chapter 13 Neurological Examination

The Logic Behind the Approach

At each phase of the assessment, try to determine the site of the lesion. Doing so makes it easier to compile a list of differential diagnoses or hypotheses. As an initial approach, divide neurological disorders into upper motor neuron lesions (UMNLs) and lower motor neuron lesions (LMNLs). The major features of each are listed in Table 13–1. Remember that some children, such as those with leukodystrophies, may have a mixture of both UMNL and LMNL signs, and localizing the problem to a single focal lesion in such patients is not possible. In addition, children with disorders of the cerebellum or basal ganglia do not have UMNL signs.

| Parameters | Upper Motor Neuron Lesions: Central Nervous System Dysfunction* | Lower Motor Neuron Lesions: Peripheral Nervous System Dysfunction† |

|---|---|---|

| Intellect | Deficits may be found with cortical abnormalities | Normal |

| Cranial nerves | Abnormalities usually reflect brainstem involvement but may indicate a neuropathy | May be involved |

| Power | Slightly decreased, although movement more severely impaired because of altered tone | Markedly reduced; neuromuscular junction disease associated with fatigue |

| Tone | Increased (spasticity) with lesions affecting pyramidal pathways; rigidity seen with extrapyramidal disease | Reduced (floppy or hypotonic) |

| Coordination | Impaired when cerebellum or its connections are involved | May be hindered by weakness |

| Reflexes | Hyperactive in pyramidal dysfunction; plantar stimulation results in an extensor response (Babinski) in the great toe | Difficult to elicit |

| Sensation | Usually intact, but spinal cord gives a sensory level that is in a dermatomal distribution | Impaired with lesions that affect the nerve |

| Fasciculations | Present with anterior horn cell disease but occasionally also found with neuropathies |

* Involve intracranial contents, brainstem, or spinal cord.

† Involve intracranial horn cells, nerves, neuromuscular junction, or muscles.

Obtaining the History

When combined with a hands-off observation, the history usually provides the diagnosis (see Chapter 1). The physical examination rarely reveals previously unsuspected findings.

The school-aged child

A brief but detailed history of the pregnancy is essential. Most mothers remember the pregnancy and birth in vivid detail and often have unfounded fears related to it (see Chapter 1). Reassuring a mother that the cough medicine she took during the third trimester was not the cause of her baby’s meningomyelocele may relieve anxiety. Similarly, if a child has been discharged from the neonatal unit at the same time as his/her mother, it is extremely unlikely that significant perinatal problems occurred.

Observation

The school-aged child

Power

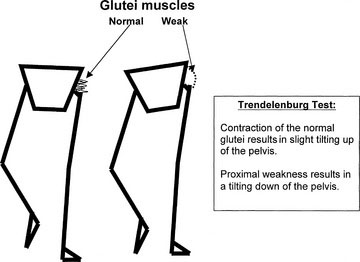

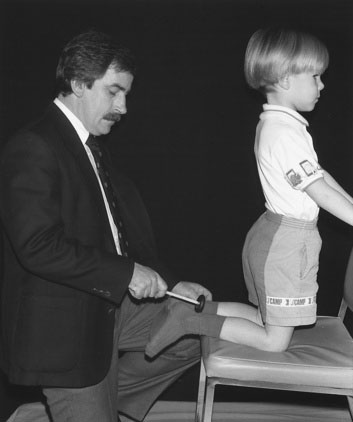

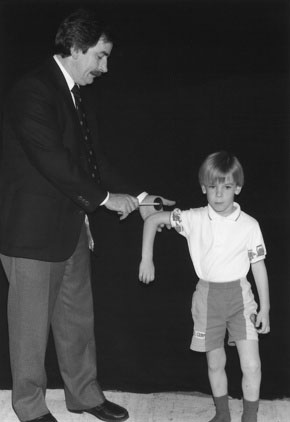

Proximal leg weakness, seen in myopathies such as muscular dystrophy, may be apparent if the child walks with a waddling gait. The Trendelenburg sign indicates a weakness of the hip abductors and is reflective of proximal weakness. Normally, when the child stands on one leg, the glutei contract, and the other side of the pelvis is tilted slightly upward. When the child has proximal weakness, the glutei are not sufficiently strong, and the other hip tilts downward. To maintain balance, the trunk leans over toward the side of the lesion; this is called the Trendelenburg sign (Fig. 13–1). Weakness and wasting of the hand muscles are more likely to indicate a neuropathy. Note that proximal weakness indicates a myopathy, and distal weakness indicates a neuropathy. Myotonic dystrophy, a dominantly inherited myopathy characterized by distal weakness and the inability to relax the muscles, is essentially the only major exception to this rule in childhood. During the period of observation, look for any asymmetry in limb movements. (See Video 13-3 on Student Consult.)

Coordination

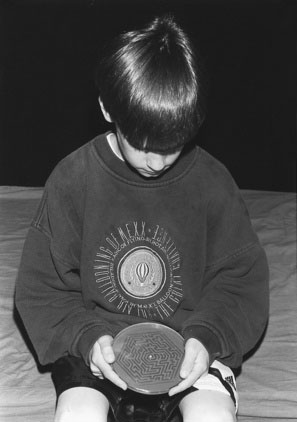

For older children, I use a challenging maze puzzle, which is an excellent test of coordination (Fig. 13–2). Cerebellar lesions affect the ipsilateral limb.

Reflexes and Sensation

Reflexes and sensation are examined during the physical examination, which is described later.

Abnormal Movements

The more common abnormal movements are described here:

The preschool-aged child

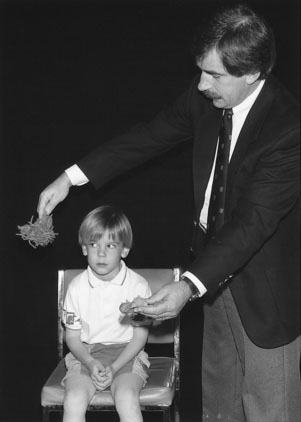

In the younger child, a period of hands-off observation should always be the first part of the physical examination. I give puzzles, a pencil, and paper to the younger child. Giving children toys allows you to observe the youngster’s manual dexterity, coordination, developmental competence, and handedness (Fig. 13–3). Observe the parent-child interaction closely. You may detect discipline problems at this stage. Drawings also reveal visual-spatial abilities, fine motor skills, and the child’s level of attention. Allowing the child to play also provides important undisturbed time with the parents as you take the history.

The Physical Examination

The school-aged child

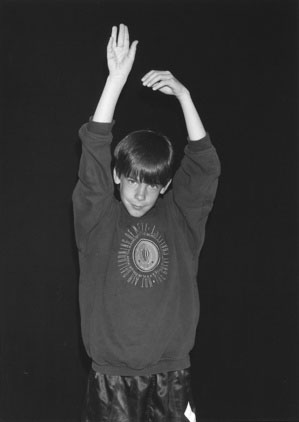

Holding the extended and supinated arms in front of the body also tests for weakness. Children with a mild weakness will be unable to maintain this position, and the arms tend to drift downward, flex at the elbow, and pronate (Fig. 13–4).

Cortical Function

School-aged and preschool-aged children

Assess each cortical area in turn.

Temporal Lobes

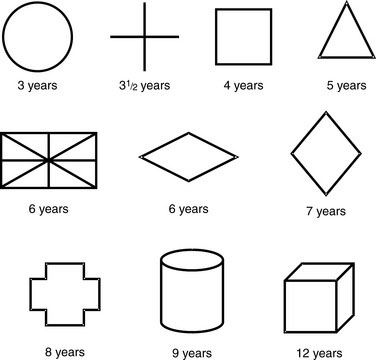

Temporal lobe impairment may cause personality changes similar to those seen with frontal lobe damage. Language is also represented in this lobe, and lesions of the superior and middle gyri cause Wernicke aphasia, characterized by an impaired comprehension of word elements. The ability to read, write, and understand speech may be altered. If the nondominant temporal lobe is involved, the child has a distorted perception of spatial relationships and a change in musical appreciation. Test for alterations in spatial perception by asking the child to copy geometric designs. Age-appropriate designs are shown in Figure 13–5. Bilateral involvement of the hippocampus interferes with learning. Temporal lobe injury also may produce psychotic aggressive behavior. Visual symptoms are usually represented by a homonymous superior quadrantanopia.

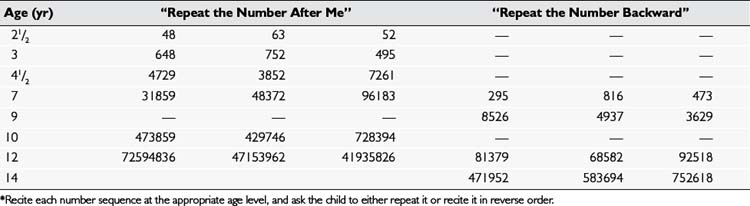

Memory deficits may be seen with a temporal lobe dysfunction. You can test a child’s immediate recall by reciting number sequences and having the child repeat them after you, either in the same order or in reverse; Table 13–2 gives examples of age-appropriate number sequences for this test.

Cranial Nerve II (Optic)

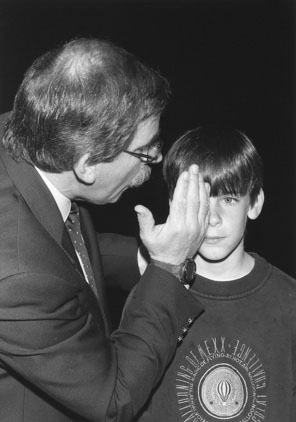

Always separately test each eye (see Chapter 8), and divide the examination into the following four parts.

Visual fields

The Preschool-Aged Child

For the younger child, test the visual fields by distracting him or her with a toy in front while bringing a red toy from behind the youngster into the peripheral field of vision (Fig. 13–6). The child with normal vision should respond as soon as the toy reaches a line perpendicular to the outer canthus of the eye.

Visual acuity

The School-Aged Child

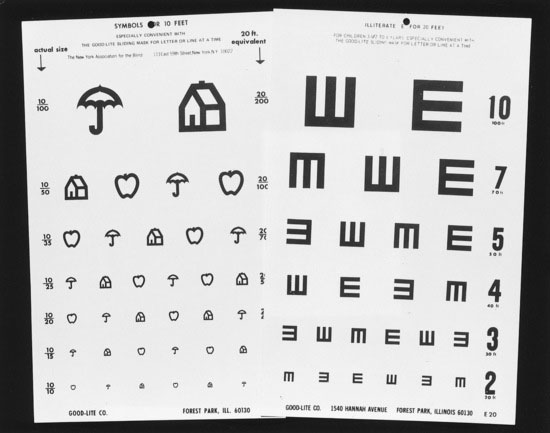

Visual acuity can be tested in adults, although some children with learning problems (e.g., dyslexia) should be tested with charts that contain images rather than letters (Fig. 13–7).

Fundoscopy

The Preschool-Aged Child

The Infant

For infants, two techniques are valuable. Allowing an infant to suck on an object (even your finger) usually induces eye opening, and you can view the fundi without difficulty. Alternatively, have the parent hold the baby so that he or she is looking over one of the parent’s shoulders. You can hold the baby’s head gently but firmly while viewing the fundi (Fig. 13–8).

Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI (Oculomotor, Trochlear, And Abducens)

Cranial Nerve V (Trigeminal)

The trigeminal nerves are responsible for the muscles of mastication and for sensation to the face.

Cranial Nerve VII (Facial)

All three age groups

The corneal reflex depends on the fifth (afferent) and seventh (efferent) cranial nerves. Test this reflex by touching the cornea with a wisp of cotton, which is brought to the eye from the side, outside the field of vision. A substitute for this unpleasant test involves blowing gently over the cornea of one eye while your hand protects the other eye from stimulation (Fig. 13–9).

Cranial Nerve VIII (Cochlear and Vestibular)

Cranial Nerves IX And X (Glossopharyngeal and Vagus)

Physical Examination of the Trunk and Extremities

Lower extremities

Power

Observe the muscle bulk for wasting. In neuropathies, the wasting occurs distally and can produce pes cavus (Fig. 13–10). Diagnose pes cavus when light is seen under the arch, despite pressing a hard object, such as a book, firmly against the sole of the foot. A hypertrophic appearance of the calf muscles in conjunction with proximal muscle weakness suggests muscular dystrophy (actually pseudohypertrophy because of fatty infiltration of muscles). These pseudohypertrophic muscles feel “rubbery” to palpation. Fasciculations as a result of spontaneous contractions of muscle fiber groups are seen primarily with AHC dysfunction but also occasionally with neuropathies. They can be heard as crackling sounds when you listen over the muscle with the bell of your stethoscope.

The School-Aged Child. Undertake more formal testing with the school-aged child lying supine. Test each muscle group separately. It is useful to use a grading scale, but it is essential to document the scale you have used. I frequently find notes in charts that indicate that the muscle strength in a patient’s biceps was “3/6.” What does this mean? One commonly used scale is outlined in Table 13–3. As part of the routine examination, you should test

| 0 | No muscle contraction |

| 1 | Flicker of contraction |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Movement against gravity |

| 4 | Movement against resistance |

| 5 | Normal power |

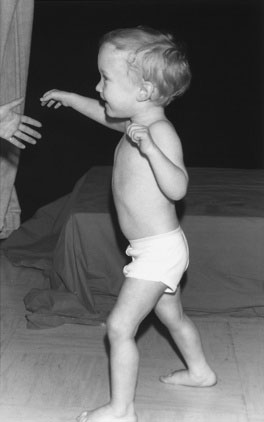

The Preschool-Aged Child. Place young or uncooperative preschool-aged patients on the floor. Even the most stubborn child eventually gets up. As he or she arises, assess the leg strength. Proximal weakness is characterized by the use of the arms to help the child “climb” up the legs (Gower sign) (see Chapter 15). Children older than 3 years should be able to stand briefly on one foot. A child who is reluctant to perform these tasks usually cooperates if you do the tasks at the same time. If this approach does not work, remember that every child rises to tiptoes to reach for an interesting toy. These maneuvers allow the avoidance of the difficult question of what is acceptable strength for a child. All children should be able to support their body weight.

Tone

The Preschool-Aged Child and the Infant. When the young child or infant is lifted in the air, the “scissoring” of the legs (Fig. 13–11) indicates increased tone (spasticity, UMNL) in the hip adductors. Because of tightness in the hip adductors, the child with increased tone also tends to sit on the floor in the W position, with the thighs and knees touching each other.

Reflexes

School-Aged and Preschool-Aged Children. It is easy to elicit knee reflexes when you sit opposite the school-aged or preschool-aged child and rest his or her feet on your own knees. The angle at the child’s knees should be symmetric and approximately 120 degrees. With the legs in this position, it is easy to demonstrate the reflexes by tapping just below the patella (Fig. 13–12). I discourage the use of tomahawk reflex hammers. Those with a wheel at the top work best.

You can easily obtain the ankle reflex by holding the foot at 90 degrees with your thumb on the plantar aspect and your other fingers over the dorsum. The reflex can be seen when you strike your own thumb with the hammer. If you find it difficult to elicit an ankle reflex, ask the child to kneel on the examining table or chair with his or her heels over the edge (Fig. 13–13), and tap over the Achilles tendon. Before concluding that a reflex is absent, try the same maneuver while you have the child clenching his or her teeth as hard as possible and trying to pull his or her interlocked fingers apart. Reflexes with a slow relaxation phase (especially ankle jerks) are seen in children with hypothyroidism.

If these precautions are taken, the great toe plantar flexes in the vast majority of infants, as it does in older children.

Sensation

Test vibration sense using a tuning fork (128 Hz) placed over a distal phalanx. Ask the child to tell you when the vibration stops, and compare this response with your own ability to perceive vibration. To test proprioception, secure the toe or finger by holding its lateral aspects and move only the most distal phalanx. A tiny movement of 10 to 20 degrees is normally appreciated (Fig. 13–15).

Before allowing the child to dress, inspect the skin thoroughly for lesions associated with neurocutaneous syndromes. In neurofibromatosis, there are multiple café au lait spots. In tuberous sclerosis, facial adenoma sebaceum may be mistaken for acne. Patients with this disorder also have depigmented spots (Fig. 13–16) that may have a leaf shape (ash leaf spots). The Sturge-Weber syndrome is characterized by a facial hemangioma that involves the first division of the trigeminal nerve and is associated with underlying abnormalities in the cerebral cortex on the same side. Children with this syndrome often have seizures and mental retardation in addition to other problems. Finally, check the spine for scoliosis and for cutaneous lesions. Children with a tuft of hair or apparent dermal sinus over the spine may have an underlying spinal cord lesion.

Upper extremities

Power

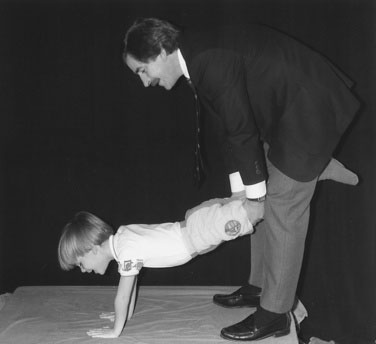

The Preschool-Aged Child and the Infant. Test upper extremity strength in the younger child by staging a wheelbarrow “race” (Fig. 13–17). In this maneuver, the arms support the total body weight.

Tone

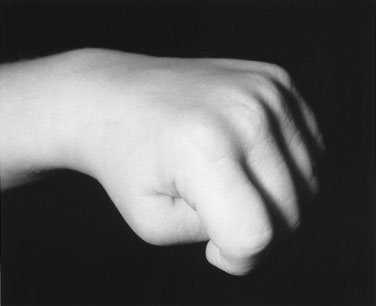

The School-Aged Child. Test tone in the upper extremities of the school-aged child by holding his or her hand and alternately pronating and supinating the forearm. Increased tone in the arms is often most apparent in the hands, where the thumbs are held tucked in under the fingers in a fisted position (Fig. 13–18). Your confidence in distinguishing normal and abnormal tone depends on the number of children you have examined. Take every opportunity to assess muscle tone in your pediatric patients, and you will quickly appreciate the range of normal muscle tone in children.

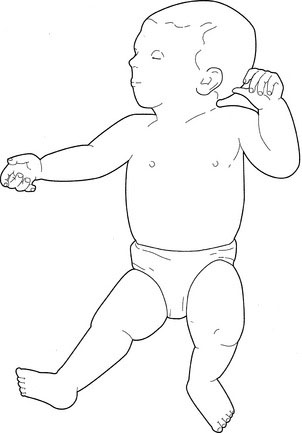

The Infant. Hold the infant in horizontal suspension. The floppy baby hangs like an inverted U (Fig. 13–19), whereas the spastic child hyperextends his or her trunk. When pulled to sit, the normal neonate shows some evidence of neck flexion. The scarf sign is a helpful test for upper extremity tone; to test for it, adduct the arm as far as possible. In the normal infant, the elbow can be brought to midline, touching the chin.

Reflexes

School-Aged and Preschool-Aged Children. Examine the deep tendon reflexes in a school-aged or preschool-aged child as you would in an adult. For the biceps reflex, the child’s arms should rest in his or her lap with the elbows partially flexed. I place my finger over the tendon and then hit my own finger, thus persuading the child I do not want to hurt him or her and also allowing me to feel muscle movement during the reflex. You can more easily test the triceps reflex by abducting the arm 90 degrees with the elbow flexed to 90 degrees (perpendicular to the ground) (Fig. 13–20). In this position, the reflex can be seen easily, and it is difficult for the child to resist. Elicit the Hoffman reflex by holding the patient’s hand in the pronated position and flicking down the terminal phalanx of the middle finger. In children with UMNL, the thumb flexes and adducts, and the other fingers also flex.

Sensation

Testing sensation in the arms is as described previously for the legs.

Case History 1

History. Six-year-old Peter is brought to see you because he frequently trips when running.

What should you observe?

As you watch Peter, you notice that he tends to turn his right foot in and swing his leg from the hip (circumduction) when he runs ahead of you in the hall (Fig. 13–21; Video 13-4 on Student Consult). While drawing, he holds the pencil in his left hand and keeps his right arm flexed tightly across his chest, supporting your suspicion that he has a hemiparesis. He has no evidence of weakness as he rises from the floor. Your conversation with him supports his mother’s claims that he is a smart little boy.

Case History 2

Case History 3

History. Jason, a 6-year-old boy, comes to you because of headaches.

What questions might you ask him?

Remember that the history that you obtain from Jason will be more valuable than that provided by his parents. Table 13–4 provides some guidelines for questions that might be valuable in this situation.

TABLE 13–4 Characteristics of Headache Pain and Possible Meaning

| Question | What the Answer May Indicate |

|---|---|

| When did headaches begin? | Chronic headaches are less likely to be due to significant disease. |

| Are they getting worse? | Headaches due to increased intracranial pressure often become progressively more severe. |

| Where are they located? | Migraine headaches switch from side to side. |

| Tension headaches tend to occur like a band around the head. | |

| Headaches due to increased intracranial pressure may always be located in the same position. | |

| What type is the pain? | Migraine is usually described as throbbing. |

| Tension headaches are typically “pressing,” but tumors (increased intracranial pressure) can produce throbbing, pressing, or sharp pain. | |

| When does the pain occur? | Migraine is episodic and often occurs in the afternoon but will occasionally wake the patient. |

| Tension headaches may last all day but do not interfere with sleep. | |

| Pain due to increased intracranial pressure is worse in early morning and may awaken the child. | |

| Does the headache interfere with play? | Migraine and increased intracranial pressure disrupt the child’s activities. |

| Tension headaches are complained of but do not interrupt anything; the child may use them to avoid unpleasant tasks. | |

| Are there associated symptoms? | Tension headaches are seldom associated with other symptoms. |

| Migraine is usually seen with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and visual symptoms such as flashing lights. | |

| Increased intracranial pressure results in vomiting and may cause diplopia, due to a VI nerve palsy. | |

| What relieves headache? | Migraine is relieved by a brief period of sleep. |

| Increased intracranial pressure is seldom relieved by any specific factor. | |

| Tension headaches are helped by stress reduction. | |

| Is there a family history of headaches? | Such a history is common in migraine and stress headaches. |

| Has the child shown any changes in personality, ability, or thinking? | Such changes are more likely to be associated with significant disease. |

| Are the headaches triggered by any foods, activities, or events? | Migraine is often triggered by stress, specific foods, or tiredness. |

The information shown in Table 13–4 should make it apparent that these findings are worrisome, suggesting raised intracranial pressure (ICP). The early-morning predominance reflects an aggravation of the slight increase in ICP that normally occurs at night.

Do the headaches interfere with play?

Insignificant headaches may prevent school attendance but not participation in sports and other pleasurable activities. Learning more details of a patient’s school performance is often an easy way to document cognitive function. Jason is described by his teachers as an excellent student who is always at the top of his class. He has had difficulty concentrating over the past 2 weeks, probably reflecting the severity of the headache pain. Children who have difficulties in school may have other problems, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or learning disabilities, which require a thorough developmental assessment (see Chapter 6).

Summary

The neurological examination can be made fun for children while allowing a thoughtful analytic approach to diagnosis. The use of simple instruments and toys (Fig. 13–22) can increase the child’s enjoyment of the experience. On completing the evaluation, first hypothesize the location of any deficit in the nervous system that might account for the findings; then try to decide what disease processes could produce such a lesion. Base the need for further investigations on the differential diagnosis, always forming a specific question that each investigation should answer. The most important part of the physical examination is the period of hands-off observation.

Dooley J., Gordon K. Ophthalmoscopy: A seven-step program. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35:237-242.

Fenichel G.M. 6th ed. Clinical pediatric neurology: a signs and symptoms approach. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2009.

Tindall B. Aids to the examination of the peripheral nervous system. London: WB Saunders, 2000.