Neoplastic and Infiltrative Diseases

Neil S. Prose, Richard J. Antaya

Introduction

Skin disorders characterized by infiltrative lesions can be present at birth or develop during the first few months of life. Some represent frank neoplasms, both benign and malignant, whereas others are the result of metabolic errors. In most instances, diagnosis is facilitated by skin biopsy, in which certain cell types can be identified by special stains and immunologic markers. Others require special enzyme assays for definitive diagnosis.1

Neoplastic disorders

Leukemia

Congenital leukemia is a rare hematologic disorder. Less than 1% of all childhood leukemia is diagnosed in newborns.2 The majority of neonates have acute myeloid leukemia (AML), while acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is less common. The most frequently occurring chromosomal abnormality in both congenital AML and ALL is a translocation involving the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene. To differentiate congenital leukemia from the several infectious and proliferative disorders that can easily mimic this condition, the following diagnostic criteria are employed:

1. The presence of immature white cells in the blood

2. Infiltration of these cells into extrahematopoietic tissues

4. The absence of chromosomal disorders that are associated with ‘unstable’ hematopoiesis (such as trisomy 21).3,4

Cutaneous findings

The cutaneous manifestations of congenital leukemia consist of petechiae, ecchymoses, and skin nodules. Leukemia cutis is seen in approximately 60% of patients with congenital leukemia. The firm nodules are usually 1–2.5 cm in diameter and blue to purple in color (Fig. 28.1). They are often widely spread over the skin surface, although congenital leukemia may present as a single nodular cutaneous lesion.5 Diffuse calcinosis cutis in an infant with congenital AML has been reported.6 Congenital AML may be manifested by ‘blueberry muffin’ lesions,7 and Darier’s sign has been observed.8 The clinical signs and symptoms include hepatosplenomegaly, pallor, lethargy, and respiratory distress. Lymphadenopathy occurs in some infants.

Diagnosis

Biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals a dense pleomorphic mononuclear cell infiltrate in the dermis and subcutaneous fat. Atypical mitotic figures may be present. The diagnosis of congenital leukemia can usually be confirmed by a complete blood count, bone marrow aspirate, and radiographs of the skull and long bones. In every case, cytogenetic studies must be performed to exclude the possibility of transient myeloproliferative disorder, which is usually associated with trisomy 21.9 This disorder is also associated with a diffuse vesiculopustular eruption (see Chapter 10).10,11

Treatment and course

Congenital leukemia is often fatal, with overall survival ranging from 10–25%.5 Treatment consists of intensive multiagent chemotherapy. The benefit of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains uncertain. Spontaneous remission of congenital leukemia cutis, usually without involvement of blood or bone marrow, has been reported.12–14

Leukemia in infancy

Leukemia occurring in infants under the age of 1 year bears many similarities to congenital and neonatal forms. Patients in this age group also have a high incidence of MLL rearrangements. Typical lesions include violaceous macules, nodules, and plaques. Patients with AML may present with larger purplish tumors, while those with ALL may develop numerous prurigo-like papules. The development of granulocytic sarcoma (formerly known as chloroma) in the periorbital skin of infants has also been reported.15

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH), a rare proliferative disorder, may be present at birth or may develop during the first few months of life. The estimated incidence of neonatal LCH is 9/1 000 000 in infants <1 year of age, with disease presentation during the first month of life in about 6% of those affected.16,17 The spectrum of clinical presentations, and the clinical course, is extremely varied and ranges from the simple presence of one or several nodules, widespread crusted papules and vesicles, to severe, progressive multisystem disease.

Cutaneous findings

The most frequent cutaneous presentation – particularly in infants and newborns – consists of multiple widespread vesiculopustules with umbilication and a hemorrhagic crust.18–23 Lesions tend to favor the scalp, trunk, diaper area, and skin folds (Fig. 28.2A). They may begin as subtle brown or pink papules, and evolve into crusted or purpuric lesions (Fig. 28.2B). Papular lesions may coalesce into areas of superficial ulceration with oozing, especially in intertriginous areas. Characteristic lesions also include fissures behind the ears, and crusting and oozing of the external ear canals. The scalp is a frequent site of involvement, and the coalescence of crusted and scaling lesions may lead to partial alopecia. Presentation as a ‘blueberry muffin baby,’ with cutaneous hematopoiesis, has been reported.24 Nodules and petechiae, which may involve the palms and soles, are also observed. Oral lesions are relatively common, and can develop before skin lesions. They may appear as superficial ulcerations or erosions, but these are often associated with underlying alveolar bone disease. Other oral manifestations include gingival bleeding, facial swelling, and pain. Premature eruption and loss of teeth, and destruction of alveolar bone are characteristic. Involvement of the vulva and vagina may also occur. Nail involvement consists of subungual pustules, paronychia, onycholysis, and longitudinal grooving. Permanent nail dystrophy may result.25

Congenital ‘self-healing’ langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

A multifocal congenital form of LCH, which has sometimes been called ‘Hashimoto–Pritzker disease’26 is characterized by papulonodular and papulovesicular skin lesions. Cases presenting with a solitary nodule have also been reported. These solitary skin nodules are usually red-brown and often have a hemorrhagic quality, ulceration, or crusting.27 Most affected infants have lesions at the time of birth without evidence of other organ system involvement (Figs 28.3, 28.4).26 Skin lesions typically resolve spontaneously, without sequelae but localized areas of scar or atrophy can occur.28–30 However, skin relapse, bone disease, late-onset diabetes insipidus, and even progression to severe LCH has been reported in children who present with congenital skin lesions.31

Extracutaneous findings

The majority of infants with all forms of congenital or neonatal Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis will show evidence of multisystem disease.31–33 Bone lesions are the most frequent noncutaneous manifestation. Findings may include asymptomatic lytic lesions, deformation, fracture, or medullary compression. The skull is a common site, and disease in that location manifests on X-ray as punched-out lesions in the cranial vault. Mastoid involvement may lead to mastoid necrosis, and destruction of the ossicles may result in deafness. Intercranial disease may cause exophthalmos and diabetes insipidus. Lymph node involvement is seen in a significant percentage of patients, and tends to occur in the cervical chain. Pulmonary disease may be associated with cough and tachypnea. Other findings include bullae formation and diffuse interstitial fibrosis. Invasion of the liver may cause mild cholestasis, but eventually evolve to sclerosing cholangitis. Severe fibrosis of the liver results in ascites, jaundice, and liver failure. Involvement of the spleen may worsen the severity of thrombocytopenia. Gastrointestinal disease is reported to occur in a small percentage of patients.34 Characteristic findings are vomiting, diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, and failure to thrive secondary to malabsorption. The most common endocrine manifestation is diabetes insipidus. This occurs most often in children with extensive disease and involvement of the skull. Langerhans’ cells may also infiltrate the thyroid and pancreas.

Diagnosis

Biopsy of a cutaneous lesion reveals a diffuse infiltration of histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and eccentric, indented nuclei. In some cases, the nuclei may appear pleomorphic or atypical. Positive CD1a and/or CD207 (Langerin) staining of the lesional cells is needed for a definitive diagnosis. Electron microscopy is no longer required since it is now known that the expression of Langerin correlates with the ultrastructural presence of Birbeck granules.35

Preliminary laboratory evaluation of the patient with biopsy-proven skin lesions must include a complete blood count (CBC), serum electrolytes, urine specific gravity, and assessment of liver function. Examination of the bone marrow may show the presence of increased histiocytes. Skeletal survey, chest radiographs, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine the extent of bone, pulmonary, liver, spleen, and CNS involvement.

Differential diagnosis

The pustular and intertriginous lesions of LCH in neonates and infants may be confused with candidiasis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis and scabies. Congenital LCH must also be differentiated from other neoplastic disorders, such as leukemia and lymphoma; from congenital infections, especially herpes simplex; and from those viral disorders associated with ‘blueberry muffin’ lesions.

Treatment and course

The majority of children with infantile LCH develop multisystem disease. The prognosis seems to be better in congenital ‘self-healing’ LCH, but multisystem disease is still possible, and such neonates must be followed to assure that they do not develop extracutaneous disease later on. Survival of infantile LCH in the past few decades has improved from 57% to 74%.16,35 Single-system disease has a significantly higher rate of survival (94%), but patients with initial liver involvement have a much poorer prognosis, with a 25% 5-year survival. In children with LCH limited to the skin (<5% of cases), a ‘wait and see’ approach should be accompanied by careful monitoring for disease progression. Children in this category may benefit from therapy with mild to moderate-strength topical corticosteroids. Children with multisystem disease are treated with chemotherapy; standard treatment is based on steroids and vinblastine.

Lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides is extremely rare in young children, but a number of cases have been well documented.36 The patients presented with widespread and persistent scaly plaques. Several cases were initially misdiagnosed as either atopic dermatitis or tinea corporis, leading to a significant delay in diagnosis.

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma

This form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma is characterized by large tumor cells that express CD30 antigen. Clinical presentations consists of papules, and plaques which may ulcerate. The rare occurrence of this disease during the first 2 years of life has been documented.37

Lymphomatoid papulosis

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic, recurrent disorder characterized by the presence of reddish brown papules and nodules. Progression to malignant forms of lymphoma is rarely reported. In one series of pediatric patients, including children under the age of 2 years, a benign course, accompanied by a predominance of CD8+ lymphocytes was observed.38

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma is extremely rare in infancy. Primary cutaneous lymphoblastic lymphoma, presenting with firm violaceous nodules with overlying telangiectasia, has been reported to occur in some children under the age of 2 years.39,40 Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, with purplish tender nodules in an acral distribution, has also been reported to occur in infancy.41,42

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening condition characterized by hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias and prolonged fever.43 Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms are frequent. Some children have been noted to have an evanescent macular and papular skin eruption, sometimes associated with episodes of fever (Fig. 28.5). Genetic HLH occurs in familial forms (FHLH), and in association with a variety of immune deficiencies.44 Acquired and genetic forms may both be triggered by infections.

Diagnosis is made by the detection of a non-malignant mixed lymphohistiocytic proliferation in the reticuloendothelial system, with evidence of hemophagocytosis. Without treatment, FLH is usually rapidly fatal. The immediate goal of treatment is suppression of the increased inflammatory response by immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory agents and cytotoxic drugs. Genetic cases can only be cured with stem cell transplantation.45

Infantile fibrosarcoma

Congenital/infantile fibrosarcoma is a rare tumor that occurs most frequently on the extremities. Lesions are seen less commonly on the head, neck, and trunk, and may also occur in the retroperitoneum.46 The tumor may be present at birth, or may develop during early infancy.

Diagnosis

MRI is useful in defining the extent of the lesion, but the diagnosis is largely based on histology. Histologic examination reveals a highly cellular fibroblastic proliferation, with sizeable vascular clefts and occasional myxoid degeneration and hemorrhagic necrosis.48 Analysis of the biopsy sample for the recurrent translocation t(12;15)(p13;q25) is highly recommended.49

Differential diagnosis

Clinically, infantile fibrosarcomas are easily confused with either hemangiomas or vascular/lymphatic malformations.50,51 Transient consumptive coagulopathy mimicking Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon has been reported, causing confusion with other vascular tumors (see Chapters 21 and 22).52 The differential diagnosis also includes rhabdomyosarcoma and infantile myofibromatosis.

Treatment and course

The risk of metastasis, especially in cutaneous lesions, is considerably lower in infants (approx. 8%) than in older patients.53 Treatment consists of wide local excision. Chemotherapy has been used in some patients to reduce the lesion mass preoperatively so as to avoid the need for mutilating surgery, and for lesions that are not resectable.54 Close follow-up to monitor for the presence of local recurrence and metastatic disease, is mandatory.55

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a fibrohistiocytic tumor with low metastatic potential and a high incidence of local recurrence. Congenital DFSP is rare, but a number of cases have been reported.56–58 Another neoplastic disorder, giant cell fibroblastoma, can also present in early infancy (Fig. 28.7). Some authors consider this to be a variant of DFSP; others consider it to be a separate entity, but believe that hybrids of giant cell fibroblastoma and DFSP may sometimes occur.

Cutaneous findings

Characteristically, DFSP begins as an atrophic plaque surrounded by an area of bluish discoloration. Over time, as the cellular proliferation extends into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissues, nodules develop on the plaque surface (Fig. 28.8). Similar to the lesions seen in older patients, congenital DFSP occurs most commonly on the trunk and proximal extremities.59 Giant cell fibroblastoma more typically presents during infancy as a slow-growing soft-tissue mass.

Diagnosis

Histologically, DFSP is characterized by the presence of spindle cells in a well-defined and uniform storiform pattern. Focal myxoid change and scarring may occur. Tumor cells express vimentin, but are negative for S100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen, and smooth muscle actin.60 Diagnosis can be facilitated by detection of the collagen type Iα1/platelet-derived growth factor β-chain fusion gene by means of reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction or fluorescence in situ hybridization.58

Differential diagnosis

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of congenital DFSP includes fibrous hamartoma of infancy, infantile myofibromatosis, lipoblastoma (see Chapter 27), and vascular tumors and malformations. Neurofibroma and fibrous histiocytoma may mimic DFSP histologically.

Treatment

Because of the high risk of recurrence, adequate surgical margins must be obtained. Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred approach in older children. However, in young infants, this can be difficult to arrange logistically in a child requiring general anesthesia for the excision, so wide excision is generally performed.61

Neuroblastoma

Cutaneous findings

Neuroblastoma is among the most common solid tumors of early childhood, and may present at birth or in early infancy.62 In stage 4, neuroblastoma cutaneous metastases present as bluish, firm papules and nodules on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 28.9). Several authors have reported that these lesions may blanch after palpation, and that the blanching persists for 30–60 min.63,64 This phenomenon has been related to the localized release of catecholamines. Periorbital ecchymoses, secondary to orbital metastases, may also occur.

Extracutaneous findings

Metastatic disease, characterized by fever, hepatomegaly, and failure to thrive, is often present at the time of diagnosis. The primary lesion is usually located in the upper abdomen, arising within the adrenal gland, and may be detected as an enlarging mass.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of the cutaneous lesions is based on histologic examination. The dermal or subcutaneous infiltrate consists of small cells with scanty cytoplasm and heterochromatic nuclei. Pseudorosettes and mature ganglion cells are present in differentiated lesions. Immunoperoxidase staining may establish the presence of neuron-specific proteins.

Although most cases of neuroblastoma are sporadic, autosomal dominant inheritance may occur. Concordance in monozygotic twins has also been reported.65 The location and extent of the primary lesion is most often established by computed tomography (CT) or MRI. Increased urinary catecholamines are present in the majority of patients.

Differential diagnosis

Clinically and histologically, the lesions of neuroblastoma must be differentiated from leukemia and lymphoma. In addition, the blueberry muffin appearance of some lesions may mimic congenital rubella or cytomegalovirus infection.

Treatment and course

The prognosis of neuroblastoma depends on the age of the patient and the extent of the disease (stages 1–4S). The survival rate at 2 years in children who are diagnosed under the age of 1 year exceeds 80%. In some patients, especially with stage 4S, spontaneous differentiation to neural ganglion cells and regression without treatment have been reported. The choice of treatment depends on staging and patient age, and consists of various combinations of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.66

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) presents most commonly as a tumor of the head and neck (Fig. 28.10A,B) There are two histologic subtypes: embryonal RMS, which is more common and usually has a better prognosis, and alveolar RMS, which is characterized by the t(2;13)(q35;q14) and t(1;13)(p36;q14) chromosomal translocations.67 An association between RMS and both neurofibromatosis type 1 and major congenital abnormalities has been observed.68 RMS arising in children with giant congenital melanocytic nevi has also been reported.69 A cutaneous origin of RMS is rare. Most often, extension of the tumor into the dermis results in the evolution of a nodule or plaque.70 Facial lesions are most common and these must be differentiated clinically from dermoid cysts, hemangiomas, and inflammatory disorders. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of small blue cells with occasional differentiation toward rhabdomyoblasts. The presence of staining for desmin, vimentin and muscle actin help to differentiate these lesions from neuroblastoma and lymphoma.71

Treatment is based on the extent of local, regional, and distant disease, and consists of a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Combined modality therapy results in a long-term survival of >50%.72

Rhabdoid tumor

Rhabdoid tumor is a rare and highly malignant neoplasm with rapid growth and early metastases. The skin may be the site of a primary tumor or of metastases from other locations (Fig. 28.10C). The majority of neonates are found to have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, and brain tumors are a frequent finding. Characteristic bluish cutaneous nodules may be located over the entire skin surface. The tissue of rhabdoid tumors has a characteristic genetic alteration in the region 11.2 of the long arm of chromosome 22 (22q11.2), characterized by the deletion or mutation of the hSNF5/SMARCB1/INI1 gene resulting in the loss or reduced expression of INI protein. The survival rate is extremely low.49,71

Malignant melanoma

Malignant melanoma is very rare in neonates and infants but can develop in several different clinical situations73–75:

1. Congenital malignant melanoma arising de novo. Malignant melanoma may present at birth as a nodular, darkly pigmented, rapidly growing skin lesion sometimes with ulceration.76,77 In these neonates, there is no clinical or histologic evidence of an underlying congenital melanocytic nevus, and there is no maternal history of melanoma (Fig. 28.11).

2. Congenital malignant melanoma arising in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus. In these patients, ulcerated and nonulcerated nodules may be present in the congenital melanocytic nevus and on adjoining skin. The presence of prenatal metastatic disease has been noted to occur in some children.78,79

4. Congenital malignant melanoma secondary to maternal melanoma. Transplacental transmission from a mother with metastatic disease may occur.80 Typically, the skin lesions are multiple pigmented macules, papules, and nodules, and there may be multiorgan involvement.

5. Spitzoid melanoma is a relatively rare subtype which shares histopathologic features with Spitz nevus.81 The prognosis is variable; Spitzoid melanoma with regional lymph node involvement and no further progression has been reported.82 However, some cases have resulted in a fatal outcome.

The diagnosis of malignant melanoma is made by excisional biopsy of the suspicious lesion, and the cellular and architectural features are similar to those seen in melanoma in older patients. However, a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors, with small round cell, spindled, neural, and epithelioid components, have been observed within congenital melanocytic nevi.77 In addition, histologic changes within a benign, congenital melanocytic nevus may include displaced large melanocytes within the epidermis, and heterogeneous patterns of melanocytic hyperplasia.78 In some cases, findings of this type have led to an incorrect diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Biopsies of congenital melanocytic nevi, especially in the neonate, must therefore be interpreted with caution.73,83,84

The evaluation of children with all forms of melanoma must include a complete evaluation for local and distant lymph node involvement. Metastases are most frequently seen in the CNS, bones, lungs, and liver.

Treatment is based on lesion thickness and the stage of the disease. Therapeutic options include lymph node dissection of enlarged draining regional nodes and chemotherapy for metastatic disease.79 Lesions arising de novo have an unpredictable prognosis, and long-term survival has been reported in children who developed both local recurrences and metastatic lesions. Melanomas arising in congenital melanocytic nevi appear to have a significantly worse prognosis. Congenital malignant melanoma secondary to maternal melanoma is usually fatal, but spontaneous regression has been reported to occur.80

Congenital teratoma

Congenital teratomas most frequently present as masses in the cervical, nasopharynx, or sacrococcygeal region.85 These are usually benign tumors, which are derived from elements of all three germinal layers, and which result in significant morbidity and mortality because of their location, size, and tendency to cause airway obstruction. Approximately 10–20% of SCT may contain primitive germ cell tumor components, and can evolve to actual malignancy. This risk increases significantly with age at diagnosis. The diagnosis requires complete pathologic examination of the entire resected tumor for malignant change. The differential diagnosis includes dermoids and lymphatic or vascular birthmarks. Treatment consists of complete surgical excision.86

Infiltrative disorders

Mastocytosis

Mastocytosis refers to a disease spectrum with varied presentations, all characterized by infiltration of benign mast cells (MC) in the skin or other organs. ‘Mastocytosis in the skin’ or MIS is the designation given to patients who have cutaneous MC lesions and have not been evaluated for systemic involvement (e.g., bone marrow examination), typically the case in children. A total of 55% of cases develop during the first 2 years, and an additional 10% develop before puberty.87 Cases developing after puberty are classified as adult onset. Both sexes are affected equally. MIS is subclassified into maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MPCM, also known as urticaria pigmentosa, UP), solitary mastocytoma, and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (DCM). However, many display overlapping features. MPCM is the most common clinical manifestation of mastocytosis. Solitary mastocytoma is less common, although it may be underreported, and DCM, the most severe form, is rare. Most cases are sporadic; however, there are several reports of MPCM affecting multiple family members, and some believe DCM can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.87–89 Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP) has been reported rarely in the neonatal period, with onset typically during adulthood.

Cutaneous findings

Most patients with MIS exhibit Darier’s sign, which is the development of an urticarial wheal and flare after firm stroking of lesional skin. This cutaneous finding represents the response to physical disruption of the granular contents of mast cells, particularly histamine. Rarely, flushing and hypotension have resulted from stroking of a large lesion or from surgery. Some patients display dermatographism, the formation of linear urticarial plaques following scratching of uninvolved skin. However, this nonspecific finding also occurs in up to 5% of the general population. A variety of physical stimulants and drugs can evoke mast cell degranulation, resulting in urtication, bulla formation, or systemic manifestations (flushing, hypotension, or shock) (Box 28.1).

Pruritis is typical, although many patients have no symptoms. It may be periodic or unremitting. Excoriations may be observed. In children less than 2 years old, vesicles and bullae can develop, and may be observed in all forms of cutaneous mastocytosis except telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. The tendency to blister diminishes over 1–3 years. In one series, generalized flushing was observed in 65% of patients with all forms of the disease.91

Solitary mastocytoma

Solitary mastocytoma most often appears in the first 3 months of life. It presents as one isolated, skin-colored to light brown, 1–5 cm, oval to round macule or slightly elevated papule, nodule or plaque (Fig. 28.12). In patients with limited lesions, typically 1–3, the term solitary mastocytoma may be used. Some lesions have a pink or yellow hue. Any cutaneous surface may be affected, but the trunk, upper extremities, and neck are favored locations. Most new lesions appear within 2 months of the initial lesion, more can develop over time and individual lesions may enlarge for several months.

Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MPCM)/urticaria pigmentosa

MPCM, or urticaria pigmentosa, generally develops between 3 and 9 months of life. The lesions appear as multiple, fixed, tan-brown, hyperpigmented macules and papules which can become widespread but usually are discrete and scattered. In rare cases, nodules or skin lesions coalescing into plaques with increased skin markings may develop (Fig. 28.13). Early lesions of MPCM may mimic recurrent urticaria until pigmentation becomes apparent. Any cutaneous surface may be affected, including mucous membranes, but most are on the trunk. Additional lesions of MPCM may develop for several months after the initial diagnosis is made.

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (DCM) is characterized by widespread infiltration of mast cells throughout the skin (Figs 28.10–28.12, 28.14). It presents in the first 3 years of life, and is characterized by normal-appearing, or generalized thickening and palpable edema of the skin, with or without the presence of typical MPCM lesions. The skin may be normal in color or display a reddish-yellow hue. The first sign of DCM is most often serous and hemorrhagic bullae with secondary erosions, sometimes following minor trauma. Severe dermatographism with resultant bullae and flushing may also occur.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans (TMEP)

Infantile TMEP presents with congenital or acquired asymptomatic, 1–4 cm, sharply defined, round or oval, telangiectatic, red-brown patches that resemble small capillary malformations. The patches blanch with pressure, but Darier’s sign is reportedly negative. The few documented cases have remained stable over time, and multiple family members can be affected.92

Extracutaneous findings in mast cell disease

Most infants with MIS do not have evidence of extracutaneous disease, but the risk increases with extent of cutaneous disease or symptoms such as flushing or recurrent diarrhea. Outside of the skin, the bone marrow is most often affected. Mast cell hyperplasia in lymph nodes, spleen, liver, bone or GI tract occurs rarely.93 Associated symptoms in infants is variable and commensurate with local or systemic MC-mediator release or organ dysfunction from MC infiltration of organs. Signs and symptoms include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bone pain, headache, hypotension, and shock. Prolonged bleeding in the skin and GI tract may occur, and is more frequent in infants with DCM. In these children, heparin from mast cells acts as a local anticoagulant. Elevated levels of circulating histamine, which stimulates gastric acid secretion, may result in gastric ulceration and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.94 Children with DCM have the highest incidence of visceral mast cell disease and associated systemic manifestations. MPCM in infants is rarely associated with visceral involvement, and visceral involvement does not appear to occur in children with solitary mastocytomas. The incidence of allergic disease is not increased in children with mastocytosis, but the severity of allergic reactions is increased and the risk of anaphylactoid reactions (e.g., to hymenoptera stings) is also increased.

Serum tryptase level is the best screening test for extracutaneous disease in the setting of extensive cutaneous disease or signs or symptoms of more widespread disease. If serum tryptase is persistently elevated (i.e., >20 ng/ml with normal being ~5 ng/ml) and systemic mastocytosis is clinically suspected, bone marrow evaluation should be considered.95 The optimal cutoff for baseline serum tryptase levels in children with MIS that predict the need for daily anti-mediator therapy, hospitalization, and ICU management is 15.5 ng/ml, and 30.8 ng/ml respectively (for sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 95%, and 100% and 96%, respectively).96,97

Etiology and pathogenesis

The cause of mastocytosis is unknown. However, activating mutations in the c-kit proto-oncogene have been identified in many patients, more so in adult than childhood cases. C-kit encodes for KIT, the membrane receptor for stem cell factor, and is expressed on mast cells, melanocytes, and hematopoietic stem cells. These mutations likely contribute to the characteristic proliferation of mast cells and hyperpigmentation of the skin seen in cutaneous mastocytosis, as well as the myeloproliferative diseases observed in some patients with mastocytosis.98

Diagnosis

The clinical presentation and characteristic cutaneous lesions usually allow for easy diagnosis. Skin biopsy should be performed when the diagnosis is unclear or when bullae are the main feature. Histopathologic criteria for the diagnosis of MIS include the presence of large clusters (15 cells each) of MCs or scattered MCs exceeding 20 cells per high-power (×40) field.99 Toluidine blue, Giemsa or MC-specific stains for c-kit (CD117) and tryptase can assist with identification of MCs. Bullae, when present, are subepidermal. Baseline serum tryptase levels, which tend to correlate with BSA involvement, may be useful in predicting infants at high risk of serious systemic symptoms.94 Clinical evidence of extracutaneous mastocytosis should guide any additional diagnostic studies (ultrasound, bone and liver/spleen scans, GI endoscopy, skeletal survey, and bone marrow evaluation).100 The usefulness of studies performed empirically is limited, and they do not appear to provide any prognostic information.87

Differential diagnosis

Mastocytomas should be differentiated from xanthomas, juvenile xanthogranulomas, café-au-lait macules and congenital nevi. Infestation with Sarcoptes scabei presenting with pruritic, red-brown nodules that exhibit a Darier’s sign may be mistaken for mastocytosis. Differentiating characteristics include more severe pruritus, lack of other lesions with other morphologies (e.g., paucity of macules and plaques commonly observed with MPCM), and distribution favoring covered and intertriginous areas in scabetic nodules.101 Where bullae are prominent or lesions are atypical, biopsy is indicated to differentiate mastocytosis from the immunobullous diseases, epidermolysis bullosa, or other infiltrative disorders (see Chapter 11).

Treatment and care

There is no curative treatment for pediatric mastocytosis, however the course in most cases is benign and the prognosis generally favorable. Solitary mastocytomas have not been reported to progress to systemic involvement.100 More than 50% of childhood cases of MPCM/UP resolve by adolescence, and the remainder experience a marked reduction in cutaneous symptoms.91,102 Of the patients whose disease persists into adulthood, 15–30% develop indolent systemic involvement, which is similar to the rate observed in adult-onset disease.91 Children presenting with congenital bullous MPCM or DCM have a higher risk for sudden death, usually from circulatory collapse.103

Treatment is aimed at reducing pruritus and, in some children, minimizing blister formation. The regular use of H1 antihistamines such as hydroxyzine or cetirizine is effective in treating pruritus, bullae, flushing, and abdominal pain. The addition of H2 blockers and oral disodium cromoglycate may be effective for patients with gastrointestinal signs or symptoms.104–106

Cutaneous mastocytomas may be treated with a short course of ultra-potent topical steroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors, and very problematic lesions may be excised. Rare instances of circulatory collapse as a result of systemic histamine release should be treated with careful fluid management and intravenous epinephrine.106 A self-injectable epinephrine device may be prescribed for children with a history of such episodes.87 PUVA therapy is effective for severe forms of MIS.107 Aggressive forms of MC respond partially to interferon-α or cladribine and there are positive anecdotal reports using tyrosine kinase inhibitors.95 Parents should be provided with a list of substances that potentially stimulate mast cell activity and which should therefore be avoided or given with caution (Box 28.1).90

Infantile systemic hyalinosis and juvenile hyaline fibromatosis

Infantile systemic hyalinosis (ISH) and juvenile hyaline fibromatosis (JHF) are rare, progressive, autosomal recessive diseases. They are allelic and represent part of a spectrum, rather than two distinct entities. Clinical manifestations which are noted at birth or in early infancy include papular and nodular skin lesions (Fig. 28.15A), skeletal and soft tissue lesions, gingival hyperplasia (Fig. 28.15B), joint contractures (Fig. 28.15C), and growth retardation.

Cutaneous findings

Several distinct characteristic skin lesions are observed in JHF. Small, skin-colored, pearly papules are found predominantly on the ears, neck, and paranasal folds, where they may coalesce to form thin plaques (Fig. 28.15A). Translucent-appearing larger papules and nodules are found around the nose, behind the ears, and on the tips of digits. These may have a gelatinous consistency. Papillomatous perianal lesions, resembling condylomata, have been observed in some patients.108

Extracutaneous findings

The most consistent and earliest extracutaneous manifestation of JHF is joint flexion contracture, especially of the knees and elbows. Many patients become severely disabled by these progressively severe contractures. Ultrasound evaluation of affected joints reveals distinctive alterations such as irregular cortical surface of MCPs and PIPs, osteophytes and bone erosions, and increased synovial fluid, even in infancy.109 Gingival hypertrophy is seen in nearly all patients, and the majority have osteolytic bone lesions and osteoporosis.110 JHF generally does not involve the viscera; however, there is considerable clinical and histologic overlap with the more severe disease of infantile systemic hyalinosis (ISH). In ISH, there are hyaline deposits in multiple organs, recurrent infections, often persistent diarrhea, and death within the first 2 years of life.108 Intellectual development is normal at both ends of the spectrum.

Etiology and pathogenesis

JHF and ISD are caused by mutations in the gene encoding capillary morphogenesis protein-2 (CMG-2), an integrin-like cell surface receptor for laminins and type IV collagen.111,112 The nature of the hyaline deposition is still not clear but may be composed of increased type VI and decreased type I collagen.113 On routine histology, the dermal papules show thinning of the epidermis and a dermis occupied by abundant, amorphous, PAS-positive, diastase-resistant material containing wavy filamentous elements. Cells with oval or spindle-shaped nuclei are embedded in this stroma, imparting a chondroid appearance. These fibroblastic cells often display PAS-positive cytoplasmic vacuoles. Ultrastructurally, the fibroblastic stromal cells display a hyperplastic and dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum with collections of smooth-surfaced cisternae filled with tangled microfilaments.108 Osteoporosis and osteolytic bone lesions are observed on radiographic examination of most patients. Routine laboratory evaluations are normal.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis should first include Winchester syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive condition that has many overlapping features with JHF, including joint contractures, dwarfism, hypertrophic lips and gingivae, severe osteoporosis, thickened leathery skin, and corneal opacities.114 Lipoid proteinosis may be distinguished from JHF by a distinctly different histology, a characteristic hoarse cry, and a more benign clinical course.

Treatment and course

The course is progressive. Excluding those most severely affected with hyaline material in the viscera, most patients survive into adulthood with severe physical deformities due to joint contractures, delayed motor development, and skin nodules that recur after surgical excision. Treatment, which is unsatisfactory, includes excision of skin lesions, repeated gingivectomy, and systemic corticosteroids for joint symptoms. At least one patient has been treated with interferon-α, with some reduction and softening of the smaller fibromas only (Ruiz-Maldonado and Duran, pers comm).

Farber disease

Farber disease, or Farber lipogranulomatosis, is a rare, progressive, autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease that leads to the accumulation of ceramide in tissues. The disorder primarily involves the musculoskeletal, respiratory, integumentary, and nervous systems of affected infants, and onset occurs in the first year of life.115 It presents in early infancy with a characteristic clinical triad of subcutaneous nodules, progressive painful and deformed joints, and progressive hoarseness.

Cutaneous findings

The characteristic cutaneous features include multiple subcutaneous nodules, flesh-colored papules, nodules, or tumors, especially near joints. Coarse facial features and xanthoma-like papules on the face and hands have also been reported. The resultant granulomatous inflammatory lesions are common findings which may be due to decreased apoptosis of inflammatory cells secondary to increased intracellular ceramide.116

Extracutaneous findings

Painful, deforming joint swelling with restriction of movement, particularly of the distal interphalangeal and metacarpal joints, is characteristic. Infants frequently exhibit marked failure to thrive, recurrent infections, a hoarse cry attributed to laryngomalacia, dyspnea, noisy breathing, and hyperirritability. Impairment of cognitive development, seizures, hepatosplenomegaly, macroglossia, recurrent fevers, and hyporeflexia are variably present.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Farber lipogranulomatosis is caused by a mutation in the gene ASAH1, which encodes for lysosomal acid ceramidase, with resultant progressive accumulation of ceramide in tissues. The characteristic clinical presentation and the detection of low levels of acid ceramidase are diagnostic of Farber disease. Light microscopic examination of skin and other affected tissues is nonspecific, demonstrating foam cells and a granulomatous infiltrate. This inflammation is hypothesized to be due to altered receptor-mediated apoptosis by intracellular ceramide accumulation.117 Several characteristic structures are observed ultramicroscopically, probably resulting from the accumulation of ceramide in cells. Curvilinear tubular bodies (comma-shaped, tubular structures consisting of two single membranes separated by a clear space) are observed in dermal fibroblasts among other affected cells. Banana bodies (variably membrane-bound structures that have a spindle and usually curved shape) are found predominantly in Schwann cells of peripheral nerves.116

Diagnosis

Radiologic examination reveals diffuse osteopenia, underdevelopment of terminal phalanges, and reduced long bone diameters.117 The diagnosis should be confirmed by detection of deficient lysosomal acid ceramidase activity in leukocytes, fibroblasts, or other tissues.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes metabolic storage diseases, particularly other mucolipidoses, malignant histiocytosis, and infantile systemic hyalinosis. Some cases have been misdiagnosed as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis because of the severe joint involvement seen early in the course.

Treatment and course

Most patients die of progressive neurologic deterioration early in the first decade of life. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was successfully performed in four patients without CNS involvement (type 2/3 disease), but allogeneic bone marrow transplant failed to halt the progression of Farber disease with CNS involvement (type 1).117 Various other treatments, including corticosteroids and radiotherapy, have been attempted and are ineffective. The potassium–titanyl–phosphate (KTP) laser has been used for treatment of severe oral lesions.118

Because transmission is autosomal recessive, genetic counseling is mandatory. Prenatal diagnosis, performed by assaying acid ceramidase levels in skin cells cultured from amniotic fluid, is now possible.119

Mucopolysaccharidoses

The mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) are a heterogeneous group of rare lysosomal storage disorders that display several variable clinical features, including coarse facies, skeletal abnormalities, mental retardation, corneal clouding, and hepatosplenomegaly. The degree of progression varies among the diseases, as does the constellation of clinical and laboratory findings. Each disease results from the deficiency of one specific lysosomal enzyme, but all are characterized by accumulation of mucopolysaccharides (glycosaminoglycans) in lysosomes and excessive amounts of mucopolysaccharides in the urine.120 Sanfilippo syndrome is the most common, and has an incidence of about 1 : 25 000. This is contrasted with Sly syndrome, of which only 40 cases have been reported worldwide.121

Cutaneous findings

The most characteristic cutaneous feature, manifest in all types of MPS, is coarse, thickened skin. This cutaneous alteration combines with underlying craniofacial abnormalities to impart coarse facial features. Patients have a thick nose with a depressed nasal bridge, thick tongue and lips, short neck, and macrocephaly. The severity of the facial abnormalities is variable, and the most striking features are observed in Hurler and Hunter syndromes. Coarse facies may not be present in young infants.122 Patients also display variable degrees of coarse hair and generalized hirsutism.

Apart from Sanfilippo syndrome, which presents with synophrys, Hunter syndrome is the only MPS that regularly presents with specific cutaneous findings. Children with Hunter syndrome may develop firm, discrete or coalescing ivory-colored papules on the arms or symmetrically distributed between the angles of the scapulae and the posterior axillary lines. This same finding was described in a patient with Hurler–Scheie syndrome.123 Another finding occasionally reported in Hunter syndrome is usually widespread dermal melanocytosis (see Chapter 24).

Extracutaneous findings

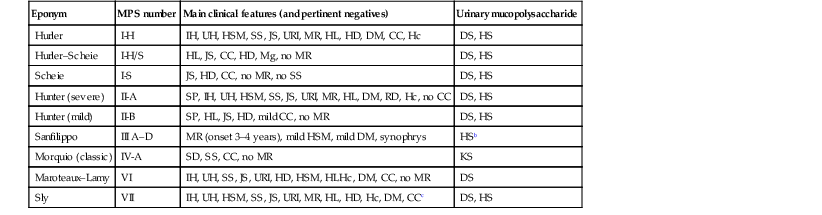

Infants may appear normal at birth, but usually develop characteristic findings in the first few years of life. Each disease has its own array of clinical findings; however, the most important extracutaneous features are mental retardation, deafness, hyperactivity/behavior problems, stiff joints, skeletal dysplasia, kyphoscoliosis, corneal clouding, valvular and coronary heart disease, hepatosplenomegaly, noisy breathing, and lower respiratory tract infections. Table 28.1 lists the cardinal characteristics and pertinent negative findings for each disorder. The skeletal abnormalities in the MPS are referred to as dysostosis multiplex and comprise the following elements: large, thickened skull with premature closure of lambdoid and sagittal sutures; shallow orbits; enlarged J-shaped sellae; and anterior hypoplasia of the lumbar vertebrae. In addition, the long bones display enlarged diaphyses, irregular metaphyses, and poor development of the epiphyseal centers.

TABLE 28.1

Classification and features of the mucopolysaccharidosesa

| Eponym | MPS number | Main clinical features (and pertinent negatives) | Urinary mucopolysaccharide |

| Hurler | I-H | IH, UH, HSM, SS, JS, URI, MR, HL, HD, DM, CC, Hc | DS, HS |

| Hurler–Scheie | I-H/S | HL, JS, CC, HD, Mg, no MR | DS, HS |

| Scheie | I-S | JS, HD, CC, no MR, no SS | DS, HS |

| Hunter (severe) | II-A | SP, IH, UH, HSM, SS, JS, URI, MR, HL, DM, RD, Hc, no CC | DS, HS |

| Hunter (mild) | II-B | SP, HL, JS, HD, mild CC, no MR | DS, HS |

| Sanfilippo | III A–D | MR (onset 3–4 years), mild HSM, mild DM, synophrys | HSb |

| Morquio (classic) | IV-A | SD, SS, CC, no MR | KS |

| Maroteaux–Lamy | VI | IH, UH, SS, JS, URI, HD, HSM, HLHc, DM, CC, no MR | DS |

| Sly | VII | IH, UH, HSM, SS, JS, URI, MR, HL, HD, Hc, DM, CCc | DS, HS |

a Some subtypes omitted.

b May be missed due to small amount.

c Large variability of phenotypes observed.

CC, corneal clouding; DM, dysostosis multiplex; DS, dermatan sulfate; Hc, hydrocephalus; HD, heart disease; HL, hearing loss; HS, heparan sulfate; HSM, hepatosplenomegaly; IH, inguinal hernia; JS, joint stiffness; KS, keratan sulfate; Mg, micrognathism; MR, mental retardation; RD, retinal degeneration; SD, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia; SP, skin papules; SS, short stature; UH, umbilical hernia; URI, upper respiratory tract infections.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Each type of MPS is caused by a deficiency of a specific lysosomal enzyme responsible for the degradation of mucopolysaccharides. This deficiency results in excessive accumulation of the mucopolysaccharides: dermatan sulfate, heparan sulfate, and keratan sulfate throughout the body. The deficient enzyme has been elucidated for each disease, and the genetic loci for several have been mapped.124 All have an autosomal recessive inheritance, except for Hunter syndrome, which is X-linked recessive. Excluding an increased incidence of Hunter syndrome in the Jewish population in Israel, and Morquio syndrome in French-Canadians, MPS appear to affect all ethnic groups equally.

Diagnosis

The testing of urine for glycosaminoglycans is the basis for screening patients suspected of having MPS. If screening tests are positive for glycosaminoglycans, a quantitative analysis should be performed to confirm the presence of MPS. The type and quantity of urinary glycosaminoglycans, combined with the child’s clinical presentation, are used to determine the most appropriate enzyme assay to establish definitively the specific type of MPS.120 The enzymatic diagnosis should be determined in all patients in whom MPS is suspected. Lysosomal enzyme analysis may be carried out using serum, leukocytes, or cultured cells. In all the MPS, histopathologic examination of skin with Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or Giemsa stain reveals metachromatic granules in fibroblasts, and occasionally in keratinocytes, and in the secretory and ductal cells of eccrine glands. In addition, the cutaneous papules, mostly seen in Hunter syndrome, exhibit extracellular dermal deposits of metachromatic material.124

Differential diagnosis

The mucolipidoses are the most important group of diseases to be differentiated from the MPS. I-cell disease (mucolipidosis II) shares most of the clinical features of Hurler syndrome, but patients with I-cell disease do not exhibit urine mucopolysaccharides or acceleration of skeletal growth around 1 year of age.

Treatment, course, and management

The natural course of the more severe forms is progressive, and death resulting from respiratory or cardiac complications often occurs during the second decade. Some types, such as Scheie syndrome, have a normal life expectancy. Bone marrow transplantation lessens the severity and slows the progression of most cases.121,125 Treatment of patients with MPS I using enzyme replacement therapy with recombinant human α-l-iduronidase reduces lysosomal storage in the liver and levels of urinary glycosaminoglycan excretion, and improves respiratory function and exercise tolerance.126,127 Because this enzyme does not cross the blood–brain barrier, most likely it will not influence the central nervous manifestations.128

Otherwise, management revolves around supportive care. Physical therapy and nighttime splinting may prevent contractures. Special education and frequent audiologic evaluation should be instituted. Many patients benefit from hearing aids. Echocardiograms are recommended to evaluate for valvular abnormalities. Surgical interventions, including corneal transplants for cloudy corneas, cardiac valve replacement, ventriculoperitoneal shunts for communicating hydrocephalus, tracheostomies for obstructive sleep apnea, and occasionally herniorrhaphies, may be helpful. Patients may possess atlantoaxial joint instability imparting an increased risk for spinal injury and paralysis. All patients at risk should undergo careful evaluation, and spinal fusion is recommended for those who are severely affected. Prenatal diagnosis is performed by enzyme assays of cultured amniotic cells, or of cells obtained in chorionic villus sampling.129 Prenatal genetic mutational analysis is used less frequently.

I-cell disease

I-cell disease, or mucolipidosis II, is a rare autosomal recessive storage disorder due to faulty lysosomal enzyme transport. The skeletal and central nervous systems are most severely affected, but characteristic skin changes also occur. I-cell disease exhibits signs and symptoms of both mucopolysaccharidoses (particularly Hurler syndrome), and sphingolipidoses. The term I-cell, or inclusion cell, refers to the presence of cytoplasmic inclusions associated with lysosomes. Onset occurs at birth, and disease progression results in death during the first decade.

Cutaneous findings

The most notable cutaneous findings are the facial features: small orbits and prominent eyes, thickening of the eyelids with a prominent venous pattern, and fullness of the lower face with rounded cheeks. Many small telangiectasias impart a ruddy appearance to the cheeks. Patients often exhibit a fish-mouth appearance in profile as a result of prominent maxillary bones. The neck is short, and the skin has a thickened and rigid texture, particularly on the neck and ears. Gingival hypertrophy, not present in Hurler syndrome, is progressive and severe. At least one patient presented with blueberry muffin rash.130

Extracutaneous findings

Neonates commonly exhibit intrauterine growth retardation, with birthweights often below 2500 g. Linear growth is below normal and ceases at 1 year of age. Orthopedic problems manifesting as dysostosis multiplex are common presenting features. Inguinal hernias, especially in boys, may be noted at birth, and patients of both sexes have frequent upper respiratory tract infections and hepatosplenomegaly. All patients experience severe psychomotor retardation, and the majority neither walk unaided nor develop more than primitive language skills. There is progressive stiffness of all joints, first apparent in the shoulders, with decreased mobility by 2 years of age.131 The long bones of affected infants younger than 6 months display periosteal cloaking, possibly due to repeated new bone formation, and some are born with congenitally short femurs or present with findings suggestive of rickets.132 Cone-shaped phalanges and abnormalities of the skull and pelvis are also observed.133

Etiology and pathogenesis

I-cell disease is caused by mutations in the GlcNAc-phosphotransferase alpha/beta gene resulting in defective N-acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphotransferase, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of a mannose-6-phosphate marker of hydrolases normally found in lysosomes. Because newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes are not marked correctly, the mannose-6-phosphate receptor-dependent transport fails, and the enzymes are secreted out of cells instead of being targeted to lysosomes. This results in failed lysosomal degradation of macromolecules, simulating a catabolic enzyme defect.134 Fibroblast lysosomal enzymes are deficient in patients with I-cell disease, whereas the serum levels of the same enzymes are markedly elevated.135 The finding that some tissues have normal levels of lysosomal enzymes suggests that there may be an alternative method for targeting lysosomal hydrolases in these tissues.136

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of I-cell disease is suggested by detection of an increase in the activity of several hydrolases in plasma. It is confirmed by dermal fibroblast cultures, which show the characteristic cytoplasmic inclusions (I-cells) in the cultured cells. These cytoplasmic inclusions stain positively for PAS and Sudan black, but negatively for Alcian blue, suggesting that the inclusion bodies represent an abnormal accumulation of glycolipid.133 Reduced activity of lysosomal hydrolases in the fibroblasts provides additional confirmation of the diagnosis. Mutational analysis of the GlcNAc-phosphotransferase alpha/beta gene is also possible.

Differential diagnosis

I-cell disease shares most of the clinical features of Hurler syndrome, including coarse facial features, severe psychomotor retardation, and skeletal dysplasia. However, patients with I-cell disease do not exhibit mucopolysaccharides in their urine. Gingival hypertrophy and vacuolated peripheral blood lymphocytes, characteristic of I-cell disease, are not present in Hurler disease.

Treatment and course

Death in early childhood is usually secondary to pulmonary infection or congestive heart failure. Bone marrow transplantation appears to slow neurologic and cardiac progression, but does not alter the skeletal disease.137 Because of the recessive inheritance pattern, genetic counseling should be offered. Successful prenatal diagnosis has been accomplished by demonstrating elevated enzyme levels in amniotic fluid in conjunction with enzyme assays from cultured amniotic fluid cells and by electron microscopy showing marked vacuolation in chorionic villus cells.138,139

Lipoid proteinosis

Lipoid proteinosis (hyalinosis cutis et mucosae, or Urbach–Wiethe syndrome) is a rare, nonfatal, autosomal recessive disorder characterized by deposition of amorphous hyaline material around dermal blood vessels. Cutaneous lesions progress from infancy throughout childhood and become characteristic for this disease by adulthood. Even though any system can be involved, the upper aerodigestive tract, skin, and central nervous system are most commonly affected.

Cutaneous findings

The cutaneous lesions are rarely present at birth but tend to occur in the first few years of life. Initially they have varied morphologies, such as erosions, small blisters, crusts and thin papules, which may have features suggestive of impetigo, acne, or varicella. These lesions subsequently develop hypertrophic, and less often atrophic, scarring. Over time the face and trauma-prone sites develop yellowish infiltrated papules and nodules and scarring, reminiscent of cutaneous changes observed with porphyria. Scalp lesions may result in scarring alopecia and significant pruritus can be a problem in some. By about 8 years the majority of patients will display the characteristic small beaded papules along the eyelid margins (moniliform blepharosis) and lips.140 In addition to these findings, less distinctive firm papules may develop on the neck, armpits, hands, elbows, and knees. Similar lesions may involve the oral mucosa, with resultant loss of teeth and various degrees of ankyloglossia.

Extracutaneous findings

Hoarseness and a weak cry secondary to thickened vocal cords may be present at birth and are usually the first signs of the disease. Even though virtually every organ has been reported to be involved, lipoid proteinosis runs a chronic nonfatal course. Apart from the laryngeal and mucosal involvement, the central nervous system is most commonly affected, resulting in seizures or behavioral changes. Prominent corneal nerves noted with slit lamp examination and confocal microscopy are observed even before moniliform blepharosis.141 Frequently, intracranial calcifications, most often in the temporal lobes, are noted on radiographs from affected individuals.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Pathogenic loss-of-function mutations have been found in the extracellular matrix protein 1 gene (ECM1).142 The glycoprotein extracellular matrix protein 1 functions in keratinocyte differentiation, basement membrane integrity, and collagen fibril macroassembly. It is recognized also as an autoantigen target in patients with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

Routine histology of affected skin demonstrates deposition of amorphous eosinophilic, PAS-positive, hyaline-like material forming concentric rings around microvasculature of the dermis. The mucosa, especially the larynx, and internal organs may likewise be affected. Ultrastructurally, there is disruption and reduplication of the basement membrane around blood vessels and at the dermoepidermal junction. Lipoid proteinosis must first be differentiated from erythropoietic protoporphyria. Lesions in sun-protected and mucosal sites when porphyrin levels are normal assist in this distinction. Other diseases to consider in the differential include papular mucinosis, amyloidosis, cutaneous xanthomas, and leprosy. The rare finding of persistent hoarseness in infancy should be differentiated from congenital hypothyroidism, congenital dysphonia, junctional epidermolysis bullosa, and Farber lipogranulomatosis (see above).

Treatment, course, and management

There is no generally accepted treatment. Mucosal stripping of the vocal cords can temporarily relieve hoarseness, and dermabrasion and CO2 laser have been performed on skin and vocal cord lesions, respectively.143 Dimethyl sulfoxide, d-penicillamine and etretinate therapy have been attempted with varying responses.144 The overall course is generally benign, with progression throughout childhood and stabilization in early adulthood; therefore supportive care is a rational approach.

Cutaneous mucinosis of infancy

Cutaneous mucinosis (CM) is a term encompassing various disorders in which the most prominent feature is deposition of mucin in the skin. CM can be categorized as primary or secondary and diffuse or focal and include entities such as myxedema, lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis), alopecia mucinosis, cutaneous myxoid cysts, cutaneous focal mucinosis, self-healing juvenile cutaneous mucinosis, mucinous nevus and cutaneous mucinosis of infancy. All are rare and the only disorders likely to be encountered in the neonate or infant are cutaneous mucinosis of infancy (CMI) and mucinous nevus. The first case of CMI was reported by Lum in 1980. This infant developed skin lesions at 4 months of age.145 Since, there have been fewer than 10 cases of CMI reported in the English literature. Rongioletti chronicled the entire clinicopathologic spectrum from CMI to papular mucinosis within a single patient and surmised that CMI may not be a distinct disorder, but an infantile manifestation of papular mucinosis.146

Cutaneous findings

Skin lesions can be variable but the typical presentation is that of firm, skin-colored to opalescent papules on the upper arms, dorsal hands and trunk. The lesions can be symmetrical and tightly grouped, linear and in rows, or more generalized. They usually appear soon after birth but can be congenital. Histological findings of lesions demonstrate focal, well-circumscribed deposits of mucin composed of hyaluronic acid (positive stains for Alcian blue at pH 2.5 and colloidal iron) superficially located in the papillary dermis with no evidence of an increase in fibrocytes. A perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate is also seen in the superficial dermis.

Extracutaneous findings

Laboratory evaluation for paraproteinemia (elevated in scleromyxedema), thyroid function studies (abnormal in myxedema), and autoimmunity are normal or negative. There are no systemic associations typically observed with either CMI or mucinous nevus. One patient with CMI had developmental delay, congenital cataracts, inguinal hernias, and an accessory tragus of unclear etiology.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis is unknown for CMI.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

When congenital CMI needs to be distinguished from the hamartomatous mucinous nevus, it is generally a larger lesion that presents with multiple skin-colored to brownish papules and plaques in a strikingly unilateral Blaschkoid distribution. The histology differs in that there are homogeneous, band-like mucin deposits in the upper portion of the dermis.

Treatment, course, and management

The rarity of CMI precludes any acknowledged treatment recommendation. However, lesions appear to be unresponsive to high-potency topical corticosteroids or tretinoin cream.

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()