Chapter 5 NAUSEA AND VOMITING

INTRODUCTION

Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms with a wide array of possible causes. Nausea describes the unpleasant subjective sensations that precede vomiting. During nausea, reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach is frequent, possibly due to increased tone of the duodenum and proximal jejunum, although this is not always present. Concurrently, gastric tone is reduced and gastric peristalsis is diminished or absent. It is important to distinguish between four distinct symptoms, namely retching, vomiting, regurgitation and rumination, that superficially may appear similar (Table 5.1). In particular, vomiting involves expulsion of gastric contents through the mouth via forceful, sustained contraction of the abdominal muscles and diaphragm when the pylorus is contracted. Occasionally, vomiting is associated with hypersalivation and defecation; cardiac dysrhythmias may rarely occur.

TABLE 5.1 Definitions of terminology associated with nausea and vomiting

| Nausea: The unpleasant sensation of the imminent need to vomit, usually referred to the throat or epigastrium; a sensation that may or may not ultimately lead to the act of vomiting. |

| Retching: Spasmodic respiratory movements against a closed glottis with contractions of the abdominal musculature without expulsion of any gastric contents, referred to as ‘dry heaves’. |

| Vomiting: Forceful oral expulsion of gastric contents associated with contraction of the abdominal and chest wall musculature. |

| Regurgitation: The act by which food is brought back into the mouth without the abdominal and diaphragmatic muscular activity that characterises vomiting. |

| Rumination: Chewing and swallowing of regurgitated food that has come back into the mouth through an unconscious voluntary increase in abdominal pressure within minutes of eating or during eating. |

| Anorexia: Loss of desire to eat, that is, a true loss of appetite. |

| Sitophobia: Fear of eating because of subsequent or associated discomfort. |

| Early satiety: The feeling of being full after eating an unusually small quantity of food. |

Adapted from Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:263–86.

PATHOGENESIS

Neurotransmission in the vomiting centre and CTZ appears to be mediated via dopaminergic, serotonergic, muscarinic and histaminergic receptors, and pharmacological therapies have been developed targeting each of these (see later).

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The differential diagnosis of nausea and/or vomiting is extensive and is presented in Table 5.2. The major causes include infection, medications (particularly chemotherapeutic agents) and toxins, central nervous system pathology, organic gastrointestinal disorders, endocrine and metabolic disorders including pregnancy, systemic illnesses, psychiatric disease, postoperatively and functional gastrointestinal disorders including the cyclical vomiting syndrome.

| Medications and toxic aetiology |

Adapted from Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:263–86.

Important aspects in the history that may assist in identifying the cause include:

Physical examination should be directed by the history obtained, however, abdominal examination is essential and should include assessing for tenderness with some emphasis on localisation, presence or absence of bowel sounds and a succussion splash, evidence of previous abdominal surgery, hernias and masses. Subsequently several additional areas may need review including, but not limited to, assessment for lymphadenopathy, central or peripheral neurological deficits, evidence of connective tissue disease or thyroid dysfunction, and review of fingernails and tooth enamel for signs of acid damage from recurrent vomiting.

Investigations

The commonest causes of gastroparesis are idiopathic (possibly post-viral) and diabetes mellitus. Systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, dermatomyositis and amyloidosis may also cause gastroparesis, which is also seen after vagotomy and in association with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroparesis results in abnormal gastric emptying, however this also may be seen in up to 40% of patients with functional gastroduodenal disorders (Table 5.3).

| Diagnostic criteria*for chronic idiopathic nausea |

| Must include all of the following: |

* Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Abnormal gastric emptying may be assessed using a radionuclide gastric emptying study in which serial images of the retention or disappearance of a radiolabelled meal from the stomach are captured by a γ-camera. Solid meals are more sensitive for detecting gastroparesis compared with liquid meals. Delayed gastric emptying is considered present if the gastric retention at 4 hours is greater than 40% of the radiolabelled meal (sensitivity 100%, specificity 70%).

Electrogastrography (EGG) measures the electrical activity of the stomach with surface electrodes in both the fasting and the postprandial states. The normal pacemaker rhythm of gastric myoelectrical activity is three cycles per minute. A reduction in or absence of the expected postprandial increase in the EGG amplitude correlates with delayed gastric emptying and antral hypomotility. Unfortunately, gastric dysrhythmias (both bradygastria and tachygastria) have been observed in the absence of altered gastric emptying, limiting its application to clinical practice.

Functional vomiting

Once common organic and psychiatric causes for chronic nausea and vomiting have been excluded, functional nausea and vomiting disorders need to be considered as a possible diagnosis. These are summarised in Table 5.3. The essential difference between functional and cyclic vomiting disorders is the pattern and frequency of vomiting; functional vomiting occurs at least weekly (on average), whereas cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) consists of stereotypical episodes of vomiting regarding onset (acute) and duration (less than 1 week), with the additional requirement for three or more discrete episodes in the prior year and the absence of nausea and vomiting between episodes. CVS is commonly associated with irritable bowel syndrome, motion sickness and, less frequently, migraine; family histories of these conditions are present in approximately 50% of patients.

MANAGEMENT

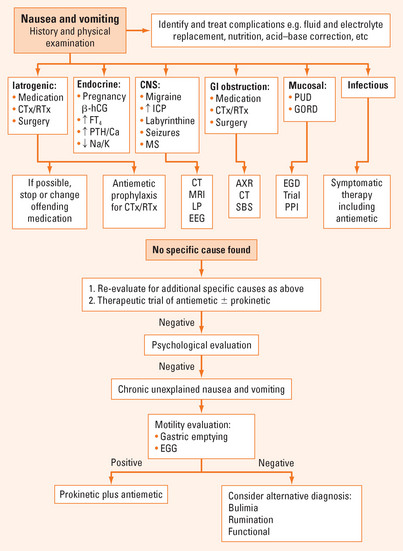

Initial management should include appropriate replacement of fluids either orally or intravenously as tolerated, with correction of any electrolyte (e.g. potassium, bicarbonate) or nutritional deficiencies that may have resulted from vomiting itself or the food aversion that may accompany these symptoms (Figure 5.1). Symptomatic management of the nausea and/or vomiting may be required while the underlying cause of the symptoms is identified and eliminated where possible. Placement of a nasogastric tube may also be required to relieve gastric distension if gastrointestinal obstruction is the cause.

FIGURE 5.1 Suggested algorithm for assessment and management of nausea and vomiting.

Adapted from Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:263–86.

Pharmacological

A variety of agents display antiemetic properties including serotonin (5-HT) antagonists, anticholinergics, H1-receptor antagonists, phenothiazines, butyrophenones, benzamides, which also have prokinetic effects, neurokinin-1 antagonists, cannabinoids, and adjunctive agents such as benzodiazepines and corticosteroids. Examples of these agents are given in Table 5.4, which also outlines their common uses.

TABLE 5.4 Pharmacological agents effective in treating organic nausea and vomiting

| Agent | Use | Formulation |

| Phenothiazines e.g. promethazine, prochlorperazine | PONV, PCNV | Oral, PR, IV |

| Severe nausea and vomiting | ||

| Vertigo, motion sickness, migraine | ||

| 5-HT3 antagonists e.g. ondansetron, tropisetron | PONV, PCNV | Oral, wafers, IV |

| Prokinetics e.g. metoclopramide, domperidone | Gastroparesis PONV, PCNV | Oral, IV (not domperidone) |

| Butyrophenones e.g. droperidol, haloperidol | Anticipatory and acute chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting PONV | Oral, IM, IV |

| Benzodiazepines e.g. lorazepam | Adjunctive in treatment of chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting | Oral, S/L, IV |

| Neurokinin-1 antagonists | Acute and delayed PCNV, adjunct in combination with 5-HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone | Oral |

| Corticosteroids e.g. dexamethasone | Adjunctive in treatment of chemotherapy related nausea and vomiting | Oral, IV |

5-HT = 5-hydroxytryptamine or serotonin; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; PCNV = post-chemotherapy nausea and vomiting; PONV = post-operative nausea and vomiting; PR = per rectum; S/L = sublingual.

Treatment of functional nausea and vomiting

Functional vomiting may require nutritional and electrolyte support and, once again, individual patients may respond to empiric antiemetic use and TCA therapy.

Severe episodes of cyclic vomiting may require hospitalisation for sedation and intravenous fluid and electrolyte support. If episodes are frequent or severe enough, particularly if a history of migraine is present, consideration should be given to daily treatment with agents including amitriptyline, pizotifen, cyproheptadine, phenobarbitone or propranolol; these may reduce the frequency of or eliminate episodes. Any identifiable factors known to trigger episodes, such as specific foods, emotional factors or physical stressors, should be avoided. If there is a recognisable prodrome, the episodes may potentially be aborted with early administration of ondansetron or a long-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam, which is beneficial for its anxiolytic, sedative and antiemetic effects. Deep sleep for several hours may prevent the episode. Early acid suppression may protect oesophageal mucosa and dental enamel from damage from acidic gastric contents.

Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519-1526.

Li BU, Misiewicz L. Cyclic vomiting syndrome: a brain–gut disorder. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:997-1019.

Prakash C, Clouse RE. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: clinical features and response to tricyclic antidepressants. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2855-2860.

Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:263-286.

Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479.