Chapter 6 Neoplasia

Neoplasia

Cancer is the second commonest cause of death (25%) in the Western world after heart disease. Knowledge of non-neoplastic proliferation is helpful in understanding neoplasia.

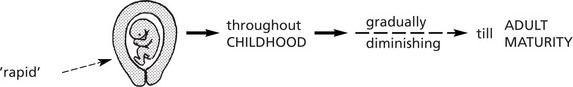

Physiological proliferation occurs:

ENLARGEMENT of an organ due to increase in the parenchymal cell mass may be due to:

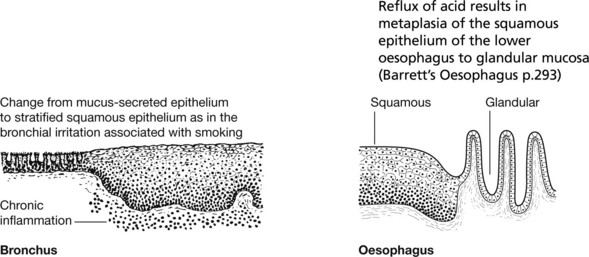

Non-Neoplastic Proliferation

Hyperplasia

Note: If the abnormal stimulus is removed, the affected organ can return to normal.

Neoplastic Proliferation

A tumour is a proliferation of cells which persists after the stimulus which initiated it has been withdrawn, i.e. it is autonomous. It is:

Neoplasms – Classification

Tumours may be classified in two ways: 1. clinical behaviour and 2. histological origin.

| BENIGN | MALIGNANT | |

|---|---|---|

| Spread (the most important feature) | Remains localised | Cells transferred via lymphatics, blood vessels, tissue planes and serous cavities to set up satellite tumours (metastases) |

| Rate of Growth | Usually slow | Usually rapid |

| Boundaries | Circumscribed, often encapsulated | Irregular, ill-defined and non-encapsulated |

| Relationship to surrounding tissues | Compresses normal tissue | Invades and destroys normal tissues |

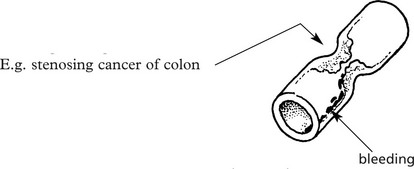

| Effects | Produced by pressure on vessels, tubes, nerves, organs, and by excess production of substances, e.g. hormones. Removal will alleviate these | Destroys structures, causes bleeding, forms strictures |

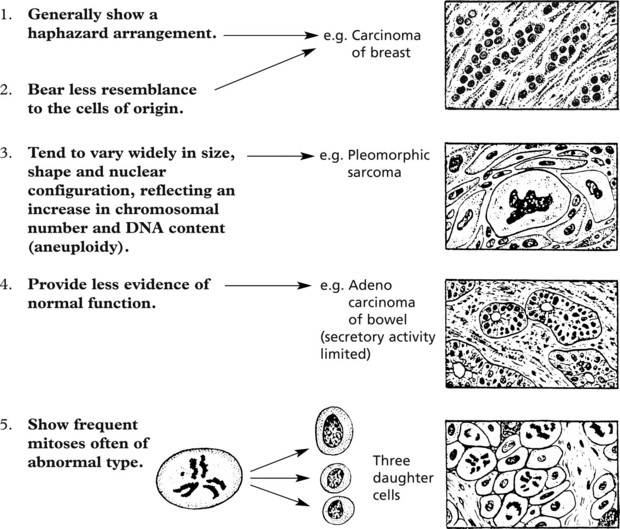

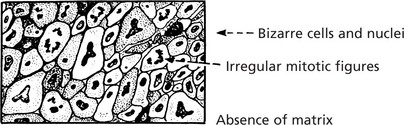

Malignant Tumours – Histology

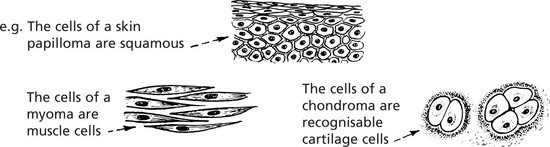

The cells of malignant tumours tend to be less well-differentiated than those of benign tumours.

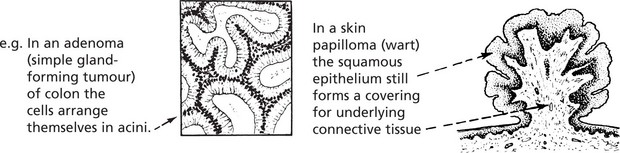

Benign Epithelial Tumours

Benign epithelial tumours are essentially of two types: 1. papillomas and 2. adenomas.

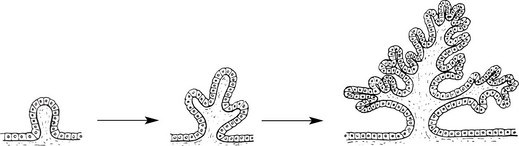

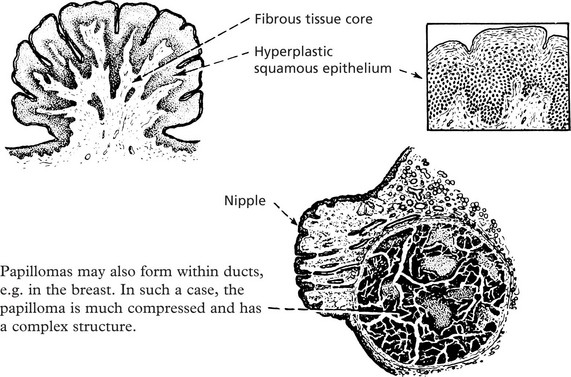

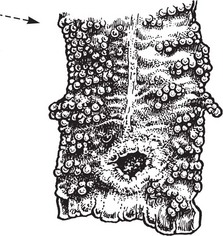

Papilloma

Typical examples are found in the skin, e.g. the common wart.

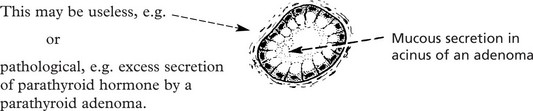

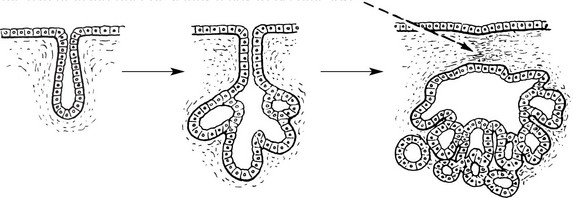

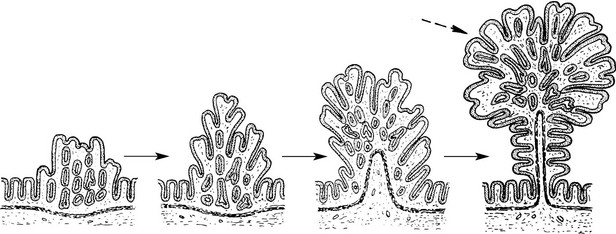

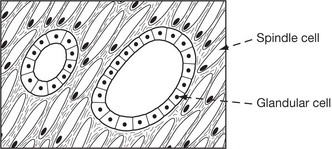

Adenoma

Adenomas are derived from the ducts and acini of glands, although the name is also used to cover simple tumours arising in solid epithelial organs.

In the type which grows into the subjacent connective tissue, the progressive budding of the epithelium results in new acini which become nipped off from the parent acini.

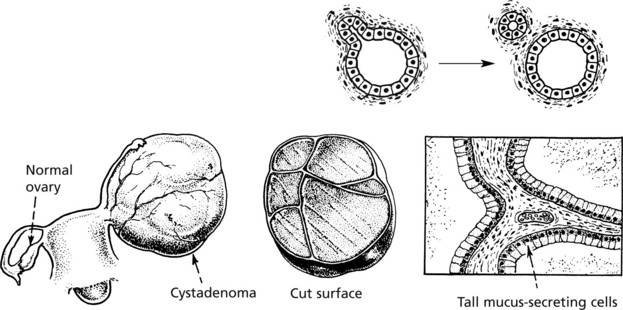

As in a hollow viscus, the proliferating epithelium may be heaped to form papillomas and the tumour then becomes a PAPILLARY CYSTADENOMA. These are also common in the ovary (see p.511).

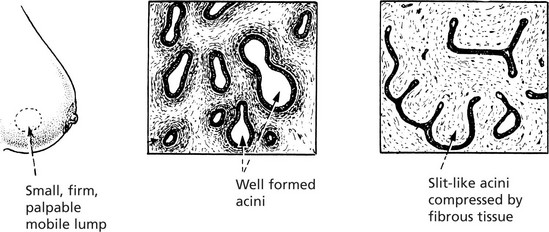

Fibroadenoma

In the breast the term is clinically useful for a small nodule consisting of a mixture of acinar elements and prominent supporting fibrous tissue. The histological appearances are variable depending on the distribution of the fibrous tissue (see also p.520). This is not now considered to be a true neoplasm.

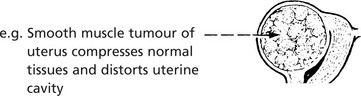

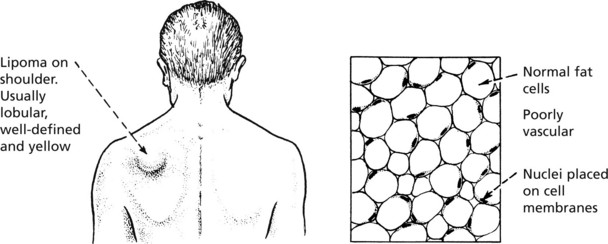

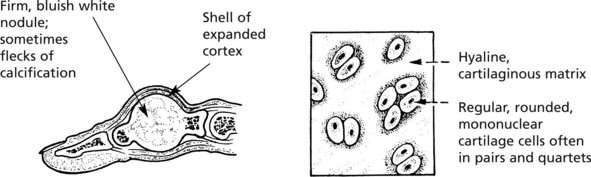

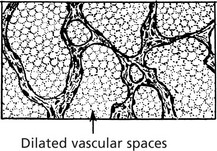

Benign Connective Tissue Tumours

Benign connective tissue tumours are composed of mature connective tissues – fat, cartilage, bone and blood vessels. They tend to form encapsulated rounded or lobulated masses which compress the surrounding tissues.

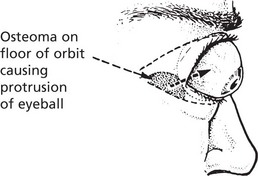

Osteoma

This tumour is mainly found in the bones of the skull, although it may occur in long bones. Osteomas are relatively small but may produce severe symptoms because of their situation.

Malignant Epithelial Tumours

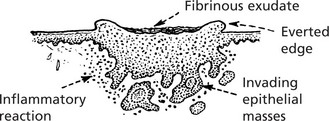

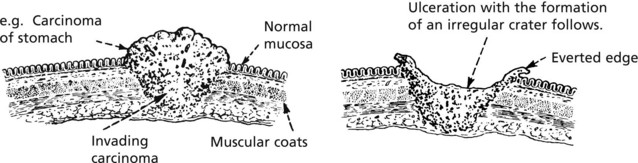

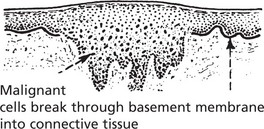

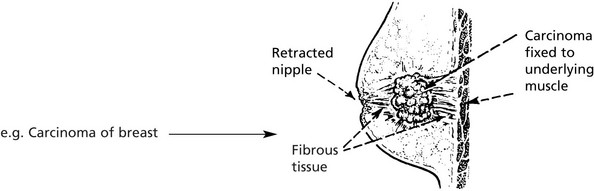

Malignant epithelial tumours are known as CARCINOMAS (Greek ‘karkinos’: a crab), referring to the typical irregular jagged shape. This is due to invasion into adjacent normal tissues (p.135).

Types of Carcinoma

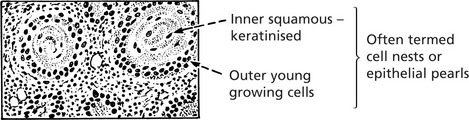

Like benign epithelial tumours, carcinomas can arise from squamous or glandular epithelium.

Types of Carcinoma

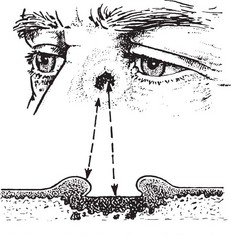

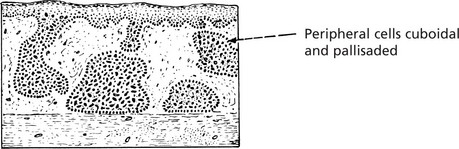

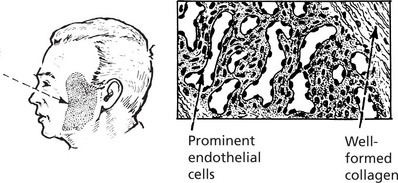

Basal Cell Carcinoma (Rodent Ulcer)

This tumour may arise in any part of the skin but is most common in the face, near the eyes and nose.

First Stage

It starts as a flattened papilloma which slowly enlarges over months or perhaps a year or two.

Carcinoma of Glandular Organs

These may take origin from gland acini, ducts or the glandular epithelium of mucous surfaces. The anatomical structure varies.

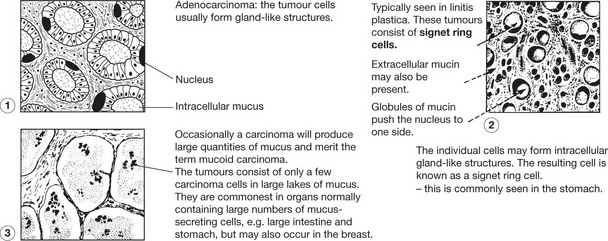

Histologically, carcinomas of glandular tissue have three basic forms.

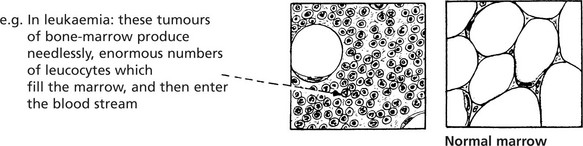

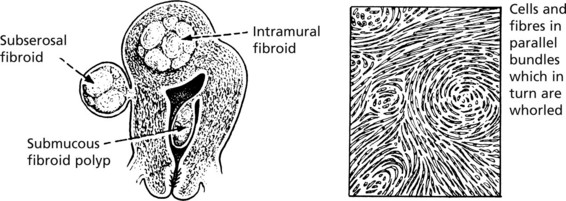

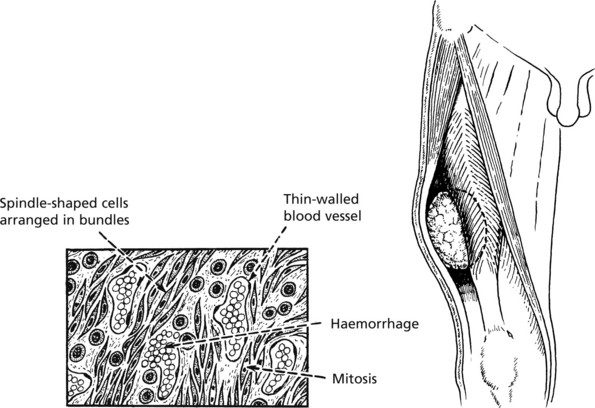

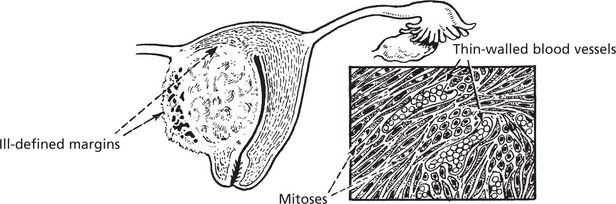

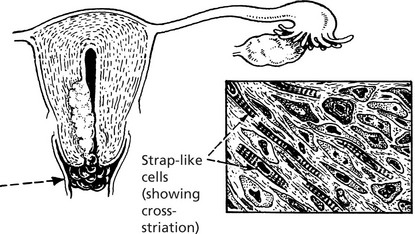

Malignant Connective Tissue Tumours

Malignant connective tissue tumours are referred to as Sarcomas (Greek ‘sarkoma’: flesh). They arise in soft tissue, in bone and rarely in viscera.

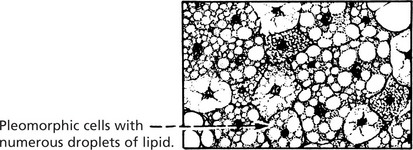

Sarcomas

Many different histological types of sarcoma have been described. The nomenclature is based on adding the suffix ‘sarcoma’ to the type of differentiation shown, e.g. chondrosarcoma, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma (cartilage, adipose tissue, smooth muscle).

Other Tumour Types

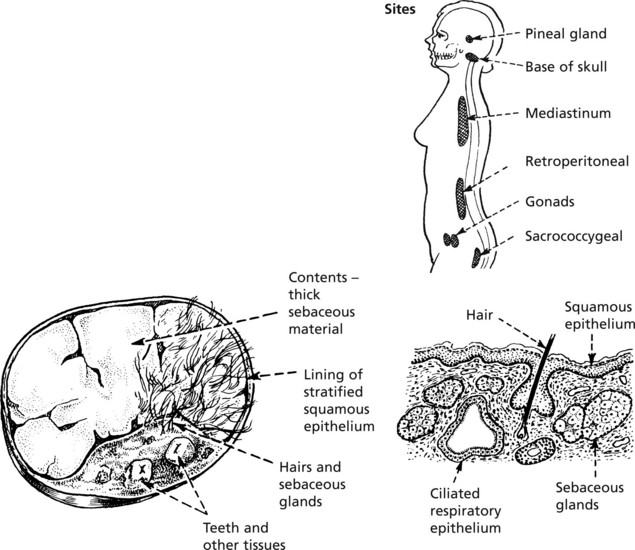

Teratoma

This is a tumour derived from totipotent germ cells. Most arise in the ovary (usually benign) and testis (almost always malignant): they may also occur at any site in the mid-line where germ cells have stopped in their migration to the gonads.

For example, Benign cystic teratoma is typically seen in the ovary.

Hamartoma

A hamartoma is a tumour-like but non-neoplastic malformation consisting of a mixture of tissues normally found at the particular site.

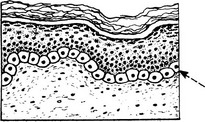

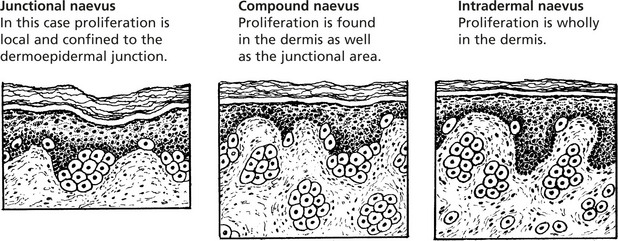

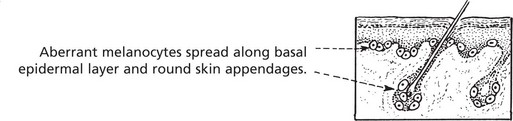

Benign Pigmented Naevus (Melanocytic Naevus or Mole)

Benign pigmented naevus is extremely common. The term ‘naevus’ means a birthmark, but most naevi are acquired in childhood and adolescence.

Blue naevus is another variation in which melanocytes are arrested in migration in the dermis.

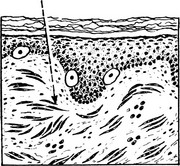

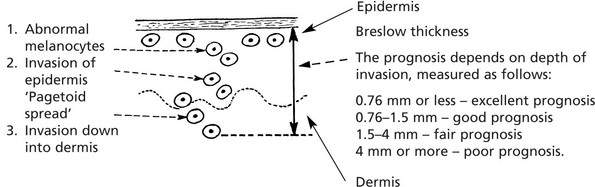

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant proliferation of melanocytes usually arises de novo but some melanomas arise from pre-existing naevi. Exposure to SUNLIGHT (the U.V. component) is the most important aetiological factor.

Sites

Some tumours are amelanotic (non-pigmented). The rate of growth is variable.

Four types of growth may occur:

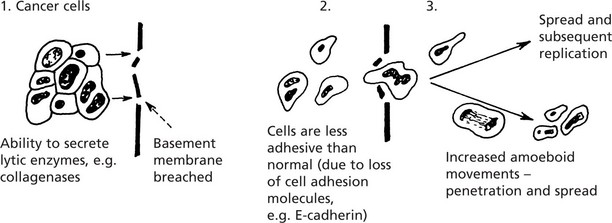

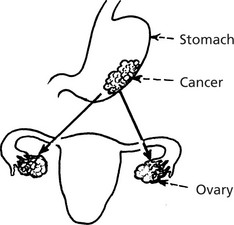

Spread of Tumours

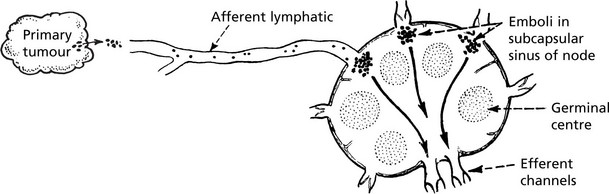

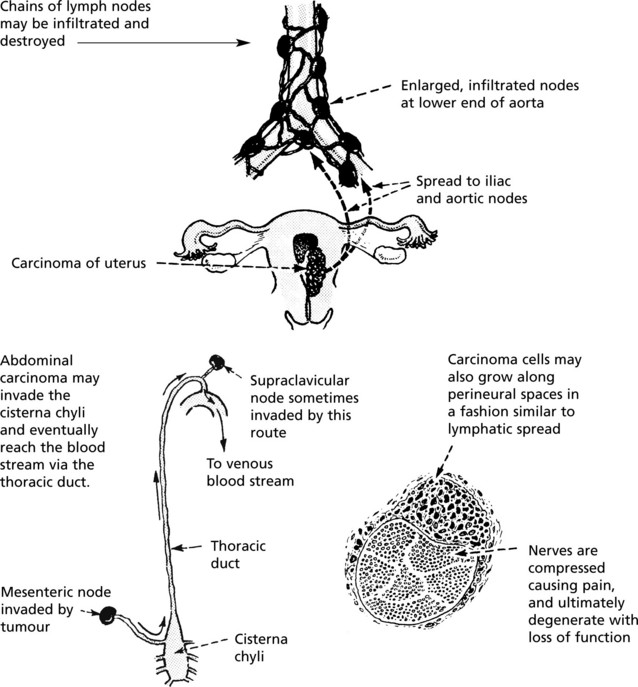

Lymphatic Spread

Lymphatic Spread

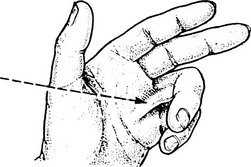

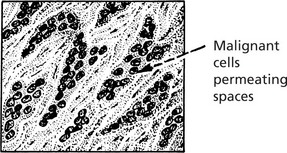

This is the commonest mode of spread of carcinomas and melanomas, but rarely of sarcomas. Malignant cells easily invade lymphatic channels from the tissue spaces.

Histological examination of the sentinel node is increasingly carried out to select the patients who require extensive lymph node dissection.

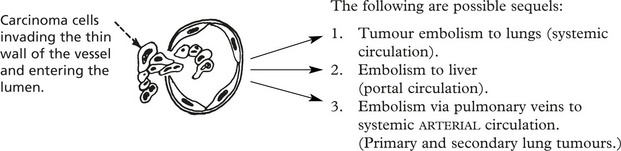

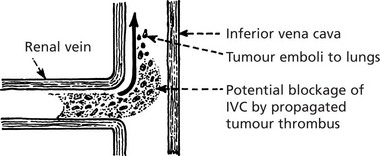

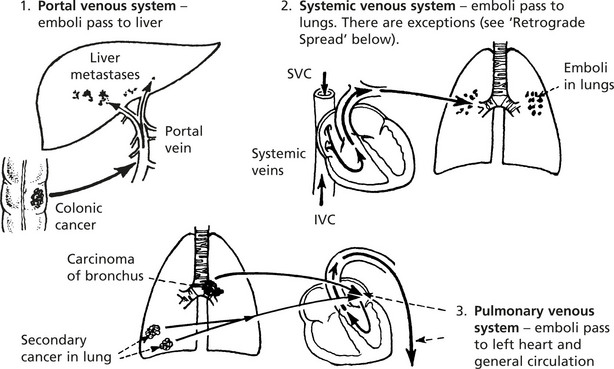

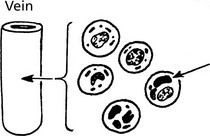

Blood Spread

Both carcinomas and sarcomas spread by the blood stream. The entry of malignant cells into the blood is via invasion of VENULES and by lymphatic embolism through the thoracic duct into the subclavian vein.

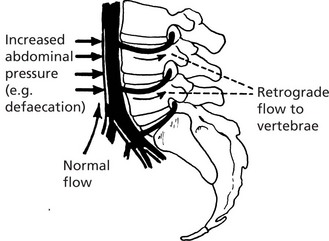

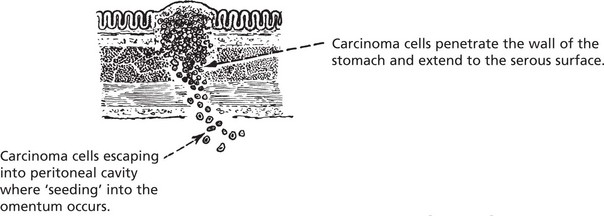

Other Modes of Spread of Tumours

Effects of Tumours

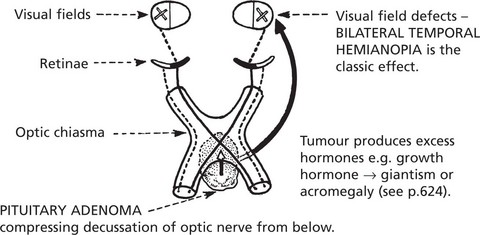

Benign Tumours

(a) The localised tumour mass may compress neighbouring structures causing loss of function and (b) benign endocrine tumours may produce excess hormones.

Malignant Tumours

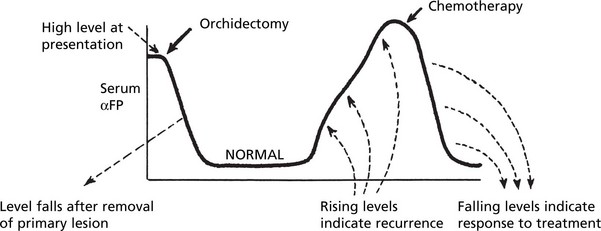

Tumour Markers

Tumour cells produce substances, many of which are proteins, which are helpful in diagnosis and monitoring of treatment.

| Tumour Marker | Tumour |

|---|---|

| Human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) | Choriocarcinoma, Teratoma of testis |

| αFeto-protein (αFP) | Hepatocellular carcinoma, Teratoma of testis |

| Prostate specific antigen, Prostatic acid phosphatase | Prostatic carcinoma |

| Carcino-embryonic antigen | Gastro-intestinal and other cancers |

| Calcitonin | Medullary thyroid carcinoma |

| 5-hydroxyindole-acetic acid (5HIAA) in URINE (metabolite of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT-SEROTONIN)) | Intestinal carcinoid |

Diagnosis of Tumours Immunocytochemistry

Diagnosis of tumours is made by combining clinical information with pathological information of several types:

Different immunocytochemical panels are used to help address specific histological dilemmas.

Thus, for a metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin, the pathologist may request:

| Cytokeratin profiling | CK 7, 19, 20 |

| Transcription factors | Wilms tumour 1 (WT1) Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) CDX2 |

| Hormone receptors | Oestogen (ER), progesterone (PR) receptors |

| ‘Tumour markers’ | Prostate specific antigen (PSA) Ca125 Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| An adenocarcinoma with this profile is likely to be of pulmonary origin | CK7 +, CK20 − TTF1 +ve, WT1 −ve, CDX2 −ve ER −ve, PR −ve Ca125 −ve PSA −ve |

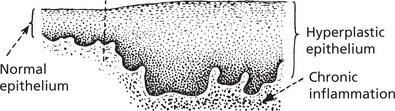

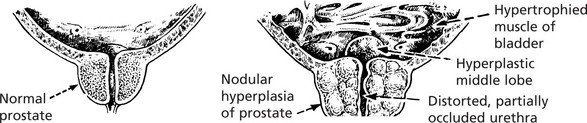

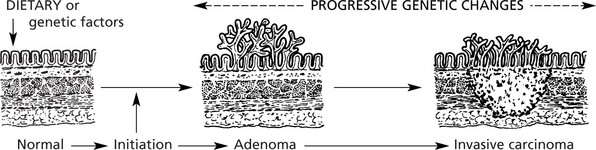

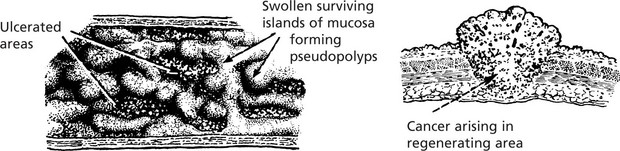

Pre-Malignancy

The pathological conditions which are associated with the development of malignancy fall into 3 groups: 1. Benign tumours, 2. Chronic inflammatory conditions and 3. Intraepithelial neoplasia.

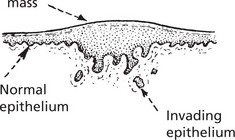

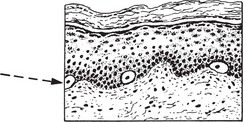

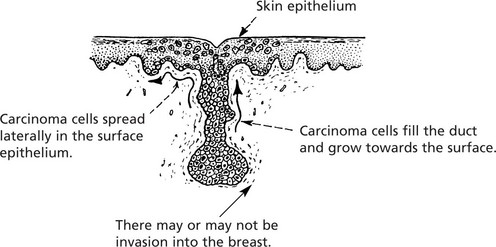

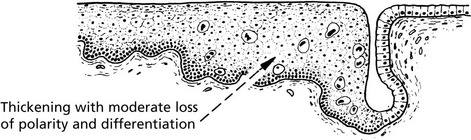

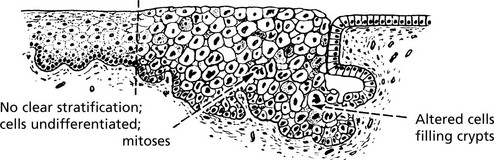

Carcinoma in situ (Intraepithelial Neoplasia)

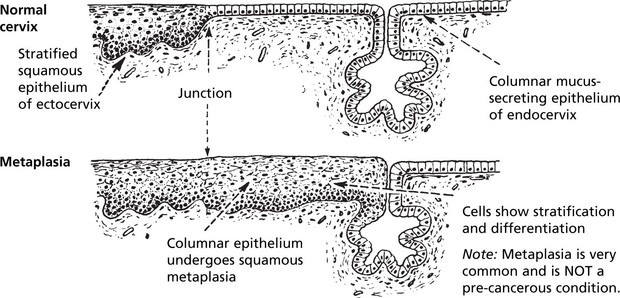

This represents an intermediate stage in the production of a cancer. All the cytological features of malignancy are present, but the cells have not invaded the surrounding tissues. It is frequently found in the cervix uteri at the junction of ecto and endocervix.

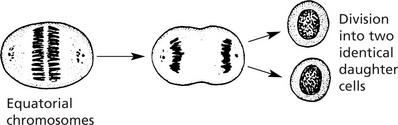

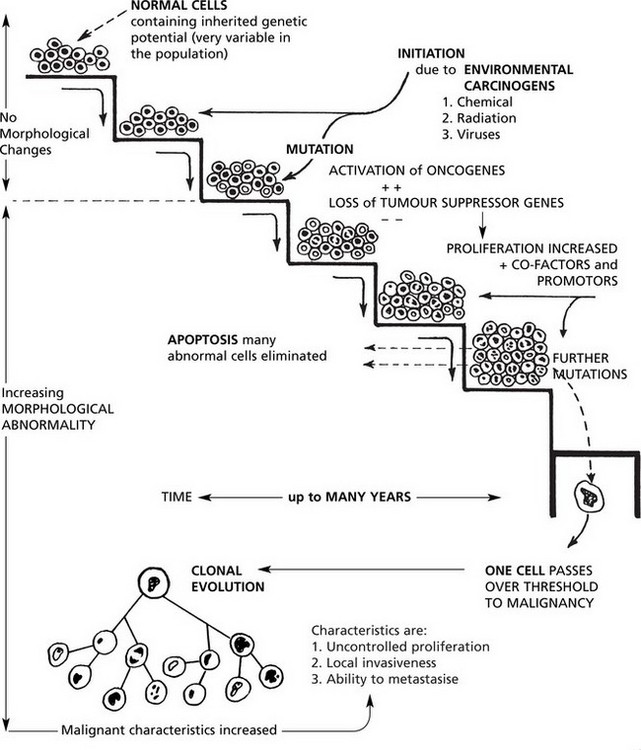

Carcinogenesis

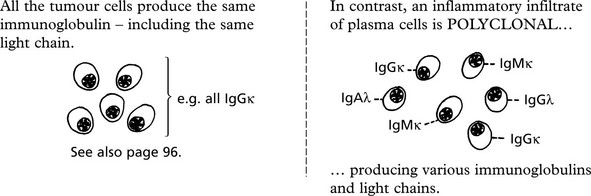

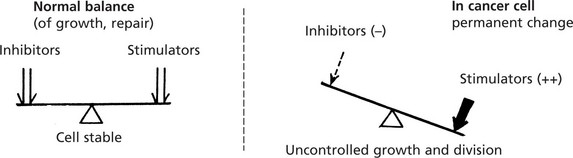

Malignant tumours are due to UNCONTROLLED PROLIFERATION of cells. Most tumours are MONOCLONAL, i.e. are derived from a single transformed cell.

This concept is well illustrated in MULTIPLE MYELOMA – a malignant tumour of plasma cells.

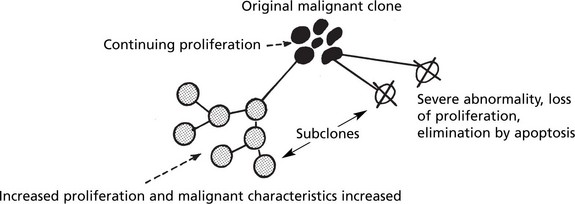

Clonal Evolution

Nuclear Morphology and DNA Content

The term ‘polyploidy’ is used when the nuclear DNA is increased by exact multiples of the normal.

‘aneuploidy’ indicates irregular increases in DNA content.→

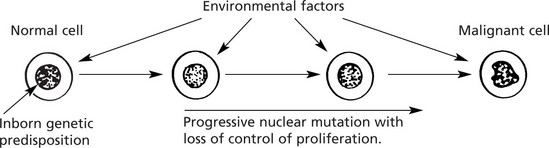

A number of factors, both environmental and genetic, contribute to a cell undergoing malignant change. This should be regarded as a multistep sequence (see p.154).

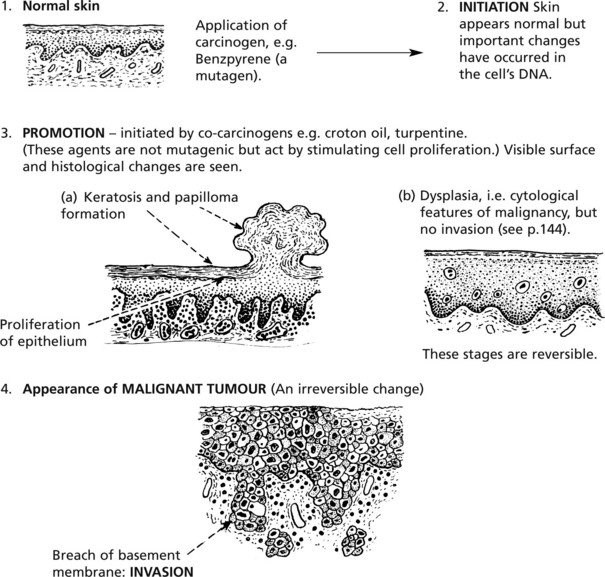

Chemical Carcinogenesis

| Industry | Tumour | Chemical Responsible |

|---|---|---|

| Aniline dyes | Bladder cancer | Naphthylamine |

| Insulation e.g. shipbuilding, building | Mesothelioma, lung, laryngeal cancer | Asbestos |

| Mineral oil and tar | Skin cancers | Benzpyrene and other hydrocarbons |

| Plastics | Angiosarcomas of liver | Vinyl chloride monomer |

| Wood dust | Cancer of nose and sinuses | ? |

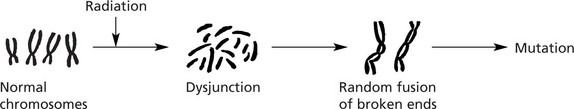

Radiant Energy

The potential dangers from irradiation give much cause for concern.

| Source of Radiation | Tumours | Type of Radiation |

|---|---|---|

| Sunlight | Melanoma, Carcinoma of skin | Ultraviolet (non-ionising) |

| Nuclear explosions (e.g. atom bombs, Chernobyl) | Leukaemia, carcinomas of lung, breast, thyroid | Ionising |

| Therapeutic irradiation | Various carcinomas, sarcomas, leukaemia | Ionising |

| Mining radioactive substances (e.g. uranium) | Lung carcinomas | Ionising |

| X-ray workers (historical) | Skin cancer, leukaemia | X-rays: Ionising |

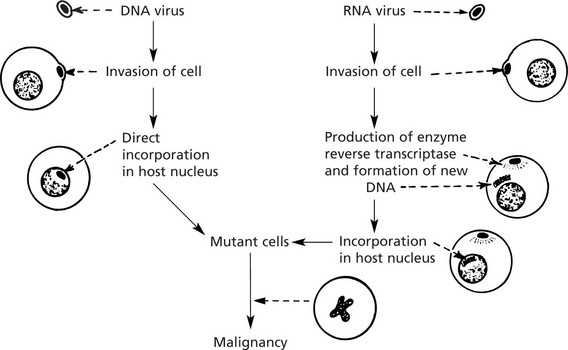

Carcinogenesis – Viruses

Viruses have long been known to cause cancer in animals (e.g. Rous sarcoma virus and the mouse mammary tumour virus – the Bittner milk factor).

In recent years viruses have been shown to contribute to the development of some human cancers.

| Virus | Type | Tumour type |

|---|---|---|

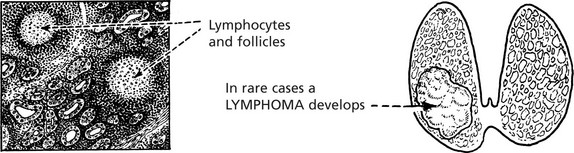

| Epstein-Barr (EBV) | DNA | Burkitt’s lymphoma, nasopharyngeal cancer, Hodgkin’s disease, post-transplantation lymphoma |

| Human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8) | DNA | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Hepatitis ‘B’ | DNA | Hepatocellular carcinomas |

| Human papilloma virus (HPV) | DNA | Cervical, penile, anal carcinoma |

| Human ‘T’ cell leukaemia virus (HTLV-1) | RNA (Retrovirus) | T-lymphoblastic leukaemia |

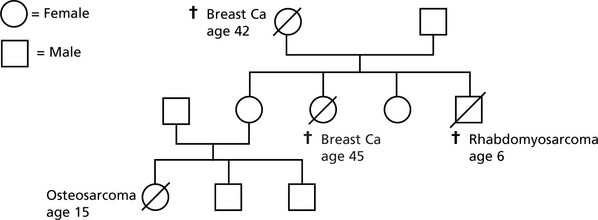

Carcinogenesis – Heredity

The inherited genetic influences in cancer are now well recognised.

Oncogenes and Tumour Suppressor Genes

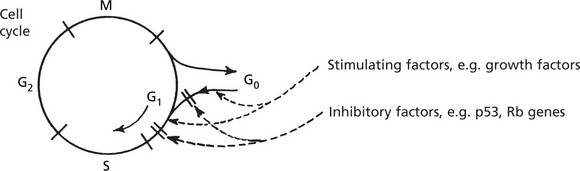

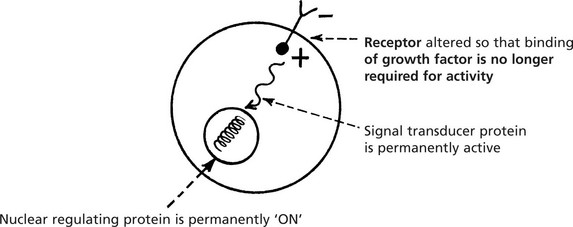

Cellular proto-oncogenes are NORMAL genes which STIMULATE cell division. Tumour suppressor genes are NORMAL genes which INHIBIT cell division. Their normal activity during somatic growth and in regeneration and repair takes place during the G0–G1 phase of the cell cycle and is strictly controlled.

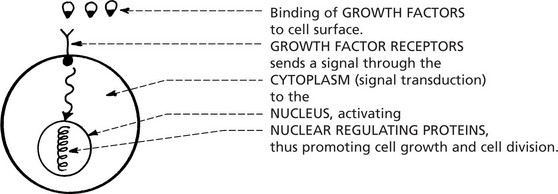

Cellular proto-oncogenes code for a number of proteins involved in cell proliferation:

Mutation or overexpression of genes which normally control apoptosis (p.4) are increasingly recognised in many tumours, e.g. overexpression of bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis in follicular lymphoma (p.432).

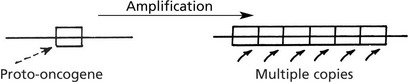

Oncogenes

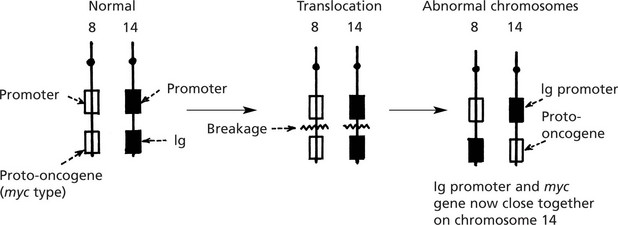

The production and activity of ONCOGENES is complex and there are many ways in which they are activated.

The myc oncogene is now under the influence of the Ig gene control and is permanently switched on.

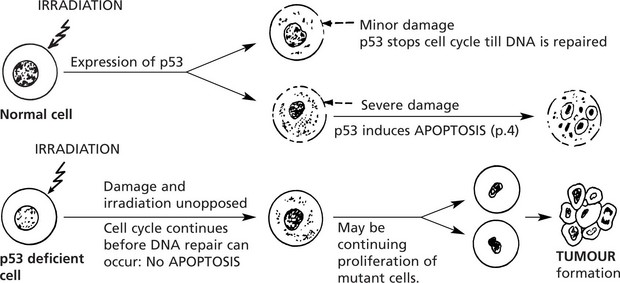

Tumour Suppressor Genes

Tumour suppressor genes are normal genes which switch off cell proliferation by acting on the cell cycle in G1. Their biological role is much broader than simply suppressing tumour function, but the name reflects how they have been discovered.

| Tumour suppressor gene | Chromosome | Tumours |

|---|---|---|

| p53 | 17 | Carcinoma of lung and breast: sarcoma |

| Retinoblastoma (Rb) | 13 | Retinoblastoma, sarcoma: some carcinomas |

| NF1 | 17 | Neurofibromas, malignant peripheral nerve tumours |

| APC | 5 | Colonic carcinoma |

| WT1 | 11 | Wilms’ tumour, bladder cancer, |

Germ line p53 mutation is a feature of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome.