17 Neurological disease

Approach to the patient

Imaging plays a key role in diagnosis.

Alterations in consciousness

| Category | Response | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Eye opening (E) | Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| Nil | 1 | |

| Speech/verbal response (V) | Appropriate and orientated | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| Nil | 1 | |

| Motor response (M) | Obeys commands appropriately | 6 |

| Localizes to pain | 5 | |

| Withdraws to pain | 4 | |

| Flexes to pain | 3 | |

| Extends to pain | 2 | |

| Nil | 1 |

GCS = E + V + M. Minimum score 3, maximum score 15.

Coma is a life-threatening emergency. Assessment must be swift and comprehensive, and occur in tandem with life support measures and initial investigations (Box 17.1, p. 624, and see Fig. 20.21 (p. 722)).

Box 17.1 Management of the comatose patient

This is a neurological emergency (see also Fig. 20.21). Enlist the help of an experienced nurse. The immediate priority is cardiorespiratory resuscitation.

Initial assessment

Investigations where cause of coma is unknown after initial assessment

Acute confusional state (delirium)

Delirium is characterized by abnormalities of perception and cognition, often without a decrease in the level of consciousness. Impairment in consciousness, if present, can vary and fluctuates with confusion, usually being worse at night. It is very common, especially in elderly hospitalized patients. There are a wide variety of causes, often occurring in combination, in a patient vulnerable by virtue of age or impaired cognitive reserve. Common causes include systemic infection, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalance, liver or renal failure, and drug/alcohol intoxication or withdrawal (especially anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, opiates), as well as brain injury, encephalitis/meningitis or deficiency states such as Wernicke–Korsakoff encephalopathy.

Management

Delirium tremens (DTs)

This is the most serious alcohol withdrawal state and occurs 1–3 days after alcohol cessation. Patients have disorientation, agitation, tremor and visual hallucinations. For treatment, see Box 17.2.

Stroke

![]() N.B. Stroke is a medical emergency and prompt treatment can improve prognosis.

N.B. Stroke is a medical emergency and prompt treatment can improve prognosis.

Pathophysiology

Clinical evaluation

• General physical examination

Stroke is primarily a clinical diagnosis, supported by imaging.

Immediate management (see Emergencies in Medicine p. 721)

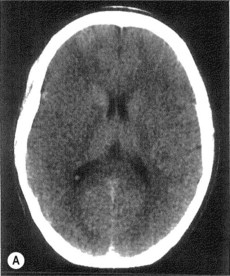

• Imaging in acute stroke

Thrombolysis (Box 17.3)

![]() N.B. Every minute counts. The benefit of thrombolysis decreases with time, even within the 4.5-hour window.

N.B. Every minute counts. The benefit of thrombolysis decreases with time, even within the 4.5-hour window.

Further management

• Secondary prevention

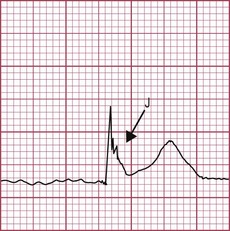

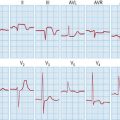

• Identification of embolic source

Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs)

| •Age > 60 years | 1 point |

| •BP > 140 mmHg systolic and/or > 90 mmHg diastolic | 1 point |

| •Clinical features | |

| Unilateral weakness | 2 points |

| Isolated speech disturbance | 1 point |

| Other | 0 points |

| •Duration of symptoms (mins) | |

| > 60 | 2 points |

| 10–59 | 1 point |

| < 10 | 0 points |

| •Diabetes | |

| Present | 1 point |

| Absent | 0 points |

Intracerebral haemorrhage

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)

Management

Subdural haemorrhage

Conservative management may be appropriate in older patients without neurological deficit.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a predisposition to recurrent seizures. Seizures are classified as:

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of epilepsy is predominantly clinical, but determining whether an episode of apparent loss of consciousness is due to epilepsy can be difficult. The main distinction is from syncope (p. 385). Witness descriptions or video recordings of the event are invaluable. Ask the patient and the witness what happened before, during and after the event. Ask about risk factors for epilepsy (e.g. family history, birth and developmental history, febrile convulsions in childhood, previous meningitis or encephalitis, significant head injury), arrhythmias and diabetes. Also enquire about drug use and alcohol excess.

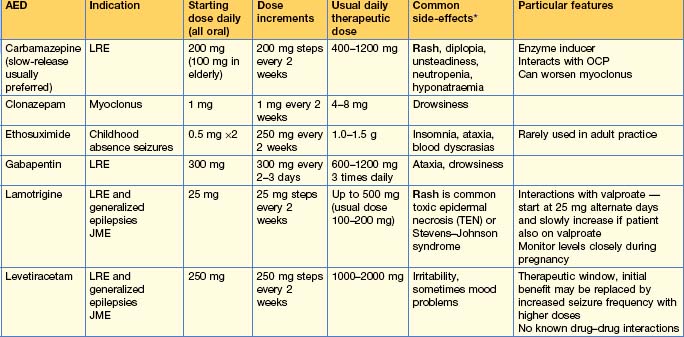

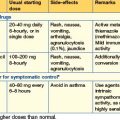

Use of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) (Table 17.2)

Withdrawal of AEDs

If the patient is taking multiple AEDs, withdraw only one drug at a time.

EEG prior to or during drug reduction can be helpful in predicting seizure recurrence.

Advise patients not to drive during periods of drug reduction and for 6 months after reduction/withdrawal is completed. If they have a seizure during drug alteration the Driving Licence Authority regulations will apply.

Status epilepticus (SE)

Acute management

Box 17.4 Status epilepticus management

Several treatment schedules exist

Movement disorders

Movement disorders may be divided into:

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD)

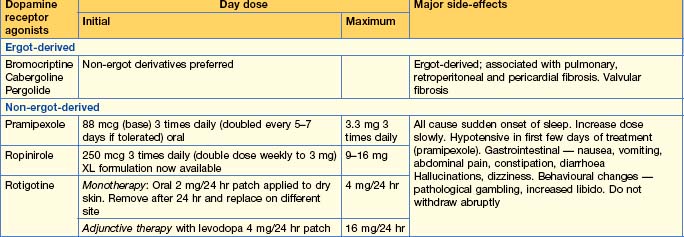

Medical treatment (Table 17.3)

Other drugs used to treat PD

Hyperkinetic movement disorders

Dystonia

Dystonia is painless muscle spasms causing twisting movements and abnormal postures. Childhood-onset dystonia is often genetic or due to a structural brain abnormality (e.g. birth asphyxia) and is more likely to become generalized. Late-onset dystonia is commoner, usually sporadic and more likely to remain localized to one body part, particularly the cranio-cervical region, e.g. blepharospasm or torticollis. Task-specific forms may occur, e.g. writer’s cramp or occupational dystonias, especially in musicians. Treatment of focal dystonia is by IM injection of botulinum toxin. Duration of effect is approximately 3 months.

Headache

Acute single episode of headache

If the headache is associated with drowsiness or neck stiffness, meningitis (p. 54), encephalitis (p. 55) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (p. 634) must be excluded. Sudden-onset thunderclap headache is suggestive of SAH. The incidence of serious secondary causes of headache is higher in A&E attenders than in general practice.

Primary headache disorders

Migraine

Migraine is due to changes in the brainstem blood flow which cause release of vasoactive peptides leading to neurogenic inflammation which produces the pain. Migraine without aura is more common than migraine with aura (25%) and those who experience auras usually do not have aura before each attack. Aura occurs before the onset of the headache and should last no longer than 1 hour. Visual aura is more common than sensory aura or dysphasia. Weakness (hemiplegic migraine) is rare. Typically, aura consists of positive and negative symptoms (shimmering, bright lights, fragmented images with scotomas or other visual field defects such as hemianopia) and usually evolves, changing over minutes. Migraine aura without subsequent headache (acephalic migraine) may occur in older patients and be confused with TIA.

• Women and migraine

Cluster headache

Low-pressure headache

Facial pain

Trigeminal neuralgia

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

’Dizziness’ means different things to different people. True vertigo indicates an illusion of movement, typically spinning. The commonest cause is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, which may follow head injury or ear infection. The Hallpike test is diagnostic, with torsional nystagmus seen. The Epley particle repositioning manœuvre may be curative. Cawthorne–Cooksey exercises/vestibular rehabilitation are preferred to vestibular sedatives (http://www.dizziness-and-balance.com/disorders/bppv/bppv.html; www.dizziness-and-balance.com/treatment/rehab/caw thorne.html).

Traumatic brain injury

Severe head injury

Immediate management

CT scanning is also required if the patient is > 65 years old or on anticoagulants, or if there was a dangerous mechanism of injury. Head injury is often associated with trauma to the cervical spine. Imaging of the cervical spine is essential to exclude fracture or dislocation.

Further management

Late complications

Late complications following significant traumatic brain injury include incomplete recovery (hemiparesis, cognitive impairment), post-traumatic epilepsy, depression, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, chronic subdural haematoma (p. 635), hydrocephalus and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Patients with persisting deficits may require specialist rehabilitation on a dedicated rehabilitation unit.

Diseases of the spinal cord

Spinal cord syndromes

Acute cord syndrome presenting as an emergency

Cauda equina syndrome

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disorder causing T- and B-cell dysfunction, is characterized by episodes of demyelination that are disseminated in time and space throughout the CNS. Patients usually present with discrete episodes (relapsing–remitting type) and after many years may develop gradually progressive disability without relapses (secondary progressive). Clinical features of a relapse depend on the site affected but often consist of a combination of positive and negative sensory symptoms, weakness, ataxia, myelitis or episodes of optic neuritis, usually evolving over days and resolving fully or partially over weeks. Optic neuritis is inflammation of the nerve with disc swelling and causes visual loss. Retrobulbar neuritis refers to inflammation behind the disc causing visual loss but with no ophthalmoscopic signs.

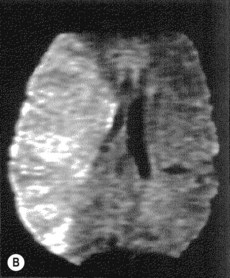

Investigations

Symptomatic treatment

Disease-modifying treatments

Disorders of the neuromuscular junction

Myasthenia gravis (MG)

Diagnostic investigations

Treatment

Dementia

Clinical assessment

Treatable causes for dementia are rare. Investigate all patients (see below). Additional tests may be required in younger patients and those with rapid progression. Depression can present as ‘pseudo-dementia’ and is treatable.

Investigations

• All patients

Motor neurone disease

Motor neurone disease (also called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/Lou Gehrig disease in the USA) is caused by relentless destruction of the upper motor neurones and anterior horn cells in the brain and spinal cord. There is no involvement of the sensory system or motor nerves to the eyes and sphincters. The three main disease patterns are progressive muscular atrophy (mainly anterior horn cell), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (mixed upper and lower motor neurone) and progressive bulbar/pseudobulbar palsy. There can be a mixture of upper and lower motor neurone signs. Needle EMG characteristically shows extensive muscle denervation (including bulbar muscles, and abdominal or paraspinal muscles) with preserved motor conduction velocity.

Peripheral nerve disease

This affects a single nerve (mononeuropathy) to several individual nerves (multiple mononeuropathy/mononeuritis multiplex), or causes a distal symmetrical polyneuropathy that may be due to either direct axonal damage or, less often, demyelinating disease (see Guillain–Barré, p. 659). Neuropathy usually involves both motor and sensory modalities, but occasionally only motor or only sensory nerves are affected. Since peripheral nerves have long axons, they are metabolically vulnerable and there are therefore many possible causes of neuropathy, especially axonal neuropathy. Many drugs cause a neuropathy (Table 17.4).

| Drug | Neuropathy | Mode/site of action |

|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | S, M | D, A |

| Anti-retroviral drugs | S > M | A |

| Chloramphenicol | S, M | A |

| Chloroquine | S, M | A, D |

| Cisplatin | S | A |

| Dapsone | M | A |

| Disulfiram | S, M | A |

| Isoniazid | S, S/M | A |

| Metronidazole | S, S/M | A |

| Nitrofurantoin | S/M | A |

| Paclitaxel | S > M | A |

| Phenytoin | M | A |

| Suramin | M > S | D, A |

| Vincristine | S > M | A |

A, axonal; D, demyelinating; M, motor; S, sensory.

Axonal distal polyneuropathy

This typically produces length-dependent nerve involvement, the longest nerves (to the toes) being affected first with gradual proximal progression. A sock distribution of sensory loss, followed by eventual glove and stocking sensory loss, results. Reflexes are usually absent and distal weakness and wasting may be seen. Proprioception, vibration sensation and cutaneous sensation (e.g. pinprick, light touch) are tested, starting distally in the limbs and moving proximally.

Investigations

• Initial investigations

Management

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS)

Adams HPJr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711.

Hughes T. Stroke on the acute medical take. Clin Med. 2010;10:68-72.