Chapter 1 Naturopathic case taking

NATUROPATHIC PHILOSOPHY AND PRINCIPLES

For naturopaths, the patient-centred approach to case taking with its emphasis on rapport, empathy and authenticity is a vital part of the healing process. It is based not just on current accepted health practices but on the philosophy and principles that have underpinned naturopathy since its beginnings. This chapter examines how to establish and maintain a therapeutic relationship with patients through the process of a holistic consultation in the light of these values and practices. This chapter also presents a model of the structure and process of holistic case taking that will facilitate this consultation and provide both patient and naturopath with the knowledge and insight needed for healing and wellness.

Historical precursors

Having a philosophy by which to practice gives a clearer understanding of what constitutes good health, how illness is caused, what the role of the practitioner should be, and the type of treatments that should be given.1 Naturopathy has a loosely defined set of principles that have arisen from three interrelated philosophical sources. The first main source is the historical precursors of eclectic health-care practices that formed naturopathy in the 19th and 20th centuries.2 Allied to this are two other essential philosophical concepts intertwined with the historical development of naturopathy: vitalism3,4 and holism5.

The tenets of naturopathic philosophy have developed from its chequered historical background, which includes the traditions of Hippocratic health, herbal medicine, homoeopathy, nature cure, hydrotherapy, dietetics and manipulative therapies.6 In modern times naturopathic philosophy has borrowed from the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s that fostered independence from authoritative structures and challenged the dependency upon technology and drugs for health care. These social movements emphasised a holistic approach to the environment and ecology with a yearning for health care that was natural and promoted self-reliance harking back to late 19th-century principles of nature care philosophy.7 Naturopathy also borrowed from other counterculture movements and began to be suffused with New Age themes of transpersonal and humanistic psychology, spirituality, metaphysics and new science paradigms.8 Since the 1980s naturopathy has increasingly used scientific research to increase understanding of body systems and validate treatments.9,10

From this variety of sources, naturopathy has consolidated a number of core principles. These principles have had many diverse adherents and an eclectic variety of blended philosophies. Notwithstanding this, there are key concepts within naturopathy that are agreed upon and are flexible enough to accommodate a broad range of styles in naturopathic practice.11

The historical precursors of naturopathy emphasise the responsibility of the patient in following a healthy lifestyle with a balance of work, recreation, exercise, meditation and rest; eating healthily, and having fresh air, water and sunshine; regular detoxification and cleansing; healthy emotions within healthy relationships; an ethical life; and a healthy environment. These views highlight the fact that each patient is unique and, in light of this, naturopathic treatments for each patient are tailored to addressing the individual factors that cause their ill health. An essential part of a holistic consultation is the education of the patient to promote healthy living, self-care, preventive medicine and the unique factors affecting their vitality.12

Vitalism

A fundamental belief of naturopathy is that ill health begins with a loss of vitality. Health is positive vitality and not just an absence of medical findings of disease. Health is restored by raising the vitality of the patient, initiating the regenerative capacity for self-healing. The vital force is diminished by a range of physical, mental, emotional, spiritual and environmental factors.13

Vitalism is the belief that living things depend on the action of a special energy or force that guides the processes of metabolism, growth, reproduction, adaptation and interaction.14 This vital force is capable of interactions with material matter, such as a person’s biochemistry, and these interactions of the vital force are necessary for life to exist. The vital force is non-material and occurs only in living things. It is the guiding force that accounts not only for the maintenance of life, but for the development and activities of living organisms such as the progression from seed to plant, or the development of an embryo to a living being.15

The vital force is seen to be different from all the other forces recognised by physics and chemistry. And, most importantly, living organisms are more than just the effects of physics and chemistry. Vitalists agree with the value of biochemistry and physics in physiology but claim that such sciences will never fully comprehend the nature of life. Conversely, vitalism is not the same as a traditional religious view of life. Vitalists do not necessarily attribute the vital force to a creator, a god or a supernatural being, although vitalism can be compatible with such views. This is considered a ‘strong’ interpretation of vitalism. Naturopaths use a ‘moderate’ form of vitalism: vis medicatrix naturae, or the healing power of nature.1

Vis medicatrix naturae defines health as good vitality where the vital force flows energetically through a person’s being, sustaining and replenishing us, whereas ill health is a disturbance of vital energy.3 While naturopaths agree with modern pathology about the concepts of disease (cellular dysfunction, genetics, accidents, toxins and microbes), naturopathic philosophy further believes that a person’s vital force determines their susceptibility to illness, the amount of treatment necessary, the vigour of treatment and the speed of recovery.16 Those with poor vitality will succumb more quickly, require more treatment, need gentler treatments and take longer to recover.17

Vis medicatrix naturae sees the role of the practitioner as finding the cause (tolle causum) of the disturbance of vital force. The practitioner must then use treatments that are gentle, safe, non-invasive techniques from nature to restore the vital force; and to use preventative medicine by teaching (docere—doctor as teacher) the principles of good health.18

Vitality and disease

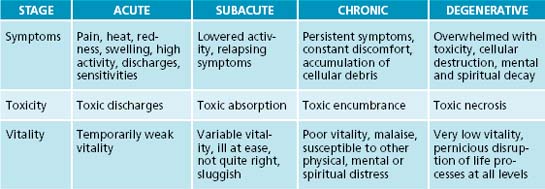

Vitalistic theory merges with naturopathy in the understanding of how disease progresses (see Table 1.1). The acute stages of disease have active, heightened responses to challenges within the body systems. When the vital force is strong it reacts to an acute crisis by mobilising forces within the body to ‘throw off’ the disease.17 The effect on vitality is usually only temporary as the body reacts with pain, redness, heat and swelling. If this stage is not dealt with appropriately where suppressive medicines are used the vital force is weakened and acute illnesses begin to become subacute. This is where there are less activity, less pain and less reaction within the body, accompanied by a lingering loss of vitality, mild toxicity and sluggishness. The patient begins to feel more persistently ‘not quite right’ but nothing will show up on medical tests and, in the absence of disease, the patient will be declared ‘healthy’ in biomedical terms. If the patient continues without addressing their health and lifestyle in a holistic way they can begin to

EFFECTS ON HEALTH AND VITALITY

experience chronic diseases where there are long-term, persistent health problems. This is highlighted by weakened vitality, poor immune responses, toxicity, metabolic sluggishness, and the relationships between systems both within and outside the patient becomes dysfunctional. The final stage of disease is destructive where there are tissue breakdown, cellular dysfunction, low vitality and high toxicity.19

In traditional naturopathic theory the above concepts emphasise the connections between lowered vitality and ill health. Traditional naturopathic philosophy also emphasises that the return of vitality through naturopathic treatment will bring about healing. The stages of this healing are succinctly summarised by Dr Constantine Hering, a 19th-century physician, and these principles of healing are known as Hering’s Law of Cure.19,20

HERING’S LAW OF CURE

Holism

Another essential principle of naturopathy developed from its eclectic history is the importance of a holistic perspective to explore, understand and treat the patient. Holism comes from the Greek word holos, meaning whole.21,22 The concept of holism has a more formal description in general philosophy and has three main beliefs.23 First, it is important to consider an organism as a whole. The best way to study the behaviour of a complex system is to treat it as a whole and not merely to analyse the structure and behaviour of its component parts. It is the principles governing the behaviour of the whole system rather than its parts that best elucidate an understanding of the system.

Thirdly, the important characteristics of an organism do not occur at the physical and chemical levels but at a higher level where there is a holistic integration of systems within the whole being. There are important interrelations that define the systems and these may be completely missed in a ‘parts-only perspective’. These interrelations are completely independent of the parts. For instance, the digestive tract is functional only when its blood supply, nerve supply, enzymes and hormones are integrated and unified by complex interrelationships.

PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH TO HOLISTIC CONSULTATION

One of the most difficult duties as a human being is to listen to the voices of those who suffer … listening is hard but fundamentally a moral act.24

The holistic consultation and treatment of the whole person includes emotional, mental, spiritual, physical and environmental factors, and it aims to promote wellbeing through the whole person rather than just the symptomatic relief of a disease. To best enhance this holistic consultative process a ‘patient-centred’ approach is used. This is where the emphasis is on patient autonomy; the patient and practitioner are in an equal relationship that values and respects the wants and needs of the patient.25 The role of the practitioner is to develop a therapeutic relationship of rapport, empathy and authenticity to serve the patient’s choices and engender the healing process.

An essential component of developing a therapeutic relationship with the patient is the ability to listen.26 Naturopaths must never forget that each patient is an individual with their own unique story of illness and treatment. The patient needs to be allowed to tell that story and in turn the naturopathic practitioner needs to listen with sensitive, authentic attention and empathy. This disciplined type of therapeutic listening bonds the patient and practitioner and enhances the effectiveness of treatment.27

A practitioner needs to be aware that a holistic consultation is not a routine event for the patient. It is dense with meaning and can represent a turning point for them.28 Fully listening to a patient’s concerns in a patient-centred holistic consultation helps the naturopath to explore and understand what is at stake and why it matters so much.29 With this knowledge it is then possible to provide appropriate and effective treatment. Establishing rapport, empathy and authenticity in a patient-centred holistic consultation also enhances the practitioner’s ongoing ability to assess recovery and to achieve the patient-centred aim of independent self-care.30

Phases of the holistic consultation

Adapting the Nelson-Jones31 model, there are five phases to the holistic patient centred consultation. These are to:

Understand

Understanding the problems involves a focused attempt to gather more specific details of the problems experienced by the patient. The naturopath’s facilitation skills will help the patient accurately focus on symptoms while also using the naturopath’s clinical skills in physical examination, body sign observations, reviewing medical reports and completing a systems history to gain and impart a holistic overview. The knowledge gained from this helps the patient to acknowledge areas of strength and weakness in their health and to develop new insights and perceptions that will help them to relate to their health issues holistically. It is also appropriate in this phase to seek referrals for further diagnosis where necessary from biomedical or allied health professionals.

STRUCTURE AND TECHNIQUE OF CASE TAKING

Basic case-taking skills take 1 or 2 years to develop and a diligent naturopath over the years will be constantly improving and refining techniques.32 It may be overwhelming in the first few cases for novice practitioners, especially if the case (or the patient!) is complex. At times a patient may be difficult, angry or demanding and a practitioner

Source: Adapted from Boon et al. 2006.33

FROM NOVICE TO EXPERIENCED NATUROPATH

Competent naturopaths: begin to develop their own independent strategies for patients.

needs to have insight and strategies for dealing with this (see ‘Further reading’ at the end of this chapter, which highlights useful texts discussing these issues).

Novice practitioners may wish to begin any case, no matter how chronic or complex, by starting with a good case history of one key ailment that bothers the patient. This is designated as the ‘presenting complaint’.34 For example if the patient has five health issues to discuss, negotiate with the patient what is most important to them to work on first.

The presenting complaint

Holistic review

As part of a holistic consultation it is essential to enquire into a broad range of factors. This is where the consultation moves beyond the presenting complaint.35 It encompasses a review of the patient’s:

This can be done in any order that seems most comfortable between practitioner and patient. A holistic assessment is made of the patient’s vitality and symptoms by exploring the physical, mental, social and spiritual factors that affect them. A simple model of holistic assessment is first to explore the factors affecting the patient’s constitutional strength, which are the physical and mental attributes they are born with. This includes genetics, temperament and the inherent strengths and weaknesses of different physiological systems. Secondly, factors that occur over time are considered. These include the family and culture that the patient grew up with and the socioeconomic status and environment that they live in. They also include the types of diseases or traumas the patient has had, the diets and lifestyle they have followed and the patterns of adaptive behaviour that they have adopted. Thirdly, a holistic assessment needs to consider important, dramatic events that have overwhelmed an otherwise healthy person, such as severe stress, trauma or toxicity. Fourthly, the factors that trigger disturbances to vitality such as stress, injury, infection, toxicity, allergens and drugs need to be considered. Finally, a holistic assessment of the factors that sustain ongoing health issues, such as psychological, social, economic, environmental and ecological factors, is made.36

Galland37 cautions that care must be taken in holistic assessments. Careful listening to the patient is required, as the range of possibilities is extensive. The assessment needs to be comprehensive as there can be multiple factors that reinforce each other and the practitioner needs to constantly reassess the patient who has complex symptoms to avoid misdiagnosis. The practitioner also needs to be flexible as the same symptom in two different people, for example joint pain, may have different triggers; conversely, the same trigger, for example hot weather, may induce headache in one person and asthma in another.

Past history

Mind/emotion/spirit

Body systems

SIGNPOSTS FOR RECOVERY

Patients always ask ‘When will I get better?’ Prognosis is the forecast of the course of a disease. With illnesses that are familiar, such as a head cold, it is relatively predictable how long it takes for symptoms to resolve with treatment. As a novice practitioner progresses through their career and experiences a wider range of patients, the ability to give an accurate prognosis of a variety of health problems improves. However, there are always instances when it is very difficult to predict how a patient’s illness will respond to treatment and over what period of time. In instances of difficulty with predicting how long a patient will take to recover it is better to approach the issue from another angle. That is, rather than trying to give the patient a definitive time frame of amelioration of the illness it is better to give estimations of what signposts or stages the patient is expected to experience and leave the issue of duration open-ended. This prevents the frustration a patient may experience when told they should be better by a certain date but they are not.

CASE TAKING—THE RETURN VISIT

What to do in the second session

Before the patient arrives the practitioner needs to re-familiarise themselves with the patient’s case. This can include the patient’s personal and social anecdotes of things that they were going to be doing during the week, such as family functions, outings with friends, work issues or relationship issues. To quickly re-establish rapport the practitioner can remind themselves of how the patient was feeling in the first session.

CASE TAKING—ADVANCED

Getting the details of chronic complex cases requires careful attention. As previously stated getting these details could take a number of sessions for novice practitioners. The written data obtained need to be accurate, comprehensive and easily recoverable. The practitioner should be able to quickly find any data on any question from any session because all the data are put into specific locations in the history form.

Complex cases: an example of how to summarise complex data

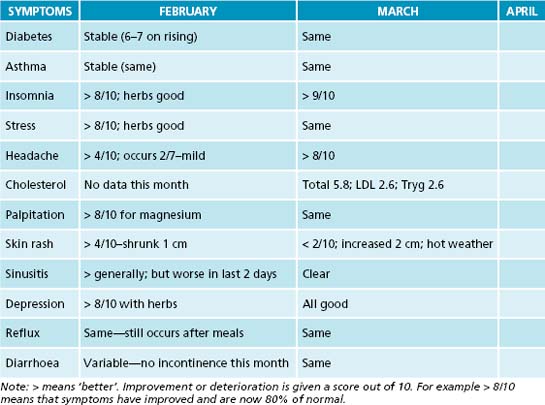

After taking a couple of sessions to get full details of his complete case history the practitioner’s subsequent sessions now involve tracking and reviewing his symptoms and response to treatment. This can be done on a simple spreadsheet by asking specific questions in each category and recording it in a summary table (such as Table 1.2). Every month the practitioner checks these symptoms and adds or subtracts other symptoms that come and go.

Active listening. Australian Family Physician, 2005. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/200512/200512robinson.pdf

Cava R. Dealing with difficult people. Sydney: Pan Macmillan; 2000.

Egan G. The skilled helper: a problem management approach to healing, 6th edn. Pacific Grove: Brooks Cole Publishing; 1998.

Geldard D., Geldard K. Basic personal counselling: a training manual for counsellors, 5th edn. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2005.

Interpersonal counselling in general practice. Australian Family Physician, 2004. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/200405/20040510judd.pdf

Ivey A.E., Ivey M.B. Intentional interviewing and counselling: facilitating client development in a multicultural society. Pacific Grove: Thomson Brooks Cole; 2003.

Murtagh J.E. General practice, 3rd edn. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill Australia; 2006. Chapter 4 Communication skills. Chapter 5 Counselling skills. Chapter 6 Difficult, demanding and trying patients

Navigating through the swampy lowlands. Dealing with the patient when the diagnosis is unclear. Australian Family Physician, 2006. Online. Available: http://www.racgp.org.au/afp/200612/20061205stone.pdf

Nelson-Jones R. Human relating skills, 3rd edn. Marrickville: Harcourt Brace; 1996.

Surviving the ‘heartsink’ experience. Family Practice, 1995. Online. Available: http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/12/2/176

1. Coulter I.D., Willis M. The rise and rise of complementary and alternative medicine: a sociological perspective. Med J Aust. 2004;180:587.

2. Pizzorno J.E., Snider P. Naturopathic medicine. In: Micozzi M., editor. Fundamentals of complementary and integrative medicine. 3rd edn. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:221-255.

3. Kaptchuck T.J. Vitalism. In: Micozzi M., editor. Fundamentals of complementary and integrative medicine. 3rd edn. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:53-63.

4. Bradley R. Philosophy of natural medicine. In: Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T., editors. Textbook of natural medicine. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:42-44.

5. Di Stefano V. Holism and complementary medicine: origin and principles. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2006. Chapter 4

6. Cody G. History of naturopathic medicine. In: Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T., editors. Textbook of natural medicine. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:41-49.

7. Schneirov M., Geczik J. Alternative health care and the challenges of institutionalization. Health. 2002;6(2):201-220.

8. Baer H.A., Coulter I.D. Introduction – taking stock of integrative medicine; broadening biomedicine or co-option of complementary and alternative medicine? Health Sociology Review. 2008;17(4):332.

9. Braun L., Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence based guide, 2nd edn. Marrickville: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2007. 71–73

10. Ernst E. The clinical researcher. Journal of Complementary Medicine. 2004;3(1):44-45.

11. Bradley R. Philosophy of natural medicine. In: Pizzorno J.E., Murray M.T., editors. Textbook of natural medicine. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:41.

12. Hoffman D., editor. The herbal handbook: a user’s guide to medical herbalism. Rochester: Healing Arts Press; 1988:18-19

13. Di Stefano V. Holism and complementary medicine: origin and principles. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2006. 107–108

14. Kirschner M., et al. Molecular vitalism. Cell. 2000;100(1):87.

15. Bechtel W., et al. Vitalism. In: Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge; 2000:919.

16. Turner R.N. The foundations of health. In: Naturopathic medicine. England: Thorsons Publishing Group; 1990:17-27.

17. Jacka J. A philosophy of healing. Melbourne: Inkata Press; 1997. 36–38

18. Pizzorno J.E., Snider P. Naturopathic medicine. In: Micozzi M., editor. Fundamentals of complementary and integrative medicine. 3rd edn. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:236-238.

19. Jensen B., editor. Iridology: the science and practice in the healing arts, Volume 2. Escondido: Bernard Jensen Publisher; 1982:181-183

20. Models for the study of whole systems. Bell I.R., Koithan M., editors. Integrative Cancer Therapies; 2006 5(4):295

21. Dunne R., Watkins J. Complementary medicine–some definitions. Journal of the Royal Society of Health. 1997;117(5):287-291.

22. Moore B., editor. The Australian Oxford Dictionary, 2nd edn. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2004:598.

23. Wentzel J. Holism. In: Van Huyssteen W., et al, editors. Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. 2nd edn. New York: Thomson Gale Macmillan Reference; 2003:412-414.

24. Frank A. The wounded story teller: body, illness and ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. 25

25. Emmanuel E., Emmanuel K. Four models of the physician–patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2225-2226.

26. Connelly J. Narrative possibilities: using mindfulness in clinical practice. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2005;48(1):84.

27. Charon R. The ethicality of narrative medicine. In: Hurwitz B., Greenhalgh T., Skultans V., editors. Narrative research in health and illness. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2004:30.

28. Mattingly C. Performance Narratives in the clinical world. In: Hurwitz B., Greenhalgh T., Skultans V., editors. Narrative research in health and illness. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2004:73.

29. Berlinger N. After harm: medical harm and the ethics of forgiveness. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. 3

30. Kumar P., Clarke M., editors. Kumar & Clark Clinical Medicine. Edinburgh, New York: WB Saunders; 2005:8.

31. Nelson-Jones R. Practical counselling and helping skills, 2nd edn. Marrickville: Holt Rhinehart Wilson/Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group (Australia); 1988. 92

32. Murtagh J.E. General practice, 3rd edn. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill Australia; 2006. chapters 4–5

33. Boon N.A., editor. Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine, 20th edn. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006:6.

34. Bates B. A guide to physical examination and history taking. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1995.

35. Seidel H. Mosby’s guide to physical examination. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. 9, 22

36. Galland L. Power healing: use the new integrated medicine to cure yourself. New York: Random House; 1997. 52–84

37. Galland L. Power healing: use the new integrated medicine to cure yourself. New York: Random House; 1997. 64