Chapter 108 Native American Healing

The very concept of Native American wilderness medicine may seem redundant. Until the industrial age, all Native American medicine was learned, developed, and practiced in the wilderness. One might be of the mindset that the wisdom of ancient subsistence cultures has little relevance to the modern world. However, from an indigenous perspective, modern Americans are no less subsistence based (and therefore entirely dependent on the earth’s resources) than were precontact (i.e., before 1492) Native Americans. As ecologist Gary Holtaus clearly explains, we are still a subsistence culture—although not a sustainable one.35 The Native American model of health, in which nature is the source of healing power, is as applicable today as at any time in the past.

Each of the thousands of precontact tribes of “Turtle Island”—a common indigenous name for North America—had its strategies and tools for health, adaptation, and survival. Many of these tools are still used among the approximately 700 Native Nations that remain today. The methods are as varied and rich as the North American landscape. The Yoeme of the Sonoran Desert recognize herbs that protect against heat and snakebite, whereas the Inupiaq in Alaska are more concerned with frostbite and mosquito stings. Different remedies are found in the desert, plains, tundra, and mountains and near lakes, rivers, and seas. Similarly, the requirements and seasons for vision seeking, pilgrimage, and ceremony vary by latitude and longitude. In the Northern Plains, it is rare to engage in a fasting and prayer vigil before the first spring thunder. Certain Pacific Northwest peoples may seek spiritual power in the winter, because the rainy season is a good time to commune with the spirit of water. With so much diversity, it is impossible in a single chapter to explore in depth the specifics of Native American wilderness medicine. These are better gleaned from many excellent ethnographies, herbal texts,* and biographies of traditional healers† as well as the few comprehensive surveys of Native healing ways.5,18,48,76 This chapter introduces widely shared principles as well as the ethos on which Native American medicine is based, illustrating the applications of this worldview with clinical examples from various tribes and geographic regions. America’s original holistic medicine can enhance the modern practice of integrative medicine.

Definitions

Native American

There is no single Native American or First Nations culture. There are more than 4.3 million indigenous Americans in the United States58 and another 1.3 million in Canada,67 which are divided into more than 1162 recognized Native governments: approximately 600 in Canada, 562 in the United States, and hundreds more in various stages of the recognition process.61 Approximately 225 Native languages are spoken in the United States, and another 50 in Canada.3,61 A far greater number of North American indigenous languages are extinct or are no longer spoken fluently. These languages are divided into 50 language families, many as different from each other as Romance (e.g., Italian) from Sino-Tibetan.

Old Hollywood movies and popular literature characterized as “New Age”80 promote a particular kind of generic Indian: in buckskins and feathered headdresses, speaking Tonto-like broken English, and frozen in popular imagination in western landscapes. Museum exhibits that I saw as a child did little to correct the impression that Native Americans were relics from the past rather than a people concerned about their future. Today’s Native Americans wear business suits rather than buckskins, prize higher education, and generally identify themselves as Christian (i.e., approximately 85% in the southeastern United States). They are patriots and volunteer in the armed forces in higher percentages than does any other ethnicity. They live in houses and apartments—not in tipis.

Indigenous Americans live in two worlds: the culture of their ancestors and that of the modern United States and Canada. Health care choices are influenced by this duality. Although Native Americans are more likely to seek an allopathic physician than a traditional tribal healer, there remains widespread respect for many traditional remedies, such as prayers, herbal medicines, counseling, and ceremonies. Sometimes ancient and modern healing methods are combined to create synergistic effects.25,28 Prescription medicines smudged in sage smoke and prepared with prayer are believed to be more effective than other methods of administration. Counseling complements the sweat lodge for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder.12 Among diabetes patients, nutrient ratios are managed with a traditional native diet by substituting indigenous grains such as amaranth and wild rice for high-glycemic starches such as potatoes and bread. Native healers have always practiced “holistic” or “integrative” medicine. These terms take on more meaning as Native Americans find creative ways to combine the old and the new.

Health

Like their Western counterparts, Native healers are concerned with relieving suffering, improving quality of life, and managing or curing disease. The World Health Organization’s definition of health is congruent with that of many Native American healers: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”83 Native healers add to this definition two more elements: spiritual and environmental. Health becomes a state of balance characterized by physical, mental, social, spiritual, and environmental well-being. Implicit in this definition is a philosophy summarized by the saying “All my relations (or relatives).” Whether recited in English or in a Native language (e.g., “Mitakuye Oyasin” in Lakota), this phrase means that health is a state of connectedness in which stones, plants, animals, and people are recognized as family. A type of affirmation that may close a prayer, it is sometimes compared with the word Amen, but it means much more than that. Amen, which is Hebrew for “so be it,” implies assent or approval, whereas Mitakuye Oyasin may be translated as “We are all children of the Great Spirit. May my words, prayer, song, and ceremonial actions be for the harmony and good of all.”

Traditional Healers

Many Native healing methods, such as herbal medicine, massage, and music, are similar to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies. Traditional North American Indian healers are often willing to share these methods with the public and with health care colleagues through lectures, courses, articles, books, and, more rarely, in collaborative research.51 However, it is important to understand that, when a technique is removed from its original context of culture, language, and geography, it may not be as effective. In addition, the Native American doctor is expected to “walk the talk” by being an example of Native values and actually believing in the reality of spiritual forces. It is not enough to imitate a method such as blending an herbal tea.

Native American healers may be specialists or have broad expertise. Among some tribes, there are separate terms for herbalists, bonesetters, midwives, diagnosticians, ceremonial experts, and people known for their gifts in massage, counseling, dreaming, or prayer. Some healers are recognized as holy people, whose direct contact with transcendent realms gives them the intuition, knowledge, and power to adapt or create methods that best fit the needs of their patients. These healers are popularly called medicine men, medicine women, or holy people. Fools Crow49 (Lakota) and Flora Jones5,41 (Wintu) are examples of well-respected 20th-century medicine people. None of the English language terms for indigenous healers are exact; they are often used indiscriminately in popular literature. A person described as a “medicine man” may be considered primarily an herbalist in his own tribe. An ethnographer may label a woman an “herbalist” who is in fact a medicine woman. In this chapter, I use the term “traditional healer” as a general category for all of the various types of indigenous North American healers. Traditional healers may be male or female and young or old, although I have not met a healer who is less than 35 years old—in fact, most are older than 50.

One becomes a traditional healer by any combination of an innate gift or talent; personal training, including ceremonial participation, vision seeking, fasting, or apprenticeship; and a ritual transfer of power from a previous healer. “Personal training”—although primarily experiential—may include learning from texts (e.g., healing chants and practices transcribed by the Cherokee in their own language)9 as well as from historic audio recordings and other media, including representations of healing practices in rock art or herbal remedies drawn on “pharmacopoeia sticks”53 (Figure 108-1). “Apprenticeship” involves learning from the example, demonstration, mentorship, and wisdom shared by a teacher.

Elder

The term elder occurs frequently in literature and discussions about Native American culture. Although this word may, at times, refer to a person’s age, it more commonly means a keeper of ancient traditional wisdom. According to the website of the Canadian Council of Elders, in the Algonquin Nation, “an Elder is defined as someone who possesses spiritual leadership which is given by one’s cultural and traditional knowledge. This knowledge is found in the teachings and responsibilities associated with sacred entities such as the Pipe, Wampum [sacred shell beads] belt, Drum and Medicine people. In addition to the spiritual recognition given by the Creator and the Spirit World, an elder is given the title and recognition as elder by other elders of his/her respective community and nation. Also one does not have to be a senior citizen to be an elder.”1 Various Indian Nations have their own definitions of the term elder, but the principles are similar. An elder passes along traditional values; he or she models, guides, and counsels people regarding how to live in a good way.

Etiology in a World of “All My Relations”

In an interconnected and interdependent universe, it is impossible to posit a distinct cause for any disease. An infectious agent requires a vulnerable host, and the degree of vulnerability is affected by many factors, including genetics, environment, emotions, cognitive habits, diet, exercise, timing, and previous health history. Native Americans accept this biomedical model but believe that illness and trauma may also have hidden precipitating causes. For example, was the climbing accident a result of lack of technical skill, simple carelessness, or perhaps not paying attention to warnings from the spirit world in the form of omens or dreams (Figure 108-2)? Ethical and spiritual transgressions (e.g., a breach of taboo), such as disrespectful behavior in or toward nature, may also cause misfortune.

Environmental

When using the term environmental, I mean, very simply, that our connection with nature and nature’s cycles is a major influence on health and well-being. Other things being equal, people who spend more time outdoors in a natural setting are physically and psychologically healthier. Children today are missing the freeform and unstructured play that is the basis of creativity. “Where do you like to play?” a third grader from San Diego was asked. “Inside,” he replied, “because that’s where the electric outlets are.”47 Children who play in nature are more resilient and better at reading and problem solving. Nature has measurable effects on the human organism. The earth’s magnetic field regulates biologic rhythms and gives humans, like homing pigeons, a sense of direction and orientation. Regular exposure to natural sunlight and evening darkness promotes optimal vitamin D and melatonin levels, the latter a requirement for restorative sleep and dreams.

Clean air and pure food and water allow us to be refreshed each day. This simple formula for health is becoming increasingly difficult to follow, as the United States Environmental Protection Agency warns of more than 3.8 billion pounds of toxic chemicals being released into the environment during a typical year.75 In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals measured 212 chemicals—including plastics, mercury, and arsenic—in blood and urine samples from 2400 U.S. citizens. Several industrial chemicals were found in nearly all participants, including polybrominated diphenyl ethers (fire retardants), bisphenol A (a component of epoxy resins), perfluorooctanoic acid (used in the manufacture of heat-resistant nonstick coatings in cookware), and the common gasoline additive methyl tert-butyl ether. Our health is also adversely affected by insecticides, herbicides, drugs, solvents, car and factory exhaust, electromagnetic fields, and ionizing radiation. There is clear evidence that toxic load is reaching a critical threshold after which further assaults result in increases in mortality and morbidity.14

Wilderness, say indigenous people, is healing. The degree of healing power or influence may also vary, with some places having more or less—hence the customs of pilgrimage to and vision seeking at sacred sites (Figure 108-3). To spend more time in healing places is to enhance one’s ability to resist and recover from disease. It is also the basis for recognizing healing herbs and connecting with their spirits, a necessity in Native herbal medicine.

Psychological/Psychosocial

The Cherokee traditional healer Rolling Thunder used to admonish, “Pollution begins in the mind” (Figure 108-4). Indeed, the reciprocal influence of mind and body, the core of today’s psychoneuroimmunology, is well accepted in Native American medicine. “No evil sorcerer can do as much harm to you as you can do to yourself with negative thinking,” the Samish traditional healer Johnny Moses once shared with me. Counseling, dream interpretation, and psychodrama (particularly the acting out of nighttime dreams) were common indigenous treatment modalities.18,78 A positive attitude goes a long way toward enhancing the efficacy of any therapy or making such therapy unnecessary. Traditional healers are often experts at inducing the placebo effect.

As I tried to demonstrate in “At the Canyon’s Edge: Depression in American Indian Culture,” psychological and psychogenic diseases are of urgent concern to today’s Native Americans.17 Duran and Duran have written insightfully about the prevalence of intergenerational post-traumatic stress disorder, resulting from the tragic history of Native peoples, their marginalization, the continuing challenges of racism, and the lasting effects of boarding school abuses and domestic violence.25 Some psychological problems are also the consequences of alcohol and drug abuse or birth defects, or associated with diseases such as diabetes and obesity. The breaking up of families and communities means that Native people now face problems on their own that would previously have been addressed by the group. Alienation and loneliness have replaced accountability and security. The programs most successful at treating psychological problems are integrative in nature, combining Western and indigenous therapies.28,69

Spiritual

The term spiritual refers to the causes of illness that concern or originate in the spirit, soul, or transcendent realms. Unlike with popular Christianity, in Native American philosophy, spirit and soul may be attributes of stones, plants, and animals, not just people. Emotions are also spirits. Traditional Cree healers in Saskatchewan say that the spirits of hatred or shame may cause disease, just as the spirits of love and forgiveness can heal. However, spirit is not opposed to flesh. Aspects of the soul may be linked with the breath of life (niya in Lakota) or with the spirit or ghost that exists after the death of the body (nagi in Lakota). Spirit is also an innate protecting force as well as a sacred power that may be gained by a person through sacrifice and contact with the divine (sicun in Lakota).23 My Cree relatives distinguish between the appearance of the soul as a “ghost” (tchi-pay) while it remains on Earth and the soul (at’-tshak) that journeys to the spirit world.26 The latter term, at’-tshak, is the root of the word for “star,” which is at’-tshakos. The stars are the spirits of those who have passed on, and the trail they walk is the Milky Way. We can see that not only are spirit and matter not separate, but that the spiritual realm interpenetrates the ordinary. People can contact this other reality through prayer, ceremony, and waking or sleeping dreams.

Contact with spirits may help prevent disease, but it can also cause disease. There is an ancient legend among the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes that the spirits of animals caused disease as retribution for disrespectful hunting practices that today would be called “trophy hunting.”54 Illness results when people insult or mistreat animals, invade or destroy their habitat, or fail to show respect to animals while hunting or eating them. In Crossing into Medicine Country, Choctaw author David Carson associates specific illnesses with various animals.13 If a person knows this connection, he or she may be able to relieve symptoms or cure disease by honoring the animal (e.g., with a feast among friends that is specifically intended to honor the animal) or by asking forgiveness from the offended animal spirit. As a sign of reconciliation, the animal may heal the illness directly or appear in a dream to offer advice.

Spirits may be capricious, mischievous, or malevolent. For this reason, elders advise not contacting the realm of spirits unless one is in need, emotionally mature, or prepared and aided by a traditional healer. Sorcerers, popularly called witches by some Native tribes (although they are not to be confused with Western pagan Wicca traditions), can inflict harm by sending disease-causing spirits to their victims. Although many, if not most, of these phenomena are probably examples of the nocebo effect, my personal opinion is that negative intent can have concrete effects even if the victim does not believe in or is unaware of the “curse.” Sorcerers may be hired by people to inflict harm and misfortune on other people, or they may be personally motivated to perform such criminal activities as a result of emotional imbalance (most commonly jealousy).24,77

There is also a traditional and widely held Native philosophy that negative actions eventually return to plague the perpetrator. Rolling Thunder taught that good deeds and bad deeds are both multiplied by seven to help or harm the person who performs them.11 Tuscarora traditional healer Ted Williams used to say that life is governed by natural and moral laws.81 To break these laws is the inner meaning of “breaking a taboo.” To strike a child, disrespect an elder, pollute the earth, or, in general, to act with greed, malice, or egotism is to break the Creator’s law. The result is illness in body, mind, or spirit.

Assessment and Diagnosis

Extrasensory phenomena are reported in association with traditional Native American diagnosis, reminding one of the out-of-body and clairvoyant skills of Edgar Cayce.68 I know traditional healers who, when told of a physical trauma, travel psychically to the place of the occurrence to see it for themselves. They may find, at the site of an accident, a lost soul that needs to be retrieved. Other healers have “sympathy pains” starting hours or days before they see an unexpected client for the first time. I once met an Ojibwe healer who specialized in diagnosing and treating from a distance. I experienced her work firsthand. In 1989, she and I met during a conference in Ontario. Years earlier septic arthritis had destroyed all of the cartilage in both of my hips. Noticing my disability, she offered to perform a healing on a specific day and time a few weeks later, after I returned to my home in Colorado. I did not remember the date I had scribbled in a small travel calendar. At the time, I was becoming increasingly skeptical because of the number of generally ineffective alternative healers who had tried to help me. I accepted my inability to climb stairs or to tie my shoelaces as an inconvenience with which I could live. However, one evening while sitting at my kitchen table, I felt a strange sensation, as though an electrically charged cloud surrounded me. I noticed that my hips, legs, and back had suddenly become comfortable. I bent forward and miraculously touched my toes. I then sat on the floor and crossed my legs, an impossible task both before and since. My range of motion was nearly normal. Of course, at this point, I remembered the meeting with the Ojibwe healer and, sure enough, this was the appointed evening. The change lasted for several hours. The next morning, when I woke up, I found that my previous level of disability had returned. For me, this healing remains a shining and encouraging example of the potential to heal and the power of indigenous medicine.

Treatment

In Native American healing, diagnosis and treatment are not rigidly divided and are often included in the same therapeutic session. This is true with ceremonial healing (e.g., the sweat lodge), with massage therapy, and especially with counseling. For example, ethnographers have noted the importance of dream interpretation and dream psychodrama among the Haudenosaunee.78 Tribal members would act out ominous dreams to create more favorable outcomes and thus avoid misfortune. When telling the dream (i.e., diagnosis), the resolution (i.e., treatment) becomes obvious. Similarly, during counseling, the traditional healer listens to the patient and offers meaningful advice or spiritual therapies. My adoptive father, Andrew Naytowhow (Cree), a traditional healer, counseled people in prisons; he sometimes offered advice or “doctored” them with prayer and pipe ceremonies (Figure 108-5). Often just talking about one’s feelings was all the healing needed. Dad would host “talking circles” among troubled youth. For a talking circle, after an opening prayer, each person speaks in turn, without interruption or commentary, sometimes followed by group discussion. I use counseling in my own traditional healing practice. After prayer and noncontact energy healing, one of my clients, a Native man in jail for assault broke down in tears and admitted to me the tragic circumstances in his life that had led to his actions. This was an important step in his return to “the Good Red Road,” the Native American path of a spiritual and ethical life.

The most common categories of Native therapeutics are: smudging (i.e., cleansing with the smoke of a sacred plant [Figure 108-6]); prayer and chant; music; counseling; vision seeking, dreaming, and fasting; energy therapies; ceremonies; and herbs. These methods and their purposes are outlined in Table 108-1, an early version of which appeared in Honoring the Medicine: The Essential Guide to Native American Healing.18 However, this is by no means an all-inclusive list.

| Method | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Smudging |

* The Apache violin or tsii’edo’a’tl (“wood that sings”) is an ancient instrument that is played during some social songs, ceremonial songs, and healing rituals. The body of the instrument is made of the century plant, which is related to agave and common in Arizona.

An additional category not discussed here is Indian Christian healing. For the many Native Americans who identify themselves as Christian, the term Native American healing means methods of healing that are acceptable to their pastors and to their churches, such as the Catholic laying on of hands, revival meetings, and charismatic prayer groups. Some churches, such as the Native American Church65 or the Indian Shaker Church in the Pacific Northwest,60 integrate Christian symbolism with Native American songs and healing practices. Mexican Americans of Native or mixed background also blend indigenous and Christian elements in curanderismo, common throughout Central and South America, as well as in Arizona, Texas, Southern California, and wherever there are large Hispanic populations.73 Although important culturally and socially, and reported effective for treatment of many illnesses, Indian Christian healing is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Contraindications

Unfortunately, there are no statistical data that address the level of adverse effects of Native American medicine. One of the very few reported cases is of a healthy 32-year-old Zuni woman who suffered a stroke from a left vertebral artery dissection after manipulation by a Native bonesetter. She was discharged from the hospital with warfarin anticoagulation therapy and improved quickly.59 A glaring example of the dangers of Native therapies that are attempted by improperly trained individuals was in the widely publicized tragedy that occurred during a sweat lodge ceremony in Sedona, Arizona, on October 9, 2009, leaving 3 persons dead and 21 hospitalized. A traditional sweat lodge is a small dome-like sauna covered by “breathable” blankets and hides, with room for 12 to 20 people. Participants have a chance to exit the lodge as needed or at prescribed times. In the Sedona sweat lodge, a monstrous 415 foot2 dome covered in plastic, approximately 60 people were trapped for 2 hours. Their leader, a non-Native motivational speaker, advised that they could survive their ordeal, but he was wrong.16 There have been other less dramatic examples of adverse effects, and it is likely that many are not reported.

Clinical Example: Back Pain

Herbal medicine is a common remedy for back pain. Salicin, the well-known analgesic in aspirin, was first listed in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia in 1882. It is found in all species of willow (Salix), and was a traditional pain remedy among many tribes. For example, the Blackfeet steeped willow twigs in boiling water for fever and pain. Alaskan Inupiat chewed on green willow bark specifically for back pain.29 Alabama Indians applied a poultice made of the pulp of the saw palmetto roots to a broken or injured back.76 The Innu of Quebec and Baffin Island drank wintergreen root tea for back troubles of any kind. The Catawba, from North and South Carolina, crushed fresh horsemint leaves and steeped them in water. The tea was drunk every day to relieve back pain. They also used an arnica root wash for sprains and bruises.15 The Kashaya Pomo of North Central California used a pepperwood leaf poultice for nerve pain. They also made a poultice from the root of cow parsnip (Heracleum lanatum), baking the root, mashing it, and placing it on the painful area under a rag, leaving it overnight.31 Alaskan Aleut used a compress of heated cow parsnip leaves as a compress for muscle pain.29 San Carlos Apache from Arizona made a dry poultice of greasewood (Covillea tridentata), heating the top of the plant and applying it directly to the painful area.76 The creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), confusingly sometimes also called “greasewood,” is used by many Arizona and Southern California tribes as a cure-all. Heated branches, twigs, or leaves are placed on the body to relieve pain. It is also common to treat pain with creosote steam or smoke.22 Passamoquody herbalist Fredda Paul of Maine admires the healing properties of horsetail (Equisetum arvense, Equisetum hyemale, and Equisetum sylvaticum), also popularly called “shave grass.” It is taken internally as a tea for aching or injured joints and ligaments and to help mend broken bones. Horsetail is rich in silica and may help build collagen.42 Like other plants, it must be administered with care, because the silica may aggravate hemorrhoids, and the raw shoots contain toxic thiaminase. It is also inadvisable for persons with cardiovascular disease.

Calamus, a member of the sweet flag (Acoraceae) family, is an immensely popular herb among Native Americans. It commonly grows in swamps and near water in boreal forests and has a broad range of applications. The Cree of Montana, Alberta, and Saskatchewan call it wacaskwatapih (“muskrat root” or, more commonly, “rat root”), and believe that muskrat meat is especially nourishing and spiritually potent because muskrats eat this healing root. Cree herbalists recommend chewing on the root to overcome fatigue during long hikes or strenuous activities. It is also applied for the treatment of back pain. The fresh, or dried and ground, rhizome is chewed and used as a poultice for painful joints. The root may also be chopped and put in boiling water to make tea, which is then mixed with flour and applied as a hot paste over arthritic joints. The painful area is then wrapped with warm towels and left overnight.50 The Muskogee Creek, who originally inhabited the region from Georgia to Alabama, use calamus tea in a similar manner, applying it within a hot compress to reduce inflammation and soothe sore joints and back pain. The Creek also use yarrow, another ubiquitous and popular plant, for painful or deep bruises from falls. The smashed leaves or a lukewarm tea made from the leaves are placed in a compress over the bruise. In a modern application, the leaves and flowers may also be soaked in isopropyl alcohol for 7 days to make an antiinflammatory liniment for joint pain and poor circulation.21

Cherokee and Hitchiti herbalist Tis Mal Crow recommends a liniment made from Solomon’s seal root (Polygonatum biflorum) for back pain, sprains, misaligned bones, and ruptured discs.21 The Tlingit and other Alaskan tribes make ointment or massage oil with skunk cabbage or devil’s club for joint and muscle pain.34 Devil’s club (Oplopanax horridus) (Figure 108-7), sometimes called “Indian ginseng,” is greatly admired among Northwest and Alaska Native peoples for its broad healing and spiritual qualities, and is somewhat of a panacea.45

Massage is a universal remedy for pain. Native healing specialists called “bonesetters” are common among many tribes, from the Yurok of California to the Yoeme of Arizona. In addition to setting broken bones, many of them also practice massage or prescribe herbs that teach the bones how to mend. Traditional healers commonly practice laying on of hands, placing the hands on or near painful areas. In Washington State, practitioners of the Si.Si.Wiss “sacred breath” healing tradition may work on a patient with a combination of smudging (generally with cedar smoke), song, dance, prayer, candlelight, and healing gestures of the hands.18,64 I have facilitated several Si.Si.Wiss healing ceremonies for patients with back pain. In one case, a 40-year-old white airline pilot joined a 2-hour healing ceremony without telling anyone about his diagnosis or symptoms. It was his first experience in a Native ceremony. A few years later, I met him by chance in a café, and he recounted an extraordinary story. He had been in a car accident 6 years earlier that had resulted in unremitting pain from three herniated discs: the third cervical and fourth and fifth lumbar discs. The pain was significantly diminished the day after the ceremony; within one week, it was completely gone, and had never returned. A 60-year-old Comanche woman who had suffered from years of discogenic back pain asked me to “doctor” her. I smudged her with a mixture of artemisia and sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata), waving the smoke over her body with a turkey feather fan. I then prayed to the Great Spirit for health and help while placing my palms directly on the painful area. I rested my palms there for about 10 minutes. The intervention closed with more prayers. Her pain was gone the next day and never returned.

Like modern massage therapists, Native healers used various oils to ease kneading and manipulation and to make the body more pliable. Oils were generally derived from animal fat, commonly bear, bobcat, and raccoon.76 The spirits of these animals were believed to contribute to the effectiveness of the massage. The power of massage could also be augmented by fanning the body with switches of cedar or other plants or by applying massage in a ceremonial or sanctified space such as a sweat lodge. Some traditional healers are especially efficacious because of the way they prepare themselves for healing. Cherokee healers warm their hands over an outdoor fire and then rub the painful area with circular motions of the palms.76 Some healers imagine that they are becoming or communing with a dream helper, such as a badger, a thunderbird (symbol of thunder, lightning, and life energy), or bear. In the minds of both healer and patient it is, perhaps, the bear who “doctors” the patient and whose “paws” massage the painful area. The bear is one of the most common representations of healing among North American Indians. There is a natural association between the bear and sleeping and dreaming and between the bear and herbal medicine. Other than human beings, bears are the only North American mammals with a rotating forearm, giving them the manual dexterity to dig healing roots (Figure 108-8). However, the spirituality and power of the healer are considered more important than the technique used.

Back pain and spasms are often relieved by heat. This fact did not escape traditional healers, who recommended hot compresses, the heat of the sweat lodge, and bathing in hot springs. Rolling Thunder sometimes advised his patients to lie down on a “bed” of warm sand on the beach and consciously, meditatively allow the warmth to heal the back. Like the ancient Chinese, Native American healers have for millennia applied warmth to muscles, joints, or specific therapeutic points to relieve pain. In Chinese medicine, a small ball of moxa (mugwort) is burned at the end of the acupuncture needle to transmit heat and to increase the therapeutic effect. Similarly, Cree Indians take a pinch of tinder fungus, found under the bark of birch trees, roll it into a matchstick shape, and burn it on the skin to treat arthritis.50 Omaha Indians used stems of the shoestring plant in a similar fashion.30 The Blackfoot sometimes inserted prickly pear or rose thorns into specific areas on the skin to relieve pain. These thorns may also have been heated by burning them. Historian Robert Beverley, Jr (1673-1722), reported that the Indians of Virginia fixed “a pain in any particular Joynt or Limb” by making a cone from soft or rotting wood in the knots in hickory or oak trees and burning it down to the skin over painful areas.8 Most Native American languages have a word for life force or breath of life (ni in Lakota), similar to the Chinese concept of qi. It is logical to infer from this that indigenous acupuncture was not merely a counterirritant but rather an example of energy medicine.37 However, counterirritants were not unknown. Many tribes, such as the Chehalis and Quileute of Washington, applied switches of stinging nettles to painful backs.33

Adolf Hungry Wolf recounts a fascinating example of Blackfoot Indian “moxabustion” in his 1975 edition of Teachings of Nature.82 A Blackfoot elder told Hungry Wolf, “…a horse fell on me once. My knee really swelled up. My father told my mother to go get some thorns from a Rose bush, and he told her to bake them… He checked over my injured leg and he took one of the hot thorns and he pushed it in.”82 His father inserted the thorns directly into the swollen area and then burned them down to the skin. He repeated the treatment later that same day. “This time the swelling went right down and I was able to walk. I guess that was a form of what they call, today, Acupuncture.”82

The Challenges of Research

Native American medicine is not found among the categories of CAM on the website of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.55 In various presentations and documents, I advised officials from the National Institutes of Health that Native American medicine is too closely connected with political, economic, religious, and social issues to be considered a CAM method.19,63 I was also concerned that the benefits of research and control over its applications remain in the hands of the sovereign Native Nations to whom the healing methods belong. It would be a travesty for non-Native licensing or accreditation boards to create standards for or assume control over Native spirituality and culture.

The scientific analysis of Native American healing methods removed from their cultural context poses special challenges for creating standard conditions or replicable experiments. From an indigenous viewpoint, analyzing the chemistry and biologically active agents in plant medicines has limited value. To be effective, plants must be gathered by hand and not bought in a store or pharmacy. Native herbalists also pay attention to the time of day or season to dig roots or pick leaves and are careful to leave enough of a species for regrowth. The way an herbalist handles or prepares an herb (e.g., cutting, drying, mashing, crushing) may increase or decrease a plant’s potency. For example, Mohegan herbalist Gladys Tantaquidgeon states that many herbalists prefer to dry their medicines in the sun and crush them with a stone or wood mortar “to avoid contamination by metal.”70

Interventions vary according to the needs of the patient and the intuition of the healer. The location is also considered an influence on treatment outcome. In other words, an herbal medicine or massage received in a hogan, kiva, sweat lodge, or beautiful place in nature has a different effect than the same therapy applied in an office or hospital or studied in the laboratory. Songs and prayers may not be repeated, even when treating the same disease, and there is also the possibility that the powers they invoke are impossible to measure. A traditional healer would not wish to rule out the placebo effect, if it was a possibility. The presence of the healer, the quality of relationship between healer and patient, and the faith of the patient are powerful influences on treatment outcome. Levin defines faith as “a confluence of belief, trust, and obedience in relation to God or the divine.”46

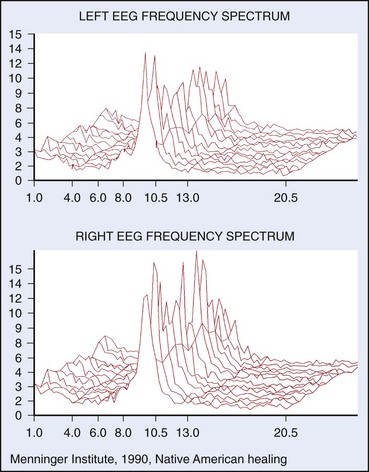

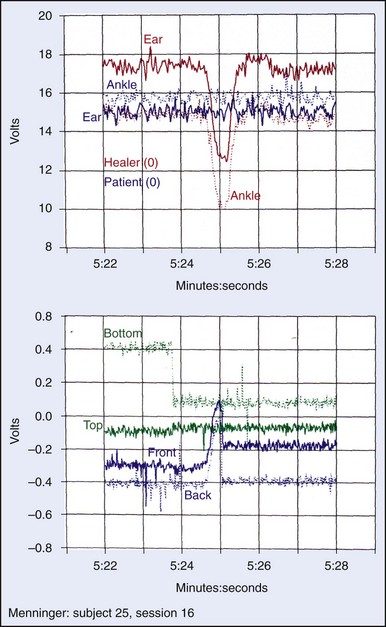

This does not mean that scientific research in this field is of no value. On the contrary, research can provide an alternative model for interpreting and appreciating healing phenomena.51 Some prominent websites, including those of the American Cancer Society2 and the University of California, San Diego Medical Center claim that the “[f]ormal research of the healing ceremonies and traditions of Native Americans is almost nonexistent even though claims have been made regarding cures of a variety of ailments, including cancer.”74 However, this is not quite true. We have little data about Native American healing that has been conducted by traditional healers, especially in the context of their own communities or with members of their own tribes. At the same time, the major modalities applied by Native healers have been extensively researched and documented, including herbal medicine, music, touch, massage, and prayer. For example, in “Physical Fields and States of Consciousness,” a 12-year research project conducted by the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas, scientists measured extraordinary surges in body potential, bioelectric fields, and brain-wave amplitude when various well-known healers, including some practitioners of Native American Medicine, attempted to emit healing energy, with or without an actual patient being present (Figures 108-9 and 108-10). At the same time, 600 control experiments with “regular” untrained subjects produced no such phenomena.32,71,72 Given the documented effects of drumming on auditory driving and intuition, I believe that even stronger effects would have been evident if Native healers had used drums or other percussive instruments during these experiments.38,56,57,62,79 However, this would have created movement artifacts, making data interpretation almost impossible. It is also likely that the sensory saturation common during Native rituals—olfactory (sage and cedar smoke), auditory (drumming), kinesthetic (dancing), and visual (masks and regalia)—causes synergistic neurophysiologic effects (e.g., the blocking of pain signals).

FIGURE 108-10 Anomalous changes in body potential, Menninger Clinic, 1990. Same subject and experimental session as in Figure 108-9. Upper graph shows the healer’s baseline ear electrode reading of approximately 17 v., dropping to approximately 13 v. before returning to baseline, and ankle electrode at 15 v. dropping to 10 v. All of this occurred at the moment the healer attempted to “send healing energy” to a subject in another room. No movement was permitted, and video cameras ruled out movement artifacts. The bottom graph displays voltage readings on four copper panels: bottom subflooring, top ceiling, front, and back. A significant spike in the front and back panels occurred in synchrony with the body potential surges.

Daniel Benor has collected and analyzed hundreds of CAM and spiritual healing abstracts previously published in peer-reviewed journals.7 Many U.S. hospitals, particularly those serving Native patients or close to reservations, provide integrative health services that allow patients to be treated by traditional healers, often in special Indian treatment rooms reserved for that purpose. I have visited these facilities in New Mexico, Wyoming, and Washington State. An administrator at one of these facilities told me that non-Indian physicians joined traditional healers in weekly sweat lodge ceremonies, after which they discussed collaborative treatment strategies. There are also numerous yearly conferences hosted by universities, clinics, and the Indian Health Service that focus on the dialogue between indigenous and Western medicine and the potential benefits of both research and clinical applications.

Finally, returning to a theme from the beginning of this chapter, spending time in nature, whether camping, hiking, or on pilgrimage, has measurable effects on health. Louv cites evidence for “nature-deficit disorder,” linked with decreased creativity as well as cognitive and emotional difficulties in both adults and children.47 Becker explains the mechanism by which the earth’s electromagnetic field influences healing and may program our biologic clocks and rhythms.6 Others have shown how rhythmic movement (e.g., healing and ceremonial dances) further encourages homeostasis. According to James R. Evans, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of South Carolina (Columbia), “Some [researchers] perceive the human body as a collection of oscillating subsystems more or less in harmony with each other; and the greater the harmony among the systems the less the ‘dis-ease,’ while the greater the dissonance the more severe the ‘dis-ease.’ According to some such views, internal order can be increased and hence the quality of the human ‘body symphony’ enhanced by exposure to ordered stimuli such as certain music, poetry and rhythms of nature and/or by participation in rhythmic movement activities as diverse as dancing, jogging, and certain martial arts. One might guess that dancing to music under the stars on a beach would be highly conducive to reestablishment of internal order!”27 It is likely that positive health-enhancing entrainment may also occur between the healer and healee.71,72 Through a process similar to what electrical engineers call “induction coupling,” the information-carrying signals in one neural network produce similar signals in an adjacent biologic system. Of course, the opposite is also possible: an ill-prepared healer may resonate with the patient’s disease or transmit his or her own disharmony.

In addition, it is important to consider that Native wilderness medicine today is different from that of the past. Modern lifestyles and habits create special challenges for a traditional healer. Many people, including Native Americans, are uncomfortable in the wilderness. Although people try to control it, when we are in nature, we are faced with a reality that is beyond our control and unpredictable. A fall or fracture in the forest may be doubly frightening: first because it happens in nature and second because one is likely to be far from the security of a hospital. Alienation, helplessness, and fear exacerbate pain, impede healing, and may lead to panic. Thus, the very first task of the traditional healer is to communicate to the patient by word, deed, or symbol that the patient is safe and at home. The healer encourages the patient to accept and relax into a reality that, from a deeper perspective, has always been present. “The Tao [harmony of nature] is that which cannot be deviated from,” an ancient Chinese text reminds us; “[i]f you could get away from it, it wouldn’t be the Tao.”20

1 Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. Kumik—Council of Elders. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ach/ev/kmk/index-eng.asp.

2 American Cancer Society. Native American healing. http://www.cancer.org/docroot/ETO/content/ETO_5_3X_Native_American_Healing.asp?sitearea=ETO.

3 Assembly of First Nations. State of First Nations languages in Canada. http://www.afn.ca/article.asp?id=831.

4 Bear H, Larkin M. The wind is my mother: The life and teachings of a Native American shaman. New York: Clarkson Potter; 1996.

5 Beck PV, Walters AL. The sacred: Ways of knowledge, sources of life. Tsaile (Navajo Nation), Ariz: Navajo Community College Press; 1977.

6 Becker RO, Seldon G. The body electric. New York: William Morrow and Company; 1985.

7 Benor D. Spiritual healing: Scientific validation of a healing revolution, professional supplement. Southfield, Mich: Vision Publications; 2002.

8 Beverley R. The history and present state of Virginia. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 1947.

9 Black Elk WH, Lyon WS. Black Elk: The sacred ways of a Lakota. San Francisco: Harper & Row; 1990.

10 Boyd D. Mad Bear: Spirit, healing, and the sacred in the life of a Native American medicine man. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1994.

11 Boyd D. Rolling thunder. New York: Dell Publishing; 1974.

12 Bruchac J. The Native American sweat lodge: History and legends. Freedom, Calif: The Crossing Press; 1993.

13 Carson D. Crossing into medicine country: A journey in Native American healing. Tulsa, Okla: Council Oak Books; 2007.

14 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/.

15 Cherokee Cultural Society of Houston. Native American herbal remedies. http://www.powersource.com/cherokee/herbal.html.

16 CNN.com. Sweat lodge deaths investigated as homicides. http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/10/15/arizona.sweat.lodge/index.html.

17 Cohen K. At the canyon’s edge: Depression in American Indian culture. Explore. 2008;2:127.

18 Cohen K. Honoring the medicine: The essential guide to Native American healing. New York: Ballantine Books; 2003.

19 Cohen K: Should Native American medicine be considered a CAM modality? Fax sent to the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine, October 3, 2001.

20 Confucius: The doctrine of the mean (Zhong yong). Translation by Kenneth Cohen. Unpublished, 2009.

21 Crow TM. Native plants, native healing, traditional Muskogee way. Summertown, Tenn: Book Publishing Company; 2001.

22 Curtin LSM. By the prophet of the Earth: Ethnobotany of the Pima. Tucson, Ariz: University of Arizona Press; 1949.

23 DeMallie RJ. Sioux Indian religion: Tradition and innovation. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press; 1989.

24 Dossey L. Be careful what you pray for…you just might get it. San Francisco: Harper; 1997.

25 Duran E, Duran B. Native American postcolonial psychology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995.

26 Dusenberry V. The Montana Cree: A study in religious persistence. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press; 1962.

27 Evans J, Clynes M, editors. Rhythm in psychological, linguistic and musical processes. Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas, 1986.

28 Four Worlds International Institute. Home page. http://www.fwii.net.

29 Garibaldi A. Medicinal flora of the Alaska natives. Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Natural Heritage Program; 1999.

30 Gilmore MR. Uses of plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press; 1977.

31 Goodrich J, Lawson C, Lawson VP. Kashaya Pomo plants. Los Angeles: University of California American Indian Studies Center; 1980.

32 Green E, Parks P, Guyer P, et al. Anomalous electrostatic phenomena in exceptional subjects. Subtle Energies. 1991;3:69.

33 Gunther E. Ethnobotany of Western Washington, the knowledge and use of indigenous plants by Native Americans. Seattle, Wash: University of Washington Press; 1973.

34 Gut’ Shu wu Inc. Traditional Tlinget medicine. http://gutshuwu.com/services.html.

35 Holtaus G. Learning native wisdom: What traditional cultures teach us about subsistence, sustainability, and spirituality. Lexington-Fayette, Ky: University Press of Kentucky; 2008.

36 Horse Capture G, editor. The seven visions of Bull Lodge. Ann Arbor, Mich: Bear Claw Press, 1980.

37 International Society for the Study of Subtle Energies and Energy Medicine. Home page. http://www.issseem.org.

38 Jilek WG. Indian healing: Shamanic ceremonialism in the Pacific Northwest today. Surrey, British Columbia, Canada: Hancock House Publishing; 1981.

39 Jones DE. Sanapia: Comanche medicine woman. Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland Press; 1972.

40 Kindscher K. Medicinal wild plants of the prairie: An ethnobotanical guide. Lawrence, Kan: University Press of Kansas; 1992.

41 Knudtson PM. The Wintun Indians of California and their neighbors. Happy Camp, Calif: Naturegraph Publishers; 1977.

42 Kuwesi-Medicine News. Passamaquoddy traditional medicine. http://www.kuwesimedicine.info/gathering.html.

43 Lake Medicine Grizzlybear. Native healer: Initiation into an ancient art. Wheaton, Ill: Quest Books; 1991.

44 Lame Deer J, Erdoes R. Lame Deer, seeker of visions. (Fire). Washington Square Press, New York, 1972..

45 Lantz TC, Swerhun K, Turner NJ. Devil’s club, an ethnobotanical review. Herbalgram. 2004;62:33.

46 Levin J. How faith heals: A theoretical model. Explore. 2009;2:77.

47 Louv R. Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books; 2008.

48 Lyon WS. Encyclopedia of Native American healing. New York: WW Norton; 1996.

49 Mails T. Fools Crow. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company; 1979.

50 Marles LJ, Clavelle C, Monteleone L, et al. Aboriginal plant use in Canada’s Northwest Boreal Forest. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: University of British Columbia Press; 2000.

51 Mehl-Madrona LE. Traditional (Native American) Indian medicine treatment of chronic illness: Development of an integrated program with conventional American medicine and evaluation of effectiveness. http://www.healing-arts.org/mehl-madrona/mmtraditionalpaper.htm.

52 Moerman D. Native American ethnobotany. Portland, Ore: Timber Press; 1998.

53 Moerman D. Native American herbal prescription sticks, indigenous 19th century pharmacopeias. Herbalgram. 2008;77:48.

54 Mooney J: Sacred formulas of the Cherokees. Bureau of American Ethnology, 7th Annual Report 1885-1886, Washington, DC, 1891.

55 National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. What is complementary and alternative medicine? http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/.

56 Neher A. A physiological explanation of unusual behavior in ceremonies involving drums. Hum Biol. 1962;34:151.

57 Neher A. Auditory driving observed with scale electrodes in normal subjects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1961;13:449.

58 Ogunwole SU. We the people: American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Census 2000 special reports. http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/censr-28.pdf.

59 Quintana JG, Drew EC, Richtsmeler TE, et al. Vertebral artery dissection and stroke following neck manipulation by Native American healer. Neurology. 2002;9:1434.

60 Ruby RH, Brown JA. Dreamer prophets of the Columbia Plateau: Smohala and Skolaskin. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press; 1989.

61 Russell G. Native American FAQs handbook. Phoenix, Ariz: Russell Publications; 2000.

62 Sargant W. Battle for the mind. London: Pan Books; 1959.

63 Shenandoah Healing Exploration Meeting. Rappahanock, Va, November, 1993.

64 SiSiWiss.org. Si.Si.Wiss resources on the Internet. http://www.sisiwiss.org/.

65 Smith H, Snake R, editors. One nation under God: The triumph of the Native American church. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers, 1996.

66 Snell AH. A taste of heritage: Crow Indian recipes & herbal medicines. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press; 2006.

67 Statistics Canada. Aboriginal peoples of Canada: A demographic profile. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/abor/canada.cfm.

68 Sugrue T. There is a river, the story of Edgar Cayce. Virginia Beach, Va: A.R.E. Press; 1973.

69 Swinomish Tribal Mental Health Project. A gathering of wisdoms, tribal mental health: A cultural perspective, ed 2. LaConner, Wash: Swinomish Tribal Community; 2002.

70 Tantaquidgeon G. Folk medicine of the Delaware and related Algonkian Indians. Harrisburg, Penn: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; 1977.

71 Tiller WA. Science and human transformation: Subtle energies, intentionality and consciousness. Walnut Creek, Calif: Pavior Publishing; 1997.

72 Tiller W, Green E, Parks P, et al. Towards explaining anomalously large body voltage surges on exceptional subjects. Journal of Scientific Exploration. 1995;3:331.

73 Trotter RTII, Chavira JA. Curanderismo: Mexican American folk healing. Athens, Ga: University of Georgia Press; 1981.

74 University of California, San Diego Moores Cancer Center. Complementary and alternative therapies for cancer patients. http://cancer.ucsd.edu/Outreach/PublicEducation/CAMs/nativeamerican.asp.

75 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) program: 2008 TRI national analysis. http://www.epa.gov/tri/tridata/tri08/national_analysis/index.htm.

76 Vogel VJ. American Indian medicine. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press; 1970.

77 Walker DEJr, editor. Witchcraft and sorcery of the American native peoples. Moscow, Idaho: University of Idaho Press, 1989.

78 Wallace AFC. Dreams and the wishes of the soul: A type of psychoanalytic theory among the seventeenth century Iroquois. Am Anthropol. 1958;60:234.

79 Walter VJ, Walter WG. The central effects of rhythmic sensory stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1949;1:57.

80 Wilber K. Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Boston: Shambala; 1995.

81 Williams T. Big medicine from six nations. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press; 2007.

82 Wolf AH. Teachings of nature: The Good Medicine Series No. 14. Invermere, British Columbia, Canada: Good Medicine Books; 1975.

83 World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. http://www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en/index.html.