11 Needle Imaging

Needle tip visibility is critical to the success and safety of regional block interventions. It is imperative to identify the needle tip before advancing the needle. The cut on the bevel is the best identifier of the needle tip for a beveled needle. Partial lineups (so that the needle tip is not within the plane of imaging but some of the needle shaft is) are a source of false reassurance with in-plane technique. A number of factors have been reported to influence needle tip visualization under clinical imaging conditions (Table 11-1).

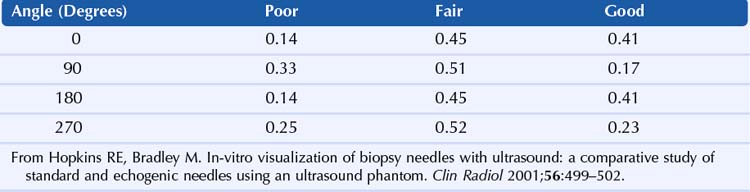

Table 11-1 Factors Reported to Influence Needle Tip Visibility

Insertion Angle (Angle of Insonation)

Needle tip imaging is optimal when the needle is parallel to the active face of the transducer. The cleanest needle echo is from a conventional needle at or near parallel. One study found a linear correlation between angle of incidence (measured from 0-75 degrees) and the mean needle tip brightness.1

Needle Gauge

There are multiple advantages to using a large needle for regional block. Needles as large as 17 gauge have been used to improve needle tip visibility for regional blocks.2 Alignment of a large needle is faster with in-plane technique. An additional advantage of a large needle is the ability to redirect the needle within the scan plane. A large needle tip can be used to displace structures (e.g., arteries or nerves) before advancing. The disadvantages of the large needle are patient discomfort and the consequences of unintended puncture (e.g., of vessels, nerves), which are typically worse. In addition, the soft tissue properties (tent and recoil) are more noticeable with large needles. With finer needle tips, the hand motion and needle tip motion are more closely matched, and it is easier to place a fine needle tip within a thin fascial plane.

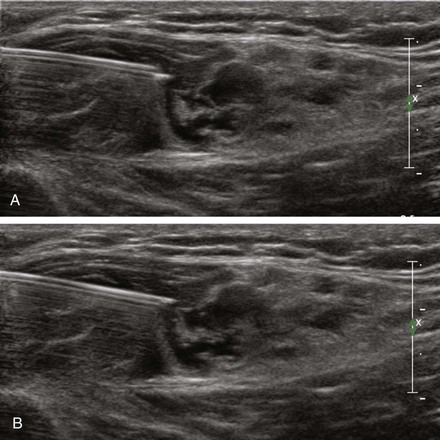

Bevel Orientation

Needle bevel orientation is important for needle tip visibility (Table 11-2).3 The bevel should be facing the transducer to enhance needle tip imaging.

Needle Motion and Test Injections

Some clinicians move the needle slightly or use small-volume test injections (<1 mL) to improve the needle tip visibility.4 Because regional anesthesia interventions are performed near reactive structures, if needle motion is used, it should be small and slow (avoid rapid jabbing motions, which may cause puncture or paresthesia).

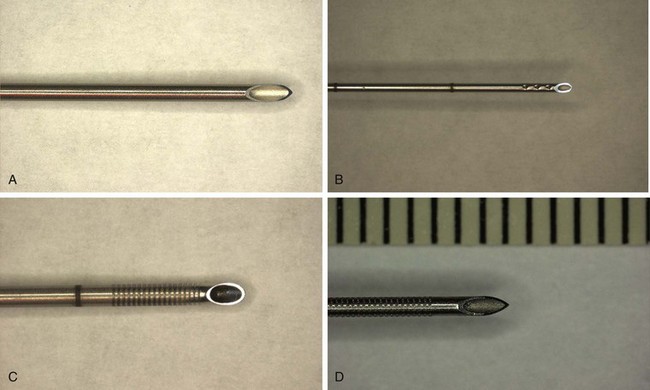

Echogenic Modifications

McGahan roughened up the surface of needles with a No. 11 surgical blade to improve the needle tip visibility.5 Historically, this was one of the first echogenic needle designs. When the angle of approach is more the 30 degrees, an echogenic needle is of benefit because the roughened surface sends echoes back to the transducer.6

Spatial Compound Imaging

With an increasing angle of incidence, the decrease in needle visibility is more pronounced for single-line ultrasound than for compound imaging. However, at angles of incidence of more than 30 degrees, the needle was barely visible with either method of imaging.7

Clinical Pearls

• Among specialized needles used for regional blocks, Hustead needle tips tend to have better ultrasound visibility.

• Side-port needles for regional block do not appear to exhibit isotropic diffraction, which has been reported to enhance the ultrasound visibility of similar needles.8

• Large-bore needles can be used as nerve retractors, pushing or pulling nerves out of the way of the advancing needle.

• Bevel orientation should be toward the nerve (so that the needle will pass the nerve rather than puncture it).

• When navigating the block needle between two nerves, the bevel should be rotated to face the closer of the two. This helps the block needle shoot the intervening gap and makes the closer nerve roll to the side as the needle is advanced. The same bevel orientation strategy can be used when placing the block needle between a nerve and an artery.

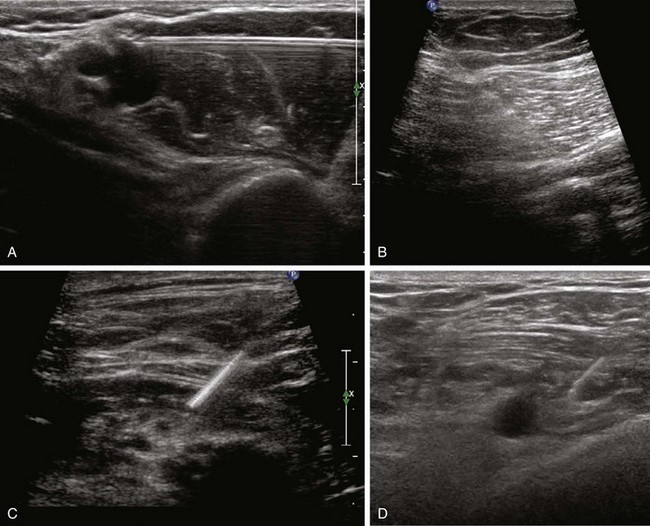

FIGURE 11-2 Influence of bevel orientation on needle tip visibility: bevel up (A) and bevel down (B).

1 Bondestam S, Kreula J. Needle tip echogenicity: a study with real-time ultrasound. Invest Radiol. 1989;24:555–560.

2 Sandhu NS, Capan LM. Ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:254–259.

3 Hopkins RE, Bradley M. In-vitro visualization of biopsy needles with ultrasound: a comparative study of standard and echogenic needles using an ultrasound phantom. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:499–502.

4 Feller-Kopman D. Ultrasound-guided internal jugular access: a proposed standardized approach and implications for training and practice. Chest. 2007;132:302–309.

5 McGahan JP. Laboratory assessment of ultrasonic needle and catheter visualization. J Ultrasound Med. 1986;5:373–377.

6 Deam RK, Kluger R, Barrington MJ, et al. Investigation of a new echogenic needle for use with ultrasound peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:582–586.

7 Cohnen M, Saleh A, Luthen R, et al. Improvement of sonographic needle visibility in cirrhotic livers during transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedures with use of real-time compound imaging. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:103–106.

8 Hurwitz SR, Nageotte MP. Amniocentesis needle with improved sonographic visibility. Radiology. 1989;171:576–577.