Nervous System

Disorders of the Motor Neuron, Peripheral Nerve, Neuromuscular Junction, and Skeletal Muscles

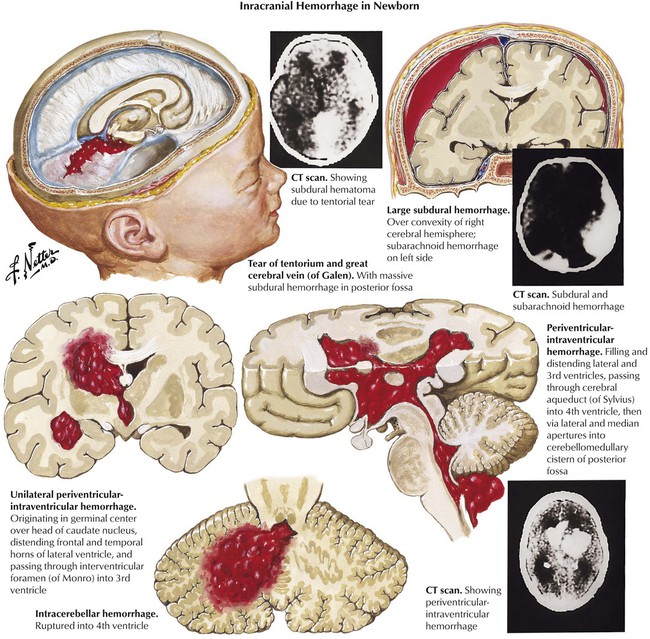

In the newborn, certain forms of intracranial hemorrhage are usually related to birth trauma, and these include subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and posterior fossa hemorrhage. However, other factors, particularly prematurity and asphyxia, are involved in periventricular and intraventricular hemorrhage. Periventricular-intraventricular hemorrhage originates in the germinal matrix and occurs with increasing frequency in relation to the degree of prematurity of the infant. Such bleeding causes a high mortality rate. Surviving infants often develop cerebral palsy.

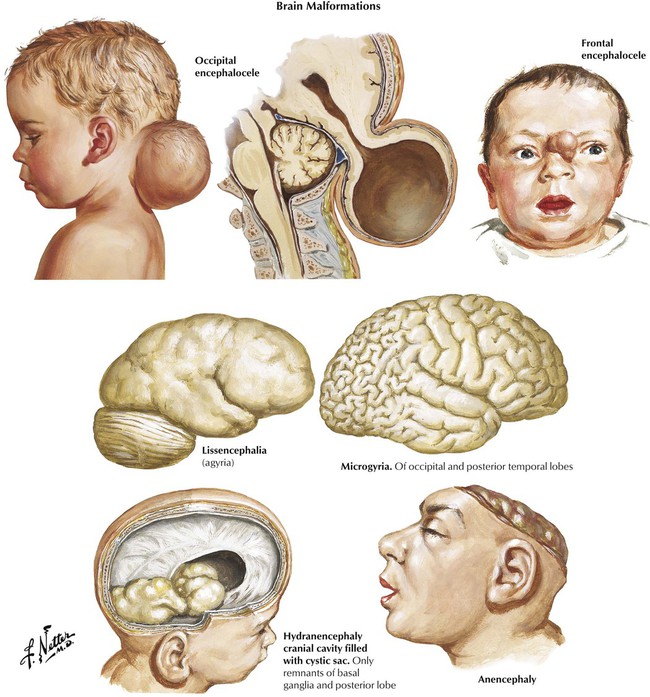

The time of onset of prenatal injury predicts the type of maldevelopment and resultant prenatal encephalopathy characterized by defects in the formation of the neural tube (first trimester), neural proliferation and migration (second trimester), and neural organization and myelination (third trimester). Defects in neural tube formation in the first trimester result in anencephaly, encephalocele, or holoprosencephaly (arrhinencephalia), the latter characterized by a single ventricle with defective olfactory and optic systems, and impairment of caudal closure results in meningomyelocele. During the phase of neuronal proliferation, a decrease in number of neurons leads to microcephaly, whereas an increase results in megalencephaly. With defective neuronal migration, gyral formation does not occur, resulting in lissencephalia (smooth brain) or other lesions, such as agenesis of the corpus callosum. Abnormalities in intrauterine cerebral blood flow, if severe, can result in the rare disorder of hydranencephaly and, if less severe, porencephaly characterized by cystic spaces in the brain parenchyma.

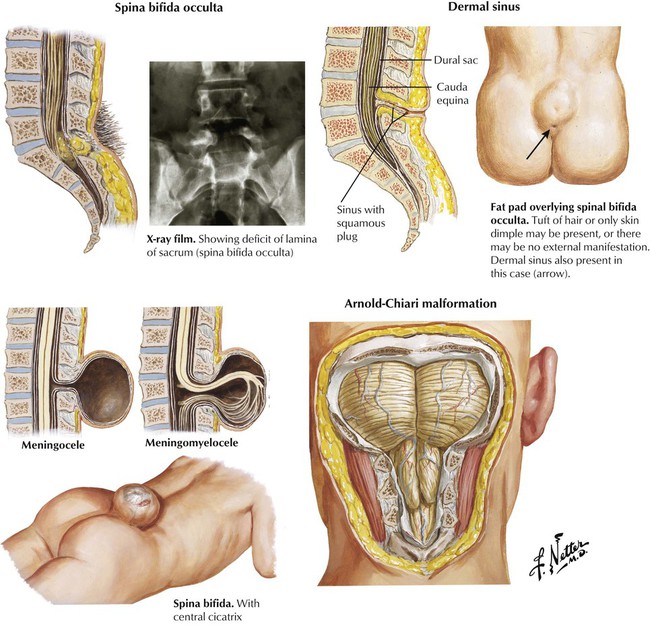

Spinal dysraphism includes several conditions characterized by congenital failure of fusion of the midline structures of the spinal column. The resultant clinical spectrum ranges from an asymptomatic bony abnormality (spina bifida occulta) to severe and disabling malformation of the spinal column and spinal cord (meningomyelocele). Lesions in the lumbosacral region and higher may produce paraplegia and loss of bowel and bladder control; hydrocephalus develops in approximately 90% of cases. The hydrocephalus is related to a congenital deformity of the hindbrain, known as the Arnold-Chiari malformation, in which the posterior fossa structures are downwardly displaced into the spinal canal and interfere with the circulation and absorption of CSF.

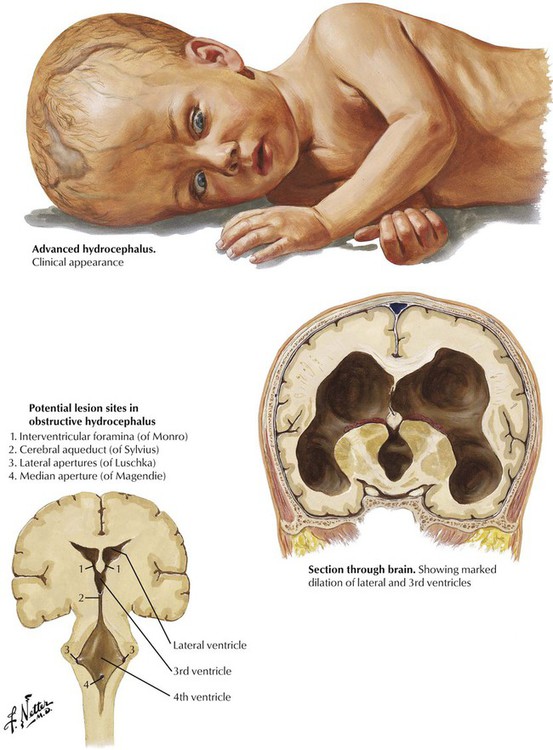

Hydrocephalus, characterized by enlargement of the ventricles of the brain, results from increased formation or decreased absorption of CSF (communicating hydrocephalus) or from blockage of one of the normal outflow paths of the ventricular system (obstructive hydrocephalus). Obstructive hydrocephalus often results from a congenital stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius, but a brainstem tumor or a posterior fossa tumor encroaching on the fourth ventricle that obstructs one of the medial or lateral apertures can produce the same effect. In adults, brain tumors are the usual cause of obstructive hydrocephalus. Communicating hydrocephalus may occur in premature infants after intraventricular hemorrhage. In children and adults, communicating hydrocephalus with increased intracranial pressure may follow an intracranial hemorrhage or infection. Adults also may have normal-pressure hydrocephalus, which must be differentiated from ventricular dilatation secondary to brain atrophy (hydrocephalus ex vacuo).

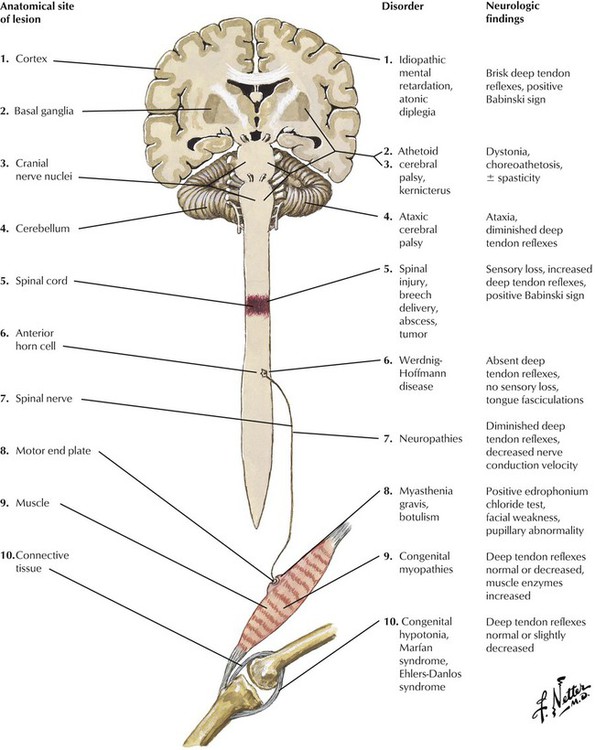

Hypotonia is an important clinical sign of neurologic problems in infants and young children. Classically, the infant hangs like a rag doll when lifted under the abdomen and exhibits weakness and flaccidity of all muscles. Muscle weakness coexisting with hypotonia indicates involvement of the peripheral nervous system, whereas the presence of brisk reflexes and a positive Babinski sign indicate involvement of the central nervous system. Friedreich ataxia, which is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, is the most common of the spinocerebellar degenerations in older children. The differential diagnosis includes various congenital myopathies and connective tissue diseases. Neurologic disease in infants and young children can also result from several inherited single gene defects of lipid metabolism (Niemann-Pick disease, Gaucher disease, and metachromatic leukodystrophy).

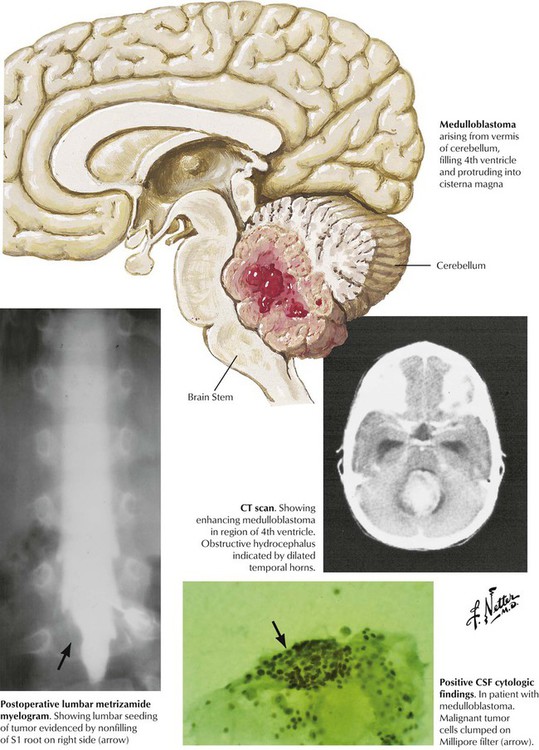

Brain tumors in children are found most commonly in the posterior fossa. The more common astrocytomas and medulloblastomas develop from the parenchyma of the cerebellum. Symptoms include evidence of cerebellar dysfunction (ataxia of the trunk and extremities) and obstruction of CSF flow, leading to headache, nausea, and vomiting. Other tumors include ependymomas, which originate from the ependymal cells lining the ventricular system, and brainstem gliomas. Treatment of posterior fossa tumors involving a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, can yield a favorable prognosis, whereas the prognosis for brainstem gliomas is generally poor.

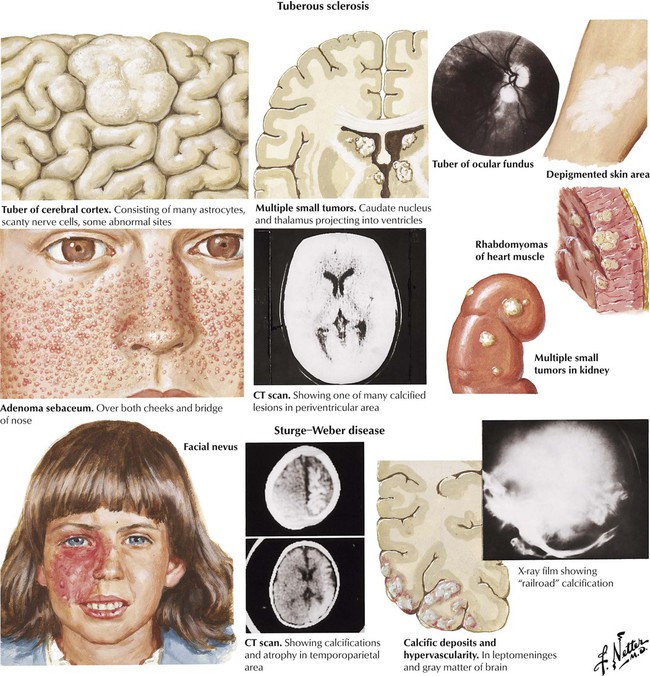

Tuberous sclerosis is a neurocutaneous syndrome caused by a genetic mutation that occurs spontaneously or is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Tubers, foci of abnormal neural tissue growth, form in the nervous system and the retina. The clinical features in childhood are dominated by epilepsy and mental retardation, although some patients may have neither manifestation. Cutaneous manifestations include adenoma sebaceum, depigmented nevi, a shagreen patch in the lumbar area, and subungual fibromas. Some patients have cardiac tumors, known as rhabdomyomas, or angiomyolipomas in the kidneys or both. Sturge-Weber disease, which occurs sporadically, presents with a characteristic port-wine nevus that is apparent at birth. Brain lesions consist of hypervascularity and calcification in the leptomeninges and gray matter. The course is progressive, with increasing seizures and hemiparesis.

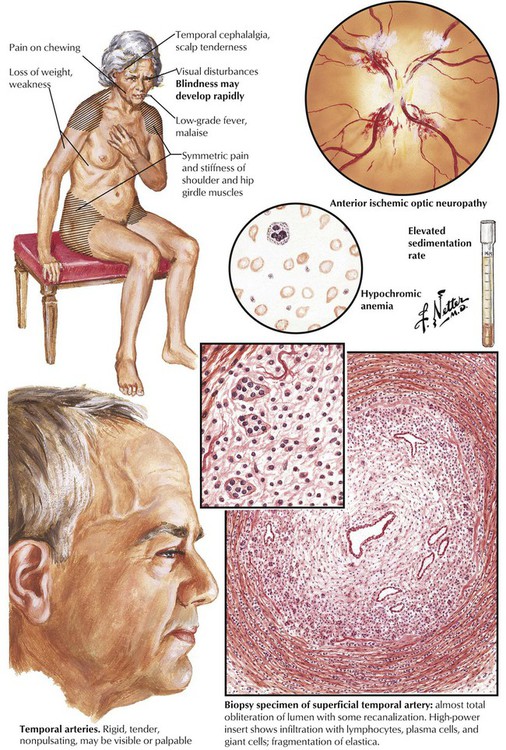

The headache syndromes include migraine (vascular headache), cluster headache (a migraine variant), muscle contraction headache (often stress related), and headache due to temporal (giant cell) arteritis. Temporal (giant cell) arteritis is an inflammatory disease that occurs in older individuals and affects the temporal branches of the external carotid artery. A steady, aching pain in the temporal and occipital regions, often accompanied by malaise and fever, is symptomatic. The temporal and occipital arteries are firm, tender, and pulseless. Histologically, the arteries are infiltrated by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and giant cells, and the lumen is occluded by organized thrombus. Intracranial vessels are affected occasionally, and blindness can result when ophthalmic arteries are involved. The generalized malaise, muscle pain and stiffness, fever, and other symptoms constitute an associated syndrome of polymyalgia rheumatica.

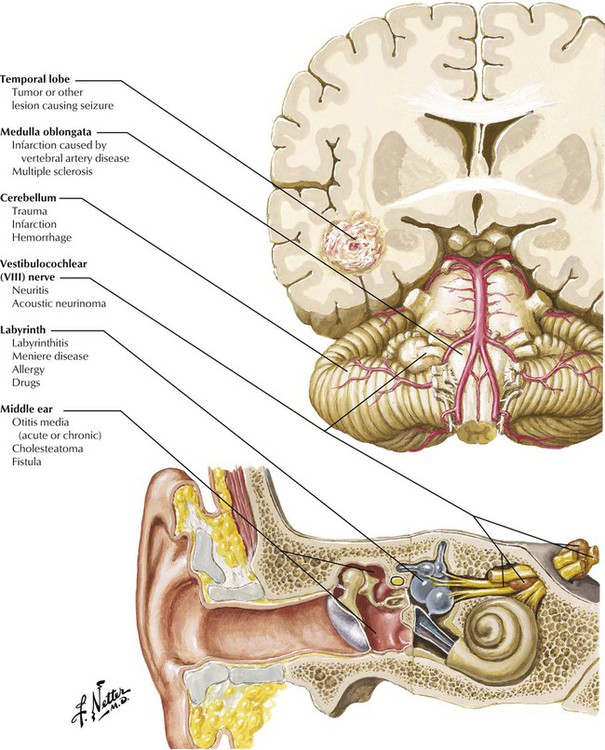

Dizziness is a general term used to describe a variety of feelings related to a disturbed sense of relation to space, including unsteadiness and giddiness. Vertigo refers more specifically to a sensation of exterior motion, often described as spinning, turning, or rotating of the external environment in relation to the person. Vertigo may be caused by dysfunction of any of the structures that are involved in sound detection or the relay of signals from the vestibular apparatus of the ear to the brain. Useful clues to localization include an analysis of effect of movement or change in position, features of the motion, abnormal symptoms or signs related to dysfunction of adjacent structures, previous attacks, nystagmus, and laboratory tests such as electroencephalography, audiometric tests, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

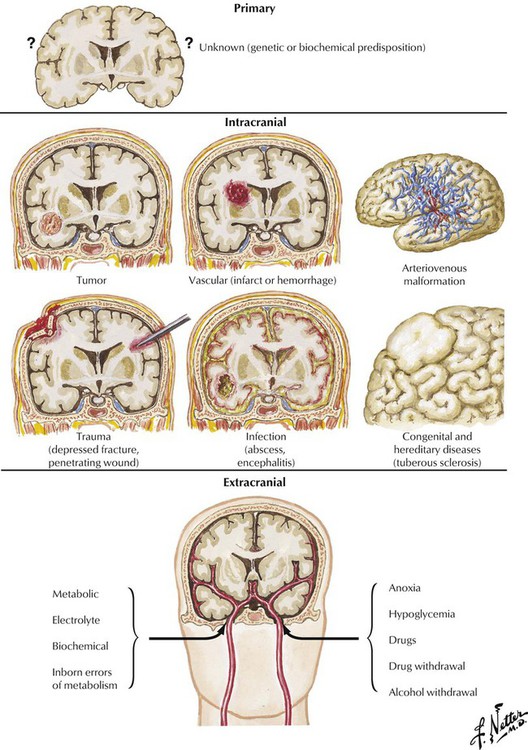

Seizures are triggered by the sudden and intense increase in the discharge of neurons and constitute the symptomatic expression of epilepsy. Primary seizures are of unknown etiology and are typically generalized without (petit mal) or with tonic-clonic muscle contractions (grand mal). Secondary seizures, which may be focal or generalized, result from an identifiable pathologic lesion or disease process, which may be either intracranial or extracranial. The most common intracranial lesions causing seizures are tumors, vascular lesions, head trauma, infectious diseases, congenital defects, and biochemical or degenerative diseases affecting the brain. Extracranial causes of seizures include various metabolic, electrolyte, and biochemical disturbances; fever; inborn errors of metabolism; anoxia; hypoglycemia; toxic processes; and drugs or abrupt withdrawal from drugs or alcohol.

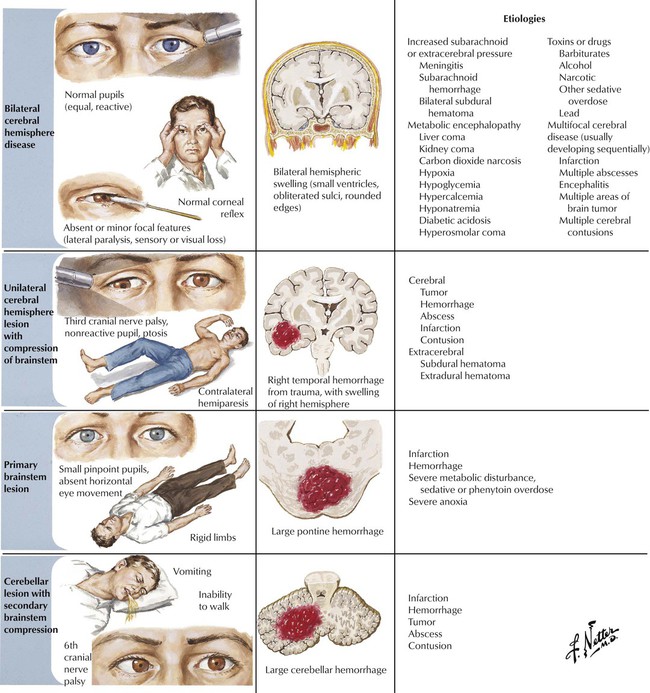

Coma results from loss of consciousness as indicated by the complete absence of awareness of the environment or response to environmental stimuli. Confusion and stupor represent lesser degrees of impairment of consciousness. Consciousness is maintained by coordinated neural activity in both cerebral hemispheres reinforced by the reticular activating system located in the tegmentum of the brainstem. Consciousness is diminished or lost by major impairment of the reticular activating system or extensive damage to both cerebral hemispheres. The basic pathophysiologic mechanisms for loss of consciousness are (1) bilateral cerebral hemisphere disease, (2) unilateral cerebral hemisphere lesion with compression of the brainstem, (3) primary brainstem lesion, and (4) cerebellar lesion with secondary brainstem compression. These should be differentiated from nonorganic or feigned stupor.

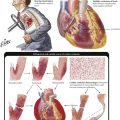

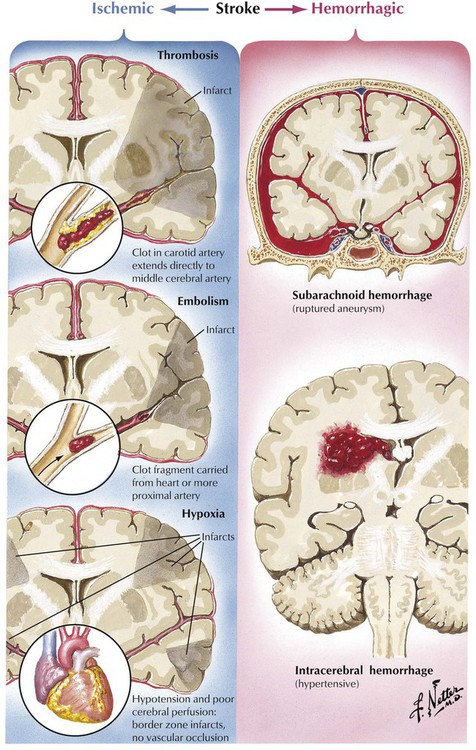

Stroke refers to a constellation of disorders in which brain injury is caused by a vascular disorder. The 2 major categories of stroke are ischemic, in which inadequate blood flow due to thrombosis, embolism, or generalized hypoxia causes one or more localized areas of cerebral infarction, and hemorrhagic, in which bleeding in the brain parenchyma or subarachnoid space causes damage and displacement of brain structures. The clinical spectrum of focal cerebral ischemic events includes transient ischemic attacks, residual ischemic neurologic deficit, and completed infarction.

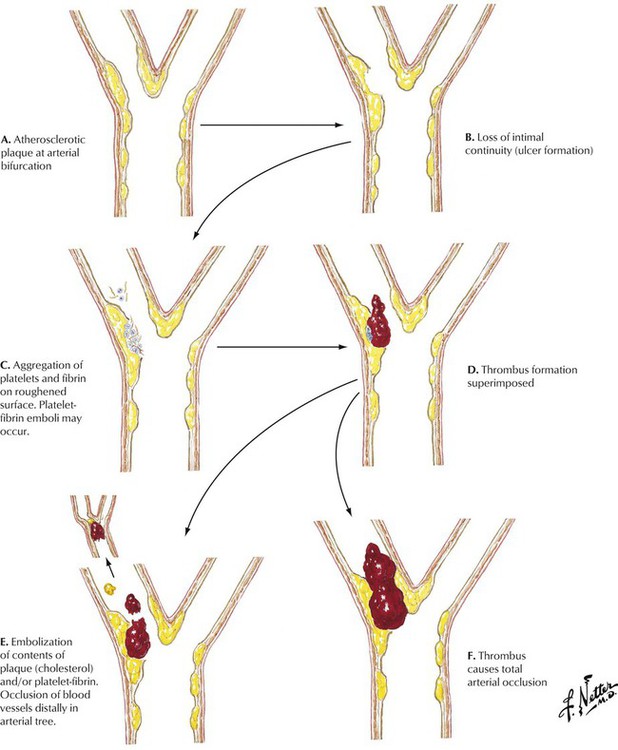

Atherosclerosis is characterized by the development of foci of intimal thickening composed of variable combinations of fibrous and fatty material and known as fibrous (atheromatous) plaques. Such lesions tend to form adjacent to branch points in arteries. The fibrous plaques may remain static, regress, progress, become calcified, or develop into complicated atheromatous lesions called dangerous or vulnerable plaques because they are responsible for clinical disease. Complications include loss of endothelial integrity, overt surface ulceration, aggregation of platelets and fibrin on the eroded plaque surface, hemorrhage in the plaque, formation of mural thrombi, embolization of plaque contents or thrombotic material or both, and total arterial occlusion by thrombus. The consequences of thrombotic occlusion are variable and unpredictable depending on the extent of disease and the amount of preexisting collateral blood flow. Thrombotic occlusion often results in tissue infarction.

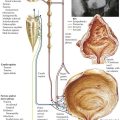

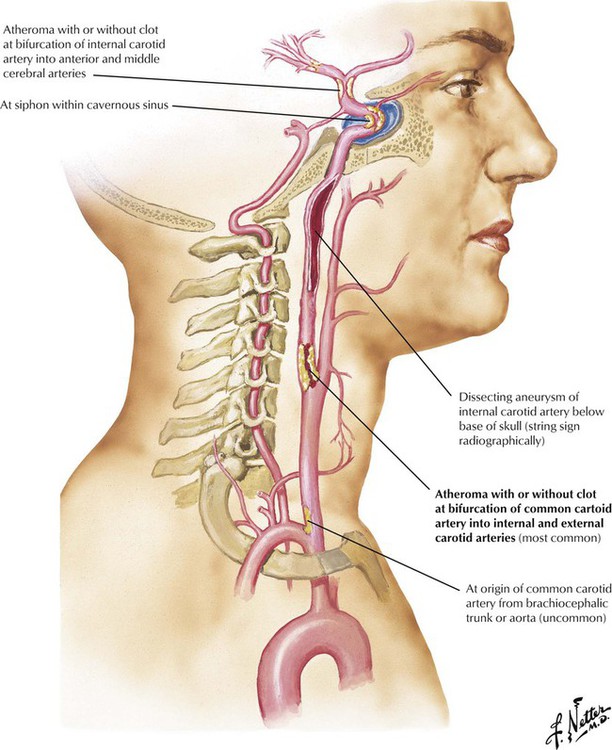

Stenosis or occlusion of a carotid artery accounts for a high percentage of strokes. The most common location for atherosclerosis in the carotid system is at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery into the internal and external carotid arteries. Atherosclerotic stenosis at the origin of the common carotid artery is rare, but aortic arch arteritis (Takayasu disease) can occlude the proximal common carotid artery and other aortic branches. The extracranial pharyngeal portion of the internal carotid artery is usually spared of atherosclerosis but is subject to fibromuscular dysplasia and medial dissection. Atherosclerosis can affect the siphon portion of the carotid artery and the site of bifurcation of the internal carotid artery into anterior and middle cerebral arteries after it has begun its intracranial course. Ischemia in the internal carotid territory can lead to visual field defects, language defects, and hemiparesis or hemiplegia.

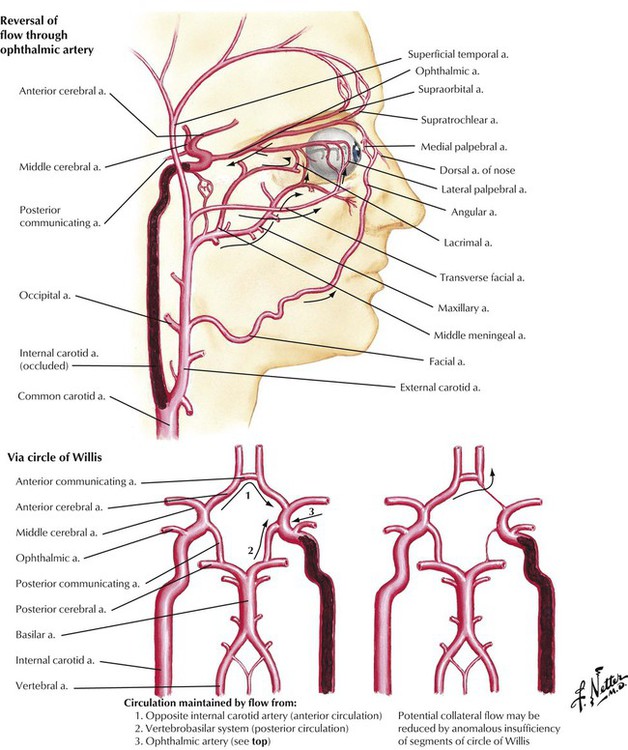

Collateral circulation occurs by blood flow from the vasculature supplied by one major blood vessel into the vascular branches of another major blood vessel through small vascular channels that connect the two systems. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery can be partially ameliorated through collateral circulation. The major extracranial pathways of collateral circulation are anastomoses between the ophthalmic artery and branches of both external carotid arteries. The major intracranial pathways of collateral circulation are the anastomoses formed by the circle of Willis at the base of the brain. The amount of collateral circulation is determined by the specific anatomy of the vascular connections and the extent and distribution of vascular disease.

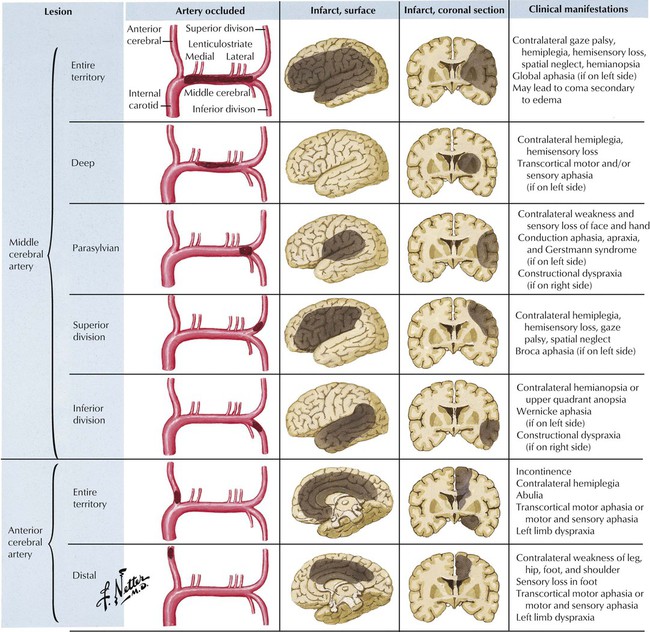

The internal carotid artery bifurcates within the cranial cavity into the anterior cerebral artery (which supplies the anterior paramedian cerebral hemisphere) and the larger middle cerebral artery (which supplies the lateral cerebral hemisphere and most of the basal ganglia) after giving origin to the ophthalmic, anterior choroidal, and posterior communicating artery branches. The middle cerebral artery contributes penetrating lenticulostriate branches that arise from its horizontal main stem and trifurcates near the lateral cerebral (sylvian) fissure into major superior and inferior trunks and a small anterior temporal artery. Occlusion of the main stem of the middle or anterior cerebral artery or their superficial branches is usually caused by an embolus from the heart or the proximal vessels, particularly the internal carotid artery.

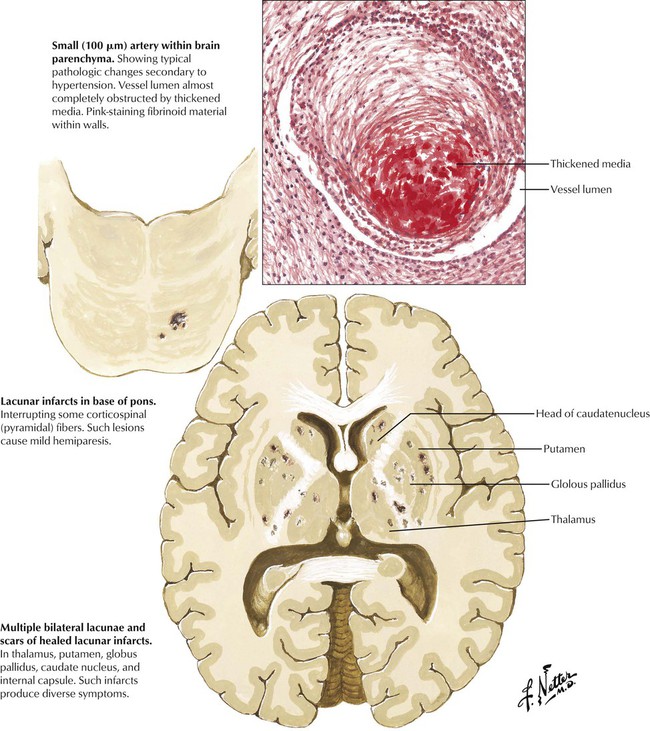

Atherosclerosis involves large- and medium-sized cerebral arteries, whereas hypertension produces disease of small penetrating arteries of the brain. Progressive arteriolosclerosis develops in the small vessels. Hyaline and fibrinoid material thickens the wall and obliterates the lumen. The lacunae (holes), the small, round lesions deep in the brain parenchyma, are commonly found in the brain at autopsy. Some lesions are clinically significant. A small infarct in the base of the pons or internal capsule can produce a pure motor hemiplegia with contralateral weakness of the face, the arm, and the leg but no sensory, visual, or intellectual defects. Other lesions can produce pure sensory strokes. Lacunar lesions in the pons can produce several syndromes, including hemiparesis coupled with ataxia.

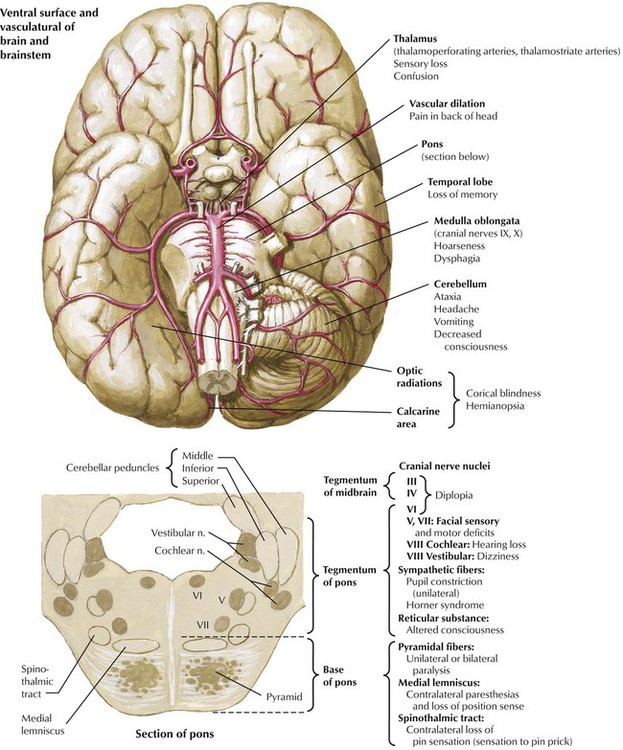

Ischemia in the vertebrobasilar territory accounts for approximately a fifth of all cerebrovascular accidents. Ischemia in the vertebrobasilar system may produce impairment of the brainstem, the cerebellar hemispheres, or the occipital lobes of the cerebral hemispheres. Symptoms and signs include altered consciousness, ataxia, vertigo, motor and sensory deficits of the extremities, visual field defects, and palsy of one or more of the cranial nerves. This illustration shows the relation between areas of the brain affected by various sites of vascular pathology and the associated neurologic symptoms. Atherosclerosis of the basilar artery and posterior cerebral arteries is a common cause of strokes in this region. Also, atherosclerosis and pulseless disease (Takayasu arteritis) may involve the subclavian artery and its right or left vertebral artery branches. Ischemia also can result from trauma of the third segment of the vertebral artery as it enters the posterior fossa.

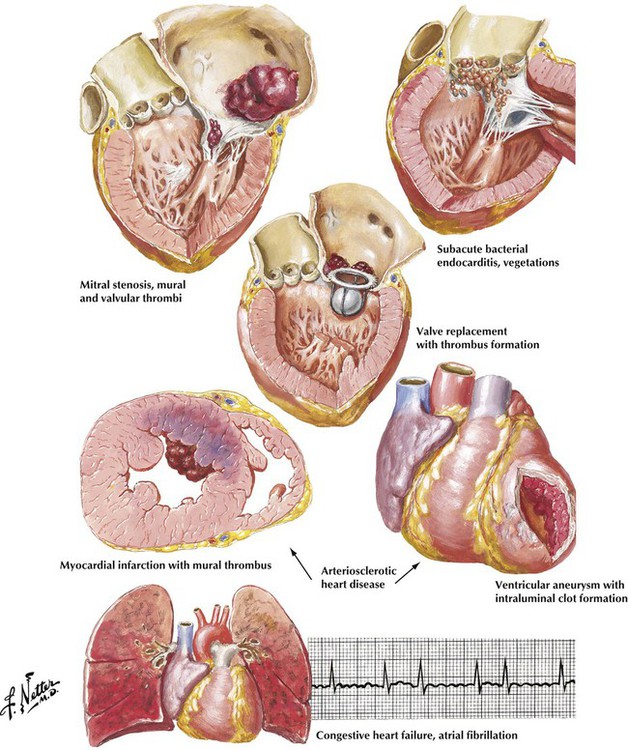

The classic presentation of a stroke of embolic cause is the abrupt loss of neurologic function confined to the distribution of a major cerebral vessel or one of its major branches without previous transient ischemic episodes. In various studies, findings suggestive of an embolic origin have been identified in as many as 50% of patients presenting with stroke. The major sites of origin of cerebral emboli are carotid artery atheromas and a variety of cardiac lesions. Atrial fibrillation is an important pathophysiologic alteration that can give rise to intracardiac thrombus formation and subsequent cerebral emboli. Atrial fibrillation develops most often in patients with arteriosclerotic heart disease and congestive heart failure of various causes. Emboli also can arise from thrombi forming on prosthetic valves, from vegetations of bacterial endocarditis, and from mural thrombi at sites of acute myocardial infarction or ventricular aneurysms.

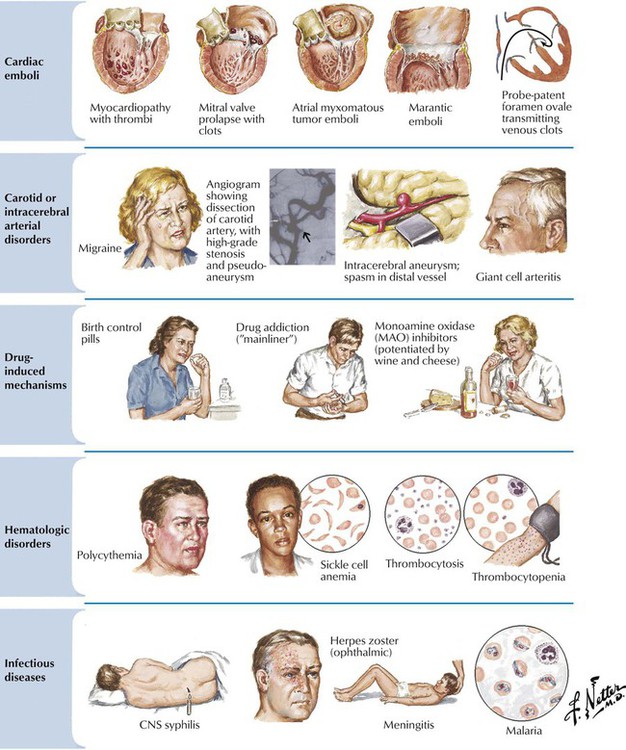

Less common but treatable mechanisms should be considered before concluding that stroke is due to cerebral atherosclerosis, including cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, atrial myxoma, marantic vegetations (nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis), and paradoxical emboli across a probe-patent foramen ovale. Echocardiography and angiography are important diagnostic procedures to detect cardiac or unusual carotid or intracerebral arterial disorders. Also included in the differential diagnosis are conditions that may be associated with markers of inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein), such as intracranial temporal arteritis, other vasculitides, bacterial endocarditis, or atrial myxoma. Abnormal cerebrovascular fluid examination results may lead to a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis or other forms of nervous system infection. Abnormalities affecting platelets or red blood cells may contribute to stroke, and consideration should be given to drug-induced mechanisms of stroke.

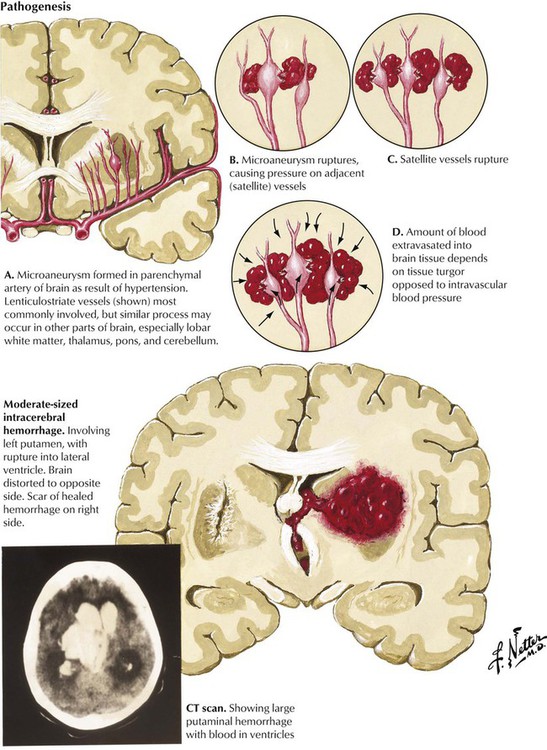

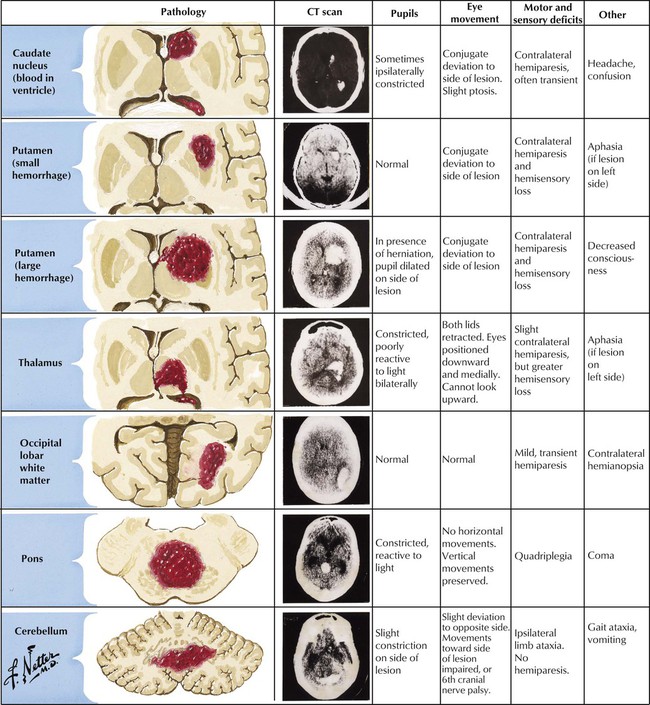

Hypertension is the most common and important etiologic factor in intracerebral hemorrhage. Over time, degenerative changes of the small arteries lead to the formation of microaneurysms. The penetrating lenticulostriate branches of the middle cerebral artery are most commonly involved, but similar changes can occur in small vessels in other parts of the brain. Hemorrhages tend to dissect through white matter pathways, thereby disrupting the cerebral cortex. The enlarging hematoma may extend onto the cerebral surface, producing subarachnoid hemorrhage or rupture into the ventricles. Hypertensive hemorrhage typically occurs in regions where small lacunar lesions develop (see Fig. 13-17) and involve, in descending order of frequency, the putamen, the cerebral white matter, the thalamus, pons, the cerebellum, and the caudate nucleus. Hemorrhages usually begin while the patient is awake and engaged in daily activity. As the hematoma expands, the focal neurologic deficit gradually increases during a period of minutes or a few hours.

Symptoms and specific signs of neurologic deficit relate to the site and size of the intracerebral hemorrhage. Hypertension-induced damage of small arteries is the most common cause of intracerebral hemorrhage. Other causes include arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), bleeding diatheses (natural disease or anticoagulant induced), trauma, drug abuse (amphetamines or cocaine), and amyloid angiopathy (a degenerative vasculopathy seen in elderly patients). CT and MRI confirm the diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage. The hemorrhages appear as round, well-circumscribed lesions of uniform high density on CT scans. Large hemorrhages are often fatal. Small hemorrhages can resolve if blood pressure is controlled. Surgical drainage of medium-sized hemorrhages can occasionally be lifesaving.

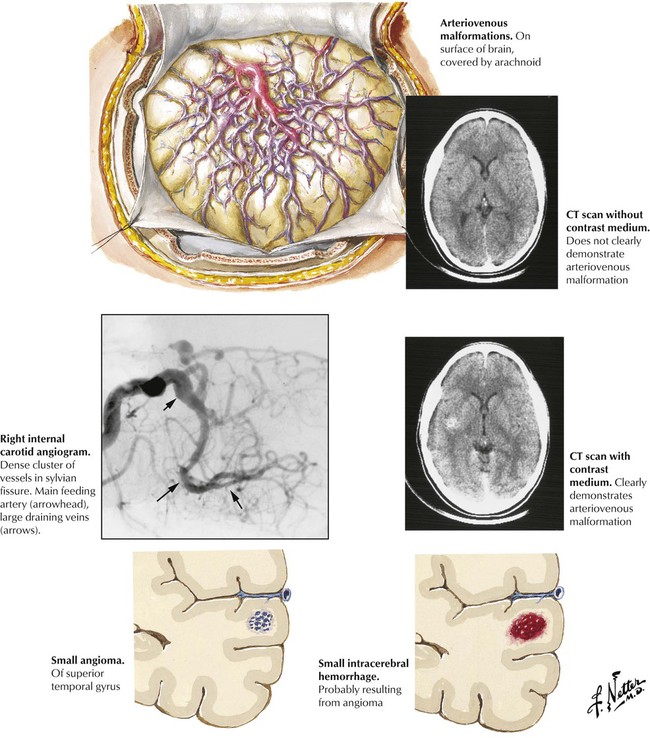

Vascular malformations are congenital anomalies that can cause intracerebral or subarachnoid hemorrhage. There are 4 categories: (1) AVMs characterized by direct connections between arteries and veins, with the veins becoming arterialized by exposure to high pressure; (2) capillary angiomas, or telangiectases, consisting of malformations of arterioles and capillaries; (3) cavernous angiomas, consisting of dilated abnormal vessels of various sizes, with no intervening neural tissue; and (4) venous angiomas, consisting of large aggregates of veins (caput medusae). Complications include headache, epileptic seizures, and bleeding. Treatment may involve surgical ablation or ablation by various interventional neuroradiologic procedures.

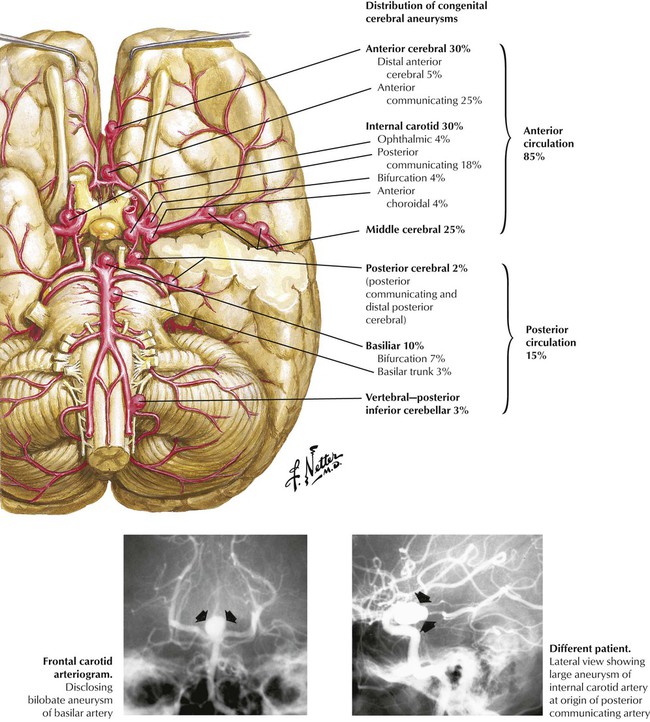

Although saccular (berry) aneurysms are generally referred to as congenital aneurysms, they are actually caused by a combination of congenital and acquired factors. The congenital defect is a focal absence of the media, particularly at arterial bifurcations. Hemodynamic forces cause the intima to bulge into the adventitia creating the aneurysm, followed by intimal proliferation. Atherosclerosis and hypertension accelerate the process. The relative distribution of aneurysms involving arteries of the circle of Willis and distributing branches is illustrated. Complications of a rupture include subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, infarction, and vasospasm. The onset of symptoms after aneurysm rupture is abrupt and rapid, with sudden, severe headache and alteration in consciousness. The mortality rate from rupture is high; rapid diagnosis and surgical intervention are essential to prevent death.

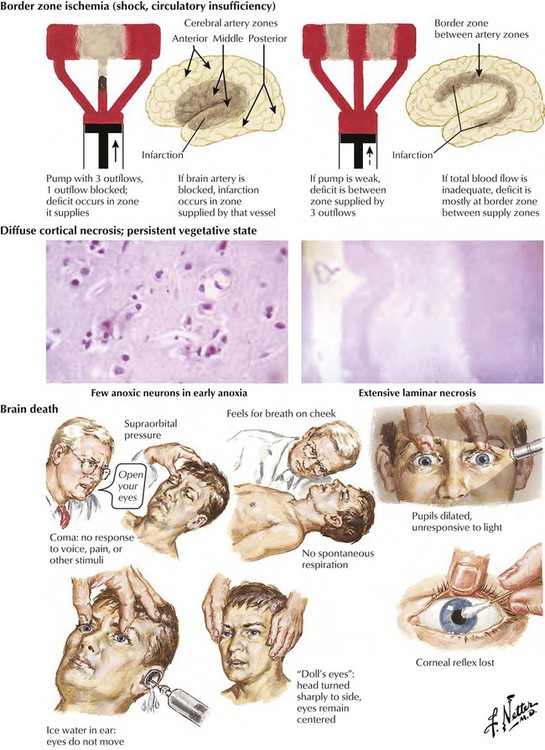

Cardiac arrest or severe cardiac failure leads rapidly to generalized hypoperfusion of the brain and hypoxic brain injury. The extent, severity, and location of hypoxic brain damage are influenced by the degree and duration of circulation collapse (full cardiac arrest or hypotension, with some preserved cardiac pump function) and other factors, such as accompanying respiratory failure. Persistent hypotension usually leads to border zone ischemic lesions, whereas cardiac arrest causes more extensive cortical necrosis, which may include the cerebral gray matter, brainstem nuclei, and the hippocampus. Regions of the brain most susceptible to ischemic damage are the Purkinje cells of the cerebellum, the hippocampus, and border zone (watershed) regions at the boundaries of the territories of major arteries supplying the cerebral cortex. Severe ischemia sets in motion a chain of events leading to irreversible brain death.

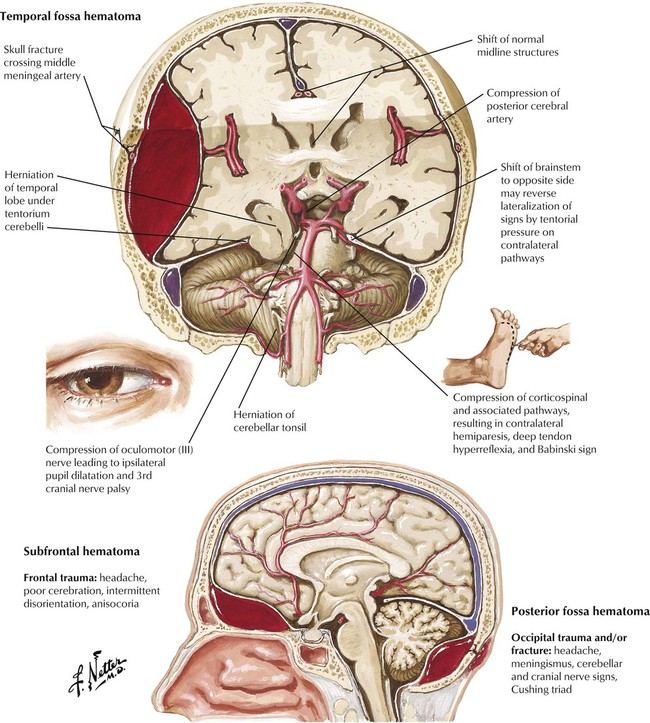

Traumatic brain injuries include concussion, contusion, skull fracture, and, in a small percentage of major head injuries, epidural hematomas. Usually, the bleeding is from arterial injury. Common locations of epidural hematomas are the temporal fossa, the subfrontal region, and the occipital-suboccipital area. The temporal fossa epidural hematoma, which results from damage to the middle meningeal artery, is the most common epidural hematoma. The classic course is a period of unconsciousness due to a concussion, a period of lucidity as the dura mater initially slows the leakage of blood, and a rapid deterioration of consciousness. An aggressive diagnostic and surgical approach is required to save the patient.

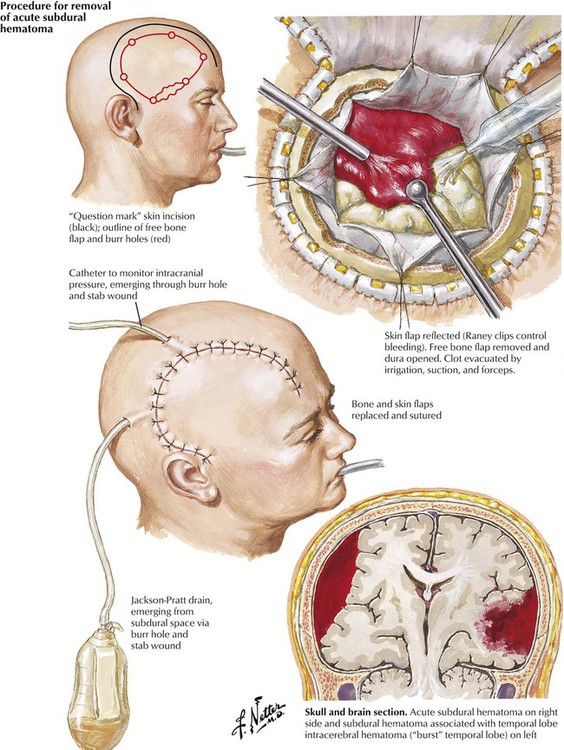

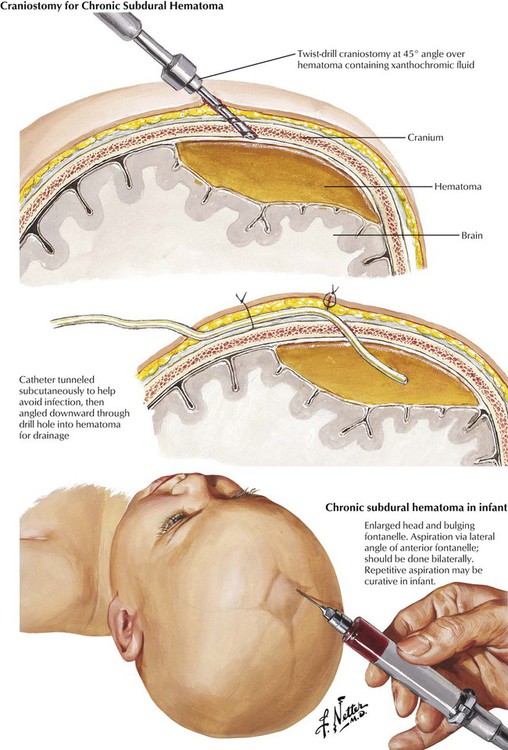

A subdural hematoma usually results from an acute venous hemorrhage caused by rupture of cortical bridging veins. Acute subdural hematomas, which are often associated with skull fractures, usually develop within hours after injury. Associated massive cerebral or brainstem contusions or both contribute to a high mortality rate. Common signs are depressed consciousness, ipsilateral pupillary dilatation, and contralateral hemiparesis. Chronic subdural hematomas in infants can occur as a result of birth trauma. In adults, they are more common in the elderly, patients with chronic alcoholism, and patients receiving long-term anticoagulant therapy or who have a blood dyscrasia. The precipitating trauma is often trivial. Brain atrophy with an increase in the subdural space is a predisposing factor. A vascular membrane forms around the lesion within 2 weeks after the initial hemorrhage fills the available subdural space. The hematoma enlarges slowly until it produces symptoms. The clinical course can be subtle, with waxing and waning signs and symptoms. The differential diagnosis includes stroke, infection, or psychosis.

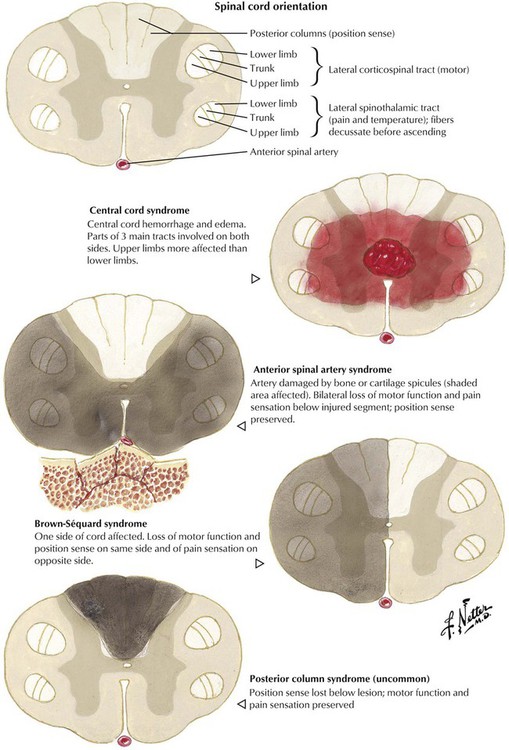

Spinal cord injuries are produced by motor vehicle accidents, other types of accidents, and missile or knife wounds. Spinal cord injury, which involves direct neuronal trauma and direct and delayed injury to the vasculature, can result in a variety of neurologic deficits. The most frequent injuries occur at the levels of the lower cervical vertebrae and the thoracolumbar junction. The resulting neurologic deficits comprise complete functional interruption, partial functional interruption, nerve root deficit, Brown-Séquard syndrome, central cord damage, and other deficits. Initial treatment is aimed at reducing the extent of damage by preventing the delayed component of injury. Currently, there is great expectation that neuronal regeneration can be achieved to treat patients with paraplegia and other deficits from spinal cord injury.

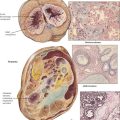

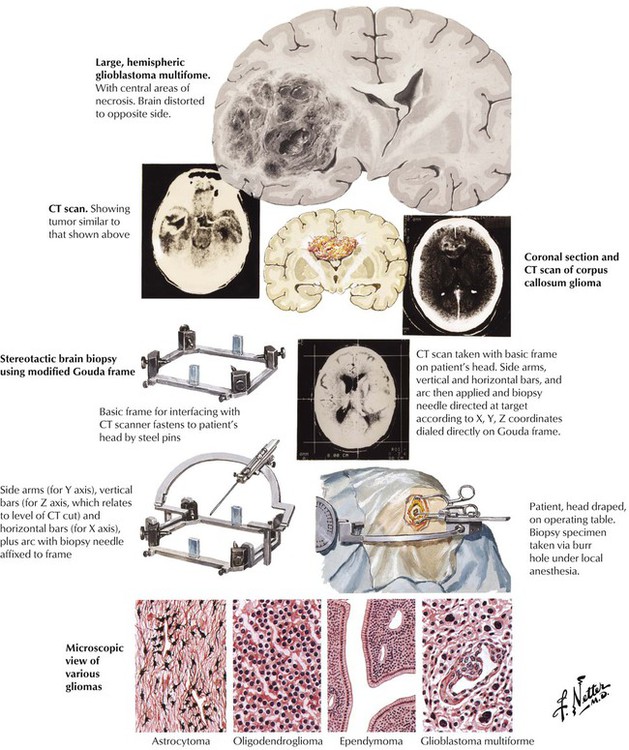

Patients with brain tumors present with symptoms resulting from either increased intracranial pressure or focal brain dysfunction. Gliomas, the most common tumors of the brain, arise from the glial supporting tissue rather than the neurons. The tumors show differentiation toward any of the normal glial components (astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, ependymoma, and ganglioneuroma). The tumors of each cell type range from moderately well-differentiated, slow-growing neoplasms to pleomorphic, rapidly growing tumors, the most common of which is the glioblastoma multiforme. The glioblastomas are characterized by vascular proliferation and necrosis and cellular pleomorphism. The prognosis, which varies with the location and type of tumor, is difficult to determine because glioblastomas may show a mixed pattern with high-grade areas adjacent to low-grade areas, and low-grade tumors tend to progress over time to high-grade lesions.

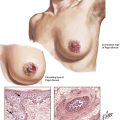

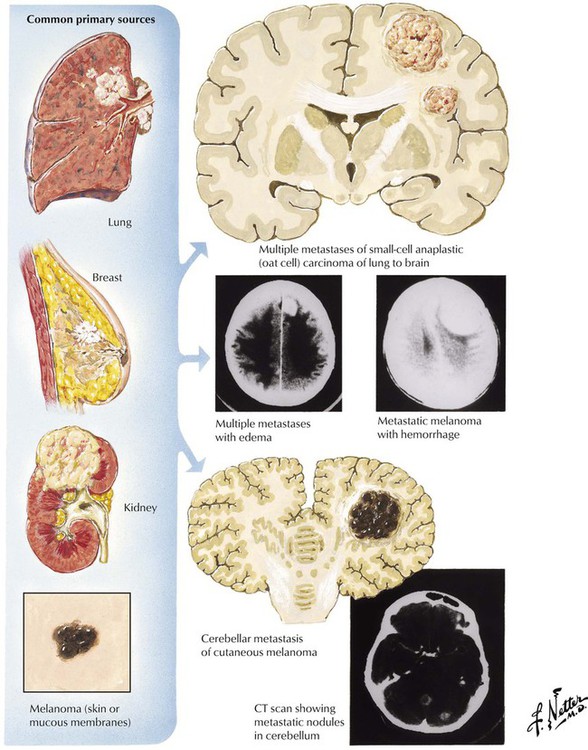

Certain common neoplasms, particularly carcinomas of the lung and the breast, as well as less common neoplasms, including carcinoma of the kidney and melanoma, have a propensity to metastasize to the brain or spinal cord. Metastatic brain tumors are more common than primary brain tumors. Brain metastases may be the first manifestation of an aggressive tumor such as lung cancer. Most metastatic tumors reach the brain through the bloodstream (hematogenous metastases) and become localized at the border between white and gray matter, although occasionally a tumor may spread directly to the brain by local extension from a head and neck cancer or via Batson venous plexus. Metastatic tumors are usually well demarcated and solid, but they may be cystic. Some tumors may be hemorrhagic at the time of presentation, confusing the real diagnosis. The lesions are frequently multiple. CSF examination may yield evidence of meningeal carcinomatosis.

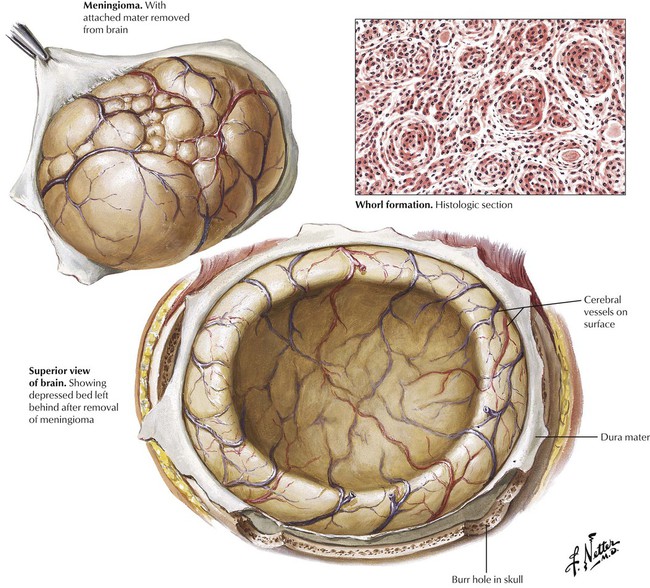

Meningiomas are the most common of the benign brain tumors. Their incidence increases with age, with a moderate female preponderance. Meningiomas, which arise from arachnoid cells in the meninges, are nearly always benign, but rare malignant variants occur. Most meningiomas are composed of groups of cells arranged in a whorled pattern without identifiable cell membranes (syncytial type), sometimes containing large numbers of calcified psammoma bodies (psammomatous type). Fibroblastic and transitional variants also occur. The symptoms depend on location of the tumor, the growth rate, and adherence to adjacent structures rather than on histologic type. Meningiomas may extend into venous structures, such as the superior sagittal sinus, or erode into the bone of the skull.

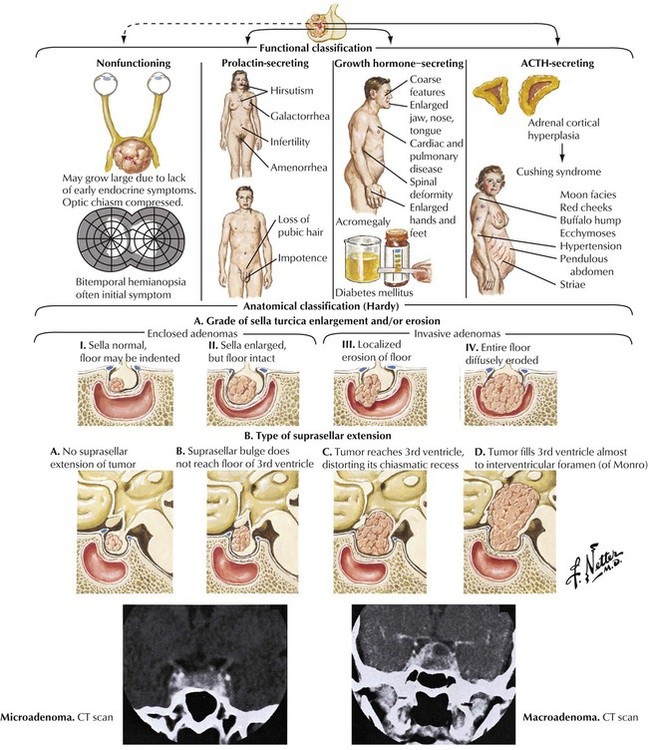

Pituitary tumors of the adenohypophysis are classified on both a functional and an anatomical basis. With the use of standard histology, the tumors are classified as eosinophilic adenoma, basophilic adenoma, and chromophobe adenoma. The eosinophilic adenoma is associated with acromegaly, and the basophilic adenoma is associated with Cushing syndrome. The chromophobe adenoma, the most common type of tumor, may be nonfunctioning. A more accurate classification can be obtained by immunocytochemical staining for specific hormones. Clinically important features include the degree of sella turcica enlargement and erosion and the type of suprasellar extension. Precise delineation of tumor extent can be obtained with a combination of CT and MRI scans and angiography.

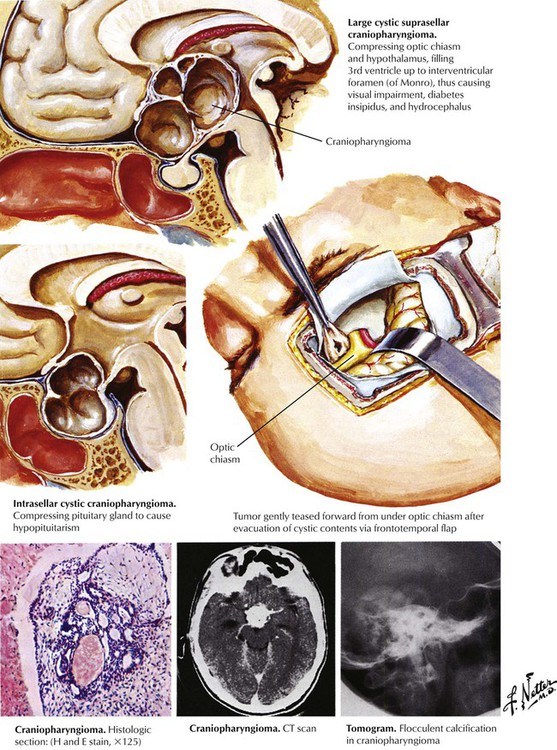

Craniopharyngiomas are the most common parasellar tumors in children, but they also occur in adults. Craniopharyngiomas arise from remnants of the Rathke pouch derived from the embryonic pharynx. The lesion is composed of clusters of columnar and cuboidal epithelial cells. The tumor may be solid or cystic because of formation of degenerative areas containing oily fluid, calcium, and keratin. The tumor routinely extends to the optic chiasm. A craniopharyngioma produces visual symptoms secondary to compression of the optic tract. Approximately 50% of patients have endocrine dysfunction, with diabetes insipidus, panhypopituitarism, and gonadal deficiency in adults and growth retardation and obesity in children. Hydrocephalus, often with papilledema, also can develop in children with this tumor.

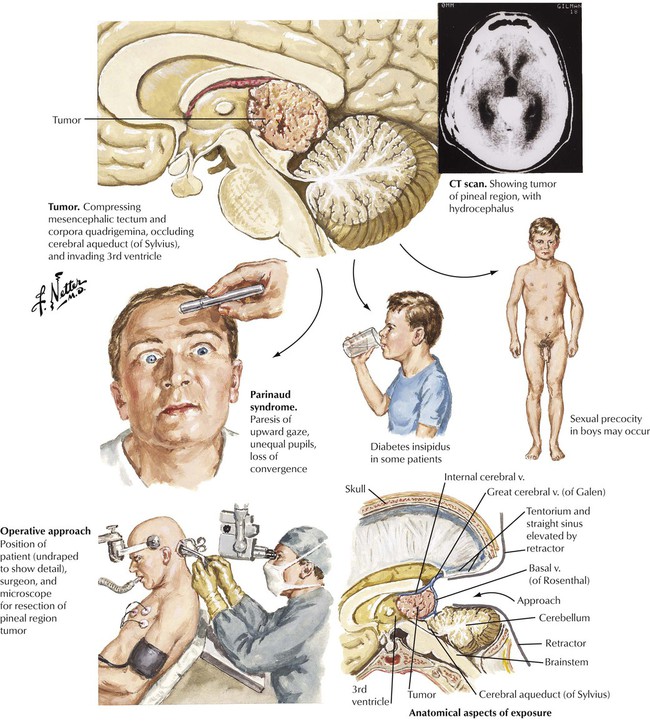

The pineal gland has a strategic central location in the brain surrounded by vital structures, including the posterior third ventricle. Symptoms result from compression or involvement of these vital structures by the pineal tumor. Pineal tumors can be classified into tumors of germ cell origin, tumors of the pineal parenchyma, and a miscellaneous group. Tumors of germ cell origin are germinomas and teratomas. Germinomas, which comprise approximately half of all pineal tumors, are most common in adolescents and have a marked predilection for males. Teratomas have a similar male predilection. These tumors usually present with endocrine abnormalities. The germinoma usually spreads via the CSF but is radiosensitive, whereas teratomas are not invasive. Pinealcytoma is well circumscribed and noninvasive. It occurs at any age and has no sex predilection. The malignant pineal blastoma is composed of primitive cells resembling medulloblastoma and spreads within the CSF. Other pineal tumors include benign meningiomas and cysts.

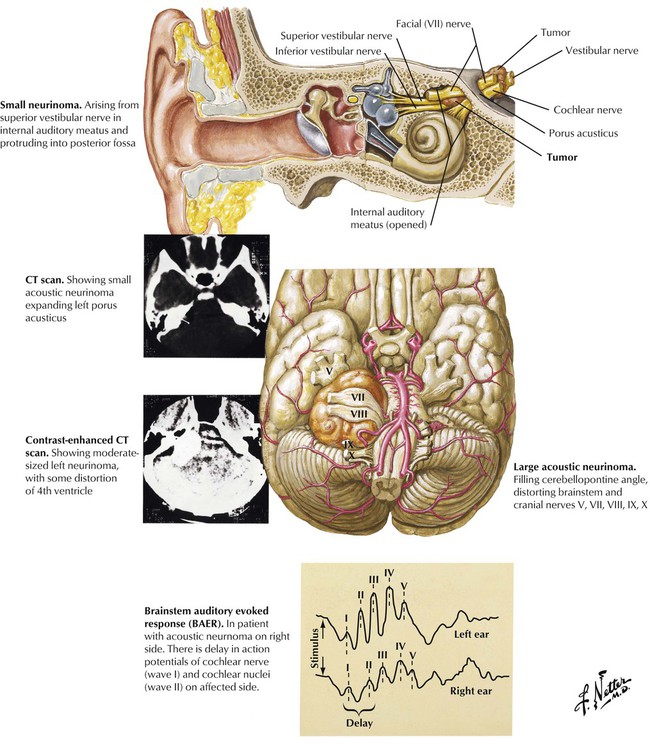

Acoustic neuromas cause characteristic symptoms resulting from a mass effect in the cerebellopontine angle. The acoustic neuroma typically arises from the Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve, and the tumor slowly impairs the vestibular and cochlear nerves. Undiagnosed, the tumor can continue to expand and produce brainstem compression and hydrocephalus. In addition to hearing loss and tinnitus, early symptoms of acoustic neuroma may include tic douloureux, ataxia, facial sensory loss, or, occasionally, even dementia. A hearing loss for high tones, with impaired speech discrimination, frequently occurs. Involvement of the facial (VII) and trigeminal (V) nerves indicates a large tumor.

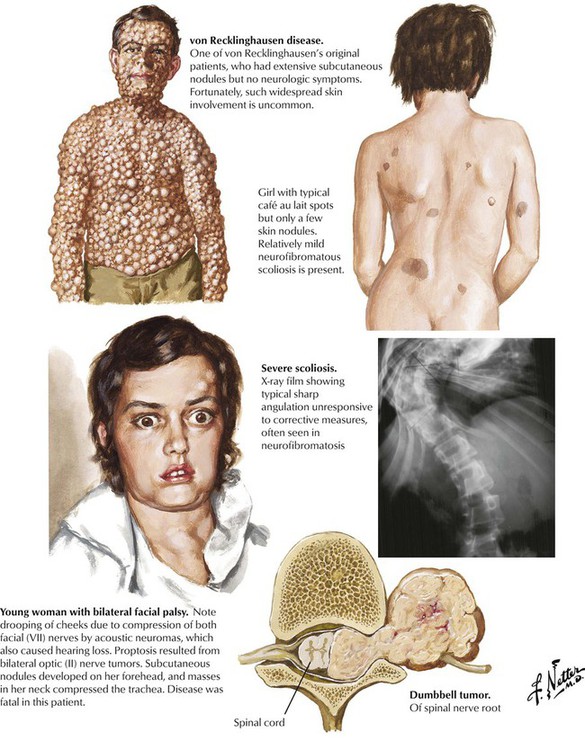

Neurofibromatosis, or von Recklinghausen disease, is the most common of a group of inherited disorders known as phacomatoses that involve tissues derived embryologically from the neural crest, including the nervous system and components of the skin. Pathologic lesions of neurofibromatosis consist of café-au-lait spots representing cutaneous patches formed by melanin-containing cells derived from the neural crest and neurofibromas formed from neural crest–derived Schwann cells involving the cranial and peripheral nerves. Gliomas and meningiomas also occur with increased frequency in neurofibromatosis. Peripheral neurofibromatosis is characterized by multiple subcutaneous tumors of the peripheral nerves but without apparent central nervous system involvement. The various forms of neurofibromatosis represent a common group of human genetic mutations, with autosomal dominant inheritance. Bilateral acoustic neuromas and other intracranial lesions can produce debilitating disease.

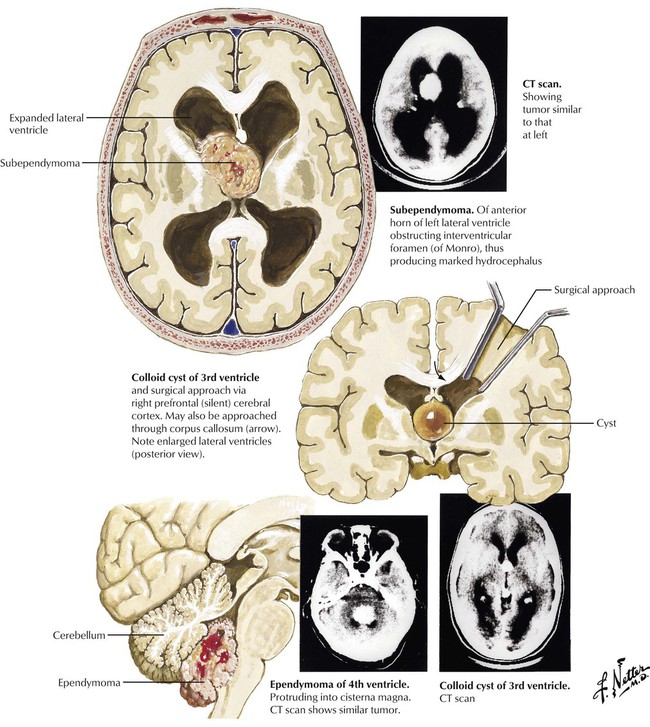

Intraventricular tumors are a heterogeneous group that shares a unique position within the brain. These lesions produce symptoms by local pressure and invasion, with the common finding being hydrocephalus. Tumors of the lateral ventricles may arise from the choroid plexus (meningioma and choroid plexus papilloma) or from the brain parenchyma (ependymoma, astrocytoma, subependymoma, and the giant cell tumor of tuberous sclerosis). Anterior third ventricle tumors are colloid cysts, giant craniopharyngioma, and pituitary adenoma. Posterior third ventricle tumors are pineal gland tumors. Tumors of the posterior cranial fossa can be subdivided into 3 groups. The extracerebral tumors are acoustic neuroma, meningioma, and cholesteatoma. Cerebellar hemispheric tumors are cystic astrocytoma and medulloblastoma in children and metastases and astrocytoma in adults. Tumors of the fourth ventricle are ependymoma and subependymoma.

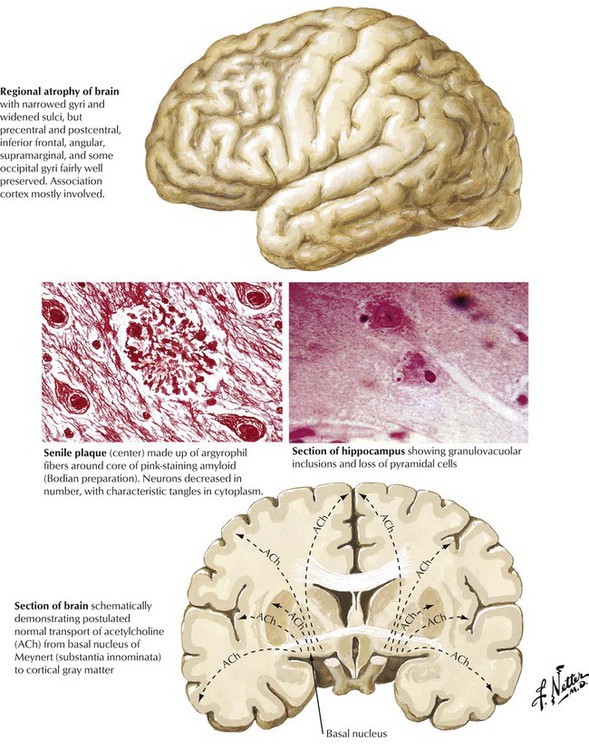

Alzheimer disease, a distinctive form of senile dementia, is a progressive neurologic disorder usually presenting in older adults and characterized by slowly progressive loss of higher intellectual capacity and memory followed by more severe cerebral dysfunction. The distinctive pathologic lesions are the so-called senile plaques, composed of argyrophilic fibers surrounding a central core of amyloid material, and the argyrophilic neurofibrillary tangles in neurons. Granulovacuolar inclusions may also be seen in some neurons. The process results in progressive loss of neurons and cerebral atrophy. The regions of the brain most involved in Alzheimer disease correspond to pathways of neurotransmitter transport, specifically acetylcholine. Certain brain regions, the precentral, postcentral, and some occipital gyri and perisylvian regions, for example, are spared, whereas the prefrontal, superior parietal, and inferior temporal gyri become severely atrophied, eventually involving the frontal lobes.

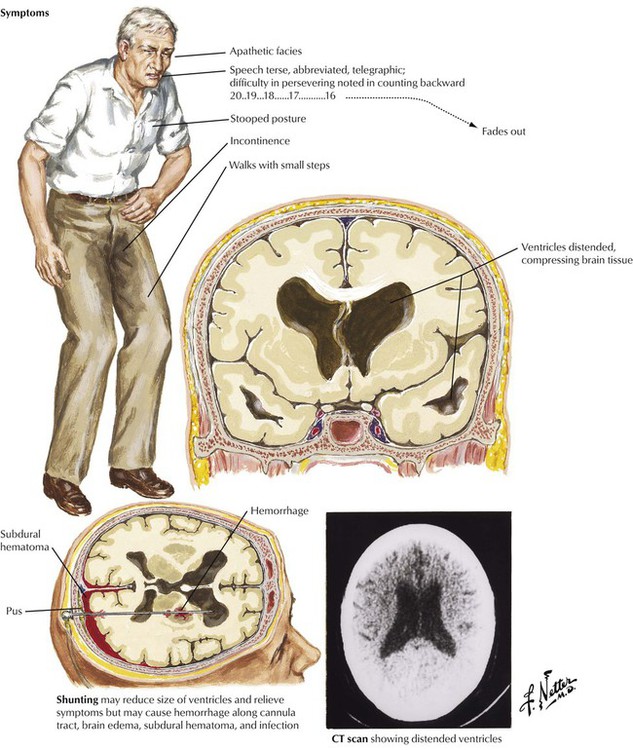

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus is a disease of the elderly that develops over a period of several months or more insidiously. Most symptoms relate to enlargement of the anterior horns and loss of frontal lobe white matter. The clinical course is dominated by the triad of dementia, abnormalities of gait, and incontinence. If more CSF is produced than is absorbed, the ventricles and subarachnoid space become distended with CSF. Conditions that cause scarring of the piarachnoid membranes, such as meningeal infection, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or bleeding from past traumas, can cause hydrocephalus by decreasing the effectiveness of CSF absorption. However, in most elderly patients, communicating hydrocephalus has no easily identifiable cause.

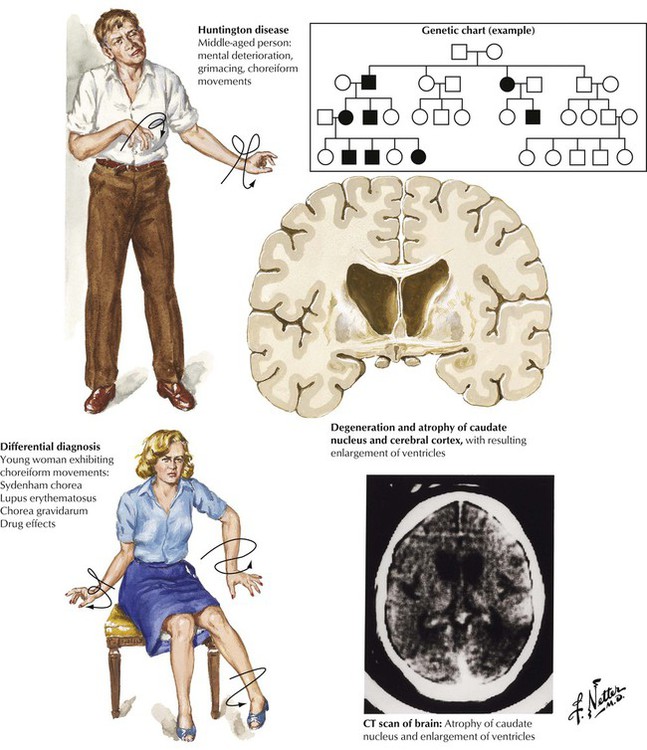

Chorea is a term applied to rapid, complex, and varied movements of the body, especially the distal limbs. The differential diagnosis includes Sydenham chorea (acute rheumatic fever), systemic lupus erythematosus, chorea gravidarum (in pregnant women), drug effects, and Huntington chorea. Abnormal facial and limb movements, behavioral disturbances, and progressive dementia characterize Huntington disease, a degenerative disorder with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, with onset usually after the age of 40 years. The genetic mutation is carried by approximately 50% of the offspring of an affected individual. Autopsy reveals severe shrinkage of the caudate nucleus and cortical atrophy, especially of the frontal lobes.

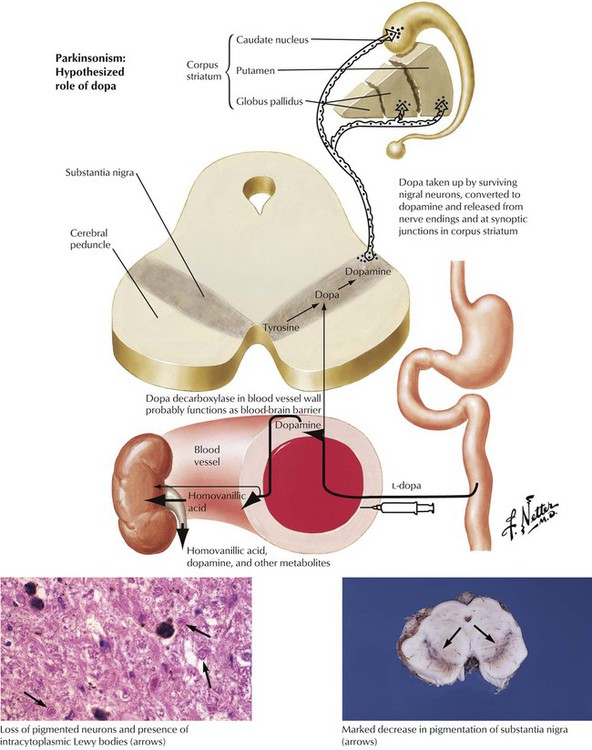

Parkinsonism is a clinical syndrome characterized by impaired facial expression, slow voluntary movements, intention tremor, and characteristic gait with increasingly shortened, quickened steps. Impairment of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system is the underlying mechanism for the variety of conditions that produce the characteristic motor alterations. The pathology of Parkinson disease is characterized by degeneration of the substantia nigra with loss of the normal black pigmentation. Microscopic examination shows loss of neuronal cells and mild reactive gliosis in the substantia nigra, the locus ceruleus, the substantia innominata, and certain reticular nuclei. Many neurons contain distinctive eosinophilic spherical inclusions known as Lewy bodies.

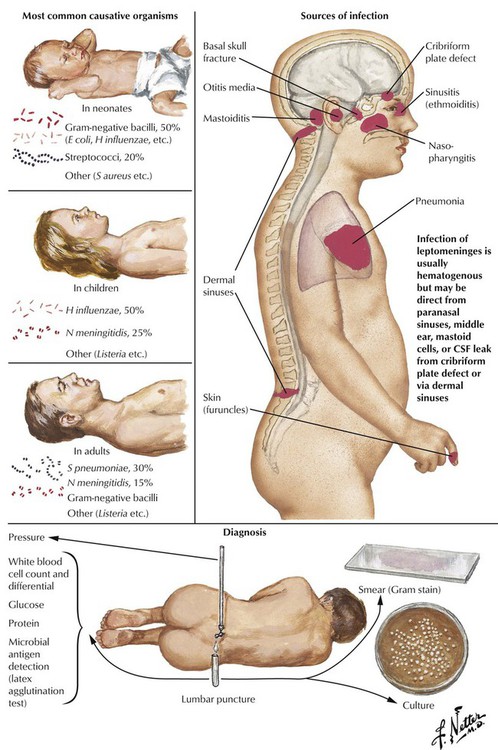

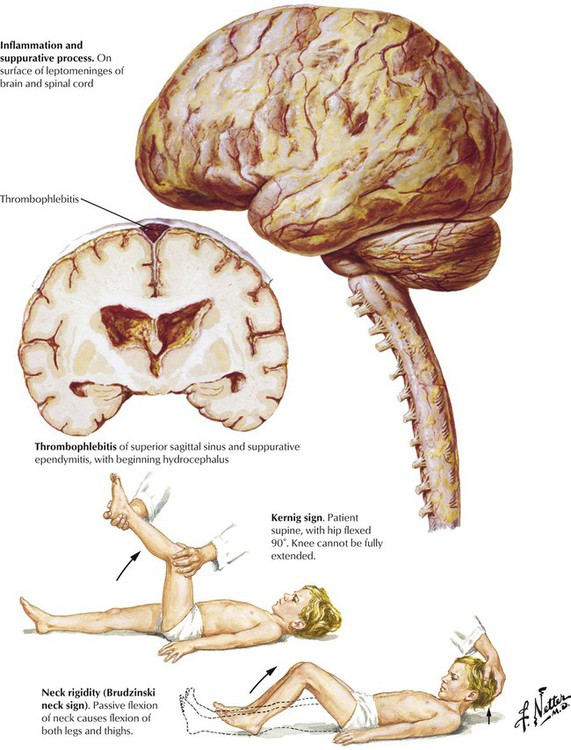

Meningitis, or inflammation of the leptomeningitis and CSF, is usually caused by spread of a microorganism through the bloodstream from another site, such as the ears, the throat, the lungs, or the skin. Less frequent causes include contiguous spread of infection from the paranasal sinuses or the mastoid process or from penetrating trauma. The most likely infectious agents vary according to the age of the patient. Predisposing factors include defects causing leakage of spinal fluid, sickle cell anemia, alcoholism, cirrhosis of the liver, immunodeficient states, and asplenia. The disease usually progresses rapidly with symptoms including diffuse headache, fever, vomiting, stiff neck, lethargy, and diminished consciousness. A spinal tap with examination and culture of the CSF can provide definitive information to distinguish suppurative (bacterial) meningitis from other conditions. Meningitis can progress to produce severe neurologic damage, particularly if there is obstruction to drainage of CSF, cerebral arteritis, or thrombophlebitis.

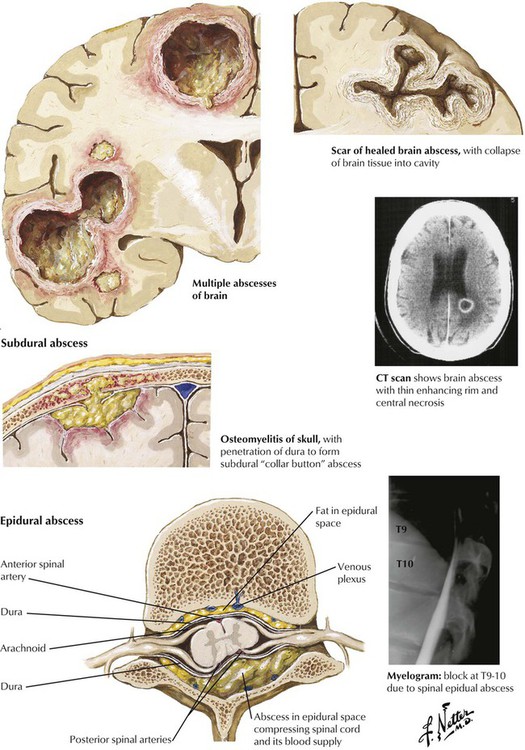

Brain abscesses develop from hematogenous spread from a distant site of infection, particularly the heart (infectious endocarditis, congenital heart disease) and the lungs (bronchiectasis, chronic infections), from direct extension from an adjacent focus, such as a middle ear infection, or from penetrating trauma. Direct extension is the usual cause of subdural abscesses as well. Patients with brain abscesses present with severe headache usually accompanied by focal neurologic signs and often with fever. Responsible microbes are usually aerobic bacteria, most commonly streptococci, staphylococci, or gram-negative bacteria, but some cases involve anaerobic microorganisms or multiple organisms. An epidural abscess is a purulent or granulomatous process within the spinal epidural space that may encroach on the spinal cord, the nerve roots, and the nerves. Predisposing conditions include vertebral osteomyelitis and hematogenous spread of infections from the skin, the mouth, and the respiratory tract.

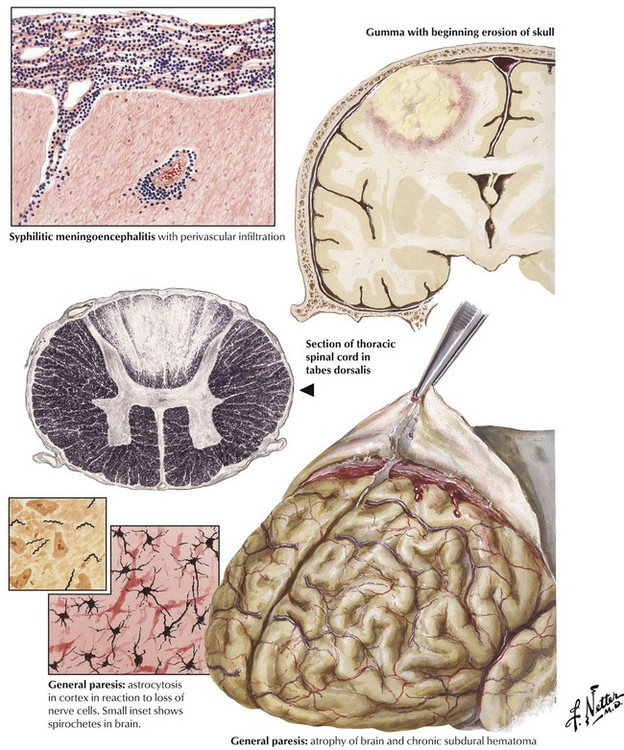

Syphilis of the central nervous system occurs late in the course of a primary infection with Treponema pallidum in approximately 10% of patients. Invasion of the spirochete elicits a lymphocytic inflammatory process involving the meninges, the brain, and the spinal cord (meningoencephalitis), often accompanied by endarteritis and degenerative and gummatous lesions. Neurosyphilis can occur in several forms: syphilitic meningitis, meningovascular syphilis, tabes dorsalis, dementia paralytica (general paresis), and gumma (rare). CSF analysis shows modest lymphocytosis, a moderately increased protein level, and a normal glucose level. Of key importance, results of serologic tests for syphilis, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test and the fluorescent treponemal-antibody absorption test, are positive in serum and CSF. Prolonged treatment with penicillin is indicated to arrest the progression of disease.

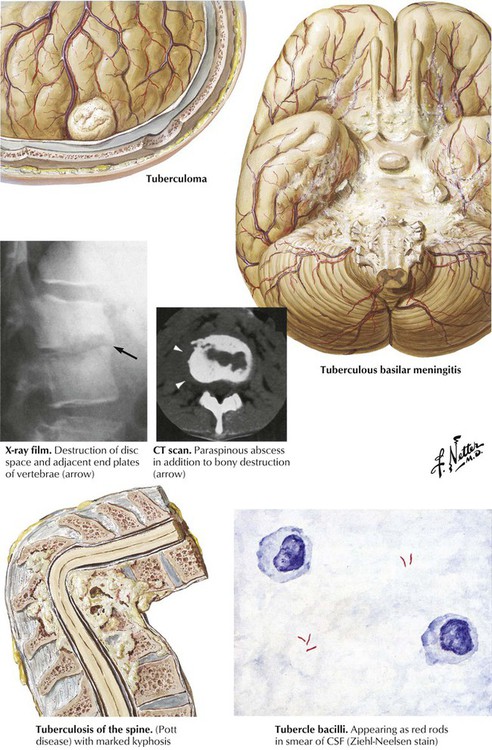

Tuberculous meninigitis usually begins with a focus of meningeal seeding by hematogenous spread followed by discharge of infection into the subarachnoid space from the caseous focus. The meninginitis sometimes results from contiguous spread from a tuberculoma or parameningeal granuloma with rupture into the subarachnoid space. As the infection spreads, an intensive inflammatory reaction at the base of the brain leads to obliterative endarteritis with thrombosis of small vessels and secondary brain infarction, compression of cranial nerves, and obstruction of the flow of CSF. The clinical course of tuberculous meningitis is usually florid, with rapid progression to neurologic defects and coma. Classically, the CSF glucose level is low, the protein level is high, and the cell count is increased with predominantly lymphocytes. Acid-fast smears may be positive but often are not, so cultures must be performed. Other forms of tuberculous disease are the isolated tuberculoma and vertebral tuberculosis (Pott disease).

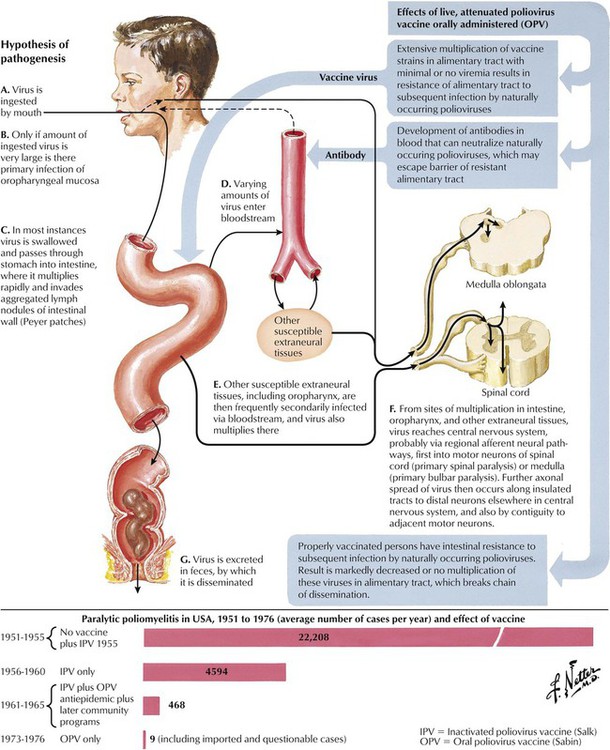

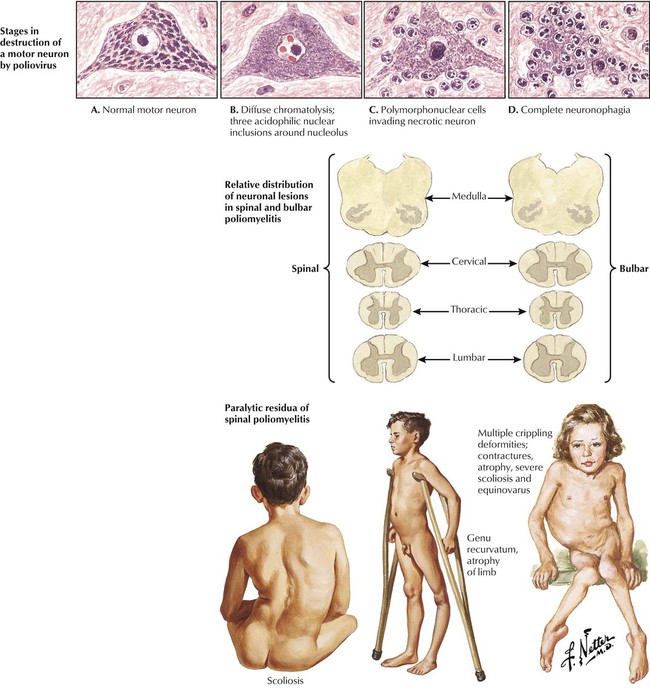

Poliomyelitis represents a well-characterized neurologic disease caused by poliovirus infection and a disease successfully prevented by vaccination. Poliovirus, an RNA virus of the picorna group of enteroviruses, is propagated by oral-fecal transmission. Poliomyelitis begins as an acute febrile illness. In a small minority of infected individuals, viremia is followed by propagation in the nervous system, leading to a lower motor neuron type of paralysis, which may be accompanied by respiratory and vasomotor disturbances caused by neuronal lesions in the medulla. Outcomes ranging from an abortive minor illness or nonparalytic illness to paralytic illness depend on individual susceptibility and the neurovirulence of the infecting virus. The incidence of paralytic polio in the United States has progressively and dramatically declined, initially after the introduction of the subcutaneously administered formalin-inactivated poliovirus vaccine (Salk type) and, subsequently, the live, attenuated oral poliovirus vaccine (Sabin type).

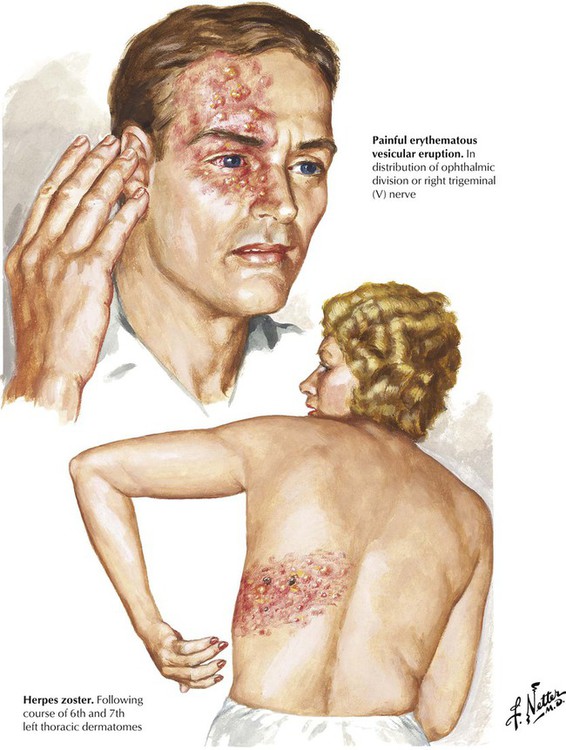

Herpes zoster (shingles), a relatively common infection of the peripheral nervous system, occurs most often in immunocompromised individuals. Herpes zoster is an acute neuralgia with a characteristic painful vesicular rash confined to the distribution of a specific spinal nerve root or cranial nerve. The primary site of infection is the dorsal root ganglion, and the infectious agent is the DNA-containing varicella-zoster virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox. The virus migrates up the peripheral nerve to the dorsal root ganglion after an attack of chickenpox and then remains dormant until an immunologic imbalance allows it to become active again. On reactivation, an acute inflammatory reaction occurs in the dorsal root ganglion, and the virus then spreads down the nerve root and the peripheral nerve to the skin, producing the characteristic rash. Patients with ophthalmic herpes zoster are at risk for blindness.

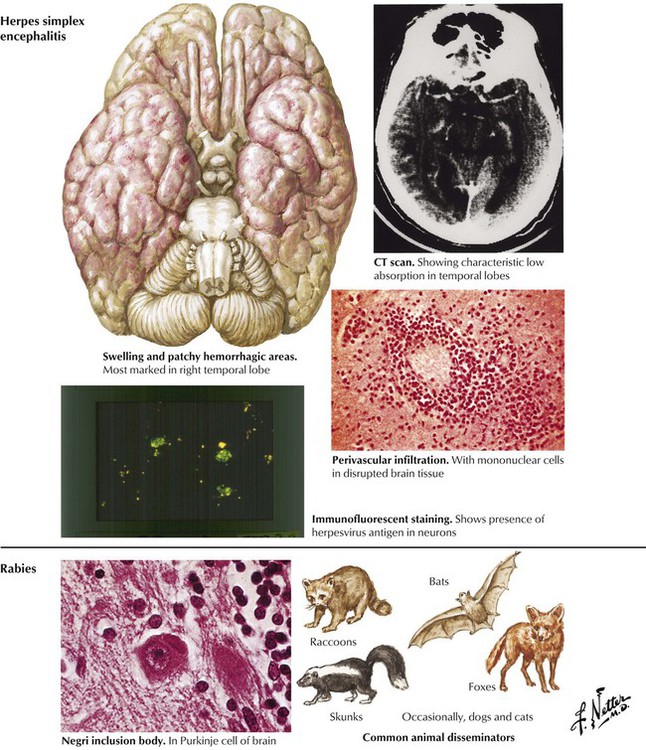

Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) is a relatively common and serious acute viral disease of the brain. The infection is associated with a high mortality, and survivors often have significant neuropsychiatric sequelae. Neonates usually are infected with HSV-2, and children and adults usually are infected with HSV-1. The virus likely reaches the brain via the olfactory tract or the trigeminal (V) nerve and leads to a primary infection or a subsequent reactivation event. Encephalitis most often involves the medial temporal and frontal lobes. The histologic features are hemorrhagic necrosis, inflammatory infiltrates, and neurons containing intranuclear inclusions. Rabies is an acute viral disease of the central nervous system caused by an RNA virus of the Rhabdoviridae family transmitted by inoculation of a wound contaminated by saliva of a rabid animal. Paralytic disease begins 1 to 3 months after infection. Although clinical manifestations are severe, neuropathologic findings consist of mild inflammation plus neurons showing the pathognomonic cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion, the Negri body.

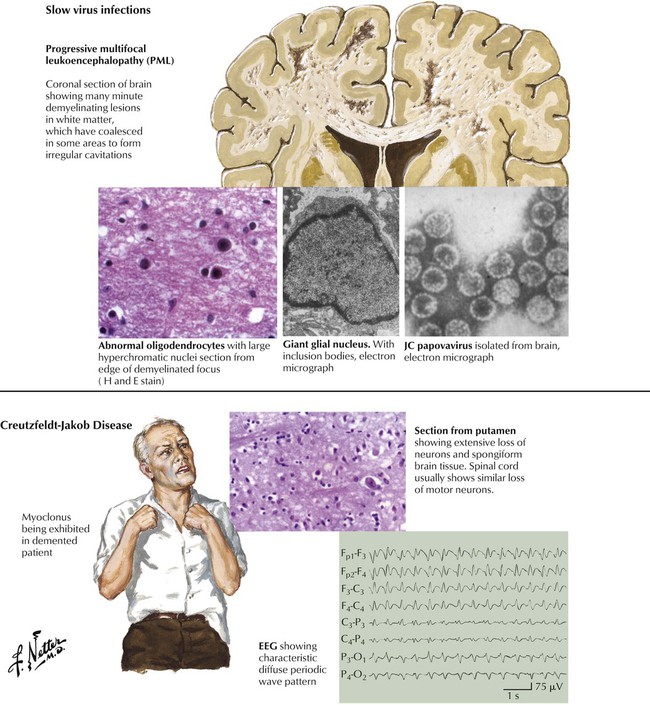

Slow virus infections refer to progressive and fatal neurologic syndromes that arise months or years after an initial viral infection. Immunosuppressed patients are particularly susceptible. Examples are progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy caused by the JC papovavirus and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis caused by reactivation of a measleslike virus. Spongiform encephalopathies are known to be caused not by a virus but by a unique mechanism involving mutated proteins called prions. The human diseases caused by these agents are Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which has a worldwide distribution, and kuru, linked to cannibalistic practices in the New Guinea highlands. The pathology of both diseases is characterized by neuronal loss, neuronal vacuolization, and astrocytosis without inflammatory infiltrates. The human form of mad cow disease is a variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. The clinical hallmarks are progressive dementia and myoclonus.

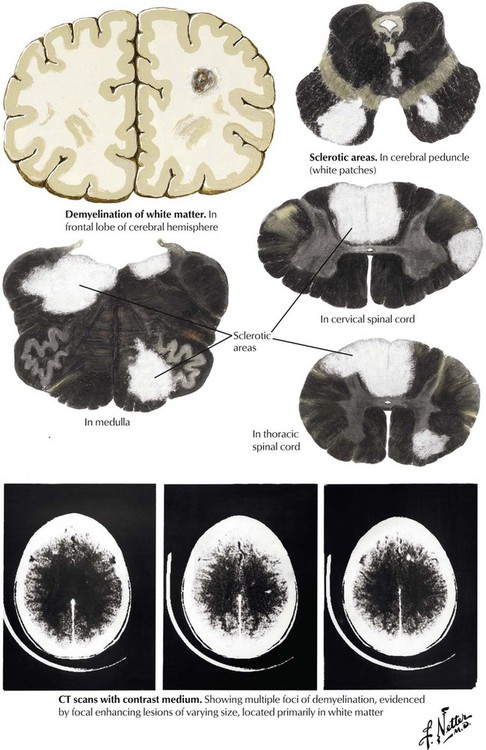

Multiple sclerosis is a relatively common disease that is characterized by clinical neurologic defects that are separated over time and are linked to the development of demyelinating lesions of the white matter that are separated spatially in the brain. Multiple sclerosis typically occurs in adults aged younger than 50 years and occurs approximately twice as frequently in women as men. The pathogenesis involves inflammation in response to an undefined trigger and possibly involving an autoimmune component. Lymphocytes and macrophages produce focal destruction of myelin and loss of oligodendroglia while sparing axons, and then microglia and astrocytes phagocytose the myelin. The resulting areas of demyelination with variable amounts of glial scar are known as plaques, and these lesions are the hallmark of the disease. The symptoms and signs of multiple sclerosis depend on the number and the location of the plaques. The course of the disease is characterized by multiple exacerbations and remissions and has highly variable outcomes.

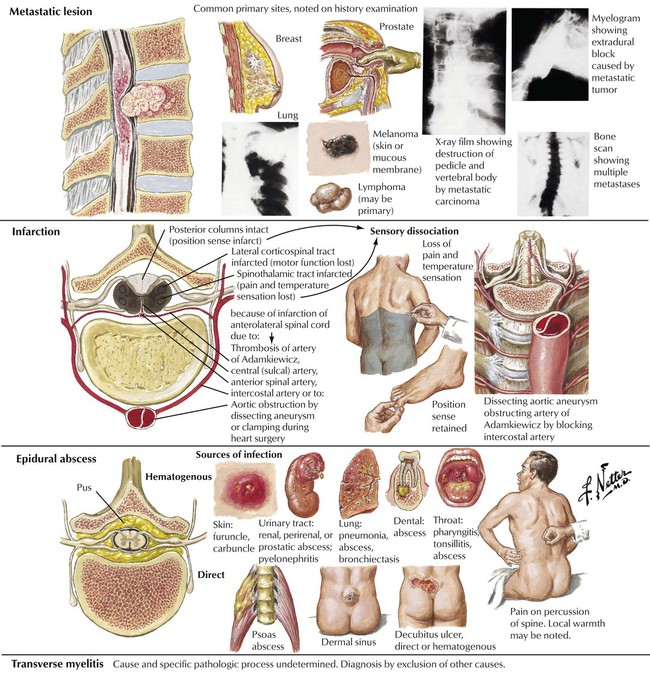

Acute spinal cord damage is often produced by a mass lesion that reaches a critical size in the confined space of the spinal canal. Differential diagnosis includes metastatic carcinoma, infarction due to a vascular occlusion, epidural abscess, and transverse myelitis. Transverse myelitis is a syndrome of acute spinal cord dysfunction due to a demyelinating disorder similar to acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of an acute spinal cord lesion may prevent paraplegia.

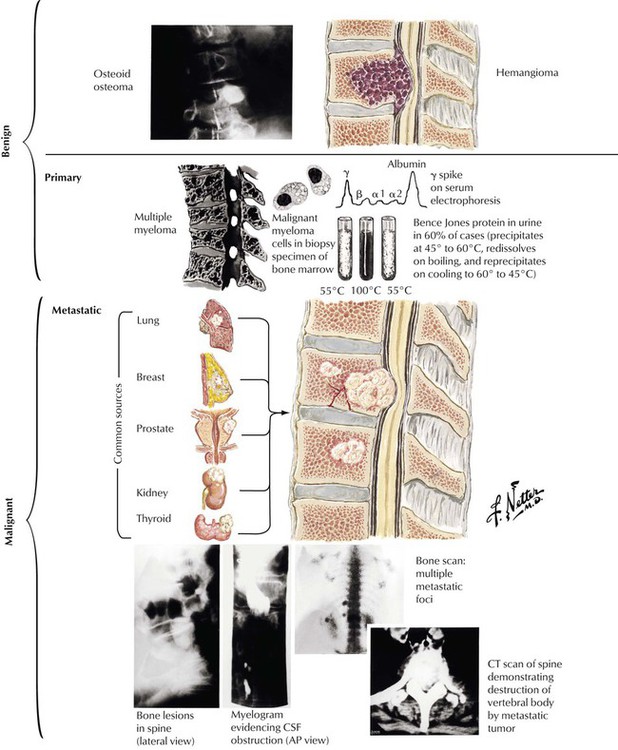

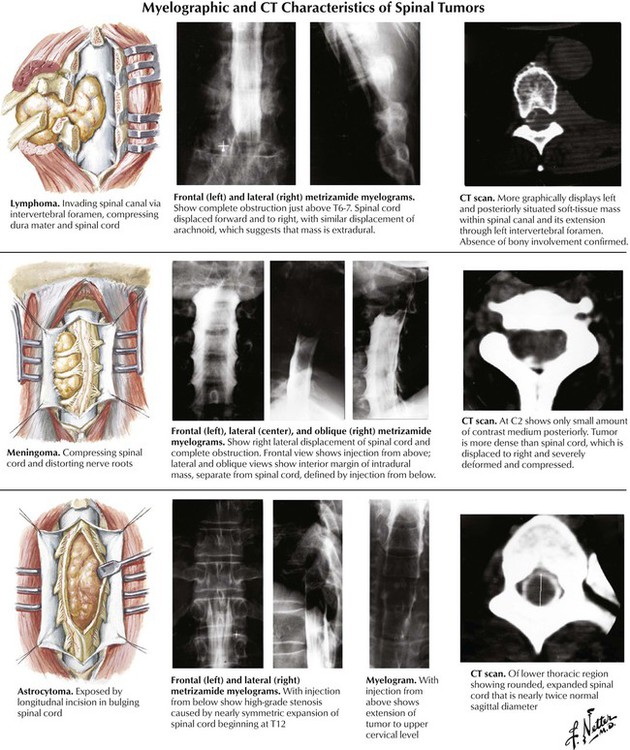

Tumors involving the spine are found external to the spinal cord (extradural tumors) or they involve the spinal cord (intradural). Extradural tumors are usually metastases to the spine that invade the epidural space. Most occur via hematogenous spread, but direct extension from extravertebral soft tissue also occurs. The most common primary tumors are lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and thyroid. Most produce osteolytic lesions in the vertebrae, but lesions of prostatic cancer are often osteoblastic. There also are primary bone tumors such as osteogenic sarcoma and giant cell tumor and the hemangioma of bone. Multiple myeloma is a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells that typically produces multiple osteolytic lesions in bone. The neoplastic clones typically produce a monoclonal γ-globulin component detectable in serum and in urine as Bence Jones protein.

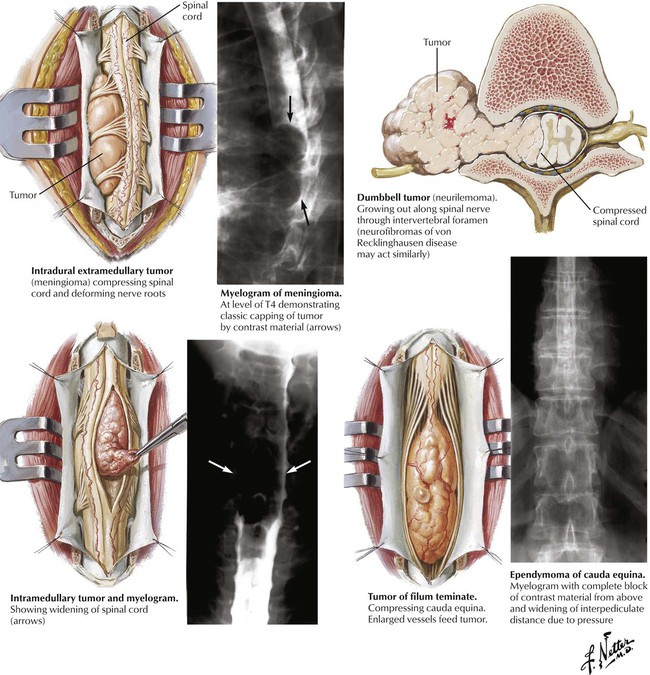

Intradural extramedullary tumors arise in the meninges and include the isolated benign meningioma and neurilemmoma and neurofibromas associated with neurofibromatosis. Progressive compression of the spinal cord can lead to local back pain and radicular pain and eventually cause serious spinal cord defects. Intramedullary tumors usually involve a discrete short segment of the spinal cord but may be more extensive, involving much of the length of the spinal cord. The 2 most common intramedullary tumors are the astrocytoma and the ependymoma. Intradural tumors of the lumbar spine can involve the specialized structures of this region, the conus medullaris, the filum terminale, and the cauda equina.

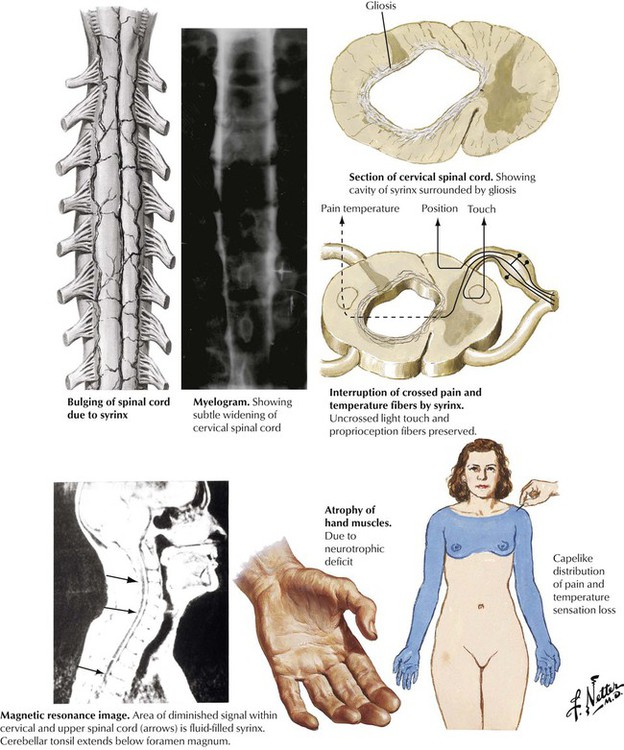

Syringomyelia is a rare disorder produced by the development of a cylindrical cavity, or syrinx, in the central area of the spinal cord, most frequently in the cervical and upper thoracic segments. The pathogenesis is poorly understood but seems to be developmental, degenerative, or both in nature. Other defects may be present, including the Arnold-Chiari malformation. Gradual expansion of the syrinx in the central area of the spinal cord produces neuronal and nerve tract damage. Symptoms usually develop in adults aged 20 to 50 years. The classic sign of syringomyelia is a dissociated loss of pain and temperature sensation in the upper extremities with preservation of light touch sensation and proprioception without motor deficits. The disease is characterized by progressive incapacitation due to spinal cord damage.

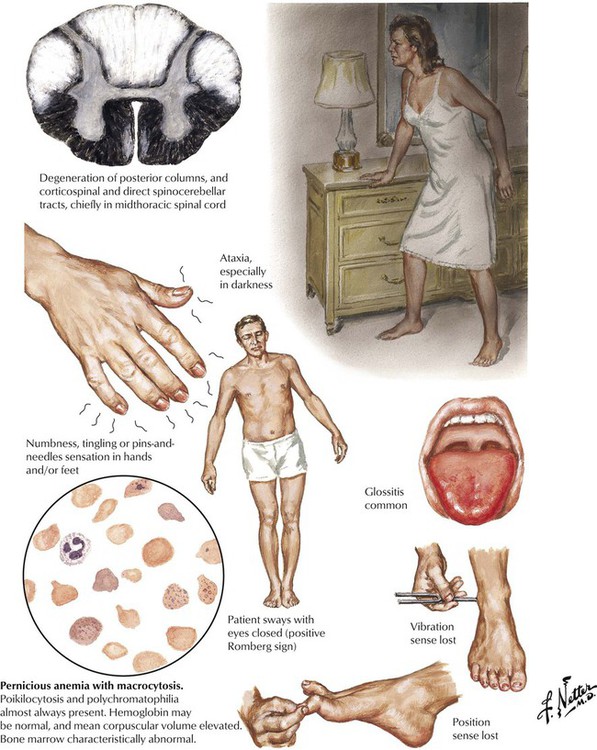

Subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord is a process of degeneration of the posterior and lateral tracts of the spinal cord resulting from vitamin B12 deficiency. Most cases are the result of pernicious anemia due to an autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis leading to an absence of intrinsic factor needed for vitamin B12 absorption or, less often, from other conditions in which vitamin B12 absorption is impaired or its dietary intake is insufficient. The most common neurologic symptoms relate to involvement of the posterior columns with loss of the sense of vibration of particular diagnostic significance. Lateral column dysfunction usually occurs later. The neurologic signs and symptoms may precede the appearance of anemia. Folate ingestion may mask the anemia but may not prevent the progressive neurologic damage. Proper diagnosis and administration of B12 is needed to prevent permanent neurologic damage.

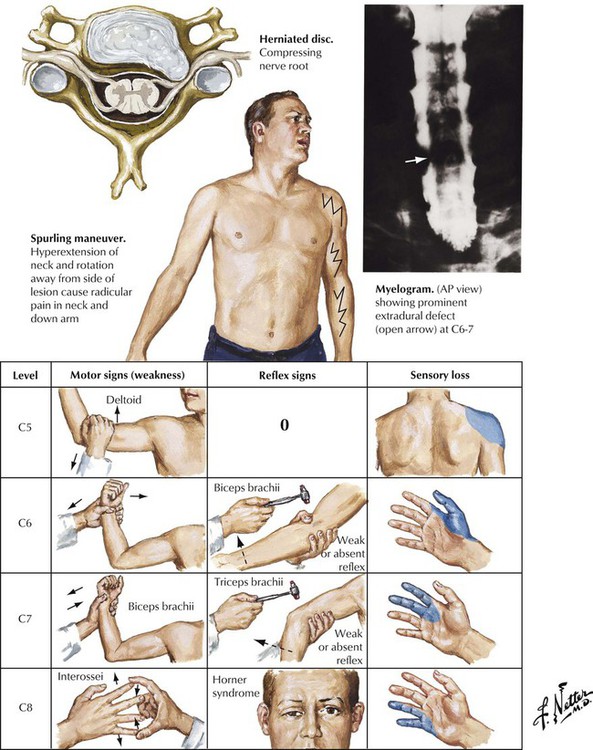

Cervical disc herniation is a common disorder usually caused by degenerative disease (osteoarthritis) rather than trauma. Severe degenerative cervical disc disease (spondylosis) can result in rupture of an intervertebral disc or osteophytes developing on the vertebrae from osteoarthritis. Osteophytes or ruptured discs produce symptoms when they compress the spinal cord or nerve roots against posteriorly located structures of the spinal column, including the posterior nerve root foramen and the ligamentum flavum. Neurologic examination focusing on motor, reflex, and sensory findings in the upper extremities usually reveals a diagnostic grouping of symptoms and signs pointing to the location of the pathologic lesion. Surgical therapy is indicated only if conservative management is unsuccessful.

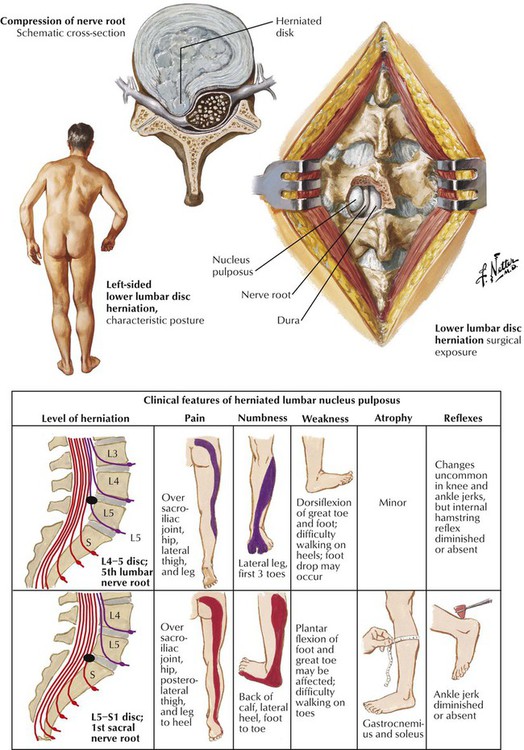

Lumbar disc disease causing low back pain and nerve root pain is a common problem. The lumbar spine is a compact anatomical region composed of the 5 lumbar vertebrae and the sacrum, which are separated by the normally tough and compact intervertebral discs. With aging, the fibrocartilaginous disc degenerates and fragments; in the process, the adherence to the adjacent vertebrae is weakened. Mechanical forces can then cause the fragments to move, usually in a posterolateral direction toward the exit sites of the nerve roots. Pain and neurologic deficits develop from the ensuing pressure on the nerve roots. The various clinical features of a herniated nucleus pulposus of a lumbar intervertebral disc are shown here. Surgical intervention is often needed to relieve the problem.

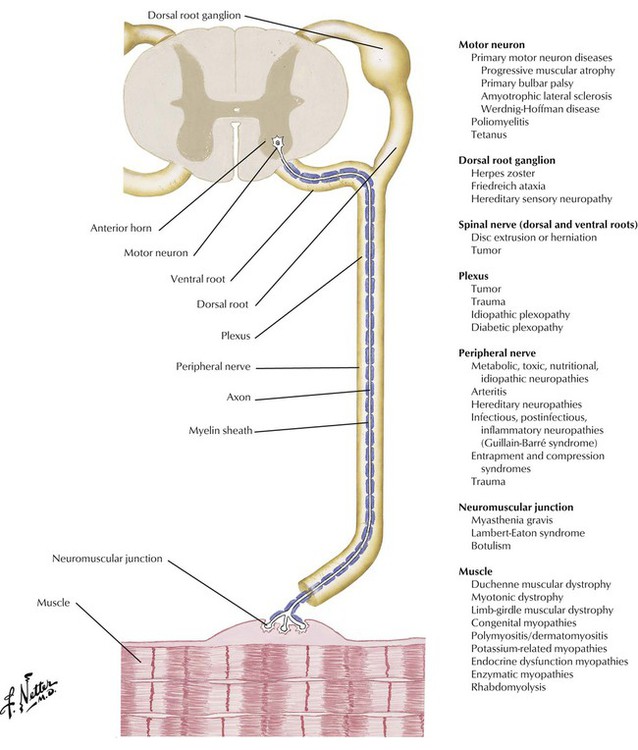

The motor neurons of the spinal cord and the cranial nerves serve as the final common path for transmission of neural impulses through the axon and neuromuscular junction to the skeletal musculature. Diseases of the motor-sensory unit typically occur without impairment of mental function. In diseases of the neuromuscular junction, particularly in myasthenia gravis, cranial nerve abnormalities, especially those producing diplopia or ptosis or both, occur frequently. Bulbar motor neuron disease may present with dysphagia. Careful evaluation of gait and the pattern of muscle weakness are important in the differential diagnosis. In general, the deep tendon reflexes are either normal or reduced in most disorders of the motor-sensory unit. A sensory examination and pattern of sensory deficit also are important to determine the underlying pathology because sensation is usually intact in motor neuron disease, neuromuscular junction disorders, and primary myopathies, whereas distal sensory loss is typical of peripheral neuropathies.

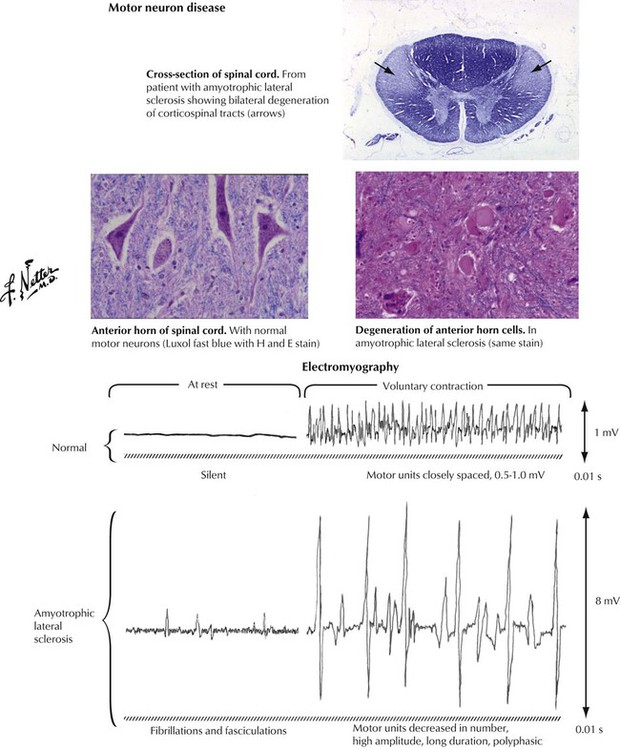

Primary motor neuron diseases have varied clinical manifestations. Patients may present with progressive muscular atrophy (primary asymmetric lower motor neuron disease), primary bulbar palsy (dysfunction of motor neurons originating in the brainstem), or the syndrome of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (upper motor neuron disease with corticospinal tract involvement superimposed on primary muscular atrophy or primary bulbar palsy). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig disease) typically presents with manifestations of lower motor neuron disease, particularly dysfunction of muscle movements. These manifestations eventually join with symptoms of degeneration of the corticospinal or corticobulbar tract, including muscle spasticity. Electromyography reveals a characteristic pattern of abnormalities.

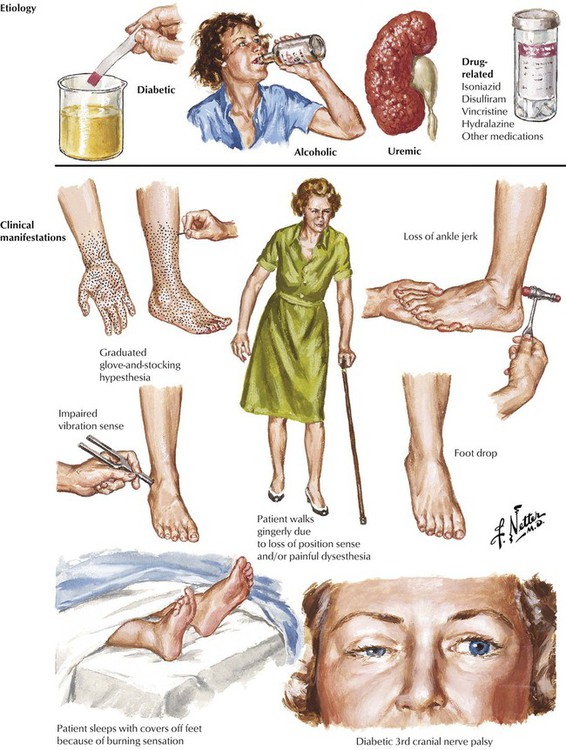

A variety of metabolic, toxic, or nutritional conditions can produce subacute or chronic peripheral neuropathies that tend to involve multiple nerves in a symmetric pattern. Some cases are idiopathic, and in others, the family history suggests a hereditary basis. Typically, the patient presents with symptoms of symmetric numbness, tingling, burning, or constriction of the extremities and a cautious gait. Physical examination usually shows changes first evident in the legs and feet. There is a symmetric hyporeflexia, with distal weakness. Pathologic changes on nerve biopsy may be nonspecific and consist of patchy foci of demyelination and axonal degeneration or may show more specific findings, such as amyloid deposits and, in patients with diabetes, hyaline arteriolosclerosis.

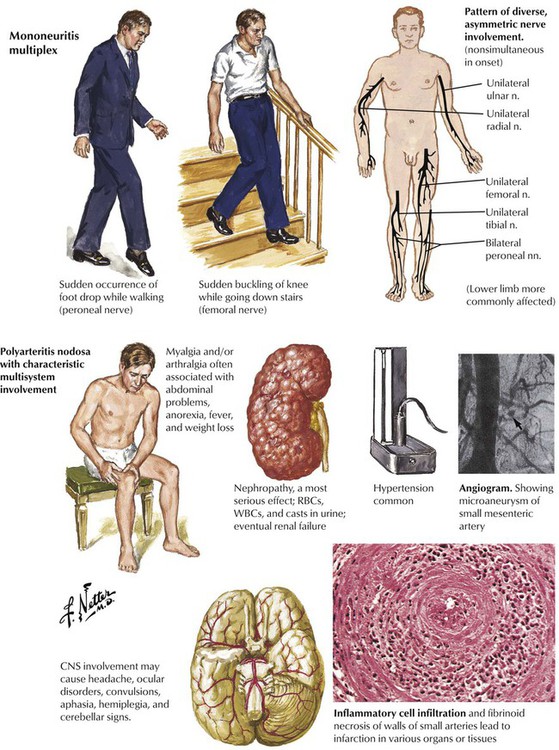

There are a number of conditions that compromise the circulation to a specific nerve acutely. The neurologic presentation resembles the acute onset of pressure or traumatic lesions but without evidence of such lesions. The acute onset of foot drop is a common presentation. The illness progresses by recruitment of additional peripheral nerves, usually in an asymmetric fashion. The presentation may even mimic a diffuse, symmetric polyneuropathy but with a much more rapid course. Acute lesions are more commonly caused by disorders affecting small-sized arterioles, and this occurs relatively often in patients with diabetes. Also to be considered are PAN, an acute necrotizing vasculitis with multisystem involvement, and the arteritises associated with systemic lupus erythematosus or Churg-Strauss syndrome. Other diagnostic considerations are cardiac embolic lesions from bacterial endocarditis or atrial myxoma; dysproteinemias, a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with some carcinomas; and leprosy.

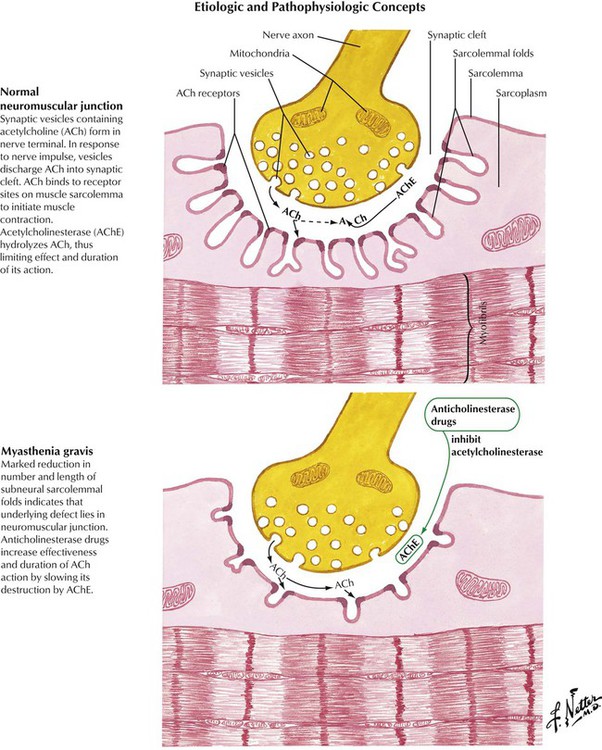

Myasthenia gravis is an acquired autoimmune disease characterized by production of antibodies to acetylcholine receptors linked to marked reduction of junctional folds and decrease in acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction, thereby impairing the transmission of nerve impulses. Myasthenia gravis is frequently associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and pernicious anemia. Abnormalities of the thymus are common, which is manifest in most cases as thymic hyperplasia and in approximately 10% as a thymoma. Myasthenia gravis has a worldwide distribution and occurs in all age groups but with a strong female preponderance. Myasthenia gravis may be generalized or limited to ocular myopathy. There also are congenital, neonatal, and drug-induced forms. Lambert-Eaton syndrome is a condition resembling myasthenia gravis occurring as a paraneoplastic syndrome in patients with an underlying carcinoma, often oat cell carcinoma of the lung.

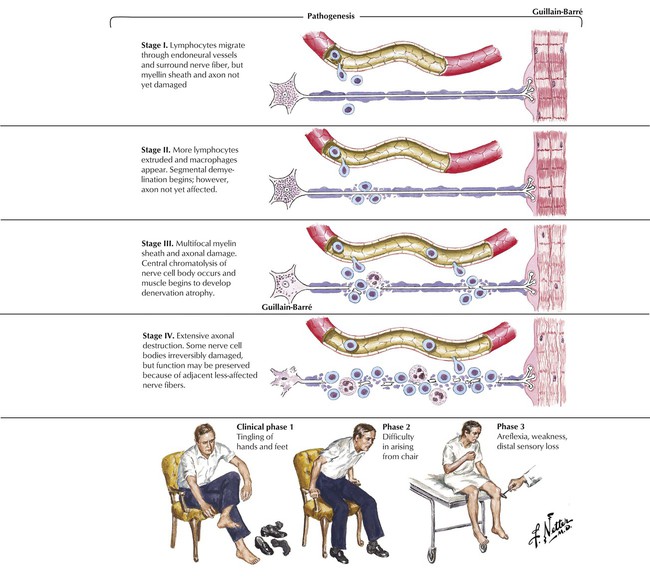

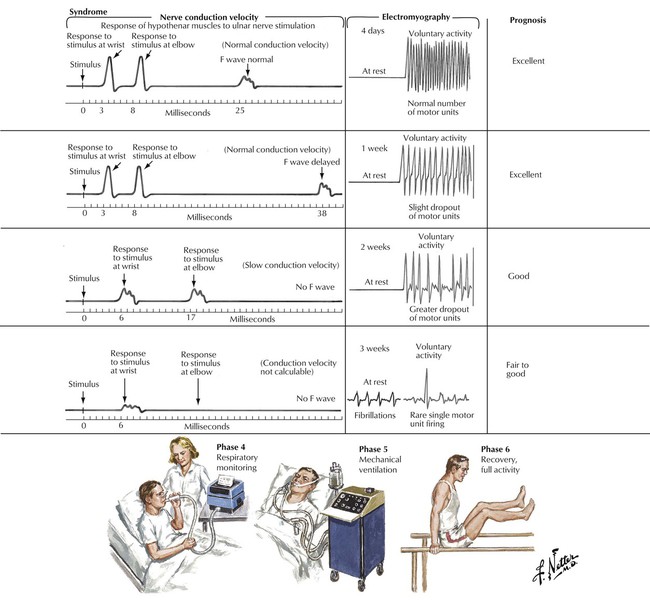

Guillain-Barré syndrome is an acute, rapidly progressive, ascending paralysis that spreads from the distal limbs to involve more proximal muscle groups, including facial and respiratory muscles. The disease affects motor function primarily, leading to total loss of reflexes and function. Predisposing conditions include a recent viral infection in most patients or impaired immune function. The syndrome results from inflammatory attack of the peripheral nerves, probably triggered by an autoimmune reaction. The inflammation leads to demyelination and, in severe cases, secondary axonal damage. Patients may present with progressive symmetric paralysis with cranial nerve dysfunction, particularly Bell palsy, sensory ataxia, or pure autonomic dysfunction. Differential diagnosis includes acute spinal cord lesions; toxic, metabolic, or infectious processes; poliomyelitis; diphtheria; botulism; porphyria; and myasthenia gravis. Guillain-Barré syndrome is self-limiting in most patients.

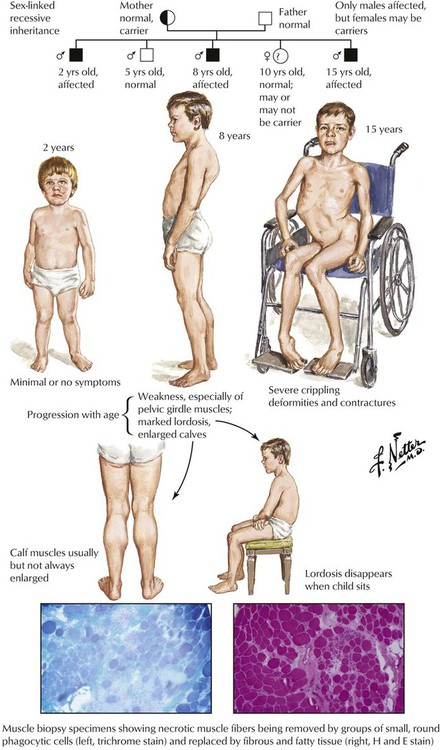

Muscular dystrophies are a heterogenous group of inherited diseases characterized by progressive muscle weakness due to progressive degeneration of skeletal muscle, often with onset in childhood. There are various inheritance patterns, including the most common X-linked pattern of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy, a milder variant. The disease is marked by progressive development of muscle weakness, especially of pelvic girdle muscles, marked lordosis, and enlargement of the calves, so-called pseudohypertrophy due to muscle swelling. Pathologic changes are those of multifocal muscle fiber degeneration and necrosis, removal of necrotic muscle by phagocytic leukocytes, regenerative changes in surviving muscle fibers, fibrofatty replacement of muscle, and muscle atrophy. The illness progresses relentlessly, and the majority of patients die during the late second or third decade of life.

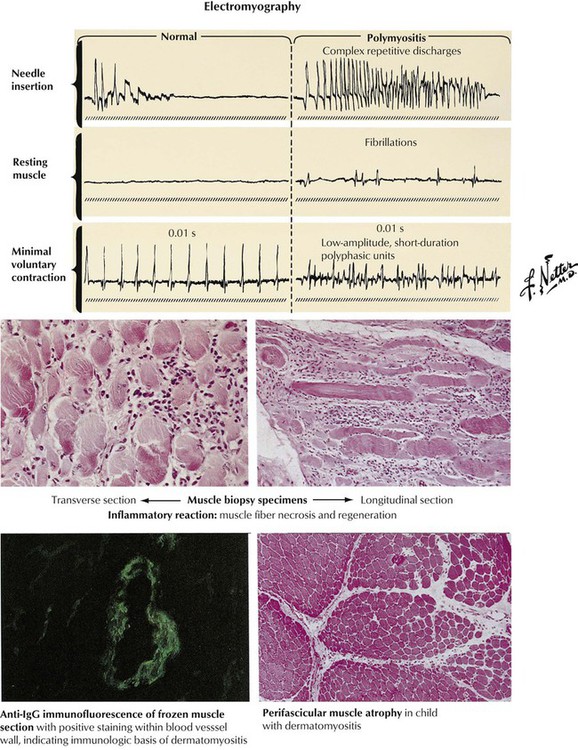

Polymyositis is a relatively common condition characterized by weakness of the proximal musculature with usual onset in middle-aged persons. Polymyositis seems to develop on an autoimmune basis, and it can be associated with other connective-tissue diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic vasculitis, or, occasionally, with an underlying malignancy. The onset is often insidious but may be rapid. Many patients have an accompanying rash, and the combination of conditions is known as dermatomyositis. In patients with recent onset of symmetric proximal muscle weakness, with or without a rash, the diagnosis of an inflammatory myopathy can be confirmed by evidence of increased serum markers of muscle damage, especially creatine kinase, typical electromyographic changes, and positive muscle biopsy with inflammatory cellular infiltrates and immunoglobulin deposits by immunofluorescence. The prognosis ranges from complete recovery to frequent recurrence to fatality in approximately 25% patients even with treatment with steroids.