Chapter 16 Neurologic Aspects of Sexual Function

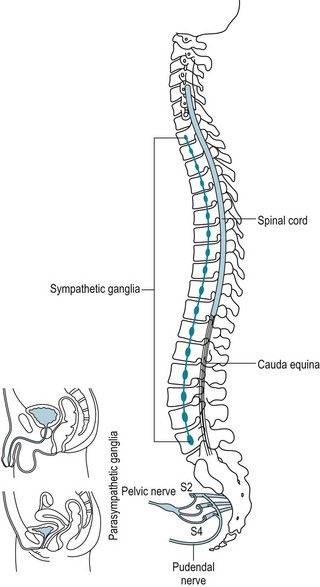

In the first pathway, the brain converts various stimuli, including sleep-related events, into neurologic impulses that are usually excitatory, although occasionally inhibitory. These impulses travel down the spinal cord. Some impulses descend all the way down to the cord’s sacral region where they exit to travel through the pudendal nerve. At this juncture, they leave the CNS to join the PNS (Fig. 16-1). Meanwhile, as if diverted to a parallel route, some impulses leave the spinal cord at its low thoracic and upper lumbar regions (T11–L2) to travel through the sympathetic division of the ANS. Still others leave the spinal cord’s lower sacral segments (S2–4) to travel through the parasympathetic division of the ANS.

FIGURE 16-1 The sacral spinal cord segments (S2–4) give rise to the pudendal nerves, which supply the genital muscles and skin. Those segments also supply the vaginal canal. They convey sensations for pleasure during sex and pain during vaginal delivery. The sympathetic and parasympathetic components of the autonomic nervous system also innervate the genitals, and the reproductive organs, bladder, sweat glands, and arterial wall muscles.

Neurologic Impairment

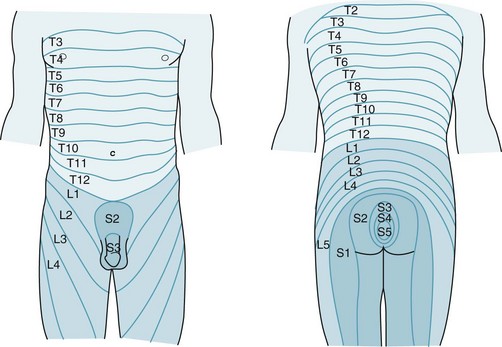

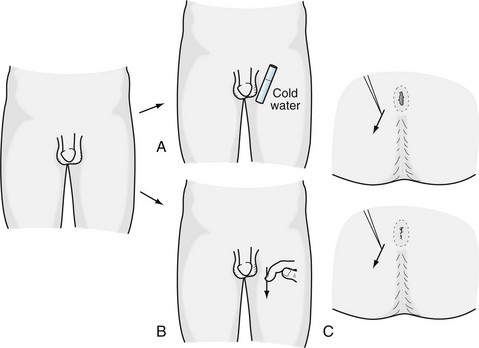

Without accepting a complete distinction between neurologic and psychologic sexual impairment, certain elements of the patient’s history (Box 16-1) and neurologic examination (Box 16-2) reliably indicate a neurologic origin. For example, either spinal cord or peripheral nerve injury might lead to a pattern of weakness and sensory loss below the waist or only around the genitals, anus, and buttocks – the “saddle area” (Fig. 16-2). Plantar and deep tendon reflex (DTR) testing will indicate which system is responsible: spinal cord injury causes hyperactive DTRs and Babinski signs, whereas peripheral nerve injury causes hypoactive DTRs and no Babinski signs. Both CNS and PNS impairment lead to loss of the relevant “superficial reflexes”: scrotal, cremasteric, and anal (Fig. 16-3).

Box 16-1

Symptoms Suggesting Neurologic Sexual Impairment

FIGURE 16-2 The sacral dermatomes (S2–5) innervate the skin overlying the genitals and anus, but the lumbar dermatomes innervate the legs.

FIGURE 16-3 A, The scrotal reflex: When the examiner applies a cold surface to the scrotum, the ipsilateral skin contracts and testicle retracts. B, The cremasteric reflex: Stroking the inner thigh elicits the same response. C, The anal reflex: When the examiner scratches the skin surrounding the anus, it tightens.

In many conditions, such as spinal cord injury or severe ANS damage, urinary and fecal incontinence accompany neurologic-induced sexual impairment because the bladder, bowel, and genitals share many elements of innervation. The anus, like the bladder, has two sphincters (see Fig. 15-5). Its internal sphincter, more powerful than the external one, constricts in response to increased sympathetic activity and relaxes to parasympathetic activity. The external sphincter of the anus is under voluntary control through the pudendal nerves and other branches of the S3 and S4 peripheral nerve roots. Thus, to produce a bowel movement, individuals must deliberately relax their external sphincter while the internal sphincter, under involuntary parasympathetic control, simultaneously relaxes.

Medical Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction

Many physicians prescribe yohimbine, a centrally acting α2-adrenergic antagonist (see Chapter 21). This medicine may slightly increase sympathetic vasomotor activity, provide mild psychologic stimulation, and create an aphrodisiac sensation. Although yohimbine may alleviate psychogenic erectile dysfunction, it does not help in cases of sexual function due to medical or neurologic illness. Moreover, it often causes anxiety.

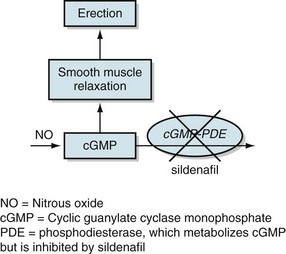

As their primary mechanism of action, these medicines – phosphodiesterase inhibitors – inhibit cGMP-phosphodiesterase. The resulting increased cGMP concentration promotes blood flow in the penis (Fig. 16-4).

FIGURE 16-4 As its mechanism of action, sildenafil inhibits cyclic guanylate cyclase monophosphate-phosphodiesterase (cGMP-PDE). The resulting increase in cGMP leads to smooth-muscle relaxation, which promotes vascular congestion in the penis and thus an erection. NO, nitrous oxide; PDE, phosphodiesterase, which metabolizes cGMP but is inhibited by sildenafil.

Invasive treatments are rarely satisfactory. Delicate and tedious arterial reconstructive procedures are usually disappointing, except in men with localized vascular injuries. Surgically implanted devices, such as rigid or semirigid silicone rods or a balloonlike apparatus, can mimic an erection. Unfortunately, implants are costly, unesthetic, and prone to infections and mechanical failures. In contrast, silicone penile implants have never been accused, like silicone breast implants, of causing rheumatologic or MS-like symptoms (see Chapter 15).

Underlying Conditions

Spinal Cord Injury

• Paraparesis or quadriparesis with spasticity, hyperactive reflexes, and Babinski signs

Poliomyelitis and Other Exceptions

For example, two relatively common motor neuron diseases, poliomyelitis (polio) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (see Chapter 5), devastate the voluntary motor system. Polio often left survivors confined to wheelchairs and braces, but with stable deficits. ALS, in contrast, causes progressively greater disability that usually results in death after several years. Nevertheless, both these illnesses spare victims’ intellect, sensation, involuntary muscle strength, and ANS functions. Thus, they allow patients normal sexual desire and function, genital sensation, bladder and bowel control, and fertility.

Similarly, most extrapyramidal illnesses (see Chapter 18), despite causing difficulties with mobility, do not impair sexual desire, sexual function, or fertility. For example, adolescents with athetotic cerebral palsy and other varieties of congenital birth injury – even those with marked physical impairments – often have intact libido and sexual function. Among older patients, those with Parkinson disease have preserved sexual drive; however, it may remain unexpressed until dopaminergic medications, such as levodopa and ropinirole, allow it to re-emerge. Moreover, neurologic conditions, such as frontal lobe trauma, frontotemporal dementia, and Alzheimer disease, that cause loss of inhibition sometimes lead to sexual aggressiveness.

Multiple Sclerosis

Sexual impairment can be the most bothersome and sometimes even the sole symptom of MS (see Chapter 15). Patients in an early stage of the disease may have few persistent neurologic deficits, but, as attacks recur, the incidence of sexual impairment rises. When sexual impairment occurs, urinary bladder dysfunction accompanies it in 90% of cases. MS-induced sexual impairment is also often associated with paresis and spasticity of the legs. Although spinal cord involvement probably underlies most cases of MS-induced sexual impairment, psychiatric comorbidity contributes. Whatever the precise mechanism, sexual dysfunction greatly reduces quality of life in MS patients and their partners.

Medication-Induced Impairment

Anticholinergic medications, which psychiatrists often prescribe to counteract antipsychotic medication-induced parkinsonism, also cause sexual impairment. In addition, these medicines cause other bothersome symptoms that reflect ANS dysfunction: dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, urinary hesitancy, and accommodation paresis (see Chapter 12). According to some studies, many antiepileptic drugs depress serum testosterone levels in men, which might impair their sexual function.

Priapism

Besides inducing pain, priapism can cause ischemia or, in severe cases, necrosis of the penis. Furthermore, repeated bouts lead to fibrosis. Urologists consider priapism an emergency. To stop blood flow into the penis, they inject it with epinephrine to produce arterial vasoconstriction (see Chapter 21). Cases that do not respond to epinephrine may require surgical drainage.

The Limbic System and the Libido

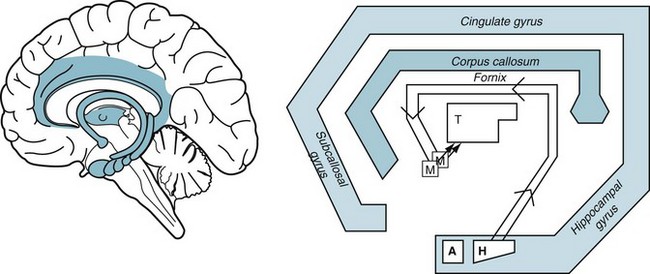

From a neurologic viewpoint, the limbic system provides libido. This system consists of a large horseshoe-shaped reverberating subcortical circuit that connects several structures: the hippocampal formation and the adjacent amygdala in the temporal lobe, thalamic and hypothalamic regions, including the mamillary bodies, midbrain nuclei, and frontal lobe (Fig. 16-5). Among its many functions, the limbic system generates, conveys, and stores memory, emotion, programs for “flight or fight,” eating and drinking behavior, and sexual and reproductive urges.

FIGURE 16-5 Left, The limbic system (shaded) is a circuit deep in the brain that connects with the overlying cerebral cortex. Right, This schematic portrayal of the limbic system shows its main features:

Structural lesions and neurodegenerative illnesses that strike the frontal or temporal lobes often damage the limbic system. For example, head trauma, strokes, or frontotemporal dementia (see Chapter 7) regularly reduce patients’ psychic energy, including their sexual appetite. Although most frontal lobe injuries cause apathy and hyposexuality, they occasionally lead to aggressive, sexually charged behavior.

The Klüver–Bucy Syndrome

In the classic laboratory model that produced the Klüver–Bucy syndrome, neurosurgeons performed bilateral anterior temporal lobectomies, which included removing both amygdalae (Greek, almond [the shape of the amygdalae]), on rhesus monkeys. Postoperatively, the animals displayed aggression and rampant, indiscriminate heterosexual and homosexual activity. In addition, as if they had lost their vision, the monkeys continually grasped objects and placed inedible as well as edible ones in their mouth. The investigators labeled this behavior psychic blindness or oral exploration (terms related to visual agnosia, see Chapter 12).

Other Conditions

Although complex partial epilepsy is usually associated with hyposexuality (see Chapter 10), its seizures sometimes induce activity with sexual overtones. For example, during a seizure, patients may tug at their clothing, partially undress, or even engage in rudimentary masturbation. However, the seizures do not cause frank, interactive sexual activity.

Disturbances in the hypothalamic–pituitary axis occasionally lead to decreased sexual activity. Hypothalamic tumors, for example, may induce a ravenous appetite, but without accompanying increased sexual activity. Also, the Kleine–Levin syndrome (see Chapter 17) includes increased rudimentary sexual activity, which is almost always masturbation, along with hypersomnia.

In contrast to those few examples of neurologic illnesses increasing sexuality, most decrease it. Lesions of the pituitary, hypothalamus, and diencephalon usually cause hyposexuality. For example, in Sheehan syndrome (see Chapter 19), women experience weight loss, amenorrhea, lack of sexual interest, and other symptoms of hypothalamic–pituitary insufficiency. Strokes with or without comorbid depression usually reduce both sexual interest and physical ability.

Neurologic Sequelae of Sexual Activity

Despite its pleasures, sexual activity occasionally produces several untoward neurologic consequences. In the simplest scenario, vigorous activity may precipitate a stroke because of exercise-induced hypertension or herniate a lumbar intervertebral disk because of low back strain. A migraine-like headache during sex (coital cephalalgia, see Chapter 9) occasionally occurs. In a rare but more worrisome scenario, a powerful “thunderclap” headache during sex sometimes signals the onset of a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Thus, when sexual activity precipitates a unique headache, neurologists generally recommend further evaluation, including magnetic resonance imaging and angiography, as the first step in identifying an aneurysm. Whether sexual activity produces a cardiac arrhythmia, hypertension or, because of a Valsalva maneuver, hypotension, it may cause an episode of transient global amnesia (see Chapter 11).

Basu A, Ryder RE. New treatment options for erectile dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2004;64:2667–2688.

Baum N, Essell A. Treating erectile dysfunction in nonresponders to PDE5 inhibitors. Res and Staff Phys. 2008;54:20–25.

Carey JC. Pharmacological effects on sexual function. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:599–620.

Compton MT, Miller AH. Priapism associated with conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications: A review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:362–366.

Compton MT, Miller AH. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia and sexual function. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36:143–164.

Fowler CJ, Miller JR, Sarief MK, et al. A double blind, randomized study of sildenafil citrate for erectile dysfunction in men with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:700–705.

Frohman EM. Sexual dysfunction in neurologic disease. Clin Neuropharm. 2002;25:126–132.

Harden C. Sexuality in men and women with epilepsy. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(Suppl 9):13–28.

Herzog AG, Drislane FW, Schomer DL, et al. Differential effects of antiepileptic drugs on neuroactive steroids in men with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1945–1948.

Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1802–1813.

Montgomery SA, Baldwin DS, Riley A. Antidepressant medications: A review of the evidence for drug-induced sexual dysfunction. J Affective Disord. 2002;69:119–140.

Mota M, Lichiardopol C, Mota E, et al. Erectile dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Rom J Intern Med. 2003;41:163–177.

Rudkin L, Taylor MJ, Hawton K. Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2004. CD003382

Smith SM, O’Keane V, Murray R. Sexual dysfunction in patients taking conventional antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:49–55.

Webber R. Erectile dysfunction. Clin Evid. 2004;11:1148–1157.

Chapter 16 Questions and Answers

5. Immediately after sexual intercourse with his wife of almost 40 years, a retired baseball player seemed to forget his whereabouts and the events of the previous several hours, which included his 65th birthday party. When his wife brought him to the emergency room, he could not recall the name of the physician, despite three introductions, or a list of three objects; however, he recalled his age, telephone and Social Security numbers, and the names and birthdays of all his family members. He became frustrated, anxious, and distressed. A neurologist found no physical deficits. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

10. One month after falling down a flight of stairs, a 35-year-old man complains of low back pain and erectile dysfunction. Examination reveals loss of pinprick sensation below the waist, but intact position, vibratory, and warm–cold sensation. Deep tendon and cremasteric reflexes are intact, and plantar reflexes are flexion. Which is the most likely cause of the erectile dysfunction?

22. Which of the following sequences describes the path of the limbic system?

30. Which of the following statements concerning α-adrenergic agonists and antagonists is false?

31. A 48-year-old man, under treatment with an SSRI for depression, complains that he has developed erectile dysfunction. On the other hand, he reports that he is pleased that the SSRI has greatly improved his mood and energy level, and he has returned to work and resumed a social life. What would be the best treatment for the erectile dysfunction?

32. A 49-year-old man, with diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, had described having erectile dysfunction. His primary care physician had prescribed a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. Although the medicine produced satisfactory erections, he developed postcoital severe throbbing headaches and on several occasions postcoital fainting. He returned very discouraged. Which of the following medicines would be best next step?