58 Neuroblastoma

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Additionally, a number of genetic aberrations are important in classification and prognosis of neuroblastoma. The DNA content of tumor cells is characterized as near-diploid or hyperdiploid, the latter of which is associated with a more favorable outcome. Examples of other genetic abnormalities associated with prognosis include MYCN amplification, deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1p, and deletion of chromosome 11q. The most important of these, MYCN amplification, is associated with rapid tumor progression and poor prognosis, even in patients with otherwise lower stage disease. Neuroblastoma is most commonly an isolated diagnosis, but it has been associated with other neurocristopathies such as Hirschsprung’s disease, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS or Ondine’s curse), and neurofibromatosis type 1. Additionally, a very small number of patients (1%-2%) present as part of a familial neuroblastoma syndrome. In this situation, the most common genetic abnormality is a germline mutation in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene (Figure 58-1).

Clinical Presentation

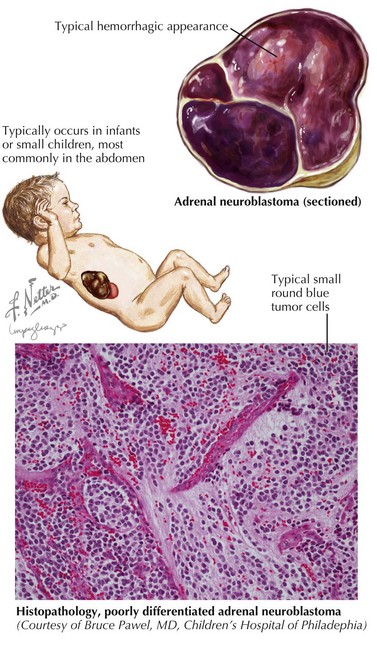

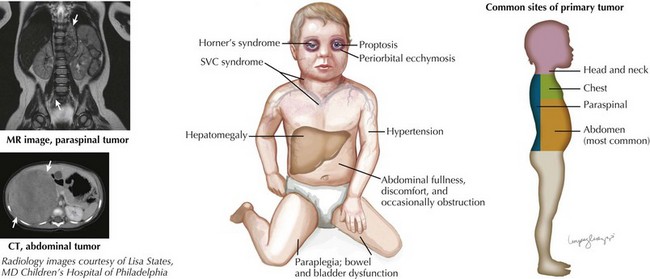

Neuroblastoma can arise anywhere along the sympathetic chain, and symptoms at the time of diagnosis depend on the location and extent of disease. Primary tumors most commonly occur in the abdomen (65%) and usually present as a painless abdominal mass. These patients may also present with vomiting, constipation, or symptoms of intestinal obstruction. Other common sites of primary tumors include the neck, chest, and paraspinal region. Tumors arising from the chest may be found incidentally on chest radiography, and cervical tumors may present as a Horner’s syndrome or more rarely with superior vena cava syndrome (Figure 58-2).

A small percentage of children (5%) present with symptoms of spinal cord compression. This oncologic emergency is associated with paraspinal neuroblastomas, and associated findings include lower extremity weakness, bowel and bladder dysfunction, back pain, and sensory loss. Neurologic function at the time of diagnosis has a strong association with long-term neurologic outcome (see Figure 58-2).

Differential Diagnosis

Because of its varied presentation, the differential diagnosis of a patient with suspected neuroblastoma is broad and should be based on specific signs and symptoms. The clinical presentation can be divided into categories: an abdominal mass or symptoms, a mass in another location, spinal cord compression, and nonspecific neurologic symptoms. Table 58-1 summarizes the differential diagnosis of neuroblastoma using these categories of presenting symptoms.

| Abdominal Mass | ||

|---|---|---|

| Intraabdominal mass | Neuroblastoma | Ovarian torsion |

| Wilms tumor | Ovarian tumor | |

| Omphalocele | Teratoma | |

| Hernia | Lymphoma | |

| Pheochromocytoma | Hepatoblastoma | |

| Adrenal hemorrhage | Pancreatoblastoma | |

| Hemangioendothelioma | ||

| Intestinal mass | Bezoar | Intussusception |

| Volvulus | Abscess | |

| Megacolon | ||

| Other intraabdominal pathologies | Pancreatic pseudocyst | Enlarged uterus |

| Choledochal cyst | Constipation | |

| Hydrops of the gallbladder | Cystic kidney disease | |

| Thoracic Mass | ||

| Oncologic | ||

There are many causes of spinal cord compression (see Table 58-1) in addition to neuroblastoma. However, in the case of spinal cord compression, the cause may not be immediately known, and steroid treatment can be initiated before a definitive diagnosis is made in select cases. In cases in which neurologic symptoms are rapidly progressing, immediate treatment is warranted to increase the prospect for preservation of neurologic function.

Staging and Management

Staging

The treatment approaches for neuroblastoma depend on a number of clinical and biologic characteristics of the tumor. Tumor risk assessment, as devised by the International neuroblastoma Risk Group, depends on tumor stage, age at diagnosis, and MYCN gene status. These factors along with other biologic variables (mainly genetic aberrations) and tumor histology are used to classify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories. Tables 58-2 and 58-3 summarize tumor staging and risk stratification. Risk stratification (shown in a simplified form here) is essential in determining a treatment course and prognosis for patients with neuroblastomas.

Table 58-2 International Neuroblastoma Staging System (Simplified)

| 1 | Localized tumor with complete gross resection |

| 2A | Localized tumor with incomplete resection and gross residual disease; ipsilateral lymph nodes without tumor cells |

| 2B | Localized tumor with or without complete resection and ipsilateral lymph nodes positive for tumor cells |

| 3 | Unresectable tumor extending across the midline (directly or via nodal extension) |

| 4 | Any primary tumor with dissemination to distant lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, liver, skin, or other organs (except 4S) |

| 4S | Localized primary tumor (1, 2A, or 2B) in infants younger than 1 year old with dissemination limited to skin, liver, or bone marrow |

Table 58-3 Risk Stratification (Simplified)

| Risk Group | Stages Included | Treatment Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Low risk |

Brodeur GM, Maris JM. Neuroblastoma. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 2006:933-970.

Maris JM, Hogarty M, Bagatell R, et al. Neuroblastoma: a review. Lancet. 2007;369:2106-2120.

Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, et al. Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation, and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children’s Cancer Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1165-1173.