CHAPTER 28 Neck

The neck extends from the base of the cranium and the inferior border of the mandible to the thoracic inlet.

SKIN

Cutaneous vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

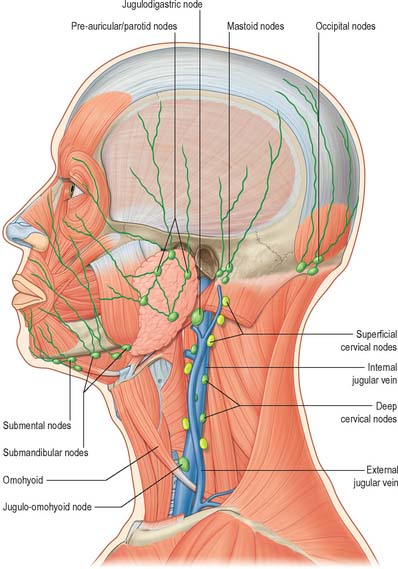

Many lymphatic vessels draining the superficial cervical tissues skirt the borders of sternocleidomastoid to reach the superior or inferior deep cervical nodes. Some pass over sternocleidomastoid and the posterior triangle to drain into the superficial cervical and occipital nodes (see Fig. 28.15). Lymph from the superior region of the anterior triangle drains to the submandibular and submental nodes. Vessels from the anterior cervical skin inferior to the hyoid bone pass to the anterior cervical lymph nodes near the anterior jugular veins, and their efferents go to the deep cervical nodes of both sides, including the infrahyoid, prelaryngeal and pretracheal groups. An anterior cervical node often occupies the suprasternal space.

Cutaneous innervation

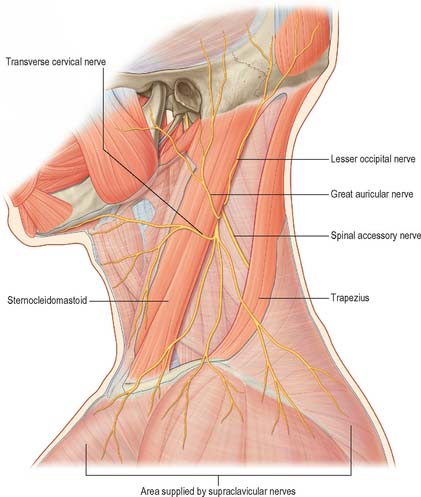

The cervical skin is innervated by branches of cervical spinal nerves, via both dorsal and ventral rami (see Fig. 43.6). The dorsal rami supply skin over the back of the neck and scalp, and the ventral rami supply skin covering the lateral and anterior portions of the neck, and the angle of the mandible (Fig. 28.1). The dorsal rami of the first, sixth, seventh and eighth cervical nerves have no cutaneous distribution in the neck. The greater occipital nerve mainly supplies the scalp; it comes from the medial branch of the dorsal ramus of the second cervical nerve. The medial branches of the dorsal rami of the third, fourth and fifth cervical nerves pierce trapezius to supply skin over the back of the neck sequentially. The ventral rami of the second, third and fourth cervical nerves supply named cutaneous branches (the lesser occipital, great auricular, transverse cutaneous and supraclavicular nerves), via the cervical plexus (Fig. 28.1) (see p. 456 for details of the motor branches of the cervical plexus).

Great auricular nerve

The great auricular nerve is the largest ascending branch of the cervical plexus. It arises from the second and third cervical rami, encircles the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid, perforates the deep fascia and ascends on the muscle beneath platysma with the external jugular vein. On reaching the parotid gland, it divides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch is distributed to the facial skin over the parotid gland and connects in the gland with the facial nerve. This cross innervation between somatic sensory supply (great auricular) and parasympathetic secretomotor fibres to the parotid is considered to be part of the anatomical basis for the phenomenon of gustatory sweating (Frey’s syndrome) seen after parotid surgery, when the nerve is at risk of injury. The posterior branch supplies the skin over the mastoid process and on the back of the auricle (except its upper part); a filament pierces the auricle to reach the lateral surface where it is distributed to the lobule and concha. The posterior branch communicates with the lesser occipital nerve, the auricular branch of the vagus and the posterior auricular branch of the facial nerve.

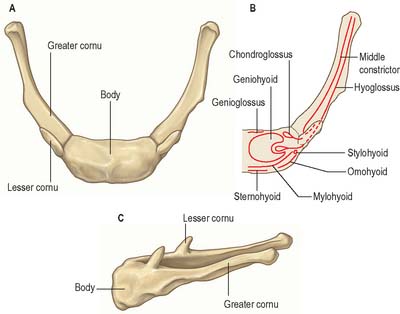

BONES, JOINTS AND CARTILAGES

The bones and cartilages of the neck are the cervical vertebrae and the hyoid bone, and the cartilages of the upper respiratory tract, including the larynx. The cervical vertebrae, occipital bone and the atlantooccipital and atlanto-axial joints are described in Chapter 42, and the laryngeal cartilages are described in Chapter 34.

TRIANGLES OF THE NECK

Anterolaterally the neck appears as a somewhat quadrilateral area, limited superiorly by the base of the mandible and a line continued from the angle of the mandible to the mastoid process, inferiorly by the upper border of the clavicle, anteriorly by the anterior median line, and posteriorly by the anterior margin of trapezius. This quadrilateral area can be further divided into anterior and posterior triangles by sternocleidomastoid, which passes obliquely from the sternum and clavicle to the mastoid process and occipital bone (Fig. 28.3). It is true that these triangles and their subdivisions are somewhat arbitrary, because many major structures – arteries, veins, lymphatics, nerves, and some viscera – transgress their boundaries without interruption, nevertheless they have a topographical value in description. Moreover, some of their subdivisions are easily identified by inspection and palpation and provide invaluable assistance in surface anatomical and clinical examination.

Fig. 28.3 The anterior and posterior triangles of the neck, left lateral aspect. See note in caption for Fig. 28.1

(Adapted from Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

ANTERIOR TRIANGLE OF THE NECK

The anterior triangle of the neck is bounded anteriorly by the median line of the neck and posteriorly by the anterior margin of sternocleidomastoid. Its base is the inferior border of the mandible and its projection to the mastoid process, and its apex is at the manubrium sterni. It can be subdivided into suprahyoid and infrahyoid areas above and below the hyoid bone, and into digastric, submental, muscular and carotid triangles by the passage of digastric and omohyoid across the anterior triangle (see Fig. 28.5).

Submental triangle

The single submental triangle is demarcated by the anterior bellies of both digastric muscles. Its apex is at the chin, its base is the body of the hyoid bone and its floor is formed by both mylohyoid muscles. It contains lymph nodes and small veins that unite to form the anterior jugular vein. The structures within the digastric and submental triangles are described in more detail with the floor of the mouth (on p. 501).

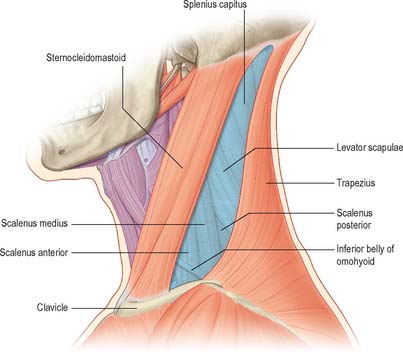

POSTERIOR TRIANGLE OF THE NECK

The posterior triangle is delimited anteriorly by the posterior edge of sternocleidomastoid, posteriorly by the anterior edge of trapezius, and inferiorly by the middle third of the clavicle (Fig. 28.3). Its apex is between the attachments of sternocleidomastoid and trapezius to the occiput and is often blunted, so that the ‘triangle’ becomes quadrilateral. The roof of the posterior triangle is formed by the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia. The floor of the triangle is formed by the prevertebral fascia overlying splenius capitis, levator scapulae and the scalene muscles. It is crossed, approximately 2.5 cm above the clavicle, by the inferior belly of omohyoid, which subdivides it into occipital and supraclavicular triangles. The contents of the posterior triangle include fat, lymph nodes (level V – see later), spinal accessory nerve, cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus, inferior belly of omohyoid, branches of the thyrocervical trunk (transverse cervical and suprascapular arteries), the third part of the subclavian artery, and the external jugular vein. The anterior and lateral groups of prevertebral muscles form the floor of the posterior triangle.

Occipital triangle

The occipital triangle constitutes the upper and larger part of the posterior triangle, with which it shares the same borders, except that inferiorly it is limited by the inferior belly of omohyoid. Its floor, from above down, is formed by splenius capitis, levator scapulae, and scaleni medius and posterior; semispinalis capitis occasionally appears at the apex. The triangle is covered by skin, superficial and deep fasciae and inferiorly by platysma. The spinal accessory nerve pierces sternocleidomastoid and crosses levator scapulae obliquely downwards and backwards to reach the deep surface of trapezius. The surface marking of its course is in a line from the junction of the superior one-third and inferior two-thirds of sternocleidomastoid, to the junction of the inferior one-third and superior two-thirds of trapezius. Cutaneous and muscular branches of the cervical plexus emerge at the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid. Inferiorly, supraclavicular nerves, transverse cervical vessels and the uppermost part of the brachial plexus cross the triangle. Lymph nodes lie along the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid from the mastoid process to the root of the neck.

CERVICAL FASCIA

SUPERFICIAL CERVICAL FASCIA

The superficial cervical fascia is usually a thin lamina covering platysma and is hardly demonstrable as a separate layer. It may, however, contain considerable amounts of adipose tissue, especially in females. Like all superficial fascia it is not a separate stratum, but merely a zone of loose connective tissue between dermis and deep fascia, and is joined to both. In the lower cervical region, aponeurotic fibres of platysma gradually fan out in the superficial fascia: they either become skin ligaments or continue into the fascia covering pectoralis major and deltoid. These aponeurotic fibres cover the anterior and lateral cervical regions and often mimic the investing layer of deep cervical fascia, forming a tissue barrier (Nash et al 2005).

DEEP CERVICAL FASCIA

Descriptions of the organization of the deep cervical fascia are largely based on the classic work of Grodinsky & Holyoke in 1938. However recent anatomical studies using techniques such as sheet plastination and confocal microscopy have indicated that the arrangement of the deep cervical fascia is more complicated than was previously thought (Zhang & Lee 2002, Nash et al 2005) (Fig. 28.4).

Tissue spaces and the spread of infection and injectate

The fascial layers of the neck define a number of potential tissue ‘spaces’ above and below the hyoid bone. In health, the tissues within these spaces are closely applied to each other or are filled with relatively loose connective tissue. However, infections arising superiorly, such as dental, tonsillar, vertebral or intervertebral disc-related infections, can alter these relationships. The organisms responsible are often betahaemolytic streptococci or a variety of anaerobes. Streptococci produce proteolytic enzymes which digest the loose connective tissue and so open up the tissue spaces. Since there are no tissue barriers running horizontally in the neck, infections which are not treated promptly can rapidly spread from the infratemporal fossa down to the mediastinum below (see Ch. 55), cross the midline through the sublingual and submental spaces and even track into the axilla.

Understanding the configuration of the cervical fasciae and spaces is essential for the placement of local anaesthetic cervical plexus blocks in the neck to facilitate operations such as thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy and carotid endarterectomy (Pandit et al 2000). For example, injection of local anaesthetic either in the superficial fascial plane or under the investing fascia of the posterior triangle can provide a similarly effective cervical plexus block (Pandit et al 2003), presumably because the investing fascia between sternocleidomastoid and trapezius is not a well-defined fascial sheet and is indistinguishable from the surrounding loose connective tissue (Zhang & Lee 2002).

The tissue spaces above the hyoid bone are the submandibular and submental spaces beneath the inferior border of the mandible; the pharyngeal spaces; and the prevertebral space near the base of the skull. These spaces are described on pages 524 and 568. Tissue spaces around the larynx are described on page 584.

Radiologically, the portion of the pretracheal space between the strap fascia and the fascia of the thyroid gland is referred as the anterior cervical space. The posterolateral border of the space is the carotid sheath or the fascia of sternocleidomastoid. The anterior cervical space often provides a symmetric landmark on transverse imaging (Smoker & Harnsberger 1991).

In general, cellulitis around the jaw is only likely to develop when the tissues are infected by virulent and invasive organisms at a point where there is access to the fascial spaces: the predisposing causes do not often coincide, and cellulitis is therefore uncommon. Cellulitis in the region of the maxilla is even more uncommon, but fascial space infections may develop in various sites as the result of infected local anaesthetic needles. Since there are no barriers running horizontally with respect to the tissue spaces in the neck, infection entering in this site can rapidly spread more or less unhindered down the neck and may enter the mediastinum (see Ch. 55).

All forms of cellulitides of the neck or deep neck space infections are potentially serious. Narrowing of the upper airway can occur as a result of inflammation and oedema, leading to dyspnoea or obstruction of the upper airway (with stridor) and reduced oxygenation of the lungs. This situation can be extremely difficult to manage by conventional techniques. The increased rigidity and reduced compliance of the tissues mean that manoeuvres such as manual anterior jaw thrust or laryngoscopy may fail to re-open the airway. Specialized techniques, e.g. flexible fibreoptic-assisted tracheal intubation or surgical tracheostomy under local anaesthesia, may be required to provide general anaesthesia to facilitate the surgical drainage and treatment of the cellulitis or deep space abscess.

MUSCLES

The muscles that form part of the musculoskeletal column in the neck are described in Chapter 42. They can be considered in three groups, anterior, lateral and posterior; very broadly speaking, the muscles in these groups lie anterior, lateral or posterior to the cervical vertebrae. The anterior and lateral groups include longi colli and capitis; recti capitis anterior and lateralis; scaleni anterior, medius, posterior and minimi (when present). The posterior muscle group is composed of the cervical components of the intrinsic muscles of the back, overlaid by some of the extrinsic ‘immigrant’ muscles of the back that run between the upper limb and the axial skeleton (trapezius, levator scapulae, see Ch. 42). The intrinsic muscles are arranged in superficial and deep layers. The superficial layer contains splenius capitis and cervicis. The deeper layers include the transversospinal group (semispinales cervicis and capitis, multifidus and rotatores cervicis), interspinales and intertransversarii, and the suboccipital group (recti capitis posterior major and minor and obliquus capitis superior and inferior).

The muscles associated with the pharynx and larynx are described in Chapters 33 and 34 respectively.

Sternocleidomastoid

Sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 28.5) descends obliquely across the side of the neck and forms a prominent surface landmark, especially when contracted. It is thick and narrow centrally, and broader and thinner at each end. The muscle is attached inferiorly by two heads. The medial or sternal head is rounded and tendinous, arises from the upper part of the anterior surface of the manubrium and sterni and ascends posterolaterally. The lateral or clavicular head, which is variable in width and contains muscular and fibrous elements, ascends almost vertically from the superior surface of the medial third of the clavicle. The two heads are separated near their attachments by a triangular interval which corresponds to a surface depression, the lesser supraclavicular fossa. As they ascend, the clavicular head spirals behind the sternal head and blends with its deep surface below the middle of the neck, forming a thick, rounded belly. Sternocleidomastoid inserts superiorly by a strong tendon into the lateral surface of the mastoid process from its apex to its superior border, and by a thin aponeurosis into the lateral half of the superior nuchal line. The clavicular fibres are directed mainly to the mastoid process; the sternal fibres are more oblique and superficial, and extend to the occiput. The direction of pull of the two heads is therefore different, and the muscle may be classed as ‘cruciate’ and slightly ‘spiralized’.

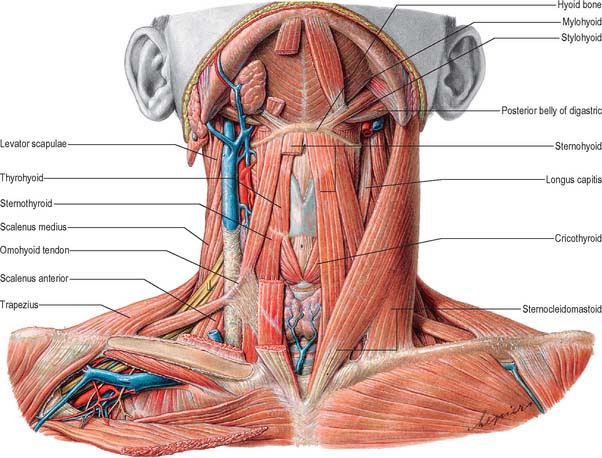

MUSCLES OF THE ANTERIOR TRIANGLE OF THE NECK

Apart from the superficial neck muscles already described, the anterior triangle contains two of the suprahyoid muscles, namely digastric and stylohyoid, and the four infrahyoid strap muscles (Fig. 28.5). The other suprahyoid muscles, namely mylohyoid and geniohyoid, are described with the floor of the mouth on page 501.

Digastric

Digastric has two bellies and lies below the mandible, extending from the mastoid process to the chin (Fig. 28.5). The posterior belly, which is longer than the anterior, is attached in the mastoid notch of the temporal bone, and passes downwards and forwards. The anterior belly is attached to the digastric fossa on the base of the mandible near the midline, and slopes downwards and backwards. The two bellies meet in an intermediate tendon which perforates stylohyoid and runs in a fibrous sling attached to the body and greater cornu of the hyoid bone and is sometimes lined by a synovial sheath. The two bellies of digastric mark out the borders of the submandibular triangle.

Stylohyoid

Stylohyoid arises by a small tendon from the posterior surface of the styloid process, near its base. Passing downwards and forwards, it inserts into the body of the hyoid bone at its junction with the greater cornu (and just above the attachment of the superior belly of omohyoid). It is perforated near its insertion by the intermediate tendon of digastric (Fig. 28.5). The muscle may be absent or double. It may lie medial to the external carotid artery and may end in the suprahyoid or infrahyoid muscles.

Stylohyoid ligament

The stylohyoid ligament is a fibrous cord extending from the tip of the styloid process to the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone. It gives attachment to the highest fibres of the middle pharyngeal constrictor and is intimately related to the lateral wall of the oropharynx. Below, it is overlapped by hyoglossus. The ligament is derived from the cartilage of the second branchial arch, and may be partially calcified.

INFRAHYOID MUSCLES

The infrahyoid muscles are organized so that sternohyoid and omohyoid lie superficially and sternothyroid and thyrohyoid lie more deeply (Fig. 28.5). The muscles are involved in movements of the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage during vocalization, swallowing and mastication and are mainly innervated from the ansa cervicalis.

Sternohyoid

Sternohyoid is a thin, narrow strap muscle that arises from the posterior surface of the medial end of the clavicle, the posterior sternoclavicular ligament and the upper posterior aspect of the manubrium (Fig. 28.5). It ascends medially and is attached to the inferior border of the body of the hyoid bone. Inferiorly, there is a considerable gap between the muscle and its contralateral fellow, but the two usually come together in the middle of their course, and are contiguous above this. Sternohyoid may be absent or double, augmented by a clavicular slip (cleidohyoid), or interrupted by a tendinous intersection.

Omohyoid

Omohyoid consists of two bellies united at an angle by an intermediate tendon (Fig. 28.5). The inferior belly is a flat, narrow band, which inclines forwards and slightly upwards across the lower part of the neck. It arises from the upper border of the scapula, near the scapular notch, and occasionally from the superior transverse scapular ligament. It then passes behind sternocleidomastoid and ends there in the intermediate tendon. The superior belly begins at the intermediate tendon, passes almost vertically upwards near the lateral border of sternohyoid and is attached to the lower border of the body of the hyoid bone lateral to the insertion of sternohyoid. The length and form of the intermediate tendon varies, although it usually lies adjacent to the internal jugular vein at the level of the arch of the cricoid cartilage. The angulated course of the muscle is maintained by a band of deep cervical fascia, attached below to the clavicle and the first rib, which ensheathes the tendon. A variable amount of skeletal muscle may be present in the fascial band; either belly may be absent or double; the inferior belly may be attached directly to the clavicle and the superior is sometimes fused with sternohyoid.

Sternothyroid

Sternothyroid is shorter and wider than sternohyoid, and lies deep and partly medial to it (Fig. 28.5). It arises from the posterior surface of the manubrium sterni inferior to the origin of sternohyoid and from the posterior edge of the cartilage of the first rib. It is attached above to the oblique line on the lamina of the thyroid cartilage, where it delineates the upward extent of the thyroid gland. In the lower part of the neck the muscle is in contact with its contralateral fellow, but the two diverge as they ascend.

Thyrohyoid

Thyrohyoid is a small, quadrilateral muscle that may be regarded as an upward continuation of sternothyroid (Fig. 28.5). It arises from the oblique line on the lamina of the thyroid cartilage, and passes upwards to attach to the lower border of the greater cornu and adjacent part of the body of the hyoid bone.

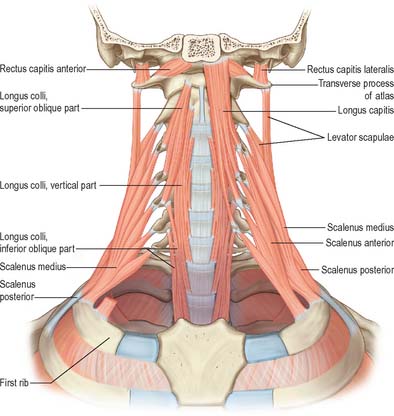

ANTERIOR VERTEBRAL MUSCLES

The anterior vertebral group of muscles are longi colli and capitis, and recti capitis anterior and lateralis (Fig. 28.6), all of which are flexors of the head and neck to varying degrees. Together with the lateral vertebral muscles they form the prevertebral muscle group.

Longus capitis

Longus capitis (Fig. 28.6) has a narrow origin from tendinous slips from the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae and becomes broad and thick above, where it is inserted into the inferior surface of the basilar part of the occipital bone.

Longus colli

Longus colli (Fig. 28.6) is applied to the anterior surface of the vertebral column, between the atlas and the third thoracic vertebra. It can be divided into three parts which all arise by tendinous slips. The inferior oblique part is the smallest, running upwards and laterally from the fronts of the bodies of the first two or three thoracic vertebrae to the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae. The superior oblique part passes upwards and medially from the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the third, fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae to be attached by a narrow tendon to the anterolateral surface of the tubercle on the anterior arch of the atlas. The vertical intermediate part ascends from the fronts of the bodies of the upper three thoracic and lower three cervical vertebrae to the fronts of the bodies of the second, third and fourth cervical vertebrae.

LATERAL VERTEBRAL MUSCLES

Scaleni anterior, medius and posterior extend obliquely between the upper two ribs and the cervical transverse processes. Scalenus minimus (pleuralis) is associated with the suprapleural membrane and cervical pleura, and is described in Chapter 57.

Scalenus anterior

Scalenus anterior lies at the side of the neck deep (posteromedial) to sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 28.5; see also Fig. 28.18). Above, it is attached by musculotendinous fascicles to the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the third, fourth, fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae. These converge, blend and descend almost vertically, to be attached by a narrow, flat tendon to the scalene tubercle on the inner border of the first rib, and to a ridge on the upper surface of the rib anterior to the groove for the subclavian artery.

Scalenus medius

Scalenus medius, the largest and longest of the scaleni, is attached above to the transverse process of the axis and the front of the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the lower five cervical vertebrae (Fig. 28.6). It frequently extends upwards to the transverse process of the atlas. Below it is attached to the upper surface of the first rib between the tubercle of the rib and the groove for the subclavian artery.

The anterolateral surface of the muscle is related to sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 28.5). It is crossed anteriorly by the clavicle and omohyoid, and it is separated from scalenus anterior by the subclavian artery and ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves. Levator scapulae and scalenus posterior lie posterolateral to it. The upper two roots of the nerve to serratus anterior and the dorsal scapular nerve (to the rhomboids) pierce the muscle and appear on its lateral surface.

Scalenus posterior

Scalenus posterior is the smallest and most deeply situated of the scalene muscles (Fig. 28.6). It passes from the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of the fourth, fifth, and sixth cervical vertebrae to the outer surface of the second rib, behind the tubercle for serratus anterior, where it is attached by a thin tendon.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

ARTERIES OF THE NECK

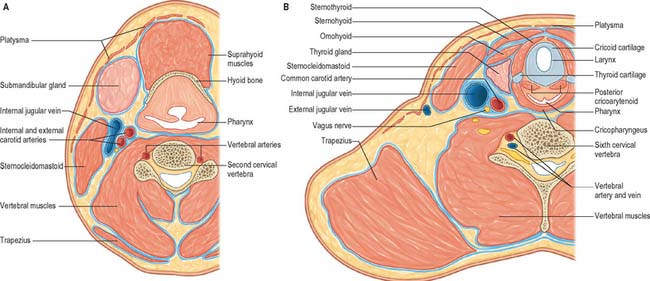

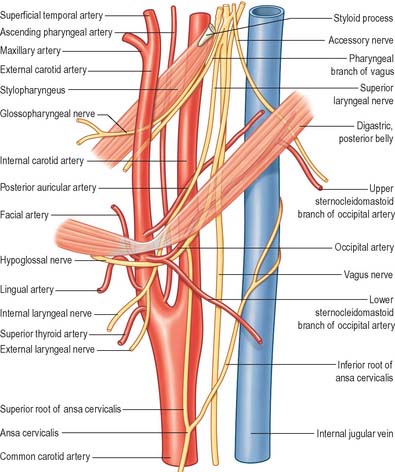

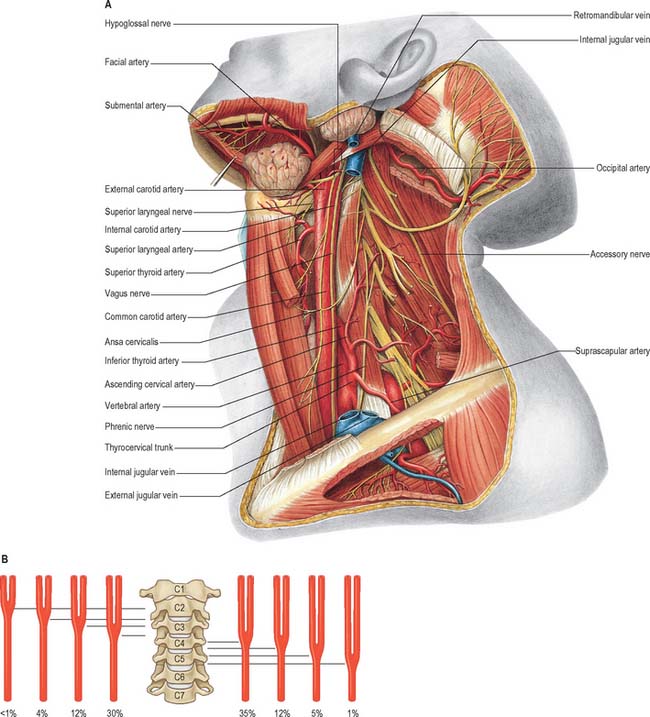

The common carotid, internal carotid, and external carotid arteries provide the major source of blood to the head and neck (Figs 28.7A, 28.8). Additional arteries arise from branches of the subclavian artery, particularly the vertebral artery.

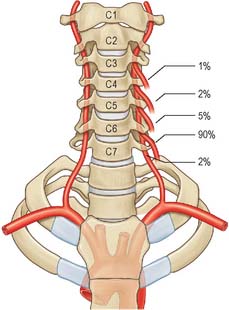

Fig. 28.7 A, Vessels and nerves of the neck, left lateral view: sternocleidomastoid and the greater part of omohyoid and the internal jugular vein have been removed. Compare with Fig. 28.17, which shows a deeper level of dissection. B, Variation in levels of bifurcation of the common carotid artery, related to the cervical vertebrae.

(A, From Sobotta 2006.) (Redrawn with permission from Sobatta 2006.)

External carotid artery

The external carotid artery (Figs 28.7A, 28.8) begins lateral to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage, level with the intervertebral disc between the third and fourth cervical vertebrae. A little curved and with a gentle spiral, it first ascends slightly forwards and then inclines backwards and a little laterally, to pass midway between the tip of the mastoid process and the angle of the mandible. Here, in the substance of the parotid gland behind the neck of the mandible, it divides into its terminal branches, the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries. As it ascends, it gives off several large branches, and diminishes rapidly in calibre. In children the external carotid is smaller than the internal carotid, but in adults the two are of almost equal size. At its origin, it is in the carotid triangle and lies anteromedial to the internal carotid artery. It later becomes anterior, then lateral, to the internal carotid as it ascends. At mandibular levels the styloid process and its attached structures intervene between the vessels: the internal carotid is deep, and the external carotid superficial, to the styloid process. A fingertip placed in the carotid triangle perceives a powerful arterial pulsation, which represents the termination of the common carotid, the origins of external and internal carotids and the stems of the initial branches of the external carotid.

Superior thyroid artery

The superior thyroid artery is the first branch of the external carotid artery, and arises from the anterior surface of the external carotid just below the level of the greater cornu of the hyoid bone (Figs 28.7A, 28.8). It descends along the lateral border of thyrohyoid to reach the apex of the lobe of the thyroid gland. Lying medially are the inferior constrictor muscle and the external laryngeal nerve: the nerve is often posteromedial, and therefore at risk when the artery is being ligatured. Occasionally it may issue directly from the common carotid.

Branches

The superior thyroid artery supplies the thyroid gland and some adjacent skin. Glandular branches are: anterior, which runs along the medial side of the upper pole of the lateral lobe to supply mainly the anterior surface; a branch which crosses above the isthmus to anastomose with its fellow of the opposite side; and posterior, which descends on the posterior border to supply the medial and lateral surfaces and anastomoses with the inferior thyroid artery. Sometimes a lateral branch supplies the lateral surface. The artery also has the following named branches: infrahyoid, superior laryngeal, sternocleidomastoid and cricothyroid.

Lingual artery

The lingual artery provides the chief blood supply to the tongue and the floor of the mouth (Fig. 28.8; see Ch. 30). It arises anteromedially from the external carotid artery opposite the tip of the greater cornu of the hyoid bone, between the superior thyroid and facial arteries. It often arises with the facial or, less often, with the superior thyroid artery. It may be replaced by a ramus of the maxillary artery. Ascending medially at first, it loops down and forwards, passes medial to the posterior border of hyoglossus and then runs horizontally forwards deep to it. The lingual artery next ascends again almost vertically, and courses sinuously forwards on the inferior surface of the tongue as far as its tip. The further course of the lingual artery is described on page 505.

Facial artery

The facial artery (Figs 28.7, 28.8; see Figs 29.13, 29.18) arises anteriorly from the external carotid in the carotid triangle, above the lingual artery and immediately above the greater cornu of the hyoid bone. In the neck, at its origin, it is covered only by the skin, platysma, fasciae and often by the hypoglossal nerve. It runs up and forwards, deep to digastric and stylohyoid. At first on the middle pharyngeal constrictor, it may reach the lateral surface of styloglossus, separated there from the palatine tonsil only by this muscle and the lingual fibres of the superior constrictor. Medial to the mandibular ramus it arches upwards and grooves the posterior aspect of the submandibular gland. It then turns down and descends to the lower border of the mandible in a lateral groove on the submandibular gland, between the gland and medial pterygoid. Reaching the surface of the mandible, the facial artery curves round its inferior border, anterior to masseter, to enter the face: its further course is described on page 490. The artery is very sinuous throughout its extent. In the neck this may be so that the artery is able to adapt to the movements of the pharynx during deglutition, and similarly on the face, so that the artery can adapt to movements of the mandible, lips and cheeks. Facial artery pulsation is most palpable where the artery crosses the mandibular base, and again near the corner of the mouth. Its branches in the neck are the ascending palatine, tonsillar, submental and glandular arteries.

The submental artery is the largest cervical branch of the facial artery (Fig. 28.7). It arises as the facial artery separates from the submandibular gland and turns forwards on mylohyoid below the mandible. It supplies the overlying skin and muscles, and anastomoses with a sublingual branch of the lingual and mylohyoid branch of the inferior alveolar artery. At the chin it ascends over the mandible, and divides into superficial and deep branches, which anastomose with the inferior labial and mental arteries to supply the chin and lower lip.

Occipital artery

The occipital artery arises posteriorly from the external carotid artery, approximately 2 cm from its origin (Figs 28.7A, 28.8). At its origin, the artery is crossed superficially by the hypoglossal nerve, which winds round it from behind. The artery next passes backwards, up and deep to the posterior belly of digastric, and crosses the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, hypoglossal, vagus and accessory nerves. Between the transverse process of the atlas and the mastoid process, the occipital artery reaches the lateral border of rectus capitis lateralis. It then runs in the occipital groove of the temporal bone, medial to the mastoid process and attachments of sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis, longissimus capitis and digastric, and lies successively on rectus capitis lateralis, obliquus superior and semispinalis capitis. Finally, accompanied by the greater occipital nerve, it turns upwards to pierce the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia connecting the cranial attachments of trapezius and sternocleidomastoid, and ascends tortuously in the dense superficial fascia of the scalp where it divides into many branches.

Posterior auricular artery

The posterior auricular artery is a small vessel which branches posteriorly from the external carotid just above digastric and stylohyoid. It ascends between the parotid gland and the styloid process to the groove between the auricular cartilage and mastoid process, and divides into auricular and occipital branches which are described with the face on page 491. In the neck, it provides branches to supply digastric, stylohyoid, sternocleidomastoid and the parotid gland. It also gives origin to the stylomastoid artery – described as an indirect branch of the posterior auricular artery in about a third of subjects – which enters the stylomastoid foramen to supply the facial nerve, tympanic cavity, mastoid antrum air cells and semicircular canals. In the young, its posterior tympanic ramus forms a circular anastomosis with the anterior tympanic branch of the maxillary artery.

Internal carotid artery

The internal carotid artery supplies most of the ipsilateral cerebral hemisphere, eye and accessory organs, forehead and, in part, the nose. From its origin at the carotid bifurcation (Fig. 28.8) (where it usually has a carotid sinus), it ascends in front of the transverse processes of the upper three cervical vertebrae to the inferior aperture of the carotid canal in the petrous part of the temporal bone. Here it enters the cranial cavity and turns anteriorly through the cavernous sinus in the carotid groove on the side of the body of the sphenoid bone. It terminates below the anterior perforated substance by division into the anterior and middle cerebral arteries. It may be divided conveniently into cervical, petrous, cavernous and cerebral parts.

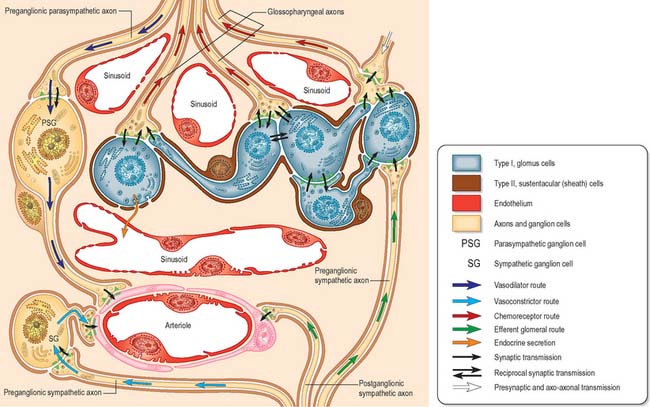

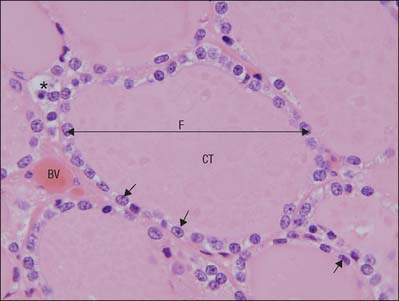

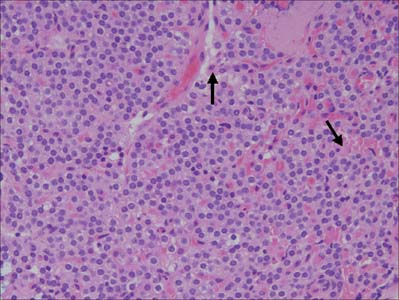

Carotid sinus and carotid body

The carotid body is surrounded by a fibrous capsule from which septa divide the enclosed tissue into lobules. Each lobule contains glomus (type I) cells which are separated from an extensive network of fenestrated sinusoids by sustentacular (type II) cells (Fig. 28.9). Glomus cells store a number of peptides, particularly enkephalins, bombesin and neurotensin, and amines including dopamine, serotonin, adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and are therefore regarded as paraneurones. Unmyelinated axons lie in a collagenous matrix between the sustentacular cells and the sinusoidal endothelium, and many synapse on the glomus cells. They are visceral afferents which travel in the carotid sinus nerve to join the glossopharyngeal nerve. Preganglionic sympathetic axons and fibres from the carotid sinus synapse on parasympathetic and sympathetic ganglion cells, which lie either in isolation or in small groups near the surface of each carotid body. Postganglionic axons travel to local blood vessels: the parasympathetic efferent fibres are probably vasodilatory and the sympathetic ones are vasoconstrictor.

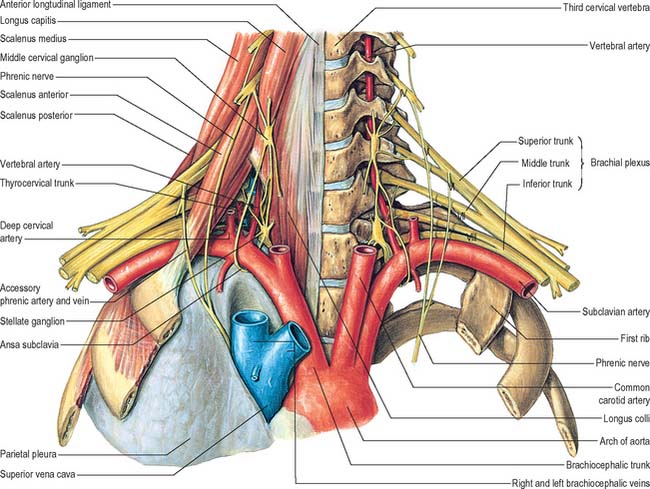

Subclavian artery

The right subclavian artery arises from the brachiocephalic trunk, the left from the aortic arch (see Figs 28.14, 28.18). For description, each is divided into a first part, from its origin to the medial border of scalenus anterior, a second part behind this muscle and a third part from the lateral margin of scalenus anterior to the outer border of the first rib, where the artery becomes the axillary artery. Each subclavian artery arches over the cervical pleura and pulmonary apex. Their first parts differ, whereas the second and third parts are almost identical.

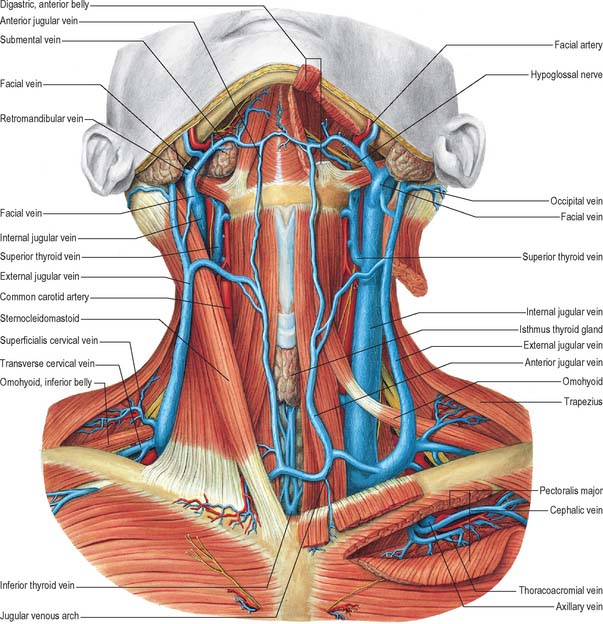

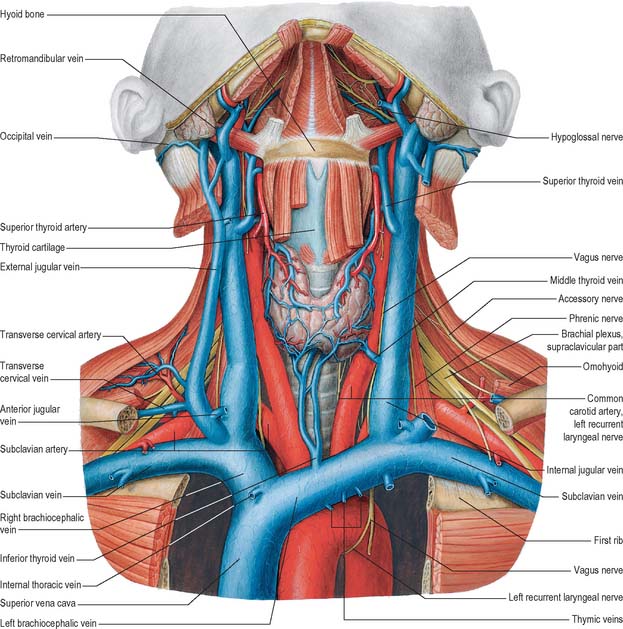

Fig. 28.14 The veins of the neck, seen from the front and at a deeper level than Fig. 28.13. Both sternocleidomastoids have been removed and additional dissection has exposed the thyroid gland and some of the structures that pass through the upper thoracic aperture.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Parts of the subclavian arteries

Second part of subclavian artery

The second part of the subclavian artery lies behind scalenus anterior; it is short and the highest part of the vessel (see Fig. 28.18).

Third part of subclavian artery

The right subclavian artery may arise above or below sternoclavicular level; it may be a separate aortic branch and be the first or last branch of the arch. When it is the first branch, it is in the position of a brachiocephalic trunk. When it is the last branch, it arises from the left end of the arch, and ascends obliquely to the right behind the trachea, oesophagus and right common carotid to the first rib. When this occurs, the right recurrent laryngeal nerve hooks round the common carotid artery. Sometimes, when the right subclavian artery is the last aortic branch, it passes between the trachea and oesophagus and can cause dysphagia, a condition known as dysphagia lusoria. It may perforate scalenus anterior, and very rarely may pass anterior to it. Sometimes the subclavian vein accompanies the artery behind scalenus anterior. The artery may ascend as high as 4 cm above the clavicle or it may reach only its upper border. The left subclavian artery is occasionally combined at its origin with the left common carotid artery.

Vertebral artery

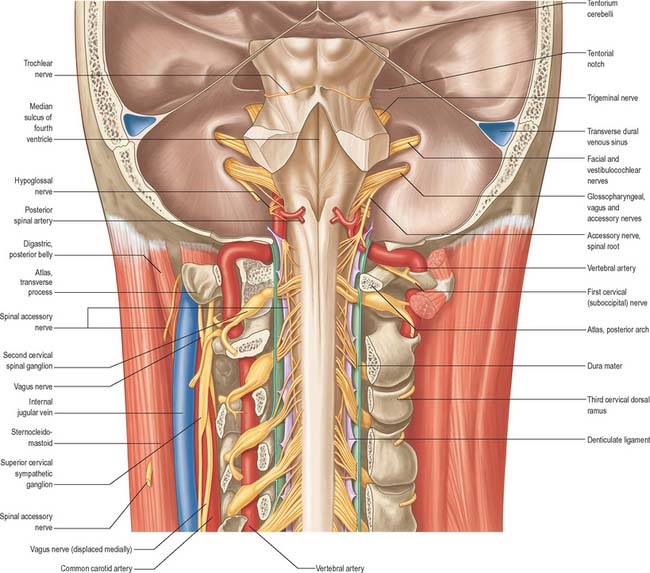

The vertebral artery arises from the superoposterior aspect of the first part of the subclavian artery. It passes through the foramina in the transverse processes of all of the cervical vertebrae except the seventh, curves medially behind the lateral mass of the atlas and enters the cranium via the foramen magnum (Fig. 28.11). At the lower pontine border it joins its fellow to form the basilar artery. Occasionally it may enter the cervical vertebral column via the fourth, fifth or seventh cervical vertebra (Fig. 28.10).

The first part passes back and upwards between longus colli and scalenus anterior, behind the common carotid artery and the vertebral vein. It is crossed by the inferior thyroid artery, and by the thoracic duct on the left side and the right lymphatic duct on the right side. The seventh cervical transverse process, the inferior cervical ganglion and ventral rami of the seventh and eighth cervical spinal nerves lie posterior to the artery. The second part ascends through the transverse foramina of the remaining cervical vertebrae, accompanied by a large branch from the inferior cervical ganglion and a plexus of veins which form the vertebral vein low in the neck. It lies anterior to the ventral rami of the cervical spinal nerves (C.2–C.6), and ascends almost vertically to pass through the transverse process of the axis, where it turns laterally to gain access to the transverse foramen of the atlas (Fig. 28.11). The third part issues medial to rectus capitis lateralis, and curves backwards and medially behind the lateral mass of the atlas, with the first cervical ventral spinal ramus lying on its medial side. In this position it lies in a groove on the upper surface of the posterior arch of the atlas, and it enters the vertebral canal below the inferior border of the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane. This part of the artery, covered by semispinalis capitis, lies in the suboccipital triangle. The first cervical dorsal spinal ramus separates the artery from the posterior arch. The fourth part pierces the dura and arachnoid mater, and ascends anterior to the hypoglossal roots. It inclines anterior to the medulla oblongata and unites with its contralateral fellow to form the midline basilar artery at the lower border of the pons.

Thyrocervical trunk

Inferior thyroid artery

The inferior thyroid artery loops upwards anterior to the medial border of the scalenus anterior, turns medially just below the sixth cervical transverse process, then descends on longus colli to the lower border of the thyroid gland (Figs 28.7A, 28.17). It passes anterior to the vertebral vessels and posterior to the carotid sheath and its contents (and usually the sympathetic trunk, whose middle cervical ganglion frequently adjoins the vessel). On the left, near its origin, the artery is crossed anteriorly by the thoracic duct as the latter curves inferolaterally to its termination. Relations between the terminal branches of the artery and recurrent laryngeal nerve are very variable and of considerable surgical importance. The artery usually passes behind the nerve as it nears the gland. However, very close to the gland, the right nerve is equally likely to be anterior, posterior or amongst, the branches of the artery, and the left nerve is usually posterior. The artery is not accompanied by the inferior thyroid vein.

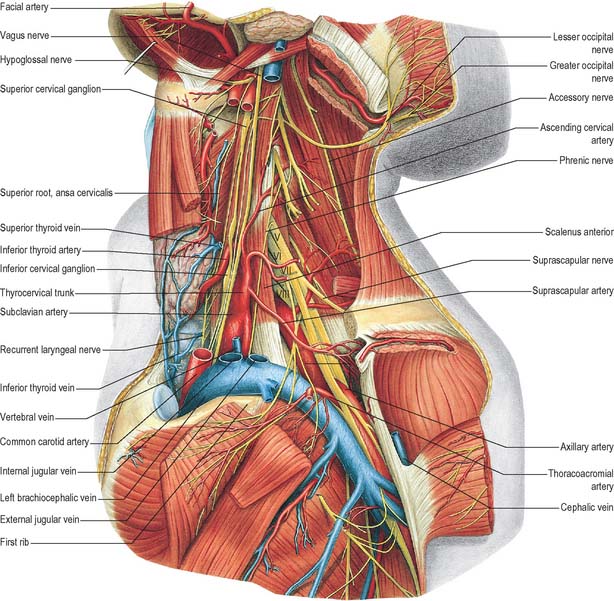

Fig. 28.17 Vessels and nerves of the neck, left lateral view. The left sternocleidomastoid, the greater part of the infrahyoid group of muscles and numerous vessels have been removed in order to expose deeper structures. Compare with Fig. 28.7A, which shows a more superficial level of dissection. V, VI, VII, VIII refer to the anterior primary rami of C5, C6, C7, and C8, respectively.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Suprascapular artery

The suprascapular artery descends laterally across scalenus anterior and the phrenic nerve, posterior to the internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid (Fig. 28.7A). It then crosses anterior to the subclavian artery and brachial plexus, posterior to, and parallel with, the clavicle, subclavius and the inferior belly of omohyoid, to reach the superior scapular border.

Superficial cervical artery

The superficial cervical artery is given off at a higher level than the suprascapular artery. It crosses anterior to the phrenic nerve, scalenus anterior and the brachial plexus and is covered by the internal jugular vein, sternocleidomastoid and platysma. It crosses the floor of the posterior triangle to reach the anterior margin of levator scapulae, and ascends deep to the anterior part of the trapezius, which it supplies, together with the adjoining muscles and the cervical lymph nodes. It anastomoses with the superficial ramus of the descending branch of the occipital artery. About a third of the superficial cervical and dorsal scapular arteries arise in common from the thyrocervical trunk, with a superficial (superficial cervical artery) and a deep (dorsal scapular artery) branch (see Figs 25.1, 25.2 and 46.26). The latter passes laterally anterior to the brachial plexus and then posterior to levator scapulae.

Costocervical trunk

Deep cervical artery

The deep cervical artery usually arises from the costocervical trunk (see Fig. 25.1). It is analogous in its first segment to a posterior branch of a posterior intercostal artery, and occasionally is a separate branch of the subclavian artery. It passes back above the eighth cervical spinal nerve between the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra and the neck of the first rib (sometimes between the transverse processes of the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae). It then ascends between semispinales capitis and cervicis to the level of the second cervical vertebra. It supplies adjacent muscles and anastomoses with the deep branch of the descending branch of the occipital artery and branches of the vertebral artery. A spinal branch enters the vertebral canal between the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae.

VEINS OF THE NECK

Veins in the neck show considerable variation. They are superficial or deep to the deep fascia but are not entirely separate systems. Superficial veins are tributaries, some with specific names, given below, of the anterior, external and posterior jugular veins (Figs 28.13, 28.14). They drain a much smaller volume of tissue than the deep veins. The latter drain all but the subcutaneous structures, mostly into the internal jugular vein and also into the subclavian vein.

External jugular vein

The external jugular vein mainly drains the scalp and face, although it also drains some deeper parts. The vein is formed by the union of the posterior division of the retromandibular vein with the posterior auricular vein and begins near the mandibular angle just below or in the parotid gland (see Fig. 25.3). It descends from the angle to the midclavicle, running obliquely, superficial to sternocleidomastoid, to the root of the neck. Here it crosses the deep fascia and ends in the subclavian vein, lateral or anterior to scalenus anterior. There are valves at its entrance into the subclavian, but they do not prevent regurgitation. Its wall is adherent to the rim of the fascial opening. It is covered by platysma, superficial fascia and skin, and is separated from sternocleidomastoid by deep cervical fascia. The vein crosses the transverse cutaneous nerve and lies parallel with the great auricular nerve, posterior to its upper half. In size the external jugular vein is inversely proportional to the other veins in the neck, and may be double. Between the entrance into the subclavian vein and a point approximately 4 cm above the clavicle, the vein is often dilated, producing a so-called sinus.

Internal jugular vein

The internal jugular vein collects blood from the skull, brain, superficial parts of face and much of the neck. It begins at the cranial base in the posterior compartment of the jugular foramen, where it is continuous with the sigmoid sinus. At its origin it is dilated as the superior bulb, which lies below the posterior part of the tympanic floor. The internal jugular vein descends in the carotid sheath, and unites with the subclavian vein, posterior to the sternal end of the clavicle, to form the brachiocephalic vein (Fig. 28.14). Near its termination the vein dilates into the inferior bulb, above which is a pair of valves.

Facial vein

The initial part of the facial vein as it lies on the face is described on page 492. From the face it passes over the surface of masseter, crosses the body of the mandible and enters the neck where it runs obliquely back under platysma. Here it lies superficial to the submandibular gland, digastric and stylohyoid (Fig. 28.14). Just anteroinferior to the mandibular angle it is joined by the anterior division of the retromandibular vein, and then descends superficial to the loop of the lingual artery, the hypoglossal nerve and external and internal carotid arteries, to enter the internal jugular near the greater cornu of the hyoid bone, i.e. in the upper angle of the carotid triangle. Near its end a large branch often descends along the anterior border of sternocleidomastoid to the anterior jugular vein. Its uppermost segment, above its junction with the superior labial vein, is often termed the angular vein.

Superior thyroid vein

The superior thyroid vein is formed by deep and superficial tributaries corresponding to the arterial branches in the upper part of the thyroid gland (Figs 28.13, 28.14). It accompanies the superior thyroid artery, receives the superior laryngeal and cricothyroid veins, and ends in the internal jugular or facial vein.

Subclavian vein

The subclavian vein is a continuation of the axillary vein and extends from the outer border of the first rib to the medial border of scalenus anterior, where it joins the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic vein (Fig. 28.14). The clavicle and subclavius lie anterior to it, the subclavian artery is posterosuperior, separated by scalenus anterior and the phrenic nerve, and the first rib and pleura are inferior. The vein usually has a pair of valves 2 cm from its end. Its tributaries are the external jugular, dorsal scapular and sometimes the anterior jugular vein. At its junction with the internal jugular, the left subclavian vein receives the thoracic duct, and the right subclavian vein receives the right lymphatic duct.

CERVICAL GROUPS OF LYMPH NODES

Lymph nodes in the head and neck are distributed in terminal and outlying groups (Fig. 28.15; see Fig. 25.5). The terminal group is related to the carotid sheath and the nodes it contains are the deep cervical lymph nodes. All lymph vessels of the head and neck drain into this group, either directly from tissues or indirectly through nodes in the outlying groups. Efferents of the deep cervical nodes form the jugular trunk. The right jugular trunk collects lymph from the right arm and right half of the thorax and the right head and neck and may end in the jugulosubclavian junction or the right lymphatic duct. The left jugular trunk usually enters the thoracic duct, but it may join the internal jugular or subclavian vein.

Spread of malignant disease in the neck

Cancers arising in the head and neck from regions such as the thyroid gland, larynx, oral cavity and oropharynx, nasopharynx and paranasal sinuses have predictable patterns of spread through the chains of lymph nodes in the neck. When operating on malignant disease in this region it is vitally important to understand these patterns of spread so that for any individual cancer the appropriate operation is undertaken. Clinical experience has shown that the lymph nodes in the neck fall into five distinct groups (see Fig. 25.5). Level I nodes lie in the submandibular triangle bounded by the anterior and posterior bellies of digastric and the lower border of the mandible above. Level II (upper jugular) nodes lie around the upper portion of the internal jugular vein and the upper part of the spinal accessory nerve. They extend from the skull base to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery or the hyoid bone. Level III (middle jugular) nodes lie around the middle third of the internal jugular vein from the inferior border of level II to the superior belly of omohyoid or cricothyroid membrane. Level IV (lower jugular) nodes lie around the lower third of the internal jugular vein from the inferior border of level III to the clavicle. The anterior and posterior borders for levels II, III and IV are the lateral border of sternohyoid and the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid respectively. Level V (posterior triangle) nodes lie around the lower part of the spinal accessory nerve and the transverse cervical vessels.

Knowing which levels of nodes are likely to be involved in the metastatic spread of a particular cancer arising in the head and neck means that appropriate nodal clearance can be undertaken. The classic radical neck dissection first described by Crile in 1906 involves a thorough clearance of levels I to V including the sacrifice of sternocleidomastoid, the internal jugular vein and the spinal accessory nerve. Modified radical neck dissections (so-called functional neck dissections) still remove level I to V nodes, but spare either or all of sternocleidomastoid, the internal jugular vein and the spinal accessory. Selective neck dissections remove selected groups of nodes, e.g. the supraomohyoid neck dissection removes level I to III nodes, the lateral neck dissection removes level II to IV nodes, and the posterolateral neck dissection removes level II to V nodes.

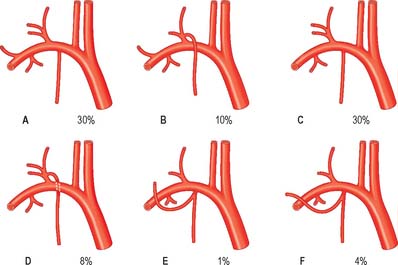

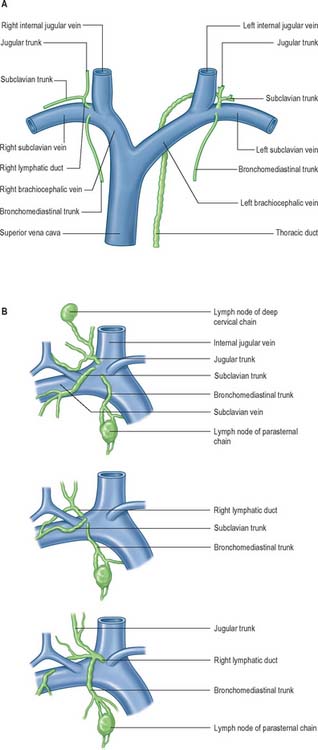

Cervical lymphovenous portals

Lymph is returned to the systemic venous circulation via right and left lymphovenous portals sited at, or near, the junctions of the internal jugular and subclavian veins (Fig. 28.16). The arrangement of these terminations is variable. Usually, three small lymph trunks converge towards their venous junctions on either side of the body, and they are joined, on the left side only, by the larger thoracic duct.

Fig. 28.16 A, The termination of the right lymphatic trunk and the thoracic duct.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.) B, Variations in the terminal lymphatic trunks nodes of the right side.

The three right lymphatic trunks usually open independently (Fig. 28.16B). Their orifices are clustered either on the ventral aspect of the jugulo/subclavian junction, or in the nearby wall of either of the great veins. Sometimes one or more of the trunks may bifurcate (or even trifurcate) preterminally and then terminate via multiple orifices. Rarely, the three trunks fuse to form a short, single, right lymphatic duct (about 1 cm long) that inclines across the medial border of scalenus anterior at the root of the neck to reach the ventral aspect of the venous junction, where its orifice is guarded by a bicuspid semilunar valve. An incomplete right lymphatic duct may be present if the subclavian and jugular trunks, or any combination of their terminals, are fused. When this occurs, the bronchomediastinal trunk almost invariably opens separately.

On the left, the four trunks that converge on the left lymphovenous portal are the left jugular and left subclavian trunks, which have a disposition corresponding to that of their counterparts on the right; the left bronchomediastinal trunk, which has a drainage similar to the right trunk, but which drains more of the heart – the ‘left’ and part of the ‘right’ hearts of clinical parlance – and more of the oesophagus; and the thoracic duct, which drains all of the rest of the body (Fig. 28.16A).

INNERVATION

CERVICAL VENTRAL RAMI

Cervical plexus

The cervical plexus is formed by the ventral rami of the upper four cervical nerves, and supplies some neck muscles and the diaphragm, and areas of skin on the head, neck and chest (Fig. 28.1). It is situated in the neck opposite a line drawn down the side of the neck from the root of the auricle to the level of the upper border of the thyroid cartilage. It lies deep to the internal jugular vein, the deep fascia and sternocleidomastoid, and anterior to scalenus medius and levator scapulae. Each ramus, except the first, divides into ascending and descending parts, which unite in communicating loops. From the first loop (C2 and 3) superficial branches supply the head and neck; cutaneous nerves of the shoulder and chest arise from the second loop (C3 and 4). Muscular and communicating branches arise from the same nerves. The branches are superficial or deep. The superficial branches perforate the cervical fascia to supply the skin while the deep branches in general supply muscles. The superficial branches either ascend (the lesser occipital, great auricular and the transverse cutaneous nerves) or descend (supraclavicular nerves). These nerves are described in detail in this chapter on page 435. The deep branches form medial and lateral series.

Deep branches – medial series

The superior root of the ansa cervicalis (descendens hypoglossi) (Figs 28.7A, 28.8) leaves the hypoglossal nerve where it curves round the occipital artery and then descends anterior to or in the carotid sheath. It contains only fibres from the first cervical spinal nerve. After giving a branch to the superior belly of omohyoid, it is joined by the inferior root of the ansa from the second and third cervical spinal nerves. The two roots form the ansa cervicalis (ansa hypoglossi), from which branches supply sternohyoid, sternothyroid and the inferior belly of omohyoid. Another branch is said to descend anterior to the vessels into the thorax to join the cardiac and phrenic nerves.

The inferior root of the ansa cervicalis (nervus descendens cervicalis) (Figs 28.7A, 28.8) is formed by the union of a branch from the second with another from the third cervical ramus. It descends on the lateral side of the internal jugular vein, crosses it a little below the middle of the neck, and continues forwards to join the superior root anterior to the common carotid artery, forming the ansa cervicalis (ansa hypoglossi), from which all infrahyoid muscles except thyrohyoid are supplied. The inferior root comes from the second and third cervical ventral rami in 75% cases, from the second to fourth in 15%, from the third alone in 5%. Occasionally it may be derived from either the second alone or from the first to third.

The phrenic nerve arises chiefly from the fourth cervical ventral ramus, but also has contributions from the third and fifth. It is formed at the upper part of the lateral border of scalenus anterior and descends almost vertically across its anterior surface behind the prevertebral fascia (Figs 28.7A, 28.17, 28.18). It descends posterior to sternocleidomastoid, the inferior belly of omohyoid (near its intermediate tendon), the internal jugular vein, transverse cervical and suprascapular arteries and, on the left, the thoracic duct. At the root of the neck, it runs anterior to the second part of the subclavian artery, from which it is separated by the scalenus anterior (some accounts state that on the left side the nerve passes anterior to the first part of the subclavian artery), and posterior to the subclavian vein. The phrenic nerve enters the thorax by crossing medially in front of the internal thoracic artery.

Brachial plexus

The brachial plexus is formed by the union of the ventral rami of the lower four cervical nerves and the greater part of the ventral ramus of the first thoracic ventral ramus. It may also receive contributions from the fourth cervical and second thoracic spinal nerves. As its name suggests, its branches supply the muscles, joints and skin of the upper limb. The relations and distribution of the brachial plexus are described in detail in Section 6. However, it is also mentioned here because, at its origin, the brachial plexus lies in the posterior triangle of the neck, in the angle between the clavicle and the lower posterior border of sternocleidomastoid. It emerges between the scaleni anterior and medius, superior to the third part of the subclavian artery, and is covered by platysma, deep fascia and skin, through which it is palpable (Fig. 28.17). It is crossed by the supraclavicular nerves, the nerve to subclavius, the inferior belly of omohyoid, the external jugular vein and the superficial ramus of the transverse cervical artery. The plexus passes posterior to the medial two-thirds of the clavicle, subclavius and the suprascapular vessels, and lies on the first digitation of serratus anterior and on subscapularis.

CERVICAL DORSAL RAMI

Each cervical spinal dorsal ramus except the first divides into medial and lateral branches, and all innervate muscles. In general, only medial branches of the second to fourth, and usually the fifth, supply skin. Except for the first (sometimes called the suboccipital nerve) and second, each dorsal ramus passes back medial to a posterior intertransverse muscle, curving round the articular process into the interval between semispinalis capitis and semispinalis cervicis. The cervical dorsal rami are described in detail on pages 755–756.

CRANIAL NERVES

Glossopharyngeal nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve (Figs 28.8, 28.11, 28.19) supplies motor fibres to stylopharyngeus, parasympathetic secretomotor fibres to the parotid gland (derived from the inferior salivatory nucleus), sensory fibres to the tympanic cavity, pharyngotympanic tube, fauces, tonsils, nasopharynx, uvula and posterior (postsulcal) third of the tongue, and gustatory fibres for the postsulcal part of the tongue.

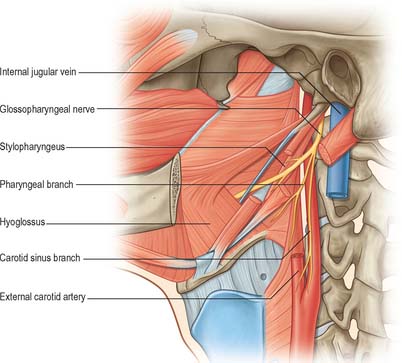

Fig. 28.19 Glossopharyngeal nerve in the anterior triangle of the neck.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

The nerve leaves the skull through the anteromedial part of the jugular foramen, anterior to the vagus and accessory nerves, and in a separate dural sheath. In the foramen it is lodged in a deep groove leading from the cochlear aqueductal depression, and is separated by the inferior petrosal sinus from the vagus and accessory nerves. The groove is bridged by fibrous tissue, which is calcified in 25% of skulls. After leaving the foramen, the nerve passes forwards between the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery and then descends anterior to the latter, deep to the styloid process and its attached muscles, to reach the posterior border of stylopharyngeus. It curves forwards on stylopharyngeus and either pierces the lower fibres of the superior pharyngeal constrictor or passes between it and the middle constrictor to be distributed to the tonsil, the mucosae of the pharynx and postsulcal part of the tongue, the vallate papillae, and oral mucous glands.

Vagus nerve

The vagus is a large mixed nerve. It has a more extensive course and distribution than any other cranial nerve, and runs through the neck, thorax and abdomen. Its central connections are described in Chapter 19.

The vagus exits the skull through the jugular foramen accompanied by the accessory nerve, with which it shares an arachnoid and a dural sheath. Both nerves lie anterior to a fibrous septum that separates them from the glossopharyngeal nerve. The vagus descends vertically in the neck in the carotid sheath, between the internal jugular vein and the internal carotid artery, to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage, and then passes between the vein and the common carotid artery to the root of the neck. Its relationships in this part of its course are therefore similar to those described for these structures (Figs 28.7A, 28.8, 28.17). Its further course differs on the two sides. The right vagus descends posterior to the internal jugular vein to cross the first part of the subclavian artery and enter the thorax. The left vagus enters the thorax between the left common carotid and subclavian arteries and behind the left brachiocephalic vein.

Inferior (nodose) ganglion

Both vagal ganglia are exclusively sensory, and contain somatic, special visceral and general visceral afferent neurones. The superior ganglion is chiefly somatic, and most of its neurones enter the auricular nerve, whilst neurones in the inferior ganglion are concerned with visceral sensation from the heart, larynx, lungs and the alimentary tract from the pharynx to the transverse colon. Some fibres transmit impulses from taste endings in the vallecula and epiglottis. Large afferent fibres are derived from muscle spindles in the laryngeal muscles. Vagal sensory neurones in the nodose ganglion may show some somatotopic organization. Both ganglia are traversed by parasympathetic, and perhaps some sympathetic fibres, but there is no evidence that vagal parasympathetic components relay in the inferior ganglion. Preganglionic motor fibres from the dorsal vagal nucleus and the special visceral efferents from the nucleus ambiguus, which descend to the inferior vagal ganglion, commonly form a visible band, skirting the ganglion in some mammals. These larger fibres probably provide motor innervation to the larynx in the recurrent laryngeal nerve, together with some contribution to the superior laryngeal nerve supplying cricothyroid.

Branches in the neck

The recurrent laryngeal nerve differs, in origin and course, on the two sides. On the right it arises from the vagus anterior to the first part of the subclavian artery, and curves backwards below and then behind it to ascend obliquely to the side of the trachea behind the common carotid artery. Near the lower pole of the lateral lobe of the thyroid gland it is closely related to the inferior thyroid artery, and crosses either in front of, behind, or between, its branches. On the left, the nerve arises from the vagus on the left of the aortic arch, curves below it immediately behind the attachment of the ligamentum arteriosum to the concavity of the aortic arch and ascends to the side of the trachea. As the recurrent laryngeal nerve curves round the subclavian artery, or the aortic arch, it gives cardiac filaments to the deep cardiac plexus. On both sides the recurrent laryngeal nerve ascends in or near a groove between the trachea and oesophagus. It is closely related to the medial surface of the thyroid gland before it passes under the lower border of the inferior constrictor, and it enters the larynx behind the articulation of the inferior thyroid cornu with the cricoid cartilage. The recurrent laryngeal nerve supplies all laryngeal muscles, except the cricothyroid, and it communicates with the internal laryngeal nerve, supplying sensory filaments to the laryngeal mucosa below the vocal folds. It also carries afferent fibres from laryngeal stretch receptors. The recurrent laryngeal nerve is described further with the larynx (p. 589).

Accessory nerve

The accessory nerve (Figs 28.7A, 28.11, 28.17) is conventionally described as a single entity, even though its two components, which join for a relatively short part of its course, are of quite separate origin.

Spinal root

The spinal root arises from an elongated nucleus of motor cells situated in the lateral aspect of the ventral horn which extends from the junction of the spinal cord and medulla to the sixth cervical segment (Fig. 28.11). Some rootlets emerge directly, others turn cranially before exiting. Their line of exit is irregular rather than linear, and the spinal root usually passes through the first cervical dorsal root ganglion. The rootlets form a trunk which ascends between the ligamentum denticulatum and the dorsal roots of the spinal nerves and enters the skull via the foramen magnum, behind the vertebral artery. It then turns upwards and passes laterally to reach the jugular foramen, which it traverses in a common dural sheath with the vagus, but separated from that nerve by a fold of arachnoid mater. As the spinal root exits the jugular foramen it runs posterolaterally and passes either medial or lateral to the internal jugular vein. Occasionally it passes through the vein. The nerve then crosses the transverse process of the atlas and is itself crossed by the occipital artery. It descends obliquely, medial to the styloid process, stylohyoid and the posterior belly of the digastric. Running with the superior sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery, it reaches the upper part of sternocleidomastoid and enters its deep surface, to form an anastomosis with fibres from C2 alone, C3 alone, or C2 and C3, the ansa of Maubrac. It may also communicate with the anterior root of the first cervical nerve (McKenzie branch).

The accessory nerve occasionally terminates in sternocleidomastoid. More commonly it emerges a little above the midpoint of the posterior border of sternocleidomastoid, generally above the emergence of the great auricular nerve (usually within 2 cm of it) and between 4–6 cm from the tip of the mastoid process. However, the point of emergence is very variable. The nerve then crosses the posterior triangle on levator scapulae (Fig. 28.7A), separated from it by the prevertebral layer of deep cervical fascia and adipose tissue. Here the nerve is relatively superficial and related to the superficial cervical lymph nodes. About 3–5 cm above the clavicle it passes behind the anterior border of trapezius, often dividing to form a plexus on its deep surface which receives contributions from C3 and C4, or C4 alone. It then enters the deep surface of the muscle.

Conventionally, the spinal root is thought to provide the sole motor supply to sternocleidomastoid, and the second and third cervical nerves are believed to carry proprioceptive fibres from it. The supranuclear pathway of fibres destined for sternocleidomastoid is not simple: fibres may undergo a double decussation in the brainstem and/or there may be a bilateral projection to the muscle from each hemisphere. The motor supply to the upper and middle portions of trapezius is primarily from the spinal accessory nerve. However, the lower two-thirds of the muscle, in 75% of subjects, receives an innervation from the cervical plexus. On the basis of the incomplete denervation of the muscle that sometimes occurs following sacrifice of both the accessory nerve and the cervical plexus, it has been suggested that the trapezius receives a partial motor supply from other sources, possibly via thoracic roots. In addition to their motor contribution, C3 and 4 carry proprioceptive fibres from trapezius. In 25% of subjects the spinal accessory nerve receives no fibres from the cervical plexus. (For a detailed review of the applied surgical anatomy of the spinal accessory nerve plexus, see Brown 2002.)

Sensory ganglia have been described along the course of the spinal root.

Hypoglossal nerve

The hypoglossal nerve is motor to all the muscles of the tongue, except palatoglossus. The hypoglossal rootlets run laterally behind the vertebral artery, collected into two bundles which perforate the dura mater separately opposite the hypoglossal canal in the occipital bone, and unite after traversing it. The canal is sometimes divided by a spicule of bone. The nerve emerges from the canal in a plane medial to the internal jugular vein, internal carotid artery, ninth, tenth and eleventh cranial nerves, and passes inferolaterally behind the internal carotid artery and glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves to the interval between the artery and the internal jugular vein (Fig. 28.8). Here it makes a half-spiral turn round the inferior vagal ganglion, and is united with it by connective tissue. It then descends almost vertically between the vessels and anterior to the vagus to a point level with the angle of the mandible, becoming superficial below the posterior belly of digastric and emerging between the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery. It loops round the inferior sternocleidomastoid branch of the occipital artery, crosses lateral to both internal and external carotid arteries and the loop of the lingual artery a little above the tip of the greater cornu of the hyoid, and is itself crossed by the facial vein (Figs 28.7A, 28.8, 28.17). Its course is described further on page 506.

Branches of distribution

The descending branch (descendens hypoglossi) contains fibres from the first cervical spinal nerve. It leaves the hypoglossal nerve when it curves around the occipital artery, and runs down on the carotid sheath. It provides a branch to the superior belly of omohyoid before joining with the descendens cervicalis to form the ansa cervicalis (Figs 28.7A, 28.8).

CERVICAL SYMPATHETIC TRUNK

The cervical sympathetic trunk lies on the prevertebral fascia behind the carotid sheath and contains three interconnected ganglia, the superior, middle and inferior (stellate or cervicothoracic) (Figs 28.17, 28.18). However there may occasionally be two or four ganglia. The cervical sympathetic ganglia send grey rami communicantes to all the cervical spinal nerves but receive no white rami communicantes from them. Their spinal preganglionic fibres emerge in the white rami communicantes of the upper five thoracic spinal nerves (mainly the upper three), and ascend in the sympathetic trunk to synapse in the cervical ganglia. In their course, the grey rami communicantes may pierce longus capitis or scalenus anterior.

Superior cervical ganglion

The superior cervical ganglion is the largest of the three ganglia (Fig. 28.17). It lies on the transverse processes of the second and third cervical vertebrae and is probably formed from four fused ganglia judging by its grey rami to C1–4. The internal carotid artery within the carotid sheath is anterior, and longus capitis is posterior. The lower end of the ganglion is united by a connecting trunk to the middle cervical ganglion. Postganglionic branches are distributed in the internal carotid nerve, which ascends with the internal carotid artery into the carotid canal to enter the cranial cavity, and in lateral, medial and anterior branches. They supply vasoconstrictor and sudomotor nerves to the face and neck, dilator pupillae and smooth muscle in the eyelids and orbitalis.

The lateral branches are grey rami communicantes to the upper four cervical spinal nerves and to some of the cranial nerves. Branches pass to the inferior vagal ganglion, the hypoglossal nerve, the superior jugular bulb and associated jugular glomus or glomera, and to the meninges in the posterior cranial fossa. Another branch, the jugular nerve, ascends to the cranial base and divides into two; one part joins the inferior glossopharyngeal ganglion and the other joins the superior vagal ganglion.

Middle cervical ganglion

The middle cervical ganglion is the smallest of the three, and is occasionally absent, in which case it may be replaced by minute ganglia in the sympathetic trunk or may be fused with the superior ganglion. It is usually found at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, anterior or just superior to the inferior thyroid artery, or it may adjoin the inferior cervical ganglion. It probably represents a coalescence of the ganglia of the fifth and sixth cervical segments, judging by its postganglionic rami, which join the fifth and sixth cervical spinal nerves (but sometimes also the fourth and seventh). It is connected to the inferior cervical ganglion by two or more very variable cords. The posterior cord usually splits to enclose the vertebral artery, while the anterior cord loops down anterior to, and then below, the first part of the subclavian artery, medial to the origin of its internal thoracic branch, and supplies rami to it. This loop is the ansa subclavia and is frequently multiple, lies closely in contact with the cervical pleura and typically connects with the phrenic nerve, and sometimes with the vagus (Fig. 28.18).

Inferior (or cervicothoracic/stellate) ganglion

The inferior cervical ganglion (cervicothoracic/stellate) is irregular in shape and much larger than the middle cervical ganglion (Fig. 28.18). It is probably formed by a fusion of the lower two cervical and first thoracic segmental ganglia, sometimes including the second and even third and fourth thoracic ganglia. The first thoracic ganglion may be separate, leaving an inferior cervical ganglion above it. The sympathetic trunk turns backwards at the junction of the neck and thorax and so the long axis of the cervicothoracic ganglion becomes almost anteroposterior. The ganglion lies on or just lateral to the lateral border of longus colli between the base of the seventh cervical transverse process and the neck of the first rib (which are both posterior to it). The vertebral vessels are anterior, and the ganglion is separated from the posterior aspect of the cervical pleura inferiorly by the suprapleural membrane. The costocervical trunk of the subclavian artery branches near the lower pole of the ganglion, and the superior intercostal artery is lateral.

Within the foramina transversaria and intertransverse spaces, the cervical grey rami communicantes form intersegmental arcades as they communicate with one another and the ventral rami of the upper five or six cervical spinal nerves. These arcades accompany the second part of the vertebral artery and create the appearance of a long nerve known as the vertebral nerve. Fine filaments from this nerve and the grey rami communicantes form the vertebral plexus on the surface of the vertebral artery. This plexus contains not only sympathetic efferent fibres but also somatic sensory fibres from the adventitia of the artery, whose cell bodies are located in the cervical dorsal root ganglia. The vertebral nerve sends filaments to the posterolateral corners of the cervical intervertebral discs (Bogduk et al 1988), and gives rise to the meningeal branches (sinuvertebral nerves) at each cervical segment. The vertebral plexus, which contains some neuronal cell bodies, continues into the skull along the vertebral and basilar arteries and their branches as far as the posterior cerebral artery, where it meets a plexus from the internal carotid artery. The plexus on the inferior thyroid artery reaches the thyroid gland, and connects with the recurrent and external laryngeal nerves, the cardiac branch of the superior cervical ganglion, and the common carotid plexus.

Horner’s syndrome

Any condition or injury that destroys the sympathetic trunk ascending from the thorax through the neck into the face results in Horner’s syndrome, characterized by a drooping eyelid (ptosis), sunken globe (enophthalmos), narrow palpebral fissure, contracted pupil (meiosis), vasodilatation and lack of thermal sweating (anhydrosis) on the affected side. This occurs classically when a bronchial carcinoma invades the sympathetic trunk. It also occurs as a complication of cervical sympathectomy or a radical neck dissection. Avulsion of the first thoracic nerve from the spinal cord may be diagnosed by development of the syndrome after closed traction lesion of the supraclavicular brachial plexus.

VISCERA

SUBMANDIBULAR SALIVARY GLAND

Each submandibular salivary gland is situated behind and below the ramus of the mandible, in the region of the submandibular triangle, between the anterior and posterior bellies of digastric (Fig. 28.7A). The gland is described in detail on page 520.

THYROID GLAND

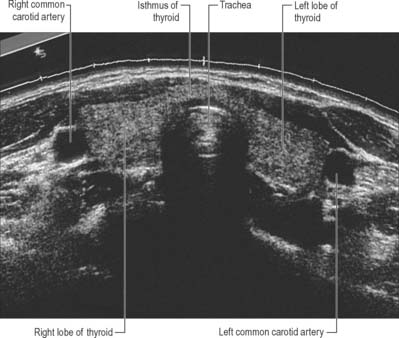

The thyroid gland, brownish-red and highly vascular, is placed anteriorly in the lower neck, level with the fifth cervical to the first thoracic vertebrae (Figs 28.4, 28.17). It is ensheathed by the pretracheal layer of deep cervical fascia and consists of right and left lobes connected by a narrow, median isthmus. It usually weighs 25 g, but this varies. The gland is slightly heavier in females, and enlarges during menstruation and pregnancy. Estimation of the size of the thyroid gland is clinically important in the evaluation and management of thyroid disorders and can be achieved non-invasively by means of diagnostic ultrasound. No significant difference in thyroid gland volume has been observed between males and females from 8 months to 15 years.

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Arteries

The thyroid gland is supplied by the superior and inferior thyroid arteries and sometimes by an arteria thyroidea ima from the brachiocephalic trunk or aortic arch (Figs 28.14, 28.17). The arteries are large and their branches anastomose frequently both on and in the gland, ipsilaterally and contralaterally. The superior thyroid artery, which is closely related to the external laryngeal nerve, pierces the thyroid fascia and then divides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch supplies the anterior surface of the gland, and the posterior branch supplies the lateral and medial surfaces. The inferior thyroid artery approaches the base of the thyroid gland and divides into superior (ascending) and inferior thyroid branches to supply the inferior and posterior surfaces of the gland. The superior branch also supplies the parathyroid glands. The relationship between the inferior thyroid artery and the recurrent laryngeal nerve is highly variable and of considerable clinical importance: iatrogenic injury to the nerves that supply the larynx represents a major complication of thyroid surgery (Yalcxin 2006). The recurrent laryngeal nerve is usually related to the posterior branch of the inferior thyroid artery, which may be replaced by a vascular network (Moreau et al 1998).

Veins