CHAPTER 121 Neck Dissection

Historical Perspective

In publications that came out before the 20th century, little attention was given to the indications or techniques for treating cervical lymph node metastases. The first conceptual approach for removing nodal metastases was made by Kocher in 18801; he described the removal of the lymph nodes located within the contents of the submandibular triangle to gain surgical access to a cancer of the tongue. Later, Kocher recommended that nodal metastases should be removed more widely through a Y-shaped incision, with the long arm extending from the mastoid to the level of the omohyoid at its junction with the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Around the same time, Packard supported the concept of removing the surrounding lymph nodes for lingual cancer.2 The first description of the radical neck dissection was by Jawdynski, a Polish surgeon.3 However, the individual credited the most for developing and reporting the efficacy of this procedure is George Crile.4 Crile believed that distant (hematogenous) metastases were uncommon in head and neck cancer and that metastases more commonly occurred in the neck through the permeation of lymphatics. The descriptions by both of these surgeons of a block resection encompassing all of the cervical nodal groups from the level of the mandible above to the clavicle below became the basis for the radical neck dissection we know today. Relevant to the modifications of radical neck dissection that were subsequently made, Crile recommended preservation of the internal jugular vein and the sternocleidomastoid muscle for patients in whom there were no palpable nodes. In addition, his technique was to remove only the regional lymph nodes that were known to drain the field of the original focus of disease when metastases could not be seen. Also, it is interesting to note that, in the accompanying illustrations of the more radical en bloc resections, the spinal accessory nerve was preserved.

This philosophy of radical en bloc resection based on Crile’s descriptions remained popular with the head and neck surgeons during the first half of the 20th century, in part because of the works of Blair and Brown5 and Martin,6 who were strong proponents of the radical en bloc technique of neck dissection in a manner similar to the radical surgery that had evolved for breast cancer. Martin, in particular, categorically insisted that the spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein, and sternocleidomastoid muscle should be removed as part of all cervical lymphadenectomies. It may be useful to remember that, during this time, radiotherapy had not yet been developed as an effective adjuvant modality, and radical surgery represented the only hope for cure.

Associated with the procedure of the radical neck dissection was the presence of significant postoperative morbidity related to shoulder dysfunction; the operation also had limitations as a bilateral procedure.7 In the 1950s Ward and Robben8 reported that the neck dissection could be modified in some circumstances by sparing the spinal accessory nerve and thereby preventing postoperative shoulder drop. Later, Saunders, Hirata, and Jaques9 compared the functional results of cases undergoing radical neck dissection with those in whom the spinal accessory nerve was spared; this demonstrated that shoulder symptoms were only mild or moderate in more than 80% of the patients who had the nerve preserved or cable grafted. The concept of conservation neck surgery was further popularized during the 1960s by Suarez10 in Argentina and promoted by Bocca and Pignataro,11 who independently described an operation that removed all of the lymph node groups while sparing the spinal accessory nerve, sternocleidomastoid muscle, and internal jugular vein. They emphasized that fascial compartments surrounding the lymphatic contents of the neck could be removed without sacrificing the nonlymphatic structures, as mentioned.

Other authors reported the sparsity of nodal disease within the posterior triangle for carcinoma of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx, thus setting the stage for modifications directed toward preserving lymph node groups.12–15 These observations paved the way for another type of neck dissection modification: one in which there was selective preservation of one or more lymph node groups.16–18 Some of the initial proponents of this concept were the surgeons at MD Anderson Cancer Center, who called the procedure “modified neck dissection.”19,20 Two of the variations of the modified neck dissection were also called “supraomohyoid” and “anterior” neck dissections.16 However, the term selective neck dissection (SND) subsequently became associated with the concept of preserving lymph nodes in one or more of the neck levels through the American Academy of Otolaryngology’s classification.17,21 The lymph node groups removed are based on the pattern of metastases, which are predictable relative to the primary site of cancer.

Terminology of Neck Dissection

The evolution of cervical lymphadenectomy procedures during the 20th century has provided the modern head and neck surgeon with a repertoire of surgical techniques for removing nodal metastases. Concurrent with this expansion has been the emergence of a multitude of terms used to describe these procedures. Originally proposed by authors without any uniformity of terminology, this lack of standardization unfortunately resulted in redundancy, misinterpretation, and even confusion among clinicians. Realizing the importance for standardizing the diverse nomenclature, the Committee for Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery convened a special task force in 1988 to address the problems of terminology related to cervical lymphadenectomy. The specific objectives of the group were as follows: (1) to recommend terminology that adhered to more traditional terms such as “radical” and “modified radical” neck dissection, and to avoid the use of eponyms and acronyms; (2) to define which lymphatic structures and other nonlymphatic structures should be removed or preserved relative to the radical neck dissection; (3) to provide standard nomenclature for the lymph node groups and the nonlymphatic structures; (4) to define the boundaries of resection for lymph node groups; (5) to use terms for the neck dissection procedures that are basic and easy to understand; and (6) to develop a classification on the basis of the biology of the cervical metastases and the principles of oncologic surgery.17

Recently updated by the Committee for Neck Dissection Classification of the American Head and Neck Society (AHNS), the classification is outlined in Table 121-1).9,22,23 The new versions included modifications of the original classification in an effort to remain contemporary and to follow the current philosophy of managing lymph node metastases.

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Radical | Removal of lymph node levels I to V, sternocleidomastoid muscle, spinal accessory nerve, and internal jugular vein. |

| Modified | Removal of lymph node levels I to V (as in radical neck dissection [ND]), but preservation of at least one of the nonlymphatic structures (sternocleidomastoid muscle, spinal accessory nerve, and internal jugular vein). |

| Selective | Preservation of one or more lymph node levels relative to a radical ND. |

| Extended | Removal of an additional lymph node level or group or a nonlymphatic structure relative to a radical ND (muscle, blood vessel, nerve). Examples of other lymph node groups are superior mediastinal, parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, peri-parotid, postauricular, suboccipital, and buccinator. Examples of other nonlymphatic structures are external carotid artery, hypoglossal, and vagus nerves. |

Cervical Lymph Node Groups

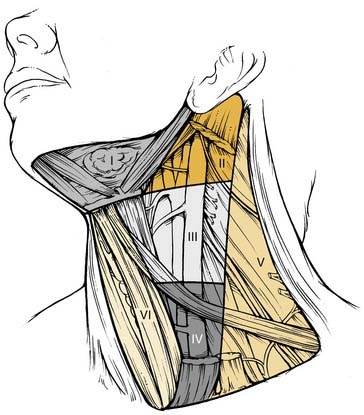

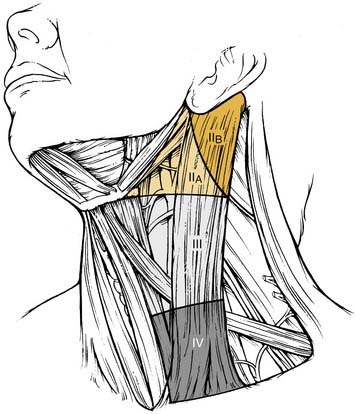

The patterns of spread of cancer from various primary sites in the head and neck to the cervical lymph nodes have been documented by retrospective analyses of large series of patients undergoing neck dissection.12,16,24 The nodal groups at risk for involvement are widespread throughout the neck, extending from the mandible and skull base superiorly to the clavicle inferiorly and from the posterior triangle of the neck laterally to the midline viscera and to the contralateral side of the neck. It is now recommended that the lymph node groups in the neck be categorized according to the level system originally described by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Group (Fig. 121-1).19

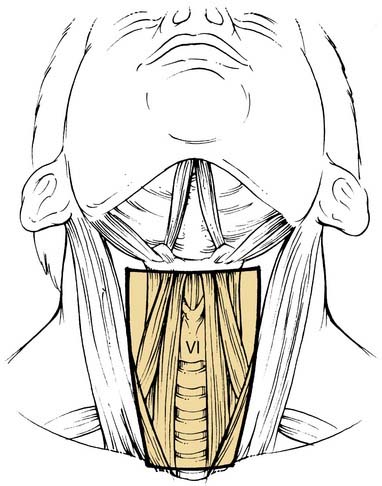

Level VI encompasses the lymph nodes of the anterior compartment of the neck.19,21 This group is made up of nodes that surround the midline visceral structures of the neck, extending from the level of the hyoid bone superiorly to the suprasternal notch inferiorly. On each side, the lateral boundary is formed by the medial border of the carotid sheath. Located within this compartment are the perithyroidal lymph nodes, paratracheal lymph nodes, lymph nodes along the recurrent laryngeal nerves, and precricoid (Delphian) lymph node. These lymph nodes and their connecting lymphatic channels represent pathways of spread from primary cancers originating in the thyroid gland, apex of the piriform sinus, subglottic larynx, cervical esophagus, and cervical trachea.

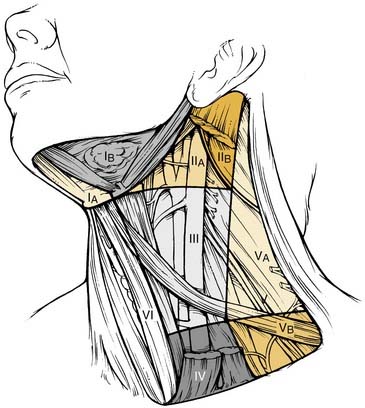

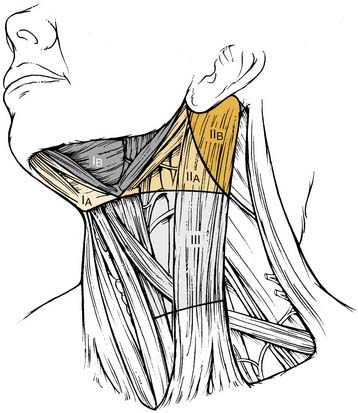

Division of Neck Levels by Sublevels

The 2001 report of the American Head and Neck Society’s Neck Dissection Committee recommended the use of sublevels for defining selected lymph node groups within levels I, II, and V on the basis of the biologic significance, independent of the larger zone in which they lay.21 These are outlined in Figure 121-2 as sublevels IA (submental nodes), IB (submandibular nodes), IIA and IIB (together composing the upper jugular nodes), VA (spinal accessory nodes), and VB (transverse cervical and supraclavicular nodes). The boundaries for each of these sublevels are defined in Table 121-2.

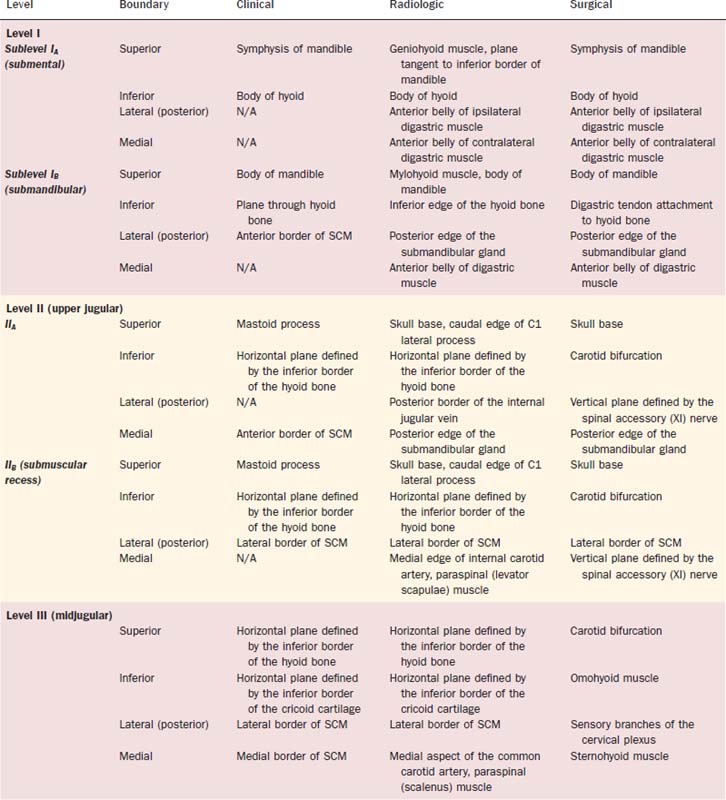

Table 121-2 Lymph Node Groups Found within the Six Neck Levels and the Six Sublevels

| Lymph Node Group | Description |

|---|---|

| Submental (sublevel IA) | Lymph nodes within the triangular boundary of the anterior belly of the digastric muscles and the hyoid bone; these nodes are at the greatest risk of harboring metastases from cancers arising from the floor of the mouth, anterior oral tongue, anterior mandibular alveolar ridge, and lower lip (see Fig. 121-2). |

| Submandibular (sublevel IB) | Lymph nodes within the boundaries of the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, the stylohyoid muscle, and the body of the mandible, including the preglandular and postglandular nodes and the prevascular and postvascular nodes. The submandibular gland is included in the specimen when the lymph nodes within this triangle are removed. These nodes are at greatest risk for harboring metastases from cancers arising from the oral cavity, the anterior nasal cavity, and the soft tissue structures of the midface and the submandibular gland (see Fig. 121-3). |

| Upper jugular (sublevels IIA and IIB) | Lymph nodes located around the upper third of the internal jugular vein and the adjacent spinal accessory nerve, extending from the level of the skull base above to the level of the inferior border of the hyoid bone below. The anterior (medial) boundary is the stylohyoid muscle (the radiologic correlate is the vertical plane defined by the posterior surface of the submandibular gland), and the posterior (lateral) boundary is the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Sublevel IIA nodes are located anterior (medial) to the vertical plane defined by the spinal accessory nerve. Sublevel IIB nodes are located posterior (lateral) to the vertical plane defined by the spinal accessory nerve. The upper jugular nodes are at greatest risk for harboring metastases from cancers arising from the oral cavity, nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and parotid gland (see Fig. 121-3). |

| Middle jugular (level III) | Lymph nodes located around the middle third of the internal jugular vein, extending from the inferior border of the hyoid bone above to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage below. The anterior (medial) boundary is the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle, and the posterior (lateral) boundary is the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. These nodes are at greatest risk for harboring metastases from cancers arising from the oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx (see Fig. 121-3). |

| Lower jugular (level IV) | Lymph nodes located around the lower third of the internal jugular vein, extending from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage above to the clavicle below. The anterior (medial) boundary is the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle, and the posterior (lateral) boundary is the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. These nodes are at greatest risk of harboring metastases from cancers arising from the hypopharynx, thyroid, cervical esophagus, and larynx (see Fig. 121-3). |

| Posterior triangle (sublevels VA and VB) | This group is composed predominantly of the lymph nodes located along the lower half of the spinal accessory nerve and the transverse cervical artery. The supraclavicular nodes are also included in the posterior triangle group. The superior boundary is the apex formed by the convergence of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles; the inferior boundary is the clavicle, the anterior (medial) boundary is the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the posterior (lateral) boundary is the anterior border of the trapezius muscle. Sublevel VA is separated from sublevel VB by a horizontal plane marking the inferior border of the anterior cricoid arch. Thus sublevel VA includes the spinal accessory nodes, whereas sublevel VB includes the nodes that follow the transverse cervical vessels and the supraclavicular nodes (with the exception of Virchow’s node, which is located in level IV). The posterior triangle nodes are at greatest risk for harboring metastases from cancers arising from the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and cutaneous structures of the posterior scalp and neck (see Fig. 121-3). |

| Anterior compartment (level VI) | Lymph nodes in this compartment include the pretracheal and paratracheal nodes, the precricoid (Delphian) node, and the perithyroidal nodes, including the lymph nodes along the recurrent laryngeal nerves. The superior boundary is the hyoid bone, the inferior boundary is the suprasternal notch, and the lateral boundaries are the common carotid arteries. These nodes are at greatest risk for harboring metastases from cancers arising from the thyroid gland, glottic and subglottic larynx, apex of the piriform sinus, and cervical esophagus (see Fig. 121-2). |

| Superior mediastinum (optional—level VII) | These nodes represent an extension of the paratracheal lymph nodes chain extending inferiorly below the suprasternal notch along each side of the cervical trachea to the level of the innominate artery. |

The risk of nodal disease in sublevel IIB is greater for tumors arising in the oropharynx as compared with the oral cavity and larynx.25–32 Thus in the absence of clinical nodal disease in sublevel IIA, it is likely not necessary to include sublevel IIB for tumors arising in these latter sites. The dissection of the node-bearing tissue of sublevel IIB (submuscular recess) creates a risk of morbidity. Adequate exposure necessitates significant manipulation of the spinal accessory nerve and may account for trapezius muscle dysfunction observed in a significant minority of patients after an SND. Sublevel IA is a zone from which many surgeons do not remove lymph nodes unless the primary cancer involves the floor of the mouth, the lip, or structures of the anterior midface or there is obvious lymphadenopathy.

Correlation of Neck Level Boundaries with Anatomic Markers Depicted Radiologically

Radiologists have now identified landmarks that more accurately identify the location of lymph nodes according to the level system (Table 121-3).33,34 Using radiologic landmarks, level I includes all of the nodes above the level of the lower body of the hyoid bone, below the mylohyoid muscles, and anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the submandibular gland. Level IA represents those nodes that lie between the medial margins of the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, above the level of the lower body of the hyoid bone, and below the mylohyoid muscle (these were previously classified as submental nodes). Level IB represents the nodes that lie below the mylohyoid muscle, above the level of the lower body of the hyoid bone, posterior and lateral to the medial edge of the ipsilateral anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image tangent to the posterior surface of the submandibular gland on each side of the neck (these are also referred to as submandibular nodes). Level II extends from the skull base at the lower level of the bony margin of the jugular fossa to the level of the lower body of the hyoid bone. Level II nodes lie anterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial image through the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and they lie posterior to a transverse line drawn on each axial scan through the posterior edge of the submandibular gland. However, any nodes that lie medial to the internal carotid artery (ICA) are retropharyngeal and thus not level II.

Neck Dissection Classification

The classification for neck dissection recommended by the American Head and Neck Society’s committee is based on the following rationale: (1) that radical neck dissection is the standard basic procedure for cervical lymphadenectomy, and all other procedures represent one or more modifications of this procedures; (2) when the modification of the radical neck dissection involves the preservation of one or more nonlymphatic structures, the procedure is called modified radical neck dissection; (3) when the modification involves the preservation of one or more lymph node groups that are routinely removed in the radical neck dissection, the procedure is called SND; and (4) when the modification involves the removal of additional lymph node groups or nonlymphatic structures relative to the radical neck dissection, the procedure is called extended radical neck dissection (see Table 121-1).

Radical Neck Dissection

DEFINITION

This procedure includes the removal of all ipsilateral cervical lymph node groups extending from the body of the mandible superiorly to the clavicle inferiorly and from the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle, hyoid bone, and contralateral anterior belly of the digastric muscle anteriorly to the anterior border of the trapezius muscle posteriorly.22 Included are all lymph node groups from levels I through V, the spinal accessory nerve, the internal jugular vein, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 121-3). It does not include the removal of the postauricular and suboccipital nodes, the periparotid nodes (except for a few nodes located in the tail of the parotid gland), the perifacial and buccinator nodes, the retropharyngeal nodes, and the paratracheal nodes.

Technique

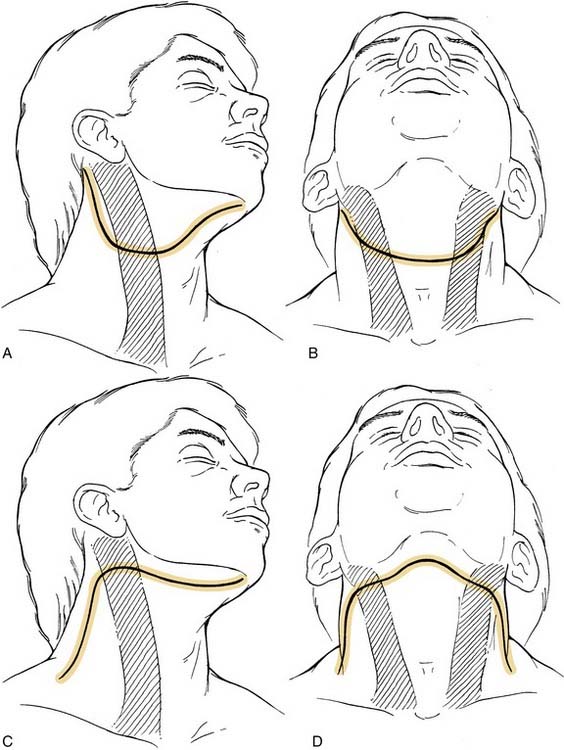

INCISION PLANNING

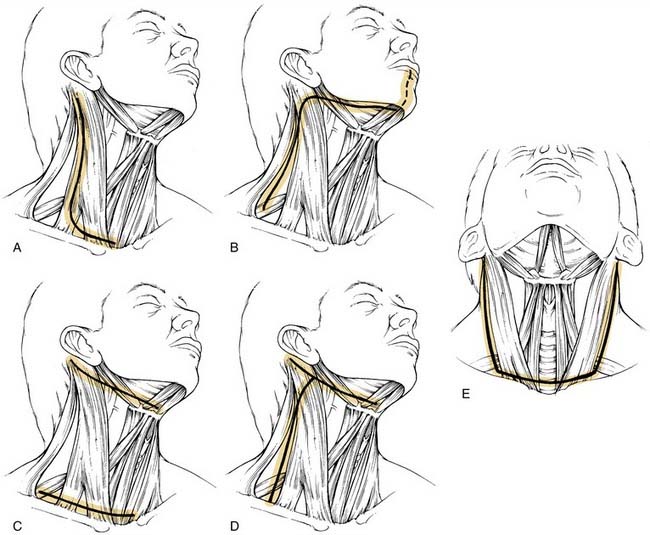

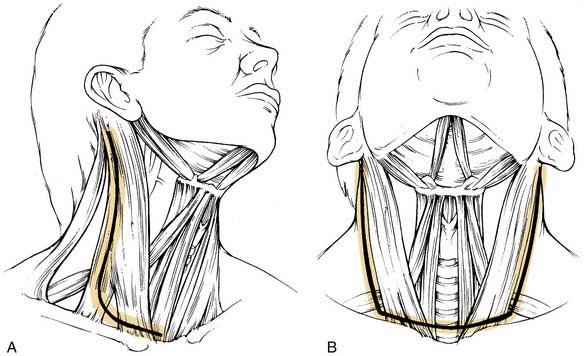

The incision is planned for optimal exposure of all lymph node levels to be dissected (levels I to V) and to preserve as much blood supply as possible. The neck flaps raised should be broadly based, either superiorly or inferiorly, and preferably to avoid any trifurcations, particularly overlying the carotid sheath. Incisions that best fit these criteria are the hockey stick and boomerang patterns; the McFee incision; and, in patients undergoing bilateral neck dissection, the apron incision, which is a bilateral hockey stick incision (Fig. 121-4). Other incisions use trifurcations that overlie the carotid sheath, although modifications of the Schobinger incision include placing the trifurcation more laterally based. Although the boomerang incision may be somewhat less aesthetically pleasing, it is an excellent alternative to use in conjunction with oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors wherein exposure of the primary site involves extending the incision through the lip for a mandibulotomy approach.

FLAP ELEVATION

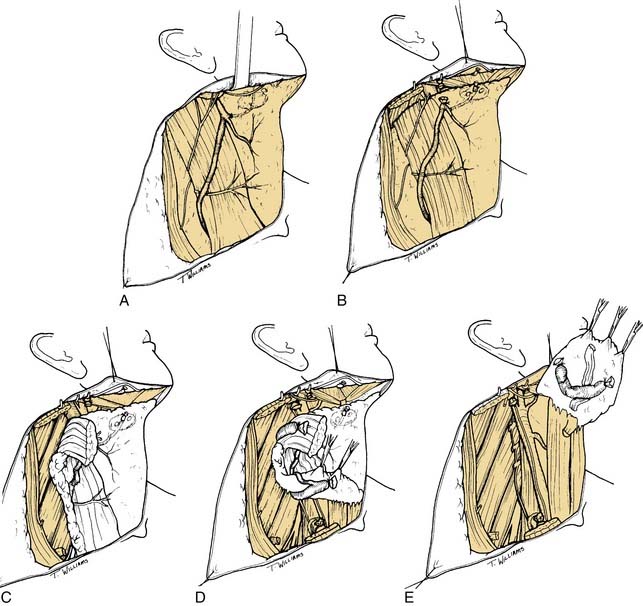

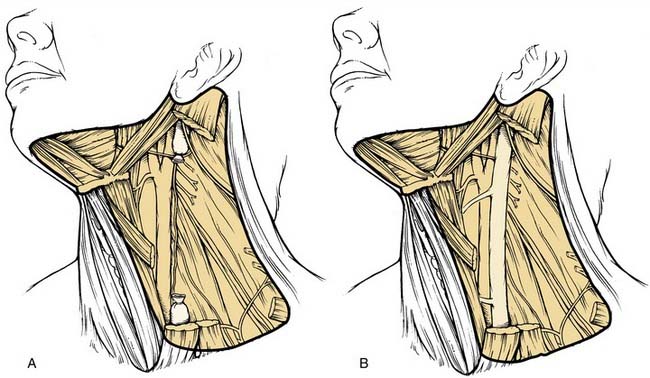

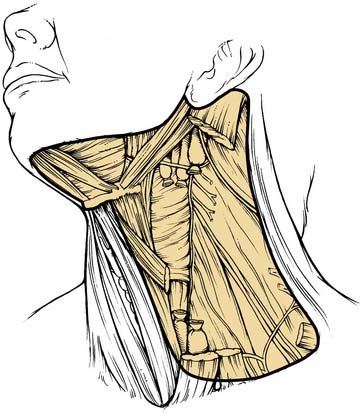

The initial incision is carried through skin and platysma muscle, although the platysma is deficient in the midline and the lateral-most parts of the incision. This anatomic feature can be used to reapproximate the flaps at the time of closure because the platysmal muscle edges serve as “natural hash marks.” The flap is raised in the subplatysmal plane so that the external jugular vein and the greater auricular nerves are not included in the flap (Fig. 121-5A). Although these structures will ultimately be sacrificed in the radical neck dissection, in SND procedures, they are routinely preserved. When there is gross pathologic evidence of tumor extension through the platysma muscle, with or without skin involvement, the area of disease involvement should also be removed and modifications of the skin flap may be required. Identification of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve is performed after complete elevation of the skin flaps superiorly and inferiorly to expose all of the lymph node levels of the neck. It is recommended that the anterior facial vein be ligated and retracted superiorly to protect this nerve only after the superior skin flap is raised. This allows proper assessment of the prevascular and postvascular lymph nodes in the submandibular triangle, which will need to be removed. Therefore it is best to incise the submandibular fascia at the lower border of the submandibular gland and to carefully raise this fascia off of the submandibular gland superiorly to the level of the lower border of the mandible as a separate flap. Usually the mandibular branch of the facial nerve may be seen as this fascia is raised (see Fig. 121-5B).

DISSECTION OF THE POSTERIOR TRIANGLE

The subsequent order of dissection is a matter of individual preference, although there is some oncologic rationale for dissecting from below upward rather than from above downward. Thus the next step is to expose the anterior border of the trapezius muscle from its superior aspect, where it converges with the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, to its inferior aspect, where it approaches the clavicle (see Fig. 121-5C). The fibrofatty tissue is then incised along its anterior border beginning superiorly and working inferiorly to expose the muscular floor of the posterior triangle. In so doing, the spinal accessory nerve will be severed at the point at which it enters the trapezius muscle in the lower aspect of the posterior triangle. After this step has been completed, the floor of the posterior triangle at its inferior extent is next exposed by incising through the fibrofatty tissue immediately above the superior border of the clavicle. This requires incising through the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle and the fibrofatty tissue overlying the brachial plexus. In this region, the transverse facial artery will be encountered immediately overlying the muscular floor of the triangle; this artery should be preserved unless there is gross disease involving the region. The fibrofatty contents of the posterior triangle are then mobilized anteriorly, lifting them away from the floor of the neck, which, in this region, is formed by the splenius capitis, levator scapulae, and scalene muscles. It is important to remain superficial to the prevertebral fascia during this step of the operation to prevent injury to the phrenic nerve and the brachial plexus. As the fibrofatty tissue is swept in a lateral-to-medial direction, the sensory branches of the cervical plexus will be encountered and divided.

ANTERIOR TRIANGLE DISSECTION

As the fibrofatty tissue is elevated medially toward the carotid sheath, it will be necessary to incise the mastoid attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the clavicular attachments (see Fig. 121-5D). The carotid sheath will be exposed, and identification of the common carotid artery and vagus nerve may be made. Attention should be given to preserving the cervical sympathetic chain, which is closely applied to the prevertebral fascia behind the carotid sheath. The plane of dissection will be carried between the vagus nerve and the carotid artery below and the internal jugular vein above. Thus the internal jugular vein may be mobilized from the skull base superiorly to its inferior aspect near the clavicle; ties may then be placed around the upper and lower ends of the internal jugular vein, thereby allowing ligation and complete mobilization. When incising the soft tissue contents of the lower medial aspect of the neck, lymphatic channels will be encountered, particularly on the left side. It is imperative to precisely identify these and ligate them immediately as they are encountered. The thoracic duct is located to the right of and behind the left common carotid artery and the vagus nerve. From here, it arches upward, forward, and laterally, passing behind the internal jugular vein and in front of the anterior scalene muscle and the phrenic nerve; it then opens into the internal jugular vein, subclavian vein, or angle formed by the junction of these two vessels. The duct is anterior to the thyrocervical trunk and the transverse cervical artery. To prevent a chyle leak, the surgeon should also remember that the thoracic duct may be multiple in its upper end and that, at the base of the neck, it usually receives the jugular trunk, a subclavian trunk, and maybe other minor lymphatic trunks that should be individually divided and ligated or clipped.

At this point, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is identified, and the soft tissue attachments of the neck contents lying superior to the muscle are divided, including the sternocleidomastoid muscle as it attaches to the mastoid process, vascular channels extending into the postauricular region and parotid gland, the tail of the parotid gland that extends downward inferior to the level of the digastric muscle, and soft tissue attachments to the angle of the mandible. After completion of this part of the dissection, all of the lower contents of the neck dissection specimen should be freely mobile, and the only remaining attachments are the upper end of the internal jugular vein and the undissected contents of the submandibular triangle and the submental triangle (see Fig. 121-5E).

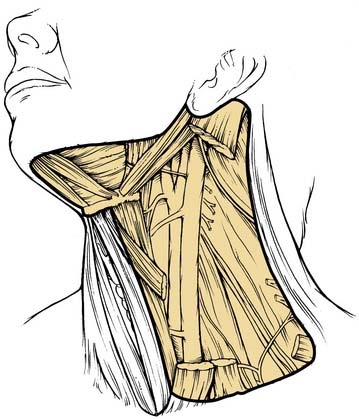

Modified Radical Neck Dissection

DEFINITION

A modified radical neck dissection is defined as the en bloc removal of lymph node–bearing tissue from one side of the neck (levels I to V). The dissection extends from the inferior border of the mandible above to the clavicle below and from the lateral border of the strap muscles medially to the anterior border of the trapezius muscle laterally. Unlike the radical neck dissection, there is preservation of one or more of the following structures in the modified radical dissection: spinal accessory nerve, internal jugular vein, and sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 121-6). The major purpose of these modifications relates to the morbidity encountered when the spinal accessory nerve is removed. Although the degree of morbidity is less for removal of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the internal jugular vein, this issue becomes far more important if bilateral neck dissections are required. Simultaneous sacrifice of both internal jugular veins may result in severe swelling of the face with increased intracranial pressure.

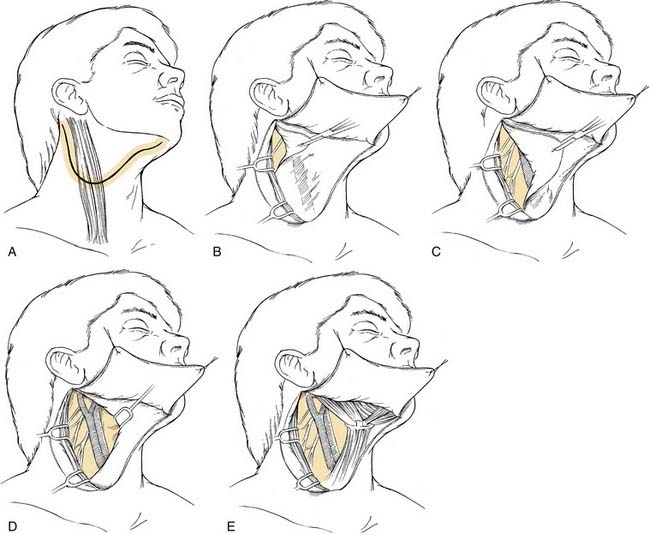

TECHNIQUE

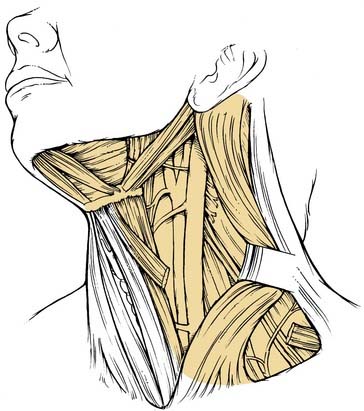

Unlike what is found in the radical neck dissection procedure, the next step is to identify the spinal accessory nerve. This is initially done in the posterior triangle from which the nerve exits at or around Erb’s point (Fig. 121-7A). The nerve lies superficially in the fibrofatty contents of the posterior triangle and usually may be identified by careful spreading of the fibrofatty tissue; the use of a nerve stimulator may assist this process. Once located, the nerve is isolated and dissected away from the underlying fibrofatty contents from Erb’s point medially to the point at which it enters the anterior border of the trapezius muscle laterally (see Fig. 121-7B). The nerve is next isolated in its superior third, which is done by incising the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle from its attachment superiorly at the mastoid to its lowermost attachment at the sternal head. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted laterally as the fibrofatty soft tissue contents anterior to this muscle are dissected away from it, and the many arcades of small blood vessels coursing between the muscle and the soft tissue are divided. This part of the procedure mobilizes the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle along its full extent. As the muscle is retracted laterally in its upper portion, the spinal accessory nerve is seen entering its deep surface (see Fig. 121-7C). From this point, the nerve is traced superiorly by dividing the overlying fibrofatty contents until the posterior belly of the digastric muscle is identified. This muscle is retracted superiorly to gain exposure to the superior end of the internal jugular vein near the jugular foramen. The posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be freed completely from the underlying fibrofatty contents all the way from its mastoid attachment above to its clavicular attachment below. Except for its course through this muscle, the spinal accessory nerve is now completely mobilized from its entry into the anterior border of the trapezius muscle below to its superior extent at the skull base above.

The fibrofatty tissue in the posterior triangle is separated from the entire anterior border of the trapezius muscle and is mobilized from a lateral to a medial direction. Tissue lying superficial to the spinal accessory nerve as it courses across the posterior triangle should be divided immediately above the spinal accessory nerve so that it may be passed along with its deep component beneath the nerve and the elevated sternocleidomastoid muscle (see Fig. 121-7D). After the fibrofatty contents have been dissected and swept over the carotid artery, vagus nerve, and internal jugular vein, the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be retracted laterally and the contents passed underneath the muscle for subsequent dissection of the anterior triangle of the neck (see Fig. 121-7E). Careful sharp dissection will allow for separation of these contents from the carotid artery and the jugular vein. This dissection is continued until the sternohyoid muscle, which is the medial boundary of anterior triangle contents in the lower neck, is reached. The branches of the internal jugular vein are usually ligated to allow a thorough clearance of the anterior triangle contents. Dissection is carried superiorly to remove the fibrofatty tissue attachments overlying the internal jugular vein at the level of the skull base. The retromandibular vein may be preserved, but the anterior facial vein needs to be ligated (see Fig. 121-7F). Subsequent dissection is then performed to remove the contents of the submandibular and submental triangles.

Sacrifice of one or two of the nonlymphatic structures of the neck (i.e., spinal accessory nerve, sternocleidomastoid muscle, and internal jugular vein) may become necessary as a result of gross involvement by cancer intraoperatively, although the operation continues to be called a modified radical neck dissection as long as at least one of these structures is preserved (Fig. 121-8).

Selective Neck Dissection (see Key Indicator Video on website)

RATIONALE

Although the concept of SND dates back to procedures used for treating lip cancer, its broader adoption to treat other cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract was popularized by surgeons at the MD Anderson Cancer Center.20 It was based on removing lymph node groups that were at highest risk in patients with N0 nodal disease. Studies have shown that this procedure has the same therapeutic value as more extensive neck dissections16; it is also intended to preserve functionally and cosmetically relevant structures as a secondary goal.

The topographic distribution of lymph node metastases appears to be predictable in patients with previously untreated squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, particularly in those with early disease. The basic anatomic studies of Rouviere35 and Fisch and Sigel36 showed that lymphatic drainage of the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck follow relatively constant and predictable routes. The clinical study by Lindberg in 197212 showed that the lymph node groups most frequently involved in patients with carcinoma of the oral cavity are the jugulodigastric and midjugular nodes. In addition, the nodes in the submandibular triangle are frequently involved in patients with carcinoma of the floor of the mouth, the anterior oral tongue, and the buccal mucosa. Lindberg also noted that tumors frequently metastasize to both sides of the neck and may skip the submandibular and jugulodigastric nodes, metastasizing first to the midjugular region. The Lindberg study showed that, in the absence of metastases to the first echelon nodes, tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx rarely involve the lower jugular and posterior triangle nodes. Similar findings were reported by Skolnik in 1976,14 who, in a study of radical neck dissection specimens, found no metastases in the nodes of the posterior triangle of the neck in radical neck dissections, regardless of the site of the primary tumor or the presence or absence of metastases in the jugular nodes. Further evidence subsequently has been provided by Shah25 in a retrospective study of radical neck dissection specimens performed for patients with oral cavity and larynx or laryngopharyngeal metastases. Shah demonstrated that tumors of the oral cavity metastasize most frequently to neck nodes in levels I, II, and III, whereas carcinomas of the pharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx involve mainly the nodes in levels II, III, and IV. Whenever nodes were found in other areas, there was also positive disease in the areas of highest risk.

Some authorities believe that SND is, in essence, a procedure for staging the necks of patients whose tumors are amenable to treatment with surgery alone. In patients who have this procedure done in conjunction with the excision of the primary tumor, further information about the status of the nodal disease is provided. If there is evidence of multiple lymph node metastases or extracapsular spread in the neck dissection contents, then postoperative radiotherapy is indicated. Byers and colleagues37 also reported a lower rate of regional recurrence among patients with N1 disease if postoperative radiation therapy was administered. More intensive therapy may be used for patients who have more aggressive tumors.

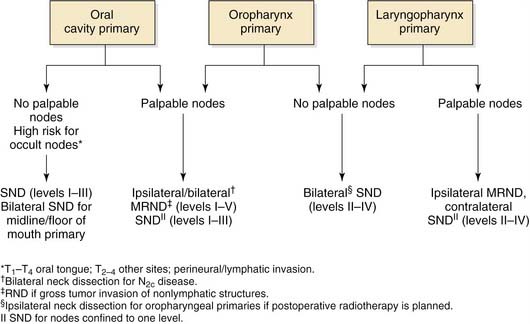

Selective Neck Dissection for Oral Cavity Cancer

DEFINITION AND RATIONALE

SND is recommended for patients with oral cavity cancer who are at risk of harboring occult nodal disease (Fig. 121-9). Also, SND can be performed for patients with low-volume nodal disease (N1) located in the upper neck provided that postoperative radiation therapy is part of the treatment plan. Tumors originating in this region, particularly in the subsites of the oral tongue and the floor of the mouth, have a high propensity to metastasize early, regardless of size and differentiation. Primary echelons for nodal spread include the submental, submandibular, upper jugular, and middle jugular groups. In patients with tongue cancer, the lower jugular lymph node groups (level IV) are also at risk.38 Even when there is no clinical evidence of nodal disease, there is at least a 20% risk for occult disease associated with these lesions. Unless the management of choice for the primary lesion is radiotherapy, elective neck dissection with removal of levels I through III (level IV for those with tongue cancer) is the minimal recommended treatment for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity associated with N0 nodal disease. For patients with palpable nodal disease, it is usually necessary to perform a modified radical neck dissection, but a selective removal of levels I through IV is an appropriate alternative when the nodal disease is confined to levels I and II. With the possible exception of a solitary metastatic node without extracapsular extension, postoperative radiation therapy is usually indicated for all patients undergoing SND who have positive pathologic nodes in the specimen.37 Elective cervical lymphadenectomy of the contralateral neck is indicated for patients with primary lesions involving the floor of the mouth or the ventral surface or with midline involvement of the tongue, in whom ipsilateral neck dissection is planned and in whom there are no definite indications for postoperative radiotherapy. Contralateral therapeutic neck dissection is indicated for patients with clinically N2c disease.

TECHNIQUE

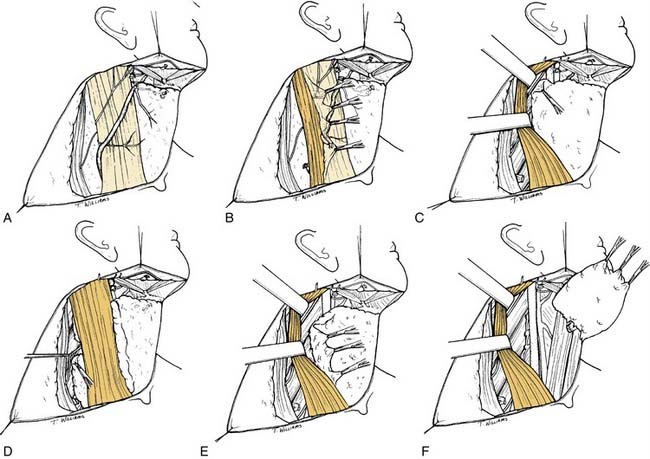

When an ipsilateral supraomohyoid neck dissection is planned, a modified apron incision is made to provide adequate exposure of levels I through III (Fig. 121-10A). If bilateral neck dissection is necessary, the horizontal component of the apron incision is carried across the midline to the other side of the neck (bilateral apron incision; see Fig. 121-10B). The ipsilateral and bilateral apron incisions are also appropriate for exposure of the primary disease when a pull-through exposure is indicated. When it is necessary to split the lip for access to the primary tumor, the medial component of the ipsilateral apron incision may be extended for this purpose. If bilateral neck dissection is planned and a lip-splitting incision is also required, a bilateral boomerang incision is substituted for the bilateral apron incision (see Fig. 121-10C). This neck incision pattern is also preferred for those with more advanced nodal disease associated with oral cavity primaries in whom it is necessary to dissect all five levels of the ipsilateral neck. The boomerang incision is also preferred for patients with stage N2c disease because it may be extended across the midline for exposure of all levels of the contralateral lymph nodes (see Fig. 121-10D).

For the removal of levels I through III, the modified apron skin flap is raised in the subplatysmal plane until there is exposure of the upper two thirds of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, mastoid process, body of the mandible, and mandibular symphysis (Fig. 121-11A and B). It is preferred not to raise the fascia off of the submandibular gland until the subplatysmal flap is first elevated to the level of the body of the mandible, which permits a more accurate assessment of the submandibular triangle for assessing tumor involvement of the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. After this possibility is excluded, the fascia overlying the submandibular gland is carefully raised as a separate flap to avoid injuring the mandibular branch of the facial nerve. This branch is often seen within the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, but, with careful dissection of this layer, the nerve may be protected and preserved.

Next, an incision is made in the investing layer of the deep fascia at the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Care is taken to not injure the external jugular vein and branches of the greater auricular nerve that lie lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle but posterior to the fascial incision being made. Because lymph nodes associated with the external jugular vein are almost never involved with aerodigestive tract carcinomas, these structures are left undisturbed. The fibrofatty contents of the anterior triangle are peeled away first from the anterior border and then from the medial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle all the way from a point close to the mastoid process above down to the level of the omohyoid muscle below, stopping when the posterior border of the muscle is reached. Although the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is being separated, the spinal accessory nerve comes into view as it enters the muscle (see Fig. 121-11C). This nerve is dissected free of its surrounding fibrofatty tissue from the level of the skull base adjacent to the internal jugular vein to its point of entry into the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It is necessary to dissect along the inferior border of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and to retract it supralaterally to provide adequate exposure of the upper carotid sheath near the skull base. Fibrofatty tissue is also dissected away from the inferior border of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle as far posteriorly as the attachment of the mastoid process. This triangle formed by the digastric muscle, spinal accessory nerve, and sternocleidomastoid muscle outlines the triangular packet of tissue-bearing lymph nodes belonging to level II. It is important to separate this triangular packet from the underlying paraspinal muscles and to pass it under the spinal accessory nerve (see Fig. 121-11D). The dissection is continued inferiorly by incising along the fibrofatty tissue corresponding with the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the level of the omohyoid muscle. Care is taken to not cut across the sensory branches of the cervical plexus as the incision is carried down to the muscular floor. When the sensory branches of the cervical plexus are encountered, the fibrofatty tissue is dissected in a plane that is superficial to these nerves (see Fig. 121-11E). At this point in the procedure, it is important to carefully inspect and palpate the lower jugular chain and the posterior triangle for evidence of nodal disease. If found, the dissection of the lymph-node-bearing tissue would have to be extended to encompass level IV and the posterior triangle (level V), thus converting the operation to a modified radical neck dissection. For this purpose, a lower cervical flap would then be raised for adequate exposure of the clavicle and the anterior border of the trapezius.

After completion of the lateral boundary of dissection, the lymph node–bearing tissue is swept medially in a plane immediately above the fascia of the paraspinal muscles. The sensory branches of the cervical plexus may be preserved only when level V dissection is not performed. This maneuver allows the lymph node–bearing tissue to be swept over the carotid sheath and permits exposure of its structures from the level of the clavicle or omohyoid muscle below to the skull base above. Sharp dissection is used to remove the fascia overlying the sheath, which usually includes preserving the internal jugular vein if a tissue plane can be readily identified. Next, the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle is skeletonized along its superior border to the level of the hyoid bone. The hyoid bone is also skeletonized medially, as is the anterior belly of the contralateral digastric muscle; this completes the medial boundary of dissection. The fibrofatty tissue is dissected from below at the level of the omohyoid muscle in a superior direction toward the submandibular triangle. After the lymph node–bearing tissue in the submental triangle has been cleared, the contents of the submandibular triangle are removed to complete the neck dissection (see Fig. 121-11). To ensure complete removal of all lymph nodes from this region, it is important to dissect along the fascial planes of the muscles within this triangle rather than enucleate the submandibular gland only, which includes dissecting the preglandular nodes underneath the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the prevascular and postvascular nodes along the lower border of the body of the mandible. It is usually not necessary to remove the perifacial nodes lying lateral to the mandibular body, unless the primary cancer involves the buccal mucosa, upper gum, or upper lip. Dissection of this latter nodal group increases the risk of injury to the mandibular branch of the facial nerve. After completion of the dissection, the excised tissue is separated according to the level of the lymph node groups, each level being submitted separately for pathologic evaluation. Before closing the incisions, a single drain is placed in the surgical bed extending inferiorly from the digastric muscle above to a separate cutaneous puncture site made at the most dependent region below the skin incision. The drain is placed on continuous suction. A second drain is placed in the contralateral neck for bilateral procedures. The drain is usually removed 3 days after surgery, if the fluid collection is less than 20 mL/24 hours.

Selective Neck Dissection for Oropharyngeal, Hypopharyngeal, and Laryngeal Cancer

DEFINITION AND RATIONALE

The procedure of choice for these anatomic sites is SND (levels II to IV), and its boundaries are outlined in Figure 121-12; it is also called a lateral neck dissection. The procedure refers to the removal of the upper jugular lymph nodes (level II), the midjugular lymph nodes (level III), and the lower jugular lymph nodes (level IV). The superior limit of dissection is the skull base, and the inferior limit is the clavicle. The anterior (medial) limit is the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle and the stylohyoid muscle. The posterior (lateral) limit of the dissection is marked by the cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus and the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. In the case of cancers involving the oropharynx and the hypopharynx, there is evidence indicating that the lateral retropharyngeal nodes are also at risk. Level IIB is at greater risk for metastases associated with oropharyngeal lesions relative to laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Thus if level IIB is excluded (as is sometimes done for N0 laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers), the procedure would be designated SND (IIA, III, and IV). When the risk for lymphatic metastases is bilateral, the procedure of choice is a bilateral SND (II to IV). If the retropharyngeal lymph nodes are included, as in the case of cancers involving the pharyngeal wall, the procedure is designated SND (II to IV, retropharyngeal nodes). If the nodes in level VI are removed, as in the case of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers extending below the level of the glottis, the procedure is designated SND (II to IV and VI).

It should be noted that there is a controversy over which selective neck dissection is indicated for an oropharyngeal cancer without known metastasis to the neck (N0). Although the “classic” findings by Shah25 and others39–42 showed the pattern of lymph node to be involved is in levels II to IV, other studies have suggested that the levels at risk are I to III.43,44 One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be the fact that it is easy to confuse nodes located posterior and deep to the submandibular gland with level IB, when in essence they are in level IIA. The same mistake could be done when dividing the specimen ex vivo into the different levels. Another possible explanation would be that an original oropharyngeal base of tongue cancer involves the oral tongue as well, thus putting level Ib at higher risk.

TECHNIQUE

The incision should allow for adequate exposure of levels II through IV and, should occult disease be found, exposure of level V as well. The hockey stick incision as described for radical and modified radical neck dissection is useful for this purpose; it may also be extended across the midline and carried along the contralateral neck as a broadly based apron flap or bilateral hockey stick incision (Fig. 121-13). After the neck flaps have been raised, the fibrofatty contents of the anterior triangle are removed en bloc, including the lymph nodes lying along the internal jugular vein from the skull base superiorly to the clavicle inferiorly. The dissection proceeds by incising along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and by separating it from its underlying attachments to the fibrofatty tissue. Care is taken to identify the spinal accessory nerve as it enters the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Then it is skeletonized from its entry point into the muscle inferiorly and into the skull base superiorly, wherein it lies deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and lateral to the internal jugular vein. As described for the supraomohyoid neck dissection, the fibrofatty tissue deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle is incised and separated from the underlying splenius and levator muscles. The sensory branches of the cervical plexus may also be preserved by limiting the mobilization of fibrofatty tissue to the region superficial to these nerve branches. The contents are swept medially over the internal jugular vein, thereby exposing the full length of the vein from the skull base above to the clavicle below. At the lower end, care should be taken to meticulously identify and ligate any lymphatic channels encountered. On the left side, the thoracic duct will frequently be encountered; this structure must be carefully separated away from the fibrofatty tissue, avoiding any injury. If injury occurs, a repair must immediately be performed with fine, nonabsorbable suture material (e.g., silk, monofilament synthetic); occasionally this will necessitate ligation of the duct. After the internal jugular vein has been completely skeletonized, the remainder of the fibrofatty contents of the anterior triangle is mobilized by skeletonizing the medial border of the sternohyoid muscle and the stylohyoid muscle. The branches of the internal jugular vein in the neck may be sacrificed to assist this process, although the communicating branch to the anterior facial and retromandibular veins may be easily preserved.

Selective Neck Dissection for Cutaneous Malignancies

DEFINITION AND RATIONALE

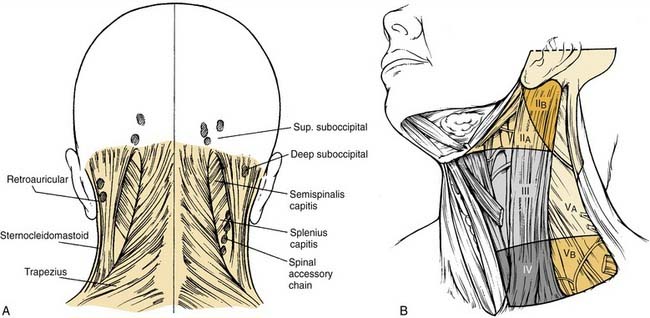

The operation of choice depends on the location of the lesion and the adjacent lymph node groups, which are most likely to harbor metastatic disease. In the case of cancers involving the posterior scalp and upper neck, the procedure of choice is SND (II to V, postauricular, and suboccipital) (Fig. 121-14). This particular version is also called the posterolateral neck dissection; it is primarily used to eradicate nodal metastases associated with cutaneous malignancies and soft tissue sarcomas.9

It involves the removal of the suboccipital lymph nodes, retroauricular lymph nodes, upper jugular lymph nodes (level II), middle jugular lymph nodes (level III), lower jugular lymph nodes (level IV), and nodes of the posterior triangle of the neck (level V). The superior limit of dissection is the skull base anteriorly and the nuchal ridge posteriorly, and the inferior limit is the clavicle. The medial (anterior) limit is the lateral border of the sternohyoid muscle and the stylohyoid muscle; the lateral (posterior) limit is the anterior border of the trapezius muscle inferiorly and the midline of the neck superiorly. It is common to all sites that the lymphatic pathways for the seeding of tumor to the first and secondary echelon nodes involve the posterior auricular, occipital, posterior triangle, and jugular groups (see Fig. 121-14). Thus the dissection is designed to encompass the lymph node–bearing fibrofatty tissue of the posterior and lateral compartments of the neck. In addition, it is important to remove the intervening subdermal fat and underlying fascia between the lymph node groups and the primary disease, which ensures the removal of smaller nests of metastasizing tumor cells that are characteristic of malignancies originating in cutaneous soft tissue. For cutaneous malignancies arising on the preauricular, anterior scalp, and temporal regions, the elective neck dissection of choice is SND (parotid and facial nodes, levels IIA, IIB, III, and VA, and the external jugular nodes). For cutaneous malignancies arising on the anterior and lateral face, the elective neck dissection of choice is SND (parotid and facial nodes, levels IA, IB, II, and III). The development of techniques of lymphatic mapping may have a future role in specifically defining unpredictable lymphatic echelons of risk for cutaneous malignancies.

Selective Neck Dissection for Cancer of the Midline Structures of the Anterior Lower Neck

DEFINITION AND RATIONALE

The procedure of choice is SND (level VI) and is often called the anterior neck dissection or the central compartment dissection (Fig. 121-15). The procedure is most often indicated with or without dissection of other neck levels for thyroid cancer, advanced glottic and subglottic larynx cancer, advanced piriform sinus cancer, and cervical esophageal/tracheal cancer. This refers to the removal of the lymph nodes within the central compartment of the neck including the paratracheal, precricoid (Delphian), and perithyroidal nodes and the nodes located along the recurrent laryngeal nerves. The superior limit of dissection is the body of the hyoid bone, and the inferior limit is the suprasternal notch; the lateral limits are defined by the medial border of the carotid sheath (the common carotid artery). This neck dissection does not have a contralateral counterpart, and it assumes that the lymph nodes are removed on both sides of the trachea. In the case of metastases extending below the level of the suprasternal notch, dissection of the superior mediastinal nodes may be indicated, in which case the procedure is designated SND (VI, superior mediastinal nodes or the optional VII). Exposure of this latter region may require removing the manubrium and possibly one or both sternal heads of the clavicles.

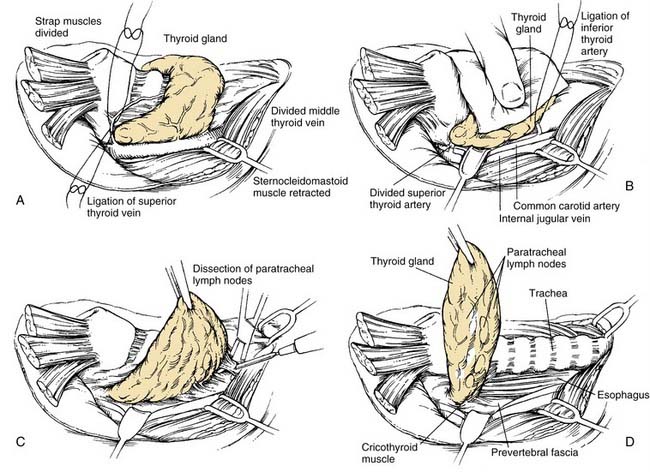

TECHNIQUE

If there is an indication to dissect the lateral and posterior neck compartments, this procedure is done first. Then the strap muscles are either divided near the attachments at the sternum or mobilized and retracted laterally. The carotid artery is skeletonized along its medial border as far superiorly as the superior thyroid artery (Fig. 121-16A). The ipsilateral lobe of the thyroid gland is mobilized along its lateral border by dividing the fascia and its arterial and venous supply (see Fig. 121-16B). The recurrent laryngeal nerve is identified inferiorly as it courses the tracheoesophageal groove. If the larynx is to be removed, protection of the nerve is unnecessary. The fibrofatty contents of each side of the anterior compartment then may be removed by excising all of the loose areolar tissue located between the carotid artery laterally and the trachea medially (see Fig. 121-16C); the thyroid lobe also is removed as part of this en bloc resection (see Fig. 121-16D). The parathyroid glands should be identified and reimplanted into the sternocleidomastoid muscle. If it is necessary to completely remove nodal-bearing tissue from the entire anterior compartment, the procedure is completed on the contralateral side of the trachea. Thus a total thyroidectomy is performed, and all of the parathyroid glands are reimplanted. The dissection is carried superiorly as far as the hyoid bone and inferiorly as far as the suprasternal notch. If there is evidence of nodal disease at the lower end of the trachea, a more thorough cleanout of the superior mediastinum may be achieved by splitting the sternum or removing the manubrium and one or more clavicular heads.

Extended Neck Dissection

Any of the neck dissections described previously may be extended to remove either lymph node groups or vascular, neural, or muscular structures that are not routinely removed in a neck dissection. A neck dissection may be extended to remove the retropharyngeal lymph nodes on one or both sides when the primary tumor originates in the pharyngeal walls. Ballantyne45 found a 44% incidence of retropharyngeal node involvement in a group of patients with carcinomas of the pharyngeal wall who were treated surgically. Tumors of the base of the tongue, the tonsil, the soft palate, and the retromolar trigone may also spread to these lymph nodes when they involve the lateral or posterior walls of the oropharynx. Adequate removal of a metastatic tumor in the neck may dictate the need to extend a neck dissection to resect structures such as the hypoglossal nerve, levator scapulae muscle, or carotid artery.

Controversy still exists about the advisability of resecting the common or the ICA (Fig. 121-17). Some surgeons believe that it is not justified to resect these arteries in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract because of the associated morbidity and because the prognosis of patients with disease in the neck that is extensive enough to warrant such a resection is dismal.46 For example, Moore and Baker47 observed a mortality rate of 30% and a cerebral complication rate of 45% among patients who underwent carotid ligation; it should be noted that these figures included elective and emergency ligation. In a study of 28 patients who had tumors grossly excised by “peeling” them off of the carotid artery, Kennedy and colleagues48 found that only 18% developed a recurrence in the neck without distant metastases; this observation led the authors to state that only this small group of patients may have benefitted from carotid resection. Goffinet and colleagues49 reported encouraging results for patients with large cervical metastases attached to the carotid artery who were by the resection of the tumor and intraoperative iodine125 seed suture implants over the remaining carotid artery. Tumor control was obtained in the neck in 77% of the patients, although only 15% of them were alive and free of disease after 1 year. There are surgeons who advocate resecting the common artery or the ICA when the extent of disease dictates it; they believe that current methods of assessing the adequacy of cerebral circulation on the basis of the contralateral carotid system allow for better preoperative patient selection.50–52 These beliefs—coupled with improved techniques for vascular and soft-tissue reconstruction—have made it possible to resect the carotid artery with acceptable morbidity. McCready and colleagues53 reported their observations in 16 patients who underwent carotid artery resection for the management of advanced carcinomas of the head and neck. Only two patients (12%) developed postoperative cerebrovascular complications, and seven patients (45%) were free of disease at 1 year. Others have reported similar results.50,52 Patients with frank involvement of the carotid wall whose preoperative examination indicates intolerance of carotid ligation should have carotid resection and reconstruction. Saphenous vein grafts are preferred over prosthetic grafts for reconstruction, and, if the skin has been heavily radiated or a portion of the skin over the carotid is resected, a myocutaneous flap should be used to cover the graft.54,55

Figure 121-17. Extended radical neck dissection, with resection of the common carotid artery.

(Redrawn from art provided courtesy of Douglas Denys, MD.)

If carotid artery resection is considered preoperatively, then endovascular balloon occlusion of the ICA with physiologic assessment will strongly predict the potential for stroke and the need for revascularization.56,57 An angiogram is performed, and an intravascular balloon placed in the ICA. The patient is heparinized, and the balloon is inflated to occlude the ICA. A second catheter in the contralateral carotid artery is used for an intracranial angiogram to assess the patency of collateral flow through the circle of Willis to the hemisphere in jeopardy. The demonstration of an excellent crossover flow through a patent anterior communicating artery, along with symmetric venous filling bilaterally, is predictive of a low probability of stroke if the ICA is sacrificed, and there is no indication for revascularization. If the angiogram is questionable, then occlusion may be maintained for 30 minutes, hypotension induced, and the patient observed clinically. Alternatively, a functional cerebral blood flow study such as intra-arterial xenon, xenon inhalation computed tomography scan, or single-photon emission computed tomography scan can be performed to assess functional cerebral blood flow to the hemisphere in jeopardy. If studies suggest that the patient will not tolerate ICA sacrifice, then consideration should be given to surgery designed to salvage the ICA, or a revascularization procedure should be employed.

Revascularization procedures may be within the bed of the tumor resection if proximal and distal ends of the carotid artery and ICA remain. Artificial versus saphenous vein interposition grafts can be used, depending on previous or future radiation therapy and wound infection potential. ICA revascularization procedures continue to be practiced in select neurosurgical cases, particularly in those involving extracranial to intracranial bypass grafting, with good results seen at select centers.56,57

Results of Neck Dissection

Radical Neck Dissection

Obviously the best results reported for patients undergoing radical neck dissection are those in whom the presence of histologically positive metastatic disease is not evident. In this scenario, 3% to 7% of patients will have disease recur in the ipsilateral neck.58 When radical neck dissection is used as a therapeutic procedure, there is a range of regional control rates. An appropriate analysis of results should, therefore, involve the consideration of several factors related to the degree of nodal involvement and whether the primary tumor remains under control.

The presence of extracapsular spread is an important prognostic factor with regard to recurrence in the neck after neck dissection.59,60 In addition, the degree of extracapsular involvement is also important. For example, Carter and colleagues46 reported a 44% recurrence rate for macroscopic extracapsular spread versus a 25% rate for microscopic extracapsular spread. In addition, the number of lymph nodes involved by tumor has also been found to correlate with the rate of recurrence. Patients with four or more involved nodes had a dramatically worse 4-year survival rate than patients with only one involved node.61 Strong also reported that the level of nodal involvement had prognostic importance, observing a recurrence rate in the neck of 36.5% in patients with positive nodes in one level versus 71% in patients with positive nodes in multiple levels.62 Remember that the use of adjuvant radiotherapy is considered by most to improve the rate of control in the neck after neck dissection.58,63

Modified Radical Neck Dissection

The rate of recurrence in the neck after modified radical neck dissection depends on the amount of disease to which the procedure was applied. When used as an elective procedure for patients with clinically N0 disease, the rate of recurrence varies between 4% and 7%. However, when this procedure is used therapeutically for patients with clinically positive disease, the recurrence rate in the dissected neck varies between 0% and 20%. In some of these reports, preoperative or postoperative radiation was also used. These results indicate that, in selected patients, modified radical neck dissection is an attractive alternative to radical neck dissection.16,58

Selective Neck Dissection

Data indicating the effectiveness of SND for the control of regional metastases related to upper aerodigestive tract carcinoma are available. For supraomohyoid neck dissection, Byers16 reported a regional recurrence rate of 5.8% for 154 patients with pathologic N0 disease, 24 of whom received postoperative radiotherapy. The rate of regional disease control for 80 patients with pathologic positive nodal disease was 15%; 62 of these patients had multiple positive nodes, and 61% had postoperative radiotherapy. In a later review of the MD Anderson experience, Medina and Byers51 found the recurrence rate to be 5% among patients with pathologic N0 disease, 10% when a single nodal metastases without extracapsular spread was found, and 24% when multiple positive nodes or extracapsular spread was found. Postoperative radiotherapy decreased the recurrence rate to 15% in the group with multiple nodes or extracapsular spread.

For patients undergoing lateral neck dissection, Byers16 reported a regional recurrence rate of 3.9% among 256 patients with pathologic N0 disease, 126 of whom received postoperative radiotherapy. Among the 41 patients with pathologic positive nodal disease, 37 of whom had postoperative radiotherapy, 7.3% had regional recurrences.

The data indicating relatively low regional recurrence rates for patients with clinical N0 neck disease support the effectiveness of SND procedures for patients with upper aerodigestive tract carcinoma. Of greater controversy is whether the procedures are effective for patients with node-positive disease. Pelliteri and colleagues64 found the regional recurrence rate for patients with pathologic positive nodal disease to be 11.1% among 27 patients undergoing a supraomohyoid neck dissection and 4.8% among 21 patients who had a lateral neck dissection. These results, along with those reported by Byers16 and Medina and Byers,51 indicate that the SND is feasible for a defined subset of patients with positive nodal disease. Postoperative radiotherapy is recommended for patients with multiple nodal disease or extracapsular spread. More recently, the efficacy of SND for clinically positive neck disease has been demonstrated by others.65–67 In 2002 Andersen and colleagues68 reported a 10-year, multi-institutional, retrospective review of pooled data from 106 previously untreated clinically and pathologically node-positive patients undergoing 129 SNDs and followed for a minimum of 2 years or until patient death. Overall, nine patients experienced disease recurrence in the neck, for a regional control rate of 94.3%. Six of these recurrences were in the areas of the neck that had been dissected during the SND. The authors concluded that these results support the use of SND in carefully selected patients with clinically positive nodal metastasis from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Regional control rates comparable with those achieved with the radical and modified radical neck dissections could be achieved in appropriately selected patients. The main advantages of the use of SND are that surgical time is shortened and morbidity—especially with regard to shoulder dysfunction—is decreased.

Among patients previously treated with radiotherapy or other types of neck surgery, most surgeons prefer to perform neck dissections that encompass all five neck levels when salvage surgery is feasible. However, emerging data support the use of SND as part of the planned treatment for patients with bulky neck disease whose primary tumor and regional nodes were initially treated with definitive radiation therapy or chemoradiation.69,70 Nigauri and colleagues71 failed to find evidence of skip metastases outside of levels II and III among 217 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx who were treated with radiation therapy. These authors recommended SND for patients with N1 disease, whereas modified radical neck dissection or radical neck dissection was recommended for patients with N2 or N3 disease. Boyd and colleagues72 analyzed 25 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, and supraglottic larynx who had been treated with radiation therapy. Among the 28 necks dissected (all but one patient had N2 or N3 disease), only one had a tumor outside of levels II through IV. On the basis of this, SND was recommended for patients with disease in all pharyngeal sites who required salvage or planned neck surgery after radiation therapy. Efficacy of targeted chemoradiation and planned SND to control bulk nodal disease in advanced neck cancer has been reported by Robbins and colleagues.73 In addition, Clayman and colleagues74 have used SND after chemoradiotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer in patients with advanced nodal disease. Thus it may be that, in the future, SND will play a more definitive role in the overall management of patients with initial bulky neck node disease with head and neck cancer that has been treated with nonsurgical modalities; however, further evidence is necessary.

Lymphoscintigraphy-Directed Neck Dissection

A potentially powerful adjunct to surgical treatment of the neck is lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. This technique, which was pioneered by Morton and colleagues7 for use in detecting the lymphatic spread of cutaneous melanoma, capitalizes on the ability of nuclear radiography to identify primary, secondary, and tertiary echelons of lymphatic drainage basins and to identify the index or “sentinel” lymph node associated with primary regions within the head and neck. It is minimally invasive, and it possesses the capacity to accurately stage the clinically occult neck in a number of different neoplasms.75 Linking this diagnostic and staging modality to lymphadenectomy or other elective treatment of the neck in mucosal carcinomas represents an attractive concept that has recently been explored by Pitman and colleagues76 at the University of Pittsburgh. These investigators examined the feasibility of identifying the sentinel lymph node in primary echelons of drainage from known primary neoplasms through lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, thus enabling one to stage the N0 neck in a minimally invasive manner and to direct elective neck therapy accordingly. On the basis of findings with both N0 and N+ patients, the investigators thought that lymphoscintigraphy and lymphatic mapping would offer the ability to stage neck disease and provide information about the presence of atypical basins of lymphatic flow from upper aerodigestive tract primary sites that would not typically be addressed by the more classic anatomic regions outlined for SND. Accordingly, patients undergoing this procedure would have lymphatic flow patterns uniquely defined according to neck anatomy and the effects of previous treatment. In addition, findings from the study suggested that lymphoscintigraphy in the N+ or previously treated neck demonstrated the potential for defining unpredictable cervical nodal levels at risk for metastasis. Studies such as this indicate that the use of lymphatic mapping for the treatment of HNSCC may ultimately provide the surgeon with the ability to adequately stage the N0 neck and direct elective therapy or assess the neck with recurrence in a minimally invasive manner to determine the extent of salvage required. The place of lymphatic mapping for avoiding a neck dissection remains inadequately defined at this time in terms of therapeutic efficacy, practical application, and health-related quality of life. Lymphatic mapping in HNSCC is probably best considered an investigational technique; as such, it has not yet achieved the status of “standard of care” for the treatment of head and neck carcinoma patients.77

Sequelae of Neck Dissection

For the past few years, it has been debated in the literature whether there is a major difference in postoperative shoulder dysfunction after a radical neck dissection that preserves the spinal accessory nerve. Using patient questionnaires, Schuller and colleagues78 compared symptomatology and the ability to return to preoperative employment of patients who underwent either a radical neck dissection or a modified radical neck dissection. Although they found no statistically significant difference between the two groups, Sterns and Shaheen79 and others using similar methods found that the majority of patients who had a nerve-sparing procedure did not have postoperative pain or shoulder dysfunction.80,81

Only recently have objective data about shoulder dysfunction after neck dissection been gathered prospectively. Leipzig and colleagues82 studied 109 patients who had undergone various types of neck dissections using preoperative and postoperative observations of shoulder movement made by the surgeons who rated the degree of shoulder dysfunction. The researchers concluded that any type of neck dissection may result in an impairment of function of the shoulder. They also noted that dysfunction occurred more frequently among those patients in whom the spinal accessory nerve was extensively dissected or resected.

In 1985 Sobol and colleagues55 performed a prospective study in which preoperative and postoperative measures of shoulder range of motion were compared. In addition, postoperative electromyograms (EMGs) were obtained in some patients. Shoulder range of motion was better in patients who underwent a nerve-sparing procedure than in patients who had a radical neck dissection. In addition, the type of nerve-sparing procedure was found to have an influence on the degree of shoulder disability. Patients who had undergone a modified radical neck dissection, in which the entire length of the nerve was dissected, had no dramatic difference in shoulder range of motion as compared with those patients who had a radical neck dissection 16 weeks after surgery. Patients who underwent a supraomohyoid neck dissection, in which there was less-extensive dissection of the spinal accessory nerve, performed significantly better (P > .05) than either of the other groups in terms of shoulder range of motion and EMG findings for the trapezius muscle. Interestingly, 16 weeks after surgery, moderate to severe EMG abnormalities were noted in up to 65% of the patients in whom the spinal accessory nerve was dissected along its entire length (i.e., modified radical neck dissection). Although no severe abnormalities were noted in the group undergoing supraomohyoid neck dissection, 22% of these patients showed moderate abnormalities. Several patients from each group had repeat studies at approximately 1 year after surgery. Unlike patients who had a radical neck dissection, patients in whom the nerve was spared showed evidence of improvement in all parameters studied.

A prospective study by Remmler and colleagues83 revealed that patients who had a nerve-sparing procedure had a serious but temporary spinal accessory nerve dysfunction. In this study, preoperative strength, range-of-motion measures, and EMG of the trapezius muscle were compared with postoperative measures obtained at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. The groups studied consisted of patients undergoing nerve-sparing procedures and those who had the nerve resected. Most of the patients in the nerve-sparing group had supraomohyoid neck dissections. Patients who underwent radical neck dissections had a major decrease in trapezius muscle strength on EMG at 1 month; these parameters did not improve with time. Interestingly, patients in the nerve-sparing group had a small but significant reduction in trapezius muscle strength and evidence of trapezius muscle denervation at 1 and 3 months, which improved by 12 months. More recently, Kuntz and Weymuller84 reported reduced quality-of-life scores among patients after neck dissection, with the worst scores being associated with radical neck dissection and the best scores with SND.

Hence the evidence indicates that even procedures involving minimal dissection of the spinal accessory nerve may result in shoulder dysfunction.84 It is only appropriate, therefore, to make every effort to avoid undue stretch or trauma to the nerve when a nerve-sparing procedure is performed. In addition, it is imperative that every patient who undergoes a neck dissection be questioned about the function of the shoulder and be examined by a physical therapist early during the postoperative period. If any deficit is detected, the patient should be properly counseled and coached to ensure proper rehabilitation of the shoulder.

Complications of Neck Dissection

In addition to the various medical complications that may occur after any surgical procedure in the head and neck region, a number of surgical complications may be related solely or in part to the neck dissection. If the course of a patient who has undergone a neck dissection as part of the surgical treatment of cancer of the head and neck region is followed, several complications may arise. When a neck dissection is done after radiotherapy of more than 70 Gy, there might be a higher risk of complications.48 However, adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy may not increase the complication rate.17

Chylous Fistula

In a 1990 review of 823 neck dissections performed by the surgeons at Memorial Hospital in New York City that included the removal of the lymph nodes in level IV, Spiro and colleagues63 found that 14 patients (1.9%) developed a chyle fistula. In this and other studies,85 a chylous leakage was identified and apparently controlled intraoperatively in the majority of patients who developed the complication. These observations remind the surgeon to not only avoid injury to the thoracic duct proper but also to ligate or clip any visualized or potential lymphatic tributaries in the area of the thoracic duct. This may be accomplished with relative ease if the operative field is kept bloodless when dissecting in this area of the neck. In addition, as soon as the dissection of this area is completed and again before closing the wound, the area should be observed for 20 or 30 seconds while the anesthesiologist increases the intrathoracic pressure; even the smallest leak of chylous material should be pursued until it is arrested. Indiscriminate clamping and ligating may be difficult and sometimes counterproductive because of the fragility of the lymphatic vessels and the surrounding fatty tissue. Hemoclips are ideal to control a source of leakage that is clearly visualized; otherwise it is preferable to use suture ligatures with pliable material, such as no. 5-0 silk, which are tied over a piece of hemostatic sponge to avoid tearing.

Facial/Cerebral Edema

The development of cerebral edema may be at the root of the impaired neurologic function and even coma that may occur after bilateral radical neck dissection. Ligation of the internal jugular veins leads to increased intracranial pressure.86,87 It has been shown experimentally that the increased cerebral venous pressure that occurs as a result of ligating both internal jugular veins in dogs is associated with inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.88 It may then be speculated that the resulting expansion of extracellular fluids and dilutional hyponatremia aggravate the cerebral edema and create a vicious cycle. In practice, these observations behoove the surgeon and the anesthesiologist to curtail the administration of fluids during and after bilateral radical neck dissections.89 In addition, perioperative management of fluid and electrolytes in these patients should not be guided solely by their urine output but rather by the monitoring of central venous pressure, cardiac output, and serum and urine osmolarity.

Blindness