39 Neurologic Diseases

It truly takes a village to meet the complex needs faced by children with neurologic conditions and their families. Front and center to this village are the parents and day-to-day care providers of such children, the ones who see the nuances of how a specific disease or condition manifests in an individual child. Medical teams bring expertise in the spectrum of problems seen in many children with similar conditions; parents often bring expertise in how these problems look in their child. Along with the medical needs of such children, families face myriad challenges that exist in the context of their hopes, fears, beliefs, values, the uncertainty of a their child’s condition, and the community where they live. Table 39-1 is an introduction to the expertise available from palliative care and hospice teams to assist with the needs of such children and their families.

TABLE 39-1 Team Member Expertise

| These individual areas of expertise are critical to managing the multidimensional needs encountered. Though an individual of an interdisciplinary team will bring in expertise in one of these areas of need, each member will bring skills in assisting with all areas. |

| Social workers |

| Provide emotional support to family, psychosocial assessment and supportive counseling in collaboration with other providers for families adjusting to palliative care issues, link to psychosocial and mental health resources in the local community, anticipate legal and financial needs including guardianship, government programs that cover some medical expenses, and special needs trust, and direct to appropriate resources |

| Child life specialists |

| Assist siblings with the fears of having a sister or brother with complex healthcare needs, assist families with memory making and legacy of the child, provide bereavement support, provide education around appropriate grief responses of children |

| Chaplains |

| Support faith traditions and spiritual values that promote healing and hope, support families as they face loss and grief, identify religious and cultural factors that can shape how a family faces illness and suffering, provide a supportive presence for sick children and their families, provide support and advice in learning how to respond to the suffering witnessed by medical care teams |

| Nurses |

| Assist with bedside assessment of pain and other distressing symptoms, work with families and other care providers to determine what specific features in a nonverbal child with NI indicate specific distressing symptoms such as pain and dyspnea, translate this information into a care plan that is translatable to other care providers, listen in real time during times of emotional and spiritual distress for families |

| Physicians and advance practice nurses |

| Expertise in symptom management, serve as mediators between the medical teams and families, assist with advanced directives by working with medical teams and families, assist with translating goals of care to how medical interventions can or cannot meet those goals, review autopsy, tissue and organ donation, and Brain and Tissue Bank with families |

Pediatric Palliative Care and Neurologic Conditions

Pediatric palliative care teams are commonly consulted to see children who have diseases and impairments of the nervous system. Of children enrolled in a pediatric palliative care project, 44% were categorized with a primary neurologic condition (24% of those were deemed progressive neurologic, 20% were CNS damage) and 15% frequently have associated neurologic impairment (10% with congenital anomalies and 5% with metabolic).1 Recent data for the Pediatric Advanced Care Team (PACT) at Children’s Hospital Boston and Dana Farber Cancer Institute categorized 37% neurologic and 10% genetic or metabolic.2 Unfortunately, little has been written about palliative care as it pertains to children with neurologic impairment (NI) and their families.

The personal challenges experienced by children and their families exist within the larger context of societal debates regarding medical decision making for such children. These discussions are guided and influenced by ethics, morality, religion, personal values, justice, resource usage, and quality of life. Case reports in the literature highlight the variability of this debate with examples of doing everything, possibly so as to not create the impression of discrimination based on disability3 and not offering treatment out of an assumption of poor quality of life.4 As society wrestles with these challenges, we must avoid bringing this debate to the bedside and instead be guided by legal and ethical knowledge while providing compassion and support.

Patient Population

There are a broad range of conditions with NI that benefit from pediatric palliative care.5 The conditions may be:

Conditions and suggested timing of palliative care consultation are summarized in Table 39-2; assistance with symptom management can occur at any point in time.

TABLE 39-2 Neurologic Conditions and Timing of Palliative Care Consults

| Category | Conditions | Timing of consultation |

|---|---|---|

| Severe disability causing vulnerability to health complications and/or palliative after diagnosis |

Unique experiences and challenges

Loss is a recurrent theme, starting from the time of diagnosis. This theme is often repeated when what the child cannot do and the ongoing problems that cannot be fixed are reviewed at medical appointments. This journey often includes chronic sorrow, a phrase used to describe sorrow over time in response to ongoing loss.6 Examples may include loss of functional ability, loss of ability to meet nutritional and fluid needs through eating, and loss of health. Families are also simultaneously exploring meaning and hope in the context of their values, beliefs, relationships, and supportive networks. They may find joy in little victories, outcomes that were not expected, as they navigate hope, meaning, loss, and uncertainty.

What to Expect: Life Expectancy Literature

Information about life expectancy demonstrates a wide variation. The more severe the motor disability, such as the inability to lift the head up when prone, the more likely the child will not survive to adulthood.7–12 Survival for individuals with CP that includes severe impairment in cognitive function, motor ability, vision and hearing was 50% at 13 years and 25% at 30 years.9 It is beneficial to understand that CP is not a diagnosis but a developmental label indicating impairment of motor control as a result of non-progressive impairment of the central nervous system acquired at an early age. Information and experience from CP is relevant to any disease that results in severe motor impairment.

Framework for Approaching Prognosis, Uncertainty, and Decision Making

Literature and experience demonstrates a wide range in life expectancy, yet has provided limited information on how families approach this uncertainty. Studies13,14 of the experience of families with children dying from neurodegenerative conditions identify how they navigate uncharted territory and use strategies such as seeking and sharing information, focusing on the child, reframing the experience, and promoting the child’s health. Factors influencing parental decisions to limit or discontinue medical interventions include perception of their child’s suffering, likelihood of improvement, perception of their child’s will to survive, quality of life, previous experience with end-of-life decision making for others, and financial resources.15,16

Illness trajectory as a guide to decision making

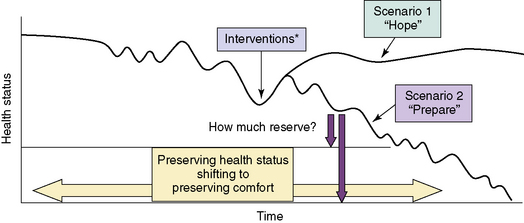

Adult literature describes illness trajectories for cancer, organ failure, and frailty.17,18 Using the latter two trajectories and experience, Fig. 39-1 provides a hypothetical framework for reflecting on and anticipating the trajectory of a child with NI. The figure is intended to guide families through decision making by using a reflection on the past benefit of interventions to anticipating the probable and possible future benefit by hoping for the best, preparing for the worst.19

The hypothetical disease trajectory highlights that many health issues in children with NI progress gradually with initial benefit and return to health and functional baseline with treatment available. Over time, less return to baseline will occur from the interventions available, reflecting the inability to fix the problems that are secondary to the permanent NI. Predicting outcome at the beginning of the trajectory before any decline in health status is seen can result in pressure of past success20 when the outcome is better than predicted. Asking a parent of a child with NI to make a decision to limit interventions before the child has had any significant decline in health may feel as if the emphasis is on limiting interventions because of the disability. By identifying associated health problems, monitoring for changes in health status, and noting any decreased benefit from treatments, we can identify individuals with NI who are at risk for life-threatening events.

Reflective questions with parents and care providers:

Advance care planning: how to hope and prepare

Areas of need as a result of slow decline include planning for future problems, avoiding interventions of limited benefit, and assistance for long-term caregivers.21 A goal is to facilitate planning by giving physicians permission to discuss what-if scenarios while giving parents permission to maintain hope. Palliative care can assist with this process by exploring psychosocial, spiritual, and physical needs that impact on decisions, such as the worry of giving up, a sense of needing to do something, and the fear that treating physical suffering will result in an early death. Given the inherent challenge of determining when goals shift from preserving health status to preserving comfort, medical, and palliative care are ideally integrated together for children with NI.22,23 Through this process of exploration with families and by integrating symptom-directed treatment into medical care plans, we can minimize the impression of choosing treatment that preserves life vs. comfort care that means giving up.

Several details about resuscitation are important for children with NI:

This is also a time to review that a decline in health is not a result of the care provided at home or a result of decisions made. Rather, it reflects the health problems that cannot be cured or fixed, while providing reassurance that interventions will be used for as long as the parents identify them as meeting goals. Several articles provide further beneficial communication strategies.24,25

Documenting, Communicating, and Coordinating Plans of Care

Symptom Management

Children with NI experience pain more frequently than the general pediatric population.26–29 Caregivers of children with severe cognitive impairment reported 44% experiencing pain each week over a 4-week interval. Pain frequency was higher in the most impaired group of children.27 In a study of nonverbal cognitively impaired children, caregivers reported that 62% experienced five or more separate days of pain and 24% experienced pain almost daily.29 In addition, children with severe-to-profound cognitive impairment were found to have elevated pain scores at baseline on two pain assessment scales.30

Other distressing symptoms commonly encountered in children with NI include: 31–33

In addition, depression and anxiety may be experienced at an increased rate by children with a muscular dystrophy (MD) such as Duchenne MD.34 Unfortunately, few studies have explored symptom management in children with NI both during life and at the end of life.

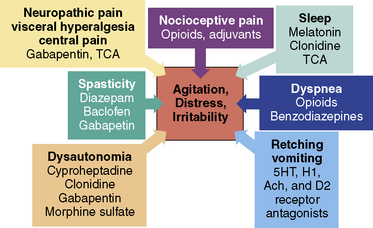

General approach

This section will outline management of distressing symptoms for children with NI (Fig. 39-2). This allows the healthcare provider to consider interventions that may benefit several problems. This can be helpful because it is not always possible to determine which symptoms or problems are the primary source of distress and which ones are the secondary manifestations in these children. Is the nonverbal neurologically impaired child irritable and in distress because of spasticity or is the spasticity secondary to underlying pain? Are the signs and symptoms of dysautonomia caused by pain, mimic the appearance of pain, or do the associated problems of dysautonomia contribute to pain? Given these challenges, it is helpful to focus on all potential sources of distressing symptoms, including neuropathy. The focus of this section will be on nonverbal children with NI given the inherent challenge with this group.

Assessment

The options for assessing presence and severity of pain include self-report, observational assessment of behaviors in nonverbal children, and assessment of physiological markers. Knowledge of the child’s cognitive level allows selection of a validated pain rating tool appropriate for the level of intellectual function such as The Poker Chip tool, the Oucher,35 and the Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale36 for children at a cognitive level of 5 to 6 years.

Assessment Tools

Observational pain assessment tools assist with identifying the presence of pain and monitoring improvement in pain when an intervention is introduced. (Box 39-1).37–49 In a comparison of the revised-Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (r-FLACC) tool, the Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Postoperative Version (NCCPC-PV), and the Nursing Assessment of Pain Intensity (NAPI), the r-FLACC and NAPI were identified as having a higher overall clinical utility based on complexity, compatibility, and relative advantage.37 The r-FLACC was the tool most preferred by clinicians in terms of pragmatic qualities.

BOX 39-1 Pain Assessment Tools for Non-Verbal Neurologically Impaired Children

The Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Revised (NCCPC-R)40,41

30-item standardized pain assessment tool for children with severe cognitive impairment.

Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP)42,43

Sensitivity (1.0) and specificity (0.91) optimized at a cut-off of 14/60

Available to download from the web following registration at www.ppprofile.org.uk.

Evaluation

This section discusses the sources of pain in neurologically impaired children.

Nocioceptive: Tissue Injury and Inflammation

Commonly recognized pain sources in children with NI include acute sources, such as fracture, urinary tract infection, or pancreatitis;51 and chronic sources, such as gastroesophageal reflex (GER), constipation, feeding difficulties from delayed gut motility, positioning, spasticity, hip pain, or dental pain. (Box 39-2).

BOX 39-2 Etiology of Pain/Irritability in Nonverbal Neurologically Impaired Children

Neuropathic: Peripheral Neuropathy and Central Pain

Neuropathic pain conditions are those associated with injury, dysfunction, or altered excitability of portions of the peripheral, central, or autonomic nervous system. It can be caused by compression, transection, infiltration, ischemia, or metabolic injury. Common features of neuropathic pain conditions include: descriptors such as burning, shooting, electric, or tingling; motor findings of spasms, dystonia, and tremor; and autonomic disturbances of erythema, mottling, and increased sweating.50

There are many reasons to consider neuropathic pain in children with NI. Experience shows that a nocioceptive pain source may not be identified or pain may continue despite treatment of an identified source. “Screaming of unknown origin” was used to describe children with neurologic disorders, severe developmental delay, neurodegeneration, or severe motor impairments with persistent agitation, distress, or screaming, acknowledging that evaluation often does not identify a specific nociceptive cause.52 Pain in children with NI is typically thought to be nociceptive in origin; however, after repeated injury or surgery, neuropathic pain may also occur.53 In one case series, 6 children with cerebral palsy developed neuropathic pain following multilevel orthopedic surgery.54 Onset of symptoms ranged from 5 to 9 days. Interventions included gabapentin in 4 children, amitriptyline in 2, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for 5, with improvement in symptoms over variable periods of time. Although not reported, experience in nonverbal children with NI identifies development of crying spells increasing in intensity weeks to months following major surgery, such as for neuromuscular scoliosis. Medications used for neuropathic pain include opioids, tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline and amitriptyline, and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, and lamotrigine.50

Visceral Hyperalgesia

The gastrointestinal tract is commonly identified by parents as a source of pain in neurologically impaired children. It has been identified as the most frequent source of all episodes of pain in children with severe cognitive impairment.27,55 Pain of unknown cause was the most intense, followed by pain attributed to the bowels, gastrointestinal tract, and digestive pain. In children with NI, significantly higher rates of pain were reported in those with a gastrostomy tube and those taking medications for feeding, gastroesophageal reflux, or gastrointestinal motility.28 This association between pain and gastrointestinal symptoms led to the hypothesis that some children with NI experience visceral hyperalgesia that benefits from gabapentin.56 This potential source of pain is reviewed in more detail in the section on retching and vomiting.

Central Pain

Central pain, also referred to as thalamic pain syndrome, is a recognized source of pain in adults with insults to the central nervous system such as from multiple sclerosis or following a cerebral vascular accident. Adults describe pain symptoms as burning, aching, throbbing, and the sensation of pins and needles. Associated symptoms include visceral pain, such as an exaggerated sensation of painful fullness from bladder and visceral distention. Symptoms are often poorly localized and constant as well as mixed with brief bursts of intense pain. The mechanisms that result in central pain appear similar but are not identical to peripheral neuropathic pain. Interventions with reported benefit include nortriptyline, gabapentin, lamotrigine, with lack of benefit from carbamazepine.57,58 Central pain as a source of pain has not been described in children, though is likely a source for consideration in children with NI.

Management

General Approach to Management of Distressing Symptoms in Nonverbal Children with NI

Good pain management starts with an assessment for treatable sources of pain, such as urinary tract infection, gastroesophageal reflux, and pancreatitis. For chronic sources of nociceptive pain, such as hip subluxation, pain management is guided by the principles of the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder.52,59–61

In addition to assessment for nociceptive sources of pain, neuropathy should be considered for the reasons previously discussed. For persistent distress that suggests pain, nonverbal children with NI often benefit from a medication trial that targets pain syndromes such as neuropathic pain, visceral hyperalgesia, or central pain. Medications best studied for these sources of nerve pain include gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (Table 39-3). There are reasons to start with gabapentin, including a good safety profile and no interactions with other drugs. Gabapentin has been found to be safe in children at doses up to 78 mg/kg/day.62 Pharmacokinetics indicate that children under 5 years of age require the highest doses.63 Gabapentin is readily available in an oral solution. Pregabalin is an alternative option known to have higher oral bioavailability compared to gabapentin (90% vs. 33% to 66 %) with a linear increase in plasma concentration with increasing doses compared with gabapentin’s decreasing bioavailability at higher doses. At this time there is no data to indicate that this results in a greater clinical benefit for children.

| Gabapentin |

Adapted from Hauer JM. Respiratory symptom management in a child with severe neurologic impairment. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10 (5): 1201-1207.

Spasticity

Treatment is intended to reduce the excessive muscle tone, with the goal of improving a patient’s functional capacity and comfort. Various therapeutic interventions are available, including physical therapy, medications, and surgery. There are few randomized controlled trials of oral drugs, especially in children. There is weak evidence demonstrating the efficacy of medications such as benzodiazepines, baclofen, dantrolene, and α2-adrenergic agonists of clonidine and tizanidine.64,65 There have been only two trials comparing drugs, tizanidine vs. diazepam and tizanidine vs. baclofen, with no significant differences noted between medications in either trial.66,67 Adverse drug reactions are common, and highest with dantrolene (64% to 91%).64 Side effects commonly seen with all medications include sedation, drowsiness, and muscle weakness. Side effects tend to be dose related and disappear when doses are reduced. In patients with multiple sclerosis, evidence identifies benefits of treating spasticity with gabapentin without experiencing sedation.68 This may indicate benefit to children with demyelinating or other neurodegenerative conditions but warrants further study.

Autonomic Dysfunction

As with other symptoms, evaluation should include a search for factors that may exacerbate the features of dysautonomia, including a review of potential sources of pain. Treatment for dysautonomia in neurologically impaired children has been poorly studied. Treatment options include benzodiazepines, bromocriptine, clonidine, oral and intrathecal baclofen, beta agonists such as metoprolol, and morphine sulfate. Literature is limited to case reports, predominantly in patients with traumatic brain injury. In a review of case reports of hypothalamic dysfunction, cyproheptadine was identified to benefit 4 individuals, including minimizing or eliminating symptoms of temperature instability, diaphoresis, vomiting, and abdominal pain.69 Other interventions used in patients in this review without benefit included antiepileptics, haloperidol, diazepam, and clonidine. A recent case series of 6 patients following traumatic brain injury identified improvement with gabapentin when symptoms of agitation, dysautonomia, and spasticity persisted despite treatment with bromocriptine, clonidine, ITB pump, metoprolol, morphine, and benzodiazepine.70 Finally, 13 out of 15 individuals with familial dysautonomia experienced a decrease in symptoms of nausea, retching, tachycardia, and flushing on pregabalin.71 Most patients were already using clonidine and a benzodiazepine. In children with NI, a therapeutic trial for pain should be considered because it is difficult to determine when features of dysautonomia are indicating underlying pain. In addition to scheduled medications, children with intermittent autonomic storms, often manifested by an acute onset of facial flushing, sweating, tachycardia, retching, agitation, and stiffening, may benefit from use of clonidine, diazepam, and morphine sulfate as needed during these episodes.

Medication Toxicities

Although uncommon, the features of serotonin syndrome and neuroleptic malignant syndrome include autonomic dysfunction and can be a result of medications used in this population. Awareness and monitoring for changes from a child’s baseline can alert us to these possible drug effects. Features of serotonin syndrome include tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, mydriasis, increased bowel sounds, hyperreflexia, clonus, agitation, and rigidity.72 Drugs commonly implicated include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Other drugs reported, often when used in combination, include: trazadone, fentanyl, tramadol, risperidone, ondansetron, metoclopramide, and valproate. Management includes removal of causative medications, use of cyproheptadine as a 5HT2 antagonist, and supportive care for other associated problems. Features of neuroleptic malignant syndrome are similar and include muscle rigidity, autonomic dysfunction, and altered mental status, most commonly caused by dopamine antagonists such as haloperidol. It has also been associated with tricyclic antidepressants and some anticonvulsants.73

Agitation and Delirium

Agitation is considered an unpleasant state of arousal. It may present as loud speech, crying, increased motor activity, increased autonomic arousal of diaphoresis or increased heart rate, inability to relax, or disturbed sleep-rest pattern. Symptoms in agitation overlap with anxiety though are noted to have more motor rather than psychological manifestations. In contrast, delirium is a disturbance of consciousness with an acute onset over hours to days. Associated features include fluctuating course, disordered thinking, a change in cognition, inattention, altered sleep-wake cycle, perceptual disturbances, and psychomotor disturbances.74,75 Causes include opioid or anticholinergic medications; metabolic disturbances of infection, dehydration, renal, liver, or electrolyte; pain; and impairment of vision or hearing.

Seizures

Seizures are frequently identified in children with NI. Such children are typically followed by a pediatric neurologist. Palliative care physicians can assist them through knowledge of side effects with medications and the ketogenic diet such as risk of renal stones. Other events may masquerade as a seizure such as myoclonus, which is a brief, involuntary twitching of a muscle or a group of muscles, and episodes of arching or posturing. We can also assist by working with the child’s neurologist to determine a plan for breakthrough seizures using rescue medications. This may include diazepam rectal gel, Diastat, or midazolam, which can be given sublingual and intranasal. There is increasing evidence that midazolam may be more effective than diazepam.76–78 Finally, we can assist parents if they are experiencing changes in their child’s health status occurring in conjunction with refractory epilepsy.

Sleep Disturbance

Treating sources of distress will often improve sleep in children with NI. Pharmacologic treatments to consider include melatonin,79,80 antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and trazodone,81–83 clonidine,84 and antipsychotics, especially for patients with delirium.85 When using melatonin for children with NI, some advocate that as the severity of disability increases, higher doses, occasionally even up to 15 mg, may be beneficial.80 Benzodiazepines tend to be overused, leading to dependency and tolerance, and should only be used in a time-limited manner and discontinued or weaned following short-term use.86 Nonpharmacologic interventions include a consistent bedtime and routine, quiet, a dark environment, and stimulus control.85 When sleep problems are linked to symptoms such as pain or dyspnea, or correlated with an underlying problem such as obstructive apnea, treatment of the underlying condition may improve sleep.

Methadone

Methadone is a beneficial option for symptom management in children with NI. Given some of the complexity, there may be benefit in initiating other medication trials first, such as gabapentin, given its safety and no interactions with other drugs, if suboptimal benefit initiate nortriptyline next, with methadone used as a third-line symptom management intervention. Another reason for this order is the greater benefit with the combination of gabapentin and nortriptyline for neuropathic pain over either one given solely.87

Respiratory Health in Children with NI

Children with severe neurologic impairment have a high incidence of respiratory problems.88 Recurrent respiratory illness leading to respiratory failure is the most common cause of mortality in children with severe cerebral palsy.10,11 Aspiration is a frequent factor, identified in 31% to 68% of children with cerebral palsy.89–91 Aspiration pneumonia in neurologically impaired children is best understood as an acute exacerbation resulting from chronic contributing factors. Those factors include:

Dyspnea

Measures of respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, blood gas levels, and family perception do not necessarily correlate with the patient’s perception of breathlessness. Instruments such as the Respiratory Distress Observational Scale (RDOS) are being evaluated for use in adults unable to report about dyspnea.106 When assisting parents in assessing for dyspnea in a nonverbal child, strategies are similar to those used in pain assessment of such children. Assessment can include asking a parent if he or she has observed the child to be in distress or appear anxious during a respiratory exacerbation. Behaviors indicating distress may include facial expression, appearing restlessness, or becoming withdrawn. It can also be helpful to instruct parents and care providers to breathe along with the child for 1 minute as an indirect indicator of the child’s effort of breathing.

Treating dyspnea is typically focused on identifying and aggressively treating the underlying cause. Evidence is established in adults for using interventions to alleviate dyspnea that persists despite maximum medical management of identified causes. These interventions include an oxygen trial, cool air from a fan or open window, repositioning, lorezepam for associated anxiety, and morphine sulfate. A recent review from the American College of Physicians identified strong evidence for treating adults with dyspnea from chronic lung disease with short-term opioids.107,108 Evidence includes demonstration of significant improvement in refractory dyspnea in participants completing a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with no significant episodes of sedation.109 Several studies have demonstrated the safety of using morphine sulfate for management of dyspnea that occurs despite maximum treatment of the underlying cause without development of respiratory depression.110–112 A suggested starting dose for an opioid naive patient is 25% to 30% of the dose used for pain with a maximum starting dose of 5 mg orally. If the patient is already on an opioid, increase the dose by 30%.

As a decline in respiratory status occurs despite management of these contributing factors, respiratory distress during exacerbations is likely an under-recognized symptom in children with NI. Using evidence for managing dyspnea in adults, children deserve symptom management of respiratory distress incorporated into medical care plans (Table 39-4). 113 For example, the table identifies antibiotics that provide coverage of anaerobic bacteria along with other oral bacteria when treating children who chronically aspirate oral secretions.114–118 Morphine sulfate is included in Table 39-4 to remind us to ask if there is distress during respiratory exacerbations and to include that information in care plans when distress is identified. This allows integration of symptom management into acute medical care plans in advance of seeing limited benefit from chronic and acute medical interventions. Overall, this will assist with future decisions by assuring that comfort is part of the care plan and avoid decisions to use interventions offered being made solely out of fear of suffering.

TABLE 39-4 Respiratory Home Management: Medical and Symptom Treatment Strategies

| Chronic interventions | |

|---|---|

| Suctioning | As needed for comfort |

| Oxygen | Assessed by appearance of patient or by oximeter |

| Albuterol nebulizer | Every 3-4 hrs for coughing, wheezing, congestion |

| Ipratropium (Atrovent) nebulizer | Every 3-4 hrs for coughing, wheezing, congestion |

| Saline or Mucomyst nebulizer | As needed for thick secretions |

| Chest physiotherapy or vest | 2 times/day, increase to 4 times/day with increased symptoms* |

| Nebulized budesonide (Pulmicort) | 2 times/day, increase to 4 times/day with increased symptoms* |

| Salmeterol (Serevent) | Family history of allergies or benefit from daily albuterol |

| Acute interventions | |

| For respiratory exacerbations from chronic aspiration | |

| Clindamycin, Augmentin or Levofloxacin/Moxifloxacin† | 10-14 days |

| Systemic steroids (prednisone)‡ | 5 days |

| Additional interventions | |

| For symptom management and end-of-life care | |

| Fan on face | Relieves sensation of breathlessness |

| Morphine sulfate | |

* Symptoms include increased coughing, secretions, congestion, respiratory rate and breathing effort.

† Use when respiratory symptoms persist or worsen despite an increase in chronic interventions.

‡ Include with third or fourth exacerbation, sooner if symptoms return within two months of antibiotic course.

§ Features suggesting respiratory distress include facial expression such as grimacing, appearing restlessness, having an anxious look, stiffening, tears, or becoming withdrawn.

Adapted from Hauer JM. Respiratory symptom management in a child with severe neurologic impairment. J Palliat Med 2007; 10(5):1201-1207. Table 39-1. Reprinted with permission from Journal of Palliative Medicine.

Nausea, Retching, Vomiting, and Feeding Intolerance

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in children with severe NI.27–29 This includes pain localized to the gut as noted in the pain section. Vomiting in these children is commonly attributed to GERD.119 Alternatively, stimulation of the emetic reflex is likely an under-reported source of symptoms in these patients.100,120 Experience and limited evidence suggests the benefit of considering sources beyond GERD. Considerations include visceral hyperalgesia, activation of the emetic reflex, and dysautonomia (Table 39-5).

TABLE 39-5 Medications for Retching, Vomiting, Feeding Intolerance in Children with NI

| Activation of the emetic reflex | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medication | Receptor antagonist | Dose |

| Ondansetron (Zofran) | 5HT3 | 0.15 mg/kg PO/IV q 8 hr prn (maximum 8 mg) |

| Metoclopramide (Reglan) | D2—GI tract | 0.1-0.2 mg/kg PO/IV q 6 hr (maximum 10 mg) |

| Haloperidol (Haldol) | D2—CTZ, H1 & Ach | 0.01-0.02 mg/kg PO q 8 hr prn (maximum 1 mg) |

| Promethazine (Phenergan) | H1 & Ach (weak D2) | 0.25-0.5 mg/kg PO/IV q 4 hr prn (maximum 25 mg) |

| Diphenhydramine (Benedryl) | H1 | 0.5-1 mg/kg PO/IV q 6 hr prn (maximum 50 mg) |

| Cyproheptadine (Periactin) | 5HT2, H1 & Ach | |

| Visceral hyeralgesia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medication | Mechanism of action | Dose |

| Gabapentin | Thought to inhibit excitation by binding to the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage dependent Ca ion channels in the central nervous system | See Table 39-3 |

| Nortriptyline | Presynaptic reuptake inhibition in the CNS of norepinephrine and serotonin, both inhibitors of pain transmission | See Table 39-3 |

| Dysautonomia | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medication | Mechanism of action | Dose |

| Clonidine | Centrally acting α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, reducing sympathetic outflow | |

| Cyproheptadine | See above | See above |

| Gabapentin | See above | See above |

| Morphine sulfate | Binds CNS opioid receptors | 0.3 mg/kg PO/SL q 3-4 hr prn “autonomic storm” |

Pathways that result in nausea and vomiting

An understanding of the pathways, receptors, and neurotransmitters involved in generating nausea, vomiting, and retching is critical to identifying treatment that can alleviate these symptoms.121–123 The final common pathway resulting in nausea and vomiting is the vomiting center (VC) located in the medulla. The VC is triggered by numerous inputs, including the chemoreceptor trigger zone, cortical inputs, meningeal and ventricular mechanoreceptors, vestibular input, and vagal and glossopharyngeal input.

Visceral Hyperalgesia as a Source of Vomiting, Retching, and Feeding Intolerance

Visceral hyperalgesia is an altered response to visceral stimulation, resulting in a decreased activation threshold for pain in response to a stimulus, such as intraluminal pressure.124 In a case series of 14 medically fragile children with continued retching and vomiting despite maximal medical treatment and Nissen fundoplication, visceral hyperalgesia was identified in 12 children as a source of symptoms.125 Tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, cyproheptadine, and dicyclomine were used in various combinations depending on evaluation results, with 11 children reported as “better” or “much better” and a decrease in the mean number of retching episodes per day from 14 to 1.5. A case series of nine neurologically impaired children with symptoms indicating pain, feeding intolerance, and disrupted sleep, identified significant improvement following use of gabapentin titrated to standard doses.56 This suggests that gastrointestinal and pain symptoms may improve with medical management directed toward visceral hyperalgesia when symptoms persist despite management of the more commonly recognized gastrointestinal problems. One report speculates that repeated painful gastrointestinal experiences during infancy contributes to sensitization of visceral afferent pathways.125 It is interesting to note the higher incidence of pain in children with a gastrostomy feeding tube and taking medications for GERD.28 Children with NI have an increased frequency of such sensitizing experiences, including GERD, constipation, gastrostomy tube placement, and fundoplication.119,126

Information that suggests visceral hyperalgesia in nonverbal children with NI includes:

Retching was identified to benefit from alimemazine, a phenothiazine derivative structurally related to such medication as chlorpromazine.127 As with other phenothiazine derivatives, various properties may account for this noted benefit with retching, including antihistamine, anticholinergic, antidopinergic, and antiserotonergic. Though alimemazine is not available in the United States, cyproheptadine and other medications that block the receptors that trigger nausea and vomiting may benefit children with NI and retching.

As identified earlier, children with vomiting and symptoms of retching, tachycardia, sweating, or flushing indicating dysautonomia, retching, forceful vomiting, pallor, or sweating indicating activation of the emetic reflex, or pain indicating visceral hyperalgesia likely do not benefit from anti-reflux surgery.100,120 Esophagogastric disconnection is another surgical intervention that has been proposed for persistent GERD. In two case series reviewing the use of esophagogastric disconnection, morbidity (30% to 43% early complications, 41% to 43% late complications) and mortality (22% to 29%) were high.128,129 Though used for GERD, patients were also noted to have symptoms of retching, likely indicating a process distinct from GERD. It is essential that medical and symptom management be maximized before considering this surgical intervention and that any surgical intervention for GERD be considered cautiously in neurologically impaired children with retching (see Table 39-5).

Intestinal pseudo-obstruction

Intestinal pseudo-obstruction, also referred to as Ogilvie syndrome, is a clinical picture that suggests mechanical obstruction, but in the absence of any evidence of any obstruction in the intestine. Patients at risk include children with mitochondrial disorders and conditions with significant autonomic dysfunction, such as autonomic dyreflexia following spinal cord injury. Children with severe NI may be at risk for this clinical picture in the post-operative period with a clinical picture of prolonged ileus.130 Neostigmine has been reported to benefit some patients with acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction, when it fails to resolve with supportive therapy and management of contributing factors.131 It must be used with caution, given the potential side effects, including bradycardia, hypotension, increased pain, increased airway secretions and bronchial reactivity. A test dose of 0.01–0.02 mg/kg/dose intravenously can be given in the hospital to allow monitoring, titrated up to 0.08 mg/kg/dose if needed. The oral equivalent is approximately 15 mg oral to 0.5 mg intravenous. Glycopyrrolate has been suggested in conjunction with neostigmine to minimize effects of bradycardia. Children with significant recurrent episodes, as seen with mitochondrial myopathies, may benefit from as needed neostigmine once a dose has been established, though this warrants further study. Other medications that have been considered include 5-HT4 receptor agonists such as tegaserod and somatostatin analogues such as octreotide.

Medical Nutrition and Hydration

Forgoing medical nutrition and hydration remains one of the more difficult areas given the symbolic significance of nutrition, the myths about dehydration and starvation, and under-recognition of the complications of artificial hydration and nutrition.132 The American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement recognizes that “Life-sustaining medical treatment encompasses all interventions that may prolong the life of patients. …includes less technically demanding measures such as antibiotics, insulin, chemotherapy, and nutrition and hydration provided intravenously or by tube.”133 It is permissible to discontinue medical nutrition and hydration when it is prolonging or contributing to suffering.134–137

End-of-Life Care

What is life limiting in severe disability?

Several categories can be identified that account for shortened life spans in children with NI.

Autopsy, Brain and Tissue Bank, and Organ Donation

The goal of the Brain and Tissue Bank is to advance research on developmental disorders. It serves the critical purpose of collecting, preserving, and distributing human tissues to scientific investigators who are dedicated to the improved understanding, care and treatment of developmental disorders, offering hope to others. The procedure to recover tissue at time of death will not interfere with open casket viewing. The Brain and Tissue Bank covers all expenses related to the recovery of tissue. All donor information remains anonymous and anyone who registers holds the right to withdraw at any time. Further information for families can be found at www.btbankfamily.org.

Increasingly, pediatric hospitals are developing policies that support donation after cardiac death programs. There is increasing awareness of this approach as noted by the number of cases that were initiated by the family.138,139 Organ donor programs that include donation after cardiac death may have benefit by providing an opportunity for legacy building. Further review is needed on how this impacts end-of-life care and bereavement.

Bereavement

Unique areas of bereavement are seen in parents of children with NI. The limited research has not found differences on measures of grief between parents of children with developmental impairment and other parents.140 Themes identified that are unique to parents of children with NI include: working through two difficult transitions, first when the child was diagnosed with NI and second when the child died; a need to justify their love of their child to others; parents’ lack of opportunity to share their grief, resulting in a socially imposed silent grief; loss of an intensive caregiver role and support group membership; conflicting feelings of sadness; and relief over prior fears about the child’s future. Bereavement is an essential part of supportive care with importance in attending to the experiences unique to families of children with NI.

1 Hays R.M., Valentine J., Geyer J.R. The Seattle Palliative Care Project: Effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):716-728.

2 Duncan J., Spengler E., Wolfe J. Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):279-287.

3 Lohiya G.S., Tan-Figueroa L., Crinella F.M. End-of-life care for a man with developmental disabilities. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(1):58-62.

4 Tuffrey-Wijne I. The palliative care needs of people with intellectual disabilities: a literature review. Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):55-62.

5 Himelstein B.P., Hilden J.M., Boldt A.M., Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1752-1762.

6 Scornaienchi J.M. Chronic sorrow: one mother’s experience with two children with lissencephaly. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17(6):290-294.

7 Patja K., Iivanainen M., Vesala H., et al. Life expectancy of people with intellectual disability: a 35-year follow-up study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2000;44(Pt 5):591-599.

8 Patja K., Mölsä P., Iivanainen M. Cause-specific mortality of people with intellectual disability in a population-based, 35-year follow-up study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2001;45(Pt 1):30-40.

9 Hutton J.L., Pharoah P.O. Life expectancy in severe cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(3):254-258.

10 Hemming K., Hutton J.L., Pharoah P.O. Long-term survival for a cohort of adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(2):90-95.

11 Strauss D., Cable W., Shavelle R. Causes of excess mortality in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(9):580-585.

12 Katz R.T. Life expectancy for children with cerebral palsy and mental retardation: implications for life care planning. Neuro Rehabil. 2003;18(3):261-270.

13 Steele R. Navigating uncharted territory: experiences of families when a child is dying. J Palliat Care. 2005;21(1):35-43.

14 Steele R. Strategies used by families to navigate uncharted territory when a child is dying. J Palliat Care. 2005;21(2):103-110.

15 Meyer E.C., Burns J.P., Griffith J.L., et al. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):226-231.

16 Sharman M., Meert K.L., Sarnaik A.P. What influences parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life support? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(5):513-518.

17 Murray S.A., Kendall M., Boyd K., et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1007-1011.

18 Lunney J.R., Lynn J., Foley D.J., et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387-2392.

19 Back A.L., Arnold R.M., Quill T.E. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):439-443.

20 Graham R.J., Robinson W.M. Integrating palliative care into chronic care for children with severe neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(5):361-365.

21 Dy S., Lynn J. Getting services right for those sick enough to die. BMJ. 2007;334(7592):511-513.

22 American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351-357.

23 Klick J.C., Ballantine A. Providing care in chronic disease: the ever-changing balance of integrating palliative and restorative medicine. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):799-812.

24 Levetown M., American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1441-e1460.

25 Mack J.W., Wolfe J. Early integration of pediatric palliative care: for some children, palliative care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):10-14.

26 Perquin C.W., Hazebroek-Kampschreur A.A., Hunfeld J.A., et al. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000;87(1):51-58.

27 Breau L.M., Camfield C.S., McGrath P.J., et al. The incidence of pain in children with severe cognitive impairments. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(12):1219-1226.

28 Houlihan C.M., O’Donnell M., Conaway M., et al. Bodily pain and health-related quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:305-310.

29 Stallard P., Williams L., Lenton S., et al. Pain in cognitively impaired, non-communicating children. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(6):460-462.

30 Defrin R., Lotan M., Pick C.G. The evaluation of acute pain in individuals with cognitive impairment: a differential effect of the level of impairment. Pain. 2006;124(3):312-320. Epub 2006 Jun 14

31 Drake R., Frost J., Collins J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(1):594-603.

32 Hunt A.M. A survey of signs, symptoms and symptom control in 30 terminally ill children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990;32(4):341-346.

33 Hunt A., Burne R. Medical and nursing problems of children with neurodegenerative disease. Palliat Med. 1995;9(1):19-26.

34 Roccella M., Pace R., De Gregorio M.T. Psychopathological assessment in children affected by Duchenne de Boulogne muscular dystrophy. Minerva Pediatr. 2003;55(3):267-276.

35 Beyer J.E., Aradine C.R. Content validity of an instrument to measure young children’s perceptions of the intensity of their pain. J Pediatr Nurs. 1986;1(6):386-395.

36 Wong D.L., Hockenberry-Eaton M., Wilson D., Winkelstein M.L., Schwartz P., editors. Wong’s essentials of pediatric nursing, ed 6, St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

37 Voepel-Lewis T., Malviya S., Tait A.R., et al. A comparison of the clinical utility of pain assessment tools for children with cognitive impairment. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(1):72-78.

38 Voepel-Lewis T., Merkel S., Tait A.R., et al. The reliability and validity of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability observational tool as a measure of pain in children with cognitive impairment. Anesth Analg. 2002;95(5):1224-1229.

39 Malviya S., Voepel-Lewis T., Burke C., et al. The revised FLACC observational pain tool: improved reliability and validity for pain assessment in children with cognitive impairment. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(3):258-265.

40 Breau L.M., Camfield C., McGrath P.J., et al. Measuring pain accurately in children with cognitive impairments: refinement of a caregiver scale. J Pediatr. 2001;138(5):721-727.

41 Breau L.M., McGrath P.J., Camfield C.S., et al. Psychometric properties of the non-communicating children’s pain checklist-revised. Pain. 2002;99(1–2):349-357.

42 Hunt A., Wisbeach A., Seers K., et al. Development of the paediatric pain profile: role of video analysis and saliva cortisol in validating a tool to assess pain in children with severe neurological disability. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(3):276-289.

43 Hunt A., Goldman A., Seers K., et al. Clinical validation of the paediatric pain profile. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(1):9-18.

44 Solodiuk J., Curley M.A. Pain assessment in nonverbal children with severe cognitive impairments: the Individualized Numeric Rating Scale (INRS). J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(4):295-299.

45 Closs S.J., Barr B., Briggs M., et al. A comparison of five pain assessment scales for nursing home residents with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. J Pain and Symptom Manage. 2004;27(3):196-205.

46 Chibnall J.T., Tait R.C. Pain assessment in cognitively impaired and unimpaired older adults: a comparison of four scales. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):173-186.

47 Feldt K.S. The checklist of nonverbal pain indicators (CNPI). Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1(1):13-21.

48 Regnard C., Reynolds J., Watson B., et al. Understanding distress in people with severe communication difficulties: developing and assessing the Disability Distress Assessment Tool (DisDAT). J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007;51(Pt 4):277-292.

49 Hølen J.C., Saltvedt I., Fayers P.M. The Norwegian Doloplus-2, a tool for behavioural pain assessment: translation and pilot-validation in nursing home patients with cognitive impairment. Palliat Med. 2005;19(5):411-417.

50 Berde C.B., Lebel A.A., Olsson G. Neuropathic pain in children. In: Schechter N.L., Berde C.B., Yaster M., editors. Pain in infants, children, and adolescents. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003:620-641.

51 Hauer J.M. Central hypothermia as a cause of acute pancreatitis in children with neurodevelopmental impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(1):68-70.

52 Greco C., Berde C.B. Pain management for the hospitalized pediatric patient. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2005;52:995-1027.

53 Oberlander T.R., Craig K.D. Pain and children with developmental disabilities. In: Schechter N.L., Berde C.B., Yaster M., editors. Pain in infants, children, and adolescents. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003:599-619.

54 Lauder G.R., White M.C. Neuropathic pain following multilevel surgery in children with cerebral palsy: a case series and review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15(5):412-420.

55 Breau L.M., Camfield C.S., McGrath P.J., et al. Risk factors for pain in children with severe cognitive impairments. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(6):364-371.

56 Hauer J., Wical B., Charnas L. Gabapentin successfully manages chronic unexplained irritability in children with severe neurologic impairment. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e519-e522.

57 Nicholson B.D. Evaluation and treatment of central pain syndromes. Neurology. 2004;62(5 Suppl 2):S30-S36.

58 Frese A., Husstedt I.W., Ringelstein E.B., et al. Pharmacologic treatment of central post-stroke pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(3):252-260.

59 Berde C.B., Sethna N.F. Analgesics for the treatment of pain in children. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(14):1094-1103.

60 Friedrichsdorf S.J., Kang T.I. The management of pain in children with life-limiting illnesses. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):645-672.

61 Goldman A., Hain R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook of palliative care for children. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

62 Korn-Merker E., Borusiak P., Boenigk H.E. Gabapentin in childhood epilepsy: a prospective evaluation of efficacy and safety. Epilepsy Res. 2000;38(1):27-32.

63 Haig G.M., Bockbrader H.N., Wesche D.L., et al. Single-dose gabapentin pharmacokinetics and safety in healthy infants and children. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41(5):507-514.

64 Krach L.E. Pharmacotherapy of spasticity: oral medications and intrathecal baclofen. J Child Neurol. 2001;16(1):31-36.

65 Montané E., Vallano A., Laporte J.R. Oral antispastic drugs in nonprogressive neurologic diseases: a systematic review. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1357-1363.

66 Bes A., Eyssette M., Pierrot-Deseilligny E., et al. A multi-centre, double-blind trial of tizanidine, a new antispastic agent, in spasticity associated with hemiplegia. Curr Med Res Opin. 1988;10:709-718.

67 Medici M., Pebet M., Ciblis D. A double-blind, long-term study of tizanidine (”Sirdalud“) in spasticity due to cerebrovascular lesions. Curr Med Res Opin. 1989;11:398-407.

68 Cutter N., Scott D.D., Johnson J.C., et al. Gabapentin effect on spasticity in multiple sclerosis: a placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(2):164-169.

69 Baguley I.J., Heriseanu R.E., Gurka J.A., et al. Gabapentin in the management of dysautonomia following severe traumatic brain injury: a case series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(5):539-541.

70 Kloos R.T. Spontaneous periodic hypothermia. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74(5):268-280.

71 Axelrod F.B., Berlin D. Pregabalin: A new approach to treatment of the dysautonomic crisis. Pediatrics. 2009. Jul 20. [Epub ahead of print]

72 Boyer E.W., Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-1120.

73 Halloran L.L., Bernard D.W. Management of drug-induced hyperthermia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16(2):211-215.

74 Del Fabbro E., Dalal S., Bruera E. Symptom control in palliative care—Part III: dyspnea and delirium. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):422-436.

75 Wusthoff C.J., Shellhaas R.A., Licht D.J. Management of common neurologic symptoms in pediatric palliative care: seizures, agitation, and spasticity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):709-733. xi

76 McIntyre J., Robertson S., Norris E., et al. Safety and efficacy of buccal midazolam versus rectal diazepam for emergency treatment of seizures in children: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):205-210.

77 Appleton R., Macleod S., Martland T. Drug management for acute tonic-clonic convulsions including convulsive status epilepticus in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2008. CD001905,

78 Mpimbaza A., Ndeezi G., Staedke S., et al. Comparison of buccal midazolam with rectal diazepam in the treatment of prolonged seizures in Ugandan children: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e58-e64.

79 Dodge N.N., Wilson G.A. Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders in children with developmental disabilities. J Child Neurol. 2001;16(8):581-584.

80 Jan J.E., Freeman R.D. Melatonin therapy for circadian rhythm sleep disorders in children with multiple disabilities: what have we learned in the last decade? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(11):776-782.

81 Collins J.J., Kerner J., Sentivany S., Berde C.B. Intravenous amitriptyline in pediatrics. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(6):471-475.

82 Davis M.P. Does trazodone have a role in palliating symptoms? Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(2):221-224.

83 Pranzatelli M.R., Tate E.D., Dukart W.S., et al. Sleep disturbance and rage attacks in opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome: response to trazodone. J Pediatr. 2005;147(3):372-378.

84 Schnoes C.J., Kuhn B.R., Workman E.F., et al. Pediatric prescribing practices for clonidine and other pharmacologic agents for children with sleep disturbance. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(3):229-238.

85 Sela R.A., Watanabe S., Nekolaichuk C.L. Sleep disturbances in palliative cancer patients attending a pain and symptom control clinic. Palliat Support Care. 2005;3(1):23-31.

86 Rosenberg R.P. Sleep maintenance insomnia: strengths and weaknesses of current pharmacologic therapies. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18(1):49-56.

87 Gilron I., Bailey J.M., Tu D., Holden R.R., Jackson A.C., Houlden R.L. Nortriptyline and gabapentin, alone and in combination for neuropathic pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9697):1252-1261. Epub 2009 Sep 30

88 Seddon P.C., Khan Y. Respiratory problems in children with neurological impairment. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:75-78.

89 Wright R.E., Wright F.R., Carson C.A. Videofluoroscopic assessment in children with severe cerebral palsy presenting with dysphagia. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:720-722.

90 Mirrett P.L., Riski J.E., Glascott J., et al. Videofluoroscopic assessment of dysphagia in children with severe cerebral palsy. Dysphagia. 1994;9:174-179.

91 Taniguchi M.H., Moyer R.S. Assessment of risk factors for pneumonia in dysphagic children: significance of videofluoroscopic swallowing evaluation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36:495-502.

92 Strauss D., Shavelle R., Reynolds R., et al. Survival in cerebral palsy in the last 20 years: signs of improvement? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(2):86-92.

93 Sleigh G., Brocklehurst P. Gastrostomy feeding in cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(6):534-539.

94 Finucane T.E., Christmas C., Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1365-1370.

95 Morton R.E., Wheatley R., Minford J. Respiratory tract infections due to direct and reflux aspiration in children with severe neurodisability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(5):329-334.

96 Jolley S.G., Herbst J.J., Johnson D.G., et al. Surgery in children with gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory symptoms. J Pediatr. 1980;96(2):194-198.

97 Kawahara H., Okuyama H., Kubota A., et al. Can laparoscopic antireflux surgery improve the quality of life in children with neurologic and neuromuscular handicaps? J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(12):1761-1764.

98 Cheung K.M., Tse H.W., Tse P.W., et al. Nissen fundoplication and gastrostomy in severely neurologically impaired children with gastroesophageal reflux. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12(4):282-288.

99 Bui H.D., Dang C.V., Chaney R.H., et al. Does gastrostomy and fundoplication prevent aspiration pneumonia in mentally retarded persons? Am J Ment Retard. 1989;94(1):16-19.

100 Richards C.A., Milla P.J., Andrews P.L., et al. Retching and vomiting in neurologically impaired children after fundoplication: predictive preoperative factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(9):1401-1404.

101 Carron J.D., Derkay C.S., Strope G.L., et al. Pediatric tracheotomies: changing indications and outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(7):1099-1104.

102 Berry J.G., Graham D.A., Graham R.J., et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes and hospital resource use of children after tracheotomy. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):563-572.

103 Vijayasekaran S., Unal R., Schraff S.A., et al. Salivary gland surgery for chronic pulmonary aspiration in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(1):119-123.

104 Raval T.H., Elliott C.A. Botulinum toxin injection to the salivary glands for the treatment of sialorrhea with chronic aspiration. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(2):118-122.

105 Tsirikos A.I., Chang W.N., Dabney K.W., et al. Life expectancy in pediatric patients with cerebral palsy and neuromuscular scoliosis who underwent spinal fusion. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45(10):677-682.

106 Campbell M.L. Psychometric testing of a respiratory distress observation scale. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):44-50.

107 Lorenz K.A., Lynn J., Dy S.M., et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):147-159.

108 Qaseem A., Snow V., Shekelle P., et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):141-146.

109 Abernethy A.P., Currow D.C., Frith P., et al. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial of sustained release morphine for the management of refractory dyspnoea. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):523-528.

110 Clemens K.E., Klaschik E. Symptomatic therapy of dyspnea with strong opioids and its effect on ventilation in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):473-481.

111 Allen S., Raut S., Woollard J., et al. Low dose diamorphine reduces breathlessness without causing a fall in oxygen saturation in elderly patients with end-stage idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Palliat Med. 2005;19(2):128-130.

112 Mazzocato C., Buclin T., Rapin C.H. The effects of morphine on dyspnea and ventilatory function in elderly patients with advanced cancer: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(12):1511-1514.

113 Hauer J.M. Respiratory symptom management in a child with severe neurologic impairment. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1201-1207.

114 Brook I., Finegold S.M. Bacteriology of aspiration pneumonia in children. Pediatrics. 1980;65(6):1115-1120.

115 Dreyfuss D. Aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(24):1868. letter

116 Brook I. Treatment of aspiration or tracheostomy-associated pneumonia in neurologically impaired children: effect of antimicrobials effective against anaerobic bacteria. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;35(2):171-177.

117 Allewelt M., Schuler P., Bolcskei P.L., et al. Ampicillin + sulbactam vs clindamycin +/- cephalosporin for the treatment of aspiration pneumonia and primary lung abscess. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(2):163-170.

118 Kadowaki M., Demura Y., Mizuno S., et al. Reappraisal of clindamycin IV monotherapy for treatment of mild-to-moderate aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients. Chest. 2005;127(4):1276-1282.

119 Del Giudice E., Staiano A., Capano G., et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations in children with cerebral palsy. Brain Dev. 1999;21(5):307-311.

120 Richards C.A., Andrews P.L., Spitz L., et al. Nissen fundoplication may induce gastric myoelectrical disturbance in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(12):1801-1805.

121 Santucci G., Mack J.W. Common gastrointestinal symptoms in pediatric palliative care: nausea, vomiting, constipation, anorexia, cachexia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):673-689.

122 Baines M.J. ABC of palliative care. Nausea, vomiting, and intestinal obstruction. BMJ. 1997;315(7116):1148-1150.

123 Wood G.J., Shega J.W., Lynch B., et al. Management of intractable nausea and vomiting in patients at the end of life: “I was feeling nauseous all of the time … nothing was working,”. JAMA. 2007;298(10):1196-1207.

124 Delgado-Aros S., Camilleri M. Visceral hypersensitivity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(Suppl 3):S194-S203.

125 Zangen T., Ciarla C., Zangen S., et al. Gastrointestinal motility and sensory abnormalities may contribute to food refusal in medically fragile toddlers. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(3):287-293.

126 Schwarz S.M., Corredor J., Fisher-Medina J., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of feeding disorders in children with developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):671-676.

127 Antao B., Ooi K., Ade-Ajayi N., et al. Effectiveness of alimemazine in controlling retching after Nissen fundoplication. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(11):1737-1740.

128 Burrati S., Kamenwa R., Dohil R., et al. Esophagogastric disconnection following failed fundoplication for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in children with severe neurological impairment. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:786-790.

129 Danielson P.D., Emmens R.W. Esophagogastric disconnection for gastroesophageal reflux in children with severe neurological impairment. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(1):84-87.

130 Gmora S., Poenaru D., Tsai E. Neostigmine for the treatment of pediatric acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(10):E28.

131 Ponec R.J., Saunders M.D., Kimmey M.B. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):137-141.

132 Casarett D., Kapo J., Caplan A. Appropriate use of artificial nutrition and hydration: fundamental principles and recommendations. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(24):2607-2612.

133 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Guidelines on foregoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):532-536.

134 American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Statement on artificial nutrition and hydration. www.aahpm.org/positions/nutrition.html., April 2, 2009. Accessed

135 Nelson L.J., Rushton C.H., Cranford R.E., et al. Forgoing medically provided nutrition and hydration in pediatric patients. J Law Med Ethics. 1995;23(1):33-46.

136 Stanley A.L. Withholding artificially provided nutrition and hydration from disabled children: assessing their quality of life. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(10):575-579.

137 Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Withholding or withdrawing life sustaining treatment for children: a framework for practice. www.rcpch.ac.uk/Publications/Publications-list-by-title#W., December 4, 2008. Accessed

138 Pleacher K.M., Roach E.S., Van der Werf W., et al. Impact of a pediatric donation after cardiac death program. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(2):166-170.

139 Naim M.Y., Hoehn K.S., Hasz R.D., et al. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s experience with donation after cardiac death. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1729-1733.

140 Reilly D.E., Hastings R.P., Vaughan F.L., et al. Parental bereavement and the loss of a child with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2008;46(1):27-43.