Nausea and Vomiting

Perspective

Pathophysiology

The act of vomiting can be divided into three distinct phases: nausea, retching, and actual vomiting (Fig. 29-1). Nausea may occur without retching or vomiting, and retching may occur without vomiting. Nausea is defined as a vague and extremely unpleasant feeling that often precedes vomiting. The exact neural pathways mediating nausea are not clear, but they are likely to be the same pathways that mediate vomiting. Mild activation of the pathways may result in nausea, whereas more intense stimulation results in vomiting. During nausea there is an increase in tone in the musculature in the duodenum and jejunum, with a concomitant decrease in gastric tone; this leads to reflux of intestinal contents into the stomach. There is often associated hypersalivation, repetitive swallowing, and tachycardia.

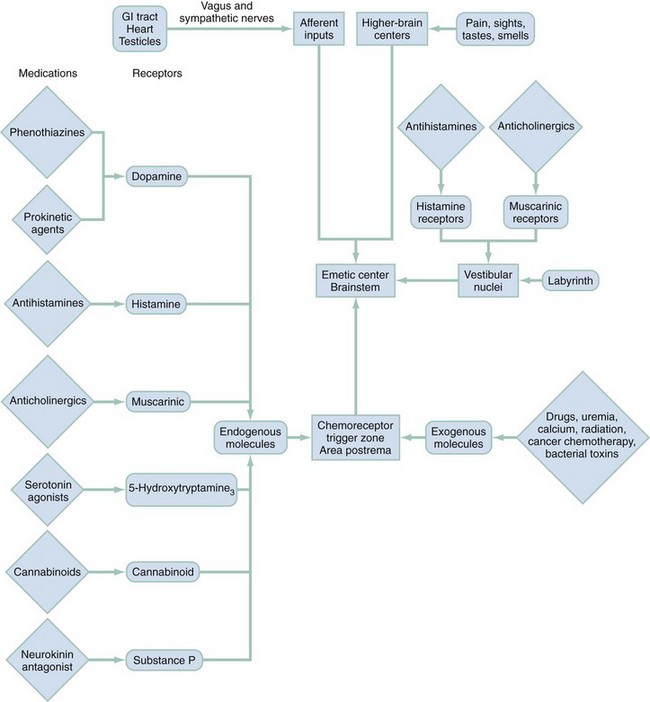

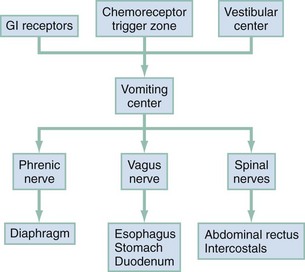

The complex act of vomiting is not completely understood but is thought to be coordinated by a vomiting center located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla (Fig. 29-2). The efferent pathways from the vomiting center are mainly through the vagus, phrenic, and spinal nerves. These pathways are responsible for the integrated response of the diaphragm, intercostal muscles, abdominal muscles, stomach, and esophagus. The vomiting center is activated by afferent stimuli from a variety of sources. These include vagal and sympathetic impulses directly from the GI tract. Direct irritation of the stomach lining causes vomiting in this way. Other GI sources of afferent impulses include the pharynx, small bowel, colon, biliary system, and peritoneum. Receptors also are found outside the GI tract in the vestibular system, heart, and genitalia.

Figure 29-2 Vomiting process. GI, gastrointestinal.

Diagnostic Approach

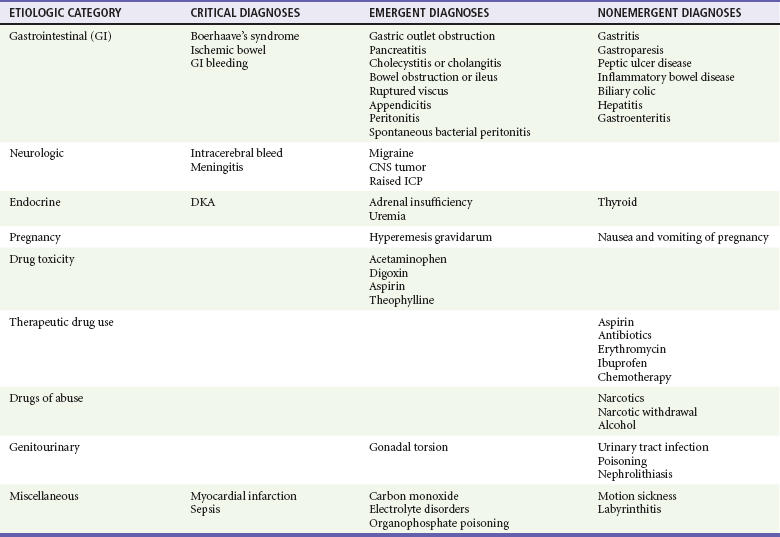

The differential diagnosis for nausea and vomiting is particularly broad in scope; almost any organ system can be involved (Table 29-1). Vomiting also can result in complications, which must be considered in addition to the causes. The sequelae of vomiting may include the following:

Table 29-1

Differential Diagnosis of Nausea and Vomiting

CNS, central nervous system; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; ICP, intracranial pressure.

Hypovolemia is caused by loss of water and sodium chloride in the vomitus. The contraction of the extracellular fluid space leads to activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Metabolic alkalosis is produced by loss of hydrogen ions in the vomitus. Many factors serve to maintain the alkalosis, including volume contractions, hypokalemia, chloride depletion, shift of extracellular hydrogen ions into cells, and increased aldosterone.

Hypokalemia is produced primarily by loss of potassium in the urine. The metabolic alkalosis leads to large amounts of sodium bicarbonate being delivered to the distal tubule. Secondary hyperaldosteronism from volume depletion causes reabsorption of sodium and excretion of large amounts of potassium in the urine.

Mallory-Weiss tears typically result from a forceful bout of retching and vomiting. The lesion itself is a 1- to 4-cm tear through the mucosa and submucosa; 75% of cases occur in the stomach, with the remainder near the gastroesophageal junction. Bleeding usually is mild and self-limited; however, 3% of deaths from upper GI bleeds are a result of Mallory-Weiss tears.

Boerhaave’s syndrome refers to a perforation of all layers of the esophagus occurring as a result of forceful retching or vomiting. The overlying pleura is torn so that there is free passage of esophageal contents into the mediastinum and thorax; 80% of cases involve the posterolateral aspect of the distal esophagus. Boerhaave’s syndrome constitutes a surgical emergency. The mortality rate has been reported as 50% if surgical repair is not performed within 24 hours.

Aspiration of gastric contents is a concern in patients who have altered mental status or pulmonary findings after an episode of vomiting. Patients with pulmonary findings after vomiting need further evaluation for aspiration.

Rapid Assessment and Stabilization

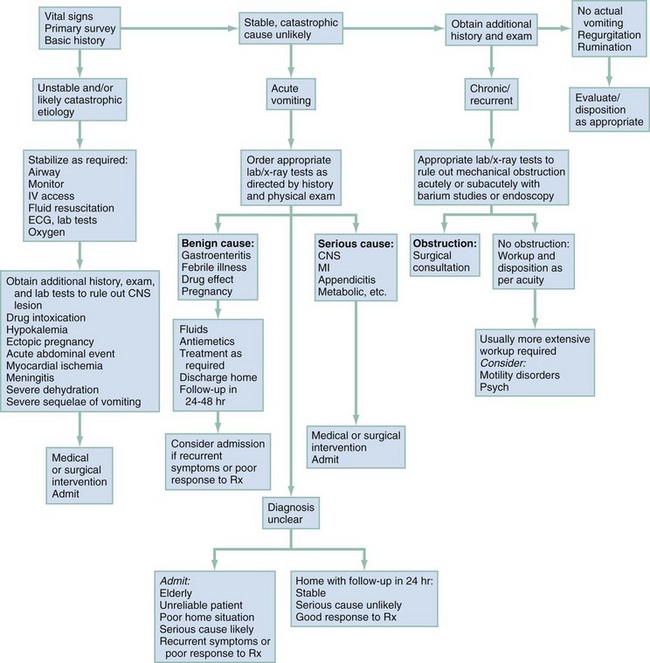

The initial assessment is directed toward the patient’s hemodynamic status and identification of the critical causes or sequelae of vomiting (see Table 29-1). Data gathered include duration of vomiting, whether blood is in the vomitus, symptoms of volume depletion, and associated symptoms pointing to serious underlying disease. Physical findings include level of consciousness, abdominal examination, rapid neurologic screen, and serial vital signs. Initial stabilization may include establishing intravenous access and fluid resuscitation in patients with signs of volume depletion, cardiac monitoring, and therapeutic measures directed toward specific underlying diseases (e.g., nasogastric tube for intractable vomiting in the setting of a small bowel obstruction) (Fig. 29-3).

Pivotal Findings

Physical Examination

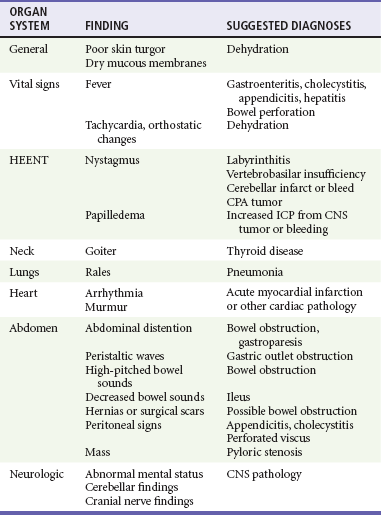

The important physical examination findings are outlined in Table 29-2. During evaluation, findings of jaundice, lymphadenopathy, nystagmus, fever, and goiter can help determine the cause of the disease. Oral examination may reveal loss of dental enamel commonly seen with bulimia. Abdominal examination may reveal ascites, distention, hernias, abdominal tenderness and masses, organomegaly, or hyperactive or hypoactive bowel sounds, with appropriate laboratory testing for occult blood in the stool. Orthostatic vital signs often are obtained but are of limited value in determination of the extent of dehydration, and results should not alter clinical decision-making. It also is important to evaluate neurologic status (including cranial nerve evaluation, funduscopic examination, and gait observation) to rule out a central cause of a patient’s symptoms. Provocative testing for vertigo such as with the Nylen-Barany test may elicit nausea and vomiting. Attentive physicians may elicit evidence of depression or anxiety that may lead to a psychiatric diagnosis.

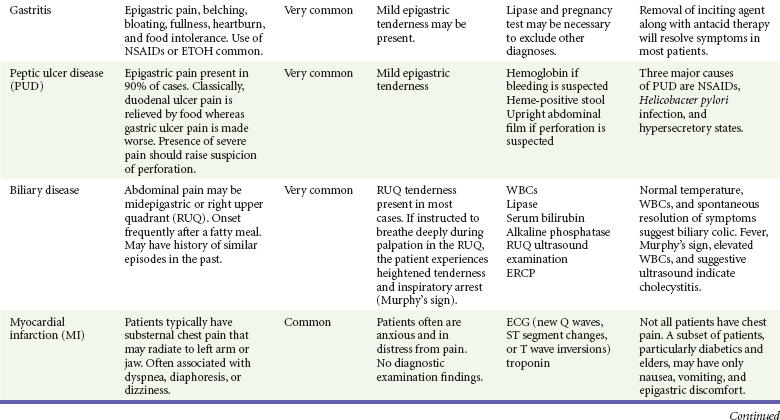

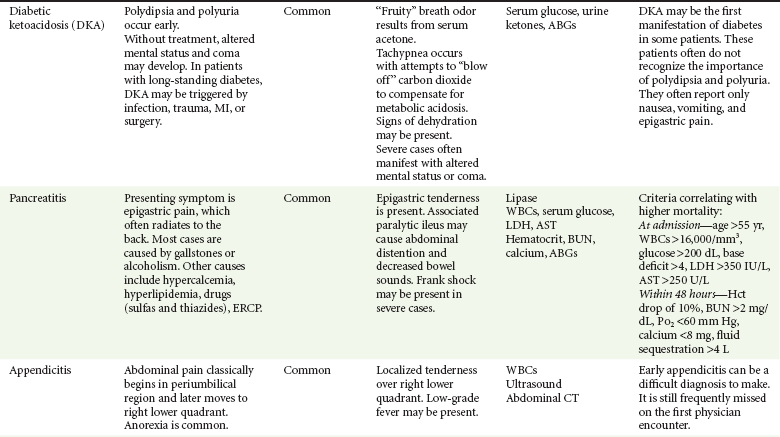

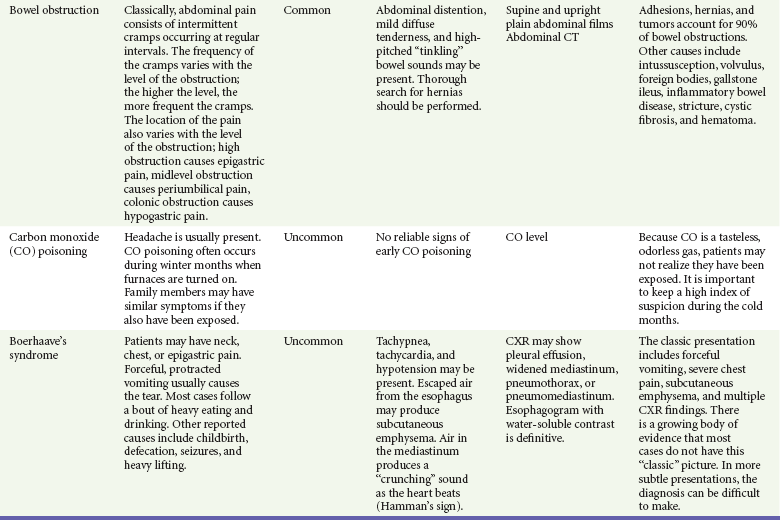

Differential Diagnosis

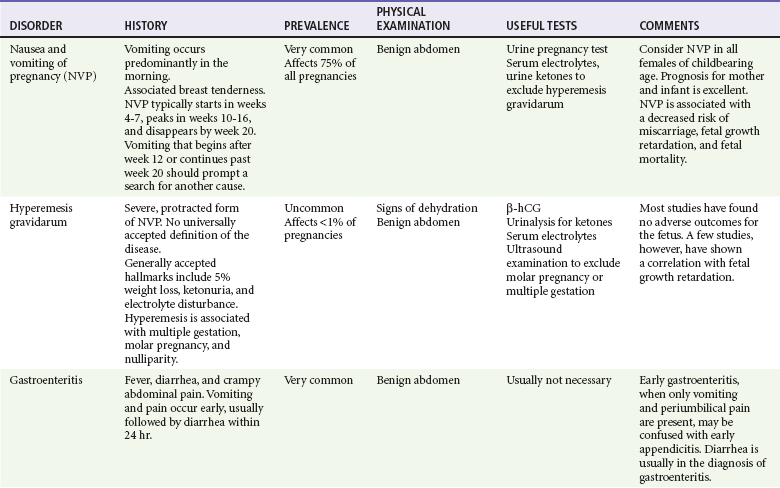

Clinical and diagnostic findings are helpful in differentiating among the common and catastrophic causes of nausea and vomiting (Table 29-3). The differential diagnosis in adults is extensive; etiologic categories include medication-induced causes, infectious and toxic causes, disorders of the GI tract, CNS causes, pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting, endocrine and metabolic disorders, radiation-induced nausea and vomiting, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), unknown (as in cyclic vomiting), psychogenic causes, and other causes such as acute myocardial infarction and acute graft-versus-host disease.

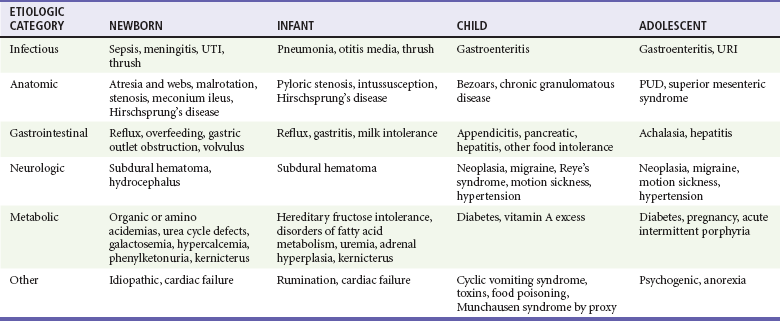

Pediatric Considerations

The evaluation and management of pediatric patients with nausea and vomiting depend on age and likely causative disorders (Table 29-4). Mild degrees of reflux and associated regurgitation are common in the first few months of life, but vomiting in infancy can be associated with life-threatening illness. In the first week of life, obstructive lesions of the alimentary tract, inborn errors of metabolism, and serious infectious processes are associated with vomiting. After the first week of life, pyloric stenosis needs to be considered. The diagnosis of “feeding problems” should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. After the first month of life, infections, metabolic diseases, cow’s milk intolerance, failure to thrive, and subdural hematoma from abuse should be prime considerations. Thereafter, various disorders are associated with vomiting, including recurrent cyclic vomiting, acute surgical emergencies, food poisoning, toxic ingestion, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, pneumonia, and diabetic ketoacidosis. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia should be considered in teenagers with recurrent vomiting.

Table 29-4

Etiology of Nausea and Vomiting in Pediatric Age Groups

PUD, peptic ulcer disease; URI, upper respiratory infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Adapted from Li HK, Sunku BK: Vomiting and nausea. In Wyllie R, Hyams JS, eds: Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:127-149.

Management

Symptomatic relief of nausea and vomiting should not await identification of the underlying cause. Decreased oral intake is a major cause of dehydration and malnutrition. If the patient is able to take oral liquids, a solution containing sodium, carbohydrate, and water is recommended. Many sports drinks contain the proper balance of these elements.1 Patients who are dehydrated and in whom intake of oral fluids is not possible or is contraindicated should be given intravenous fluids. Hypokalemia is rarely of clinical significance but may be found with profound vomiting secondary to contraction metabolic alkalosis. Treatment of the underlying condition with administration of intravenous fluids is indicated. Placement of a nasogastric tube is an option in some cases of refractory vomiting in patients with gastroparesis, pancreatitis, or bowel obstruction.

Pharmacologic management of patients with nausea and vomiting is outlined in Table 29-5. To allow the physician to make an appropriate choice for each patient, the pharmacologic therapies available may be classified into histamine antagonists, muscarinic antagonists, dopamine antagonists, and serotonin antagonists.

Table 29-5

Commonly Used Medications for the Treatment of Nausea and Vomiting

| MEDICATION | DOSE | COMMENTS |

| Promethazine (Phenergan) | Adult: 12.5-25 mg IV, IM, PO, or by rectum Pediatric: 0.25-1 mg/kg/dose q4-6h prn IV, IM, PO, or by rectum; max 25 mg/dose |

May be repeated every 4-6 hr until cessation of vomiting. May cause dry mouth, dizziness, blurred vision. Boxed warning for use under 2 yr old. |

| Prochlorperazine (Compazine) | Adult: 5-10 mg IM or PO; 2.5-10 mg IV; 25 mg by rectum Pediatric: 0.4 mg/kg/24 hr tid-qid PO or by rectum; 0.1-0.15 mg/kg/dose tid-qid IM; max 40 mg/24 hr |

May be repeated every 4 hr IV or IM or every 12 hr by rectum until cessation of vomiting. May cause lethargy, hypotension, extrapyramidal effects. |

| Metoclopramide (Reglan) | Adult: 10 mg IM or IV, may repeat q6h Pediatric: 1-2 mg/kg/dose q2-6h IV q2-3h |

May cause dystonic reactions, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome. |

| Ondansetron (Zofran) | Adult: 4 mg IV single dose Pediatric: up to 40 kg: 0.1 mg/kg; >40 kg: 4 mg/dose IV single dose |

May cause headache, dizziness, and musculoskeletal pain. |

IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; prn, as needed.

The prokinetic agents are useful in patients with gastroparesis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and other putative dysmotility syndromes. Metoclopramide (Reglan) has the most applicability in the ED. It has dopamine antagonist activity at the CTZ and exerts anticholinergic and antiserotonin effects. The primary effect is increased gastric emptying; the exact mechanism for this is not understood. Metoclopramide has multiple antiemetic actions and may be used as a general-purpose agent. Metoclopramide has been associated with tardive dyskinesia, prompting the Food and Drug Administration to issue a black box warning.2 The most common side effects of metoclopramide are restlessness, drowsiness, and diarrhea. These effects are usually mild and transient.

Benzodiazepine medications have been used for nausea and vomiting with variable results. Limited studies have evaluated the efficacy of benzodiazepines in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum, in prophylaxis for emetogenic chemotherapy, and preoperatively for minor gynecologic surgery. Although this aspect was not directly measured in these studies, the researchers inferred that part of the response may be related to the anxiolytic component.3–5 No studies have addressed the use of benzodiazepines to treat nonspecific nausea and vomiting in an ED population.

An oral neurokinin-1 antagonist, aprepitant (Emend), has been found to be an effective adjunctive agent for use in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy.6 Aprepitant blocks the effects of substance P in the brain. Currently, it is not indicated for use in patients with established nausea and vomiting.

Adjuncts to pharmacologic agents have been investigated with limited results. Increased inhaled oxygen as well as ginger and ginger extract have not been found to be effective. Investigations of intravenous fluids have not been definitive in the treatment of nausea and vomiting. The use of acupressure point P6 on the wrist has been found to be effective as compared with placebo.7

The medication choice is directed at the underlying cause of the nausea and vomiting, if known, such as motion sickness, PONV, or nausea and vomiting related to cancer chemotherapy. For all other patients, the choice of antiemetic agent has not been well studied in emergency medicine. One study found droperidol to be more effective than prochlorperazine or metoclopramide as compared with placebo for moderate to severe nausea of any cause.8 There also has been limited research regarding the preferred agents for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in the field. One study found that ondansetron was moderately effective in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in this setting.9 The need for antiemetics and the response to therapy may be measured with scales similar to those used for pain assessment, such as the visual analog scale and the verbal categorical scale.10

As with adults, the underlying cause of nausea and vomiting in children is first addressed in determining treatment choices. Most agents used in adults are recommended for children in a weight-based dosing regimen. Ondansetron and metoclopramide have value for antiemetic treatment to reduce nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients. These agents are particularly effective in improving the ability of patients with gastroenteritis to maintain oral hydration.11

Special Situations

Medications such as antihistamines are frequently used in the mistaken belief that they reduce the incidence of nausea and vomiting when opioid analgesics are administered in the ED for pain control. Studies have demonstrated that the incidence of nausea and vomiting related to opioid administration in the ED is low and that these medications have little efficacy in reducing nausea and vomiting.12,13

Many agents have been advocated for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP). The treatments include nonpharmacologic methods—avoiding triggers, making dietary changes, using acupuncture or acupressure, taking ginger, and undergoing behavioral therapy—and pharmacologic therapies—pyridoxine, antihistamines, metoclopramide, ondansetron, or prochlorperazine. Hyperemesis gravidarum is treated essentially the same as NVP. For mild symptoms, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), acupressure, ginger, and administration of antiemetics including antihistamines, metoclopramide, ondansetron, prochlorperazine, and phenothiazines may be used. Pyridoxine, acupressure, and ginger are thought to be of benefit but are not commonly used in the ED. For severe symptoms, hospitalization, fluids, corticosteroids, and electrolyte replacement may be needed. No specific medication has been shown to be superior to others in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum.11

Chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting may be seen in ED patients. The chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting may be acute (up to 24 hours) or delayed (after 24 hours).13 The incidence of nausea and vomiting is correlated with the emetic potential of the chemotherapeutic agents, the patient’s risk factors and other comorbid disorders, and antiemetic treatment. Patients commonly are given the serotonin antagonists dexamethasone and aprepitant for both immediate and delayed prophylaxis. Cannabinoids also have been used to control chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Choice of agents for the ED treatment of chemotherapy-induced vomiting has not been studied, but the serotonin antagonists and aprepitant are often used.

Disposition

Close follow-up often is advisable for discharged patients, preferably with their primary care physician, in 24 to 48 hours. At discharge, the patient is prescribed medications as needed and is advised to restart oral intake with small feedings of a liquid diet with gradual return to a normal diet. Some experts have recommended the nausea and vomiting diet, which requires the least amount of gastric neuromuscular work. It is a three-step diet: Sports drinks and bouillon are recommended in step 1; soups are recommended in step 2; and foods that require the least amount of gastric “work” are recommended in step 3, such as meals high in protein and low in lipids.13 Evidence supporting this recommendation, though, is scant. Clear instructions are given to return to the ED if there is a recurrence, change, or deterioration in symptoms.

References

1. Hartling, L, et al. Oral versus intravenous rehydration for treating dehydration due to gastroenteritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2006.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Metoclopramide-containing drugs. www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumaNMedicalProducts/ucm106942.htm.

3. Tasci, Y, Demir, B, Dilbaz, S, Haberal, A. Use of diazepam for hyperemesis gravidarum. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:353–356.

4. Perwitasari, DA, et al. Anti-emetic drugs in oncology: pharmacology and individualization by pharmacogenetics. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:33–43.

5. Fujii, Y, Itakura, M. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study to assess the antiemetic effects of midazolam on postoperative nausea and vomiting in women undergoing laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1633–1637.

6. Braude, D, et al. Antiemetics in the ED: A randomized controlled trial comparing 3 common agents. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:177.

7. Meek, R, Epi, MC, Kelly, AM, Hu, XF. Use of the visual analog scale to rate and monitor severity of nausea and monitor severity of nausea in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1304–1310.

8. Stork, CM, Brown, KM, Reilly, TH, Secreti, L, Brown, LH. Emergency department treatment of viral gastritis using intravenous ondansetron or dexamethasone in children. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1027.

9. Paoloni, R, Talbot-Stern, J. Low incidence of nausea and vomiting with intravenous opiate analgesia in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:604.

10. Bradshaw, M, Sen, A. Use of a prophylactic antiemetic with morphine in acute pain: Randomized controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:210.

11. Jewell, D, Young, G. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2003.

12. Carlisle, JB, Stevenson, CA. Drugs for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2006.

13. Herrstedt, J, Dombernowsky, P. Anti-emetic therapy in cancer chemotherapy: Current status. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;101:143.