Chapter 32 NECK MASSES

Key Physical Findings

Quantification of the size of the lesion

Quantification of the size of the lesion

Location or anatomical site of the lesion (posterior triangle, supraclavicular)

Location or anatomical site of the lesion (posterior triangle, supraclavicular)

Mobility or fixation to internal structures

Mobility or fixation to internal structures

Table 32-1 characterizes key examination findings of common lesions.

| Diagnosis | Location | Physical Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Branchial cleft cyst | Anterior to middle third of sternocleidomastoid muscle | Mass that may retract with swallowing. Fistula may or may not be present. |

| Cat-scratch disease | Anterior triangle, submandibular, or preauricular | Tender lymphadenopathy |

| Cystic hygroma (lymphangioma) | Anterior triangle, submandibular, or preauricular | Soft spongy mass, nontender. May increase in size with Valsalva maneuver. Can be differentiated from hemangioma in that it transilluminates. |

| Dermoid cyst | Midline lesions | Mobile, painless, firm mass. Does not move with tongue protrusion. |

| Hemangioma | May occur at various locations on neck and face | Soft mobile mass that increases in size with Valsalva maneuver. Red/bluish. Does not transilluminate. |

| Lymphadenitis | Multiple inflamed masses in the anterior and posterior triangle | Painful, erythematous, fluctuant nodes. Patient may have fever; may drain purulent fluid. |

| Lymphoma | Occipital and supraclavicular | Large, firm, usually painless mass |

| Mycobacterial and granulomatous infections | Cervical, submandibular, supraclavicular | Painful, may be erythematous, may have draining sinus tract |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Parameningeal sites (posterior aspect of neck), multiple locations | Painless, rapidly enlarging mass |

| Thyroglossal duct cyst | Anterior neck, submental and midline | Firm mass that retracts with tongue protrusion |

Suggested Work-up

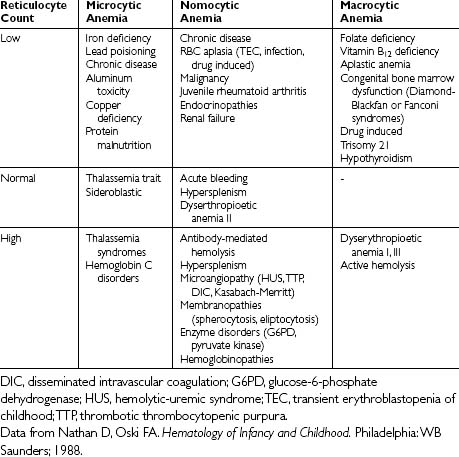

| Complete blood count (CBC) | If an infection or malignant process is suspected |

| Purified protein derivative (PPD) tuberculin test | If mycobacterial infection is suspected. The test will be negative in 50% of cases of atypical mycobacterial infection. |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein | May be useful in characterizing the neck mass as part of a systemic illness |

| Chest radiograph | If malignancy or mycobacterial infection is suspected |

| Ultrasonography | To distinguish between a cystic lesion and a solid mass. Helpful in differentiating congenital cystic masses from solid lymph nodes and neoplasms. |

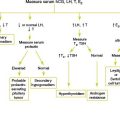

| Fine needle aspiration or open biopsy | May be required to establish the diagnosis, especially when other diagnostic tests are unrevealing and the mass persists or increases in size. See Table 32-2. |

Table 32-2 Criteria for Cervical Lymph Node Biopsy*

* When other diagnostic tests are unrevealing, biopsy may be required to rule out malignancy and establish the diagnosis.

Additional Work-up

| Serologic studies | If toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus infection, or Epstein-Barr virus infection is suspected |

| Bartonella henselae antibody | If cat-scratch disease is suspected |

| Wound cultures | Useful in cases of suppurative lymphadenitis to identify a pathogen and choose an appropriate antibiotic |

| Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies | If a rheumatologic process is suspected |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan | More effective than ultrasonography in identifying deeper, less well-defined lesions |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of neck masses | Becoming more widely used early in the evaluation |

| Thyroid scan and/or thyroid function tests | If thyroglossal duct cyst is suspected |

| Sialography | If sialadenitis is suspected |

| Arteriography | May be helpful in evaluating hemangioma |

1. Brown R.L., Azizkhan R.G. Pediatric head and neck lesions. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:889–905.

2. Jordan N., Tyrell J. Management of enlarged cervical lymph nodes. Curr Paediatr. 2004;14:154–159.

3. Kelly C.S., Kelly R.E. Lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:875–888.

4. Park Y.W. Evaluation of neck masses in children. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1904–1911.

5. Zitelli B.J. Evaluating the child with a neck mass. Contemp Pediatr. 1990;7:90–112.