Neoplasia

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of childhood, accounting for approximately 60% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 5% to 8% of all childhood cancers.1 Approximately 40% of all RMSs occur in the head and neck region. Temporal bone RMS is relatively rare. In a study of 39 pediatric head and neck RMS cases, 6 patients (15%) had temporal bone involvement.2

Most patients present before age 12 years, and 40% are younger than 5 years at presentation. An equal gender incidence is observed. The embryonal form is the most common type to involve the middle ear.3 The onset may be insidious, with presentations of serosanguineous otorrhea or nonsuppurative granulation tissue simulating otitis externa or otitis media. The most common presentation of temporal bone RMS is chronic otitis media that is not responsive to therapy.2 Many patients present with swelling or facial nerve palsy.3

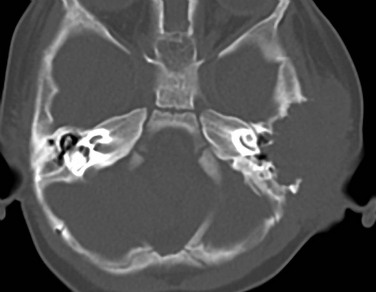

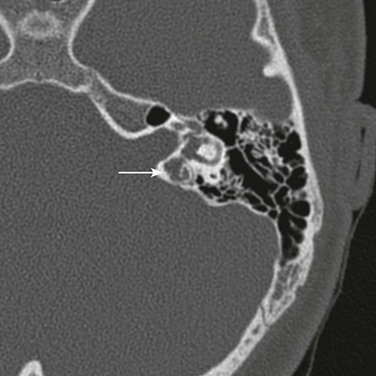

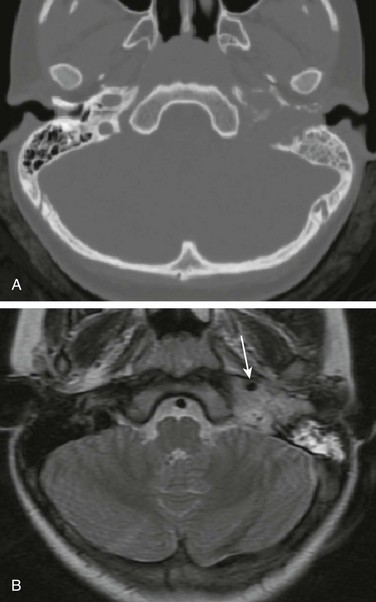

The role of computed tomography (CT) is to demonstrate bone erosion and a soft tissue mass. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated for evaluation of intracranial extension and involvement of vascular structures (internal carotid artery, jugular vein, and dural venous sinuses). MRI appearance is usually a nonspecific, enhancing, destructive mass (Fig. 12-1, A and 1B). Partial or total sparing of the otic capsule leaves the bony cochlea, vestibule, and semicircular canals isolated, creating an appearance referred to as skeletonization.

Figure 12-1 Rhabdomyosarcoma in a 12-year-old girl with hearing loss.

A, Axial noncontrast computed tomography image shows a destructive soft tissue mass involving the petrous and tympanic segments of the left temporal bone. The mastoid air cells are opacified. B, Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image displays that the mass is less hyperintense than the fluid in the mastoid air cells. The signal void of the petrous segment of the left internal carotid artery (arrow) is displaced anteriorly. (Courtesy Arzu Kovanlikaya, MD, New York.)

Treatment regimens combining chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with or without surgery, have improved the once-dismal outcomes of patients with temporal bone RMS. In a study of 14 patients, 82% of 5-year disease-free survival rate was reported.3

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a histiocytic proliferation of unknown etiology occurring primarily in infants and children. The diagnosis of LCH is made histologically by demonstration of the characteristic electron microscopic features of CD1a positivity in the involved tissue.4 In children younger than 15 years, the annual incidence of LCH is estimated to be 0.5 in 100,000.5 The mean age at presentation is 12 years, and no sex predilection is observed. The most common form of LCH is a solitary osteolytic lesion of the skull and spine.6 The temporal bone may be involved in isolation or as part of polyostotic or systemic disease.7 Temporal bone involvement may be unilateral or bilateral (30% of cases).

Although ear and temporal bone involvement is relatively rare, otologic signs and symptoms may be the only manifestations of LCH, including ear infection, otorrhea, postauricular swelling, or aural polyp. The ossicles may be eroded. Conductive hearing loss is occasionally seen in temporal bone LCH.8 Sensorineural hearing loss and vertigo may result from destruction of the bony labyrinth. The lesion is characterized on CT as a nonspecific, lytic soft tissue mass. As in calvarial LCH, no periosteal reaction of the residual bone, which has sharp, well-defined margins, is seen (Fig. 12-2). The role of MRI is to demonstrate the soft tissue mass and the associated intracranial involvement and evaluate the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, which may be concomitantly involved in systemic LCH. Chemotherapy is generally the treatment of choice for temporal bone LCH.

Lymphoma

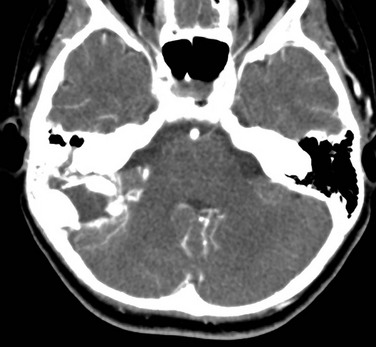

Primary lymphoma of the temporal bone is rare.9 The lesions are generally lytic and may be associated with epidural components (Fig. 12-3).

Figure 12-3 Lymphoma in a 15-year-old boy with retroauricular mass.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows a lytic, enhancing mass arising from the mastoid segment of the right temporal bone and involving the occipital bone. (From Koral K, Curran JG, Thompson A. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the temporal bone. CT findings. Clin Imaging 27:386-388.)

Endolymphatic Sac Tumor

Endolymphatic sac tumor (ELST) is a rare neoplasm arising from the epithelium of the endolymphatic sac. This adenomatous neoplasm is typically located at the posterior aspect of the temporal bone. ELST is rare in adults and even rarer in children. Patients with von Hippel–Lindau disease have an increased risk of developing ELST, particularly bilaterally.10 The characteristic imaging finding is a retrolabyrinthine mass resulting in bone erosion (Fig. 12-4). The lesions show intense enhancement with intravenous gadolinium administration. Signal voids are rarely seen on MRI despite the increased vascularity of the tumor.11 The treatment is wide surgical resection.

Osteosarcoma

Primary osteosarcoma of the temporal bone is exceedingly rare.12 The lesions can be osteoblastic, lytic, or mixed (Fig. 12-5).

Exostosis and Osteoma

Exostoses and osteomas are benign bony tumors of the external auditory canal.11 These tumors are rarely encountered in children. Exostoses generally result from prolonged exposure to cold water and are referred to as the “surfer’s ear” or “swimmer’s ear.” Osteomas are rarer than exostoses and may also arise in the middle ear, mastoid, or petrous segments of the temporal bone.

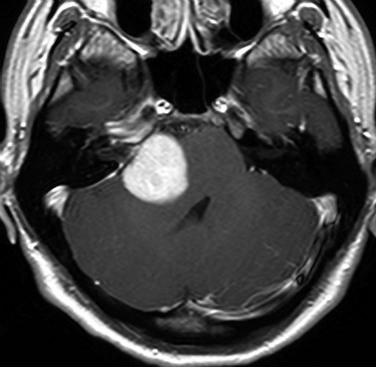

Acoustic Schwannoma (Vestibular Schwannoma)

Schwannomas are rare in children, but they are encountered in children with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). They arise from the acoustic nerve (cranial nerve VIII) more commonly than any other cranial nerve, and the vestibular division is more commonly involved than the cochlear division. Bilateral enhancing cerebellopontine angle or internal auditory canal masses are pathognomonic for NF2 (Fig. 12-6), although unilateral involvement should also be suggestive for NF2. Both the vestibular nerve and facial nerve may be involved in the cerebellopontine angle or internal auditory canal. Most lesions arise within the internal auditory canal, although a labyrinthine lesion may occur in the modiolus, cochlea, and vestibule or expand into the middle ear through the oval window. Treatment is resection, the goal being preservation of hearing.

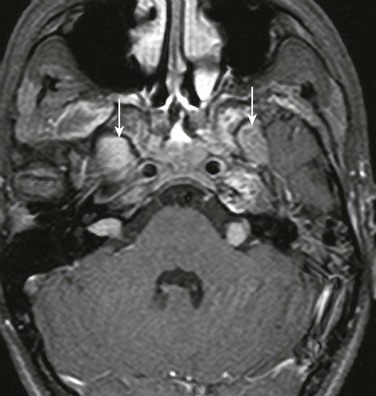

Figure 12-6 Acoustic schwannomas in a 15-year-old male with neurofibromatosis type 2.

Bilateral internal auditory canal masses are present. There are enhancing masses in the enlarged bilateral foramina ovale (arrows).

Schwannomas may be seen in other cranial nerves, including the trigeminal, facial, and chorda tympani nerves, as well as cranial nerves IX, X, and XI in the jugular foramen. Intracranial and spinal meningiomas and ependymomas may be seen in patients with NF2.13

Hemangiopericytoma

Hemangiopericytoma is a highly vascular tumor rarely seen in children.14 In the cerebellopontine angle, the main differential consideration is meningioma (Fig. 12-7). Treatment is with resection, usually followed by radiotherapy.

Paraganglioma

CT and MRI scans show a mass in the mesotympanum or jugular foramen (Fig. 12-8). These are highly vascular tumors that enhanced intensely with intravenous contrast. In larger lesions, MRI may show arborizing vessels and a typical “salt and pepper” pattern of hyperintense TI-weighted signal and hypointense T2-weighted signal. The preferred treatment is surgical excision.

References

1. Arndt, CAS. Soft tissue sarcomas. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004:1714–1717.

2. Sbeity, S, Abella, A, Arcand, P, et al. Temporal bone rhabdomyosarcoma in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(5):807–814.

3. Durve, DV, Kanegaonkar, RG, Albert, D, et al. Paediatric rhabdomyosarcoma of the ear and temporal bone. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29(1):32–37.

4. Ladisch, S. Histiocytosis syndromes of childhood. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 17th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004:1727–1730.

5. Beverley, PC, Egeler, RM, Arceci, RJ, et al. The Nikolas Symposia and histiocytosis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(6):488–494.

6. Paulus, W, Perry, A. Histiocytic tumours. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavanee WK, eds. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2007:193–196.

7. Saliba, I, Sidani, K, El Fata, F, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(6):775–786.

8. Surico, G, Muggeo, P, Muggeo, V, et al. Ear involvement in childhood Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Head Neck. 2000;22(1):42–47.

9. Koral, K, Curran, JG, Thompson, A. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the temporal bone. CT findings. Clin Imaging. 2003;27(6):386–388.

10. Janse van Rensburg, P, van der Meer, G. Magnetic resonance and computed tomography imaging of a grade IV papillary endolymphatic sac tumour. J Neurooncol. 2008;89(2):199–203.

11. De Foer, B, Kenis, C, Vercruysse, JP, et al. Imaging of temporal bone tumors. Neuroimag Clin North Am. 2009;19(3):339–366.

12. Sharma, SC, Handa, KK, Panda, N, et al. Osteogenic sarcoma of the temporal bone. Am J Otolaryngol. 1997;18(3):220–223.

13. Akeson, P, Holtas, S. Radiological investigation of neurofibromatosis type 2. Neuroradiology. 1994;36(2):107–110.

14. Tashjian, VS, Khanlou, N, Vinters, HV, et al. Hemangiopericytoma of the cerebellopontine angle: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(3):290–295.