HIV-related focal lesions is less than optimal.37,39–42 Only a few patients with lymphoma have abnormal CSF cytology, for example.39,41 However, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may be a marker in the CSF for primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL). The assay for EBV in the CSF requires gene amplification (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]).43,44 Furthermore, although the CSF is abnormal in toxoplasmosis patients, the findings are nonspecific.37 In serologic tests (whether on the blood or the CSF), as expected, antibody titers are unreliable in immunocompromised patients.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

In recent years, the analysis of CSF in patients with HIV disease has been revolutionized by the advent of the PCR technique, reducing the need for brain biopsy.25,45 Even minute amounts of DNA from various viral and bacterial particles can be detected in the CSF using PCR. JC virus (JCV, associated with PML), herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), CMV, EBV (associated with PCNSL), T. gondii, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis have been detected in the CSF of HIV-positive patients. Threshold levels for detection of many of these antigens have now been defined.46 Furthermore, the technique may be used in certain cases to monitor the efficacy of treatment or the progression of disease.47,48

Antinori and associates analyzed the CSF for EBV, JCV, and T. gondii by PCR in 66 of 136 HIV patients with CNS lesions. Patients in whom anti-Toxoplasma therapy had failed also underwent stereotactic biopsy. These investigators found that if EBV DNA or T. gondii DNA tests were positive, the probability of PCNSL or toxoplasmic encephalitis, respectively, exceeded 0.96.49 On the other hand, the absence of T. gondii DNA positivity in the CNS does not rule out the diagnosis of toxoplasmic encephalitis.49,50 The same is true of bacteriologic examination of the CSF for tuberculosis.51 Others report less sensitivity.52 More recently, Portolani and colleagues reported data that cast doubt on the role of EBV in HIV-related CNS disease.53 Nonetheless, lumbar puncture can provide enough diagnostic certainty to treat a patient without a histologic evaluation of tissue obtained by biopsy.

Surgery

If unable to make a confident diagnosis by noninvasive or minimally invasive means for an HIV-positive patient who has a focal cerebral lesion that has not responded to anti-Toxoplasma therapy, a biopsy must be considered. Such a measure is taken if the clinician and the patient and ultimately the surgeon agree that the risk of achieving a definitive diagnosis is outweighed by the potential for improving outcome. Chappell and colleagues reported their experience in the management of HIV-related focal brain lesions in an attempt to define the role of brain biopsy15 and developed an algorithm that minimizes unnecessary risk to patients and surgeons. Decision making and the application of such an algorithm can be further refined by the use of PCR analysis of the CSF.

Surgical Technique

CT-guided stereotaxis was used for all patients in the series. Single- or double-dose administration of intravenous contrast material with and without delayed image acquisition was used. De La Paz and Enzmann suggested that a double-dose delayed-contrast CT provides the best results,54 but MRI is still more sensitive and possibly more specific in the differential diagnosis of HIV-related brain lesions.33,35,54,55 If a compatible stereotactic system is available, MRI guidance is a suitable alternative to CT. The efficacy of an ultrasound-guided technique merits its inclusion as a suitable alternative as well.42 However, this procedure involves a more-involved surgical opening and thus possibly an increased risk to the surgeon and the patient. The availability of frameless stereotactic systems allows the minimal invasion of a twist-drill or bur hole procedure without the discomfort of a headframe.

If several lesions are present, either the most accessible cerebral lesion in the least eloquent brain or a lesion not responding to therapy is selected. In general, specimens are taken from only one lesion, but the occasional case warrants targeting more than one lesion (see Fig. 146-1). Target sites are chosen at the center of nonenhancing or homogeneously enhancing lesions and at the hyperdense border of ring-enhancing lesions.

Specimens are given to the pathologist for intraoperative smear cytology and frozen-section histology as needed. This process is repeated until diagnostic or clearly abnormal tissue is acquired. One or more additional specimens are sent for routine histology and transmission electron microscopy. A Gram stain and bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures and stains are obtained. Levy and colleagues13 reported that the diagnostic efficacy of brain biopsy in HIV-related brain lesions can be elevated to 96% through the use of these and various immunohistochemical techniques performed on at least six tissue samples.

Results

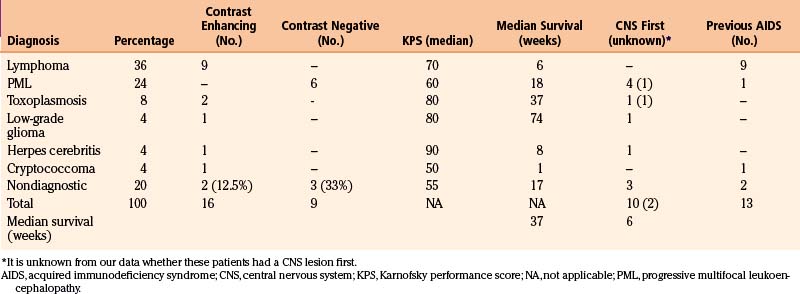

The records of 25 HIV-positive patients who were consecutively referred for biopsy of cerebral lesions at the George Washington University (GWU) Medical Center (Washington, DC) between November 1988 and October 1990 are reviewed. The preoperative characteristics of these 25 patients are shown in Table 146-2. It is notable that 13 of the 25 had been seropositive for HIV for a median of 34 months, and AIDS was diagnosed in these patients before they presented for brain biopsy. In the 10 other patients for whom this information was available, the cerebral lesion precipitated the initial presentation for treatment and the diagnosis of AIDS. As shown in Table 146-3, this distinction had great bearing on the median survival after biopsy in these patients. The patients who had previous AIDS-related disease had a considerably shorter survival time than did those who were found to be HIV-positive at the time of presentation for biopsy (6 vs. 37 weeks). Of the 13 patients with AIDS before their biopsy, 9 had lymphoma. Conversely, all patients with lymphoma had AIDS before their procedure.

TABLE 146-2 Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Stereotatic Biopsy of HIV-Related Cerebral Lesions at George Washington University Medical Center, November 1988 to October 1990, n = 25

| Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

| Male | 24 |

| Homosexual | 21 |

| IVDA | 2 |

| Haitian | 1 |

| Female | 1 (IVDA) |

| Age | Mean, 36 yr: range, 21-53 yr |

| Known to have AIDS before biopsy∗ | 13 (for a median of 34 mo) |

| CNS lesion prompted diagnosis of AIDS | 10 |

| Karnofsky performance score | 65 (range, 40-100) |

| Median follow-up† | 8 wk |

| Dead | 17 |

| Lost to follow-up | 1 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IVDA, intravenous drug abuser.

∗ Information lacking on two patients.

† Skewed by the large number of patients who died rapidly.

TABLE 146-3 Results of Stereotactic Biopsy of HIV-Related Cerebral Lesions at George Washington University Medical Center, November 1988 to October 1990, n = 25

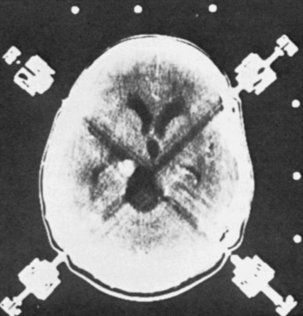

A listing of the biopsy diagnoses is also provided in Table 146-3. The relatively low incidence of toxoplasmosis, the single case of a low-grade glioma (not considered an HIV-related lesion), and the fact that five of the biopsies provided abnormal, but nondiagnostic tissue, are worth noting. Also of particular interest is that more than half of the lesions that enhanced on CT were lymphoma, and PML was the only diagnosis made from nonenhancing lesions. In fact, whether or not a lesion enhanced on CT correlated well with whether or not the biopsy affected the patient’s therapy (Table 146-4). Of the 25 target lesions, 16 enhanced with contrast, and therapy was modified in 11 of 16 on the basis of the biopsy results. Of those 11, 10 were tumors (9 lymphomas, 1 low-grade astrocytoma) and the other was an HSV infection (Fig. 146-2). These patients were either receiving anti-Toxoplasma therapy or awaiting a treatment plan at the time of their biopsy; thus, the results led to more appropriate therapy. The remaining five patients with contrast-enhancing lesions included two with incompletely treated toxoplasmosis and one with a cryptococcal abscess who had suffered recurrent cryptococcal meningitis. Appropriate treatment was confirmed in these three patients. Two (12.5%) of the 16 contrast-enhancing targets yielded abnormal, but nondiagnostic, tissue at biopsy; thus the procedure had no impact on their treatment. In short, 87.5% of the patients with contrast-enhancing lesions obtained a diagnosis from their biopsy that modified or confirmed their therapy.

TABLE 146-4 Computed Tomographic Appearance and Impact of Biopsy on Subsequent Treatment.

| Impact | Contrast Enhancing (n) | None Enhancing (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Changed treatment | 11 | 0 |

| Confirmed treatment in progress | 3 | 0 |

| No help with treatment | 2 (12.5%) | 9 (100%) |

On the other hand, the patients with nonenhancing lesions experienced no therapeutic benefit from their biopsy. The abnormal tissue was nondiagnostic in one third of these cases, and the remainder had PML, for which no effective therapy exists (see Table 146-3). Only one patient suffered a complication of the procedure when a small hemorrhage with edema occurred at the operative site, leaving him somnolent for approximately 24 hours.

Discussion

Several aspects of these data affect the surgeon’s role in HIV-related cerebral disease. First, toxoplasmosis is the cause of CNS mass lesions in 25% to 70% of cases in most large series,8,11–14 whereas it occurred in only 2 of the 25 patients reported on here (8%, see Table 146-3). This is probably a result of the approach to CNS masses in AIDS patients outlined by Rosenblum and co-workers37 and adopted by many practitioners who treat patients who have AIDS. In general, patients with contrast-enhancing lesions on CT scans are treated for at least 7 to 10 days with anti-Toxoplasma therapy as tolerated. If follow-up CT scans reveal an unsatisfactory response, or if a patient with a recent or current Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) of 70 or better deteriorates further (or fails to improve), the patient may be a candidate for biopsy. During this study, approximately 40 patients were treated at our institution for HIV-related focal cerebral lesions that were not referred for biopsy. About 20 of these had toxoplasmosis that responded to therapy, or the patients died during treatment. However, the remaining patients were treated empirically on the basis of presumptive (usually radiographic) diagnosis, or they were not treated on the basis of their clinical condition or the lack of an effective therapy (13 with presumed lymphoma and 7 with presumed PML). This result suggests a tendency on the part of the referring physicians to weigh heavily the potential for poor outcome in AIDS patients with CNS lesions against the potential benefit of having an accurate tissue diagnosis to guide appropriate therapy.

Nicolato and associates also performed stereotaxic biopsies on 25 patients with AIDS.56 Of the 25 patients, 19 came to biopsy after receiving empirical anti-Toxoplasma regimens, and the results led to a change in therapy in 90%. In addition, six patients had PML, three of whom were being treated inappropriately; however, none of these lesions enhanced on double-dose contrast CT. This reflects an experience similar to ours. However, there is no mention of patient outcome, how long the patients had suffered from AIDS before biopsy, or how many patients with contrast-enhancing lesions responded to empirical anti-Toxoplasma therapy.

Lymphoma

Outcome for AIDS-related cerebral lymphoma is poor and might justify a conservative approach toward management. In some studies, patients who did not have AIDS and who were aggressively treated for CNS lymphoma survived a median of 13.5 months, whereas AIDS patients with CNS lymphoma invariably suffered a fulminant course and died within 3 months.57,58 This effect occurs whether or not the patients are treated and whether or not their lesions respond to therapy.42 A more recent review found that HIV-positive patients with CNS lymphoma who were treated aggressively with external beam irradiation and chemotherapy survived a median of around 4 to 6 months as opposed to only 1 month if not treated.57,59 Although scant data are available to document this, many clinicians who treat large numbers of HIV-positive patients suggest that recent advances in the treatment of HIV disease might make HIV patients with CNS lymphoma more like those without HIV with regard to survival after treatment. One author has even reported on a small number of patients who survived around 3 years after aggressive treatment of their HIV-related CNS lymphoma when they also received the most effective antiviral regimen currently available.60

The data presented earlier were gathered before these recent advances. However, they suggest that patients with AIDS who develop lymphoma do so late in the course of their disease and usually die of systemic disease or of other AIDS-related diseases (all nine lymphoma patients had AIDS before their biopsy). In fact, despite accurate diagnosis and a full course of low-dose radiation therapy (20 to 30 Gy) in six of nine of the patients with lymphoma, the median survival was only 6 weeks (see Table 146-3) (the other three patients could not tolerate or refused radiation therapy or died before treatment could be completed). Moreover, all nine patients were treated for toxoplasmosis until their biopsy findings led to a change in therapy.

We have observed that patients with exceedingly low CD4 cell counts in the blood (fewer than 100 cells/μL) are more likely to have lymphoma. Conversely, those with CD4 counts above 100 cells/μL rarely have lymphoma. One set of investigators has documented an increased risk for PCNSL in HIV patients with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/μL.61 These facts raise at least two questions about AIDS patients with a contrast-enhancing lesion: Should the physician adopt an aggressive approach and should the physician treat empirically for toxoplasmosis or perform a biopsy immediately and treat accordingly? The answers might depend on the stage of the patient’s disease and his or her wishes after being informed of the prognosis and in light of his or her current and recent clinical condition.

Efficacy of Stereotactic Biopsy

Stereotactic biopsy provides an accurate diagnosis in approximately 95% of cases.56,62,63 A percentage of nondiagnostic biopsies as high as that (20%) in the series reported on earlier can be greatly improved if the appropriate techniques are employed.14,64 As mentioned, these techniques have been clearly outlined by Levy and associates.14 Immunohistochemical techniques and special stains were not routinely used in the series noted earlier, which might account for the relatively high nondiagnostic rate. However, three of the diagnoses were made by transmission electron microscopy. The small risk of not achieving a diagnosis should be considered in the decision of whether or not brain biopsy should be recommended to a patient with an AIDS-related brain lesion.

Proposed Treatment Algorithm

The role of biopsy in AIDS patients with nonenhancing brain lesions is less clear. Brain biopsy seldom contributes to the therapy in these patients, but it can provide prognostic information and may be required by future experimental treatment protocols. However, the presence of JCV DNA in the CSF of these patients may be sufficient information. Accordingly, we have implemented the algorithm in Figure 146-3 to help determine when a biopsy should be performed in AIDS patients with cerebral lesions for whom an informed decision is made to treat the lesion aggressively. It is still not clear whether or not an aggressive approach using the proposed algorithm will improve outcome in AIDS-related brain disease or decrease the number of unnecessary biopsies and increase the yield of treatable diagnoses. Real proof of improved outcome would require a randomized, controlled trial, which is not readily accomplished.

Aggressive versus Conservative Approach

Unfortunately, the question remains whether or not the risk of obtaining an accurate diagnosis is outweighed by the potential for improved survival. Accurate diagnosis, and thus appropriate therapy, can be made with absolute certainty only by obtaining tissue samples from AIDS-related brain lesions. However, patients whose lesions do not enhance on CT are apparently much less likely to have a treatable disease (they most often have PML).15 Patients with long-standing AIDS and contrast-enhancing lesions of the brain probably have lymphoma. Although most of these patients do poorly even with appropriate therapy, an earlier diagnosis and aggressive therapy in patients with a recent or current KPS of 70 or more might provide some survival benefit or, at least, useful information with regard to a treatment plan. This is especially true if current therapies for HIV disease are capable of restoring the patients’ immune systems. Moreover, patients who are recently or simultaneously found to have HIV infection cerebral lesions that enhance on CT but do not respond to anti-Toxoplasma treatment generally survive longer and thus might benefit from earlier targeted treatment for their cerebral disease. However, even under the best circumstances, survival is not likely to exceed a few months. PCR analysis of the CSF and CD4 count, and thallium-201 SPECT in some patients, might provide sufficient diagnostic data for a treatment decision.

Holloway and Mushlin undertook decision analysis to compare the treatment strategies of biopsy and no biopsy in patients with HIV disease in whom 2 weeks of anti-Toxoplasma treatment failed. They included diagnostic yield of biopsy, operative mortality, and life expectancy of lymphoma (treated and untreated). The life expectancy of the patients who had a biopsy was only 31 days greater than the 67 days predicted for those who did not have biopsies.39 Patients, referring physicians, and surgical consultants could consider this type of information when making a decision regarding diagnosis and treatment of patients with HIV-related brain lesions.

With regard to the treatment of lymphoma, there is yet another consultant whose opinion must be held in highest regard. Most radiation oncologists are reluctant, and rightly so, to irradiate the brain empirically and, therefore, insist on a tissue diagnosis before prescribing radiation therapy. However, as data such as those reported here accumulated in the early days of the treatment of HIV-related brain disease, some radiation oncologists began to empirically irradiate the brains of HIV patients who had CNS lesions that had not responded to toxoplasmosis therapy and were highly characteristic of primary cerebral lymphomas. However, when some of the data on these patients were analyzed, it appeared that the efficacy of such an approach might have been diminished by errors in diagnosis. Consequently, most radiation therapists, when currently faced with a request to treat CNS lesions in an HIV patient in whom toxoplasmosis therapy has failed, require that a tissue diagnosis be obtained before administering radiation therapy.65,66 One commentator has even expressed concerns about a catch-22 in this regard.67 He is concerned that, because in the absence of a tissue diagnosis oncologists cannot be certain that all members of a treatment group have the same diagnosis, they are thus reluctant to develop and implement aggressive treatment regimens directed at the specific diagnosis. At the same time, if the neurosurgeon is reluctant to perform a biopsy in the belief that the patient will probably suffer a poor outcome because of a lack of effective therapies, then the diagnoses required for proper treatment analyses are not available to the oncologist. This is yet another quandary in the decision-making process, and it might be solved by consultants and primary caregivers working together to develop treatment protocols and then analyzing them carefully for their efficacy.

Ethics

A certainly fatal communicable disease such as AIDS raises yet another issue in the decision-making process peculiar to such a unique circumstance, that is, whether or not the risk to the surgeon and staff should be included in the formula. Medical ethicists have addressed the issue of physicians’ obligations to treat patients with AIDS, and most feel that it is unethical for a physician to refuse to treat such patients simply because they have the disease.68,69 There are, however, certain “limiting factors,” not the least of which is “excessive risk.” As noted earlier, accurately calculating the risk of a particular surgeon’s performing a particular procedure on an AIDS patient is not feasible. Nonetheless, if the formula and data outlined by Schiff26 are applied to stereotactic biopsy, an estimated range can be derived. Assuming an injury rate of one significant injury per 50 biopsies (with a seroprevalence of 100%), 25 AIDS biopsies per year, and 30 years of practice, the probability of contracting HIV for a surgeon performing stereotactic brain biopsies on HIV-positive patients is 0.0075. By no one’s standards does this constitute excessive risk. Even this is probably an overestimate considering that inoculation during a stereotactic biopsy is extremely improbable, especially if a percutaneous technique (as opposed to a bur hole) is used. Performance of the procedure by one surgeon and one surgical technician exchanging virtually all blunt instruments (except needles for local anesthetic and a scalpel for scalp puncture) on a Mayo stand minimizes the chance of a significant injury. In addition, the procedure is practically bloodless, and the use of a bio-occlusive drape further reduces exposure.

The only other potentially acceptable limiting variable to a physician’s obligation to treat a patient with AIDS is the issue of “questionable benefit.”65 If no reasonable chance exists that the patient will benefit from the procedure, then the physician is under no obligation to treat. In fact, the physician is obliged not to treat.

Chamberlain M.C., Kormanik P.A. AIDS-related central nervous system lymphomas. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:269-276.

Chappell E.T., Guthrie B.L., Orenstein J. The role of stereotactic biopsy in the management of HIV-related focal brain lesions. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:825-829.

Holloway R.G., Mushlin A.I. Intracranial mass lesions in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: using decision analysis to determine the effectiveness of stereotactic brain biopsy. Neurology. 1996;46:1010-1015.

Kallings L.O. The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS. J Intern Med. 2008;263(3):218-243.

Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E., Rosenblum M.L. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:475-495.

Levy R.M., Russell E., Yungbluth M., et al. The efficacy of image-guided stereotactic brain biopsy in neurologically symptomatic acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:186-190.

Schiff S.J. A surgeon’s risk of AIDS. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:651-660.

Sepkowitz K.A. AIDS—the first 20 years. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1764-1772.

So Y.T., Beckstead J.H., Davis R.L. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a clinical and pathological study. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:566-572.

Vago L., Bonetto S., Nebuloni M., et al. Pathological findings in the central nervous system of AIDS patients on assumed antiretroviral therapeutic regimens: retrospective study of 1597 autopsies. AIDS. 2002;16(14):1925-1928.

Weiss R.A. How does HIV cause AIDS? Science. 1993;260(5112):1273-1279.

1. Sepkowitz K.A. AIDS—the first 20 years. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1764-1772.

2. Weiss R.A. How does HIV cause AIDS? Science. 1993;260(5112):1273-1279.

3. Gottlieb M.S. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles, 1981. Am J Public Health. 2006;9(6):980-981. discussion 982–3

4. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Update on acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31(37):507-508. 513–514

5. Kallings L.O. The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS. J Intern Med. 2008;263(3):218-243.

6. . Worldwide AIDS & HIV Statistics. AVERT, 2009 http://www.avert.org/worldstats.htm

7. Vago L., Bonetto S., Nebuloni M., et al. Pathological findings in the central nervous system of AIDS patients on assumed antiretroviral therapeutic regimens: retrospective study of 1597 autopsies. AIDS. 2002;16(14):1925-1928.

8. So Y.T., Beckstead J.H., Davis R.L. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a clinical and pathological study. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:566-572.

9. De Girlami U., Smith T.W., Hienin D., Hauw J.J. Neuropathology of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:643-655.

10. Kanzer M.D. Neuropathology of AIDS. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1990;5:313-362.

11. Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E., Rosenblum M.L. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:475-495.

12. Loneragan R., Doust B.D., Walker J. Neuroradiological manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Australas Radiol. 1990;34:32-39.

13. Masliah E., DeTeresa R.M., Mallory M.E., Hansen L.A. Changes in pathological findings at autopsy in AIDS cases for the last 15 years. AIDS. 2000;14(1):69-74.

14. Levy R.M., Russell E., Yungbluth M., et al. The efficacy of image-guided stereotactic brain biopsy in neurologically symptomatic acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:186-190.

15. Chappell E.T., Guthrie B.L., Orenstein J. The role of stereotactic biopsy in the management of HIV-related focal brain lesions. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:825-829.

16. Corti M., Metta H., Villafañe M.F., et al. Stereotactic brain biopsy in the diagnosis of focal brain lesions in AIDS. Medicina (B Aires). 2008;68(4):285-290.

17. Vallat-Decouvelaere A.V., Chrétien F., Lorin de la Grandmaison G., et al. The neuropathology of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Pathol. 2003;23(5):408-423.

18. Apuzzo M.J., Chandrasoma P.T., Cohen D., et al. Computed imaging stereotaxy: experience and perspective related to 500 procedures applied to brain masses. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:930-937.

19. Falloon J. Current therapy for HIV infection and its complications. Postgrad Med. 1992;91:115-132.

20. Broder S.(moderator). Antiretroviral therapy in AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:604-618.

21. Kuo J.M., Taylor J.M., Detels R. Estimating the AIDS incubation period from a prevalent cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:1050-1057.

22. Salzberg A.M., Dolins S.L., Salzberg C. HIV incubation times. Comment on Lancet. 1989;1(8645):1026-1027. Lancet 2(8655):66, 1989

23. Kolson D.L. Neuropathogenesis of central nervous system HIV-1 infection. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:703-717.

24. Lambotte O., Deiva K., Tardieu M. HIV-1 persistence, viral reservoir, and the central nervous system in the HAART era. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:95-103.

25. Roullet E. Opportunistic infections of the central nervous system during HIV-1 infection (emphasis on cytomegalovirus disease). J Neurol. 1999;246:237-243.

26. Schiff S.J. A surgeon’s risk of AIDS. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:651-660.

27. Lowenfels A.B., Wormser G.P., Jain R. Frequency of puncture injuries in surgeons and estimated risk of HIV infection. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1284-1286.

28. Del Valle L., Piña-Oviedo S. HIV disorders of the brain: pathology and pathogenesis. Front Biosci. 2006;11:718-732.

29. Dina T. Primary central nervous system lymphoma versus toxoplasmosis in AIDS. Radiology. 1991;179:823-828.

30. Thurnher M.M., Rieger A., Kleibl-Popov C., et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in AIDS: a wider spectrum of CT and MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 2001;43:29-35.

31. O’Malley J.P., Ziessman H.A., Kumar P.N., et al. Diagnosis of intracranial lymphoma in patients with AIDS: value of SPECT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:417-421.

32. Giancola M.L., Rizzi E.B., Schiavo R., et al. Reduced value of thallium-201 single-photon emission computed tomography in the management of HIV-related focal brain lesions in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20(6):584-588.

33. Rodriguez W.L., Ramirez-Ronda C.H. CNS involvement in AIDS patients as seen with CT and MR: a review. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1991;83:548-551.

34. Skiest D.J., Erdman W., Chang W.E., et al. SPECT thallium-201 combined with Toxoplasma serology for the presumptive diagnosis of focal central nervous system mass lesions in patients with AIDS. J Infect. 2000;40:274-281.

35. Kupfer M.C., Chi-Shing Z., Colletti P.M., et al. MRI evaluation of AIDS-related encephalopathy: toxoplasmosis vs. lymphoma. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:51-56.

36. Mariuz P.R., Luft B.J. Toxoplasmic encephalitis. AIDS Clin Rev. 1992;1:105-130.

37. Pons V.G., Jacobs R.A., Hollander H., et al. Nonviral infections of the central nervous system in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In: Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E. AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press; 1988:263-284.

38. Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E. Algorithms for the treatment of AIDS patients with neurologic disease. In: Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bresdesen E. AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press; 1988:389-396.

39. Holloway R.G., Mushlin A.I. Intracranial mass lesions in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: using decision analysis to determine the effectiveness of stereotactic brain biopsy. Neurology. 1996;46:1010-1015.

40. Remick S.C., Diamond C., Migliozzi J.A., et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in patients with and without the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69:345-360.

41. So Y.T., Chaoucoir A., Davis R.L., et al. Neoplasms of the central nervous system in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In: Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E. AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press; 1988:285-300.

42. Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bresdesen D.E. AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press, 1988.

43. Cinque P., Brytting M., Vago L., et al. Epstein-Barr virus DNA in CSF from patients with AIDS-related primary lymphoma of the CNS. Lancet. 1993;342:398-401.

44. MacMahon E., Glass J.D., Hayward S.F., et al. Epstein-Barr virus: a tumor marker for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Blood. 1991;78S:399.

45. Cinque P., Bossolasco S., Bestetti A., et al. Molecular studies of cerebrospinal fluid in human immunodeficiency virus type 1–associated opportunistic central nervous system diseases—an update. J Neurovirol. 2002;8(suppl 2):122-128.

46. Tachikawa N., Goto M., Hoshino Y., et al. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii, Epstein-Barr virus, and JC virus DNAs in the cerebrospinal fluid in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients with focal central nervous system complications. Intern Med. 1999;38:556-562.

47. Antinori A., Cingolani A., De Luca A., et al. Epstein-Barr virus in monitoring the response to therapy of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:259-261.

48. Lazzarin A., Castagna A., Cavalli G., et al. Cerebrospinal fluid beta 2-microglobulin in AIDS related central nervous system involvement. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1992;38:175-186.

49. Antinori A., Ammassari A., De Luca A., et al. Diagnosis of AIDS-related focal brain lesions: a decision-making analysis based on clinical and neuroradiologic characteristics combined with polymerase chain reaction assays in CSF. Neurology. 1997;48:687-694.

50. d’Arminio Monforte A., Cinque P., Vago L., et al. A comparison of brain biopsy and CSF-PCR in the diagnosis of CNS lesions in AIDS patients. J Neurol. 1997;244:35-39.

51. Kurisaki H. Central nervous system tuberculosis with and without HIV infection—clinical, neuroimaging, and neuropathological study [in Japanese]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2000;40:209-217.

52. Cingolani A., De Luca A., Larocca L.M., et al. Minimally invasive diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–related primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:364-369.

53. Portolani M., Cermelli C., Meacci M., et al. Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and central nervous system disorders. New Microbiol. 1999;22:369-374.

54. De La Paz R., Enzmann D. Neuroradiology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. In: Rosenblum M.L., Levy R.M., Bredesen E. AIDS and the Nervous System. New York: Raven Press; 1988:121-154.

55. Rauch R.A., Bazan C.III, Jinkins J.R. Imaging of infections of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Radiol. 1992;4:43-51.

56. Nicolato A., Gerosa M., Piovan E., et al. Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance guided stereotactic brain biopsy in nonimmunocompromised and AIDS patients. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:267-277.

57. Baumgartner J.E., Rachlin J.R., Beckstead J.H., et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas: natural history and response to radiation therapy in 55 patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:206-211.

58. Hochberg F.H., Miller D.C. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:835-853.

59. Chamberlain M.C., Kormanik P.A. AIDS-related central nervous system lymphomas. J Neurooncol. 1999;43:269-276.

60. Hoffman C., Tabrizian S., Wolf E., et al. Survival of AIDS patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma is dramatically improved by HAART-induced immune recovery. AIDS. 2001;15:2119-2127.

61. Pluda J.M., Venzon D.J., Tosato G., et al. Parameters affecting the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in patients with severe human immunodeficiency virus infection receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1099-1107.

62. Friedman W.A., Sceats D.J., Blake R.N., Ballinger W.E. The incidence of unexpected pathological findings in an image-guided biopsy series: a review of 100 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:180-184.

63. Kaufman H.K., Catalano L.W. Diagnostic brain biopsy: a series of 50 cases and a review. Neurosurgery. 1979;4:129-136.

64. Zimmer C., Daeschlein G., Patt S., Weigel K. Strategy for diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii in stereotactic brain biopsies. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1991;56:66-75.

65. So Y.T., Beckstead J.H., Davis R.L. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome: a clinical and pathological study. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:566-572.

66. Donahue B.R., Sullian J.W., Cooper J.S. Additional experience with empiric radiotherapy for presumed human immunodeficiency virus–associated primary CNS lymphoma. Cancer. 1995;75:328-332.

67. Corn B.W., Trock J.T., Curran W.J.Jr. Management of primary central nervous system lymphoma for the patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: confronting a clinical catch-22. Cancer. 1995;76:163-166.

68. Emanuel E.J. Do physicians have an obligation to treat patients with AIDS? N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1686-1690.

69. Zuger A., Miles S.H. Physicians, AIDS, and occupational risk. JAMA. 1987;258:1924.