Chapter 14 Neurologic Aspects of Chronic Pain

Pain Varieties

Unlike the dull ache of nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain consists of electric, sharp, lancinating, or burning sensations. Also, not confined to the site of tissue injury, neuropathic pain and spontaneously occurring painful paresthesias radiate throughout the distribution of the injured nerve and often well beyond it. Other features are that painful or even neutral stimuli elicit an intense, distorted, or prolonged response – allodynia, hyperalgesia, and hyperpathia (see Chapter 5).

Pain Pathways

Central Pathways

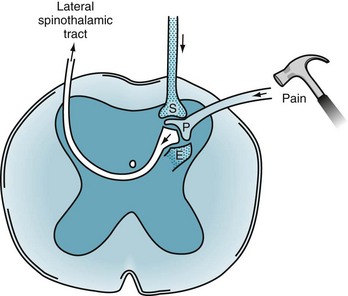

The PNS fibers enter the CNS at the spinal cord’s dorsal horn and, either immediately or after ascending a few segments, synapse in its substantia gelatinosa (Fig. 14-1). At many of these synapses, the fibers release an 11-amino-acid polypeptide, substance P, which constitutes the major neurotransmitter for pain at the spinal cord level.

FIGURE 14-1 Painful sensations travel along the peripheral nerves’ A delta and C fibers. These fibers enter the dorsal horn of the spinal cord where, using substance P (P), they synapse on to second-order neurons. The second-order neurons cross to the contralateral side of the spinal cord and, forming the lateral spinothalamic tract, ascend to the thalamus. Two powerful pain-dampening or pain-modulating analgesic systems (stippled) play upon the dorsal horn synapse. One tract descends from the brain and releases serotonin (S). The other system is composed of spinal interneurons that release enkephalins (E).

After the synapse, pain sensation ascends predominantly within the lateral spinothalamic tract to the brain (see Figs 2-6 and 2-15). This crucial tract crosses from the substantia gelatinosa to the spinal cord’s other side and ascends, contralateral to the injury, to terminate in specific thalamic segments. Additional synapses relay the stimuli to the somatosensory cerebral cortex, enabling the individual to locate the pain.

Analgesic Pathways

Many analgesic pathways interfere with pain transmission within the brain or spinal cord. Several pathways that originate in the frontal lobe and hypothalamus terminate in the gray matter surrounding the third ventricle and aqueduct of Sylvius (periaqueductal gray matter). They contain large amounts of endogenous opioids, which are powerful analgesics (Box 14-1). Implanted electrodes that stimulate the periaqueductal gray matter area may provoke the release of endogenous opioids and thereby induce profound analgesia.

Box 14-1

Glossary

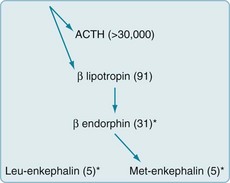

β-endorphin: An endogenous opioid concentrated in the pituitary gland and secreted with ACTH. It consists of amino acid numbers 61–91 of β-lipotropin and gives rise to the enkephalins (see Fig. 14-2)

β-lipotropin: A 91-amino-acid polypeptide, which may be an ACTH fragment. It gives rise to β-endorphin but has no opioid activity itself (that is, β-lipotropin is not an endogenous opioid)

Dynorphin: An endogenous peptide opioid that binds to kappa opioid receptors

Endogenous opioids: Polypeptides (amino acid chains) found within the central nervous system that create effects similar to those of morphine and other opioids. The effects of both endogenous and exogenous opioids are characteristically reversed by naloxone

Endorphins: Endogenous morphine-like substances or opioid peptides. This term is virtually synonymous with endogenous opioids

Enkephalins: Short (5-amino-acid) polypeptide endogenous opioids that include met-enkephalin and leu-enkephalin. They are found primarily in the amygdala, brainstem, and dorsal horn of the spinal cord

Naloxone (Narcan): A pure opioid antagonist that reverses the effects of endogenous and exogenous opioids

Substance P: An 11-amino-acid polypeptide that is probably the primary pain neurotransmitter at the first synapse of the primary afferent neuron in the spinal cord

Endogenous Opioids

Often called endorphins (endogenous morphine-like substances), endogenous opioids – endorphins, enkephalins, and dynorphins – are powerful analgesic, amino-acid chains (polypeptides) synthesized in the CNS (Fig. 14-2). Endogenous opioids bind to receptors in the limbic system, periaqueductal gray matter, dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and other CNS sites. Neurologists commonly say that a “runner’s high” and the initial painlessness reported by wounded soldiers serve as examples of endorphins’ analgesic effects.

FIGURE 14-2 Endogenous opioids are synthesized and secreted, along with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), from the pituitary gland in times of stress or acute pain. A large precursor molecule (not pictured) gives rise to ACTH and β-lipotropin, which are often released together. β-lipotropin gives rise to β-endorphin and met-enkephalin, but another precursor gives rise to leu-enkephalin. (The asterisks denote the important endogenous opioids, and the numbers within parentheses are the amino acid units in the polypeptide chains.)

Treatments

Nonopioid Analgesics

As previously mentioned, aspirin, other salicylates, NSAIDs, steroids, and acetaminophen – nonopioid analgesics – inhibit prostaglandin synthesis at the injury (Box 14-2). Through this mechanism, these medicines relieve acute and chronic pain of mild to moderate severity.

Box 14-2

Examples of Analgesics

Nonopioid analgesics generally provide steady analgesia for weeks to months and avoid several potential problems. In particular, after completing a course of treatment, patients do not experience withdrawal symptoms. Also, except for high-dose steroids potentially causing steroid psychosis (see Chapter 15), these analgesics do not induce mood, cognitive, or thought disorders.

Opioids

When chronic pain results from cancer, neurologists categorize it as “cancer” or “malignant” pain, but when it results from other conditions, “noncancer” pain. Opioids are unquestionably indicated for cancer pain (see Box 14-2). In addition, a number of studies suggest that they are indicated for chronic noncancer pain syndromes.

Other Opioid Side Effects

To prevent or alleviate opioid-related nausea, physicians should prescribe antiemetics, but they should cautiously prescribe antiemetics containing phenothiazine or other dopamine-blocking agent because they can cause dystonic reactions or parkinsonism (see Chapter 18). In another caveat, pharmacologic marijuana, such as dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone (Cesamet), generally reduces nausea, pain, and anxiety; however, robust formal studies have not established that they are the most effective treatment when cancer or chemotherapy has been responsible for these symptoms. Moreover, they may cause transient mood and thought disorders.

As with other medicines, physicians should discontinue opioids when unnecessary. Rather than abruptly stopping opioids, which would probably lead to withdrawal, physicians might use an exit strategy of tapering opioids by reducing their dose by 50% every 3 days. Alternatively, physicians might briefly replace a short-acting opioid, such as morphine, with a long-acting one, such as methadone, and then prescribe a nonopioid analgesic. If withdrawal still complicates the process, benzodiazepines may alleviate the physical or mental discomfort, and clonidine (Catapres) may blunt autonomic nervous system hyperactivity (see Chapter 21).

Chronic Opioid Therapy Debate

Physicians who have opposed expanding opioid prescription offer several counterarguments. Opioids reduce pain less than 2–3 points on a 0–10 scale. Chronic opioid therapy may be counterproductive in several conditions. It portends worse long-term outcomes for headache and low back pain, and tends to convert episodic migraines or tension-type headache to persistent daily headache (see Chapter 9). Patients demand opioids when less potent or alternative measures, even nonpharmacologic ones, would suffice. In addition, patients may subvert medical treatment. They may seek opioids for their euphoric effect rather than for pain relief. Falsely reporting the persistence and severity of pain to obtain opioids, patients prolong their disability. Some patients, claiming intractable pain, demand excessive quantities, but sell or pass along their opioids. To avoid this “diversion” of opioids, some physicians go so far as to ask the patient who has been prescribed fentanyl patches to return the used ones, which should have the patient’s hair stuck to the patch’s adhesive. Some patients use opioids to tide them over an addiction to illicit drugs. For many patients, obtaining opioids takes over their day-to-day concerns.

Other Treatments Directed at the Peripheral or Central Pathways

To interrupt pain transmission in the spinal cord, physicians have introduced several different treatments. Capsaicin cream, applied to a painful area, is absorbed through the skin and drawn up along sensory nerves. When it reaches the spinal cord synapse, capsaicin depletes substance P, the crucial neurotransmitter, and thereby impairs pain transmission (see Fig. 14-1). This treatment, which complements systemic medicines, helps alleviate pain from arthritis, diabetic neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralgia.

Stimulation-Induced Analgesia

Along the same line, some studies found that acupuncture provides analgesia in people with mild to moderate pain. Placing the needles in dermatomes (see Fig. 16-2) creates more analgesia than placing them in the traditional regions (meridians). When acupuncture includes electrostimulation, the procedure doubles its effectiveness. Because traditional acupuncture induces a rise in brainstem, limbic system, and cerebrospinal fluid endorphins and its benefit is naloxone-reversible, acupuncture may work in part through the endogenous opioid system (Box 14-3).

Epidural Analgesia

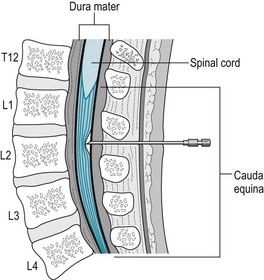

Anesthesiologists administer epidural analgesia, an epidural, for vaginal birth, cesarean section, or other pelvic surgical procedures. Epidurals anesthetize nerve roots T10 through L1, which innervate the uterus and cervix, and S2–4, which, through the pudendal nerves, innervate the vaginal canal and perineum (see Fig. 16-1). They create analgesia throughout the pelvis, but do not cause respiratory depression in the woman or affect the fetus.

The procedure typically consists of the anesthesiologist introducing a catheter into the lumbar epidural space and injecting a local anesthetic, such as lidocaine, along with an opioid anesthetic, such as morphine (Fig. 14-3). The anesthetics permeate the lumbosacral epidural space, but, to a limited extent, they also diffuse into the underlying subarachnoid space. Depending on the duration of the procedure, required depth of analgesia, and other factors, the anesthesiologist continually administers anesthetics through the catheter. When the anesthetic bathes only the lowermost nerves, as for delivery and other obstetric procedures, patients retain strength in their legs and remain able to walk.

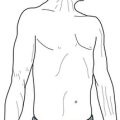

FIGURE 14-3 To administer an epidural anesthetic or steroid preparation, the physician advances a needle through the subcutaneous tissue into the lumbar epidural space and sometimes then passes an indwelling catheter over or through the needle. The lumbar and sacral nerve roots run through this space, where the medicines bathe them. This injection, at the L2 level, is comfortably below the spinal cord, which terminates at T12–L1, and outside the subarachnoid space.

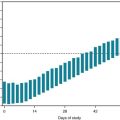

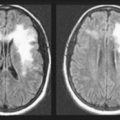

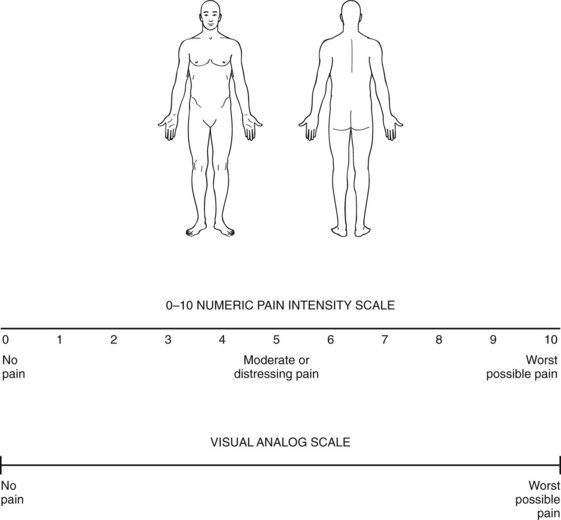

Cancer Pain

Physicians should generally accept patients’ accounts of their pain without reservation and monitor their pain as regularly as they check the temperature and pulse (Fig. 14-4). In fact, pain has come to be regarded as the “fifth vital sign.” Patients should have access to nonpharmacologic treatments as well as the full arsenal of medicines. Physicians should prescribe medicines from the three categories – nonopioid, opioid, and adjuvant – early, if not pre-emptively, and then frequently and generously. As opioid tolerance develops, physicians should readily increase the doses. In addition, they should suppress “breakthrough pain” with supplements to regularly scheduled opioids.

FIGURE 14-4 Graphics are replacing verbal reports of the site and severity of pain. Patients describe their pain by circling the most painful area on the sketch. Then they circle the single number on the numeric pain scale or mark the visual analog scale at the point that describes the intensity of their pain. Most children 8 years or older can use the analog scale. Physicians for children as young as 3 years may substitute the Wong–Baker smiling/crying faces icons. Although useful for assessing acute pain intensity, these scales are literally one-dimensional and fail to capture suffering, functional impairment, insomnia, or changes in mood. Moreover, they do not allow the patient to describe symptoms of neuropathic pain, such as allodynia.

(Adapted from Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R, et al. Management of Cancer Pain: Adults’ Quick Reference Guide No. 9. AHCPR Publication No. 94-0593. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 1994.)

Noncancer Pain Syndromes

The book has already reviewed several common noncancer pain syndromes, including diabetic neuropathy (see Chapter 5) and trigeminal neuralgia (see Chapter 9). This chapter continues by discussing six others. Their pharmacologic management often begins with analgesics, which often includes chronic opioids. TCAs, SNRIs, gabapentin, and pregabalin are more effective in the treatment of neuropathic than nociceptive pain. Patients may still require opioids. Physical and occupational therapy, psychotherapy, hypnosis, behavioral therapies, and social service intervention may further reduce suffering, improve mobility, and increase function.

Low Back Pain

As opposed to acute low back pain from a herniated intervertebral disk (see Chapter 5), chronic low back pain seems to stem from ill-defined or nonspecific injury of the lumbar vertebrae, intervertebral disks, or the supporting ligaments. Affecting over 2 million individuals, chronic low back pain is one of the most prevalent disabling conditions in the United States.

Abramowicz M. Medical marijuana. Med Lett. 2010;52:5–6.

Backonja MM, Krause SJ. Neuropathic pain questionnaire – short form. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:315–316.

Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1943–1953.

Bartleson JD. Evidence for and against the use of opioid analgesics for chronic nonmalignant low back pain: A review. Pain Med. 2002;3:260–271.

Benarroch EE. Sodium channels and pain. Neurology. 2007;68:233–236.

Berman BM, Langevin HH, Witt CM, et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:454–461.

Carragee EJ. Persistent low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1891–1898.

Carragee EJ, Alamin TF, Miller JL, et al. Discographic, MRI, and psychosocial determinants of low back pain disability and remission: A prospective study in subjects with benign persistent back pain. Spine J. 2005;5:24–35.

Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Cote P. Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain. Pain. 2004;107:134–139.

Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Deyo R, et al. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy, and spinal manipulation for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:898–906.

Diers M, Christmann C, Koeppe C, et al. Mirrored, imagined and executed movements differentially activate sensorimotor cortex in amputees with and without phantom limb pain. Pain. 2010;149:296–304.

Dubinsky RM, Miyasaki J. Practice parameter: Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Neurology. 2004;63:959–965.

Dubinsky RM, Kabbani H, El-Chami Z, et al. Assessment: Efficacy of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation in the treatment of pain in neurologic disorders (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2010;74:173–176.

Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(3 Suppl):S3–S14.

Foley KM. Opioids and chronic neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1279–1281.

Hawkins JL. Epidural analgesia for labor and delivery. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1503–1510.

Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, et al. Meta-analysis: Exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:765–775.

Jovey RD, Ennis J, Gardner-Nix J, et al. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain – a consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Res Manag. 2003;Suppl A:3A–28A.

Jung BF, Ahrendt GM, Oaklander S, et al. Neuropathic pain following breast cancer surgery. Pain. 2003;104:1–13.

Nasreddine ZS, Saver JL. Pain after thalamic stroke: Right diencephalic predominance and clinical features in 180 patients. Neurology. 1997;48:1196–1199.

Nicholson B, Passik SD. Management of chronic noncancer pain in the primary care setting. South Med J. 2007;100:1028–1036.

Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systemic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine. 2002;27:109–120.

Rowbotham MC, Twilling L, Davies PS, et al. Oral opioid therapy for chronic peripheral and central neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1223–1232.

Sampathkumar P, Drage L, Martin D. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274–280.

Slipman CW, Shin CH, Patel RK, et al. Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med. 2002;3:200–214.

Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients. Pain Med. 2005;6:432–442.

Williams LS, Jones WJ, Shen J, et al. Outcomes of newly referred neurology outpatients with depression and pain. Neurology. 2004;63:674–677.

27. A 39-year-old headache patient, who has had migraine since childhood, has been taking an aspirin–butalbital–caffeine compound (Fiorinal) daily for at least 10 years. When the patient attempts to stop the medication, unbearable generalized dull headaches develop. What is the best descriptive term for this phenomenon?

b. Headaches following withdrawal of analgesics, especially if they are combined with vasoconstrictive medications, represent a major problem in headache management. “Medication overuse headache” is a form of withdrawal (see Chapter 9).

38. A passing automobile catches the shirtsleeve of a 40-year-old man. The force drags him by the arm and dislocates his shoulder. Even after the shoulder has apparently healed, the entire arm develops an intense burning sensation that increases on movement or touching. The patient avoids using the arm and often wears a glove. The skin of the hand becomes smooth, dry, and edematous. He cannot cut his fingernails because the pain is too intense. Which of the following three statements are true concerning this condition?

c. Requiring additional doses of a substance is termed tolerance.

41. Match the term with the closest description. More than one answer may be appropriate.

47. After incessant low back pain ended the successful career of a screen actor at the age of 65 years, he went through a series of surgical procedures on his lumbar spine for herniated disks and degenerative changes. Physical therapy and psychotherapy provided little relief. By prescribing opioids, adjuvant medications, and physical therapy, his pain management physicians controlled his pain and returned him to parttime work making radio commercials. Several months later, his physicians found that he was requiring increasing doses of opioids to maintain his improvement. Suspecting drug abuse, they sent him for a psychiatric consultation. Which of the following conditions is least likely to explain his increased demand for opioids?

48. A Gulf War veteran, who had lost both legs and his genitalia, was in a methadone maintenance program partly as pain control and partly to prevent his returning to street narcotics. His psychiatrist was prescribing an SSRI as well as providing supportive psychotherapy. One night he was left in the emergency room where physicians found him comatose, almost apneic, and with miotic pupils. He was in pulmonary edema. Which would be the best immediate treatment?

54. An 80-year-old man sustains a cerebral infarction that initially causes loss of almost all sensation on the left face, trunk, and limbs. Several weeks later, the sensory loss recedes but is replaced by continual burning pain in the left face and arm. Also, the slightest stimulation, including people brushing against his hand or physicians examining it, causes intolerable pain. He carefully shields the hand and arm under a glove and covers his arm with a blanket. What is the name of this condition?