Chapter 22 Neurological disease

The impact of neurological disease

Neurology is a large and diverse subject which covers many conditions that require long-term coordinated care and have serious effects on the daily lives of patients and their families. Neurology includes conditions as diverse as cognitive disorders involving higher level mental functioning through to disorders of peripheral nerve and skeletal muscle. It is a specialty requiring good clinical skills and examination technique which cannot be replaced with investigations or imaging techniques alone (Table 22.1).

| Conditions | Events per 100 000/year |

|---|---|

|

Cerebrovascular events |

210 |

|

Shingles (herpes zoster) and postherpetic neuralgia |

150 |

|

Diabetic and other neuropathies |

105 |

|

Epilepsy |

46 |

|

Parkinson’s disease |

19 |

|

Severe brain injury and subdural haematoma |

13 |

|

All CNS tumours |

9 |

|

Trigeminal neuralgia |

8 |

|

Meningitis |

7 |

|

Multiple sclerosis |

7 |

|

Presenile dementia (below 65 years) |

4 |

|

Myasthenia, all muscle and motor neurone disease |

5 |

Common symptoms and signs

Difficulty walking and falls

Change in walking pattern is a common complaint (Box 22.1). Arthritis and muscle pain make walking painful and slow (antalgic gait). The pattern of gait is valuable diagnostically.

Spasticity and hemiparesis

Spasticity (p. 1082), more pronounced in extensor muscles, with or without weakness, causes stiff and jerky walking. Toes of shoes become scuffed, catching level ground. Pace shortens; a narrow base is maintained. Clonus – involuntary extensor rhythmic leg jerking – may occur.

Parkinson’s disease: shuffling gait

There is muscular rigidity (p. 1118) throughout extensors and flexors. Power is preserved; the pace shortens, and slows to a shuffle; its base remains narrow. A stoop and diminished arm swinging become apparent. Gait becomes festinant (hurried) with short rapid steps. There is difficulty turning quickly and initiating movement, sometimes with falls. Retropulsion means small backward steps, taken involuntarily when a patient is halted.

Cerebellar ataxia: broad-based gait

In lateral cerebellar lobe disease (p. 1083) stance becomes broad-based, unstable and tremulous. Ataxia describes this incoordination. When walking, the person tends to veer to the side of the affected cerebellar lobe.

Sensory ataxia: stamping gait

Peripheral sensory lesions (e.g. polyneuropathy, p. 1145) cause ataxia because of loss of proprioception (position sense). Broad-based, high-stepping, stamping gait develops. This form of ataxia is exacerbated by removal of sensory input (e.g. vision) and worse in the dark. Romberg’s test, first described in sensory ataxia of tabes dorsalis (p. 1129), becomes positive.

Lower limb weakness: slapping and waddling gaits

When weakness is distal, each foot must be lifted over obstacles. When ankle dorsiflexors are weak, e.g. in a common peroneal nerve palsy (p. 1144), the sole returns to the ground with an audible slap.

Dizziness, vertigo and blackouts

Vertigo (p. 1078) means the illusion of movement, a sensation of rotation or tipping. The patient feels the surroundings are spinning or moving. This is distressing and often accompanied by nausea or vomiting.

Blackout, like dizziness, is simply descriptive, implying either altered consciousness, visual disturbance or falling. Epilepsy (p. 1112) and syncope are mentioned in detail (p. 1116); hypoglycaemia and anaemia must be considered. Commonly no sinister cause is found. A careful history is essential.

Examination and formulation

Following a short or detailed examination, relevant findings are summarized in a brief formulation – the basis for investigation, transfer of information and management (Practical Boxes 22.1, 22.2 and Table 22.2).

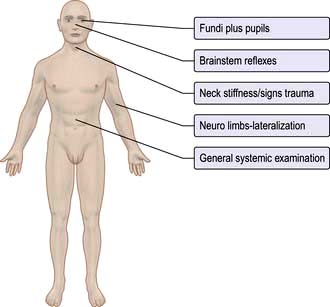

![]() Practical Box 22.2

Practical Box 22.2

10-part neurological examination

1. State of consciousness, arousal, appearance

2. Mental state, attitude, insight (see Box 22.5, p. 1069)

3. Cognitive function – orientation, recall, level of intellect, language, other cortical problems, e.g. apraxia

6. Neck – stiffness, palpation and auscultation of carotids

7. Cranial nerves (Table 22.3)

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

|

5 |

Normal power |

|

4 |

Active movement against gravity and resistance |

|

3 |

Active movement against gravity |

|

2 |

Active movement with gravity eliminated |

|

1 |

Flicker of contraction |

|

0 |

No contraction |

Functional neuroanatomy

The neurone and synapse

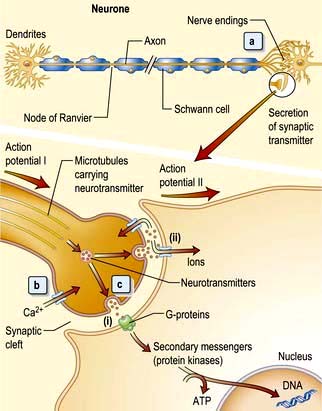

The neurone is the functional unit of the entire nervous system (Fig. 22.1). Its cell body and axon terminate in a synapse. Size and type of each group of neurones vary. A thoracic spinal cord α-motor neurone has an axonal length of >1 metre and innervates between several hundred and 2000 muscle fibres in one leg – a motor unit. By contrast, some spinal or intracerebral interneurones have axons under 100 µm long, terminating on one neuronal cell body.

Clinical features of focal brain lesions: general mechanisms

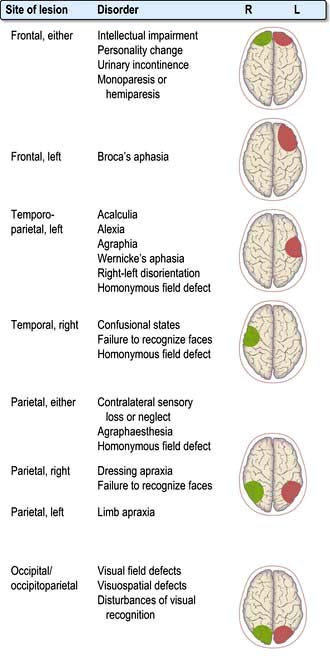

Suppression or destruction of neurones and surrounding structures (Fig. 22.2). This is the commonest process – part of the system simply fails to work.

Suppression or destruction of neurones and surrounding structures (Fig. 22.2). This is the commonest process – part of the system simply fails to work.

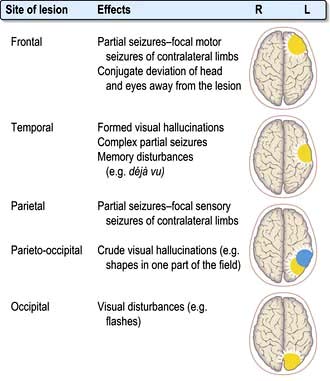

Synchronous discharge of neurones by irritative lesions (Fig. 22.3), e.g. cortical lesions, causes epilepsy, either partial or generalized.

Synchronous discharge of neurones by irritative lesions (Fig. 22.3), e.g. cortical lesions, causes epilepsy, either partial or generalized.

Localization within the cerebral cortex

Aphasia

Dysarthria

Dysarthria is disordered articulation – slurred speech. Language is intact. Paralysis, slowing or incoordination of muscles of articulation or local discomfort causes various patterns of dysarthria. Examples are the gravelly speech of pseudobulbar palsy (p. 1080), the jerky, ataxic speech of cerebellar lesions, the monotone of Parkinson’s, and speech in myasthenia that fatigues and dies away. Many aphasic patients are also dysarthric.

Memory and its disorders

Memory loss (the amnestic syndrome) is part of dementia (p. 1137) but also occurs as an isolated entity (Box 22.2).

Cranial nerves (Table 22.3)

I: Olfactory nerve

| Number | Name | Main clinical action |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

Olfactory |

Smell |

|

II |

Optic |

Vision, fields, afferent light reflex |

|

III |

Oculomotor |

Eyelid elevation, eye elevation, ADduction, depression in ABduction, efferent (pupil) |

|

IV |

Trochlear |

Eye intorsion, depression in ADduction |

|

V |

Trigeminal |

Facial (and corneal) sensation, mastication muscles |

|

VI |

Abducens |

Eye ABduction |

|

VII |

Facial |

Facial movement, taste fibres |

|

VIII |

Vestibular |

Balance and hearing |

|

|

Cochlear |

|

|

IX |

Glossopharyngeal |

Sensation – soft palate, taste fibres |

|

X |

Vagus |

Cough, palatal and vocal cord movements |

|

XI |

Accessory |

Head turning, shoulder shrugging |

|

XII |

Hypoglossal |

Tongue movement |

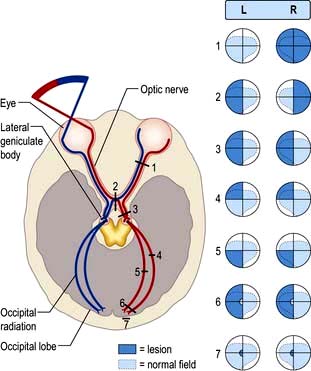

II: Optic nerve and visual system (Fig. 22.4)

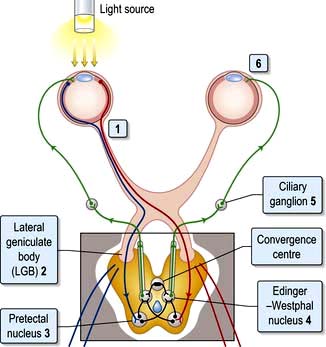

Light regulated by the pupillary aperture is converted into action potentials by retinal rod, cone and ganglion cells (see page 1055). The lens, under control of the ciliary muscle, produces the image (inverted) on the retina. Axons in the optic nerve (1) decussate at the optic chiasm (2), fibres from the nasal retina cross and join with uncrossed fibres originating in the temporal retina to form the optic tract (3). Each optic tract thus carries information from the contralateral visual hemifield.

From the lateral geniculate body, fibres pass in the optic radiation through the parietal and temporal lobes (4 and 5) to reach the visual cortex of the occipital lobe (6 and 7), which is somatotopically organized with macular vision located at the occipital pole (see Fig. 22.4).

Visual field defects

Optic nerve lesions

Reduced acuity in affected eye

Reduced acuity in affected eye

Impaired colour vision (assess with Ishihara plates)

Impaired colour vision (assess with Ishihara plates)

Causes are listed in Box 22.3.

![]() Box 22.3

Box 22.3

Causes of optic neuropathy

Inflammatory (optic neuritis), e.g. demyelination, sarcoidosis, vasculitis

Inflammatory (optic neuritis), e.g. demyelination, sarcoidosis, vasculitis

Optic nerve trauma or compression, e.g. glioma, meningioma, aneurysm, bone disorders affecting orbit

Optic nerve trauma or compression, e.g. glioma, meningioma, aneurysm, bone disorders affecting orbit

Toxic, e.g. tobacco-alcohol, ethambutol, methyl alcohol, quinine, hydroxy chloroquine, radiation

Toxic, e.g. tobacco-alcohol, ethambutol, methyl alcohol, quinine, hydroxy chloroquine, radiation

Ischaemic optic neuropathy, e.g. giant cell arteritis

Ischaemic optic neuropathy, e.g. giant cell arteritis

Hereditary optic neuropathies, e.g. Leber’s

Hereditary optic neuropathies, e.g. Leber’s

Nutritional deficiency, e.g. vitamin B1 and B12

Nutritional deficiency, e.g. vitamin B1 and B12

Infection, e.g. orbital cellulitis, syphilis, TB

Infection, e.g. orbital cellulitis, syphilis, TB

Papilloedema

Papilloedema means swelling of the optic disc. Causes are shown in Box 22.4. The earliest signs of swelling are disc pinkness, with blurring and heaping up of disc margins, nasal first. There is loss of spontaneous pulsation of retinal veins within the disc. The physiological cup becomes obliterated, the disc engorged with dilated vessels. Small haemorrhages often surround the disc.

![]() Box 22.4

Box 22.4

Causes of optic disc swelling

Raised intracranial pressure (papilloedema)

Raised intracranial pressure (papilloedema)

Brain tumour, abscess, or haemorrhage. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus

Brain tumour, abscess, or haemorrhage. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus

Optic neuritis, e.g. multiple sclerosis

Optic neuritis, e.g. multiple sclerosis

Ischaemic optic neuropathy, e.g. giant cell arteritis

Ischaemic optic neuropathy, e.g. giant cell arteritis

Toxic optic neuropathy, e.g. methanol

Toxic optic neuropathy, e.g. methanol

Central retinal vein thrombosis

Central retinal vein thrombosis

Vasculitis, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus

Vasculitis, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus

Various conditions simulate true disc swelling. Marked hypermetropic (long-sighted) refractive errors make a disc appear pink, distant and ill-defined. Myelinated nerve fibres at disc margins and hyaline bodies (drusen, p. 1064) can be mistaken for disc swelling.

Disc infiltration also causes a swollen disc with raised margins (e.g. in leukaemia).

Inflammatory optic neuropathy (optic neuritis)

A plaque of demyelination within the optic nerve is the most common cause in Western populations. Dedicated MRI imaging of the optic nerves may show the inflammatory plaque and imaging of the brain may show additional inflammatory lesions which confer a higher risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS). Approximately 50% of patients go on to develop MS with prolonged follow-up (see p. 1123). Recovery of visual acuity to 6/9 or better occurs in 95% of cases over months, with recovery time improved by high-dose i.v. steroids given acutely.

Optic neuritis may be caused by infective or other inflammatory disorders, e.g. sarcoidosis or vasculitides (see Box 22.3).

Occipital cortex

Homonymous hemianopic defects are produced by unilateral posterior cerebral artery infarction (see p. 1101 stroke). The macular cortex (at each occipital pole) may be spared.

Widespread bilateral occipital lobe damage by infarction (‘top of the basilar’ syndrome), trauma or coning causes cortical blindness (Anton’s syndrome). The patient cannot see but characteristically lacks insight into this; he or she may even deny it. Pupillary responses remain normal (p. 1101).

The pupils

Pupillary reactions to light and accommodation may be tested (Fig. 22.5). A bright torch (not an ophthalmoscope light!) should be used to test the pupillary light reaction.

The pupil is unreactive to light (i.e. the direct reflex is absent).

The pupil is unreactive to light (i.e. the direct reflex is absent).

The consensual reflex (constriction of the right pupil when the left is illuminated) is absent. Conversely, the left pupil constricts when light is shone in the intact right eye, i.e. the consensual reflex of the right eye remains intact.

The consensual reflex (constriction of the right pupil when the left is illuminated) is absent. Conversely, the left pupil constricts when light is shone in the intact right eye, i.e. the consensual reflex of the right eye remains intact.

Direct and indirect reflexes are intact in each eye but differ in relative strength.

Direct and indirect reflexes are intact in each eye but differ in relative strength.

When the light is swung from one eye to the other, the left pupil dilates slightly when illuminated and constricts slightly when the right eye is illuminated (the consensual reflex is stronger than the direct).

When the light is swung from one eye to the other, the left pupil dilates slightly when illuminated and constricts slightly when the right eye is illuminated (the consensual reflex is stronger than the direct).

Horner’s syndrome (see Box 22.5)

![]() Box 22.5

Box 22.5

Causes of Horner’s syndrome

III, IV, VI: Oculomotor, trochlear and abducens nerves

Control of eye movements

the ipsilateral occipital cortex – pathway concerned with tracking objects

the ipsilateral occipital cortex – pathway concerned with tracking objects

the vestibular nuclei – pathways linking eye movements with position of the head and neck (vestibulo-ocular reflex, p. 1072).

the vestibular nuclei – pathways linking eye movements with position of the head and neck (vestibulo-ocular reflex, p. 1072).

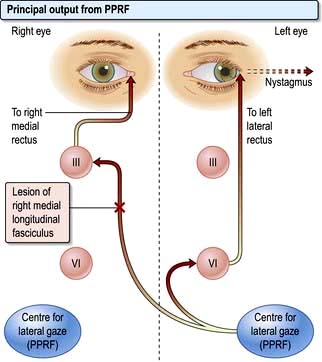

Conjugate lateral eye movements are coordinated from each PPRF via the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF, Fig. 22.6). Fibres from the PPRF pass both to the ipsilateral VIth nerve nucleus (lateral rectus) and, having crossed the midline, to the opposite IIIrd nerve nucleus (medial rectus and other muscles) via the MLF, thus linking the eyes for lateral gaze.

Abnormalities of conjugate lateral gaze

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO)

Damage to one MLF causes internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), a common complex brainstem eye movement disorder seen frequently in MS. In a right INO there is a lesion of the right MLF (Fig. 22.6). On attempted left lateral gaze the right eye fails to ADduct. The left eye develops nystagmus in ABduction. The side of the lesion is on the side of impaired ADduction, not on the side of the (obvious, unilateral) nystagmus. When present bilaterally, INO is almost pathognomonic of MS.

Nystagmus

Jerk nystagmus

Horizontal or rotary jerk nystagmus may be either of peripheral (vestibular) or central origin (VIIIth nerve, brainstem, cerebellum and connections).

Horizontal or rotary jerk nystagmus may be either of peripheral (vestibular) or central origin (VIIIth nerve, brainstem, cerebellum and connections).

Vertical jerk nystagmus is caused typically by central lesions.

Vertical jerk nystagmus is caused typically by central lesions.

Down-beat jerk nystagmus is a rarity caused by lesions around the foramen magnum (e.g. meningioma, cerebellar ectopia).

Down-beat jerk nystagmus is a rarity caused by lesions around the foramen magnum (e.g. meningioma, cerebellar ectopia).

III: Oculomotor nerve

The nucleus of the IIIrd nerve lies ventral to the aqueduct in the midbrain. It supplies four external ocular muscles (superior, inferior and medial recti, and inferior oblique), levator palpebrae superioris (which lifts the eyelid) and parasympathetic constriction of the pupil. Causes of a IIIrd nerve lesion are listed in Box 22.6.

V: Trigeminal nerve

The largest cranial nerve; mainly sensory with a motor component to the muscles of mastication.

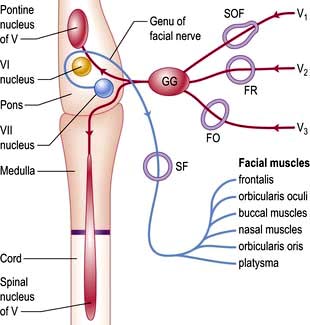

Sensory fibres (Fig. 22.7; see also Figs 22.11 and 22.12) of the three divisions – ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2) and mandibular (V3) – pass to the trigeminal (Gasserian) ganglion at the apex of the petrous temporal bone. Ascending fibres transmitting light touch enter the Vth nucleus in the pons. Descending central fibres carrying pain and temperature form the spinal tract of V, to end in the spinal Vth nucleus that extends from the medulla into the cervical cord.

Causes

Brainstem pathology (infarction, demyelination or tumour) may damage the nucleus, with light touch and spinothalamic pathways sometimes being differentially involved.

Brainstem pathology (infarction, demyelination or tumour) may damage the nucleus, with light touch and spinothalamic pathways sometimes being differentially involved.

Cerebellopontine angle tumours (acoustic neuroma or meningioma) may compress the nerve and also affect the VIIth and VIIIth nerves producing facial weakness and deafness.

Cerebellopontine angle tumours (acoustic neuroma or meningioma) may compress the nerve and also affect the VIIth and VIIIth nerves producing facial weakness and deafness.

Cavernous sinus and skull base pathology (tumour or infection) may affect the ganglion and proximal branches.

Cavernous sinus and skull base pathology (tumour or infection) may affect the ganglion and proximal branches.

Peripheral branches may be picked off individually, e.g. the ‘numb chin syndrome’ seen with a breast cancer metastasis in the mandible.

Peripheral branches may be picked off individually, e.g. the ‘numb chin syndrome’ seen with a breast cancer metastasis in the mandible.

VII: Facial nerve

The VIIth nerve is largely motor, supplying muscles of facial expression. VII carries sensory taste fibres from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue via the chorda tympani and supplies motor fibres to the stapedius muscle. The VIIth nerve (Fig. 22.7) arises from its nucleus in the pons and leaves the skull through the stylomastoid foramen. Neurones in each VIIth nucleus supplying the upper face (principally frontalis) receive bilateral supranuclear innervation.

Unilateral facial weakness

Causes of facial weakness

Pons. Here the VIIth nerve loops around the VIth (abducens) nucleus (Fig. 22.7), leading to a lateral rectus palsy (see p. 1076) with unilateral LMN facial weakness. When the neighbouring PPRF and corticospinal tract are involved, there is the combination of:

Causes include pontine tumours (e.g. glioma), MS and infarction.

Loss of taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue

Loss of taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue

Hyperacusis (loud noise distortion – paralysis of stapedius).

Hyperacusis (loud noise distortion – paralysis of stapedius).

Skull base, parotid gland and within the face. The facial nerve can be compressed by skull base tumours and in Paget’s disease of bone. Branches of VII may be damaged by parotid gland tumours as the nerve traverses the parotid, sarcoidosis (p. 845) and trauma.

Bell’s palsy

(Bell’s phenomenon is the upward conjugate eye movement that occurs when the eyes are closed.)

Hemifacial spasm (HFS)

HFS is usually caused by compression of the root entry zone of the facial nerve, generally by vascular structures such as the vertebral or basilar arteries or their branches (a mechanism similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia see p. 1110). Other mass lesions in the cerebellopontine angle, including tumours, are the cause in approximately 1% of cases.

VIII: Vestibulo-cochlear nerve; cochlear nerve

Symptoms of a cochlear nerve lesion are deafness and tinnitus (p. 1050). Sensorineural and conductive deafness can be distinguished with tuning fork tests, e.g. Rinne’s and Weber’s (256 Hz, not 128 Hz tuning fork) (p. 1048).

Basic investigations of cochlear lesions

Pure tone audiometry and auditory thresholds.

Pure tone audiometry and auditory thresholds.

Auditory evoked potentials (recording responses from repetitive clicks via scalp electrodes; lesion levels are determined from the response pattern).

Auditory evoked potentials (recording responses from repetitive clicks via scalp electrodes; lesion levels are determined from the response pattern).

Causes of deafness are listed in Table 22.4 and Table 21.1 (see p. 1048).

| Conditions | Symptom(s) |

|---|---|

|

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo |

V |

|

Vestibular neuritis |

V |

|

Ménière’s disease |

V, D |

|

Alcohol, antiepileptic drug intoxication |

V |

|

Cerebellar lesions |

V |

|

Partial (temporal lobe) seizures |

V |

|

Migraine |

V+ phonophobia |

|

Brainstem ischaemia |

V, occasionally D |

|

Multiple sclerosis |

V, occasionally D |

|

Mumps, intrauterine rubella and congenital syphilis (D) |

D |

|

Advancing age (presbyacusis) and otosclerosis (D) |

D |

|

Acoustic trauma (D) |

D |

|

Congenital, e.g. Pendred’s syndrome |

D |

|

Gentamicin, furosemide |

V, D |

|

Middle and external ear disease |

V, D |

|

Cerebellopontine angle lesions, e.g. acoustic neuroma |

V, D |

|

Carcinomatous meningitis, sarcoid and tuberculous meningitis |

V, D |

V, vertigo; D, hearing loss.

Vertigo and the vestibular system

The vestibular system of the inner ear detects head movements and has three primary functions:

To stabilize gaze during head movements, e.g. looking ahead while running (the vestibulo-ocular reflex)

To stabilize gaze during head movements, e.g. looking ahead while running (the vestibulo-ocular reflex)

The main symptoms of vestibular lesions are vertigo and loss of balance.

Vertigo

Vomiting frequently accompanies acute vertigo of any cause. Vertigo is always made worse by head movements and patients prefer to remain still and maintain visual fixation. Nystagmus (p. 1075) is the principal sign.

Causes of vertigo

Vertigo indicates a disturbance of the vestibular apparatus or brainstem and associated neural pathways (Table 22.4). Causes:

Peripheral (vestibular system) causes are common. Deafness and tinnitus accompanying vertigo indicate involvement of the ear or cochlear nerve (p. 1048).

Peripheral (vestibular system) causes are common. Deafness and tinnitus accompanying vertigo indicate involvement of the ear or cochlear nerve (p. 1048).

Central causes (brainstem and connections) are rarer. Other clinical features such as diplopia, weakness, cerebellar signs or cranial nerve palsies may help localize the lesion.

Central causes (brainstem and connections) are rarer. Other clinical features such as diplopia, weakness, cerebellar signs or cranial nerve palsies may help localize the lesion.

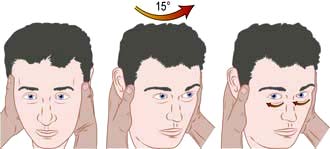

Vestibular disorders

Vestibular disorders are fully discussed elsewhere (p. 1049). Attack duration and frequency and trigger factors help the clinician distinguish on history between different pathological causes. The ability to perform a Hallpike test, head impulse test and Epley particle repositioning manoeuvre are invaluable skills for all clinicians (p. 1049; see Fig. 22.8 and Fig. 21.3).

The most commonly encountered vestibular disorders presenting with vertigo are:

Benign positional vertigo (BPPV) – frequent attacks lasting seconds only. Triggered by specific movements – lying down, sitting up or rolling over in bed, neck flexion or extension.

Benign positional vertigo (BPPV) – frequent attacks lasting seconds only. Triggered by specific movements – lying down, sitting up or rolling over in bed, neck flexion or extension.

Vestibular neuronitis – acute onset lasting days or weeks. Non-recurrent.

Vestibular neuronitis – acute onset lasting days or weeks. Non-recurrent.

Migrainous vertigo (p. 1108), really a central cause – lasting hours, occurring every few weeks or months

Migrainous vertigo (p. 1108), really a central cause – lasting hours, occurring every few weeks or months

Meniere’s disease – recurrent attacks lasting minutes or hours, usually accompanied by hearing loss, tinnitus and a feeling of fullness in the ear.

Meniere’s disease – recurrent attacks lasting minutes or hours, usually accompanied by hearing loss, tinnitus and a feeling of fullness in the ear.

Central causes of vertigo

Vertigo may be a manifestation of brainstem pathology including:

Infarcts involving the vestibular nuclei in the medulla (e.g. the lateral medullary syndrome)

Infarcts involving the vestibular nuclei in the medulla (e.g. the lateral medullary syndrome)

Demyelination involving the brainstem

Demyelination involving the brainstem

Posterior fossa mass lesions, e.g. tumours, haemorrhage or vascular malformations

Posterior fossa mass lesions, e.g. tumours, haemorrhage or vascular malformations

CPA mass lesions and tumours compressing the vestibular nerve (technically these should be classified as ‘peripheral’ disorders, but are distinct from disorders of the vestibular apparatus)

CPA mass lesions and tumours compressing the vestibular nerve (technically these should be classified as ‘peripheral’ disorders, but are distinct from disorders of the vestibular apparatus)

Basic investigations for vestibular problems

Bedside assessment is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis in the majority of patients:

Examination of eye movements for nystagmus (p. 1074)

Examination of eye movements for nystagmus (p. 1074)

Assessment of hearing and otoscopic examination of the ear (p. 1047)

Assessment of hearing and otoscopic examination of the ear (p. 1047)

Head impulse (thrust) test – to assess the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and identify a unilateral vestibulopathy

Head impulse (thrust) test – to assess the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) and identify a unilateral vestibulopathy

Hallpike manoeuvre – a positioning test to stimulate the posterior semicircular canal and trigger an attack in BPPV (see Fig. 21.3)

Hallpike manoeuvre – a positioning test to stimulate the posterior semicircular canal and trigger an attack in BPPV (see Fig. 21.3)

Caloric testing – irrigation of the external auditory, meatus with cold and then warm water to stimulate the horizontal semicircular canal and induce nystagmus. Test labyrinthine function in each ear separately.

Caloric testing – irrigation of the external auditory, meatus with cold and then warm water to stimulate the horizontal semicircular canal and induce nystagmus. Test labyrinthine function in each ear separately.

Electro-nystagmography – to quantify and characterize nystagmus under different conditions, e.g. in a rotating chair.

Electro-nystagmography – to quantify and characterize nystagmus under different conditions, e.g. in a rotating chair.

Posturography – assesses body sway on a moving platform.

Posturography – assesses body sway on a moving platform.

High-definition MRI provides the best structural imaging of the brainstem and CPA and is useful where a central cause of vertigo is suspected.

High-definition MRI provides the best structural imaging of the brainstem and CPA and is useful where a central cause of vertigo is suspected.

Vestibular neuronitis

Vestibular neuronitis is a common, poorly understood problem. It is an acute attack of isolated vertigo with nystagmus, often with vomiting, believed to follow viral infections. The disturbance lasts for several days or weeks, is self-limiting and rarely recurs. Vestibular neuronitis is sometimes followed by benign positional vertigo (p. 1071). Deafness is absent. Acute treatment is with vestibular sedatives. Similar symptoms can be caused by MS or brainstem vascular lesions. Other signs are usually apparent.

Lower cranial nerves IX, X, XI, XII

IXth and Xth nerve lesions

Principal causes of IXth, Xth, XIth and XIIth nerve lesions are listed in Box 22.7.

Bulbar and pseudobulbar palsy

Bulbar palsy

This is LMN weakness of muscles whose cranial nerve nuclei lie in the medulla (the bulb). Paralysis of bulbar muscles is caused by disease of lower cranial nerve nuclei, lesions of IXth, Xth and XIIth nerves (Box 22.7), malfunction of their neuromuscular junctions (e.g. myasthenia gravis, botulism) or disease of muscles themselves (e.g. dystrophies).

Pseudobulbar palsy

Motor neurone disease – often both UMN and LMN lesions (i.e. elements of both pseudobulbar and bulbar palsy)

Motor neurone disease – often both UMN and LMN lesions (i.e. elements of both pseudobulbar and bulbar palsy)

Cerebrovascular disease, typically following multiple infarcts

Cerebrovascular disease, typically following multiple infarcts

Neurodegenerative disorders such as progressive supranuclear palsy (p. 1120)

Neurodegenerative disorders such as progressive supranuclear palsy (p. 1120)

Difficulty swallowing, dysarthria and drooling also develop in later stages of Parkinson’s disease.

Motor control systems

The corticospinal (or pyramidal) system enables purposive, skilled, intricate, strong and organized movements. Defective function is recognized by a distinct pattern of signs – loss of skilled voluntary movement, spasticity and reflex change – seen, e.g. in a hemiparesis, hemiplegia or paraparesis.

The corticospinal (or pyramidal) system enables purposive, skilled, intricate, strong and organized movements. Defective function is recognized by a distinct pattern of signs – loss of skilled voluntary movement, spasticity and reflex change – seen, e.g. in a hemiparesis, hemiplegia or paraparesis.

The extrapyramidal system facilitates fast, fluid movements that the corticospinal system has generated. Defective function produces slowness (bradykinesia), stiffness (rigidity) and/or disorders of movement (rest tremor, chorea and other dyskinesias). One feature (e.g. stiffness, tremor or chorea) will often predominate.

The extrapyramidal system facilitates fast, fluid movements that the corticospinal system has generated. Defective function produces slowness (bradykinesia), stiffness (rigidity) and/or disorders of movement (rest tremor, chorea and other dyskinesias). One feature (e.g. stiffness, tremor or chorea) will often predominate.

The cerebellum and its connections have a role coordinating smooth and learned movement, initiated by the pyramidal system, and in posture and balance control. Cerebellar disease leads to unsteady and jerky movements (ataxia), with characteristic limb signs of past pointing, action tremor and incoordination, gait ataxia and/or truncal ataxia.

The cerebellum and its connections have a role coordinating smooth and learned movement, initiated by the pyramidal system, and in posture and balance control. Cerebellar disease leads to unsteady and jerky movements (ataxia), with characteristic limb signs of past pointing, action tremor and incoordination, gait ataxia and/or truncal ataxia.

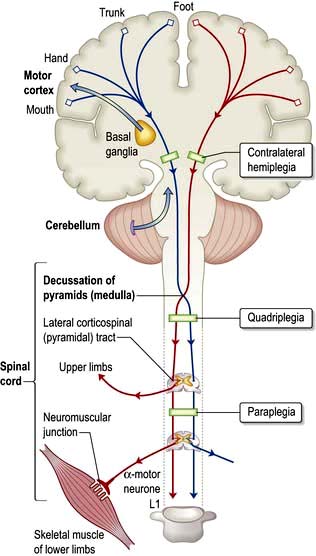

Corticospinal (pyramidal) system

The corticospinal tracts originate in neurones of the cortex and terminate at motor nuclei of cranial nerves and spinal cord anterior horn cells. The pathways of particular clinical significance (Fig. 22.9) congregate in the internal capsule and cross in the medulla (decussation of the pyramids), passing to the contralateral cord as the lateral corticospinal tracts. This is the pyramidal system, disease of which causes upper motor neurone (UMN) lesions. ‘Pyramidal’ is simply a descriptive term that draws together anatomy and characteristic physical signs, and is used interchangeably with the term UMN.

Characteristics of pyramidal lesions (Box 22.8)

Patterns of UMN disorders

There are three main patterns:

Hemiparesis means weakness of the limbs on one side; it is usually caused by a lesion in the brain and occasionally in the cord.

Hemiparesis means weakness of the limbs on one side; it is usually caused by a lesion in the brain and occasionally in the cord.

Paraparesis means weakness of both lower limbs and is usually diagnostic of a cord lesion; bilateral brain lesions occasionally cause paraparesis.

Paraparesis means weakness of both lower limbs and is usually diagnostic of a cord lesion; bilateral brain lesions occasionally cause paraparesis.

Tetraparesis (syn. quadriparesis) means weakness of four limbs.

Tetraparesis (syn. quadriparesis) means weakness of four limbs.

Hemiparesis

The level within the corticospinal system is recognized by particular features.

Internal capsule. Corticospinal fibres are tightly packed in the internal capsule (about 1 cm2), thus a small lesion causes a large deficit. A middle cerebral artery branch infarction (p. 1100) produces a sudden, dense, contralateral hemiplegia.

Pons. A pontine lesion (e.g. an MS plaque) is rarely confined to the corticospinal tract. Adjacent structures, e.g. VIth and VIIth nuclei, MLF and PPRF (p. 1075) are involved – diplopia, facial weakness, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) and/or a lateral gaze palsy occur with contralateral hemiparesis.

Spinal cord. An isolated lesion of one lateral corticospinal tract (e.g. a cervical cord injury) causes an ipsilateral UMN lesion, the level indicated by changes in reflexes (e.g. absent biceps, C5/6), features of a Brown–Séquard syndrome (p. 1086) and muscle wasting at the level of the lesion (p. 1087).

Spastic paraparesis

Paraparesis indicates bilateral damage to corticospinal pathways causing weakness and spasticity (or flaccid weakness in the initial phase of spinal shock after an acute cord insult). Cord compression (p. 1135) or cord diseases are the usual causes; cerebral lesions occasionally produce paraparesis. Paraparesis is a feature of many neurological conditions; finding the cause is crucial (p. 1135).

Extrapyramidal system

Reduction in speed (bradykinesia, meaning slow movement) or akinesia (no movement), with muscle rigidity

Reduction in speed (bradykinesia, meaning slow movement) or akinesia (no movement), with muscle rigidity

Involuntary movements (e.g. tremor, chorea, hemiballismus, athetosis, dystonia).

Involuntary movements (e.g. tremor, chorea, hemiballismus, athetosis, dystonia).

Extrapyramidal disorders are classified broadly into akinetic-rigid syndromes (p. 1130) where poverty of movement predominates, and dyskinesias where there are involuntary movements (p. 1121).

The most common extrapyramidal disorder is Parkinson’s disease.

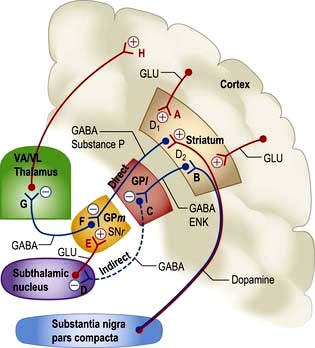

Essential anatomy

The corpus striatum lies close to the substantia nigra, thalami and subthalamic nuclei, lateral to the internal capsule (Figs 22.9, 22.10).

Function and dysfunction

Overall function of this system is modulation of cortical motor activity by a series of servo loops between cortex and basal ganglia (Fig. 22.10). In involuntary movement disorders there are specific changes in neurotransmitters (Table 22.5) rather than focal lesions seen on imaging or at autopsy.

Table 22.5 Changes in neurotransmitters in Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases

| Condition | Site | Neurotransmitter |

|---|---|---|

|

Parkinson’s |

Putamen

Substantia nigra Cerebral cortex |

Dopamine ↓ 90%Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) ↓ 60%5-HT ↓ 60%Dopamine ↓ 90%GAD + GABA ↓↓GAD + GABA ↓↓ |

|

Huntington’s |

Corpus striatum |

Acetylcholine ↓↓GABA ↓↓Dopamine: normalGAD + GABA ↓↓ |

GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing GABA; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

Proposed model of principal pathways

1. Direct pathway from striatum to medial globus pallidus (GPm) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). Inhibitory synapse F, GABA and substance P.

2. Indirect pathway from striatum to globus pallidus; via lateral globus pallidus (GPl; inhibitory synapse C, GABA, enkephalin) and subthalamic nucleus (inhibitory synapse D, GABA). Terminates in GPm-SNr (in excitatory synapse E, glutamate).

3. Direct pathways, both inhibitory and excitatory from substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) to striatum. Synapse A, dopamine, D1, excitatory; and synapse B, D2, inhibitory.

4. GPm and SNr to thalamus. Inhibitory synapse G, GABA.

Parkinson’s disease (PD). This is characterized by slowness, stiffness and rest tremor (p. 1118). Degeneration in SNc causes loss of dopamine activity in the striatum. Dopamine is excitatory for synapse A and inhibitory for synapse B. Through the direct pathway there is reduced activity at synapse F, leading to increased inhibitory output (G) and decreased cortical activity (H).

Levodopa helps slowness and tremor in PD (p. 1119) but induces unwanted dyskinesias by increasing dopamine activity at synapses A and B, it is thought by reversing sequences in both direct and indirect pathways.

Hemiballismus (p. 1121). Wild, flinging (ballistic) limb movements are caused by a lesion in the subthalamic nucleus, typically an infarct. This reduces excitatory activity at synapse E, reduces inhibition at G, with increased thalamo-cortical neuronal activity, and increases activity at H.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum receives afferents from:

Efferents pass from the cerebellum to:

Cerebellar lesions (Box 22.9)

Expanding lesions obstruct the aqueduct to cause hydrocephalus, with severe pressure headaches, vomiting and papilloedema. Coning of the cerebellar tonsils (p. 1133) through the foramen magnum leads to respiratory arrest, sometimes within minutes/hours. Rarely, tonic seizures (attacks of limb stiffness) occur.

Lateral cerebellar hemisphere lesions

Nystagmus. Coarse horizontal nystagmus (p. 1075) develops with a lateral cerebellar lobe lesion. The fast component is always towards the side of the lesion.

Dysarthria. Halting, jerking speech develops – scanning speech.

Other signs. Titubation – rhythmic head tremor as either forward and back (yes-yes) movements or rotary (no-no) movements – can occur, mainly when cerebellar connections are involved (e.g. in essential tremor and MS, pp. 1080 and 1124). Hypotonia (floppy limbs) and depression of reflexes (with slow, pendular reflexes) are also sometimes seen.

Midline cerebellar lesions

Cerebellar vermis lesions have dramatic effects on trunk and axial muscles. There is difficulty standing and sitting unsupported (truncal ataxia), with a rolling, broad, ataxic gait. Lesions of the flocculonodular region cause vertigo and vomiting with gait ataxia if they extend to the roof of the IVth ventricle. Box 22.9 summarizes the main causes of cerebellar disease.

Tremor

Tremor means a regular and sinusoidal oscillation of the limbs, head or trunk.

Lower motor neurone (LMN) lesions

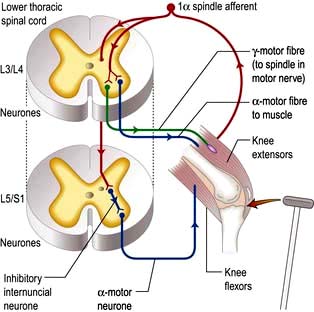

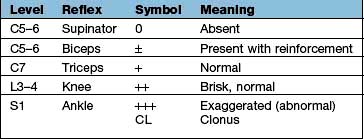

Spinal reflex arc

Components are illustrated in Figure 22.11. The stretch reflex is the physiological basis for all tendon reflexes. In the knee jerk, a tap on the patellar tendon activates stretch receptors in the quadriceps. Impulses in first-order sensory neurones pass directly to LMNs (L3 and L4) that contract quadriceps. Loss of a tendon reflex is caused by a lesion anywhere along the spinal reflex path. The reflex lost indicates its level (Table 22.6).

Sensory pathways and pain

Peripheral nerves and spinal roots

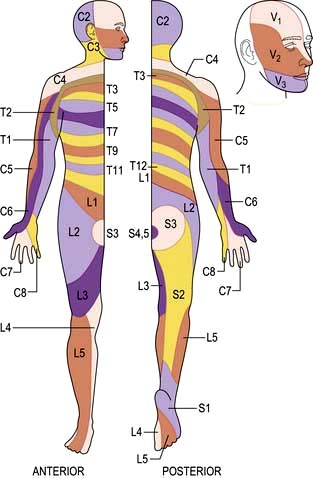

Peripheral nerves carry all modalities of sensation from either free or specialized nerve endings to dorsal roots and thence to the cord. Sensory distribution of spinal roots (dermatomes) is shown in Figure 22.12.

Spinal cord

Posterior columns

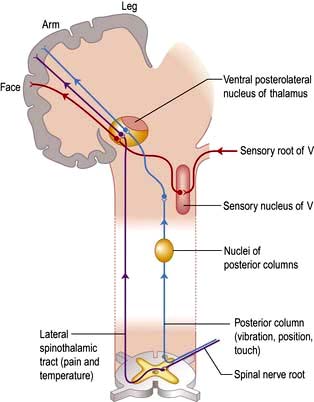

Axons in the posterior columns whose cell bodies are in the ipsilateral gracile and cuneate nuclei in the medulla carry sensory modalities of vibration, joint position (proprioception), light touch and two-point discrimination. Axons from second-order neurones then cross in the brainstem to form the medial lemniscus, passing to the thalamus (Fig. 22.13).

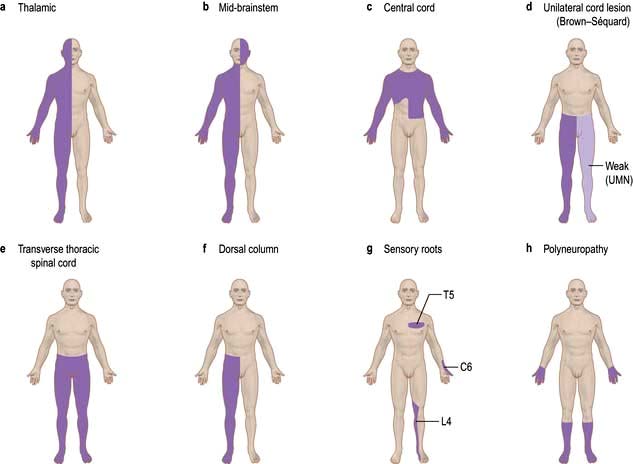

Lesions of the sensory pathways

Altered sensation (paraesthesia), tingling, clumsiness, numbness and pain are the principal symptoms of sensory lesions. The pattern and distribution point to the site of pathology (Fig. 22.14).

Peripheral nerve lesions

Symptoms are felt within the distribution of a peripheral nerve (p. 1143). Section of a sensory nerve is followed by complete sensory loss. Nerve entrapment (p. 1144) causes numbness, pain and tingling. Tapping the site of compression sometimes causes a sharp, electric-shock-like pain in the distribution of the nerve, known as Tinel’s sign, e.g. in carpal tunnel syndrome (p. 1144).

Spinal root lesions

Root pain

Pain of root compression is felt in the myotome supplied by the root, and there is also a tingling discomfort in the dermatome. The pain is worsened by manoeuvres that either stretch the root (e.g. straight leg raising in lumbar disc prolapse) or increase pressure in the spinal subarachnoid space (coughing and straining). Cervical and lumbar disc protrusions (p. 1148) are common causes of root lesions.

Spinal cord lesions

Posterior column lesions

These symptoms, though lateralized, are often felt vaguely without a clear sensory level. Position sense, vibration sense, light touch and two-point discrimination are diminished below the lesion. Position sense loss produces a stamping gait (sensory ataxia, p. 1068).

Lhermitte’s phenomenon

Electric-shock-like sensations radiate down the trunk and limbs on neck flexion. This points to a cervical cord lesion. Lhermitte’s is common in acute exacerbations of MS (p. 1124), and also occurs in cervical myelopathy (p. 1149), subacute combined degeneration of the cord (p. 1147), radiation myelopathy (p. 1149) and cord compression.

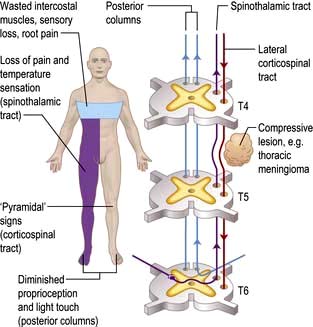

Spinothalamic tract lesions

Pure spinothalamic spinal lesions cause contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation with a clear level below the lesion. This is called dissociated sensory loss – pain and temperature are dissociated from light touch, which remains preserved. This is seen typically in syringomyelia where a cavity occupies the central cord (p. 1137).

The spinal level is modified by lamination of fibres within the spinothalamic tracts. Fibres from lower spinal roots lie superficially and are damaged first by compressive lesions from outside the cord. As an external compressive lesion (e.g. a midthoracic extradural meningioma; Fig. 22.15) enlarges, the spinal sensory level ascends as deeper fibres become involved. Conversely, a central cord lesion (e.g. a syrinx, p. 1137) affects deeper fibres first. Spinothalamic tract lesions cause loss of pain and temperature perception (e.g. painless burns). Perforating ulcers and neuropathic (Charcot) joints develop.

Spinal cord compression (Fig. 22.15)

Damage to one spinothalamic tract (contralateral loss of pain and temperature) with the ipsilateral corticospinal tract is known as the Brown-Séquard syndrome (originally, cord hemisection). The patient complains of numbness on one side and weakness on the other. Paraparesis/spinal cord lesions are discussed on page 1135.

Pontine lesions

Since lesions (e.g. an MS plaque) lie above the decussation of the posterior columns, and both medial lemniscus and spinothalamic tracts are close together, there is loss of all forms of sensation on the side opposite the lesion. Combinations of III, IV, V, VI and VII cranial nerve nuclei are seen, and may indicate a level (Fig. 22.13).

Parietal cortex lesions

Sensory loss, neglect of one side, apraxia (p. 1068) and subtle disorders of sensation occur. Pain is not a feature of destructive cortical lesions. Irritative phenomena (e.g. partial sensory seizures from a parietal cortex glioma) cause tingling sensations in a limb, or elsewhere.

Pain

Essential physiology of pain

Endogenous opiates

FURTHER READING

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management. Anaesthesiology 2010; 112:810–833.

Turk DC, Wilson HD, Cahana A. Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Lancet 2011; 377:2226–2235.

Management of chronic pain

Chronic pain is gravely disabling, distressing, and taxing to treat (p. 509). Multidisciplinary pain-relief clinics provide specific and supportive therapy.

Management plans for intractable pain have seven components:

Psychological

Chronic pain influences quality of life. Depression (p. 1170) is commonly associated with pain when the pathology is benign; antidepressants can help. Of patients suffering pain from secondary cancer about one-third are clinically depressed.

Analgesics

Perseverance and compliance with therapy is a common problem. The WHO analgesic ladder (p. 487) is useful.

Co-analgesics

Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline

Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline

Duloxetine – a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake blocker

Duloxetine – a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake blocker

Anticonvulsants, e.g. carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin (p. 486)

Anticonvulsants, e.g. carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin (p. 486)

Calcium-channel blockers, e.g. ziconotide used intrathecally in chronic refractory pain

Calcium-channel blockers, e.g. ziconotide used intrathecally in chronic refractory pain

Capsaicin topical preparations – extracts from capsicum plants (chilli peppers) which bind to vanilloid receptors on pain neurones and deplete them of neurotransmitters such as substance P.

Capsaicin topical preparations – extracts from capsicum plants (chilli peppers) which bind to vanilloid receptors on pain neurones and deplete them of neurotransmitters such as substance P.

Bladder control and sexual dysfunction

Essential functions and anatomy

The bladder has two functions: storage and voiding. Afferent pathways (T12–S4) respond to pressure within the bladder and sensation from the genitalia. As the bladder distends, continence is maintained by suppression of parasympathetic and reciprocal activation of sympathetic outflow. Both are under some voluntary control. Voiding takes place by para-sympathetic activation of the detrusor, and relaxation of the internal sphincter (Table 22.7).

| Nerve supply | Function |

|---|---|

|

Parasympathetic |

Bladder wall: contraction |

|

S2–4 |

Internal sphincter: relaxationPenis/clitoris: engorgement |

|

Sympathetic |

Bladder wall: relaxation |

|

T12–L2 |

Internal sphincter: contractionOrgasm, ejaculation |

|

Pudendal nerves |

External sphincter (skeletal muscle) |

Neurological disorders of micturition

Post-central lesions cause loss of sense of bladder fullness

Post-central lesions cause loss of sense of bladder fullness

LMN. Sacral lesions (conus medullaris, sacral root and pelvic nerve – bilateral) cause a flaccid, atonic bladder that overflows (cauda equina, p. 1149), often unexpectedly.

Neurological tests

Neuro-imaging

Skull and spinal X-rays

Fractures of the vault or base

Fractures of the vault or base

Vault and skull base disease (e.g. metastases, osteomyelitis, Paget’s disease, abnormal skull foramina, fibrous dysplasia)

Vault and skull base disease (e.g. metastases, osteomyelitis, Paget’s disease, abnormal skull foramina, fibrous dysplasia)

Enlargement or destruction of the pituitary fossa-intrasellar tumour, raised intracranial pressure

Enlargement or destruction of the pituitary fossa-intrasellar tumour, raised intracranial pressure

Intracranial calcification – tuberculoma, oligodendroglioma, wall of an aneurysm, cysticercosis.

Intracranial calcification – tuberculoma, oligodendroglioma, wall of an aneurysm, cysticercosis.

Brain computed tomography (CT)

Enhancement with i.v. contrast delineates areas of altered blood supply (CT angiography).

Safety. The irradiation involved is relatively small. There are occasional reactions to contrast.

Limitations of brain CT

Lesions under 1 cm in diameter may be missed.

Lesions under 1 cm in diameter may be missed.

Lesions with attenuation close to bone may be missed, if near the skull.

Lesions with attenuation close to bone may be missed, if near the skull.

Lesions with attenuation similar to brain are poorly displayed (e.g. MS plaques, isodense subdural haematoma).

Lesions with attenuation similar to brain are poorly displayed (e.g. MS plaques, isodense subdural haematoma).

CT is not good at detecting posterior fossa lesions because of surrounding bone.

CT is not good at detecting posterior fossa lesions because of surrounding bone.

Patient cooperation: an anaesthetic is very occasionally needed.

Patient cooperation: an anaesthetic is very occasionally needed.

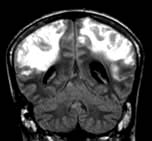

Magnetic resonance imaging: MRI

Advantages of MRI

MR distinguishes between white and grey matter in the brain and cord.

MR distinguishes between white and grey matter in the brain and cord.

Cord and nerve roots are imaged directly.

Cord and nerve roots are imaged directly.

MRI has resolution superior to CT (around 0.5 cm).

MRI has resolution superior to CT (around 0.5 cm).

MR angiography (MRA) images blood vessels without contrast.

MR angiography (MRA) images blood vessels without contrast.

Tumours, infarction, haemorrhage, MS plaques, posterior fossa, foramen magnum and cord are demonstrated well by MRI.

Tumours, infarction, haemorrhage, MS plaques, posterior fossa, foramen magnum and cord are demonstrated well by MRI.

Limitations are principally time and cost. Patients need to keep still within a narrow tube: claustrophobia is an issue; open machines are available that are less claustrophobic. Patients with pacemakers or metallic fragments in the brain cannot be imaged. MR imaging frequently shows diffuse meningeal enhancement with gadolinium for some days after lumbar puncture (p. 1091).

Positron emission tomography (PET), single proton emission computed tomography (SPECT), dopamine transporter imaging (DAT) and functional MRI (fMRI)

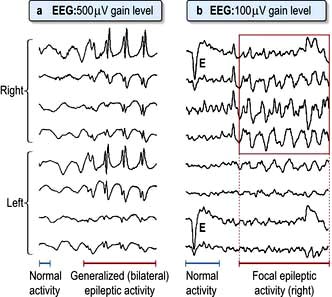

Electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG (Fig. 22.16) recorded from scalp electrodes (16 channels simultaneously) is of value in epilepsy and diffuse brain diseases. Videotelemetry, combining EEG with video, is invaluable in attacks difficult to diagnose.

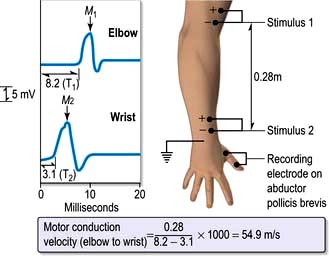

Electromyography and conduction studies

Cerebral-evoked potentials

Visual-evoked potentials (VEPs) record the interval visual stimuli take to reach the occipital cortex, and the amplitude of response. VEPs are used to confirm previous retrobulbar neuritis (p. 1073); this leaves a delayed latency despite clinical recovery.

Similar techniques for auditory and somatosensory potentials (from a limb) are also used.

Lumbar puncture and CSF examination

| Appearance | Crystal clear, colourless |

|---|---|

|

Pressure |

60–150 mm of CSF, recumbent |

|

Cell count |

<5/mm3No polymorphsMononuclear cells only |

|

Protein |

0.2–0.4 g/L |

|

Glucose |

– – of blood glucose of blood glucose |

|

IgG |

<15% of total CSF protein |

|

Oligoclonal bands |

Absent |

![]() Practical Box 22.3

Practical Box 22.3

Lumbar puncture

Technique

The patient is placed on the edge of the bed in the left lateral position with knees and chin as close together as possible.

The patient is placed on the edge of the bed in the left lateral position with knees and chin as close together as possible.

The third and fourth lumbar spines are marked. The fourth lumbar spine usually lies on a line joining the iliac crests.

The third and fourth lumbar spines are marked. The fourth lumbar spine usually lies on a line joining the iliac crests.

Using sterile precautions, 2% lidocaine is injected into the dermis by raising a bleb in either the third or fourth lumbar interspace.

Using sterile precautions, 2% lidocaine is injected into the dermis by raising a bleb in either the third or fourth lumbar interspace.

The LP needle is pushed through the skin in the midline, steadily forwards and slightly towards the head, with the head and spine bolstered horizontally with pillows.

The LP needle is pushed through the skin in the midline, steadily forwards and slightly towards the head, with the head and spine bolstered horizontally with pillows.

When the needle is felt to penetrate the dura, the stylet is withdrawn and a few drops of CSF allowed to escape.

When the needle is felt to penetrate the dura, the stylet is withdrawn and a few drops of CSF allowed to escape.

The CSF pressure can then be measured with a manometer connected to the needle. The patient’s head must be on the same level as the sacrum. Normal CSF pressure is 60–150 mm of CSF. The level rises and falls with respiration and heart beat, and rises on coughing.

The CSF pressure can then be measured with a manometer connected to the needle. The patient’s head must be on the same level as the sacrum. Normal CSF pressure is 60–150 mm of CSF. The level rises and falls with respiration and heart beat, and rises on coughing.

CSF specimens are collected in three sterile bottles and a sample for CSF glucose, together with a simultaneous blood glucose sample.

CSF specimens are collected in three sterile bottles and a sample for CSF glucose, together with a simultaneous blood glucose sample.

Record CSF naked-eye appearance: clear, cloudy, yellow (xanthochromic), red.

Record CSF naked-eye appearance: clear, cloudy, yellow (xanthochromic), red.

The patient is asked to lie flat after the procedure to avoid subsequent headaches, but this manoeuvre is probably of little value.

The patient is asked to lie flat after the procedure to avoid subsequent headaches, but this manoeuvre is probably of little value.

Contraindications

Suspicion of a mass lesion in the brain or cord. Caudal herniation of the cerebellar tonsils (coning) may occur if an intracranial mass is present and the pressure below is reduced by removal of CSF

Suspicion of a mass lesion in the brain or cord. Caudal herniation of the cerebellar tonsils (coning) may occur if an intracranial mass is present and the pressure below is reduced by removal of CSF

Any cause of raised intracranial pressure

Any cause of raised intracranial pressure

Local infection near the LP site

Local infection near the LP site

Congenital lesions in the lumbosacral region (e.g. meningomyelocele)

Congenital lesions in the lumbosacral region (e.g. meningomyelocele)

Platelet count <40 × 109/L and other clotting abnormalities, including anticoagulant drugs

Platelet count <40 × 109/L and other clotting abnormalities, including anticoagulant drugs

Unconscious patients and those with papilloedema must have a CT scan before lumbar puncture.

Unconscious patients and those with papilloedema must have a CT scan before lumbar puncture.

Indications for lumbar puncture (LP):

Diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis

Diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis

Diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage (sometimes)

Diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage (sometimes)

Measurement of CSF pressure, e.g. idiopathic intracranial hypertension (p. 1110)

Measurement of CSF pressure, e.g. idiopathic intracranial hypertension (p. 1110)

Removal of CSF therapeutically, e.g. idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Removal of CSF therapeutically, e.g. idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Diagnosis of various conditions, e.g. MS, neurosyphilis, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s, neoplastic involvement, polyneuropathies

Diagnosis of various conditions, e.g. MS, neurosyphilis, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s, neoplastic involvement, polyneuropathies

Biopsy

Routine tests

| Test | Yield | Condition |

|---|---|---|

|

Urinalysis |

Glycosuria |

Polyneuropathy |

|

Ketones |

Coma |

|

|

Bence Jones protein |

Cord compression |

|

|

Blood picture |

↑ T MCV↑↑ T T ESR |

B12 deficiencyGiant cell arteritis |

|

Blood glucose |

HypoglycaemiaHyperglycaemia |

ComaComa |

|

Serum electrolytes |

Hyponatraemia |

Coma |

|

Hypokalaemia |

Weakness |

|

|

Serum calcium |

Hypocalcaemia |

Tetany, spasms |

|

Serum CPK |

Raised |

Muscle disease |

|

Chest X-ray |

Lytic bone or mass lesion |

Bronchial cancer, thymoma |

Specialized tests in specific diseases

Various tests are employed to diagnose individual (sometimes rare) diseases. Examples are:

Anti-cardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant antibody and detailed clotting studies in stroke (p. 538)

Anti-cardiolipin and lupus anticoagulant antibody and detailed clotting studies in stroke (p. 538)

Antibody to acetylcholine receptor protein and anti-Mu SK antibodies in myasthenia gravis (p. 1151)

Antibody to acetylcholine receptor protein and anti-Mu SK antibodies in myasthenia gravis (p. 1151)

Serum copper and caeruloplasmin in Wilson’s disease (p. 1098)

Serum copper and caeruloplasmin in Wilson’s disease (p. 1098)

Blood lactate studies (failure to rise on exercise) in McArdle’s syndrome (p. 1069)

Blood lactate studies (failure to rise on exercise) in McArdle’s syndrome (p. 1069)

Anti-neuronal antibodies (paraneoplastic syndromes)

Anti-neuronal antibodies (paraneoplastic syndromes)

Serum phytanic acid (elevated) in Refsum’s disease

Serum phytanic acid (elevated) in Refsum’s disease

Serum long-chain fatty acid (present) in adrenoleucodystrophy

Serum long-chain fatty acid (present) in adrenoleucodystrophy

Genetic studies, e.g. Huntington’s disease, hereditary sensorimotor neuropathies and ataxias (p. 1121 and p. 1147).

Genetic studies, e.g. Huntington’s disease, hereditary sensorimotor neuropathies and ataxias (p. 1121 and p. 1147).

Unconsciousness and coma

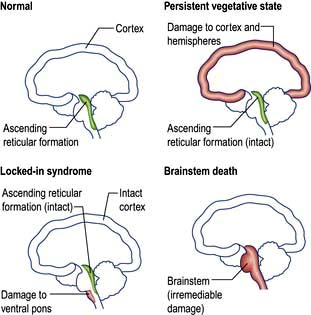

Consciousness is dependent on the functioning of two separate anatomical and physiological systems:

The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) projecting from brainstem to thalamus. This determines arousal (the level of consciousness)

The ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) projecting from brainstem to thalamus. This determines arousal (the level of consciousness)

The cerebral cortex, which determines the content of consciousness.

The cerebral cortex, which determines the content of consciousness.

Impaired functioning of either anatomical system may cause coma.

Disturbed consciousness: definitions

Coma: a state of unrousable unresponsiveness. Level of consciousness represents a continuum between being alert and deeply comatose. It may be quantified using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) with a score between 3 and 15 (Table 22.10). Coma may be conveniently defined as a GCS of 8 or lower. Terms such as stupor and obtundation have been superseded by the GCS score and are no longer used.

Coma: a state of unrousable unresponsiveness. Level of consciousness represents a continuum between being alert and deeply comatose. It may be quantified using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) with a score between 3 and 15 (Table 22.10). Coma may be conveniently defined as a GCS of 8 or lower. Terms such as stupor and obtundation have been superseded by the GCS score and are no longer used.

Delirium: The term used to describe a confusional state in which reduced attention is a cardinal feature, usually with altered behaviour, cognition, orientation and a fluctuating level of consciousness (from agitation to hypoarousal) (see p. 1187).

Delirium: The term used to describe a confusional state in which reduced attention is a cardinal feature, usually with altered behaviour, cognition, orientation and a fluctuating level of consciousness (from agitation to hypoarousal) (see p. 1187).

| Score | |

|---|---|

|

Eye opening (E) |

|

|

Spontaneous To speech To pain No response |

4321 |

|

Motor response (M) |

|

|

Obeys Localizes Withdraws Flexion Extension No response |

654321 |

|

Verbal response (V) |

|

|

Orientated Confused conversation Inappropriate words Incomprehensible sounds No response |

54321 |

Glasgow Coma Scale = E + M + V (GCS minimum = 3; maximum = 15).

Mechanisms and causes of coma (Box 22.11)

Altered consciousness is produced by four mechanisms affecting the ARAS in the brainstem or thalamus, and/or widespread impairment of cortical function (Fig. 22.18).

Brainstem lesion. A discrete brainstem or thalamic lesion, e.g. stroke may damage the ARAS.

Brainstem lesion. A discrete brainstem or thalamic lesion, e.g. stroke may damage the ARAS.

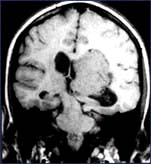

Brainstem compression. A supratentorial mass lesion within the brain compresses the brainstem, inhibiting the ARAS, e.g. ‘coning’ from a brain tumour or haemorrhage. Mass lesions within the posterior fossa are particularly prone to cause brainstem compression and hydrocephalus.

Brainstem compression. A supratentorial mass lesion within the brain compresses the brainstem, inhibiting the ARAS, e.g. ‘coning’ from a brain tumour or haemorrhage. Mass lesions within the posterior fossa are particularly prone to cause brainstem compression and hydrocephalus.

Diffuse brain dysfunction. Generalized severe metabolic or toxic disorders (e.g. alcohol, sedatives, uraemia, hypercapnia) depress cortical and ARAS function.

Diffuse brain dysfunction. Generalized severe metabolic or toxic disorders (e.g. alcohol, sedatives, uraemia, hypercapnia) depress cortical and ARAS function.

Massive cortical damage. Unlike brainstem lesions, extensive damage of the cerebral cortex and cortical connections is required to cause coma, e.g. meningitis or hypoxic-ischaemic damage after cardiac arrest (see Fig. 22.19).

Massive cortical damage. Unlike brainstem lesions, extensive damage of the cerebral cortex and cortical connections is required to cause coma, e.g. meningitis or hypoxic-ischaemic damage after cardiac arrest (see Fig. 22.19).

![]() Box 22.11

Box 22.11

Principal causes of coma – examples of mechanisms

Diffuse brain dysfunction

Drug overdose (accidental or deliberate), including alcohol

Drug overdose (accidental or deliberate), including alcohol

Hepatic encephalopathy (p. 336)

Hepatic encephalopathy (p. 336)

Respiratory failure with CO2 retention (p. 814)

Respiratory failure with CO2 retention (p. 814)

Hypoadrenalism, hypopituitarism and hypothyroidism

Hypoadrenalism, hypopituitarism and hypothyroidism

Seizures – post-ictal state and non-convulsive status

Seizures – post-ictal state and non-convulsive status

Metabolic rarities, e.g. porphyria

Metabolic rarities, e.g. porphyria

Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury, e.g. cardiac arrest

Hypoxic-ischaemic brain injury, e.g. cardiac arrest

Figure 22.18 Anatomy of vegetative state, locked-in syndrome and brainstem death.

(Adapted from Bates D. Coma and brainstem death. Medicine 2004; 32, with permission of Elsevier.)

The unconscious patient

Immediate assessment and management

Check the airway, breathing and circulation.

Check the airway, breathing and circulation.

Stix for blood glucose; if hypoglycaemic give glucose (25 mL 50%).

Stix for blood glucose; if hypoglycaemic give glucose (25 mL 50%).

Treat seizures with buccal midazolam and if not terminated, intravenous phenytoin.

Treat seizures with buccal midazolam and if not terminated, intravenous phenytoin.

If there is fever and meningism, give intravenous antibiotics.

If there is fever and meningism, give intravenous antibiotics.

Intravenous naloxone or flumazenil (overdose) and thiamine (Wernicke’s encephalopathy) in people who use excess alcohol.

Intravenous naloxone or flumazenil (overdose) and thiamine (Wernicke’s encephalopathy) in people who use excess alcohol.

General and neurological examination

General examination (Fig. 22.20)

Measure the patient’s temperature (with a low reading rectal thermometer if hypothermic).Check for meningism.

Measure the patient’s temperature (with a low reading rectal thermometer if hypothermic).Check for meningism.

Sniff the patient’s breath for ketones, alcohol and hepatic fetor.

Sniff the patient’s breath for ketones, alcohol and hepatic fetor.

Survey the skin for signs of trauma or spinal injury, rash (meningococcal sepsis), jaundice or stigmata of chronic liver disease, cyanosis, injection marks.

Survey the skin for signs of trauma or spinal injury, rash (meningococcal sepsis), jaundice or stigmata of chronic liver disease, cyanosis, injection marks.

Neurological examination

Neurological examination aims to determine:

Brainstem function

Pupils

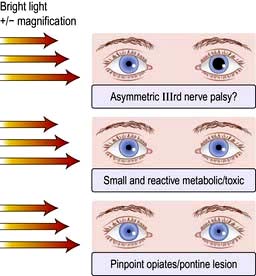

Record their size and reaction to light (Fig. 22.21):

Dilatation of one pupil that then becomes fixed to light indicates compression of the IIIrd nerve. This is a potential neurosurgical emergency (Fig. 22.22).

Dilatation of one pupil that then becomes fixed to light indicates compression of the IIIrd nerve. This is a potential neurosurgical emergency (Fig. 22.22).

Bilateral mid-point reactive pupils (i.e. normal pupils) are characteristic of metabolic comas and follow coma due to sedative drugs except opiates.

Bilateral mid-point reactive pupils (i.e. normal pupils) are characteristic of metabolic comas and follow coma due to sedative drugs except opiates.

Bilateral light-fixed, dilated pupils are one cardinal sign of brain death. They can occur in deep coma of any cause, but particularly in barbiturate intoxication and hypothermia.

Bilateral light-fixed, dilated pupils are one cardinal sign of brain death. They can occur in deep coma of any cause, but particularly in barbiturate intoxication and hypothermia.

Bilateral pinpoint, light-fixed pupils occur with pontine lesions (e.g. haemorrhage) and with opiates.

Bilateral pinpoint, light-fixed pupils occur with pontine lesions (e.g. haemorrhage) and with opiates.

Mydriatic drugs and previous pupillary surgery can cause diagnostic difficulty.

Mydriatic drugs and previous pupillary surgery can cause diagnostic difficulty.

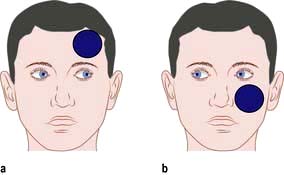

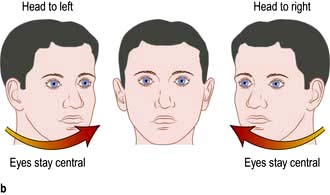

Eye movements and position

Dysconjugate eyes (divergent ocular axes) indicate a brainstem lesion, e.g. skew deviation (one eye up, one eye down; Fig. 22.23).

Dysconjugate eyes (divergent ocular axes) indicate a brainstem lesion, e.g. skew deviation (one eye up, one eye down; Fig. 22.23).

Conjugate gaze deviation – towards the lesion in the frontal lobe and the normal limbs (unopposed activity of the intact frontal eye fields drives eyes to the opposite side); away from the lesion in the brainstem and towards the weak limbs (the PPRF in the pons controls lateral gaze to the ipsilateral side – page 1075) (Fig. 22.24).

Conjugate gaze deviation – towards the lesion in the frontal lobe and the normal limbs (unopposed activity of the intact frontal eye fields drives eyes to the opposite side); away from the lesion in the brainstem and towards the weak limbs (the PPRF in the pons controls lateral gaze to the ipsilateral side – page 1075) (Fig. 22.24).

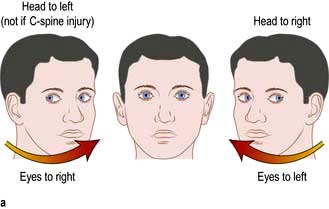

Vestibulo-ocular reflex. Passive head turning produces conjugate ocular deviation away from the direction of rotation (doll’s head reflex). This reflex disappears in deep coma, in brainstem lesions and in brain death (Fig. 22.25).

Vestibulo-ocular reflex. Passive head turning produces conjugate ocular deviation away from the direction of rotation (doll’s head reflex). This reflex disappears in deep coma, in brainstem lesions and in brain death (Fig. 22.25).

In light coma, slow, side-to-side eye movements are seen (‘windscreen wiper’ eyes Fig. 22.26). Also seen with extensive cortical damage in deep coma.

In light coma, slow, side-to-side eye movements are seen (‘windscreen wiper’ eyes Fig. 22.26). Also seen with extensive cortical damage in deep coma.

Lateralizing signs

Coma makes it difficult to recognize lateralizing signs. These are helpful:

Asymmetry of response to visual threat in a stuporose patient: suggests hemianopia

Asymmetry of response to visual threat in a stuporose patient: suggests hemianopia

Asymmetry of face. Drooping or dribbling on one side, blowing in and out of mouth when the paralysed cheek does not move

Asymmetry of face. Drooping or dribbling on one side, blowing in and out of mouth when the paralysed cheek does not move

Asymmetry of tone. Unilateral flaccidity or spasticity may be the only sign of hemiparesis

Asymmetry of tone. Unilateral flaccidity or spasticity may be the only sign of hemiparesis

Asymmetry of decerebrate and decorticate posturing

Asymmetry of decerebrate and decorticate posturing

Asymmetrical response to painful stimuli

Asymmetrical response to painful stimuli

Asymmetry of tendon reflexes and plantar responses. Both plantars are often extensor in deep coma.

Asymmetry of tendon reflexes and plantar responses. Both plantars are often extensor in deep coma.

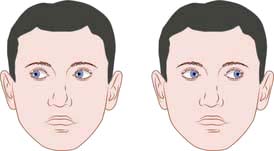

Coma ‘look-alikes’

‘Locked-in’ syndrome – complete paralysis except vertical eye movements/blinking in ventral pontine infarction. Patients have a functioning cerebral cortex and are fully aware but unable to communicate except through eye movements (Table 22.11).

‘Locked-in’ syndrome – complete paralysis except vertical eye movements/blinking in ventral pontine infarction. Patients have a functioning cerebral cortex and are fully aware but unable to communicate except through eye movements (Table 22.11).

Severe paralysis, e.g. myaesthenic crisis or severe Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Severe paralysis, e.g. myaesthenic crisis or severe Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Diagnosis and investigations in coma

Blood and urine

Drugs screen – blood alcohol and salicylates, urine toxicology including screening for benzodiazepines, narcotics, amphetamines

Drugs screen – blood alcohol and salicylates, urine toxicology including screening for benzodiazepines, narcotics, amphetamines

Biochemistry (urea, electrolytes, glucose, calcium, liver biochemistry)

Biochemistry (urea, electrolytes, glucose, calcium, liver biochemistry)

Metabolic and endocrine studies (TSH, cortisol)

Metabolic and endocrine studies (TSH, cortisol)

Arterial blood gases – for acidosis or high CO2 levels

Arterial blood gases – for acidosis or high CO2 levels

Other, e.g. cerebral malaria (request thick blood film) and porphyria (p. 1043).

Other, e.g. cerebral malaria (request thick blood film) and porphyria (p. 1043).

General management

Skin care – turning (to avoid pressure sores and pressure palsies)

Skin care – turning (to avoid pressure sores and pressure palsies)

Oral hygiene – mouthwashes, suction

Oral hygiene – mouthwashes, suction

Eye care – prevention of corneal damage (lid taping, irrigation)

Eye care – prevention of corneal damage (lid taping, irrigation)

Feeding – via a fine-bore nasogastric tube or via peg

Feeding – via a fine-bore nasogastric tube or via peg

Sphincters – catheterization when essential (use penile urinary sheath if possible in men); rectal evacuation.

Sphincters – catheterization when essential (use penile urinary sheath if possible in men); rectal evacuation.

Prognosis in coma and the vegetative state

The vegetative state (VS) is usually a consequence of extensive cortical damage. Brainstem function is intact so breathing is normal without the need for mechanical ventilation and the patient appears awake with eye opening and sleep–wake cycles. However there is no sign of awareness or response to environmental stimuli except reflex movements. Patients may remain in this state for years. It is considered permanent (PVS) if there is no recovery after 12 months where trauma is the cause and after 6 months for all other causes. Prolonged support of patients after this time presents a number of ethical issues – families may apply to the courts for withdrawal of feeding in PVS.

The vegetative state (VS) is usually a consequence of extensive cortical damage. Brainstem function is intact so breathing is normal without the need for mechanical ventilation and the patient appears awake with eye opening and sleep–wake cycles. However there is no sign of awareness or response to environmental stimuli except reflex movements. Patients may remain in this state for years. It is considered permanent (PVS) if there is no recovery after 12 months where trauma is the cause and after 6 months for all other causes. Prolonged support of patients after this time presents a number of ethical issues – families may apply to the courts for withdrawal of feeding in PVS.

Minimally conscious state (MCS) describes patients with some limited awareness, e.g. apparent, vague pain perception. A patient may emerge from VS into MCS. Distinguishing VS from MCS requires careful specialist assessment over a long period. Functional brain imaging has recently been used for this purpose.

Minimally conscious state (MCS) describes patients with some limited awareness, e.g. apparent, vague pain perception. A patient may emerge from VS into MCS. Distinguishing VS from MCS requires careful specialist assessment over a long period. Functional brain imaging has recently been used for this purpose.