Chapter 547 Neoplasms and Adolescent Screening for Human Papilloma Virus

Ovaries

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-ovarian Abscess

Pelvic inflammatory disease complicated by a tubo-ovarian abscess should be considered in a sexually active adolescent with an adnexal mass and pain on examination (Chapter 114). These patients also typically exhibit fever with leukocytosis and cervical motion tenderness. Treatment consists of administration of intravenous antibiotics. If the lesion persists or is refractory to antibiotics, drainage of the pelvic abscess by interventional radiology should be considered.

Ovarian Carcinoma

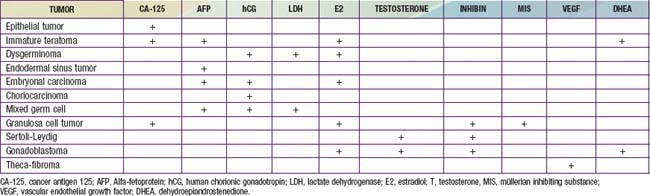

Ovarian cancer is very uncommon in children; only 2% of all ovarian cancers are diagnosed in patients <25 yr old. The SEER incidence rates are ≤0.8/100,000 at age 0-14 yr and 1.5/100,000 at ages 15-19 yr. Germ cell tumors are the most common and originate from primordial germ cells that then develop into a number of heterogeneous tumor types including dysgerminomas, malignant teratomas, endodermal sinus tumors, embryonal carcinomas, mixed cell neoplasms, and gonadoblastomas. Immature teratomas and endodermal sinus tumors are more aggressive malignancies than dysgerminomas and occur in a significantly higher proportion of younger girls (<10 yr of age). Sex-cord stromal tumors are more common among adolescents (Table 547-1). Tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and the antigen CA 125 are also used for diagnosis and treatment surveillance (Table 547-2).

| TUMOR | OVERALL 5-YR SURVIVAL | CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|

| GERM CELL TUMORS | ||

| Dysgerminoma | 85% | |

Uterus

Rhabdomyosarcomas are the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma occurring in patients <20 yr of age (Chapter 494). They can develop in any organ or tissue within the body except bone, and roughly 3% originate from the uterus or vagina. Of the various histologic subtypes, embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas in the female patient most often occur in the genital tract of infants or young children. They are rapidly growing entities that can cause the tumor to be expelled through the cervix, with subsequent complications such as uterine inversion or large cervical polyps. Irregular vaginal bleeding may be another presenting clinical symptom. They are defined histologically by the presence of mesenchymal cells of skeletal muscle in various stages of differentiation intermixed with myxoid stroma. Treatment recommendations are based on protocols coordinated by the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group and consist of a multimodal approach including surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Vincrinstine, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide with or without radiation therapy are the first line of treatment. Attitudes toward surgical management have changed dramatically, with resection rates decreasing from 100% in 1972 to 13% in 1996. Chemotherapy with restrictive surgery has enabled many patients to retain their uterus while achieving excellent long-term survival rates.

Leiomyosarcomas and leiomyomas are extremely rare, occurring in <2/10 million individuals within the pediatric/adolescent age group. However, at least 13 cases in approximately 6,200 pediatric patients with AIDS have been reported. They usually involve the spleen, lung, or gastrointestinal tract, but they could also originate from uterine smooth muscle. Pathogenesis is thought to correlate with the Epstein-Barr virus (Chapter 246). Despite treatment that demands complete surgical resection (and chemotherapy for the sarcomas), they tend to recur frequently.

Vulva

Any questionable vulvar lesion should be biopsied and submitted for histologic examination. Lipoma, liposarcoma, and malignant melanoma of the vulva have been reported in young patients. The most common lesion is likely condyloma acuminata, associated with the human papilloma virus (HPV) (Chapter 258). Diagnosis is usually made by visual inspection. Treatment consists of observation for spontaneous regression, topical trichloroacetic acid, local cryotherapy, electrocautery, excision, and laser ablation. Some products used to treat skin lesions in adults have not been approved for children, including provider application of podophyllin resin and home application of imiquimod, podophlox, and sinecatechin ointment.

Cervix

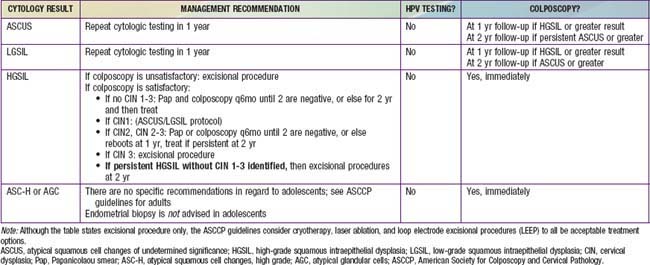

Historically, cervical cancer screening has been cytology based using the Papanicolaou (Pap) test and Bethesda Classification System (Table 547-3). Advances in epidemiologic research and molecular techniques have allowed the identification of the integral role of HPV in development of cervical cancer. HPV has become an important factor in the interpretation of cytologic results and subsequent management. The discovery of HPV presents a unique target for cervical cancer prevention, with the pediatric and adolescent population at the forefront of its implementation. A vaccine is available against the 2 HPV strains most commonly associated with cervical cancer (HPV 16, HPV 18). It is thought to be 100% effective against these 2 subtypes and to prevent up to 70% of cervical cancers. The ACOG recommends vaccination for all girls and women aged 9-26 yr, and The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/) recommends routine vaccination of girls aged 11-12 yr with 3 doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine, starting as early as 9 yr. Catch-up vaccination is indicated for girls and women aged 13-26 yr who have not been fully vaccinated. Female patients should be vaccinated even if sexually exposed; vaccination prior to exposure is ideal. Pap testing and screening for HPV DNA or HPV antibody is not required before vaccination. ACOG recommends that cervical cancer screening of women who have been immunized against HPV-16 and HPV-18 should not differ from that of nonimmunized women and should follow the exact same regimen.

The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines recommend that adolescents should be managed conservatively and should not receive Pap smear screening until age 21 yr regardless of age of onset of sexual intercourse. If an HPV test is done, the results should be ignored. However, sexually active immunocompromised (HIV positive patients or organ transplant recipients) adolescents should undergo screening twice within the first year after diagnosis and annually thereafter. Table 547-3 demonstrates management recommendations for abnormal cytologic results within the adolescent population.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 436: evaluation and management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology in adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1422-1425.

Anders JF, Powell EC. Urgency of evaluation and outcome of acute ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:532-535.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1-19.

Chow EJ, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, et al. Timing of menarche among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:854-858.

da Silva BB, Dos Santos AR, Bosco Parentes-Vieira J, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus associated with uterine inversion in an adolescent: A case report and published work review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:735-738.

da Silva KS, Kanumakala S, Grover SR, et al. Ovarian lesions in children and adolescents—an 11-year review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17:951-957.

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti–NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1091-1098.

Enriquez G, Duran C, Toran N, et al. Conservative versus surgical treatment for complex neonatal ovarian cysts: outcomes study. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:501-508.

Fallat ME, Hutter J. Preservation of fertility in pediatric and adolescent patients with cancer. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1461-e1469.

Green DM, Sklar CA, Boice JD, et al. Ovarian failure and reproductive outcomes after childhood cancer treatment: Results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2374-2381.

Gruessner SE, Omwandho CO, Dreyer T, et al. Management of stage I cervical sarcoma botryoides in childhood and adolescence. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:452-456.

Koularis CR, Penson RT. Ovarian stromal and germ cell tumors. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:126-136.

Lee SJ, Schover LR, Patridge AH, et al. American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1-14.

Orbak Z, Kantarci M, Yildirim ZK, et al. Ovarian volume and uterine length in neonatal girls. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:397-403.

Stepanian M, Cohn DE. Gynecologic malignancies n adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2004;15:549-568.

Wright TCJr, Massad S, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guideline for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

Updated Information on Cancer Statistics

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology and end results (website), http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/index.html. Accessed April 1, 2010

National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006 (website), http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/index.html. Accessed April 1, 2010

Updated Information about HPV, Cervical Cancer, and HPV Vaccine

American Cancer Society. Home page (website) http://www.cancer.org/docroot/home/index.asp Accessed April 1, 2010

American Social Health Association. HPV and Cervical Cancer Prevention Resource Center (website), http://www.ashastd.org/hpv/hpv_overview.cfm. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines and preventable diseases: HPV vaccination: human papillomavirus (HPV) (website), http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/hpv/default.htm. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer prevention and control (website), http://www.cdc.gov/cancer. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) (website), http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/. Accessed April 1, 2010

National Cancer Institute. HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines for cervical cancer (website), http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/hpv-vaccines. Accessed April 1, 2010