Chapter 15 Neurosurgical emergencies

This chapter covers the approach to the patient who presents with headache as well as the following topics:

GENERAL CONCEPTS

Primary versus secondary brain injury

Normally ICP is between 5 and 10 mmHg. Autoregulatory mechanisms will maintain constant cerebral blood flow when the cerebral perfusion varies between 50 and 150 mmHg. In some patients, such as those with severe head injury, cerebral autoregulation may be lost. Any process that reduces MAP (e.g. hypovolaemic shock) or increases ICP (post-injury oedema, expanding intracranial haematoma or mass, hypercarbia) will compromise cerebral perfusion, leading to secondary brain injury.

Headache

Boxes 15.1 and 15.2 outline some criteria for computerised tomography (CT) scanning of both trauma and non-trauma patients, respectively. Further information regarding the features of different types of headaches is given under the heading of each specific diagnosis.

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

The GCS is a widely accepted scale for assessing alterations to a patient’s level of consciousness. A score is given based on 3 components—eye opening, verbal response and motor response (see Table 15.1). In adults, the score achieved correlates well with the severity of the underlying condition. It is also useful for objectively following a patient’s progress. Maximum score is 15 and minimum is 3.

| Eye opening | Spontaneous | 4 |

| To voice | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Best verbal response | Alert | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words only | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| Nil | 1 | |

| Best motor response | Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localises pain | 5 | |

| Withdraws to pain | 4 | |

| Abnormal flexion | 3 | |

| Abnormal extension | 2 | |

| None | 1 |

Herniation syndromes

The cranial cavity is divided into compartments by sheets of dura mater (the falx cerebri and tentorium cerebelli). The tentorium separates the cerebrum above from the cerebellum and brainstem below. Because of the rigidity and non-expansile nature of the cranial vault, significant increases in ICP can lead to herniation syndromes where the contents of one compartment herniate across an opening in these dural structures, causing specific neurological signs. The significance of a herniation syndrome is that ICP has increased beyond the capacity of the brain to compensate and death will ensue if emergent treatment is not undertaken. Raised ICP above the tentorium leads to herniation of the uncus of the temporal lobe. This manifests as dilation of ipsilateral pupil (later bilateral), contralateral pyramidal weakness and increased tone.

Raised ICP will also lead to high blood pressure and bradycardia (Cushing response).

Management principles

Airway, breathing and circulation

A patent airway is the first priority (see Chapter 2, ‘Securing the airway, ventilation and procedural sedation’). Simple manoeuvres to maintain patency may prevent secondary brain injury from hypoxia. Airway protection is also important—patients with a GCS of 8 or less will not be able to protect their airway from aspiration or maintain a patent airway and need intubation. Adequate ventilation is required to avoid hypoxia and hypercarbia. Treatment measures vary from oxygen therapy by mask to full mechanical ventilation if required. Adequate CPP relies in part on a normal blood pressure. Hypotension should therefore be treated with volume expansion.

Measures to decrease ICP

A number of interventions can reduce ICP.

Hyperventilation to lower than normal PCO2 is not recommended, as this causes cerebral vasoconstriction and does not improve outcome. In ventilated patients, target PCO2 should be in the normal range.

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY (TBI)

Classification and pathophysiology

There are different ways of classifying TBI. Each is useful in that there is some relationship to treatment and prognosis. Table 15.2 outlines a classification according to actual pathology of the injury. TBI can be classified according to severity based on GCS (GCS ≤ 8 = severe, GCS 9–13 = moderate, and GCS 14–15 = mild or minor).

Table 15.2 Pathological lesions seen in traumatic brain injury

| Type of injury | Lesion |

|---|---|

| Skull fractures | Depressed |

| Base of skull | |

| Linear | |

| Cerebral contusion | |

| Haemorrhage | Intracerebral |

| Subarachnoid | |

| Subdural | |

| Extradural | |

| Diffuse axonal injury |

Assessment and diagnosis

Assessment should be performed according to advanced trauma life support principles, which use a prioritised and systematised approach (for general principles of trauma management, see Chapter 14, ‘Initial assessment and management of major trauma’). The diagnosis of TBI per se is usually obvious from the history. However, the occasional patient presents with an altered conscious state without a definite history of trauma. In cases where the patient may have been drinking alcohol, it is sometimes misdiagnosed as alcohol or drug intoxication. This is a classic misdiagnosis that can have lethal consequences.

Clinical features

The severity of mechanism of injury, a history of loss of consciousness and the duration of loss of consciousness are important. Did the patient regain consciousness? The patient may be experiencing symptoms such as headache, nausea and vomiting. There may be amnesia concerning the events around the time of injury, or for a period before the injury (retrograde amnesia). Anterograde amnesia is the inability to remember information acquired since the injury. This often manifests as the patient asking the same questions over and over again. On examination, local head trauma (lacerations, haematomas) may be present. The GCS should be measured (Table 15.1). Focal neurological signs such as pupillary dilatation with or without hemiparesis with increased tone and reflexes indicate an uncal herniation syndrome requiring emergent management. Where there is significant increase in ICP, the Cushing reflex will lead to hypertension and bradycardia. Clues to a fractured skull base are cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak from nose, bilateral periorbital bruising (raccoon eyes), CSF leak from the ear, haemotympanum and bruising behind the ear (Battles sign).

Investigations

Definitive investigation is a CT scan of the head. This should be done urgently for severe and moderate head injuries. For mild head injury (GCS 14–15), the indications are listed in Box 15.1.

Management

Measures to reduce ICP

The specific measures mentioned above are appropriate for all patients with severe TBI. Mannitol (5 mL of 20% solution/kg body weight) is usually reserved for those who have evidence of a herniation syndrome, evidence of mass effect on CT, or high ICP as measured on an ICP monitor.

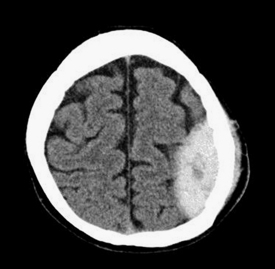

Surgical intervention

Surgery is required for drainage of extradural (see Figure 15.1) and subdural haematomas. This may be required emergently if they are causing mass effect with raised intracranial pressure. Supportive therapy is required for contusions, subarachnoid haemorrhage and diffuse axonal injury. Surgery is also required for depressed skull fracture. In severe head injuries, insertion of an intracranial pressure monitor and monitoring of intra-arterial blood pressure to direct therapy (see above) is aimed at reducing raised ICP. To maintain adequate cerebral blood flow, a CPP of above 70 is ideal.

Other acute treatments

Patients with mild head injury not having a CT scan should be observed until they have been normal and symptom-free for an appropriate length of time. In most emergency departments, 4 hours is the period used. When discharged, these patients should be provided with written head injury advice.

NON-TRAUMATIC INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGES

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

(See also Chapter 24, ‘Neurological emergencies’.)

Clinical features

There are different scoring systems available for grading the severity of SAH, all of which do a reasonable job in predicting mortality, functional outcome for survivors and length of hospital stay. Table 15.3 outlines the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grading system for subarachnoid haemorrhage and its relation to mortality.

Table 15.3 The World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grading system for subarachnoid haemorrhage

| Grade | GCS and motor deficit | Mortality2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | GCS 15 | 5 |

| II | GCS 13–14, no motor deficit | 9 |

| III | GCS 13–14, with motor deficit | 20 |

| IV | GCS 7–12 | 33 |

| V | GCS 3–6 | 77 |

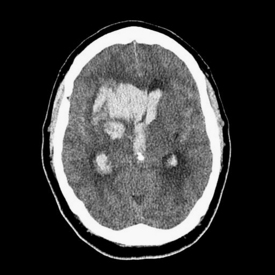

Investigations

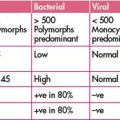

Diagnosis of the bleed is usually by cerebral CT scan (see Figure 15.2). The ability of a cerebral CT to pick up a SAH degrades over time. If scanned with a third-generation CT scanner within the first 24 hours, 98% will be visible;3 however, by 1 week post-bleed only 50% are visible.

The LP should be examined for the presence of blood (either macroscopic or microscopic). If red blood cells are present, it is difficult to differentiate a traumatic tap from a subarachnoid haemorrhage. The CSF should be examined for breakdown products of red blood cells (oxyhaemoglobin and bilirubin) by CSF spectrophotometry. Oxyhaemoglobin takes 2 or more hours to develop, but bilirubin takes 12 hours to develop. A traumatic tap can give rise to oxyhaemoglobin only, but the presence of both bilirubin and oxyhaemoglobin peaks on spectrophotometry is suggestive of SAH.

Once a SAH is detected, further imaging is required to demonstrate the source of the bleed. This is done with either 4-vessel cerebral angiography or CT angiogram (Circle of Willis). The latter is a less invasive alternative that can identify aneurysms and AV malformations. It has a sensitivity of approximately 96% for aneurysms greater than 3 mm diameter.3 It has not replaced conventional cerebral angiography but is useful in investigating patients with high clinical suspicion of SAH but who have equivocal or negative CT and LP.

Treatment

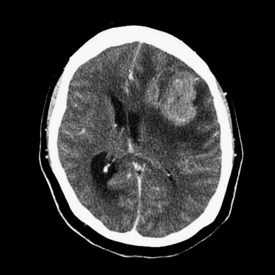

Spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage

Patients usually present with sudden onset headache and neurological impairment. Focal neurological signs are usually related to the location of the bleed. In larger bleeds (see Figure 15.3), especially where there is mass effect, there is usually reduced level of consciousness or coma. Herniation syndromes may be seen, especially with posterior intracranial fossa bleeds.

Subdural haematoma

Clinical features

Depending on the time course of the bleed, a subdural haematoma can be acute, subacute or chronic. When large, it presents with symptoms of mass effect (see ‘Emergency presentations of space-occupying lesions’ below). Other symptoms include headache, confusion and ataxia.

EMERGENCY PRESENTATIONS OF SPACE-OCCUPYING LESIONS

Clinical features

The clinical presentation is by virtue of the enlarging size of the lesion, mass effect (local or general) or surrounding oedema (see Figure 15.4). Symptoms vary greatly from just headaches, with features suggestive of raised ICP, to patients with coma and herniation syndromes at the severe end of the spectrum.

COMPLICATIONS OF VENTRICULAR DRAINAGE DEVICES

VERTEBRAL COLUMN AND SPINAL CORD INJURIES

Vertebral column injury refers to injury of any of the bones, joints and ligaments that make up the vertebral column. This may or may not be associated with spinal cord injury, which refers to injury of the spinal cord itself and is associated with neurological deficit.

Clinical features

Assessment of presence of spinal cord injury

Other clinical clues that suggest spinal cord injury are diaphragmatic breathing in high-mid to lower cervical spine injury (loss of intercostal power supplied by thoracic cord with intact diaphragm supplied by C4, C5 and C6). In males, priapism may be present due to loss of sympathetic tone. There may also be hypotension and bradycardia due to loss of sympathetic vascular tone. Other causes of shock from trauma (haemorrhage, pericardial tamponade and tension pneumothorax) must be ruled out.

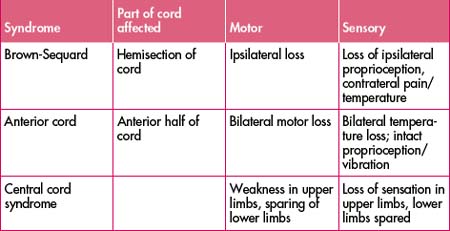

Whether or not the cord lesion is complete or partial is obviously vital for prognosis. Complete lesions have total loss of all three modalities (motor, sensory and autonomic). Partial lesions can have some residual function in any of the modalities. There are some syndromes with typical patterns of deficit indicating injury to certain parts of the cord (Table 15.4).

Investigations

In patients who cannot be cleared clinically, radiological assessment should be done.

Other films may be useful in certain situations. Oblique views of the cervical spine can be used to evaluate the facet joints on each side. They can also be used as an alternative to swimmer’s view in imaging the cervicothoracic junction. Flexion and extension views are indicated to detect instability in an otherwise normal cervical spine with symptoms. Recent literature has questioned the value of flexion and extension views in detecting injuries not already seen on plain films.

Accurate interpretation of plain cervical spine films can be difficult and less experienced doctors should check their interpretation with an emergency physician. Box 15.3 outlines a system for reviewing cervical spine X-rays. Abnormalities may be non-specific and simply draw attention to the need for further imaging. (See also the ‘plain X-ray views’ section under ‘Trauma’ in ‘Emergencies in the neck’ in Chapter 4, ‘Diagnostic imaging in emergency patients’)

Box 15.3 Checklist for assessment of cervical spine X-rays

Indications for computerised tomography (CT)

CT is indicated in the following circumstances:

Treatment

In the patient with multiple injuries, vertebral column and spinal cord injuries should be managed as part of a prioritised management plan that addresses other serious injuries in context (see Chapter 14 for general principles of trauma management). The consequences of injury to the spinal cord in a patient with an unstable vertebral column injury are of major life-changing significance for the patient. Precautions to prevent further injury to the cord should therefore be instituted from the beginning.

Immobilisation of vertebral column

Numerous orthoses are available to minimise vertebral column movements. There is no perfect splint that prevents all vertebral column movements, particularly in uncooperative patients. Cervical collars restrict but do not completely prevent cervical spine movement. Soft collars are very poor at preventing movement; hard collars are better. At a minimum, any patient with a suspected cervical spine fracture should wear a hard cervical collar and the techniques for transfer outlined above should be used. Additional immobilisation with ‘sandbags’ may be used. Imaging should be expedited, as prolonged periods in hard collars and lying supine without moving are uncomfortable and painful.

High-dose corticosteroids

The use of early high-dose methylprednisolone is controversial. Evidence of a benefit is limited to one large, prospective placebo-controlled randomised study4 in which patients with cervical spine injury were treated with 24 hours of methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg bolus followed by 5.4 mg/kg/hour infusion). This failed to show any improvement in morbidity or mortality, but those treated within 8 hours showed a greater improvement in return of motor ability (5 points) and sensation (2–3 points) as measured on a 70-point scale at 6 weeks and 6 months.

The validity of this study has been questioned because of the methods of statistical analysis employed, the functional significance of the measured motor and sensory improvements is unclear, and the results have not been confirmed in other trials.5 The potential benefit must then be weighed up against the adverse risks of high-dose methylprednisolone.

1 Stiell I.G., et al. The Canadian head CT rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001;357:1391-1396.

2 Oshiro E., Walter K.A., Piantadosi S., et al. A new subarachnoid hemorrhage grading system based on Glasgow Coma Scale: a comparison with the Hunt and Hess and World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scales in a clinical series. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(1):140-148.

3 Al-Shahi R., White P.M., Davenport R.J., Lindsay K.W. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. BMJ. 2006;333:235-240.

4 Bracken M.B., et al. A randomized controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1405.

5 Pointillart V., et al. Pharmacological therapy of spinal cord injury during the acute phase. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:71.