CHAPTER 96 NEUROSARCOIDOSIS AND NEURO-BEHÇET’S DISEASE

NEUROSARCOIDOSIS

Neurosarcoidosis is a localized manifestation of sarcoidosis involving the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system (PNS). Sarcoidosis, a multisystemic granulomatous inflammatory disorder of unknown cause, is manifested frequently as a pulmonary and lymph node disease that typically appears in young adults between 20 and 40 years of age. Neurosarcoidosis may occur in 5% to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis as part of multiorgan disease involvement or as the first localized manifestation of the disease.1 The pathological hallmark of sarcoidosis is the presence of noncaseating granulomatous tissue reactions and of inflammation dominated by macrophage activation, as well as mononuclear and lymphocytic infiltration. In the nervous system, noncaseating granulomas and inflammation may occur in any compartment of the CNS or PNS, producing focal or multifocal tissue damage that leads to neurological dysfunction.

Epidemiology and Etiopathogenesis

The prevalence of sarcoidosis varies among different populations worldwide. In the United States, it appears to be more common in African Americans and white persons of northern European descent. In addition, foci of increased frequency of sarcoidosis have been described in some European countries. In developing countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, the prevalence of sarcoidosis remains uncertain because the high incidence of infectious granulomatous disorders such as tuberculosis, which closely resembles sarcoidosis, predominates as a clinical diagnosis. A multicenter case-control study of etiological factors in 736 patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis in the United States1 revealed neurological involvement in 4.6% of the patients. Interestingly, this study also revealed that women were more likely than men to have neurosarcoidosis and ocular involvement of the disease. The factors causing neurological involvement are still unknown, and it is still unclear whether racial or genetic factors play a role in determining the presence of CNS or PNS involvement.

The etiological factors involved in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis remain elusive, but several hypotheses have suggested a potential role of infection, exposure to environmental factors, and noninfectious factors. The occurrence of geographical clusters and the increased risk among first- and second-degree relatives of patients with sarcoidosis are indicative of a role for an environmental or infectious etiological factor.2 Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Propionibacterium acnes, and Propionibacterium granulosum infections have emerged as potential agents in polymerase chain reaction studies of tissue biopsy specimens from patients with sarcoidosis; however, definitive studies to demonstrate a definite role for these or other infective agents have not been carried out.3 Genetic susceptibility, as determined by varying effects of several genes, has been proposed as an important factor determining the presence and variability of the clinical profile of sarcoidosis in different ethnic populations.4 Some major histocompatibility complex (MHC) alleles have been found to confer susceptibility to sarcoidosis (human leukocyte antigen [HLA]–DR11, -DR12, -DR14, -DR15, and -DR17) whereas others appear to be protective (HLA-DR1, HLA-DR4, and possibly HLA-DQ*0202). Polymorphisms in the angiotensin-converting enzyme, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and vascular endothelial growth factor genes have also been postulated to be associated with the disease in some population-based studies.5,6

Clinical Features

The clinical manifestations of neurosarcoidosis are heterogeneous, as noncaseating granulomas and inflammation may affect any compartment of the CNS and PNS (Table 96-1). The most frequent manifestations of neurosarcoidosis are associated with cranial neuropathy and the meningeal and encephalitic forms of the disease; clinical manifestations may overlap and produce complex neurological symptoms. The clinical course of neurosarcoidosis is variable and may exhibit a temporal profile consistent with a monophasic, relapsing-remitting, or chronic pattern. The extent of the CNS or PNS involvement and the evolution of clinical problems determine the magnitude of the patient’s neurological disability. Some of the acute manifestations of neurosarcoidosis, such as cranial neuropathies, have a monophasic pattern that resolve quickly with steroid treatment; others, such as the meningeal, encephalitic, and myelopathic forms, frequently have a subacute course that may evolve into relapsing-remitting or chronic forms of the disease, necessitating more aggressive treatment approaches.

| Clinical Forms | Neurological Manifestation | Clinical Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Meningeal form | Aseptic meningitis | Headaches |

| Basal meningitis | Increase intracranial pressure | |

| Chronic meningitis | Hydrocephalus | |

| Pachymeningitis | Single or multiple cranial nerve palsies | |

| Dural tumor-like sarcoid lesions | ||

| Cranial neuropathy form | Facial paralysis | Single or multiple cranial nerve palsies |

| Optic neuropathy | Bilateral Bell’s palsy | |

| Multiple cranial neuropathies | Diplopia | |

| Visual blurriness | ||

| Vestibular symptoms | ||

| Encephalitic form | Focal encephalitis | Headaches |

| Focal or multifocal leukoencephalitis | Psychosis | |

| Tumor-like sarcoid lesions | Seizures | |

| Focal neurological symptoms | ||

| Increased intracranial pressure | ||

| Neuroendocrine form | Panhypopituitarism | Diabetes insipidus |

| Hypogonadism | ||

| Hypothyroidism | ||

| Myelopathic form | Subacute or progressive myelopathy | Gait disturbances |

| Paraparesis/paraplegia | ||

| Bladder dysfunction | ||

| Paresthesias/dysesthesias | ||

| Sensory level disturbances | ||

| Neuropathic form | Multiple mononeuropathies | Multifocal or localized dysesthesias, paresthesias, weakness, monoradiculoneuropathies or polyradiculoneuropathies |

| Polyradiculoneuropathies | ||

| Myopathic form | Focal myositis | Weakness, muscle pain |

| Polymyositis |

Meningeal Forms

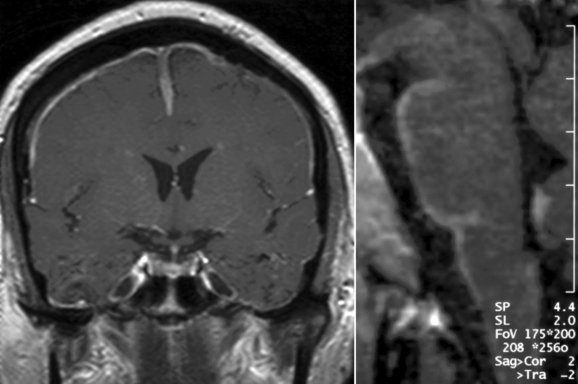

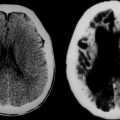

Basal meningitis, chronic meningitis, and pachymeningitis are frequent manifestations among the meningeal forms of neurosarcoidosis (Fig. 96-1). A careful clinical assessment and contrast-enhanced magnetic brain imaging (MRI) studies, as well as a complete examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), are necessary to rule out the presence of other diseases that frequently involve the basal meningeal compartment, including tuberculous and fungal or neoplastic meningitis. Because the basal region of the brain is one of the areas most commonly affected by meningeal forms, cranial nerve palsies and hydrocephalus are the most frequent clinical manifestations of these forms of neurosarcoidosis. In patients with meningeal forms of neurosarcoidosis, granulomatous inflammatory reactions may impair the reabsortion of the CSF in the arachnoid villi and/or produce obstruction of CSF outflow. This accumulation of fluid leads to aggressive forms of hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure. Special precautions should be taken in patients with hydrocephalus associated with neurosarcoidosis, because lumbar puncture procedures may increase the risk of decompensation and cerebellar tonsillar herniation. Some of these patients may require ventriculostomy or ventriculoperitoneal shunts to avoid further complications from increased intracranial pressure, but the decision to use these neurosurgical approaches must be made carefully. Other variants of meningeal involvement in neurosarcoidosis include spinal arachnoiditis or dural tumor-like lesions that resemble meningiomas and produce focal symptoms in the intracranial or spinal compartments, with increased intracranial pressure or myelopathic symptoms, respectively. These tumor-like lesions are associated with extensive but localized noncaseating granulomatous and inflammatory reactions of the dura mater and respond well to medical treatment without the need for surgical resection, except in situations in which there is a marked mass effect or increased intracranial pressure.

Encephalitic Forms

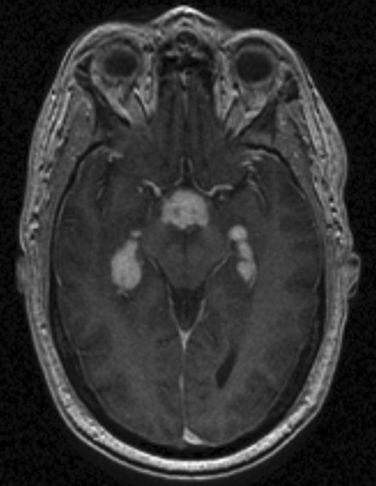

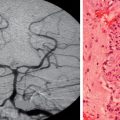

Focal encephalitis, leukoencephalitis, and multifocal white matter involvement are aggressive forms of neurosarcoidosis, inasmuch as these manifestations are frequently associated with subacute, relapsing-remitting or chronic patterns (Fig. 96-2). Symptoms associated with encephalitic forms include seizures, headache, signs of increased intracranial pressure, psychosis, motor dysfunction, cognitive decline, and other focal neurological manifestations. Focal or multifocal leukoencephalitic forms of neurosarcoidosis may mimic the clinical and MRI features of multiple sclerosis and/or neoplastic lesions. Patients with suspected demyelinating diseases should be evaluated to rule out the presence of sarcoidosis before the definitive diagnosis of such disorders is established. Some of the focal encephalitic forms of neurosarcoidosis represent aggressive forms of parenchymal CNS disease that become refractory to conventional treatment with steroids and may necessitate aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.

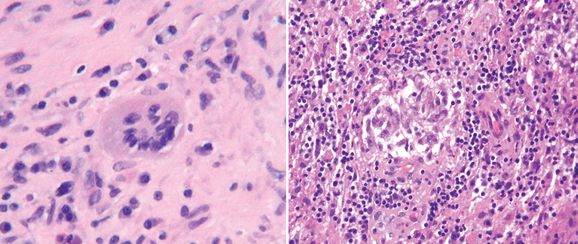

Figure 96-2 T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) with gadolinium enhancement in a patient with an encephalitic form of neurosarcoidosis. The brain MRI changes raised concerns for a glioblastoma multiform, but a brain biopsy revealed typical features of granulomatous reactions and multinucleated giant cell formation (see Fig. 96-5).

Neuroendocrine Forms

Some patients with neurosarcoidosis exhibit a selective focal granulomatous meningeal inflammation of the infundibular, peri-infundibular, and suprasellar regions that may evolve into aggressive forms of hypothalamic dysfunction, focal encephalitis, and/or hypophysitis (Fig. 96-3). These localized manifestations of neurosarcoidosis manifest clinically with a variety of hormonal deficiencies but frequently with hypogonadism, central diabetes insipidus, and panhypopituitarism. In patients with this form of neuroendocrine involvement, the granulomatous inflammatory activity is often monophasic and subacute but produces important long-standing endocrine problems that necessitate life-long hormonal replacement and careful endocrinological follow-up.

Myelopathic Forms

Although not as common as other forms of neurosarcoidosis, myelopathic forms may represent a diagnostic challenge if there is no previous history of systemic sarcoidosis. Myelopathic forms are frequently manifested as subacute or slowly progressive myelopathies associated with both motor and sensory symptoms. A presumptive or possible diagnosis of sarcoid myelopathy may be established if the patient has a previous history of systemic sarcoidosis, clinical evidence of myelopathy documented by clinical findings, and MRI findings of focal or multifocal intra-axial spinal cord lesions (Fig. 96-4). Because involvement of the spinal cord is frequently associated with slowly progressing tumor-like lesions, the diagnosis of sarcoid myelopathy is occasionally established after spinal cord biopsies are performed in patients with suspected spinal cord tumors.

Diagnostic Approaches

Clinical investigation of patients with suspected neurosarcoidosis requires a careful assessment of the systemic manifestations of the disease along with neurological evaluation. In the majority of patients with clinical manifestations of neurosarcoidosis, evidence of systemic disease is already established. However, in almost 50% of patients with suspected neurosarcoidosis, the neurological symptoms represent the first defining manifestation of sarcoidosis. In these patients, a more extensive and careful assessment of systemic involvement is necessary to establish a diagnosis of definite or probable neurosarcoidosis. Three categories have been established in the diagnostic assessment of neurological involvement in sarcoidosis:7

A diagnosis of definite neurosarcoidosis may be established in patients with symptoms consistent with any of the neurological forms of sarcoidosis and with pathological documentation of granulomatous inflammation obtained from CNS or PNS tissue biopsy.

A diagnosis of definite neurosarcoidosis may be established in patients with symptoms consistent with any of the neurological forms of sarcoidosis and with pathological documentation of granulomatous inflammation obtained from CNS or PNS tissue biopsy. A diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis may be established if the clinical profile is consistent with any of the neurological forms of the disease and is supported by CSF or imaging studies, proof of sarcoidosis in nonneural tissue biopsy, and ruling out of other potential causes of neurological dysfunction.

A diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis may be established if the clinical profile is consistent with any of the neurological forms of the disease and is supported by CSF or imaging studies, proof of sarcoidosis in nonneural tissue biopsy, and ruling out of other potential causes of neurological dysfunction. A diagnosis of possible neurosarcoidosis may be established if the clinical profile is consistent with any of the forms of neurosarcoidosis and if other possible causes of neurological dysfunction are ruled out.

A diagnosis of possible neurosarcoidosis may be established if the clinical profile is consistent with any of the forms of neurosarcoidosis and if other possible causes of neurological dysfunction are ruled out.Assessment of Neurological Involvement in Sarcoidosis

MRI of the brain or spinal cord is a necessary step in evaluating the magnitude and extent of the disease. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI studies are very helpful in establishing the patterns and topography of leptomeningeal or dural enhancement in meningeal forms and in facilitating the evaluation of the magnitude of active inflammation in encephalitic and myelopathic forms of the disease.

MRI of the brain or spinal cord is a necessary step in evaluating the magnitude and extent of the disease. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI studies are very helpful in establishing the patterns and topography of leptomeningeal or dural enhancement in meningeal forms and in facilitating the evaluation of the magnitude of active inflammation in encephalitic and myelopathic forms of the disease. CSF analysis is necessary to investigate and rule out other potential etiologies, such as tuberculous, fungal or neoplastic meningitis, and other neurological disorders, and to determine the magnitude of the inflammatory activity. Mononuclear pleocytosis, an elevated protein concentration, an increased immunoglobulin G index, and the presence of oligoclonal bands are useful parameters in the evaluation of inflammatory activity. Unfortunately, the assessment of angiotensin-converting enzyme in CSF is rarely useful, because this test lacks sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of patients with neurosarcoidosis.

CSF analysis is necessary to investigate and rule out other potential etiologies, such as tuberculous, fungal or neoplastic meningitis, and other neurological disorders, and to determine the magnitude of the inflammatory activity. Mononuclear pleocytosis, an elevated protein concentration, an increased immunoglobulin G index, and the presence of oligoclonal bands are useful parameters in the evaluation of inflammatory activity. Unfortunately, the assessment of angiotensin-converting enzyme in CSF is rarely useful, because this test lacks sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of patients with neurosarcoidosis. CNS or PNS tissue biopsy is helpful in establishing a definitive diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. However, as for all invasive brain procedures, the decision to obtain meningeal, brain, or spinal cord tissue biopsy specimens should be based on the need to establish a pathological diagnosis essential for treatment in the absence of other clinical or pathological data that support the diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis. In the majority of cases, a diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis is sufficient to justify initiating treatment. In patients with peripheral neuropathy suspected to be associated with sarcoidosis, sural nerve biopsy has a very low yield in establishing a definite pathological diagnosis. However, muscle biopsy may offer a better yield in establishing a definite diagnosis of inflammatory granulomatous myopathy.

CNS or PNS tissue biopsy is helpful in establishing a definitive diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. However, as for all invasive brain procedures, the decision to obtain meningeal, brain, or spinal cord tissue biopsy specimens should be based on the need to establish a pathological diagnosis essential for treatment in the absence of other clinical or pathological data that support the diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis. In the majority of cases, a diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis is sufficient to justify initiating treatment. In patients with peripheral neuropathy suspected to be associated with sarcoidosis, sural nerve biopsy has a very low yield in establishing a definite pathological diagnosis. However, muscle biopsy may offer a better yield in establishing a definite diagnosis of inflammatory granulomatous myopathy.Pathology

The hallmark of pathological changes in sarcoidosis is the presence of a noncaseating granulomatous inflammatory reaction. Multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytic infiltration are parts of the inflammatory tissue reaction (Fig. 96-5). In brain biopsy specimens, these changes are also characteristic, but a low frequency of giant cell or classic granuloma formation may be the main feature of some encephalitic forms in which marked mononuclear and lymphocyte infiltration predominate. Brain lesions associated with sarcoidosis frequently show a mixed inflammatory cellular profile with increased number of histiocytes, “foamy” macrophages, and both T and B lymphocytes.

Treatment Approaches

Treatment of Refractory Disease and of Relapsing-Remitting and Chronic Forms

Treatment of relapsing-remitting and chronic forms of neurosarcoidosis may require the use of alternative treatments such as immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory medications. The decision to use these medications should be based on the patient’s response to steroid therapy, the adverse effects of chronic use of steroids, and the clinical course of the disease. The major goal of therapy in relapsing-remitting and chronic forms of neurosarcoidosis is to limit the immune system reactivity that facilitates the development of granulomatous inflammatory lesions within the CNS or PNS. Immunosuppressant medications such as methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and mycophenolate mofetil have been used as alternatives to the long-term use of prednisone or as adjuvants to chronic steroid therapy.8 The introduction of anti–TNF-α modulators has provided a new potential treatment approach for neurosarcoidosis. The selection of these medications should be based on the patient’s individual assessment, because some of these medications can have serious side effects.

NEURO-BEHÇET’S DISEASE

Neuro-Behçet’s disease is the neurological manifestation of Behçet’s disease, a systemic disorder characterized by an inflammatory vasculopathy and manifested clinically by mucocutaneous lesions, uveitis, large blood vessel vasculopathies, and gastrointestinal problems. Behçet’s disease occurs worldwide, but foci of high prevalence are well known in the Far East, Middle East, and Mediterranean countries. Epidemiological studies have shown that neurological involvement is more frequent among men (13%) than among women (5.6%).9 As in the case of sarcoidosis, the etiological factors associated with Behçet’s disease remain elusive. The frequency of neurological manifestations of Behçet’s disease is highly variable; authors of clinical and autopsy-based studies reported a prevalence of neurological involvement of between 5% and 20%.10,11

Clinical Features

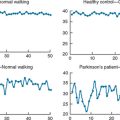

Patients with Behçet’s disease present with a variety of mucocutaneous, arthritic, ocular, and other systemic manifestations. Diagnostic criteria for the disease have been defined12 and include the presence of recurrent ulcerations that occur at least three times in one 12-month period, plus two of the following problems: recurrent genital ulceration, ophthalmic lesions (e.g., uveitis or retinal vasculitis), or dermatological lesions (e.g., erythema nodosum, papulopustular lesions, or acneiform nodules). The clinical manifestation of neuro-Behçet’s disease is highly variable and reflects the multifocal involvement of the CNS. Two major variants of neuro-Behçet’s disease are observed:13 a parenchymal (intra-axial) form, characterized by inflammation of small venous structures that produces focal or multifocal CNS involvement, and an extra-axial venous vasculopathy that produces venous sinus thrombosis. The parenchymal forms appears to be the most frequent manifestation (77% to 87% of cases) of neuro-Behçet’s disease,10,11 but both forms of the disease may overlap in some patients. PNS and myopathic forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease are relatively rare. PNS involvement manifests as acute or subacute polyradiculoneuropathies, including Guillain-Barré syndrome and sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathies. Myopathic forms manifest as necrotizing inflammatory myopathies. Like CNS involvement, PNS and myopathic involvement in in neuro-Behçet’s disease is associated with inflammatory vasculopathic changes.

Parenchymal (Intra-Axial) Forms of Neuro-Behçet’s Disease

The parenchymal forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease are heterogeneous and manifested clinically by a variety of symptoms and signs that reflect the focal or multifocal involvement of the disease. Headaches, multiple cranial nerve involvement, cerebellar dysfunction, tumor-like lesions, white matter disease, encephalopathies, and myelopathies are frequent clinical manifestations of this form of the disease. Many patients with parenchymal forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease are young, have supratentorial white matter and cortex involvement that may mimic white matter disease, or have ischemic lesions that may lead to misdiagnoses of multiple sclerosis or stroke. However, one of the most frequent manifestations of this form is subacute brainstem involvement that manifests clinically with multiple cranial nerve involvement and corticospinal and cerebellar dysfunction. Myelopathic manifestations represent 10% to 30% of the parenchymal forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease.

Nonparenchymal (Cerebrovascular) Forms of Neuro-Behçet’s Disease

The extra-axial, or nonparenchymal, forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease manifest frequently as venous sinus thrombosis, but cases of arterial occlusion and aneurysmal formation are occasionally seen. These forms are less frequent than the parenchymal forms and occur in 13% to 23% of patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease.10,11 The venous vascular thrombosis form has a frequent subacute manifestation, it is strongly associated with systemic major vessel disease, and appears to manifest earlier in the course of the disease.14 Headaches, signs of increase intracranial pressure, cranial nerve involvement, and neurological signs associated with hemorrhagic venous infarction are frequently observed in the cerebrovascular forms of neuro-Behçet’s disease.

Diagnostic Approaches

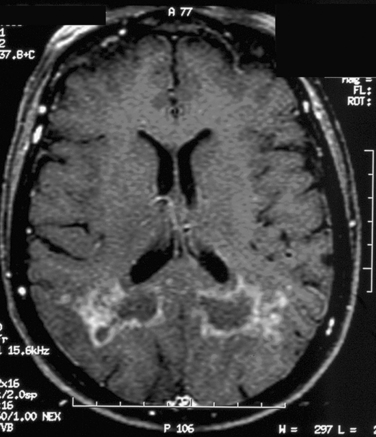

Patients with neurological manifestations who fit the diagnostic criteria for neuro-Behçet’s disease should undergo a careful assessment that includes neuroradiological assessment by MRI, CSF analysis, and other serological testing to rule out the potential presence of other disorders. Because neuro-Behçet’s disease may manifest with variable, multifocal, or relapsing-remitting symptoms, it is sometimes misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis. MRI of the brain and spinal cord is necessary to assess the magnitude and extension of the disease. MRI abnormalities include focal or multifocal lesions that frequently involve diencephalic and basal ganglia structures, the brainstem (pons and cerebellar peduncles), and subcortical white matter regions.15,16 Abnormalities observed in MRI studies reflect the ischemic, inflammatory, and vasculopathological nature of the disease and may exhibit varying degrees of contrast enhancement or ischemia-associated tissue changes. In contrast with multiple sclerosis, MRI abnormalities in periventricular white matter lesions are less frequent in neuro-Behçet’s disease. Diffusion-weighted MRI and magnetic resonance venograms may be helpful in the assessment of patients with suspected cerebrovascular or extra-axial forms of the disease. CSF studies are important for determining the magnitude of inflammatory reactions within the CNS and may demonstrate presence of pleocytosis with neutrophilic or lymphocytic predominance and increase of protein concentration. As it happens in neuroinflammatory disorders of the CNS, increase in the immunoglobulin G index and presence of oligoclonal bands may be seen in some patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease10,11; thus, these parameters should be evaluated carefully as criteria for differentiation with multiple sclerosis. Other imaging approaches such as positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography may be useful for assessing patterns of tissue perfusion and metabolism within the CNS. Serological testing to assess autoimmunity associated with rheumatological disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematous, vasculitis, or Wegener’s granulomatosis) should be completed in patients with suspected neuro-Behçet’s disease to rule out the potential presence of these disorders.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2003;361:1111-1118.

Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:397-407.

Siva A, Altintas A, Saip S. Behçet’s syndrome and the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:347-357.

Smith JK, Matheus MG, Castillo M. Imaging manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:289-295.

Stern BJ. Neurological complications of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:311-316.

1 Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885-1889.

2 Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2085-2091.

3 Moller DR, Chen ES. What causes sarcoidosis? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:429-434.

4 Luisetti M, Beretta A, Casali L. Genetic aspects in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:768-780.

5 Moller DR, Chen ES. Genetic basis of remitting sarcoidosis: triumph of the trimolecular complex? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:391-395.

6 Schurmann M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphisms in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: impact on disease severity. Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2003;3:233-243.

7 Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis—diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92:103-117.

8 Moller DR. Treatment of sarcoidosis—from a basic science point of view. J Intern Med. 2003;253:31-40.

9 Kural-Seyahi E, Fresko I, Seyahi N, et al. The long-term mortality and morbidity of Behçet syndrome: a 2-decade outcome survey of 387 patients followed at a dedicated center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:60-76.

10 Kidd D, Steuer A, Denman AM, et al. Neurological complications in Behçet’s syndrome. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 11):2183-2194.

11 Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasci B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet’s disease: evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behçet Study Group. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 11):2171-2182.

12 International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet. 1990;335:1078-1080.

13 Borhani HA, Pourmand R, Nikseresht AR. Neuro-Behçet disease. A review. Neurologist. 2005;11:80-89.

14 Tunc R, Saip S, Siva A, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis is associated with major vessel disease in Behçet’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1693-1694.

15 Lee SH, Yoon PH, Park SJ, et al. MRI findings in neuro-Behçet’s disease. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:485-494.

16 Akman-Demir G, Bahar S, Coban O, et al. Cranial MRI in Behçet’s disease: 134 examinations of 98 patients. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:851-859.