CHAPTER 14 Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea, retching, and vomiting may occur separately or together. When they occur together they are often in sequence, as manifestations of the various physiologic events that integrate the emetic reflex. Vomiting is a complex act that requires central neurologic coordination, whereas nausea and retching do not imply activation of the vomiting reflex. When nausea, retching, or vomiting manifest as isolated symptoms, their clinical significance may differ from the stereotypical picture of emesis.1,2

Vomiting is a partially voluntary act of forcefully expelling gastric or intestinal content through the mouth. Vomiting must be differentiated from regurgitation, an effortless reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus that sometimes reaches the mouth but is not usually associated with the forceful ejection typical of vomiting (see Chapter 12).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

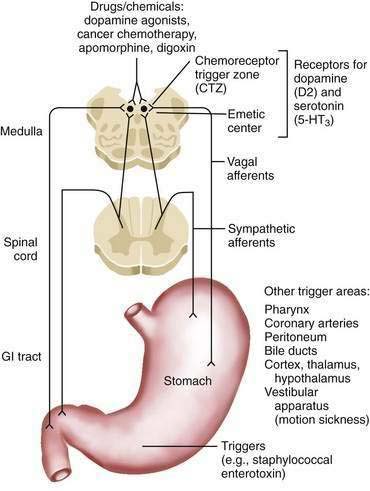

The mechanism of vomiting has been well characterized in experimental animals and humans (Fig. 14-1).3 Neurologic coordination of the various components of vomiting is provided by the emetic center (or vomiting center) located in the medulla, specifically in the dorsal portion of the lateral reticular formation in the vicinity of the fasciculus solitarius. The afferent neural pathways that carry activating signals to the emetic center arise from many locations in the body. Afferent neural pathways arise from various sites along the digestive tract—the pharynx, stomach, and small intestine. Afferent impulses from these organs are relayed at the solitary nucleus (nucleus tractus solitarius) to the emetic center. Afferent pathways also arise from nondigestive organs such as the heart and testicles. Pathways from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) located in the area postrema on the floor of the fourth ventricle activate the emetic center. Despite its central location, the CTZ is outside, at least in part, the blood-brain barrier and serves primarily as a sensitive detection apparatus for circulating endogenous and exogenous molecules that may activate emesis. Finally, pathways arise from other central nervous system structures, including the cortex, brainstem, and vestibular system, via the cerebellum.

Figure 14-1. Schematic of the proposed neural pathways that mediate vomiting. GI, gastrointestinal; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

The circuitry of the emetic reflex involves multiple receptors.4 The following elements are the most relevant to clinical issues:

When activated, the emetic center sets into motion, through neural efferents, the various components of the emetic sequence.11 First, nausea develops as a result of activation of the cerebral cortex; the stomach relaxes concomitantly, and antral and intestinal peristalsis are inhibited. Second, retching occurs as a result of activation of spasmodic contractions of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles combined with closure of the glottis. Third, the act of vomiting occurs when somatic and visceral components are activated simultaneously. The components include brisk contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, and a forceful retrograde peristaltic contraction in the jejunum that pushes enteric content into the stomach and from there toward the mouth.12 Simultaneously, protective reflexes are activated. The soft palate is raised to prevent gastric content from entering the nasopharynx, respiration is inhibited momentarily, and the glottis is closed to prevent pulmonary aspiration, which is a potentially serious complication of vomiting. Other reflex phenomena that may accompany this picture include hypersalivation, cardiac arrhythmias, and passage of gas and stool rectally.

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF VOMITING

Certain clinical features may be characteristic of specific causes of vomiting. Nausea and vomiting that occur in the morning or with an empty stomach and with emission of mucoid material (swallowed saliva) or gastroenteric secretions are characteristic of vomiting produced by direct activation of the emetic center or CTZ. This type of emesis is most typical of pregnancy, drugs, toxins (e.g., alcohol abuse), or metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus, uremia). Psychogenic vomiting also may exhibit these characteristics. Clinical tradition holds that excessive nocturnal postnasal drip may be responsible for this type of vomiting, although direct evidence for this association is lacking. Vomiting that occurs outside the immediate postprandial period and that is characterized by evacuation of retained and partially digested food is typical of slowly developing gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis.13 Pseudovomitus, in which totally undigested food that has not been exposed to gastric juice is expelled, may occur in long-standing achalasia or with a large Zenker’s diverticulum. Bilious vomiting is commonly seen after multiple vomiting episodes occur in close succession because of retrograde entry of intestinal material into the stomach. It is also characteristic of patients with a surgical enterogastric anastomosis, in whom the gastric contents normally include bile-stained enteric refluxate. Vomitus with a feculent odor suggests intestinal obstruction, ileus associated with peritonitis, or long-standing gastric outlet obstruction. Vomiting that develops abruptly without preceding nausea or retching (projectile vomiting) is characteristic of, but not specific for, direct stimulation of the emetic center, as may occur with intracerebral lesions (tumor, abscess) or increased intracranial pressure.14

CAUSES

In clinical practice, establishing the cause of vomiting promptly is critical, because specific treatment may be feasible. Acute (less than 1 week) and chronic vomiting should be considered separately, because the respective causes generally differ. Patients with chronic vomiting tend to consult a specialist after being symptomatic for some time, whereas patients with severe acute vomiting require immediate medical attention. Causes of nausea and vomiting are listed in Table 14-1.

ACUTE VOMITING

In the patient with acute vomiting, the following two questions must be answered immediately:

Acute Intestinal Obstruction

Vomiting may be a presenting feature of intestinal obstruction caused by an incarcerated hernia or stool impaction; the latter entity is seen in older, debilitated, or mentally retarded persons. Distal duodenal and proximal jejunal neoplasms (adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma, carcinoid) may cause gastric outlet or intestinal obstruction that manifests as acute or chronic vomiting. Proximal intestinal obstruction may be particularly difficult to diagnose because the obstructing lesion may be overlooked or unreachable by conventional upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and yet may present without the typical picture of dilated fluid-filled loops of small bowel (air-fluid levels) on plain abdominal films (see Chapter 119).

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

In the past, peptic ulcer disease was a major cause of gastric outlet obstruction (see Chapter 52). Before the 1980s, 12% of patients with a peptic ulcer presented with gastric outlet obstruction, either as a direct consequence of a pyloric channel ulcer with associated edema and pylorospasm or, more commonly, as a result of marked deformity of the entire antroduodenal region in the setting of long-standing ulcer disease. Obstruction caused by a peptic ulcer can occur abruptly with acute vomiting or insidiously, mimicking the clinical picture of gastroparesis (see Chapter 48). As the incidence of peptic ulcer disease has declined sharply and patients are treated early and more effectively in the course of the disease, peptic ulcer disease has become a much less frequent cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Gastric volvulus is a relatively uncommon but important cause of acute vomiting; symptoms may be relapsing as a result of intermittent volvulus formation and spontaneous resolution. Paraesophageal and post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias also may predispose to acute vomiting as a result of obstruction (see Chapter 24).15

Both acute and chronic pancreatitis, with associated inflammatory masses, necrosis, pseudocysts, or secondary infection, may lead to gastric outlet obstruction at the duodenum or, less commonly, the antrum and pylorus (see Chapters 58 and 59). Similarly, gastric, duodenal, or pancreatic malignancies (adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, cystic pancreatic neoplasms) may cause gastric outlet obstruction, sometimes manifesting as acute vomiting (see Chapters 29–32, 54, 60, and 121).

Intestinal Infarction

A diagnosis of intestinal infarction should be considered in any patient with acute vomiting.16 Intestinal infarction may occur with a paucity of physical signs but requires expeditious management. The diagnosis is more common in patients with vascular disorders and thrombotic diatheses and in older adults (see Chapter 114).

Extraintestinal Causes

Extraintestinal causes of vomiting usually do not present a challenging diagnostic problem because the primary condition is generally clinically apparent. Myocardial infarction may manifest initially as acute vomiting because of afferent connections between the heart and the emetic center. Renal colic and biliary pain similarly may manifest with intense vomiting, although the localization of the pain and other characteristic features usually make these diagnoses evident (see Chapter 65). Ovarian or testicular torsion may manifest initially with intense vomiting.

Intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal inflammatory conditions, including acute appendicitis, bowel perforation, acute pancreatitis and, in general, any cause of acute abdominal pain, may be associated with vomiting. On occasion, vomiting may be so intense (and, rarely, the only symptom) as to cause diagnostic confusion (see Chapters 10, 26, 37, and 116).

Toxins and Drugs

Cancer chemotherapy is associated with a high likelihood of nausea and vomiting, although routine administration of antiemetic agents before chemotherapy often prevents nausea and vomiting. Vomiting also can be induced by radiotherapy. Chemotherapeutic agents and combinations of agents vary in their propensity to cause nausea and vomiting (see Table 14-1).17,18

The list of drugs that can induce nausea and vomiting is lengthy (see Table 14-1). Some classes of drugs and individual agents are particularly common culprits in clinical practice, especially aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; their emetic effect is attenuated partially by coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor; see Chapter 52), cardiovascular drugs (digitalis, antiarrhythmics), antibiotics, levodopa and its derivatives, theophylline, opiates, and azathioprine. Patients on multidrug regimens pose a special challenge in determining which drug (or drugs) is the culprit.

Metabolic Causes

Metabolic causes of vomiting include diabetic ketoacidosis, hyponatremia, and hypercalcemia. Diabetic gastroparesis associated with visceral neuropathy is usually associated with chronic relapsing nausea and vomiting (see later). The clinical onset of diabetic gastroparesis, however, may be abrupt (see Chapter 48). Addison’s disease also may manifest clinically with acute vomiting.

Infectious Causes

Vomiting may be caused by acute gastritis or gastroenteritis caused by a virus or bacterium, including bacterial toxins, such as that produced by Staphylococcus.19 During the early stages of the illness, nausea and vomiting may be the predominant or even exclusive clinical manifestation (see Chapters 51 and 107).

Neurologic Causes

Nausea and vomiting may be the sole or predominant manifestation of neurologic disorders. Meningeal inflammation is another potential cause. Nausea and vomiting may be associated with vertigo in patients with vestibular or cerebellar disorders and motion sickness. Migraine headaches may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting with little or no headache, making the diagnosis difficult. Ictal vomiting is a rare manifestation, most often associated with right temporal lobe epilepsy.20 Intracerebral lesions associated with increased intracranial pressure, interference with intracerebral fluid flow, or direct compression of the emetic center may manifest with nausea and vomiting. Projectile vomiting is a common but not invariable feature of intracerebral lesions.

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Postoperative nausea and vomiting is generally a therapeutic rather than a diagnostic problem. About one third of patients who do not receive antiemetic prophylaxis will experience nausea and vomiting after surgery.21 The risk is highest with abdominal, gynecologic, strabismus, and middle ear surgery, and is three times as common in women as in men. The differential diagnosis includes complications of surgery, such as intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and electrolyte disturbances. Cardiac disease (“silent” myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure) also may manifest as nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period.

CHRONIC OR RELAPSING VOMITING

Partial Intestinal Obstruction

In contrast to acute complete intestinal obstruction, partial intestinal obstruction may be associated with relapsing vomiting over long periods of time. Abdominal pain and distention may accompany the clinical picture but may wax and wane as intestinal flow is intermittently interrupted and spontaneously restored. The clinical presentation of long-standing partial intestinal obstruction and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (an intestinal motor disorder) may be similar. In fact, exclusion of occult partial intestinal obstruction is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of pseudo-obstruction (see Chapters 119 and 120). Stenotic Crohn’s disease, neoplasms of the intestine, and ischemic strictures are the main causes of partial mechanical intestinal obstruction (see Chapters 111, 114, and 121). Chronic adhesions from surgery or pelvic inflammatory disease are also potential causes of intestinal obstruction, although establishing their pathogenic role is sometimes difficult. Advanced intra-abdominal cancer is another important cause of intestinal obstruction.22 In older, debilitated, and mentally retarded individuals, constipation may lead to a picture of intestinal obstruction when the colon becomes impacted with stool and ileal outflow is partially impeded (see Chapter 18).23

Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders

Gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction may produce chronic vomiting.13,24 Recurrent vomiting, sometimes with symptom-free periods, is a major component of the clinical picture of gastroparesis. As in partial gastric outlet obstruction, abdominal pain is absent, the stomach may become markedly dilated, and the vomitus may contain partially digested food, but these findings are not constant. Some patients with neuropathic gastroparesis, as is associated with diabetes mellitus, may vomit repeatedly, even with an empty stomach; epigastric pain may occur. Nausea and vomiting may be presenting features of intestinal pseudo-obstruction, but other symptoms and signs associated with small bowel dysmotility, such as abdominal pain and distention, are usually present. The distinction between primary and secondary forms of gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction often requires specific diagnostic tests (see later; see also Chapters 48 and 120).

NAUSEA AND VOMITING DURING PREGNANCY

Nausea occurs in more than half of all normal pregnancies and frequently is associated with vomiting.25 These symptoms tend to develop early in pregnancy, peak around 9 weeks of gestation, and rarely continue beyond 22 weeks of gestation. Nausea with vomiting is more common in women with multiple gestations than with a single gestation. The origin of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy remains unclear, although hormonal and psychological influences appear to contribute.26,27 Gastric dysrhythmias have been documented by electrogastrography (see Chapter 48). The symptoms may occur even before a woman realizes that she is pregnant; therefore, a pregnancy test must be obtained in any fertile woman with a complaint of nausea and vomiting.28

Nausea and vomiting tend to occur primarily, although not exclusively, in the morning, before food is ingested. The symptoms may warrant pharmacotherapy to alleviate the discomfort they produce but must be regarded as a normal manifestation of pregnancy.29 The prognosis for mother and child is excellent. Drugs that may be used safely to treat nausea and vomiting during pregnancy, as based on published data, include vitamin B6, ondansetron and related 5-HT3 antagonists,30 metoclopramide, and doxylamine, an antihistamine with antiemetic properties available in some European countries.31 Other antiemetics also may be safe, but specific evidence in support of their use is not available. Ancillary nonpharmacologic measures may be helpful.32,33

Hyperemesis gravidarum refers to unusually severe nausea and vomiting that leads to complications (e.g., dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, malnutrition). Multiparous overweight women are at increased risk.34 The syndrome appears to represent an exaggeration of the common nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, and hormonal and psychological factors also are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis. Hyperthyroidism has been reported in some affected persons. The manifestations generally develop in, and may continue beyond, the first trimester. Fluid and electrolyte replacement therapy may be required, together with antiemetic drugs. Glucocorticoids, erythromycin, and powdered ginger root have been reported to be helpful in patients with hyperemesis gravidarum. Behavioral modification and other psychotherapeutic techniques have been reported to be helpful as well. Occasionally, enteral or parenteral nutrition may need to be prescribed to prevent severe malnutrition.35 Patients with hyperemesis gravidarum, however, do not have an increased risk of toxemia of pregnancy or spontaneous abortion, and the condition does not lead to an increased rate of adverse fetal consequences.36

Severe vomiting may accompany acute fatty liver of pregnancy, a serious but uncommon condition that occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy (in contrast to hyperemesis gravidarum).37 Headache, general malaise, and manifestations of preeclampsia (hypertension, edema, proteinuria) are common accompanying features. Progression to hepatic failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation may occur rapidly. Therefore, measurement of serum liver biochemical test levels is advisable in women in whom severe nausea and vomiting develop late in pregnancy. The detection of elevated serum aminotransferase levels may warrant a liver biopsy, which characteristically discloses microvesicular steatosis. The differential diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy includes fulminant viral hepatitis and drug-induced hepatitis. If the diagnosis of acute fatty liver is confirmed, the pregnancy should be terminated immediately to prevent maternal and fetal death (see Chapter 38).

FUNCTIONAL VOMITING

Consensus criteria for functional vomiting by the Rome III Committee on Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders include one or more episodes of vomiting per week for 3 months, with the onset of symptoms at least six months prior to diagnosis. Eating disorders, rumination, self-induced vomiting, major psychiatric disorders, chronic cannabinoid use, and organic causes of vomiting (i.e., with a definable structural or physiologic basis) should be excluded (see Chapters 8 and 21).38

CYCLIC VOMITING SYNDROME

First recognized in the 19th century, cyclic vomiting syndrome is characterized by clustered episodes of vomiting that last from one day to three weeks (average, six days). The vomiting episodes tend to be stereotypical, with a predictable onset and duration separated by asymptomatic or almost asymptomatic intervals that range from two weeks to six months; sometimes, mild to moderate dyspeptic symptoms persist between episodes of vomiting. Some patients describe a prodromal phase resembling that associated with a migraine.39 The Rome III committee’s definition of cyclic vomiting syndrome requires three or more discrete episodes of vomiting (with no apparent explanation) during the preceding year.38

A personal or family history of migraine is supportive of the diagnosis of cyclic vomiting syndrome, particularly in children. Also, in the pediatric age group, various mitochondrial, ion channel, and autonomic disorders have been associated with intermittent episodes of vomiting and may need to be excluded. Similarly, food allergy (sensitivity to cow’s milk, soy, or egg white protein) or food intolerances (to chocolate, cheese, nuts, or monosodium glutamate) may manifest with vomiting spells and should be excluded (see Chapter 9).

Cyclic vomiting syndrome may occur in adults of any age, although the disorder is uncommon in older adults. There is no gender predilection. A history of migraine headaches is elicited in only one fourth of patients, and abdominal pain may be an accompanying feature in two thirds of affected persons.40 Transient fever and diarrhea also may occur. In some women, the vomiting episodes are linked to the menstrual cycle. Although cyclic vomiting syndrome has features that suggest an episodic central nervous system disorder, such as migraine or cluster headaches, studies have suggested that a high percentage of these patients have underlying intestinal motor disturbances.41 An association between chronic cannabis abuse and cyclic vomiting has been described.42 A useful diagnostic feature is the associated urge to take hot baths or showers during the active phase of the illness. Patients who discontinue cannabis recover completely.

Diagnostic evaluation of cyclic vomiting should proceed along the lines described for chronic vomiting, with an emphasis on excluding neurologic diseases, chronic partial small bowel obstruction, and disordered gastric emptying. If gastrointestinal manometric studies are abnormal, a laparoscopic full-thickness biopsy of the small bowel should be considered to diagnose genetic and acquired myogenic or neurologic causes of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Testing for mitochondrial disorders (chiefly mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy [MNGIE]; see Chapter 35) and food allergies or intolerances (see Chapter 9) should be considered as well.

That some patients have a personal or family history of migraine headaches has stimulated the use of antimigraine drugs, especially serotonin 5-HT1 agonists (e.g., sumatriptan), given by a subcutaneous, transnasal, or oral route. Such drugs are relatively contraindicated in patients with a history of ischemic heart disease, ischemic stroke, and uncontrolled hypertension. Similarly, beta receptor blockers such as propranolol have been used as preventive therapy and reportedly have helped some patients by reducing the frequency of or abolishing vomiting spells.43 Antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or tricyclics also have been used, although evidence from clinical trials is lacking.44 Other agents that have been reported anecdotally to help include cyproheptadine, naloxone, carnitine, valproic acid, and erythromycin. Even though habitual cannabis abuse may apparently induce cyclic vomiting syndrome, other reports have emphasized the therapeutic value of marijuana smoking in patients with the syndrome.40

SUPERIOR MESENTERIC ARTERY SYNDROME

Although some objective basis exists for the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome, the diagnosis tends to be applied inappropriately to patients with functional vomiting or cyclic vomiting syndrome, who then unfortunately are subjected to unnecessary surgery.45,46 The SMA branches off the aorta at an acute angle, travels in the root of the mesentery, and crosses over the duodenum. usually just to the right of the midline. In some persons, possibly because the angle between the aorta and the SMA is or becomes more acute than normal, the duodenum is partially obstructed and the patient becomes symptomatic, usually when precipitating factors accentuate the vascular compression of the duodenum. Such precipitating factors include increased lordosis (as may occur with use of a body cast), loss of abdominal muscle tone, rapid weight loss, and abdominal surgery followed by prolonged bed rest. A somewhat analogous situation has been described in conjunction with ulcer disease, pancreatitis, or other intra-abdominal inflammatory conditions that may compress the mesenteric vessels.

The diagnosis is supported by imaging tests (upper gastrointestinal barium contrast study or computed tomography [CT] scan), which show dilatation and stasis proximal to the duodenum where the SMA crosses (Fig. 14-2). The appearance may be misleading, however, because duodenal dilatation may be caused by atony rather than mechanical obstruction.46 As noted, the SMA syndrome is often overdiagnosed. Before surgical correction is considered, stasis proximal to the site of duodenal obstruction should be demonstrated on contrast studies and, in some cases, scintigraphic tests. In specialized centers, intestinal manometry may be performed and demonstrates characteristic patterns that distinguish mechanical obstruction from a motility disorder. Finally, a feeding catheter should be passed across the obstruction into the proximal jejunum (with endoscopic assistance, if required) to demonstrate that vomiting does not occur when the obstruction is bypassed and, if necessary, to replete the patient’s nutritional status.

RUMINATION SYNDROME

Rumination resembles vomiting but does not involve an integrated somatovisceral response coordinated by the emetic center. Rather, it consists of the repetitive effortless regurgitation of small amounts of recently ingested food into the mouth followed by rechewing and reswallowing or expulsion.47,48 Characteristically, nausea and autonomic manifestations (e.g., hypersalivation, cutaneous vasoconstriction, sweating) that usually accompany vomiting are absent. In many ruminators, the process begins while the person is eating or immediately following completion of a meal. In some ruminators, rumination ceases when the regurgitated material becomes noticeably acidic. Others continue to ruminate for hours, however. In infants, in whom rumination was first described, rumination is relatively common, and typically develops between three and six months of age. The rumination process occurs without apparent distress to the ruminator and ceases when the baby is distracted by other events or sleeps, but undernutrition and dehydration, which can lead to serious complications, may occur. In adults, rumination occurs in men and women with equal frequency and at any age. According to the Rome III committee,38 rumination constitutes a distinct and unique category of functional gastroduodenal disorders.

Rumination may be diagnosed in most patients by its typical clinical features. In equivocal cases, however, the diagnosis may be confirmed by combined upper gastrointestinal manometry and 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH testing. The study may show rapid oscillations in esophageal pH induced by the repeated regurgitation and reswallowing of gastric contents. These oscillations typically cluster in the first one or two hours after ingestion of a meal. More definitive evidence of rumination is provided by the concurrence of declines in esophageal pH and sharp phasic pressure spikes recorded in the antrum and duodenum on manometry.48 The spikes correspond to abrupt increments in intra-abdominal pressure as the patient forces subdiaphragmatic intragastric content toward the esophagus through a relaxed lower esophageal sphincter. The frequency of positive manometric findings in ruminators, however, may not be high. In one study, only one third of patients showed an abnormal manometric study, with characteristic features.49

An association between rumination and anorexia nervosa or bulimia has been reported. In one study, 20% of patients with bulimia were found to ruminate, although they tended to expel rather than reswallow the regurgitated portion of the meal. In patients with bulimia, rumination may be a learned behavior used for controlling weight without resorting to (or in addition to) frank vomiting (see Chapter 8).

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

ACUTE VOMITING

There are a number of diagnostic tests that can be used.

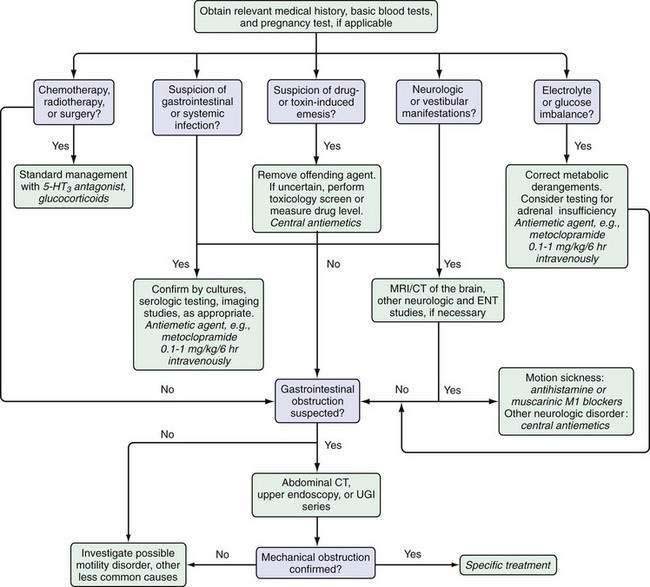

Basic Tests

As noted earlier, the evaluation of a patient with acute vomiting should begin with a carefully obtained history and a physical examination that focuses on the patient’s volume status. An algorithm for the management of the patient with acute vomiting is shown in Figure 14-3. A urine pregnancy (human chorionic gonadotropin) test should be performed in all women of childbearing potential with acute vomiting. Routine blood studies should include a complete blood count, tests of kidney function, thyroid function tests, liver biochemical tests, electrolyte, glucose, and serum amylase and lipase levels and, in some cases, arterial blood gases to assess the patient’s acid-base status.

Imaging Tests

Plain abdominal radiographs, lying and standing, should be obtained. If the films suggest small bowel obstruction, further testing to ascertain the cause of obstruction (including abdominal exploration) should be undertaken (see Chapter 119).

CHRONIC VOMITING

As noted, a detailed clinical history and careful physical examination (primarily to exclude other diagnoses) are central to the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia, functional vomiting, cyclic vomiting syndrome, and rumination syndrome. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or an upper gastrointestinal barium study, and often both, are the tests of choice for partial gastric outlet obstruction and partial duodenal obstruction. CT of the abdomen is also useful for establishing the presence of partial intestinal obstruction secondary to an intrinsic intestinal lesion or an intra-abdominal disease that can cause intestinal obstruction. CT provides information on the degree of bowel dilatation, thickness of the bowel wall, and point of transition of the caliber of the intestinal lumen. Intra-abdominal masses, as well as retroperitoneal pathology (e.g., pancreatitis, appendicitis, peritonitis, infarction), can be detected by CT. In contrast, plain radiographs of the abdomen often are unreliable, particularly in the presence of fluid-filled loops of bowel. A barium contrast study of the upper gastrointestinal tract and small intestine may be performed after CT to identify the site of partial obstruction more precisely or to provide an estimate of the gastrointestinal transit time. Barium contrast studies may suggest a diagnosis of achalasia, gastroparesis (missed by endoscopy), or neoplasm. In occasional cases, an enteroclysis study (where still performed), in which barium is infused directly into the small bowel via a nasoduodenal tube, may detect abnormalities missed on conventional barium studies. A higher diagnostic yield may be obtained by CT enterography. This radiologic procedure makes use of thin CT sections and large amounts of an oral neutral enteric contrast to allow better resolution of intestinal wall morphology and evaluation of individual loops of intestine without superimposition of the loops.50 Magnetic resonance enterography is an alternative to CT enterography and has the advantage of not exposing patients to radiation.51

Motility tests are useful for evaluating motor disorders, such as gastroparesis and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, that are relatively uncommon but important causes of nausea and vomiting. Various tests are available (see Chapters 48, 97, and 120).

Esophageal Manometry

Esophageal manometry is used to assess the motor activity of the esophagus. Patients with esophageal motility disorders occasionally may present with vomiting. Achalasia may produce pseudovomiting and progress unrecognized for years. Similarly, manometry may detect diffuse esophageal spasm and other motor disturbances of the smooth muscle portion of the esophagus that may present with or without characteristic symptoms (see Chapter 42).

Measurement of Gastric Emptying

Radioscintigraphy is the preferred and most accurate method of assessing gastric emptying. Ideally, dual markers (one for solids and one for liquids) should be used and the test performed with a dual-headed gamma camera. Alternative methods of assessing gastric emptying include gastric ultrasound to assess emptying of a liquid meal and the 13C breath test with octanoid acid, a fatty acid that is labeled with a stable isotope and incorporated into a test meal. The rate at which 13CO2 is exhaled reflects the rate of gastric emptying and subsequent duodenal absorption of the lipid marker (see Chapter 48).

Cutaneous Electrogastrography

Electrogastrography (EGG) with cutaneously placed electrodes identifies dysrhythmia (e.g., bradygastria or tachygastria) of the gastric pacemaker and changes in the frequency of pacemaker activity in response to feeding. Potential advantages of this test are its noninvasiveness and relative simplicity. Disadvantages include its unreliability because of poor signal and artifact and a lack of correlation with clinical symptoms; identified abnormalities may or may not be related to the patient’s symptoms. Certain EGG anomalies also may be secondary to nausea rather than the cause of nausea, although this issue is still subject to debate (see Chapter 48).

Gastrointestinal Manometry

Gastrointestinal manometry is probably the most reliable physiologic test for assessing motor disturbances of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Intraluminal pressure changes are recorded via a pressure-sensitive catheter at sites located in the antrum and small bowel. The test, however, is cumbersome, expensive, and technically challenging to perform and is available at only a few centers that specialize in gastrointestinal motility disorders. Manometry may distinguish myogenic from neurogenic forms of pseudo-obstruction and may help detect partial small bowel obstruction on the basis of wave pattern analysis (see Chapters 48, 119, and 120).

COMPLICATIONS

EMETIC INJURIES TO THE ESOPHAGUS AND STOMACH

Abrupt retching or vomiting episodes also may induce longitudinal mucosal and even transmural lacerations at the level of the gastroesophageal junction. When the lacerations are associated with acute bleeding and hematemesis, the clinical picture is described as the Mallory-Weiss syndrome (see Chapter 19). Boerhaave’s syndrome refers to spontaneous rupture of the esophageal wall, with free perforation and secondary mediastinitis, and carries a high mortality rate.52 It is more common in alcoholics, although esophageal rupture may develop in any person during vomiting (see Chapter 45).

SPASM OF THE GLOTTIS AND ASPIRATION PNEUMONIA

Spasm of the glottis and transient asphyxia may develop during vomiting as a result of irritation of the pharynx by acidic or bilious material. Similarly, vomiting during insertion of a nasogastric tube or during endoscopy, when the patient’s consciousness is diminished, or in an older person or patient with a depressed cough reflex, may be associated with aspiration of gastric contents into the bronchi, with resulting acute asphyxia and a subsequent risk of aspiration pneumonia.53 Aspiration is more likely to occur when the stomach contains food or enteric secretions than when it is empty.

TREATMENT

CORRECTION OF METABOLIC COMPLICATIONS

Patients with long-standing chronic vomiting are at risk of developing malnutrition. Therefore, enteral or parenteral feeding should be considered when the patient is not able to resume adequate oral nourishment after five to eight days. Although enteral nutrition is a good option, even orogastrojejunal catheters placed with guidewires may be dislodged during episodes of vomiting. For long-term treatment, home parenteral nutrition may be required (see Chapter 5).

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Drugs used to treat nausea and vomiting belong to one of two main categories, central antiemetic agents and peripheral prokinetic agents. Some drugs share both mechanisms of action, with variable predominance of one or the other.54–57

Central Antiemetic Agents

Dopamine D2 Receptor Antagonists

Benzamides

The main antiemetic effect of benzamides (e.g., metoclopramide, clebopride) is exerted centrally in the emetic center through antagonism of the dopamine D2 receptor. These agents also stimulate peripheral 5-HT4 receptors, thereby facilitating the release of acetylcholine and acting as antroduodenal prokinetic agents.6,57

Side effects limit the use of these drugs. Metoclopramide, if administered rapidly by the intravenous route, may cause acute restlessness and anxiety. Repeated oral administration may induce somnolence in some patients. In about 1% of treated patients, distressing extrapyramidal effects, including dystonic reactions and tremor, may appear and limit their use, particularly at high doses. Older patients are at particular risk of tardive dyskinesia.58 Metoclopramide may prolong the QT interval and thus has an arrhythmogenic potential.

The most common indications for these drugs are nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Because of their associated gastric prokinetic action, the drugs can be used for gastroparesis related to diabetes mellitus, prior vagotomy, and prior partial gastrectomy.59–61 The standard dose of metoclopramide is 10 to 20 mg three or four times daily orally or intravenously.

Benzimidazole Derivatives

Domperidone is the chief representative of this class of antiemetics.62 The drug crosses the blood-brain barrier poorly and acts primarily as a peripheral dopamine D2 receptor antagonist. It blocks the receptors centrally in the area postrema (which is partly outside the blood-brain barrier) and in the stomach, where D2 receptor inhibition decreases proximal gastric relaxation and facilitates gastric emptying.63,64 Although domperidone is a weaker antiemetic than metoclopramide, it may be particularly useful for the management of nausea and vomiting secondary to treatment with levodopa in Parkinson’s disease, because it antagonizes the proemetic side effects of levodopa without interfering with its antiparkinsonian action in brain centers protected by the blood-brain barrier. The standard dose is 10 to 20 mg three or four times daily orally. A review of the use of domperidone in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis has concluded that the drug is probably useful but has not been properly evaluated by well-designed controlled trials.63 Domperidone (as well as benzamides) may increase the release of prolactin and occasionally is associated with breast tenderness and galactorrhea.

Phenothiazines and Butyrophenones

The phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, perphenazine, prochlorperazine, promethazine, thiethylperazine) and butyrophenones (droperidol and haloperidol) also block D2 dopaminergic receptors and, in addition, block muscarinic M1 receptors. Phenothiazines also block histamine H1 receptors.65,66 These drugs tend to induce relaxation and somnolence and are generally used parenterally or as suppositories in patients with acute intense vomiting of central origin, as occurs with vertigo, migraine headaches, and motion sickness. They are also useful for patients with vomiting secondary to toxic agents and chemotherapy and after surgery.66,67 Droperidol also has been used as an adjunct to standard sedation during endoscopic procedures and, in combination with morphine, is used to reduce postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting.67,68 Safety concerns, including common extrapyramidal effects, however, have limited the use of all these agents.69

Antihistamines and Antimuscarinic Agents

Antihistamines and antimuscarinic agents act primarily by blocking histamine H1 receptors (cyclizine, diphenhydramine, cinnarizine, meclizine, hydroxyzine) and muscarinic M1 receptors (scopolamine) at a central level.70 Promethazine belongs to the phenothiazine class but acts as an antihistaminic H1 and antimuscarinic agent with strong sedative properties. Cyclizine and diphenhydrinate are used commonly to treat motion sickness and have been shown to decrease gastric dysrhythmia. Therefore, their antiemetic effect may be mediated in part by their peripheral action. A standard antiemetic dose of cyclizine is 50 mg, given three times daily orally or as a 100-mg suppository. The main indication is nausea and vomiting associated with motion sickness and vestibular disease. Cyclizine is useful for postoperative and other forms of acute vomiting.71 Some of these drugs are also used as antipruritic agents. Drowsiness is the major limiting side effect, particularly for the older agents, but this effect may be advantageous in the treatment of acute vomiting. The anticholinergic effects are potentially troublesome in patients with glaucoma, prostatic hyperplasia, and asthma.

Serotonin Antagonists

Serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (ondansetron, granisetron, dolasetron, tropisetron) are potent antiemetics that selectively block 5-HT3 receptors in the emetic center and in gastric wall receptors that relay afferent emetic impulses through the vagus nerve.72 In addition to their antiemetic effect, they have a modest gastric prokinetic action.73 The main indication for this class of drugs is nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy or radiation therapy or following surgery.5,74–76 Ondansetron appears to be safe in pregnancy.77 Ondansetron may be given as a single dose of 8 to 32 mg, intravenously in a dose of 0.15 mg/kg every eight hours, or orally in a dose of 12 to 24 mg every 24 hours, in three divided doses. Headache is a common side effect.

Glucocorticoids

The antiemetic mechanism of glucocorticoids is not well understood. It may relate to inhibition of central prostaglandin synthesis, release of endorphins, or altered synthesis or release of serotonin. The principal indication is treatment of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period or as a result of chemotherapy or radiation.78–80 Glucocorticoids also may be used to reduce cerebral edema and hence alleviate vomiting secondary to increased intracranial pressure. Dexamethasone is the formulation used acutely, in doses ranging from 8 to 20 mg intravenously and 4 mg every six hours orally. Side effects are uncommon because treatment is usually administered for short periods. In diabetic patients, however, careful monitoring of blood glucose levels is required. In patients with a history of peptic ulcer or with a gastroenteric anastomosis, concurrent administration of a gastric antisecretory agent is advisable. In practice, dexamethasone often is used in combination with another antiemetic agent, such as metoclopramide or a 5-HT3 antagonist.81

Cannabinoids

Synthetic cannabinoids are becoming part of the standard therapeutic ornamentation.82 Two oral formulations are available, nabilone and dronabinol. Both are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting refractory to conventional antiemetic therapy. The combination of a dopamine antagonist and a cannabinoid may be particularly effective in preventing nausea that has a major negative impact on a patient’s quality of life.83,84 Mood-enhancing properties make cannabinoids attractive to patients, but these drugs are potentially more toxic than conventional antiemetic agents. Hypotension and psychotropic reactions are relatively common side effects. These drugs should be used with caution in older adults and in patients with a history of mental illness.85,86

Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonists

NK-1 receptor antagonists, which inhibit substance P/NK-1, are potent antiemetic agents. Two formulations are available, aprepitant (oral) and fosaprepitant (parenteral), and several others (e.g., casopitant, vestipitant, netupitant) are undergoing evaluation. These drugs appear to provide better protection against postoperative vomiting but not nausea when compared with 5-HT3 antagonists.87 NK-1 receptor antagonists may be particularly useful when combined with other drugs such as 5-HT3 antagonists and dexamethasone and are approved by the FDA for use in preventing vomiting in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy.88

Adjuvant Agents and Therapies

Patients with acute nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery often have anxiety, which may exacerbate their symptoms. Therefore, the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines such as lorazepam and alprazolam may potentiate the antiemetic action of agents such as 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and glucocorticoids that are devoid of psychotropic effects. Acupuncture, acustimulation, and acupressure also have been shown to decrease the nausea associated with motion sickness induced by illusory self-motion and nausea associated with cancer chemotherapy.89–91

Gastric Prokinetic Agents

Serotonin 5-HT4 Receptor Agonists

Cisapride and cinitapride are drugs in the benzamide class that share the peripheral 5-HT4 agonist effect of metoclopramide (also a benzamide) without the dopamine D2 antagonist action that is primarily responsible for the potentially troublesome central side effects of metoclopramide. Although cisapride and cinitapride lack central depressant effects, they retain antiemetic properties because of some 5-HT3 properties.92 Cisapride is a potent gastric prokinetic agent at doses of 5 to 20 mg three to four times daily in adults. Dosing adjustments are not needed in older adult patients. Unfortunately, cisapride carries a significant risk of precipitating serious cardiac ventricular arrhythmias, especially in patients concomitantly taking drugs that prolong the QT interval.92 Thus, cisapride has been withdrawn from the market in many countries, although in others, including the United States, it may still be prescribed with certain restrictions.

Cinitapride is analogous to cisapride, but at a dose of 1 mg orally three times daily has not been associated with cardiac arrhythmias. It is not yet available in the United States.93

Tegaserod, a partial 5-HT4 agonist with prokinetic action, was considered potentially useful for the treatment of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia but had to be withdrawn from the market because of reported cardiovascular events; it may be obtained only under exceptional circumstances.94 The main indication for 5-HT4 agonist drugs is the management of nausea and vomiting associated with gastroparesis, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, and functional dyspepsia.95–97

Motilin Receptor Agonists

Motilin receptor agonists include the antibiotic erythromycin and other agents—none of which is commonly available—that act as motilin receptor ligands on smooth muscle cells and enteric nerves. The pharmacodynamic effects in humans are dose-dependent. At low doses (0.5 to 1 mg/kg as an intravenous bolus), erythromycin induces sweeping gastric and intestinal peristaltic motor activity that resembles phase III of the interdigestive migrating motor complex but may empty the stomach inefficiently (see Chapters 48 and 97).98 At higher doses of 200 mg intravenously used in clinical practice, antral activity becomes intense and empties the stomach rapidly, although the burst of motility does not always migrate down the small intestine.99,100 A simultaneous increase in small bowel contractions may induce abdominal cramps and diarrhea. Curiously, when used clinically as an antibiotic, erythromycin may cause nausea and vomiting.

In clinical practice, erythromycin may be used to treat acute nausea and vomiting associated with gastroparesis (diabetic, postsurgical, or idiopathic)92,100 and to clear the stomach of retained food, secretions, and blood prior to endoscopy. Erythromycin may be administered intravenously in boluses of 200 to 400 mg every four to five hours. The lower doses are more appropriate for patients with pseudo-obstruction, which is associated with reduced interdigestive sweeping motor activity in the small bowel.

Ghrelin is a peptide structurally and functionally related to motilin that acts to accelerate postprandial gastric emptying. Ghrelin receptor agonists may have a future therapeutic role as prokinetic agents for the treatment of gastroparesis.101,102

GASTRIC ELECTRICAL STIMULATION

Gastric pacing involves application of high-energy currents that entrain the gastric slow waves and generate phasic contractions. This technique may achieve correction of gastroparesis and amelioration of nausea and vomiting but requires external energy sources that limit the autonomy of the patient and is not practical. An alternative approach, gastric neurostimulation, delivers brief low-energy impulses to the stomach with the use of an implantable neurostimulator similar to devices used to control chronic pain. The gastric neurostimulator does not entrain slow wave activity and produces little or no acceleration of gastric emptying, but it appears to relax proximal gastric tone and to produce significant improvement in nausea and vomiting, as well as the patient’s nutritional status.103 The device is approved for humanitarian use only by the FDA. Gastric neurostimulation, however, is not without risk, and commonly reported complications include electrode dislodgement, infection, and bowel obstruction. The device may be recommended with caution for long-standing (at least one year’s duration) refractory gastroparesis.104,105

Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Review article: Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:269-84. (Ref 40.)

Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: Cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. 2003;53:1566. (Ref 42.)

Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, et al. IMPACT Investigators. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441-51. (Ref 21.)

Einarson A, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, et al. The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A prospective comparative study. BJOG. 2004;111:940-3. (Ref 77.)

Flake ZA, Scalley RD, Bailey AG. Practical selection of antiemetics. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1169-74. (Ref 54.)

Gourcerol G, Leblanc I, Leroi AM, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation in medically refractory nausea and vomiting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:29-35. (Ref 105.)

Gralla RJ, Osoba D, Kris MG, et al. Recommendations for the use of antiemetics: Evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2971-94. (Ref 55.)

Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261-8. (Ref 18.)

Imperato F, Canova I, Basili R, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum—etiology and treatment. Clin Ter. 2003;154:337-40. (Ref 34.)

Jewell D. Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Clin Evid. 2003:1561-70. (Ref 28.)

Malagelada JR. Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2000;3:335-40. (Ref 24.)

O’Brien MD, Bruce BK, Camilleri M. The rumination syndrome: Clinical features rather than manometric diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1024-9. (Ref 49.)

Pandolfino JE, Howden CW, Kahrilas PJ. Motility modifying agents and management of disorders of gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology. 2000;2(Suppl 1):S32-47. (Ref 60.)

Sewell DD, Jeste DV. Metoclopramide-associated tardive dyskinesia. An analysis of 67 cases. Arch Fam Med. 1992;1:271-8. (Ref 58.)

Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-33. (Ref 63.)

Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-79. (Ref 38.)

1. Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:263-86.

2. Fraga X, Malagelada JR. Nausea and vomiting. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2002;4:241-50.

3. Hornby PJ. Central neurocircuitry associated with emesis. Am J Med. 2001;111(Suppl 8A):S106-12.

4. Bruntos L. Agents affecting gastrointestinal water flux and motility; emesis and antiemetics: Bile acids and pancreatic enzymes. In: Hardman J, Limbird L, editors. The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:928.

5. Cubeddu LX, Hoffmann IS, Fuenmayor NT, Finn AL. Efficacy of ondansetron (GR 38032F) and the role of serotonin in cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:810-16.

6. McCallum RW, Albibi R. Metoclopramide. Pharmacology and clinical application. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:86-95.

7. Golding JF, Stott JR. Comparison of the effects of a selective muscarinic receptor antagonist and hyoscine (scopolamine) on motion sickness, skin conductance and heart rate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:633-7.

8. Van Sickle MD, Oland LD, Ho W, et al. Cannabinoids inhibit emesis through CB1 receptors in the brainstem of the ferret. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:767-74.

9. Coutts AA, Izzo AA. The gastrointestinal pharmacology of cannabinoids: An update. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;12:572-9.

10. Duncan M, Davison JS, Sharkey RA. Review article: Endocannabinoids and their receptors in the enteric nervous system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:667-83.

11. Lumsden K, Holden WS. The act of vomiting in man. Gut. 1969;10:173-9.

12. Thompson DG, Malagelada JR. Vomiting and the small intestine. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:1121-5.

13. Horowitz M, Su YC, Rayner CK, Jones KL. Gastroparesis: Prevalence, clinical significance and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:805-13.

14. Mann SD, Danesh BJ, Kamm MA. Intractable vomiting due to a brainstem lesion in the absence of neurological signs or raised intracranial pressure. Gut. 1998;42:875-7.

15. Teague WJ, Ackroyd R, Watson DI, Devitt PG. Changing patterns in the management of gastric volvulus over 14 years. Br J Surg. 2000;87:358-61.

16. Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. AGA technical review on intestinal ischemia. American Gastrointestinal Association. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:954-68.

17. Herrstedt J. Risk-benefit of antiemetics in prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3:231-48.

18. Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261-8.

19. Hoebe CJ, Vennema H, de Roda Husman AM, van Duynhoven YT. Norovirus outbreak among primary schoolchildren who had played in a recreational water fountain. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:699-705.

20. Catenoix H, Isnard J, Guenot M, et al. The role of the anterior insular cortex in ictal vomiting: A stereotactic electroencephalography study. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:560-3.

21. Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, et al. IMPACT Investigators. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441-51.

22. Muir JC, von Gunten CF. Abdominal cancer, nausea, and vomiting. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:391-4.

23. Borowitz SM, Sutphen JL. Recurrent vomiting and persistent gastroesophageal reflux caused by unrecognized constipation. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43:461-6.

24. Malagelada JR. Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2000;3:335-40.

25. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology) Practice Bulletin: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:803-14.

26. Koren G, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, Wolpin J. Recall bias of the symptoms of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:485-8.

27. Roberts NJ, Bowskill RJ, Rafferty PG. Self-induced hyperemesis in pregnancy. J R Soc Med. 2004;97:128-9.

28. Jewell D. Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Clin Evid. 2003:1561-70.

29. Koren G, Maltepe C. Pre-emptive therapy for severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:530-3.

30. Einarson A, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, et al. The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A prospective comparative study. BJOG. 2004;111:940-3.

31. Harker N, Montgomery A, Fahey T. Treating nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: Case outcome. BMJ. 2004;328:503-4.

32. Markose MT, Ramanathan K, Vijayakumar J. Reduction of nausea, vomiting, and dry retches with P6 acupressure during pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;85:168-9.

33. Smith C, Crowther C, Willson K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ginger to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:639-45.

34. Imperato F, Canova I, Basili R, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum—etiology and treatment. Clin Ter. 2003;154:337-40.

35. Vaisman N, Kaidar R, Levin I, Lessing JB. Nasojejunal feeding in hyperemesis gravidarum—a preliminary study. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:53-7.

36. Czeizel AE, Puho E. Association between severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and lower rate of preterm births. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18:253-9.

37. Moldenhauer JS, O’Brien JM, Barton JR, Sibai B. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy associated with pancreatitis: A life-threatening complication. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:502-5.

38. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-79.

39. Li BU, Misiewicz L. Cyclic vomiting syndrome: A brain-gut disorder. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:997-1019.

40. Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Review article: Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:269-84.

41. Moskowitz MA. Neurogenic versus vascular mechanisms of sumatriptan and ergot alkaloids in migraine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:307-11.

42. Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: Cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Gut. 2003;53:1566.

43. Ludvigsson J. Propranolol in treatment of migraine in children [letter]. Lancet. 1973;6(2):799.

44. Prakash C, Clouse RE. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: Clinical features and response to tricyclic antidepressants. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2855-60.

45. Kaiser GC, McKain JM, Shumacker HB. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Surgery. 1960;110:133-40.

46. Shandling B. The so-called superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1976;130:1371-3.

47. Amarnath RP, Abell TL, Malagelada JR. The rumination syndrome in adults. A characteristic manometric pattern. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:513-8.

48. Olden KW. Rumination. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:351-8.

49. O’Brien MD, Bruce BK, Camilleri M. The rumination syndrome: Clinical features rather than manometric diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1024-9.

50. Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, et al. CT enterography as a diagnosis in evaluating small bowel disorders: Review of clinical experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics. 2006;26:641-57.

51. Fidler J. MR imaging of the small bowel. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:317-31.

52. Atallah FN, Riu BM, Nguyen LB, et al. Boerhaave’s syndrome after postoperative vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1164-6.

53. Osterhoudt KC, Durbin D, Alpern ER, Henretig FM. Risk factors for emesis after therapeutic use of activated charcoal in acutely poisoned children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:806-10.

54. Flake ZA, Scalley RD, Bailey AG. Practical selection of antiemetics. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1169-74.

55. Gralla RJ, Osoba D, Kris MG, et al. Recommendations for the use of antiemetics: Evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2971-94.

56. Kazemi-Kjellberg F, Henzi I, Tramer MR. Treatment of established postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol. 2001;1:2.

57. MacGregor EA. Anti-emetics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;17(Suppl 1):S22-5.

58. Sewell DD, Jeste DV. Metoclopramide-associated tardive dyskinesia. An analysis of 67 cases. Arch Fam Med. 1992;1:271-8.

59. Jokela R, Koivuranta M, Kangas-Saarela T, et al. Oral ondansetron, tropisetron or metoclopramide to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting: A comparison in high-risk patients undergoing thyroid or parathyroid surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:519-24.

60. Pandolfino JE, Howden CW, Kahrilas PJ. Motility modifying agents and management of disorders of gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterology. 2000;2(Suppl 1):S32-47.

61. Dumitrascu DL, Weinbeck M. Domperidone versus metoclopramide in the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:316-17.

62. Brogden RN, Carmine AA, Heel RC, et al. Domperidone. A review of its pharmacological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of chronic dyspepsia and as antiemetic. Drugs. 1982;24:360-400.

63. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-33.

64. Franzese A, Borrelli O, Corrado G, et al. Domperidone is more effective than cisapride in children with diabetic gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:951-7.

65. Sriram K, Schumer W, Ehrenpreis S, et al. Phenothiazine effect on gastrointestinal tract function. Am J Surg. 1979;137:87-91.

66. Steinbrook RA, Gosnell JL, Freiberger D. Prophylactic antiemetics for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A comparison of perphenazine, droperidol plus ondansetron, and droperidol plus metoclopramide. J Clin Anesth. 1998;10:494-8.

67. Hechler A, Neumann S, Jehmlich M, et al. A small dose of droperidol decreases postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults but cannot improve an already excellent patient satisfaction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:501-6.

68. Wille RT, Barnett JL, Chey WD, et al. Routine droperidol pre-medication improves sedation for ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:362-6.

69. Gan TJ. “Black box” warning on droperidol: Report of the FDA convened expert panel. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1809.

70. O’Brien CM, Titley G, Whitehurst P. A comparison of cyclizine, ondansetron and placebo as prophylaxis against postoperative nausea and vomiting in children. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:707-11.

71. Turner KE, Parlow JL, Avery ND, et al. Prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting with oral, long-acting dimenhydrinate in gynecologic outpatient laparoscopy. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1660-4.

72. Camilleri M, von der Ohe MR. Drugs affecting serotonin receptors. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;8:301-19.

73. Akkermans LM, Vos A, Hoekstra A, et al. Effect of ICS 205-930 (a specific 5-HT3 receptor antagonist) on gastric emptying of a solid meal in normal subjects. Gut. 1988;29:1249-52.

74. Tonato M, Roila F, Del Favero A, Ballatori E. Methodology of trials with antiemetics. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:281-6.

75. Markman M. Progress in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cleve Clin J Med. 2002;69:609-10. 612, 615-17

76. Golembiewski JA, O’Brien D. A systematic approach to the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2002;17:364-76.

77. Einarson A, Maltepe C, Navioz Y, et al. The safety of ondansetron for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: A prospective comparative study. BJOG. 2004;111:940-3.

78. Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, et al. Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62-71.

79. Henzi I, Walder B, Tramer MR. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:186-94.

80. Ioannidis JP, Hesketh PJ, Lau J. Contribution of dexamethasone to control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A meta-analysis of randomized evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3409-22.

81. Habib AS, El-Moalem HE, Gan TJ. The efficacy of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists combined with droperidol for PONV prophylaxis is similar to their combination with dexamethasone. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:311-19.

82. Mechoulam R, Hanu L. The cannabinoids: An overview. Therapeutic implications in vomiting and nausea after cancer chemotherapy, in appetite promotion, in multiple sclerosis and in neuroprotection. Pain Res Manag. 2001;6:67-73.

83. Slatkin NE. Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: beyond prevention of acute emesis. J Support Oncol. 2007;5(Suppl 3):1-9.

84. Machado Rocha FC, Stéfano SC, De Cássia Haiek R, et al. Therapeutic use of Cannabis sativa on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting among cancer patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008;17:431-43.

85. Cunningham D, Bradley CJ, Forrest GJ, et al. A randomized trial of oral nabilone and prochlorperazine compared to intravenous metoclopramide and dexamethasone in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy regimens containing cisplatin or cisplatin analogues. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:685-9.

86. Tramèr MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, et al. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: Quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:16-21.

87. Apfel CC, Malhotra A, Leslie JB. The role of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21:427-32.

88. Navari RM. Inhibiting substance p pathway for prevention of chemotherapy-induced emesis: Preclinical data, clinical trials of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists. Support. Cancer Ther. 2004;1:89-96.

89. Streitberger K, Diefenbacher M, Bauer A, et al. Acupuncture compared to placebo-acupuncture for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis: A randomised placebo-controlled patient and observer blind trial. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:142-9.

90. Habib AS, White WD, Eubanks S, et al. A randomized comparison of a multimodal management strategy versus combination antiemetics for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:77-81.

91. Antonarakis ES, Hain RD. Nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy: Drug management in theory and in practice. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:877-80.

92. Annese V, Lombardi G, Frusciante V, et al. Cisapride and erythromycin prokinetic effects in gastroparesis due to type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:599-603.

93. Tonini M, De Ponti F, Di Nucci A, et al. Review article: Cardiac adverse effects of gastrointestinal prokinetics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1585-91.

94. Degen L, Matzinger D, Merz M, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT4 receptor partial antagonist, accelerates gastric emptying and gastrointestinal transit in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1745-51.

95. Peeters TL. Erythromycin and other macrolides as prokinetic agents. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1886-99.

96. Horowitz M, Jones KL, Harding PE, Wishart JM. Relationship between the effects of cisapride on gastric emptying and plasma glucose concentration in diabetic gastroparesis. Digestion. 2002;65:41-6.

97. Camilleri M, Brown ML, Malagelada JR. Impaired transit of chyme in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Correction by cisapride. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:619-26.

98. Medhus AW, Bondi J, Gaustad P, Husebye E. Low-dose intravenous erythromycin: Effects on postprandial and fasting motility of the small bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:233-40.

99. Lin HC, Sanders SL, Gu YG, Doty JE. Erythromycin accelerates solid emptying by inducing antral contractions and improved gastroduodenal coordination. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:124-8.

100. Tack J, Janssens J, Vantrappen G, et al. Effect of erythromycin on gastric motility in controls and in diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:72-9.

101. Peeters TL. Potential of ghrelin as a therapeutic approach for gastrointestinal motility disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:553-8.

102. Levin F, Edholm T, Schmidt PT, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric emptying and hunger in normal-weight humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3296-302.

103. Abell T, McCallum R, Hocking M, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation for medically refractory gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:421-8.

104. Lin Z, Forster J, Sarosiek I, McCallum RW. Treatment of diabetic gastroparesis by high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1071-6.

105. Gourcerol G, Leblanc I, Leroi AM, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation in medically refractory nausea and vomiting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:29-35.