CHAPTER 6 Neuropathology of Meningiomas

DEFINITION

Cushing first coined the term “meningioma” to denote a primary tumor originating from cellular constituents of the meninges, thereby encompassing all primary, meningeal-based neoplasms.1 Over time, the term became limited to tumors arising from arachnoidal cap or meningothelial cells. Morphologically, the category covers a wide range of neoplasms, ones varying in grade from benign (WHO grade I) through atypical (WHO grade II) to malignant (WHO grade III). A lengthy list of descriptive terms has been appended to subtypes of meningioma, including, among others, meningothelial, fibroblastic, transitional, psammomatous, secretory, and microcystic. Only a handful is associated with characteristic laboratory findings or clinical behavior.2–4

Meningiomas are typically dura-based, often originating in areas where arachnoidal granulations reside. The majority occur in adults and are idiopathic in origin. Children are only occasionally affected.5,6 Only rare meningiomas occur after cranial radiation7–11 or arise in the setting of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). The latter disorder should be suspected when meningioma, particularly multiple lesions, occur in childhood and adolescence.12 Rare meningiomas are accompanied by other estrogen-dependent tumors, such as carcinomas of breast or endometrium.2

DEMOGRAPHICS

Meningiomas are the most common primary, intracranial, nonglial tumors as well as the most frequently occurring extraaxial neoplasms.13 Collectively, they comprise 20% of intracranial neoplasms,13 including 15% of symptomatic and 33% of asymptomatic lesions.13 Most meningiomas affect adults in middle and older age. In the pediatric population, they account for only 1.4% to 4% of intracranial tumors.13 Gender predilection typifies meningiomas. The 2:1 female-to-male ratio generally noted diminishes with age. Thus, in malignant meningiomas, the genders are also equally represented.13 The same is true of meningiomas encountered incidentally at autopsy study.

The reported annual incidence of meningiomas is approximately 2.3 to 3.1 per 100,000.13 In comparison, the annual incidence of meningiomas detected at autopsy is 3.9 to 5.3 per 100,000.14 The incidence of both symptomatic and asymptomatic meningiomas rises with age.13 One recent study showed 38.9% of meningiomas were asymptomatic15; this is particularly true in women and in individuals older than 70 years of age.14

The proportion of multiple meningiomas, a condition known as “meningiomatosis” when pronounced, is approximately 1% to 5% in surgical series.16 Such tumors occur more frequently in women and the elderly.13 On computed tomography (CT), they comprise 8% of meningiomas; the figure is 8% to 16% in autopsy studies of meningiomas.13 Although multiple meningiomas occur at relatively high frequency in the setting of NF2, it is of note that such patients may not have other characteristic features of the disease, such as multiple schwannomas.13 Nearly half of the patients with NF2 have a meningioma and that almost 30% have multiple lesions.13 Among the 5% of patients with meningiomatosis in one series, only 19% fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for NF2.16 Familial meningiomatosis unassociated with NF2 is extremely rare; only one case has been reported.16

SPECIFIC SITES

The majority of meningiomas are intradural and arise at intracranial, intraspinal, or orbital locations. Intracranial examples favor sites of arachnoidal granulations and produce increased intracranial pressure, including such symptoms of mass effect and focal neurologic deficits. In contrast to intraparenchymal tumors, such as gliomas and metastases, seizures are relatively uncommon in meningiomas.2

Neuroimaging usually demonstrates a globular, highly vascular, contrast-enhancing, dura-based tumor. A practical radiologic clue to the diagnosis is the “dural tail sign” due to a wedge-shaped, contrast-enhancing tongue of neoplastic or granulation tissue situated at the angle between tumor and underlying dura. Although an uncommon pattern, some meningiomas, particularly ones involving the sphenoid ridge form a carpet-like or “en plaque” lesion. One histologic subtype, the microcystic variant, is often associated with an intratumoral or peritumoral cyst formation.2 In some instances, meningiomas are almost entirely embedded within the brain and are associated with peritumoral edema.2

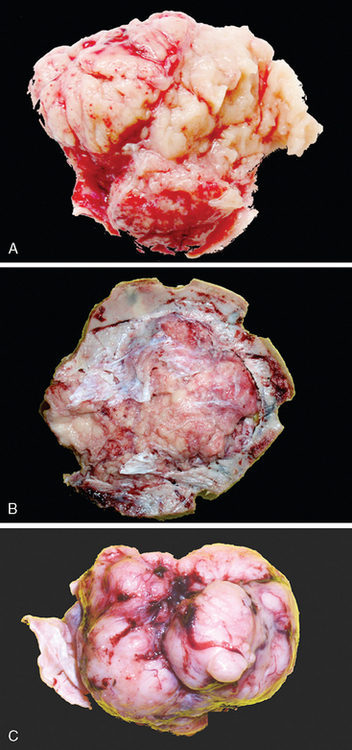

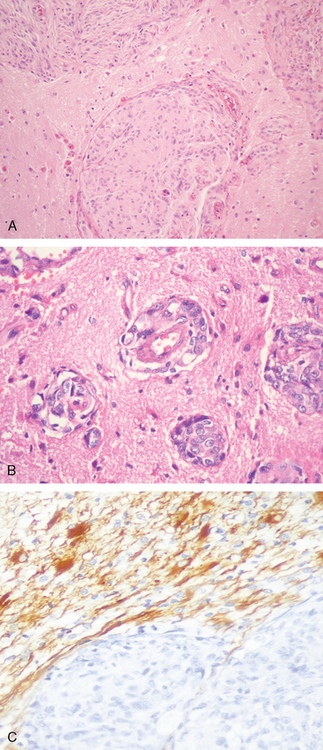

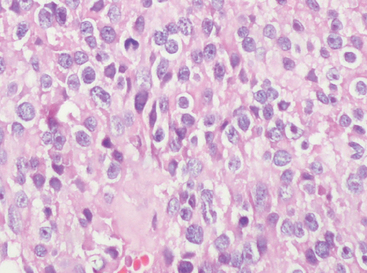

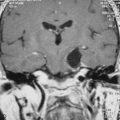

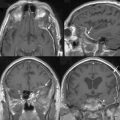

Neuroimaging is invaluable in the diagnosis of meningiomas. On nonenhanced CT images meningiomas are often isodense to gray matter, making them difficult to visualize. Calcifications are common and bright on CT scans.17 On MRI scan, most are isointense but may be partly hypointense when densely fibrotic and/or heavily calcified.18 As a rule, the higher the histologic grade of the tumor, the more frequent and extensive is peritumoral edema. For example, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas that attach themselves to the pia often provoke considerable cerebral edema.19,20 It is not surprising, therefore, that edema is more common in association with meningiomas having increased MIB-1 labeling indices.21 Brain invasive meningiomas show an irregular tumor–brain interface and often impressive edema (Fig. 6-1A), a reaction far less evident in grade I or II lesions.

Histologically, meningiomas often infiltrate the dura and may involve mesenchymal tissue, including the skull, galea, and subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 6-1B).

Bone infiltration induces cranial hyperostosis, which consists of bony spicules that radiate from the outer and inner tables. The scalp masses associated with hyperostotic meningiomas may be associated with either galea elevation or penetration and can be the presenting sign of disease.2

Histologically, choroid plexus owes its configuration to invagination of vessels, mesenchyme, and leptomeninges along the choroidal fissure. Thus, it is not surprising that meningiomas are encountered within choroid plexus stroma. Although infrequent, they involve the lateral,22 third,2 and even the fourth23 ventricles. Meningiomas involving the pineal region are rare.2

Orbital meningiomas originating from the optic nerve sheath are uncommon. Anatomically, only a small proportion of orbital meningiomas originate as intradural masses; others lie free within orbital soft tissues.2 Understandably, patients are presented with strabismus, ptosis, and visual disturbance.

Almost all spinal meningiomas are intradural and extramedullary. Many expand at the expense of the adjacent spinal cord and produce segmental neurologic deficits.2 The cervicothoracic level is most often affected. Nearly all tumors arise either ventral or lateral to the nerve root exit zone, areas wherein meningothelial cells are normally concentrated. Spinal meningiomas are rarely intramedullary. In contrast to intracranial meningiomas, spinal meningiomas rarely involve surrounding bone. The female predilection is much higher than that of intracranial lesions, the ratio being almost 10 to 1.2 Histologic meningioma subtypes with a clear proclivity for the spinal axis include the psammomatous and clear cell variants.

Another subset of meningiomas, either intracranial or intraspinal, is epidural in location. Although dura-based, their bulk lies outside the dura. Lastly, rare meningiomas arise within bone. Such intraosseous meningiomas usually affect the skull (diploic meningioma) where they presumably originate from meningothelial rests.2 Also among these are meningiomas of the ear (petrous bone) and temporal bone.24

Rare sites of occurrence of meningiomas include the sinonasal tract,25 skin, lungs,26 mediastinum and peripheral nerves.2 Such ectopic meningiomas are thought to originate in part by direct extension along soft tissue planes, whereas others are truly ectopic. For example, meningiomas in lungs and/or mediastinum presumably take their origin from discrete, microscopic nests of cells with histologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural characteristics of meningothelium. Molecular studies of microdissection specimens suggest that isolated pulmonary lesions may not be neoplasms, whereas multifocal examples may be true tumors or intermediate, precursor lesions.2,27,28

GROSS FINDINGS

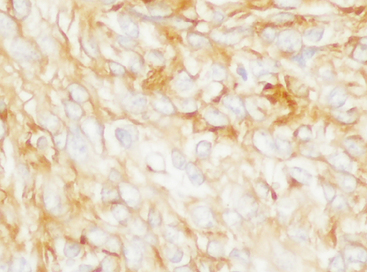

Most meningiomas are well delineated, soft to rubbery in consistency, and discrete with smooth or lobulated surfaces (Fig. 6-1C).

The attachment of meningiomas to dura is typically by a broad base.3,13,29–31 The majority are soft in texture, but fibrous meningiomas are decidedly more firm. The microcystic subtype may, in part, be grossly cystic and often shows intimate attachment to the brain surface. Invasion of underlying dura is a common finding. In contrast, meningiomas envelope but almost never invade blood vessels other than venous sinuses. Perivascular space involvement may, to some extent, facilitate extradural extension and soft tissue involvement. In addition, extension through bony foramina or fissures permits involvement of adjacent extracranial compartments, such as the orbit or skull base.2

Occasional meningiomas are coarse and grainy in consistency due to the presence of abundant microcalcifications termed “psammoma bodies.” Such tumors often occur in spinal dura or in the olfactory groove. In contrast, metaplastic bone formation is very uncommon, being most frequent in spinal examples. As noted in the preceding text, meningiomas infiltrating or penetrating bone stimulate remarkable hyperostosis. As previously noted at sites such as over the sphenoid wing, meningiomas grow carpet-like as “en plaque” meningioma.32,33 Such tumors pose an operative challenge. On occasion, heavy lipidization renders a tumor bright yellow. In contrast, rare metaplastic tumors with myxomatous features are gray and translucent.2

Meningiomas often compress adjacent brain but only infrequently show parenchymal invasion. As a rule, they push the leptomeninges before them, creating a margin that serves as a cleavage plane. Microcystic variants are somewhat of an exception, often being broadly attached to the pial surface. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, being larger than benign examples,34 often have a more extensive and irregular tumor–brain interface. Such tumors may not be cleanly removed, particularly if perivascular (Virchow–Robin) space involvement or cortical invasion is present. Recurrent tumors are also less well defined and are more likely to be adherent to the brain or to encase nerves and vessels.2

HISTOLOGIC SUBTYPING OF MENINGIOMAS

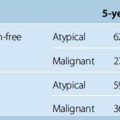

Although all meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells, they exhibit a wide variety of histologic appearances.3,29–33 According to the 2007 WHO classification, meningothelial, fibrous and transitional subtypes are most common. On balance, the majority of meningioma subtypes are grade I and follow an uneventful clinical course. Grade II (atypical) and grade III (malignant) examples are far more likely to behave in an aggressive manner. Nonetheless, metastases are rare. Histologically, grades II (atypical, chordoid and clear cell tumors), as well as grade II (anaplastic, papillary, and rhabdoid tumors) comprise the groups of intermediate and high-grade meningiomas. Compared to grade I tumors, those of grade II are 8-fold more likely to recur after gross total removal. Grade III lesions behave in a frankly malignant manner (Table 6-1).2,32,33 The issue of meningioma grading according to various histologic parameters is discussed in the text that follows.

TABLE 6-1 Histologic subtypes of meningiomas according to WHO Grade.

| Subtypes with low risk of recurrence and aggressive growth | ||

|---|---|---|

| ICD-O code | ||

| Meningothelial meningioma | WHO grade I | 9531/0 |

| Fibrous (fibroblastic) meningioma | WHO grade I | 9532/0 |

| Transitional (mixed) meningioma | WHO grade I | 9537/0 |

| Psammomatous meningioma | WHO grade I | 9533/0 |

| Angiomatous meningioma | WHO grade I | 9534/0 |

| Microcystic meningioma | WHO grade I | 9530/0 |

| Secretory meningioma | WHO grade I | 9530/0 |

| Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma | WHO grade I | 9530/0 |

| Metaplastic meningioma | WHO grade I | 9530/0 |

| Subtypes with greater likelihood of recurrence and/or aggressive behavior: Meningiomas of any subtype or grade with high proliferation index (4 mitoses/10 high-power fields) and/or brain invasion | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chordoid meningioma | WHO grade II | 9538/1 |

| Clear cell meningioma (intracranial) | WHO grade II | 9538/1 |

| Papillary meningioma | WHO grade III | 9538/3 |

| Rhabdoid meningioma | WHO grade III | 9538/3 |

Meningiomas show a wide variety of histologic appearances. Many are of no prognostic significance. Histologic features of grade II lesions vary and include both histologic patterns and tumors featuring specific parameters (see later). Simply finding occasional mitoses and pleomorphic nuclei does not indicate aggressive clinical behavior. Histologic parameters used to diagnose atypical meningiomas (see later) are applied independently of tumor subtype, although some patterns are, by definition, grade II or III. Although most meningiomas demonstrate features of at least one of the categories described below, mixed patterns are common. The recent 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of meningiomas is based largely upon the expression of relatively specific morphologic features.32,33

Histologic Meningioma Subtypes

Meningothelial meningioma

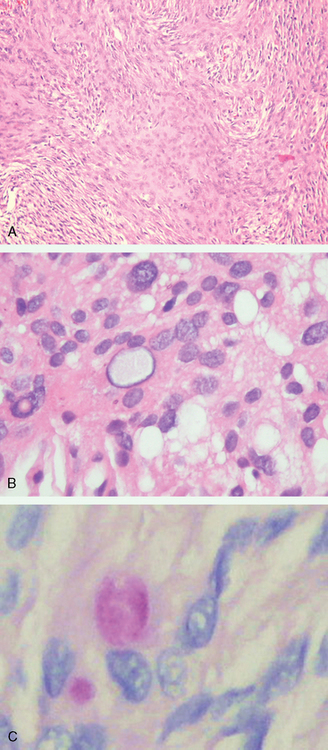

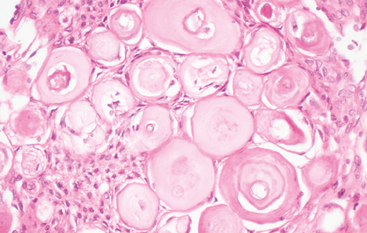

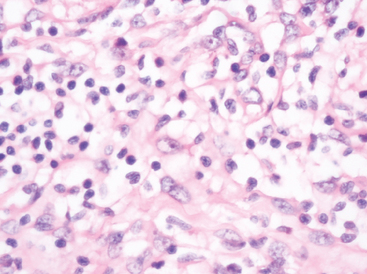

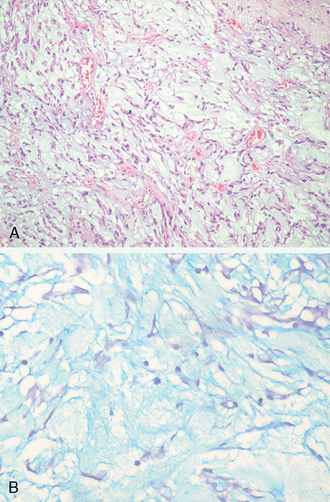

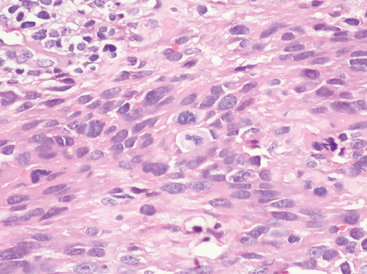

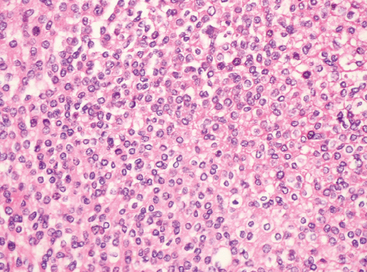

Once termed “syncytial meningioma,” the meningothelial variant is the most common and archetypic form of meningioma. It consists of varying sized lobules of neoplastic cells with indistinct borders (Fig. 6-2A).

The cells demonstrate classic cytologic features of meningothelium including round to oval nuclei, delicate chromatin, small solitary nucleoli, and variable numbers of nuclear-cytoplasmic inclusions surrounded by marginated chromatin. Glycogen containing, such inclusions can be found in many meningioma variants (Fig. 6-2B, C).

In small biopsy specimens, reactive meningothelial hyperplasia accompanying other processes may simulate meningioma. Florid examples are seen in association with optic nerve glioma, adjacent to tumors such as schwannoma, chronic renal disease, “arachnoiditis ossificans,” advanced patient age, and occasionally in association with diffuse dural thickening (“pachymeningitis”).35

Fibrous meningioma

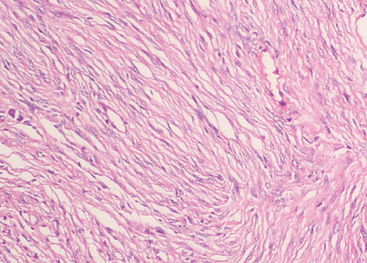

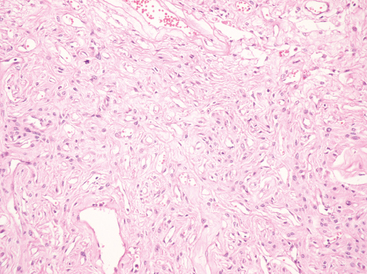

Fibrous meningiomas are relatively uncommon, particularly in pure form. The pattern is often partly represented in transitional meningiomas (see later). The fibrous variant consists of elongate, spindle cells forming parallel or storiform arrangements in association with variably collagen-rich matrix (Fig. 6-3).

Nuclei are often somewhat hyperchromatic and more elongated than those of the transitional meningiomas. Nuclear pseudoinclusions, whorls, and psammoma bodies are less frequent, but calcification of collagen bundles or of vasculature may be seen.2

Transitional meningioma

Featuring a combination of common findings, transitional meningiomas represent the prototypical meningioma. Architecturally, most are intermediate between meningothelial and fibrous lesions. In many tumors, the epicenters of lobules appear syncytial, whereas elongate, more fibrous cells stream from their peripheries. Eye-catching tight whorls are a regular feature as are scattered psammoma bodies (Fig. 6-4A, B).

Psammomatous meningioma

This designation is applied to meningiomas containing hyperabundant psammoma bodies (Fig. 6-5).

The term “psammomatous” is not limited to tumors of a specific histologic subtype, but most tumors are transitional. Psammoma bodies, when abundant, may become confluent, forming irregular calcified masses and occasionally being associated with bone. Rare tumors are nearly replaced by psammoma bodies, meningothelial cells being hard to find. As previously noted, such tumors favor the spinal meninges and/or olfactory groove and usually affect middle-aged women.33 As a rule, psammomatous tumors are biologically benign (WHO grade I).2

Angiomatous meningioma

Meningiomas of almost any type can be highly vascularized, but most are basically meningothelial or transitional in pattern. The nonspecific term “angiomatous meningioma” is applied to such vessel-rich tumors (Fig. 6-6).

The vascular channels vary in morphology from small to large and from thin-walled to thick and hyalinized. The vast majority of angiomatous tumors are clinically and histologically benign, despite moderate to marked degenerative nuclear atypia. Depending on vessel size and architecture, the differential diagnosis includes both hemangioblastoma and vascular malformations. The former comes into consideration due to frequent xanthic change. The designation angiomatous should not be equated with the now obsolete term “angioblastic meningioma,” which was once applied to hemangiopericytoma. Accompanying cerebral edema may be out of proportion to tumor size.33

Microcystic meningioma

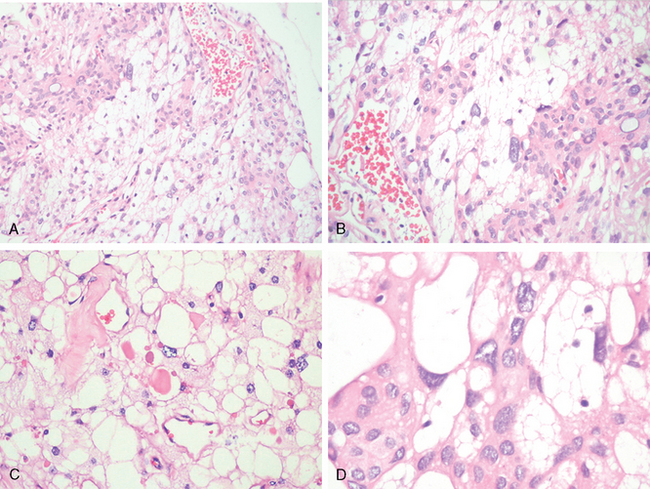

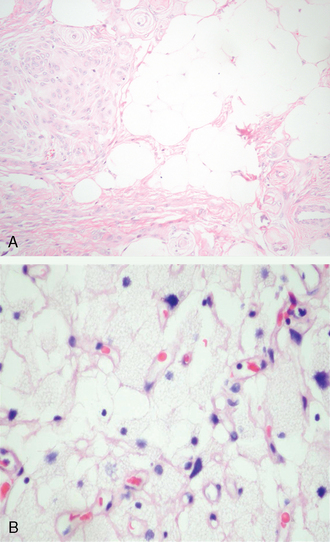

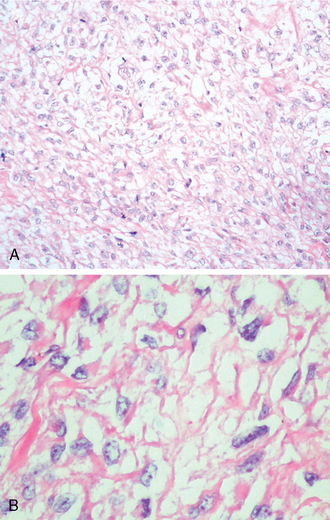

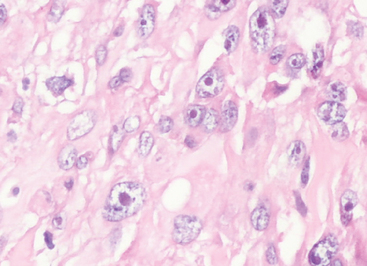

Histologically, this distinctive variant of meningioma is characterized by cells with thin, elongate processes encompassing intercellular microcysts containing pale, eosinophilic mucoid fluid. By and large, they are hypo- to moderately cellular, exhibit a loose texture, and feature considerable vascular hyalinization.36,37 The neoplastic cells often show some degrees of xanthomatous change (Fig. 6-7A, B) and occasional brightly eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive, hyaline droplets (Fig. 6-7C).

Given its vascularity, foamy cells, and scattered large pleomorphic nuclei (Fig. 6-7D), this type of meningioma can also mimic hemangioblastoma.

The distinction rests upon tumor location and immunohistochemistry: epithelial membrane antigen (EMA)- and progesterone receptor positivity as well as lack of neuron specific enolase (NSE), inhibin, and aquaporin38,39 staining.

No prognostic significance is attached to the microcystic pattern, although this tumor is more likely than other grade I lesions to attach broadly to the surface of the brain and to be edema associated.37 They are also over-represented among meningiomas with large cysts.2

Secretory meningioma

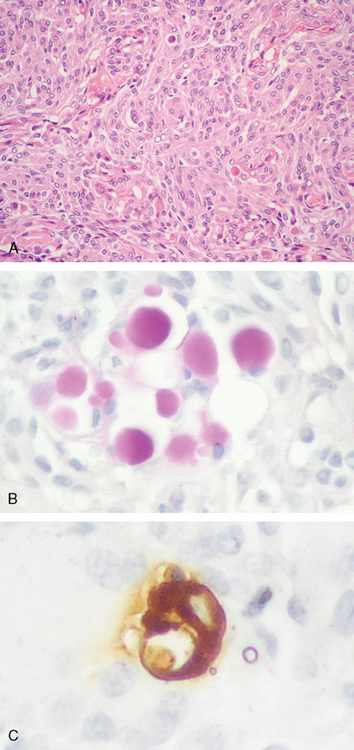

The hallmark of this tumor variant is the presence of focal epithelial differentiation in the form of intracellular lumina containing discrete, brightly eosinophilic, PAS-positive secretion in the form of so-called “pseudopsammoma bodies.” These are usually seen in tumors with basically meningothelial or transitional histology (Fig. 6-8A).

Secretory meningiomas occur mainly in women and frequently originate over the frontal lobes or sphenoid ridge.40–43 Pseudopsammoma bodies must be distinguished from the larger, laminated, basophilic, and calcium-rich psammoma bodies that generally originate at the centers of whorls. Pseudopsammoma bodies are intracellular, often multiple within a single cell, red rather than blue, solid rather than laminated, and are independent of whorls. Further, they are immunoreactive for CEA and are surrounded by pancytokeratin-positive cells (Fig. 6-8B, C).

Lastly, pseudopsammoma bodies might be misdiagnosed as microcalcifications. Mast cells may be particularly numerous, and peritumoral edema can be significant.33,44

No prognostic significance is attached to secretory meningioma, although they are nearly always of WHO grade I and associated with a favorable prognosis. Peritumoral edema is prominent around some examples.43 Elevated serum levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) have been reported to increase with tumor growth and fall after resection.45

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma

This rare meningioma variant features extensive chronic inflammatory infiltrates. What prompts this impressive lymphocyte and plasma cell response is unclear (Fig. 6-9).46

In any event, they dominate the lesion and often obscure the neoplastic component. Russell bodies are frequent and germinal centers may be present.2 The very existence of lymphoplasmacytoid meningioma as a distinct clinicopathologic entity has been questioned, since its behavior often resembles that of an inflammatory process.47 Systemic hematologic abnormalities, including hyperglobulinemia and iron refractory anemia have been documented in some cases.2,33

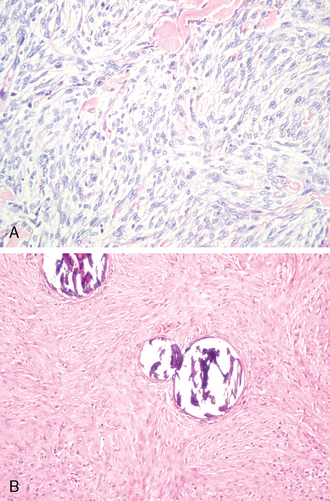

Metaplastic meningiomas

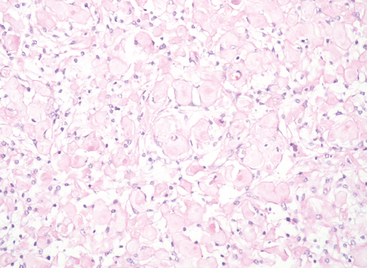

Metaplastic variants, in addition to showing a baseline meningotheliomatous or transitional pattern, feature various mesenchymal elements including bone, cartilage, fat (Fig. 6-10A), and myxoid or xanthomatous tissue48 (Fig. 6-10B).

These may occur singly or in combination. Bone formation may supervene in tumors with abundant psammoma bodies. Bone may also arise in mineralization of stromal fibrous tissue. Metaplastic bone should be distinguished from reactive bone overrun by invasive meningiomas. Whereas xanthomatous change is usually a focal feature of meningiomas, it occasionally dominates the histologic picture. In being an accumulation of microvascular fat in meningothelial cells, it differs from equally uncommon adipose cell metaplasia. Myxoid metaplasia is rare.2,33 Whether meningiomas showing oncocytic transformation can be considered metaplastic is unsettled; in any event, such rare tumors are thought to be relatively aggressive.48–51

Rare meningiomas exhibit perivascular proliferation of pericytes, a feature that may be prominent.52 Such tumors may be associated with inordinate peritumoral edema.52 Rare meningiomas feature glandular or pseudoglandular differentiation.2 The clinical significance of these alterations, if any, is unclear.33

A rare form of “collision” tumor affecting the nervous system consists of a meningioma intimately associated with a glioma.2 While coincidence seems responsible in most cases, there has been speculation that the meningioma, or for that matter various mesenchymal tumors, may induce the glioma formation.53 A spatially similar meningioma–schwannoma association has also been documented, affecting the cerebellopontine angle in the setting of NF I.54

Unusual morphologic variations in ordinary meningiomas

As a reflection of the wide morphologic spectrum encountered in meningiomas, rare examples are difficult to classify. More pattern deviations than true variants, these include meningioma with widespread, sclerosing (Fig. 6-11), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-expressing (doubtful) and granulofilamentous inclusion-bearing features,49,55–57 and tumors featuring petal-like tyrosine crystals are a rare finding in meningiomas.58

The majority of tumors once termed “pigmented meningiomas” are now known to be melanocytomas.59,60 Lastly, recruitment of melanocytes from the adjacent meninges into the substance of a true meningioma accounts for the dark pigmentation of rare examples.33,61 On occasion, meningiomas play host to metastatic carcinoma (Fig. 6-12A, B)62–64 or leukemia.65

HISTOLOGIC PATTERNS ASSOCIATED WITH AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR

WHO Grade II (Atypical) Meningioma

Atypical or WHO grade II meningiomas, also termed “atypical” are defined by increased mitotic activity or three or more of the following histologic features: hypercellularity, small cells transformation, macronucleoli, uninterrupted patternless growth (“sheeting”), and foci of spontaneous or geographic necrosis.66 Increased mitotic activity is defined as 4 or more mitoses per 10 high-power (×40) fields (defined as 0.16 mm2).66 Compared to WHO grade I tumors, the above criteria have been shown to correlate with 8-fold higher recurrence rates, despite gross total resection.66 Alternative grading approaches had previously been devised but have been supplanted by the WHO approach. These included (1) identifying individually scored parameters to arrive at a sum67 and (2) simply combining the findings of hypercellularity with 5 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields.34 By any definition, atypical meningiomas often have moderately increased MIB-1 labeling indices.2,33

Chordoid meningioma

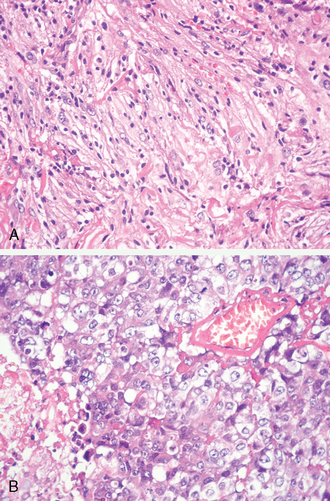

This uncommon meningioma variant consists predominantly of tissue superficially resembling chordoma, replete with cords or trabeculae of eosinophilic, sometimes vacuolated cells in an abundant, extracellular mucoid matrix68,69 (Fig. 6-13A, B).

Although occasional examples are entirely and overtly chordoid at presentation, many chordoid tumors evolve from more conventional meningiomas. If present, meningothelial or transitional components with whorls and psammoma bodies are infrequent in tumors with advanced chordoid change. The prognostic significance of merely focal chordoid change is uncertain. The recent classification by WHO 2007 emphasizes that the diagnosis should be made only when the pattern predominates.33 Chronic inflammatory infiltrates, often patchy, may be seen. Chordoid meningiomas are typically bulky, supratentorial tumors exhibiting a high rate of recurrence after subtotal resection. Thus, by definition, the tumor is a WHO grade II lesions.69 Very infrequently, patients have associated hematological abnormalities, such as Castleman’s disease.33

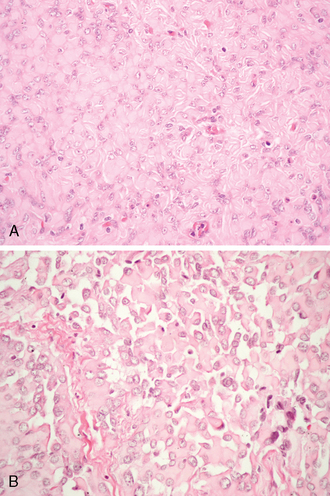

Clear cell meningioma

This rare meningioma variant shows a proclivity for the cerebellopontine angle, lumbosacral meninges, and cauda equina region; not all are dura-based.2 It may affect both children and young adults and consists of cells with clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm (Fig. 6-14A).23,69–71 Thus, the tumor is strongly PAS-positive and diastase-labile.

The cells are disposed in a largely patternless manner. Whorl formation, if present, is vague at best. Psammoma bodies are lacking. Blocky perivascular and interstitial collagen deposition (Fig. 6-14B) is often a conspicuous feature and may obscure the cellularity.

Unlike chordoid meningiomas that often feature a WHO grade I meningothelial element, clear cell meningiomas are typically pure in type. Despite uniform, cytologically bland nuclei and low proliferative activity, clear cell meningiomas show a significant tendency to recur. Occasional examples show limited cerebrospinal spread.33,72 Thus, they are considered WHO grade II.

Rhabdoid meningioma

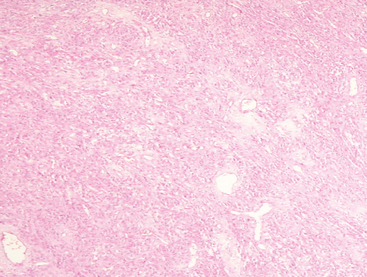

This very uncommon meningioma variant is characterized by clusters or sheets of rhabdoid cells with eccentric nuclei, often open chromatin and nucleolar prominence. The rhabdoid inclusions consist of eosinophilic aggregates of often whorled intermediate filaments. Fibrillary or waxy-appearing on H&E stain, the rhabdoid change may be a focal or generalized feature (Fig. 6-15A).73–76

Such rhabdoid cells resemble those occurring in rhabdoid tumors at other sites, such as the kidney.76 Similar cells are also seen in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the brain.77 Almost all rhabdoid meningiomas exhibit an elevated mitotic rate and/or other prognostically unfavorable histologic features. Unlike atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors, malignant rhabdoid tumors and classic meningiomas, losses of INI1 protein expression are uncommon in both rhabdoid meningiomas and secondarily rhabdoid tumors.78

As in chordoid meningioma, the key features of rhabdoid tumors may be become increasingly evident with tumor recurrences. The 2007 WHO classification suggests that the diagnosis should be made only when the pattern “predominates.”33 When faced with only focal rhabdoid features, the observation must be documented, although the behavior of such tumors remains to be determined.33 Rhabdoid meningiomas often undergo an aggressive clinical course and correspond to WHO grade III.74,75 Occasional tumors show combined features of rhabdoid and papillary meningioma (Fig. 6-15B).2

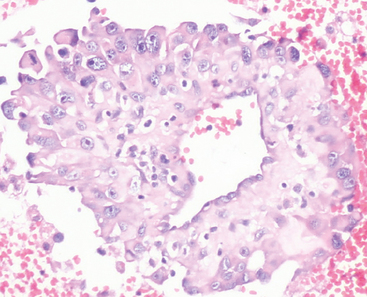

Papillary meningioma

Papillary meningiomas are rare, sometimes pediatric lesions.5,33,79 Scattered mitoses are often present. Their distinctive morphologic feature is perivascular orientation of tumor cell mimicking the perivascular pseudorosettes of ependymoma (Fig. 6-16).33,79,80

In contrast to ependymoma, the processes of papillary meningioma cells more closely approximate the vessels and are often separated by short, delicate reticulin fibers radiating in a perivascular, stellate pattern. The term papillary meningioma should be reserved for this variant and not applied to meningiomas in which pseudopapillary structures result from artifactual dehiscence of tissue during processing or ones in which necrosis results in the formation of viable, perivascular cuffs of neoplastic cells. As in rhabdoid meningioma (see earlier), the papillary pattern often increases in extent with recurrences. Invasion of the brain has been noted in 75% of cases, recurrence in 55%, metastasis in 20%, mostly to lung, and death of disease in roughly half.79,81 Considering their aggressive clinical behavior,79 papillary meningiomas are considered WHO grade III based on their histologic pattern alone.5,33,80 As a historical note, Cushing and Eisenhardt originally recorded this uncommon variant in 1938 in their patient Dorothy May Russell, who underwent 17 operations for the relief of an intracranial meningioma and she was proven having pulmonary metastases at autopsy.1

WHO Grade III (Anaplastic, Malignant) Meningioma

A meningioma exhibiting frankly malignant histologic features far in excess of the abnormalities present in atypical meningioma is referred as anaplastic. These include either obviously malignant cytology resembling that of carcinoma, melanoma or high-grade sarcoma, or a markedly elevated mitotic index (20 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields (defined as 0.16 mm2).81 Tumors that meet the above criteria correspond to WHO grade III and are often fatal, with an associated median survival of less than 2 years.81 As noted earlier, brain invasion alone is not sufficient for a diagnosis of anaplastic meningioma.81 Because malignant progression of meningiomas, like that of gliomas, is a continuum of increasing atypia and mitotic activity, tumors with features mediate between ordinary atypical and anaplastic meningiomas may occasionally be encountered.33 In such cases, we lean heavily on mitotic indices to draw a distinction.

HISTOLOGIC GRADING

The grading of meningiomas has evolved from the simple “brain invasion equals malignancy” approach to a multiparameter approach that assigns grades on the basis of tumor histologic pattern subtype and on a set of specific histologic features.3 While not accepted as a criterion in the WHO meningioma grading system, the MIB-1 index may be useful in confirming tumor grade and therefore in prognostication.

The recent 2007 WHO grading system of meningiomas is the culmination of clinicopathological studies from many institutions that have identified histologic grading parameters and histologic subtypes with more aggressive behavior as shown in Table 6-2.33,81,82 The latter include chordoid, clear cell, papillary, and rhabdoid variants. Oncocytic meningiomas, although rare, may also be more aggressive.50,51

| Grade I (“typical”) meningioma: meningioma without histologic features or patterns of grade II or III lesions |

|---|

| Grade II (“atypical”) meningiomas |

| With brain invasion, and/or |

| Four or more, but fewer than 20 mitoses per 10 high power fields, and/or |

| Three or more of the following: |

| Increased cellularity |

| Small cell change |

| Prominent nucleoli |

| Loss of architecture (“sheeting”) |

| Necrosis not explainable by preoperative tumor embolization, and/or |

| Chordoid or clear cell subtype |

| Grade III (“anaplastic”) meningiomas |

|---|

| Overt anaplasia resembling carcinoma, melanoma, or sarcoma, and/or |

| Twenty or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields, and/or |

| Rhabdoid or papillary subtype |

Features of WHO Grade II (atypical) meningioma

Brain invasion

Although not truly encapsulated, typical meningiomas have a smooth outer surface and a noninvasive relationship to the underlying brain. By definition, invasion of the brain is present when cohesive tongues of neoplastic tissue in continuity with the main tumor break through the pia to infiltrate underlying cortex (Fig. 6-17A).

Inspection of the outer surface of large tumors often shows small detached fragments of cerebral cortex attached to the pial surface of a meningioma. This and involvement of perivascular (Virchow–Robin) spaces should not be confused with brain invasion (Fig. 6-17B).

Assessing the relationship of a meningioma to the brain is facilitated by GFAP staining, since it detects tongues and islands of overrun brain tissue that are easily overlooked on routine histology. Brain invasive tumor often incites exuberant reactive gliosis (Fig. 6-17C).3,33

Infiltration of dura, bone, and even extracranial soft tissue may have little clinical impact in resectable lesions affecting the cranial vault but has a prognostically unfavorable effect in tumors involving the skull base. Invasion may be a worrisome finding at other locations as well. For example, parasagittal lesions often infiltrate and ultimately may occlude the superior sagittal sinus. If sufficient collaterals do develop, the affected sinus may be surgically sacrificed without resultant cortical infarction.2,3,33 Cavernous sinus involvement also carries significant morbidity.

Increased mitotic rate

The number of mitoses in meningiomas varies greatly from case to case. Whereas they may be difficult to find in otherwise classic, well differentiated or WHO grade I lesions, on occasion, mitoses are abundant in tumors lacking any other features of atypia (Fig. 6-18).

By definition, 4 or more (but fewer than 20) per 10 high-power fields indicates WHO grade II, whereas 20 or more satisfies the requirement for grade III (anaplastic meningioma).2,33 The two distributions form a bimodal curve; few tumors have 15 to 19 mitoses/10 HPF.

Sheeting architecture

Loss of lobularity or other distinctive, low-power patterns and their replacement by diffuse growth is referred to as “sheeting” (Fig. 6-19). It is frequently associated with other histologic features of atypia. Considerable subjectivity surrounds this feature; as a rule, at least a full low-power (×4) fields should be involved.

Nucleolar prominence

Whereas nucleoli in typical grade I meningiomas are small but distinct, they become prominent in grade II and grade III lesions, often locally and rarely widespread (Fig. 6-20). In addition, they may appear violaceous.

Increased cellularity

Although this feature can be quantified by determining the number of nuclei along a given diameter of a microscopic field, cellularity is generally assessed subjectively as being significantly greater than that of typical grade I meningiomas (Fig. 6-21).

Small cell change

Small cell change refers to patchy, often multifocal regions in which both overall cell and nuclear size are reduced (Fig. 6-22).

Necrosis

Necrosis usually takes the form of small foci, sometimes surrounded by pseudopalisading of viable cells. Geographic necrosis, particularly when widespread, is less common and associated with high-grade tumors (Fig. 6-23A).

Large, geographic zones of necrosis may be seen, particularly as a result of preoperative embolization. These typically appear acute and monophasic (Fig. 6-23B).

In such instances, embolic material is readily evident in vessels.82 Inasmuch as embolized tumors are often large, aggressive and WHO grade II (atypical), the finding of small foci of spontaneous necrosis as well as mitoses is no surprise.82 Nonetheless, mitoses and an elevated MIB-1 index are often present in relation to embolized perinecrotic regions. Such lesions might be overgraded if the changes resulted from treatment.83,84 If, however, large tumor size and atypia was what prompted embolization, such lesions could be meaningfully graded using the same criteria as are applied to nonembolized lesions.2,33

Cell Proliferation and Ploidy

Mitotic activity

In general, proliferation of tumor cells increases in quantity in benign through atypical to anaplastic (malignant) meningiomas. Mitotic indices roughly correlate with volumetric tumor growth rate.85 Significant differences in mitotic indices (total counts per ten high-power fields) are seen between tumor grades: 0.08 ± 0.05 in benign, 4.8 ± 0.9 in atypical, and 19 ± 4.1 in malignant tumors.86

MIB-1abeling

Although determination of MIB-1 labeling indices is not part of WHO grading of meningiomas, there is a prognostically significant and inverse relationship between MIB-1 indices and outcome.87,88 Nonetheless, as in the case of mitoses, MIB-1 labeling indices show a highly significant increase from WHO grade I or benign (mean, 3.8%), through grade II or atypical (mean, 7.2%), to grade III or anaplastic meningiomas (mean, 14.7%).86 Indeed, some studies suggest meningiomas with MIB-1 labeling indices greater than 4% show a risk of recurrence similar to that of WHO grade II or atypical meningioma, whereas those with indices greater than 20% are associated with death rates analogous to those of grade III or anaplastic meningioma.81,88 Although the method is appealing, differences in technique and interpretation from one laboratory to another make it difficult to apply firm cutoff values based on their results. Expected overlaps in values between tumors that do and do not recur detracts from the value of the technique.89 Although there are no approved thresholds which, when exceeded, mandate a grade II or III designation, a level of approximately 4% or more in gross-totally resected tumors has been associated with reduced recurrence-free survival.88 Mean values for grade I, II, and III tumors in the study of Perry and colleagues, based on gross totally resected tumors were 7% to 25%, 29% to 52%, and 50% to 94%, respectively.66,81 A similar level, greater than 3%, was found to be prognostically unfavorable in yet another study.90 As mentioned earlier, MIB-1 indices can be higher around foci of necrosis83,84 although the significance of the observation has been debated.36,82

With respect to proliferation indices, tissue sampling is also an issue. Should one attempt an overall MIB-1 estimate by counting random fields or do counts in areas with highest indices? Two studies shed light on the issue.87,91 When a random sampling method was employed, the mean MIB-1 indices were 1.15, 3.33, and 9.45 for meningioma grades I, II, and III, respectively.87 As predicted, higher levels of 2.2, 5.5, and 16.3 were found when the areas of maximal labeling areas were selected. Interestingly, the random field approach best correlated with outcome.

Ploidy

Flow cytometric studies have demonstrated the approximately equal frequency of occurrence of diploid and aneuploid meningiomas, as well as significant correlations between aneuploidy and nuclear pleomorphism, high cellular density, mitotic activity, infiltration of brain and soft tissue, and recurrence.33

Individual Features of WHO Grade III (Anaplastic, Malignant) Meningioma Anaplasia

Most meningiomas are, and remain, WHO grade I or, at the most, become grade II or atypical. Only infrequently do they acquire features fully justifying the designation anaplastic. As stated earlier, most grade III or anaplastic meningiomas are designated as such on the basis of increased mitotic activity (>20/10 high-power fields) rather than on cytologic features of carcinoma, melanoma, or sarcoma. Necrosis is almost always present in such tumors. Some meningiomas transit from atypical to anaplastic over time, as sequence of events associated with marked increase in proliferative activity and loss of the meningothelial phenotype.2,3,33 Only a minority is grade III or anaplastic de novo.

Other features

Other factors associated with a less favorable clinical outcome include subtotal extent of resection and loss of progesterone receptor immunostaining.92,93 Both are associated with an increased likelihood of recurrence. Grading in the context of prior embolization is complicated by the fact that embolization is associated with augmented nucleolar size, mitotic activity, and MIB-1 rate. Such lesions, in concept, could be overgraded, although one detailed analysis concluded that the lesions could be meaningfully graded using the same criteria as nonembolized lesions.33,82

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL FINDINGS

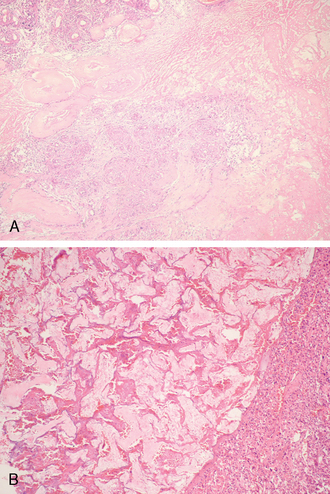

The most diagnostically useful marker of meningioma is membranous immunoreactivity for EMA (Fig. 6-24).2,89

Of basic meningioma subtypes, staining may be more marked in meningothelial and transitional lesions than in fibrous tumors. Variable cytoplasmic staining as well as some membrane accentuation may be seen in Schwann cell tumors as well, an important differential diagnostic entity.2,3,33 To complicate matters further, approximately 20% of meningiomas are reactive for S-100 protein staining being most frequent in the fibrous variant.2,77 Chordoid meningiomas show only patchy EMA staining. In accord with the arachnoid origin, the lesions are immunoreactive for the gap junction proteins connexin 26 and 43.94 Diffuse immunoreactivity for vimentin, a nondiagnostic feature in view of the expansive differential diagnosis, is seen in all forms of meningioma. Cytokeratin reactivity is typically seen in secretory meningiomas, staining being limited to cells immediately surrounding pseudopsammoma bodies.2,33 Both these cells and the pseudopsammoma bodies are positive for CEA.2,3,33 Interestingly, these same cells are usually negative for vimentin. Many other meningiomas are also immunoreactive for cytokeratins. Staining depends on the specific keratin sought and tumor subtype. For example, in one study, most meningiomas were immunoreactive for CK18, whereas none were positive for CK20.95 In this same study, anaplastic meningiomas showed the same profile.95 Yet another study found frequent AE1/AE3, CAM5.2 and pankeratin reactivities in “malignant meningiomas.”96 Claudin-1 has also been found to be a useful diagnostic marker in some studies.97 This remains to be confirmed in that it is a marker of tight junctions, not desmosomes. Another potentially useful marker that requires further study is the progesterone receptor.33

Although meningiomas are generally GFAP negative, there are reported exceptions, particularity filament-rich rhabdoid lesions wherein scattered cells may show some cytoplasmic staining.75,88,98,99 In that intermediate filament-rich cells do occasionally show nonspecific uptake of a variety of antibodies, this infrequent finding is considered of no diagnostic significance.

Immunoreactivity for progesterone receptors is the rule in WHO grade I and II meningiomas, it becomes less prominent with increase in grade.92

ULTRASTRUCTURAL FINDINGS

Diagnostically useful ultrastructural features of meningioma include (1) abundance of intermediate filaments (vimentin), (2) complex interdigitating cellular processes, particularly in meningothelial variants, and (3) desmosomal intercellular junctions. These cell surface specializations as well as intermediate filaments are few in fibrous meningiomas, with the cells separated by collagen. Given the abundance of collagen, fibrous meningiomas assume a distinctly mesenchymal appearance. Secretory meningiomas feature single or multiple lumina within meningothelial cells. Their surfaces are lined by short apical microvilli and enclose electron-dense, rather amorphous secretions. Microcystic meningiomas feature long, desmosome-linked cytoplasmic processes enclosing an intercellular, electronlucent matrix. Large cytoplasmic lysosomes (hyaline droplets) may also be seen in this variant.33

CYTO- AND MOLECULAR GENETICS

A critical and early genetic event responsible for NF2-associated tumors, both meningiomas and ependymomas,93,100,101 as well as for a proportion for sporadic lesions is inactivation of the NF2 gene on chromosome 22q12.93,102,103 Loss of merlin expression, its gene product, results.93,103 The cytogenetic equivalent is loss, usually monosomy, of chromosome 22.104,105

Beginning with most grade I lesions with normal karyotypes or monosomy 22, a spectrum of molecular and cytogenetic changes are seen in meningiomas. While both losses and gains occur, most attention has been directed at the former. How these alterations relate to tumor progression is unclear, but abnormalities on 1p, 14q, 18q, and 22q19, among others, may be related to tumor progression.104–107 Candidate genes such as p16 on 9p have been evaluated.106–108 Abnormalities on 9p2l, 6q, 10, and 17q may correlate with anaplasia.102,106,108–110

Meningiomas were among the first solid tumors recognized as having cytogenetic alterations, the most consistent change being deletion of chromosome 22.105 Interestingly, the incidence of NF2 mutations is substantially higher in fibroblastic and transitional meningiomas than in the meningothelial subtype.102,103 In general, karyotypic abnormalities are more extensive in atypical and anaplastic (malignant) meningiomas.109,111 Among the other cytogenetic changes associated with meningioma, deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1112 and loss of chromosomes 6, 10, 14, 18, and 19 are the most frequently seen.105,112 Molecular genetic findings indicate that approximately half of meningiomas have allelic losses that involve band q12 on chromosome 22.33 In addition, atypical meningiomas often show allelic losses of chromosomal arms 1p, 6q, 9q, l0q, 14q, l7p, and 18q, suggesting that progression associated genes reside here.103,107,109,112–114 These alterations, with more frequent losses of chromosomes 6q, 9p, 10, and 14q, also occur in anaplastic meningiomas. Chromosomal gains noted in higher grade meningiomas include primarily chromosomes 20q, 12q, 15q, lq, 9q, and 17q.33

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

With respect to WHO grade III (anaplastic) meningiomas, the morphologic criteria have also been developed in the WHO grading scheme. The rate of recurrence in anaplastic meningiomas is approximately 50% to 95%.34,66,81,115 Malignant histologic features are known to be associated with short survivals, with the median survival less than 2 years in one series.81 Recurrence rates in WHO grade I lesions are approximately 5 to 25%, whereas in atypical tumors, it is approximately 30% to 50%.34,66,81,115

As previously noted, the loss of progesterone receptor immunoreactivity is seen in association with higher histologic grade. Thus, a lack of progesterone receptors is associated with the prognosis and is a significant factor in recurrence and survival. The analyses based upon progesterone receptor status, mitotic indices, and multivariate analyses based on lack of progesterone receptor staining, mitotic activity greater than 6, and malignant (WHO grade III) status showed this combination to be a significant predictor of poor outcome.92,116

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hemangiopericytoma

Both histochemistry and immunohistochemistry aid in the differential diagnosis. Reticulin staining is useful because intercellular reticulin is frequent in hemangiopericytoma but generally lacking meningiomas. Reactivity for EMA when seen is limited to frequently seen, ill-defined loose-textured zones. This may be confusing because positivity may be scant or absent in highly atypical or anaplastic meningiomas.2,33,117

Solitary Fibrous Tumor

This tumor, only recently described as occurring in the central nervous system (CNS), may resemble fibrous meningioma but features brightly eosinophilic bands of collagen and lack of both whorls and psammoma bodies. Diffuse immunoreactivity for CD34 and bcl2 as well as CD99, are diagnostically useful clues.2,118

Hemangioblastomas

Hemangioblastomas rarely arise supratentorially but may be confused with xanthomatous metaplastic meningiomas. The common denominator is vacuolated cells, variable nuclear pleomorphism and prominent vascularity. Unlike the meningioma, which features some degree of membranous EMA staining, hemangioblastomas are usually reticulin-rich due to abundance of capillaries (reticulin variant) and are uniformly reactive for S-100 protein, neuron specific enolase, and most particularly for inhibin and aquaporin.119,120 Variable GFAP staining may also be seen in hemangioblastoma, particularly in the cellular variant.2,33

Metastatic Carcinoma

The characteristic, grossly globular configuration typical of dural metastatic carcinoma is easily confused with meningioma, but carcinoma remains a consideration only in meningiomas with advanced anaplasia. Histologic parameters such as nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia alone are of limited use in differential diagnosis. Even benign meningiomas may contain bizarre cells with atypical nuclei, but such tumors lack or exhibit only sparse mitotic activity. Cytologic preparations are of value since most meningiomas, even ones malignant, exhibit some meningothelial features, including nuclear–cytoplasmic inclusions, wrapping of cells, and so forth. These quickly dispel consideration of a malignancy when lack of mitoses is appreciated. Immunostaining for EMA is of no use in distinguishing meningioma and metastasis, but reactivity is usually more intense in carcinomas. Cytokeratins, although infrequently expressed in grade I meningiomas, can be appreciable in grade III variants, although CK20 reactivity tends to be absent.95 Some epithelial markers, such as BerEP4 may also aid in identifying carcinoma.96 Aside from its presence in secretory meningioma, CEA is generally limited to carcinomas. Progesterone receptor is of limited utility because it is often lost in anaplastic meningiomas.

Primary sarcomas of the dura may also pose challenges in differential diagnosis. Meningeal fibrosarcomas generally feature distinctive “herringbone” architecture, pericellular reticulin, and of course lack of EMA immunoreactivity. Nonetheless, so-called “sarcomatous meningiomas,” in actuality anaplastic meningiomas with predominance of mesenchymal metaplasia, may show no evidence of a residual meningothelial component or its immunophenotype.2 In such instances, a diagnosis of sarcoma may be inescapable.

[1] Cushing H., Eisennhardt L. Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behavior, Life History and Survival End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1938.

[2] Burger P.C., Scheithauer B.W. Meningiomas. In: Burger P.C., Scheithauer B.W., editors. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology, 2007.

[3] Burger P.C., Scheithauer B.W., Vogel F.S. Surgical Pathology of the Nervous System and its Coverings, 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

[4] Schiffer D. Brain Tumors. Biology, Pathology and Clinical References. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1997.

[5] Deen Jr H.G., Scheithauer B.W., Ebersold M.J. Clinical and pathological study of meningiomas of the first two decades of life. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:317.

[6] Perry A., Dehner L.P. Meningeal tumors of childhood and infancy. An update and literature review. Brain Pathol. 2003;13:386.

[7] Al-Mefty O., Topsakal C., Pravdenkova S., Sawyer J.R., Harrison M.J. Radiation-induced meningiomas: clinical, pathological, cytokinetic, and cytogenetic characteristics. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:1002.

[8] Joachim T., Ram Z., Rappaport Z.H., et al. Comparative analysis of the NF2, TP53, PTEN, KRAS, NRAS and HRAS genes in sporadic and radiation-induced human meningiomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:218.

[9] Sadetzki S., Flint-Richter P., Ben-Tal T., Nass D. Radiation-induced meningioma: a descriptive study of 253 cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1078.

[10] Salvati M., Caroli E., Brogna C., Orlando E.R., Delfini R. High-dose radiation-induced meningiomas. Report of five cases and critical review of the literature. Tumori. 2003;89:443.

[11] Starshak R.J. Radiation-induced meningioma in children: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:537.

[12] Evans D.G., Birch J.M., Ramsden R.T. Paediatric presentation of type 2 neurofibromatosis. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:496.

[13] Goldstein R.A., Jorden M.A., Harsh I.V. Meningiomas: Natural History, Diagnosis and Imaging. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

[14] Kuratsu J., Kochi M., Ushio Y. Incidence and clinical features of asymptomatic meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:766.

[15] DeAngelis L.M. Brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:114.

[16] Antinheimo J., Sankila R., Carpen O., Pukkala E., Sainio M., Jaaskelainen J. Population-based analysis of sporadic and type 2 neurofibromatosis-associated meningiomas and schwannomas. Neurology. 2000;54:71.

[17] Love S., Louis D.N., Ellison D.E. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. London: Hodder Arnold, 2008.

[18] Elster A.D., Challa V.R., Gilbert T.H., Richardson D.N., Contento J.C. Meningiomas: MR and histopathologic features. Radiology. 1989;170:857.

[19] Mahmood A., Caccamo D.V., Tomecek F.J., Malik G.M. A typical and malignant meningiomas: a clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:955.

[20] Tamiya T., Ono Y., Matsumoto K., Ohmoto T. Peritumoral brain edema in intracranial meningiomas: effects of radiological and histological factors. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1046.

[21] Ide M., Jimbo M., Yamamoto M., Umebara Y., Hagiwara S., Kubo O. MIB-1 staining index and peritumoral brain edema of meningiomas. Cancer. 1996;78:133.

[22] Nakamura M., Roser F., Bundschuh O., Vorkapic P., Samii M. Intraventricular meningiomas: a review of 16 cases with reference to the literature. Surg Neurol. 2003;59:491.

[23] Carlotti Jr C.G., Neder L., Colli B.O., et al. Clear cell meningioma of the fourth ventricle. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:131.

[24] Thompson L.D., Bouffard J.P., Sandberg G.D., Mena H. Primary ear and temporal bone meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 36 cases with a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:236.

[25] Thompson L.D., Gyure K.A. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:640.

[26] Suster S., Moran C.A. Unusual manifestations of metastatic tumors to the lungs. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1995;12(2):193.

[27] Gaffey M.J., Mills S.E., Askin F.B. Minute pulmonary meningothelial-like nodules. A clinicopathologic study of so-called minute pulmonary chemodectoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:167.

[28] Ionescu D., Sasatomi E., Aldeeb D., et al. Pulmonary meningothelial-like nodules. A genotypic comparison with meningiomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:207.

[29] Kepes J.J. Meningiomas. Biology, Pathology, and Differential Diagnosis. New York: Masson, 1982.

[30] Lantos P.L., Vandenberg S.R., Kleihues P. Tumours of the Nervous System. London: Arnold, 1996.

[31] Russell D.S., Rubinstein L.J. Pathology of Tumours of the Nervous System. London: Arnold, 1989.

[32] Louis D.N., Scheithauer B.W., Budka H. Meningiomas. In: Kleihues P., Cavanee W.K., editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Nervous System. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2000.

[33] Perry A., Louis D.N., Scheithauer B.W., Budka H., von Deimling A. Meningiomas. In: Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavanee W.K., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007:164-172.

[34] Maier H., Ofner D., Hittmair A., Kitz K., Budka H. Classic, atypical, and anaplastic meningioma: three histopathological subtypes of clinical relevance. J Neurosurg.. 1992;77:616.

[35] Perry A., Lusis E.A., Gutmann D.H. Meningothelial hyperplasia: a detailed clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and genetic study of 11 cases. Brain Pathol. 2005;15:109.

[36] Ng H.K., Poon W.S., Goh K., Chan M.S. Histopathology of post-embolized meningiomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1224.

[37] Paek S.H., Kim S.H., Chang K.H., et al. Microcystic meningiomas: radiological characteristics of 16 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:965.

[38] Nagashima G., Fujimoto T., Suzuki R., Asai J., Itokawa H., Noda M. Dural invasion of meningioma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2006;23(1):13.

[39] Tan W.L., Wong J.H., Liew D., Ng I.H. Aquaporin-4 is correlated with peri-tumoural oedema in meningiomas. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33(5 Suppl.):S87.

[40] Budka H. Hyaline inclusions (Pseudopsammoma bodies) in meningiomas: immunocytochemical demonstration of epithelial-like secretion of secretory component and immunoglobulins A and M. Acta Neuropathol. 1982;56:294.

[41] Buhl R., Hugo H.H., Mihajlovic Z., Mehdorn H.M. Secretory meningiomas: clinical and immunohistochemical observations. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:297.

[42] Kepes J.J. The fine structure of hyaline inclusions (pseudopsammoma bodies) in meningiomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1975;34:282.

[43] Probst-Cousin S., Villagran-Lillo R., Lahl R., Bergmann M., Schmid K.W., Gullotta F. Secretory meningioma: clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical findings in 31 cases. Cancer. 1997;79:2003.

[44] Tirakotai W., Mennel H.D., Celik I., Hellwig D., Bertalanffy H., Riegel T. Secretory meningioma: immunohistochemical findings and evaluation of mast cell infiltration. Neurosurg Rev. 2006;29:41.

[45] Louis D.N., Hamilton A.J., Sobel R.A., Ojemann R.G. Pseudopsammomatous meningioma with elevated serum carcinoembryonic antigen: a true secretory meningioma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:129.

[46] Horten B.C., Urich H., Stefoski D. Meningiomas with conspicuous plasma cell-lymphocytic components: a report of five cases. Cancer. 1979;43:258.

[47] Bruno M.C., Ginguene C., Santangelo M., et al. Lymphoplasmacyte rich meningioma. A case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Sci. 2004;48:117.

[48] Roncaroli F., Scheithauer B.W., Laeng R.H., Cenacchi G., Abell-Aleff P., Moschopulos M. Lipomatous meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 18 cases with special reference to the issue of metaplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:769.

[49] Caldarella A., Buccoliero A.M., Marini M., Taddei A., Mennonna P., Taddei G.L. Oncocytic meningioma: a case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:109.

[50] Midi A., Sav A., Belirgen M. Oncocytic meningioma exhibiting chordoid differentiation in its recurrence and histologic grading: case report (review of literature). J Neurol Sci (Turkish). 2005;22:428.

[51] Roncaroli F., Riccioni L., Cerati M., et al. Oncocytic meningioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:375.

[52] Robinson J.C., Challa V.R., Jones D.S., Kelly D.L.Jr. Pericytosis and edema generation: a unique clinicopathological variant of meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:700.

[53] Lalitha V.S., Rubinstein L.J. Reactive glioma in intracranial sarcoma: a form of mixed sarcoma and glioma (“sarcoglioma”): report of eight cases. Cancer. 1979;43(1):246.

[54] Izci Y., Secer H.I., Gönül E., Ongürü O. Simultaneously occurring vestibular schwannoma and meningioma in the cerebellopontine angle: case report and literature review. Clin Neuropathol. 2007;26(5):219.

[55] Alexander R.T., McLendon R.E., Cummings T.J. Meningioma with eosinophilic granular inclusions. Clin Neuropathol. 2004;23:292.

[56] Haberler C., Jarius C., Lang S., et al. Fibrous meningeal tumours with extensive non-calcifying collagenous whorls and glial fibrillary acidic protein expression: the whorling-sclerosing variant of meningioma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2002;28:42.

[57] Kim N.R., Im S.H., Chung C.K., Suh Y.L., Choe G., Chi J.G. Sclerosing meningioma: immunohistochemical analysis of five cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:126.

[58] Couce M.E., Perry A., Webb P., Kepes J.J., Scheithauer B.W. Fibrous meningioma with tyrosine-rich crystals. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1999;23:341.

[59] Litofsky N.S., Zee C.S., Breeze R.E., Chandrasoma P.T. Meningeal melanocytoma: diagnostic criteria for a rare lesion. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(5):945.

[60] Brat D.J., Giannini C., Scheithauer B.W., Burger P.C. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous systems. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(7):745.

[61] Nestor S.L., Perry A., Kurtkaya O., et al. Melanocytic colonization of a meningothelial meningioma: histopathological and ultrastructural findings with immunohistochemical and genetic correlation: case report. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:211.

[62] Cserni G., Bori R., Huszka E., Kiss A.C. Metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma in right sylvian secretory meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16:66.

[63] Elmaci L., Ekinci G., Kurtkaya O., Sav A., Pamir M.N. Tumor in tumor: metastasis of breast carcinoma to intracranial meningioma. Tumori. 2001;87:423.

[64] Watanabe T., Fujisawa H., Hasegawa M., et al. Metastasis of breast cancer to intracranial meningioma: case report. Am J Clin Oncol. 2002;25:414.

[65] Sonet A., Hustin J., De Coene B., et al. Unusual growth within a meningioma (leukemic infiltrate). Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:127.

[66] Perry A., Stafford S.L., Scheithauer B.W., Suman V.J., Lohse C.M. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1455.

[67] Jaaskelainen J., Haltia M., Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy, and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233.

[68] Couce M.E., Aker F.V., Scheithauer B.W. Chordoid meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:899.

[69] Heth J.A., Kirby P., Menezes A.H. Intraspinal familial clear cell meningioma in a mother and child. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:317.

[70] Jallo G.I., Kothbauer K.F., Silvera V.M., Epstein F.J. Intraspinal clear cell meningioma: diagnosis and management: report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:218.

[71] Zorludemir S., Scheithauer B.W., Hirose T., Van Houten C., Miller G., Meyer F.B. Clear cell meningioma. A clinicopathologic study of a potentially aggressive variant of meningioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:493.

[72] Oviedo A., Pang D., Zovickian J., Smith M. Clear cell meningioma: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8:386.

[73] Bannykh S.I., Perry A., Powell H.C., Hill A., Hansen L.A. Malignant rhabdoid meningioma arising in the setting of preexisting ganglioglioma: a diagnosis supported by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1450.

[74] Kepes J.J., Moral L.A., Wilkinson S.B., Abdullah A., Llena J.F. Rhabdoid transformation of tumor cells in meningiomas: a histologic indication of increased proliferative activity: report of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:231.

[75] Parwani A.V., Mikolaenko I., Eberhart C.G., Burger P.C., Rosenthal D.L., Ali S.Z. Rhabdoid meningioma: cytopathologic findings in cerebrospinal fluid. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;29:297.

[76] Perry A., Scheithauer B.W., Stafford S.L., Abell-Aleff P.C., Meyer F.B. Rhabdoid” meningioma: an aggressive variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1482.

[77] Perry A. Meningiomas. Russell and Rubinstein’s Pathology of Tumors of the Nervous System, 7th ed. Hodder Arnold, London, 2006.

[78] Perry A, Fuller CE, Judkins AR, Dehner LP, Biegel JA. INI1 expression is retained in composite rhabdoid tumors, including rhabdoid meningiomas. Mod Pathol 18(7):951.

[79] Kros J.M., Cella F., Bakker S.L., Paz Y.G.D., Egeler R.M. Papillary meningioma with pleural metastasis: case report and literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102:200.

[80] Ludwin S.K., Rubinstein L.J., Russell D.S. Papillary meningioma: a malignant variant of meningioma. Cancer. 1975;36:1363.

[81] Perry A., Scheithauer B.W., Stafford S.L., Lohse C.M., Wollan P.C. Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046.

[82] Perry A., Chicoine M.R., Filiput E., Miller J.P., Cross D.T. Clinicopathologic assessment and grading of embolized meningiomas: a correlative study of 64 patients. Cancer. 2001;92:701.

[83] Paulus W., Meixensberger J., Hofmann E., Roggendorf W. Effect of embolisation of meningioma on Ki-67 proliferation index. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:876.

[84] Patsouris E., Laas R., Hagel C., Stavrou D. Increased proliferative activity due to necroses induced by pre-operative embolization in benign meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 1998;40(3):257.

[85] Jaaskelainen J., Haltia M., Laasonen E., Wahlström T., Valtonen S. The growth rate of intracranial meningiomas and its relation to histology. An analysis of 43 patients. Surg Neurol. 1985;24(2):165.

[86] Maier H., Wanschitz J., Sedivy R., Rossler K., Ofner D., Budka H. Proliferation and DNA fragmentation in meningioma subtypes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1997;23:496.

[87] Nakasu S., Li D.H., Okabe H., Nakajima M., Matsuda M. Significance of MIB-1 staining indices in meningiomas: comparison of two counting methods. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:472.

[88] Perry A., Stafford S.L., Scheithauer B.W., Suman V.J., Lohse C.M. The prognostic significance of MIB-1, p53, and DNA flow cytometry in completely resected primary meningiomas. Cancer. 1998;82:2262.

[89] Abramovich C.M., Prayson R.A. Histopathologic features and MIB-1 labeling indices in recurrent and nonrecurrent meningiomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:793.

[90] Hsu D.W., Efird J.T., Hedley-Whyte E.T. MIB-1 (Ki-67) index and transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF alpha) immunoreactivity are significant prognostic predictors for meningiomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1998;24:441.

[91] Rezanko T., Akkalp A.K., Tunakan M., Sari A.A. MIB-1 counting methods in meningiomas and agreement among pathologists. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2008;30(1):47.

[92] Hsu D.W., Efird J.T., Hedley-Whyte E.T. Progesterone and estrogen receptors in meningiomas: prognostic considerations. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:113.

[93] Perry A., Cai D.X., Scheithauer B.W., et al. Merlin, DAL-1, and progesterone receptor expression in clinicopathologic subsets of meningioma: a correlative immunohistochemical study of 175 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:872.

[94] Arishima H., Sato K., Kubota T. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of gap junction proteins connexin26 and 43 in human arachnoid villi and meningeal tumors. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:1048.

[95] Miettinen M., Paetau A. Mapping of the keratin polypeptides in meningiomas of different types: an immunohistochemical analysis of 463 cases. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:590.

[96] Liu Y., Sturgis C.D., Bunker M., et al. Expression of cytokeratin by malignant meningiomas: diagnostic pitfall of cytokeratin to separate malignant meningiomas from metastatic carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1129.

[97] Hahn H.P., Bundock E.A., Hornick J.L. Immunohistochemical staining for claudin-1 can help distinguish meningiomas from histologic mimics. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:203.

[98] Hojo H., Abe M. Rhabdoid papillary meningioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:964.

[99] Su M., Ono K., Tanaka R., Takahashi H. An unusual meningioma variant with glial fibrillary acidic protein expression. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:499.

[100] Lamszus K., Lachenmayer L., Heinemann U., et al. Molecular genetic alterations on chromosomes 11 and 22 in ependymomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:803.

[101] Lamszus K., Vahldiek F., Mautner V.F., et al. Allelic losses in neurofibromatosis 2-associated meningiomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:504.

[102] Lamszus K. Meningioma pathology, genetics, and biology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:275.

[103] Perry A., Gutmann D.H., Reifenberger G. Molecular pathogenesis of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:183.

[104] Lekanne Deprez R.H., Riegman P.H., van Drunen E., et al. Cytogenetic, molecular genetic and pathological analyses in 126 meningiomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:224.

[105] Zang K.D. Meningioma: a cytogenetic model of a complex benign human tumor, including data on 394 karyotyped cases. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;93:207.

[106] Perry A., Banerjee R., Lohse C.M., Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K., Scheithauer B.W. A role for chromosome 9p21 deletions in the malignant progression of meningiomas and the prognosis of anaplastic meningiomas. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:183.

[107] Weber R.G., Bostrom J., Wolter M., et al. Analysis of genomic alterations in benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas: toward a genetic model of meningioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14719.

[108] Bostrom J., Meyer-Puttlitz B., Wolter M., et al. Alterations of the tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A (p16(INK4a)), p14(ARF), CDKN2B (p15(INK4b)), and CDKN2C (p18(INK4c)) in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:661.

[109] Al-Mefty O., Kadri P.A., Pravdenkova S., Sawyer J.R., Stangeby C., Husain M. Malignant progression in meningioma: documentation of a series and analysis of cytogenetic findings. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:210.

[110] Buschges R., Ichimura K., Weber R.G., Reifenberger G., Collins V.P. Allelic gain and amplification on the long arm of chromosome 17 in anaplastic meningiomas. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:145.

[111] Perry A., Jenkins R.B., Dahl R.J., Moertel C.A., Scheithauer B.W. Cytogenetic analysis of aggressive meningiomas: possible diagnostic and prognostic implications. Cancer. 1996;77:2567.

[112] Kolles H., Niedermayer I., Schmitt C., et al. Triple approach for diagnosis and grading of meningiomas: histology, morphometry of Ki-67/Feulgen stainings, and cytogenetics. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;137:174.

[113] Ozek M.M., Sav A., Pamir M.N., Ozer A.F., Ozek E., Erzen C. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma associated with von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 1993;9:39.

[114] Simon M., von Deimling A., Larson J.J., et al. Allelic losses on chromosomes 14, 10, and 1 in atypical and malignant meningiomas: a genetic model of meningioma progression. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4696.

[115] Korshunov A., Shishkina L., Golanov A. Immunohistochemical analysis of p16ink4a, p14arf, p18ink4c, p21cip1, p27kip1 and p73 expression in 271 meningiomas correlation with tumor grade and clinical outcome. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:728.

[116] Brandis A., Mirzai S., Tatagiba M., Walter G.F., Samii M., Ostertag H. Immunohistochemical detection of female sex hormone receptors in meningiomas: correlation with clinical and histological features. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:212.

[117] Perry A., Scheithauer B.W., Nascimento A.G. The immunophenotypic spectrum of meningeal hemangiopericytoma: a comparison with fibrous meningioma and solitary fibrous tumor of meninges. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1354.

[118] Cristi E., Perrone G., Battista C., Benedetti-Panici P., Rabitti C. A rare case of solitary fibrous tumour of the pre-sacral space: morphological and immunohistochemical features. In Vivo. 2005;19(4):777.

[119] Jung S.M., Kuo T.T. Immunoreactivity of CD10 and inhibin alpha in differentiating hemangioblastoma of central nervous system from metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(6):788.

[120] Weinbreck N., Marie B., Bressenot A., et al. Immunohistochemical markers to distinguish between hemangioblastoma and metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma in the brain: utility of aquaporin1 combined with cytokeratin AE1/AE3 immunostaining. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008. May 15