Chapter 2 Neonatal Resuscitation

2 What preparation is necessary for the unexpected emergency department (ED) delivery?

Preparation is key, as most ED deliveries are “unexpected.” A prearranged plan should be set in motion as soon as birth is imminent. That plan should include the assembly of personnel who are best able to take care of the newly born infant. A brief history should be obtained if possible because it may affect the resuscitation. Equipment and medications specifically for a neonatal resuscitation should be kept in a designated tray so they are quickly available (Table 2-1). Periodic inspection of this equipment for proper functioning and expiration dates of medication should become part of the routine upkeep of the neonatal resuscitation tray.

Table 2-1 Equipment and Drugs for the Neonatal Resuscitation

| Equipment |

Gowns, gloves, and masks Gowns, gloves, and masks |

Warm towels and blankets Warm towels and blankets |

Bulb syringe Bulb syringe |

Meconium aspirator Meconium aspirator |

Suction catheters (sizes 5–10 Fr) Suction catheters (sizes 5–10 Fr) |

Face masks (sizes premature, newborn, and infant) Face masks (sizes premature, newborn, and infant) |

Oral airways (sizes 000, 00, 0) Oral airways (sizes 000, 00, 0) |

Anesthesia bag with manometer (preferably 500 mL, no larger than 750 mL) Anesthesia bag with manometer (preferably 500 mL, no larger than 750 mL) |

Laryngoscope with straight blades (sizes 0 and 1) Laryngoscope with straight blades (sizes 0 and 1) |

Spare bulbs and batteries Spare bulbs and batteries |

Stethoscope Stethoscope |

Endotracheal tubes (sizes 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0) and stylet Endotracheal tubes (sizes 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0) and stylet |

Tape Tape |

Umbilical catheters (3.5 and 5 Fr) Umbilical catheters (3.5 and 5 Fr) |

Oxygen source with flow meter Oxygen source with flow meter |

Umbilical catheter tray Umbilical catheter tray |

Three-way stopcocks Three-way stopcocks |

Nasogastric feeding tubes (8 and 10 Fr) Nasogastric feeding tubes (8 and 10 Fr) |

Needles and syringes Needles and syringes |

Chest tubes (8 and 10 Fr) Chest tubes (8 and 10 Fr) |

Magill forceps Magill forceps |

Radiant warmer Radiant warmer |

Cardiorespiratory monitor with electrocardiography leads Cardiorespiratory monitor with electrocardiography leads |

Pulse oximeter with neonatal probes Pulse oximeter with neonatal probes |

Suction equipment and tubing Suction equipment and tubing |

Pulse oximeter with newborn probe Pulse oximeter with newborn probe |

End-tidal CO2 detector End-tidal CO2 detector |

Laryngeal mask airway (optional) Laryngeal mask airway (optional) |

| Drugs |

Epinephrine 1:10,000 Epinephrine 1:10,000 |

Naloxone Naloxone |

Sodium bicarbonate Sodium bicarbonate |

Dextrose in water 10% Dextrose in water 10% |

Normal saline, lactated Ringer’s Normal saline, lactated Ringer’s |

Resuscitation drug chart Resuscitation drug chart |

4 What are the critical facts in the history that should be elicited, if possible, prior to delivery?

It is important to know if the expectant mother knows if she is having twins. Additional resuscitation equipment as well as personnel should be quickly gathered. Ideally there should be a resuscitation area, equipment, and personnel for each expected newly born infant.

It is important to know if the expectant mother knows if she is having twins. Additional resuscitation equipment as well as personnel should be quickly gathered. Ideally there should be a resuscitation area, equipment, and personnel for each expected newly born infant.

The expected due date is crucial to determine if the newly born infant will be premature and, if so, approximately how premature. Infants born at less than 36 weeks’ gestation are more likely to be born “unexpectedly” and will have an increased risk of needing resuscitation. Smaller-caliber equipment will be needed.

The expected due date is crucial to determine if the newly born infant will be premature and, if so, approximately how premature. Infants born at less than 36 weeks’ gestation are more likely to be born “unexpectedly” and will have an increased risk of needing resuscitation. Smaller-caliber equipment will be needed.

The color of the amniotic fluid is important. If the fluid is meconium stained (greenish), then one should anticipate a distressed newly born infant with or without airway obstruction from the meconium. The infant may require intubation with suctioning. Equipment should be available and personnel should be aware of this clinical situation.

The color of the amniotic fluid is important. If the fluid is meconium stained (greenish), then one should anticipate a distressed newly born infant with or without airway obstruction from the meconium. The infant may require intubation with suctioning. Equipment should be available and personnel should be aware of this clinical situation.

7 How do you assess the condition of a newly born infant?

The basic principles for the newly born infant are the same as for any patient. However, there are particular problems of the neonate that bear special attention. After placing the neonate under the prewarmed radiant warmer on his or her back, dry and suction the baby (see Question 5). Carefully observe the respiratory effort and rate. If cyanosis or other signs of distress are noticed, administer oxygen. If the respiratory response is inadequate, stimulate the infant again and reposition. Adequacy of respirations is based on the rate (usually 35–60 breaths per minute), the effort (lack of retractions and grunting), and breath sounds. If the respiratory effort continues to be suboptimal (absent, slow, shallow), begin positive-pressure ventilation. If the respiratory effort is adequate, then evaluate the heart rate.

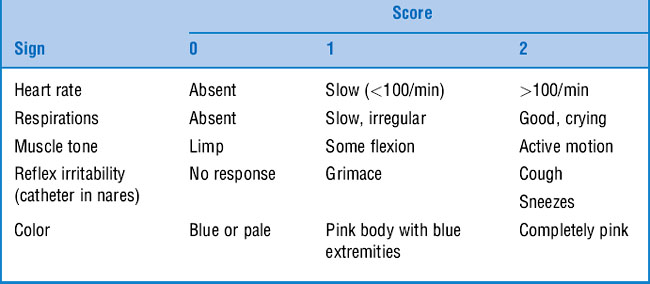

Finally, assign an Apgar score at 1 minute and at 5 minutes of life (Table 2-2). The Apgar score assesses heart rate, respirations, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color. It indicates how the infant is doing or the responsiveness to the resuscitation. If the Apgar score is less than 7 at 5 minutes, continue scoring every 5 minutes. Do not delay resuscitative efforts to obtain an Apgar score.

10 What are the indications for tracheal intubation of the newly born infant?

11 How should endotracheal intubation of the newborn be performed?

13 What is the proper technique for chest compressions in the newborn?

David R: Closed chest cardiac massage in the newborn infant. Pediatrics 81:552–554, 1988.

14 How does the resuscitation of the newly born infant differ if meconium is present in the amniotic fluid?

15 What are the most common drugs used in a neonatal resuscitation, and when are they indicated?

Epinephrine is recommended when the heart rate remains below 60 beats per minute despite adequate ventilation with 100% oxygen and chest compressions for 30 seconds. Evidence from neonatal models shows increased diastolic and mean arterial pressures in response to epinephrine. The current recommended dose for epinephrine during the neonatal resuscitation is 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg of 1:10,000 concentration (0.1–0.3 mL/kg). High-dose epinephrine is not recommended for neonates because of the rare incidence of ventricular fibrillation and the theoretical risk of a hypertensive response, which could result in intraventricular hemorrhage.

Epinephrine is recommended when the heart rate remains below 60 beats per minute despite adequate ventilation with 100% oxygen and chest compressions for 30 seconds. Evidence from neonatal models shows increased diastolic and mean arterial pressures in response to epinephrine. The current recommended dose for epinephrine during the neonatal resuscitation is 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg of 1:10,000 concentration (0.1–0.3 mL/kg). High-dose epinephrine is not recommended for neonates because of the rare incidence of ventricular fibrillation and the theoretical risk of a hypertensive response, which could result in intraventricular hemorrhage.

Atropine is a parasympathetic drug that decreases vagal tone and is not recommended in neonatal resuscitation. Bradycardia in the neonate is usually caused by hypoxia, and therefore atropine is unlikely to be beneficial.

Atropine is a parasympathetic drug that decreases vagal tone and is not recommended in neonatal resuscitation. Bradycardia in the neonate is usually caused by hypoxia, and therefore atropine is unlikely to be beneficial.

Naloxone is a narcotic antagonist that is indicated in the newborn with respiratory depression thought to be secondary to drugs given to the mother during delivery. The dose of naloxone is 0.1 mg/kg, delivered through the IV or IM route. Because of the short half-life relative to most narcotics, repeat doses may be required, and careful observation of the neonate after administration is necessary. Do not give naloxone to infants of mothers who have recently abused narcotics because it will precipitate an acute withdrawal syndrome in the newborn. Endotracheal administration of naloxone to newborns is not recommended because of lack of clinical data.

Naloxone is a narcotic antagonist that is indicated in the newborn with respiratory depression thought to be secondary to drugs given to the mother during delivery. The dose of naloxone is 0.1 mg/kg, delivered through the IV or IM route. Because of the short half-life relative to most narcotics, repeat doses may be required, and careful observation of the neonate after administration is necessary. Do not give naloxone to infants of mothers who have recently abused narcotics because it will precipitate an acute withdrawal syndrome in the newborn. Endotracheal administration of naloxone to newborns is not recommended because of lack of clinical data.

Sodium bicarbonate helps to reverse systemic acidosis and is indicated in neonatal resuscitation after adequate ventilation is established and metabolic acidosis is suspected. If adequate ventilation is not established, the metabolic acidosis will be replaced by respiratory acidosis. Other complications from bicarbonate include hypernatremia and intraventricular hemorrhage. The recommended dose of sodium bicarbonate is 1 to 2 mEq/kg in a dilute solution of 0.5 mEq/mL given slowly at 1 mEq/kg/min.

Sodium bicarbonate helps to reverse systemic acidosis and is indicated in neonatal resuscitation after adequate ventilation is established and metabolic acidosis is suspected. If adequate ventilation is not established, the metabolic acidosis will be replaced by respiratory acidosis. Other complications from bicarbonate include hypernatremia and intraventricular hemorrhage. The recommended dose of sodium bicarbonate is 1 to 2 mEq/kg in a dilute solution of 0.5 mEq/mL given slowly at 1 mEq/kg/min.

Volume expanders such as crystalloids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s) and colloids (blood) are indicated for signs of hypovolemia. Signs of hypovolemia in the neonate include pallor, weak pulses, or poor response to resuscitative efforts. The dose for volume expanders is 10 mL/kg, with reassessment after each dose. Isotonic crystalloids are the first choice in volume expanders. Red blood cells (O negative) are indicated in situations of large blood loss. Albumin is less frequently used because of limited availability, risk of infection, and an association with increased mortality.

Volume expanders such as crystalloids (normal saline or lactated Ringer’s) and colloids (blood) are indicated for signs of hypovolemia. Signs of hypovolemia in the neonate include pallor, weak pulses, or poor response to resuscitative efforts. The dose for volume expanders is 10 mL/kg, with reassessment after each dose. Isotonic crystalloids are the first choice in volume expanders. Red blood cells (O negative) are indicated in situations of large blood loss. Albumin is less frequently used because of limited availability, risk of infection, and an association with increased mortality.

16 Where is the best place to obtain IV access?

1 Prevent hypothermia. Although some studies have suggested that cerebral hypothermia of the asphyxiated infant may protect against brain injury, it is not routinely recommended pending controlled human studies.

2 Prevent hyperthermia because it has been associated with perinatal respiratory depression.

3 Use 100% oxygen with positive-pressure ventilation. Although some studies have shown that lower inspired oxygen is useful in some settings, this is not recommended because of insufficient data.

4 A laryngeal mask may be used as an alternative airway method by trained providers when bag-mask ventilation is ineffective or attempts at endotracheal intubation have been unsuccessful.

5 Confirm endotracheal intubation with CO2 detectors.

6 The two-thumb method of chest compressions is preferred for newborns, with the depth of compression being one-third of the anterior–posterior diameter of the chest rather than a fixed depth. Compression should be deep enough to generate a pulse.

7 Administer epinephrine if the heart rate remains 60 beats per minute after 30 seconds of adequate ventilation and chest compressions.

8 Albumin-containing solutions are no longer the fluid of choice for initial volume expansion. Isotonic crystalloids are the first choice.

9 Intraosseous access can be used if the umbilical vein is not readily available.