76 Neurocutaneous Disorders

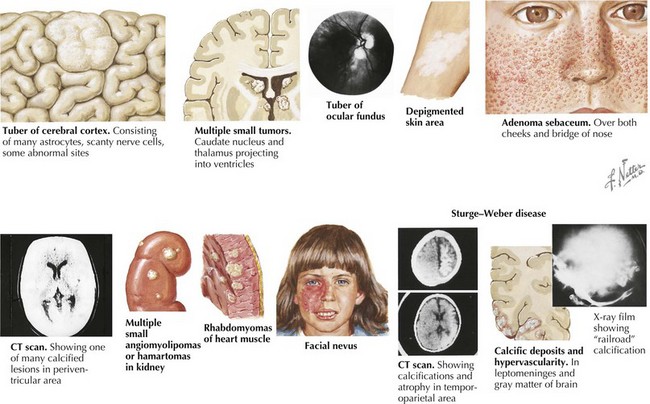

Tuberous Sclerosis

TSC is a multisystemic disorder involving the eyes, heart, lung, kidney, brain, and skin (Figure 76-1). The prevalence of TSC is one in 6000 to 10,000 live births. TSC is caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in TSC 1 on chromosome 9q34 or TSC 2 gene on chromosome 16p13. TSC can result from inherited or de novo mutations. TSC 1 and 2 code for hamartin and tuberin, respectively, which form a protein complex involved in the regulation of cell growth. In TSC, there is loss of inhibition of Rheb (a rapamycin) by TSC 1–TSC 2 complex leading to uncontrolled cell growth of hamartomas in multiple organ systems. The diagnosis of TSC is based on clinical findings, and genetic testing is corroborative. The TSC Consensus Conference in 1998 revised the diagnostic criteria (Table 76-1); a patient must have two major features, or one major and two minor features. A patient with one major and one minor feature is diagnosed with probable TSC.

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|

| Facial angiofibromas or forehead plaque | Multiple randomly distributed dental enamel |

| Nontraumatic ungual or periungual fibroma | Hamartomatous rectal polyps |

| Hypomelanotic macules (>3) | Bone cysts |

| Shagreen patch (connective tissue nevus) | Cerebral white-matter “migration tracts” |

| Cortical tuber | Gingival fibromas |

| Subependymal nodule | Retinal achromic patch |

| Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma | Nonrenal hamartoma |

| Multiple retinal nodular hamartomas | “Confetti” skin lesions |

| Cardiac rhabdomyoma (single or multiple) | Multiple renal cysts |

| Lymphangiomyomatosis | |

| Renal angiomyolipoma |

From Roach ES, DiMario FJ, Kandt RS, et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference: recommendations for diagnostic evaluation. J Child Neurol 14:401-407, 1999.

Table 76-2 shows the tests and surveillance recommended for TSC.

Table 76-2 Tests and Surveillance Recommended for Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

| Assessment | Initial Testing | Frequency of Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Brain imaging: MRI or CT scan | At diagnosis | Every 1–3 years |

| Renal ultrasound | At diagnosis | Every 1–3 years |

| Ophthalmic examination | At diagnosis | As indicated |

| Neurodevelopmental testing | At diagnosis | As indicated |

| EKG | At diagnosis | As indicated |

| ECHO | At diagnosis | As indicted |

| EEG | If seizures are present | As indicted |

| Chest CT | In adulthood (women only) | As indicated |

CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiography; ECHO, echocardiography; EEG, electroencephalography.

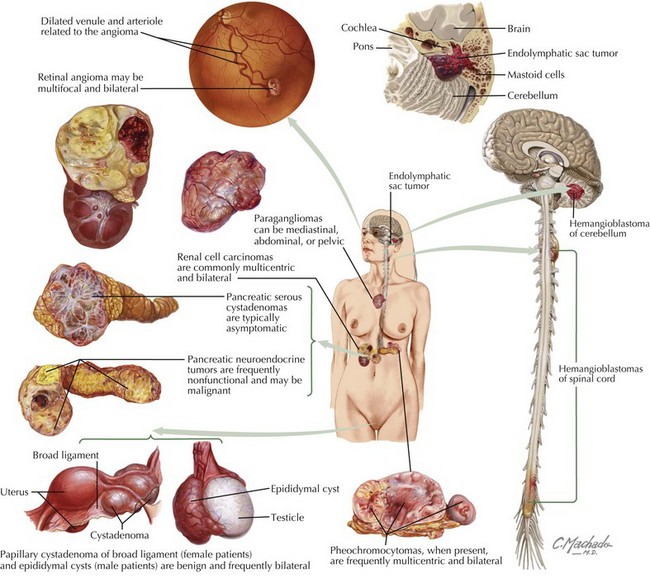

Von Hippel–Lindau Disease

VHL disease is a neurocutaneous disorder with benign and malignant tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), retina, ear, and pancreas. The prevalence is one in 39,000 live births. The inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant involving the VHL gene on chromosome 3p25, which codes for a tumor suppressor protein. The disease may also result from de novo mutations. According to the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Cancer Risk Analysis and VHL Center, patients should be screened for VHL disease if they have a blood relative with VHL disease, have a VHL disease–associated tumor and a family history of VHL disease–associated tumors, or have two or more VHL disease–associated lesions. VHL disease–associated lesions include hemangioblastoma, clear cell renal carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, middle ear endolymphatic sac tumor, epididymal papillary cystadenoma, pancreatic serous cystadenoma, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (Figure 76-2). Individuals with clinical features listed in Box 76-1 should be screened for VHL.

There are many different tumors seen with VHL disease. Table 76-3 shows tests and screening recommended for VHL disease. RCC (clear cell type) is the highest mortality risk factor associated with VHL disease. It rarely develops before 20 years of age. Renal tumors greater than 3 cm are surgically excised. Patients present with hematuria, flank pain, or a palpable mass. Pheochromocytomas are associated with VHL in childhood. They are often asymptomatic with no clinical evidence of increased blood pressure. Endolymphatic sac tumors are papillary cystadenomas located within the posterior temporal bone. These lesions have an extensive vascular supply. Children present with hearing loss, vertigo, nystagmus, and facial muscle weakness. Treatment is surgical. Pancreatic lesions include cysts and serous cystadenomas, which are surgically excised when larger than 3 cm. VHL disease is also associated with asymptomatic papillary cystadenomas of the epididymis and broad ligament.

Table 76-3 Tests and Screening Recommended for von Hippel–Lindau Disease

| Tumor Associated with von Hippel–Lindau Disease | Age Range for Screening | Tests or Screening Performed Yearly |

|---|---|---|

| Retinal hemangiomas | Infancy to adulthood | Eye examination |

| Pheochromocytomas | Infancy to adulthood >11 years old to adulthood |

Plasma normetanephrine Abdominal CT |

| Hemangioblastomas | >11 years old to adulthood | MRI with and without contrast of brain and spinal cord |

| Renal tumors and pancreatic tumors | >16 years to adulthood | Abdominal MRI or US |

| Endolymphatic sac tumors | At onset of symptoms or adulthood | ENT evaluation and MRI or CT or the internal auditory canal |

CT, computed tomography; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound.

From Maher ER, Neumann HPH, Richard S. Hippel-Lindau disease: A clinical and scientific review. Eur J Human Genetics Mar 9, 2011, 1-7.

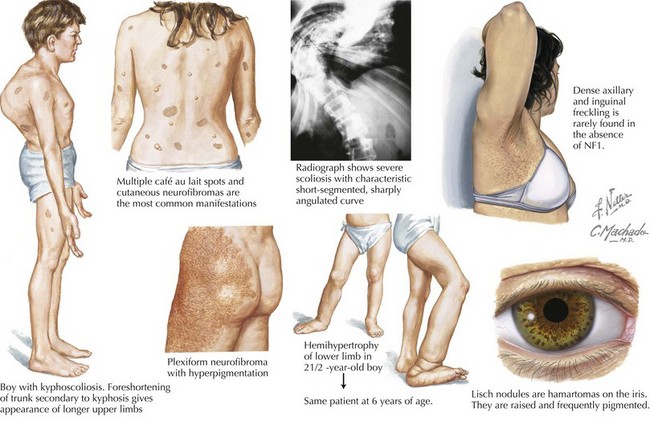

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and 2

The inheritance pattern of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) is autosomal dominant. The disease is caused by a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17, which encodes for neurofibromin. It is the most common neurocutaneous disorder (incidence of one per 3000 individuals). To make the diagnosis of NF-1, the patient must have at least two of the criteria shown in Table 76-4.

| Café-au-lait spots | ≥6 lesions that are >5 mm in prepubertal individuals and >15 mm in postpubertal individuals |

| Neurofibromas | ≥2 neurofibromas of any type (including subcutaneous neurofibromas) or 1 plexiform neurofibroma |

| Freckling | In the axillary or inguinal region |

| Optic glioma, melanocytic iris hamartomas (also known as Lisch Nodules) | ≥2 |

| Bony lesion | Such as sphenoid dysplasia, thinning of the long bone cortex, scoliosis |

| First-degree family history of NF-1 |

NF, neurofibromatosis.

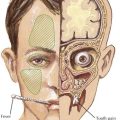

Neurofibromas are benign Schwann cell tumors of the peripheral nervous system. The subcutaneous and cutaneous neurofibromas may be asymptomatic, cause cosmetic deformity, or cause pruritus or pain (Figure 76-3). Spinal neurofibromas cause sensory and motor deficits. Plexiform neurofibromas involve multiple nerve fascicles and grow along the length of the nerve. They may invade surrounding tissue (muscle, bone, and internal organs). Plexiform neurofibromas cause pain and neurologic deficits. They may transform into spindle cell sarcomas or malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, which have a poor prognosis. Optic gliomas occur in approximately 15% to 25% of patients with NF-1 during childhood. Patients present with visual acuity impairment, visual field loss, optic disc swelling, strabismus, or proptosis. NF-1 is also associated with moyamoya disease (vascular abnormality within the brain), cardiac malformations, and renal arterial stenosis. NF-1 patients may have mild behavior and cognitive difficulties. Treatment management involves analgesics for the pain associated with neurofibromas, symptomatic neurofibroma resections by soft tissue surgeons and neurosurgeons, yearly evaluations for scoliosis, annual ophthalmologic examinations for optic pathway gliomas, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) surveillance scans for diagnosed gliomas, hypertension management, and orthopedic surgery for bone deformities.

Butman JA, Linehan WM, Lonser RR. Neurologic manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1334-1342.

Comi A. Topical review: pathophysiology of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:509-516.

Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. Medical progress: the tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):345-1356.

Ferner RE. Neurofibromatosis type 1 and neurofibromatosis type 2: a twenty-first century perspective. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:340-351.

Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:189-198.

Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2059-2067.

Maher ER, Neumann HPH, Richard S. Hippel-Lindau disease: A clinical and scientific review. Eur J Human Genetics. Mar 9, 2011:1-7.

Roach ES, DiMario FJ, Kandt RS, et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference: recommendations for diagnostic evaluation. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:401-407.

Roach ES, Sparagana SP. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(9):643-649.

Thomas-Sohi KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30(5):303-310.

Umeoka S, Koyama T, Miki Y, et al. Pictorial review of tuberous sclerosis in various organs. RadioGraphic. 2008;28(7):e32.

Williams VC, Lucas J, Badcock MA, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics. 2009;123:124-133.