15 Neurology

Diplopia

Case history (1)

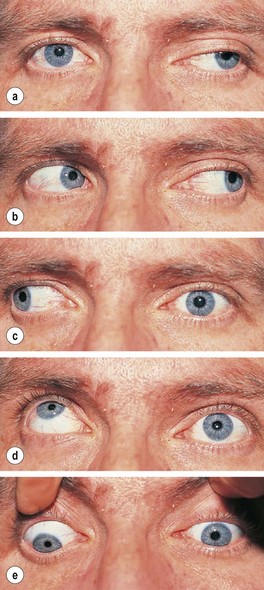

On examination there is ptosis in the left eye and the eye is deviated downwards and laterally (down and out) and fails to elevate or move medially (Fig. 15.1). The pupils both react normally. He is otherwise well. Random blood glucose is 11.5 mmol/L. HbA1c is 8% (64 mmol/mol).

What immediate action would you take?

• Achieve better diabetic control.

• Reassure that recovery is likely (but not definite) over weeks.

If no recovery, refer to a neurologist for MRI scan and investigation of causes of mononeuritis multiplex (see p. 471).

Information

• A painless third nerve palsy with preserved pupil reactions commonly occurs in the setting of diabetes due to nerve infarction.

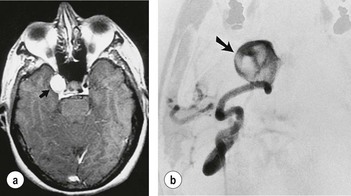

• If there is headache, especially of sudden onset, a posterior communicating artery aneurysm compressing the third nerve in front of the midbrain is a likely cause. Such a lesion also commonly involves the parasympathetic pupillary constricting fibres so that the pupil is fixed and dilated. MR angiography is indicated in this situation (Fig. 15.2).

What action would you take?

Confirm diagnosis of myasthenia by:

• Serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies (present in 40% of cases with eye involvement only with 100% specificity).

This patient was diagnosed as having myasthenia gravis and was referred urgently to a neurologist. Myasthenia gravis is sometimes restricted to the ocular system and can present as a variable gaze palsy that is difficult to interpret in terms of individual muscles or cranial nerves. There is not always a history of fatiguability. Some of the many causes of diplopia are listed in Table 15.1.

| Muscle/obstructive | Thyroid eye disease |

| Orbital masses | |

| Orbital pseudotumour (ocular myositis) | |

| Myasthenia | |

| Latent squint (visible when tired) | |

| Cranial nerves | Mass lesion in path of III, IV or VI nerves |

| Mononeuritis multiplex | |

| False localising due to raised intracranial pressure | |

| Central | Brainstem inflammation, demyelination, brainstem mass lesion, infarction, haemorrhage |

What action would you take?

In this case the ventricles were normal and therefore it was safe to proceed to a lumbar puncture. The opening pressure was recorded at 30 cm (normal pressure < 25 cm). A volume of CSF (usually around 20 mL) should be removed, so as to approximately halve the opening pressure.

Loss of vision

What is the differential diagnosis?

Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) are usually diagnosed clinically. Other causes of visual loss are shown in Table 15.2.

| Ophthalmological | Neurological |

|---|---|

| Glaucoma | Optic neuritis/demyelination |

| Amaurosis fugax | Compressive lesion of the optic nerve, chiasm, tract |

| Giant cell (temporal) arteritis | TIA/stroke of posterior cerebral circulation |

| Anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy | Migraine |

| Central retinal vessel occlusion | Occipital, temporal, parietal haemorrhage |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | Occipital, temporal, parietal space-occupying lesion |

| Retinal detachment | Temporal lobe epilepsy |

| Uveitis, keratitis | Raised intracranial pressure |

Remember giant cell arteritis, which causes acute visual loss. It responds to steroids (see p. 182).

Treatment

• Paracetamol 1 g, aspirin 900 mg (dispersible formulation) or an NSAID, e.g. ibuprofen 400–600 mg or naproxen 500 mg is given, as early as possible during an attack. Gastric emptying is reduced during the attack so dispersible formulations are preferred.

• Antiemetics (e.g. metoclopramide 10 mg or domperidone 10 mg).

• If these measures are ineffective, use a 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT)1B/1D serotonin receptor agonist (triptan). These drugs relieve both the pain and the nausea. Triptans should be avoided in patients with vascular disease or uncontrolled/severe hypertension. Triptans should be given at the onset of the headache (e.g. during the aura phase). There are several triptans available with a spectrum of efficacy, e.g.:

• If there is no response to an initial dose, do not persist with subsequent doses during the same attack. However, the drug may be effective in subsequent attacks.

Bell’s palsy

An acute VII nerve lesion, Bell’s palsy (Fig. 15.4) is usually due to a viral infection (often herpes simplex). It involves the VII facial nerve (motor only) with occasionally a loss of taste on the tongue and hyperacusis. There should be no sensory loss or other cranial nerve involvement.

Note:

• Sarcoidosis should be suspected in cases of bilateral Bell’s palsy.

• A rare condition causing bilateral Bell’s palsy and tongue swelling with other features is Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome.

• Progressive multiple cranial nerve palsies should lead to suspicion of malignant meningitis, or lymphomatous or carcinomatous infiltration.

Vertigo

What is the likely diagnosis?

Peripheral vestibular lesions are characterised by positional vertigo, i.e. influenced – often in a stereotyped way – by head movement. This is manifest in the Hallpike’s test (Information box; Fig. 15.5), which characteristically reveals a rotational nystagmus.

Main causes of vertigo

Stroke

Pathophysiology

What immediate action would you take in this case (i.e. cerebral infarct)?

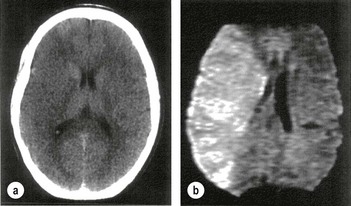

• Is thrombolysis to be considered? Yes. This stroke occurred less than 180 min ago, therefore immediate diffuse weighted MRI (more sensitive than CT) if available should be performed (Fig. 15.6). Unfortunately it was not available for this patient.

• CT will distinguish haemorrhage immediately but infarction cannot be seen early on (Fig. 15.6a).

In this patient the CT showed no evidence of haemorrhage, therefore cerebral infarction was likely.

Other immediate action

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

• anterior circulation – sudden transient loss of vision in one eye (amaurosis fugax), aphasia, hemiparesis; or

• posterior circulation – diplopia, ataxia, hemisensory loss, dysarthria, transient global amnesia.

TIAs may herald the onset of stroke (one-quarter of patients developing stroke have had a TIA, usually within the previous week).

The ABCD2 score can help to stratify stroke risk in the first 2 days.

| • Age > 60 years | 1 point |

| • BP > 140 mmHg systolic and/or > 90 mmHg diastolic | 1 point |

| • Clinical features: | |

| Unilateral weakness | 2 points |

| Isolated speech disturbance | 1 point |

| Other | 0 points |

| • Duration of symptoms (min) | |

| > 60 | 2 points |

| 10–59 | 1 point |

| < 10 | 0 points |

| • Diabetes | |

| Present | 1 point |

| Absent | 0 points |

A score of < 4 is associated with a minimal risk, whereas > 6 is high risk for a stroke within 7 days of a TIA.

• If patients are at a high risk of a TIA, i.e. ABCD2 score > 4, or have had two recent TIAs, especially within the same vascular territory, they should be admitted for investigation and treatment (see below).

• All patients should be referred to a TIA clinic and ideally seen within 24 hours. Investigation and treatment should be regarded as urgent and should be completed within 10 days.

Treatment

• Antiplatelet therapy as for stroke (p. 477).

• Modification of vascular risk factors – smoking, hypertension, statins as above.

• Early endarterectomy for symptomatic 70–99% carotid artery stenosis (within 1 week if possible).

• Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (p. 274) (aspirin 300 mg daily for 2 weeks, then anticoagulate with heparin and warfarin or dabigatran) (see p. 276).

Brott G, Hobson RW 2nd, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23.

Rothwell PM, Algra A, Amarenco P. Medical treatment in acute and long-term secondary prevention after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 2011;377:1681–1692.

Subdural haemorrhage

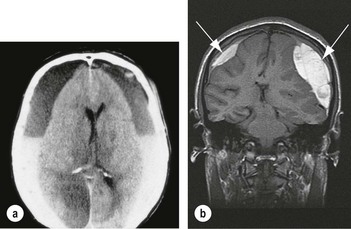

On examination, she was confused, unable to repeat a five-digit number, disorientated and had an upgoing left plantar. Her Glasgow Coma Score (GCS, p. 492) was 12.

Parkinson’s disease

What is the problem?

Other treatment available

• Exercise and physiotherapy are useful.

• Initiate pharmacological treatment when there is impairment/disability resulting from symptoms.

• Early treatment with monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) inhibitors (selegiline or rasagiline) may delay the need for more definitive dopamine replacement therapy by several months.

• Dopamine agonists (DAs) are used in patients below 70 years. Although they are less effective and less well tolerated than LD, they are also associated with fewer long-term motor complications.

• In older patients (i.e. more severely affected at diagnosis) start LD + DDI (co-beneldopa or co-careldopa) because of fewer side effects.

• Non-ergot DAs (pramipexole and ropinirole oral 3 times daily, or once daily with slow-release formulations, rotigotine via transdermal patch) are used in preference to ergot-derived drugs.

• All patients with PD will eventually require treatment with LD, often in combination with a DA. A typical starting dose is 50 mg of LD (e.g. co-careldopa 62.5 mg) 3 times daily, increasing after 1 week to 100 mg 3 times daily.

Multiple sclerosis (MS)

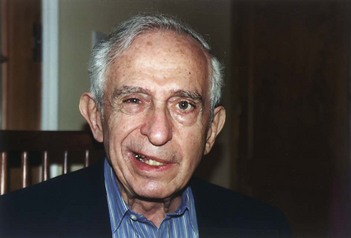

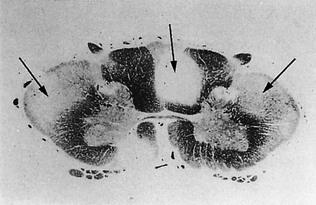

MS is an autoimmune disease of unknown aetiology. It causes plaques of demyelination throughout the brain and spinal cord. Acute relapses are caused by focal inflammatory demyelination which causes a conduction block. These plaques can be demonstrated using an MRI scan (Fig. 15.8).

Figure 15.8 Multiple sclerosis – showing plaques in the posterior column and lateral corticospinal tracts.

(Courtesy of the late Ian MacDonald).

Case history (1)

A 28-year-old man presents with several days of pain and progressive loss of vision in one eye.

What action would you take?

• An MRI should be performed to look for demyelinating lesions of MS.

• CSF analysis for oligoclonal bands is usually unnecessary to further corroborate the diagnosis.

• Visual evoked potentials are likely to be delayed in the affected eye but may also reveal subclinical involvement of the other eye, providing evidence for dissociation in space.

• Medication. Recovery after an episode of optic neuritis is aided by intravenous methylprednisolone, e.g. 1 g/day for 3 days.

What would you suggest?

Many forms of treatment have been marketed, but none has been shown to improve outcome.

• Acute relapses. Short courses of steroids, such as IV methylprednisolone 1g/day for 3 days or high-dose oral steroids, are used widely in relapses and do sometimes reduce severity. They do not influence long-term outcome.

• Preventing relapse and disability. Beta-interferon (both INF β-1b and β-1a) by self-administered injection is used in relapsing and remitting disease. This is defined as at least two attacks of neurological dysfunction over the previous 2 or 3 years followed by a reasonable recovery. IFN β1b is also used for secondary progressive MS. Interferon certainly reduces relapse rate in some patients and prevents an increase in lesions seen on MRI. Unwanted effects are flu-like symptoms and irritation at injection sites. Beta-interferons are expensive.

• Glatiramer acetate, an immunomodulator, has been shown to reduce relapse frequency in ambulatory patients with relapsing remitting MS – similar to beta-interferon.

• Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody which inhibits migration of leucocytes into the central nervous system by inhibitory α-4 integrins found on the surface of lymphocytes and monocytes. It is useful in severe, relapsing remitting MS that is unresponsive to other treatments. It is associated with a risk of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) and all patients need close surveillance for this and hypersensitivity reactions.

• Alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody that destroys T- and B-cells, reduces disease activity.

• Mitoxantrone is used in primary progressive MS in specialist centres. It is potentially cardiotoxic and myelosuppressive.

• New oral disease modifying drugs, e.g. fingolimod, a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator, and cladribine (both given orally), an immunomodulator of lymphocytes, have shown benefit in ongoing trials.

Encephalitis

This is an inflammation of the brain parenchyma which is often due to a virus.

What action would you take?

• Supportive care: including respiratory support if necessary.

• Treatment of any seizures: ictal and post-ictal states are a reversible element of changes in conscious level.

• CT scan showed no space-occupying lesion.

• Lumbar puncture: there was a lymphocytosis.

• Serology and PCR: for likely aetiological agents (see below).

• If there is even a remote possibility that the cause is HSV1, start aciclovir immediately, intravenous 10 mg/kg × 3 daily. HSV is treatable; most other causes are not (Box 15.1). Patients have been known to relapse and respond to further treatment.

Box 15.1

Causes of encephalitis/meningoencephalitis

In immunocompromised people think of unusual organisms, e.g. fungal.

Remember

• Most cases of viral encephalitis present in the same way, the symptoms being milder than those for a bacterial meningitis. In many cases the viral cause can be worked out from the epidemiological pattern, e.g. from the geographical area where the disease was contracted and the season of the year.

• The term ‘encephalitis’ encompasses any acute febrile illness, perhaps with some meningeal involvement, that is accompanied by acute generalised or focal cerebral disturbance. Thus there is considerable overlap with meningitis.

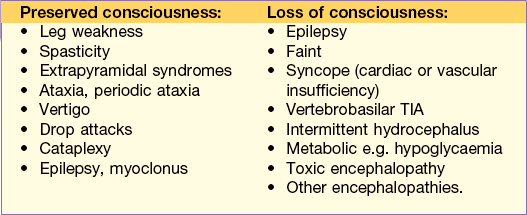

Falls

What is the diagnosis?

Some common causes of falls are listed below. Some simply relate to stance or gait difficulties.

What is the diagnosis?

The diagnosis is drop attacks. These are benign episodes that commonly occur in middle-aged to elderly women. There is no loss of consciousness and they are not considered epileptic (see p. 503). They are due to sudden changes in lower limb tone, presumably brainstem in origin.

Traumatic brain injury

Case history (1)

A 25-year-old man is knocked unconscious by a blow from a sledgehammer. He regains consciousness after a few minutes and attends A&E. He is nauseated and in pain but reasonably alert, with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; Table 15.3) of 14. A skull X-ray shows a linear skull vault fracture. After being reasonably well for many hours his conscious level rapidly deteriorates to a GCS of 5. A subsequent CT scan reveals a large extradural blood collection that requires emergency drainage by craniotomy.

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Eye opening (E) | |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| Motor response (M) | |

| Obeys | 6 |

| Localises | 5 |

| Withdraws | 4 |

| Flexion | 3 |

| Extension | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

| Verbal response (V) | |

| Orientated | 5 |

| Confused conversation | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| No response | 1 |

Glasgow Coma Scale = E + M + V (GCS minimum = 3; maximum = 15)

General management of traumatic injuries

Remember

• Always carefully monitor head injuries and record changes in GCS rather than simply considering one value in isolation

• The result of secondary swelling by haemorrhage or oedema (the latter is common in children) is raised intracranial pressure (ICP) leading to reduced perfusion pressure and coning.

What action would you take in a patient with a head injury?

• Attend first to any secondary or concomitant general problems, i.e. resuscitation, correct hypovolaemic shock, hypotension or compromised airway.

• Assess severity, using circumstances of injury and period of amnesia as a guide.

• Establish whether there is anterograde amnesia: the inability to form memories from the time of injury to the time of continuous normal memory, is the most accurate guide.

• Brainstem damage in head injury can affect central respiratory drive, bulbar function and pressor responses.

• Regular GCS measurements; below 5 at 24 h implies severe injury and 50% of such patients die.

Box 15.2

NICE Guidelines for head injuries

Criteria for immediate request for CT scan of the head (adults)

• GCS less than 13 on initial assessment in the emergency department

• GCS less than 15 at 2 hours after injury on assessment in the emergency department

• Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

• Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanium, ‘panda’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid leakage from the ear or nose, Battle’s sign)

How would you manage the following problems?

• If the patient is deteriorating, or has evidence of raised ICP: consider insertion of a bolt, which is simply a tube into the ventricle through which ICP can be recorded.

• If ICP > 20 mmHg: need to treat; give enough mannitol IV to raise the plasma osmolality to 300 to decrease the intracranial pressure. However, the benefits of mannitol are still controversial. Mannitol also has poorly understood neuroprotective effects. Hyperventilation with IPPV will also lower the ICP.

• If the patient has haemorrhages: a craniotomy may be indicated.

Severe brain injury

What action would you take?

First, check for a remediable cause of coma or any confounding factors worsening the patient’s responsiveness (see Investigations box). For example:

• Brain imaging may reveal a potentially treatable but unsuspected condition, possibly additional to the primary pathology, such as subdural or intracerebral haemorrhage or a hydrocephalus.

• An EEG may show abnormalities indicative of an unsuspected metabolic encephalopathy or subclinical seizure activity.

• The patient may still be under the influence of long-acting anaesthetic agents or other sedative drugs.

Aspects of examination to assess routinely

What are your prognostic indicators?

• Absent or extensor plantar response 72 hours after cerebral insult.

• Absent pupillary or corneal reflexes 72 hours after cerebral insult.

In general, every case must be assessed on its merits, especially with regard to the nature of the original insult and whether it was a discrete event or likely to be resulting in ongoing brain injury.

Note: relatives should not be given conflicting or inaccurate information.

Beware

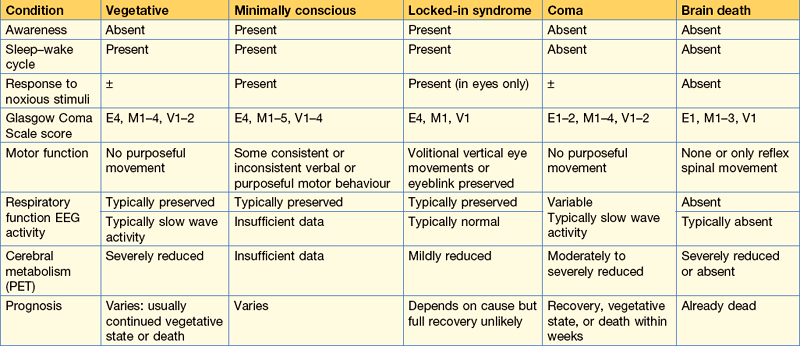

Determination of brain death is made only by the appropriate consultant specialists who assess – on separate occasions – the various brainstem reflexes and responses listed under ‘Aspects of examination’, above. The nature of the insult must be clear and remediable causes must be excluded. Because the criteria for brain death are heavily weighted towards brainstem function and, in the UK, EEG corroboration is not required, the locked-in syndrome (Table 15.4) should be excluded. In this state, a severe pontine lesion prevents access to or from the outside world. The only signs of relatively spared higher-level function may be preserved vertical optokinetic nystagmus or eye following, and preserved vertical doll’s eye reflexes.

Table 15.4 Differentiation diagnosis of the vegetative state

From: The vegetative state: guidance on diagnosis and management. Clinical Medicine 2003; 3: 251.

Meningitis

Case history (1)

A 55-year-old, a heavy alcohol user is brought to A&E with headache, confusion and a high fever.

What do you do next?

Information

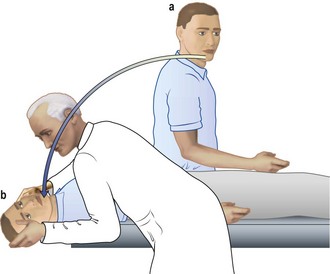

Lumbar puncture

This should be performed with sterile measures. Check no papilloedema:

• Place patient in lateral decubitus position

• Identify L4–5 interspace (intersection of imaginary line between iliac crests and spine)

• Clean area with antiseptic, e.g. chlorhexidine

• Local anaesthetic (2% lidocaine) into skin and subcutaneous tissue

• Insert lumbar puncture spinal needle (bevel upwards) into skin over L4–5 interspace horizontally and slightly towards the head

• When needle penetrates the dura mater (slight decrease in resistance is felt), withdraw stylet and allow a few drops of CSF to escape

• Measure CSF pressure by connecting manometer to needle (normal CSF pressure is 60–150 mmH2O); it rises and falls with respiration and heart beat

• Collect CSF in three sterile tubes (2 mL per tube)

• Send to laboratory. Note if clear, cloudy, yellow (xanthochromic) or red

• Remove needle and apply sterile dressing

• Patient should lie horizontal for 4 h to avoid headache. Analgesics might be required.

Indications and contraindications are shown in Table 15.5.

Table 15.5 Indications and contraindications for lumbar puncture

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis of meningitis, encephalitis and subarachnoid haemorrhage (sometimes) | Raised intracranial pressure |

| Measurement of CSF pressure, e.g. for idiopathic, intracranial hypertension (IIH) | Local infections at site of puncture area |

| Removal of CSF therapeutically (IIH) | Platelet count < 40 × 109/L |

| Diagnosis of conditions, e.g. neoplastic involvement | Mass lesion in brain or spinal cord |

Diagnosis

Pneumococcal meningitis. You immediately start treatment with IV cefotaxime 8 g daily in four divided doses because there is a high incidence of penicillin-resistant pneumococcus (Table 15.6).

Table 15.6 Treatment regimens: antibiotics and acute bacterial meningitis

| Organism | First choice | Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown | Cefotaxime | Benzylpenicillin and cefotaxime |

| Meningococcus | Benzylpenicillin | Cefotaxime |

| Pneumococcus | Cefotaxime | Penicillin if organism sensitive |

| Haemophilus | Cefotaxime | Chloramphenicol |

| Listeria | Amoxicillin + gentamicin |

This table shows the value of cefotaxime in clinical practice.

Causes of meningitis

• Pneumococcal meningitis most commonly occurs in the debilitated or in those with a chest or sinus infection, valvular disease, splenectomy or a fistula from the paranasal air sinuses to the brain.

• Meningococcal meningitis (see also p. 7) occurs in epidemics and is sometimes associated with a petechial or purpuric rash and has a very rapid evolution. It is seen in young adults. Nasopharyngeal swab culture is useful for typing meningococcus and haemophilus (see below).

• Staphylococcus aureus meningitis generally occurs in the context of systemic infection, abscesses or neurosurgical procedures.

• Pseudomonas and other Gram-negative enterobacillae are usually a consequence of surgical access to the CSF.

• Listeria meningitis is quite common. It should be treated with amoxicillin and gentamicin. It is also associated with an encephalitis.

• Haemophilus influenzae type B used to be extremely common but has been substantially reduced in many countries by immunisation (Hib vaccine) in children.

What action would you take?

• CXR: may show evidence of TB.

• CT scan: an immediate scan is done because with his confusion and possible raised intracranial pressure coning is a possibility following lumbar puncture. CT scan normal.

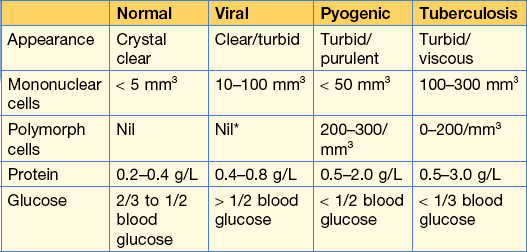

The CSF results (Table 15.7) sent back to your house officer are:

Note: the CSF protein can be so high as to cause the formation of a fine clot (‘spider web’).

Table 15.7 Typical changes in the CSF in meningitis

* Some polymorph cells may be seen in the early stages of viral meningitis and encephalitis.

Reprinted from Kumar and Clark Clinical Medicine 8th edn, 2012, by permission of the publisher Elsevier.

Fits and faints

Is this a fit or a faint?

The patient has probably suffered a faint. Some factors are good at distinguishing a fit from faint (Table 15.8) whereas others are unreliable. In the above case, it is noted that faints, other than cardiac syncope, only occur on standing; the preceding symptoms are prolonged or ill defined. Twitching is not usually as violent as in a clonic seizure and the underlying muscle tone is not increased.

| Fit | Faint | |

|---|---|---|

| Prodrome | None or characteristic brief aura | Short or prolonged. Blood draining, visual darkening, rushing noise. Cardiac syncope may have no prodrome |

| Posture at onset | Any | Standing unless cardiac |

| Injury | Common | Rarer. Protective reflexes may act |

| Incontinence | Sometimes | Sometimes |

| Skin colour | Normal, flushed or pale | Pale |

| Recovery | Slow return of consciousness | Rapid, more physical weakness with clear sensorium |

| Frequency | Rare to many a day | Not repeated attacks each day |

| EEG | May be abnormal | Normal |

Vasovagal faints are generally idiopathic but there are often precipitating or predisposing factors.

Associations with faints

Vasovagal attacks must be distinguished from cardiac syncope (see p. 265). In the latter there is often no warning, there may be breathlessness and engorged jugular veins and the heart rate may be faster than 140 or slower than 40.

How would you manage this situation?

Remember

Status epilepticus exists when seizures follow each other without recovery of consciousness.

General measures

• Secure the airway; remove any false teeth and insert oropharyngeal tube.

• Secure venous access: many anti-convulsants cause phlebitis, so choose a large vein.

• Glucose, 50 mL of 20% IV if hypoglycaemia is a possibility (see p. 221).

• Thiamine, 250 mg by slow IV injection if patient is a chronic alcohol user.

Control seizures

• Lorazepam 0.1 mg/kg by slow (2 mg/min) intravenous injection. Give rectal diazepam (10–20 mg) or intramuscular midazolam (0.2 mg/kg) if intravenous access difficult.

If seizures continue (despite phenytoin) use:

• Phenobarbital: 15 mg/kg at a rate not exceeding 100 mg/min and repeated at intervals of 6–8 h if necessary; IV clonazepam can also be used.

• If seizures continue despite these measures the patient is given a general anaesthetic, using thiopentone or propofol, and management is continued with full anaesthetic support.

Difficulty walking

What is the diagnosis?

Cervical myelopathy, which at this age is most commonly due to spondylitis. She requires an urgent MRI scan of her cervical spine with a view to early decompression because relatively acute deficits are more potentially reversible. The MRI showed cord compression at the level of C5–6 (Fig. 15.9).

Headaches

Case history (1)

A CT scan shows blood in the subarachnoid space (this has a 95% sensitivity in the first 24 hours).

Diagnosis.

• Arrange for cerebral MR angiography to identify the source of bleeding.

• If aneurysm found, refer to neurosurgeon for surgical treatment.

• Nimodipine (e.g. 60 mg orally 4-hourly for 2–3 weeks, or 1 mg/hour IV) can reduce arterial spasm and reduce further cerebral infarction.

• Avoid hypotension (it may worsen the ischaemic deficit). Treat hypertension if diastolic pressure is persistently > 130 mmHg. Aim for a very gradual decrease in BP with careful monitoring and frequent repeat neurological examination.

• Supportive measures include bed rest, analgesia and laxatives (avoid sudden rises in ICP or BP).

• Watch for complications, including hyponatraemia (SIADH), hydrocephalus (obstruction of cerebral aqueduct by blood) and vasospasm causing ischaemic deficits.

NB. If the scan is negative and the history highly suggestive of a subarachnoid haemorrhage, a lumbar puncture is necessary.

• A lumbar puncture is performed to look for blood-stained CSF and xanthochromia (bilirubin discoloration of CSF due to cell lysis). Xanthochromia may be detected from ~12 hours to 3 weeks after SAH. Visible inspection of a centrifuged sample is often sufficient to detect xanthochromia, but laboratory spectrophotometry is more sensitive.

Management

Broadly similar for episodic migraine, i.e. sumatriptan prophylaxis is given if the sufferer has more than about two migraines a month or finds them very debilitating. A migraine prophylactic agent should be given (see p. 470).

Movement disorders

Both may co-exist.

Guillain–Barré syndrome

How would you manage this patient?

• Regularly monitor her respiratory function with vital capacity. Intubation and ventilation might be required. Call for expert help.

• Nursing care: to avoid pressure ulcers.

• Prophylaxis: to prevent venous thrombosis (LMW heparin, enoxaparin).

• Steroid therapy is ineffective.

• IV immunoglobin given in the first 2 weeks reduces duration and severity of weakness. NB. Check IgA levels; severe allergic reactions occur (due to IgG antibodies) with IgA deficiency.

Spinal cord compression

NB. This is a medical emergency.

This patient has a mild paraparesis and a cord lesion must be exluded.

Investigations

• Routine bloods show a Hb of 100 g/L with an ESR of 100 mm/h.

• CXR was normal, making carcinoma with secondaries unlikely despite him being a heavy smoker.

• Thoracic and lumbar spinal X-rays showed an osteolytic lesion at T10.

The preliminary tests have taken 3 days and the patient is now incontinent of urine and his leg weakness is worse. Urgent neurological referral is required.