27 Neurological Symptoms

We have scotch’d the snake, not kill’d it.

She’ll close and be herself, whilst our poor malice Remains in danger of her former tooth.

Neurological symptoms present particular difficulties for those working in pediatric palliative medicine. The evidence base for most symptom interventions derives largely from work done in adults. Historically, adult palliative medicine has largely addressed the needs of patients with cancer, while it is in the large group of children with non-cancer conditions that neurological symptoms occur most commonly.1 Typically, they are neurodegenerative conditions in which deterioration to death occurs over years or decades, and are characterized by severe neurological symptoms that may be difficult to treat.

General Principles

Multidimensional

In considering the impact of neurological symptoms, professionals need to consider not only their physical effects, but also their influence on psychosocial, emotional, and spiritual issues. In focusing on reducing the frequency of seizures, for example, professionals should not lose sight of the need to allow a child to engage meaningfully with his or her family. This can lead to the involvement of a potentially large and extended team with varying but, at times, over-lapping roles (Box 27-1).

BOX 27-1 The Interdisciplinary Team

Rational

In establishing that a given intervention is in the child’s best interest, it is clearly necessary to be aware of the existing evidence. In an age where evidence-based medicine is a professional requirement,2 it is important that practice is not just based on anecdotes and experience, but also is justified with research. Critical appraisal and clinical reasoning must underpin practice. Systematic reviews or meta-analyses, where they exist, are authoritative sources of such evidence. Individual carefully designed double-blind trials are also powerful evidence. Anecdote and case history, however, are not indicators of effectiveness. They are important signposts to studies that should take place, but should not result in an uncritical change of practice by themselves.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) ap- proaches should be used in conjunction with conventional medicine to aim to provide better symptom control and meet the cultural, spiritual, and psychosocial needs of the child and family.3 Many neurological symptoms are exacerbated by depression, anxiety, and/or fatigue. There is evidence to suggest these are ameliorated by some CAM approaches, including massage,4–12 acupuncture,8,10,13–16 and transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS)8,17 can offer some assistance with this. The effectiveness of TENS is unclear18,19 but it is well tolerated by most patients. Music therapy and hydrotherapy are naturally enjoyable interventions for children (Fig. 27-1).

Symptoms

For a summary of doses and indications of medications in this chapter, see Table 27-1.

TABLE 27-1 Doses and Indications for Medications Mentioned in This Chapter

| Medication | Indication | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | Status epilepticus and terminal seizure control. Breakthrough anxiety, such as panic attacks. Adjuvant for pain of cerebral irritation. Dyspnea |

Seizures

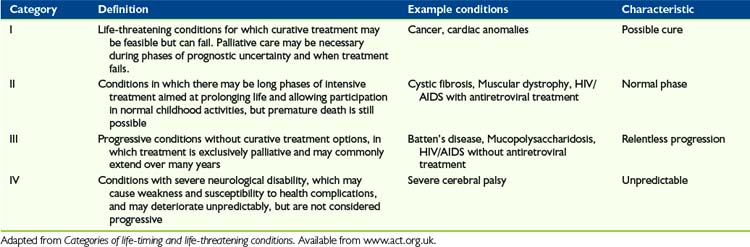

Children with life-limiting conditions in ACT categories III and IV (Table 27-2), which are often chronic neurological conditions, are likely to have seizures that have been difficult to control for some time. The result is typically that, at the time it is clear a palliative phase has been entered, children are on a large number of different anticonvulsants.

The solution to this is to use the buccal route. Small volumes of water soluble drugs such as midazolam and diamorphine can be administered between the cheek and the gum. They are absorbed rapidly through the oral mucosa, effectively providing an alternative parenteral route without needles. This is increasingly used for management of breakthrough seizures in neurology20 and is ideally suited to their management in the terminal phase.

Phenobarbital is rarely used in seizure disorders because of the risk of adverse effect in long-term use. In the palliative phase, however, where these are unlikely to be a significant consideration, it has a number of potential advantages over many other anticonvulsants, though not all are proved. It is anxiolytic, rather than simply sedative,21 effective against cerebral irritation; is sedating it may have some activity against neuropathic pain.22 It can also be given orally or through a gastrostomy tube.

It does, however, also have some disadvantages:

Midazolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine. It is often used by neurologists for breakthrough seizures, but rarely for background control because of its short half-life. In the palliative phase, Midazolam is usually given by continuous subcutaneous infusion although there is no reason in principle why it should not also be given intravenously. It can be mixed with other medications in the same syringe driver, including diamorphine, morphine, levomepromazine, and other medications commonly used in the final days of life. It is easy to titrate against symptoms due to its short half-life; 23 powerfully anxiolytic, amnestic and sedating; and has a broad range of anticonvulsant activity. Midazolam is widely used in pediatric palliative care, so it has reasonable clinical experience and evidence base. Also, it is highly soluble so can be given by buccal route.

Midazolam’s disadvantages are that paradoxical agitation can occur in some children24 and its short half-life makes it inappropriate for background control of seizures except by parenteral infusion. The drug can cause confusion; and in cognitively aware children, loss of memory may be a disadvantage, particularly if it impairs family relationships.

Non-Seizure Movements

Many children with abnormal movement patterns due to any neurological condition, palliative or not, have developed ways in which to use the fluctuations in muscle tone to enable them to carry out functional activities, such as walking. The aim, particularly in the palliative phase when these movements are likely to be increasing in amount and severity, should be to minimize the negative effects but optimize function to enable the child to manage desired activities (Box 27-2).

BOX 27-2 Movement Disorders

Dystonia

Dystonia is characterized by repetitive and sustained contraction of the muscles, leading to abnormal posture. It can result from the underlying condition, or from medications used in its treatment. Prolonged dystonia is referred to as status dystonicus.26

Drug-induced dystonias are associated with drugs that block dopamine receptors. These particularly include pure dopamine antagonists such as haloperidol and dopamine. The actual incidence of dystonic reactions with these medications is small, but more likely in pediatric than in adult practice.27 The medications are relatively frequently used in the palliative phase, however, and are important causes. Dystonic reactions caused by medication can be reduced or even avoided by the use of anticholinergics such as procyclidine or antihistamines such as diphenhydramine.

Conditions causing dystonia in the absence of medication include many of the metabolic disorders, particularly meta-chromatic leukodystrophy, the gangliosidoses and mitochondrial disorders. Deep brain stimulation,28 in which electrodes are placed in the globus pallidus area of the brain, is effective in such primary dystonias in children. This should be combined26 with attention to hypertonia.

Myoclonus

Myoclonus describes jerking interactions of a muscle or muscle group. They are typically brief, abrupt, and involuntary.29

Chorea

Chorea can be seen as intermediate in duration between myoclonus and dystonia.29 Like them, it is brief and purposeless and can seem to flow from limb to limb, called choreoathetosis.

Hyper- and hypotonia

Pharmacological Interventions

A number of interventions can reduce muscle tone.30

Baclofen can be given orally, but in some children its effect on truncal muscle tone is more marked than in the limbs, impairing posture so that the net impact can be adverse. The effectiveness of intrathecal baclofen in generalized hypertonia of cerebral palsy,31 particularly using a surgically implanted pump, is such that it is a useful modality despite its complications.32 A risk of accelerating the progression of scoliosis has been suggested,33,34 but remains unproved.35 Baclofen may have an additional effect as an adjuvant in neuropathic pain.36,37

Botulinum toxin38 binds irreversibly to the motor endplate, causing paralysis of a muscle unit until the endplate is re-synthesised. The safety profile is good.39

Cerebral irritation

The clinical causes and features of cerebral irritation should be distinguished from those of central thalamic pain (Table 27-3), a specific example of neuropathic pain (see Chapter 31) caused by damage to the pain-perceiving part of the brain. However, in practice the two may co-exist in a child unable to communicate his or her experience. It is often necessary to treat both simultaneously.

TABLE 27-3 Distinction Between Central, or Thalamic, Pain and Cerebral Irritation

| The distinction may not always be possible in clinical practice, and both may need to be treated in a single patient. |

| Central Pain | Cerebral Irritation | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathophysiology | Thalamic damage | Meningeal inflammation/infiltration/stretch |

| Causes | Cerebral vascular accident, tumor, probably metabolic conditions | Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, post-infection, post-trauma, leptomeningeal spread of malignancy |

| Type of pain | Neuropathic | Nociceptive |

| Chronicity | Often chronic, may be permanent | Follow acute injury, usually self-limiting over months |

| Characteristics | Difficult to pinpoint, all over body, often dysaesthesia | Abnormal processing, exaggerated startle, amplification of pain by unfocused anxiety, difficult to pinpoint |

| Pharmacological treatments | Antineuropathic agents (amitriptyline, anticonvulsants) | Aimed at reducing neuronal firing, anxiety and pain (phenobarbitone, benzos and opioids) |

Pharmacological Management

Management of cerebral irritation in the neonate requires a three-pronged attack:

Sleep-wake cycle

In ACT groups III and IV particularly, disruption of normal brain function is the rule. It is perhaps unsurprising that in this group disruption of the sleep-wake cycle is common.43,44 Its impact on the family can be profound. Endless nights of broken sleep inevitably accumulate and contribute to the global exhaustion reported by many families.45

One chemical mediator of the normal diurnal rhythm is melatonin, synthesized in the pineal gland and in T-lymphocytes.46 Exogenous melatonin is now available for oral use, and this can be a helpful intervention.44 The fact that it is not universally effective underlines the fact that disruption of the sleep-wake cycle is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon rather than simply a function of melatonin deficiency.

Non-Pharmacological Management

Sleep is often disturbed by anxiety, pain, depression, and other symptoms.48 It is important to ensure that these have been addressed as much as possible, even in the pre- or non-verbal child. There is evidence from the adult palliative care research that aromatherapy and massage can help to promote better sleep patterns.11 It is feasible that this may also be the case within the pediatric population.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms experienced by children with cancer.49 (See Chapter 29.) Furthermore, it is an obvious complication of many of the conditions in ACT/RCPCH Group II, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Despite this, the symptom of fatigue has received little attention in the pediatric literature. Even in adult palliative medicine, there is no single agreed-upon therapeutic approach. It is a multifactorial phenomenon, caused not only by the disease and the body’s defenses against it, but also therapeutic interventions themselves.

Fatigue is described as one of the symptoms that causes most distress49–54 and has received some attention in the adult cancer literature.55 Despite its apparent high prevalence in children with life-threatening conditions,49,51,52 it is relatively under-recognized in children,56 perhaps because it is difficult to diagnose and assess, and there are few effective interventions.

Fatigue, like all symptoms, is multidimensional,56 including symptoms directly arising from the underlying condition, and those arising from its treatment. These include:

Diagnosis and appropriate treatment of depression or anxiety is important. Guidelines58 suggest that management of depression in children should be undertaken in collaboration with child mental health services if possible. Correction of an altered sleep pattern should be attempted as much as possible.

There is some literature in adults suggesting that pharmacological stimulants can improve fatigue.59–61 In young people, this evidence is limited to reduction of opioid-induced drowsiness.62 Although the evidence base is weak, methylphenidate is familiar to most pediatricians and its safe use in children has been established, albeit in a different therapeutic context. In the absence of approaches supported by better evidence, it seems a reasonable therapeutic trial where fatigue is identified as a significant problem.

Non-Pharmacological Management

The main approach for rehabilitating a patient suffering fatigue uses paced exercise programs.63 For those children and families who are still able and wanting to participate in active rehabilitation, a graded, functional exercise program should be designed and implemented. For those unable or not wanting to take part in this, physical activity should be encouraged in a way and to a level that is appropriate and acceptable to the child and family. Again, this should be functionally aimed, enabling the child to participate in activities that he or she enjoys. A fine balance in the amount and frequency of activity should be found to ensure that the fatigue-reducing physiological benefits of physical activity are experienced without the child overdoing it and becoming exhausted. ”Little and often” is a useful adage to follow.

Studies of CAM approaches in the treatment of palliative adult cancer patients with fatigue4,7,17,64,65 suggest that massage, homeopathy, TENS, acupuncture, and even Reiki had a positive effect on participants’ perception of fatigue. There are far fewer studies in children, and all are in cancer.9,66 These suggest that massage measurably reduced anxiety, though it did not improve the patient’s perception of fatigue. The lack of evidence for these approaches in treating children with fatigue in palliative care should not prevent their use, however, as with all treatment, the clinician, child, and family must be able to balance the potential good and harmful effects to establish what is in the child’s best interest before deciding on the course of action.

1 Hain R.D. Palliative care in children in Wales: a study of provision and need. Palliat Med. 2005;19(2):137-142.

2 Health Professions Council. Standard 2b. Standards of Proficiency – Physiotherapists. 2007.

3 CAM basics Internet database. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/D347.pdf, 2007. Available from: (Accessed August 2, 2009

4 Cassileth B.R., Vickers A.J. Massage therapy for symptom control: outcome study at a major cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(3):244-249.

5 Gray R.A. The use of massage therapy in palliative care. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 2000;6(2):77-82.

6 Kutner J.S., Smith M.C., Corbin L., Hemphill L., Benton K., Mellis B.K., et al. Massage therapy versus simple touch to improve pain and mood in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6):369-379.

7 Lafferty W.E., Downey L., McCarty R.L., Standish L.J., Patrick D.L. Evaluating CAM treatment at the end of life: a review of clinical trials for massage and meditation. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14(2):100-112.

8 Pan C.X., Morrison R.S., Ness J., Fugh-Berman A., Leipzig R.M. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of pain, dyspnea, and nausea and vomiting near the end of life: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(5):374-387.

9 Post-White J., Fitzgerald M., Savik K., Hooke M.C., Hannahan A.B., Sencer S.F. Massage therapy for children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2009;26(1):16-28.

10 Sellick S.M., Zaza C. Critical review of 5 nonpharmacologic strategies for managing cancer pain. Cancer Prev Control. 1998;2(1):7-14.

11 Soden K., Vincent K., Craske S., Lucas C., Ashley S. A randomized controlled trial of aromatherapy massage in a hospice setting. Palliat Med. 2004;18(2):87-92.

12 Wilkie D., Kampbell J., Cutshall S., Halbisky H., Harmon H., Johnson L. Effects of massage on pain intensity, analgesics and quality of life in patients with cancer pain: a pilot study of a randomized clinical trial conducted within hospice care delivery. Hosp J. 2000;15:31-53.

13 Dillon M., Lucas C. Auricular stud acupuncture in palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 1999;13(3):253-254.

14 Filshie J. Acupuncture in palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2000;7(2):41-44.

15 Leng G. A year of acupuncture in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1999;13(2):163-164.

16 Liptak G.S. Complementary and alternative therapies for cerebral palsy. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(2):156-163.

17 Gadsby J., Franks A., Jarvis P., Dewhurst F. Acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation within palliative care: a pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 1997;5:13-18.

18 Robb K., Oxberry S.G., Bennett M.I., Johnson M.I., Simpson K.H., Searle R.D. A cochrane systematic review of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(4):746-753.

19 Robb K.A., Newham D.J., Williams J.E. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation vs. transcutaneous spinal electroanalgesia for chronic pain associated with breast cancer treatments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):410-419.

20 Klimach V.J. The community use of rescue medication for prolonged epileptic seizures in children. Seizure. 2009;18(5):343-346.

21 Uhlig T., Huppe M., Nidermaier B., Pestel G. Mood effects of zolpidem versus phenobarbital combined with promethazine in an anesthesiological setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1996;34(2):90-97.

22 Tremont-Lukats I.W., Megeff C., Backonja M.M. Anticonvulsants for neuropathic pain syndromes: mechanisms of action and place in therapy. Drugs. 2000;60(5):1029-1052.

23 Nahara M.C., McMorrow J., Jones P.R., Anglin D., Rosenberg R. Pharmacokinetics of midazolam in critically ill pediatric patients. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2000;25(3–4):219-221.

24 Kanegaye J.T., Favela J.L., Acosta M., Bank D.E. High-dose rectal midazolam for pediatric procedures: a randomized trial of sedative efficacy and agitation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(5):329-336.

25 Categories of life-limiting and life-threatening conditions. Available from www.act.org.uk/page.asp?section=164§ionTitle=Categories+and+life%2Dlimiting+and+life%2Dthreatening+conditions. Accessed January 10, 2010

26 Mariotti P., Fasano A., Contarino M.F., Della Marca G., Piastra M., Genovese O., et al. Management of status dystonicus: our experience and review of the literature. Mov Disord. 2007;22(7):963-968.

27 Bateman D.N., Rawlins M.D., Simpson J.M. Extrapyramidal reactions to prochlorperazine and haloperidol in the United Kingdom. Q J Med. 1986;59(230):549-556.

28 Starr P.A., Turner R.S., Rau G., Lindsey N., Heath S., Volz M., et al. Microelectrode-guided implantation of deep brain stimulators into the globus pallidus internus for dystonia: techniques, electrode locations, and outcomes. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17(1):E4.

29 Schlaggar B.L., Mink J.W. Movement disorders in children. Pediatr Rev. 2003;24(2):39-51.

30 Tilton A. Management of spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2009;16(2):82-89.

31 Albright A.L., Ferson S.S. Intrathecal baclofen therapy in children. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21(2):e3.

32 Kolaski K., Logan L.R. A review of the complications of intrathecal baclofen in patients with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(5):383-395.

33 Sansone J.M., Mann D., Noonan K., McLeish D., Ward M., Iskandar B.J. Rapid progression of scoliosis following insertion of intrathecal baclofen pump. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(1):125-128.

34 Senaran H., Shah S.A., Presedo A., Dabney K.W., Glutting J.W., Miller F. The risk of progression of scoliosis in cerebral palsy patients after intrathecal baclofen therapy. Spine (Phila, Pa 1976). 2007;32(21):2348-2354.

35 Ginsburg G.M., Lauder A.J. Progression of scoliosis in patients with spastic quadriplegia after the insertion of an intrathecal baclofen pump. Spine (Phila, Pa 1976). 2007;32(24):2745-2750.

36 Vissers K.C., Geenen F., Biermans R., Meert T.F. Pharmacological correlation between the formalin test and the neuropathic pain behavior in different species with chronic constriction injury. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84(3):479-486.

37 Yomiya K., Matsuo N., Tomiyasu S., Yoshimoto T., Tamaki T., Suzuki T., et al. Baclofen as an adjuvant analgesic for cancer pain. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(2):112-118.

38 Simpson D.M., Gracies J.M., Graham H.K., Miyasaki J.M., Naumann M., Russman B., et al. Assessment: Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of spasticity (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70(19):1691-1698.

39 Albavera-Hernandez C., Rodriguez J.M., Idrovo A.J. Safety of botulinum toxin type A among children with spasticity secondary to cerebral palsy: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(5):394-407.

40 Stirling L.C., Kurowska A., Tookman A. The use of phenobarbitone in the management of agitation and seizures at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(5):363-368.

41 Lynn A.M., McRorie T.I., Slattery J.T., Calkins D.F., Opheim K.E. Age-dependent morphine partitioning between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in monkeys. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1991;17(3–4):200-204.

42 Mercadante S., Arcuri E. Opioids and renal function. J Pain. 2004;5(1):2-19.

43 Adlington K., Liu A.J., Nanan R. Sleep disturbances in the disabled child: a case report and literature review. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(9):711-715.

44 Zucconi M., Bruni O. Sleep disorders in children with neurologic diseases. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2001;8(4):258-275.

45 Wood F., Simpson S., Barnes E., Hain R. Disease trajectories in paediatric palliative care: towards validation of the ACT/RCPH categories. Palliat Med. 2010. In press.

46 Lardone P.J., Carrillo-Vico A., Naranjo M.C., De Felipe B., Vallejo A., Karasek M., et al. Melatonin synthesized by Jurkat human leukemic T cell line is implicated in IL-2 production. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206(1):273-279.

47 Hancock E., O’Callaghan F., Osborne J.P. Effect of melatonin dosage on sleep disorder in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(1):78-80.

48 Sateia M., Santulli R. Sleep in palliative care. In Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherny N.I., Calman K., editors: Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 3, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

49 Goldman A., Hewitt M., Collins G.S., Childs M., Hain R. Symptoms in children/young people with progressive malignant disease: United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group/Paediatric Oncology Nurses Forum survey. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1179-e1186.

50 Hechler T., Blankenburg M., Friedrichsdorf S.J., Garske D., Hubner B., Menke A., et al. Parents’ perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin Padiatr. 2008;220(3):166-174.

51 Jalmsell L., Kreicbergs U., Onelov E., Steineck G., Henter J.I. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1314-1320.

52 Pritchard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., Okuma J., Anderson L., Powell B., et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1301-e1309.

53 Theunissen J.M., Hoogerbrugge P.M., van Achterberg T., Prins J.B., Vernooij-Dassen M.J., van den Ende C.H. Symptoms in the palliative phase of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(2):160-165.

54 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., Levin S.B., Ellenbogen J.M., Salem-Schatz S., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

55 Stone P.C., Minton O. Cancer-related fatigue. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1097-1104.

56 Ullrich C.K., Mayer O.H. Assessment and management of fatigue and dyspnea in pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):735-756. xi

57 Batchelor T.T., Taylor L.P., Thaler H.T., Posner J.B., DeAngelis L.M. Steroid myopathy in cancer patients. Nuerology. 1997;48:1234-1238.

58 National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression in Children and Young People Identification and management in primary, community and secondary care. London: The British Psychological Society, 2005.

59 Breitbart W., Rosenfeld B., Kaim M., Funesti-Esch J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of psychostimulants for the treatment of fatigue in ambulatory patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(3):411-420.

60 Bruera E., Miller M.J., Macmillan K., Kuehn N. Neuropsychological effects of methylphenidate in patients receiving a continuous infusion of narcotics for cancer pain. Pain. 1992;48(2):163-166.

61 Bruera E., Valero V., Driver L., Shen L., Willey J., Zhang T., et al. Patient-controlled methylphenidate for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):2073-2078.

62 Yee J.D., Berde C.B. Dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate as adjuvants to opioid analgesia for adolescents with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994;9(2):122-125.

63 Cramp F., Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008. CD006145

64 Frenkel M., Shah V. Complementary medicine can benefit palliative care, Part 1. Eur J Palliat Care. 2008;15(5):238-243.

65 Thompson E.A., Reillly D. The homeopathic approach to symptom control in the cancer patient: a prospective observational study. Palliat Med. 2002;16(3):227-233.

66 Williams P.D., Schmideskamp J., Ridder E.L., Williams A.R. Symptom monitoring and dependent care during cancer treatment in children: pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(3):188-197.