3 NASHA™ family

Summary and Key Features

• NASHA™ are a safe, reliable class of dermal fillers that have low potential for allergic response

• NASHA™ fillers are non-permanent and thus ideal to use for treatment-naïve patients and for beginning injectors as they can be easily dissolved with hyaluronidase

• The type of injection technique selected (serial puncture, linear, fanning or cross-hatching) should be based on anatomical site

• Common areas for injection include the nasolabial folds, followed by the melolabial folds, jowls, and lips. Injection into the glabella is contraindicated owing to the risk of necrosis unless it is used with a tiny needle and injected superficially pulling back on the plunger before injection

• Depth of the fold or amount of volume replacement required are the key components to consider prior to product brand selection

• NASHA™ fillers can be layered on top of each other or on top of other semipermanent fillers

• Hyaluronic acid fillers can last from 3 to 6 months depending on location and amount of product previously injected; they last for longer in areas of low mobility and shorter in areas of greater movement

• Postoperative sequelae are usually edema and bruising lasting only a few days

Basic science

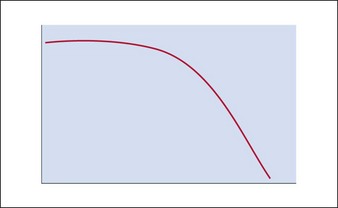

The hyaluronic acid molecule is stabilized with cross-linked hydroxyl groups. It is this cross-linking that confers longevity to the product in the skin and the degree of cross-linking one of the distinguishing features of NASHA™ products. Because of this structural matrix, the degradation curve of implanted HA is not linear. Rather, the product retains its effect until the structural complex around the HA molecule is broken down. Once the unbound HA is exposed, efficacy is then lost (Fig. 3.1). As a result, patients will often suddenly notice a change in their appearance rather than experience a gradual loss over time. In addition, patients sometimes feel they look worse after HA injection than they did prior to it; however, this is more of a function of selective memory. This is why taking pre-injection photographs is so important. As with natural hyaluronan, HA fillers can be instantly dissolved with the enzyme, hyaluronidase.

Choosing the right NASHA™

The main difference between commercially available NASHA™ products on the current US market is the viscosity of the product. The higher the concentration of HA, the stiffer is the product and the longer it lasts in tissue (Table 3.1). The larger the particle and the greater the concentration of the filler, the greater the lift you get. It should be noted, however, that not all of the HA in a given filler is cross-linked. Some is free, fragmented or only lightly cross-linked so that the gel can actually flow out of the syringe with ease. As discussed above, the cross-linking is what confers longevity to the product and this does vary between brands. In Restylane® and Juvéderm®, 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether is the cross-linking agent, which forms ether linkages in the HA chain. This same type of ether linkage is formed by diglycidyl sulfone found in Prevelle® Silk. In addition to cross-linking, it is worth mentioning that not all HA products are packaged in the fully hydrated state. As mentioned earlier, NASHA™ fillers create volume via hydration and, for this reason, patients will often look better or more filled 24 hours after treatment with products like Restylane® and Juvéderm, which are not completely saturated in the syringe. With that in mind, it is prudent not to overcorrect when using NASHA™ products.

Table 3.1 Hyaluronic acid (HA) concentration of commercially available NASHA™ products

| Trade name | HA concentration | Particle size* |

|---|---|---|

| Restylane® | 20 mg/mL | ~260 µm |

| Perlane® | 20 mg/mL | ~1000 µm |

| Juvéderm® | 24 mg/mL | 50–500 µm (very cohesive) |

| Juvéderm® Ultra Plus | 24 mg/mL | Homogeneous gel |

| Prevelle® Silk | 5.5 mg/mL | ~250 µm |

| Hydrelle® | 28 mg/mL | Not available |

| Hylaform® Plus | 5.5 mg/mL | ~700 µm |

* Even very cohesive products are particulate. The particle sizes of commercially available NASHA™ fillers are shown. In comparison, the particulate sizes of non-NASHA™ products are as follows: Radiesse® (25–45 µm), Artefill® (over 30–50 µm), Sculptra® (40–60 µm), Dermalive® (20–120 µm).

Patient evaluation

Prior to injection with any dermal filler, a careful patient history should be obtained. Pertinent items to note in this history include a history of herpes simplex virus, pregnancy or breastfeeding, history of keloid formation, presence of any autoimmune disease, and allergy to lidocaine as most of the fillers now come pre-mixed with lidocaine (Box 3.1). A medication history should include use of multivitamins, fish oil, vitamin E, blood thinners, aspirin, ibuprofen, and Gingko biloba, as all of these can predispose the patient to bruising. Unless medically necessary, the patient should be advised to discontinue these medications 14 days prior to treatment. In addition, alcohol use within 48 hours of injection can cause an increase in bruising tendency.

Treatment techniques

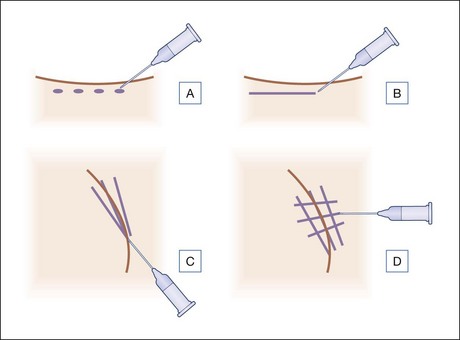

Several injection techniques exist for the addition of HA fillers to the face and depend mainly on the area of the face that is to be augmented. The four main techniques are illustrated in Figure 3.2. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages and all are based upon a transcutaneous approach.

Serial puncture

In this method (Fig. 3.2A), the bevel of the needle is pointed up and the product is dispensed in a droplet-like fashion along the fold that is to be lifted. Depending on the size of the aliquot, the physician may have to massage the area to prevent nodule formation. A disadvantage of this technique is that the patient will experience multiple needle sticks. Examples of areas to use this method include: depot in the infraorbital area with massage into the medial canthal region, acne scarring, and droplet into the lip tubercles (Table 3.2). Serial puncture is common for superficial dermal injections.

| Area | Technique |

|---|---|

| Nasolabial folds | Serial puncture, threading, fanning or cross-hatching; sharp needle or blunt-tipped cannula can be used |

| Melolabial folds | Fanning or cross-hatching; sharp needle or blunt-tipped cannula can be used |

| Jowls | Serial puncture (depot) or linear threading |

| Cheeks | Fanning or cross-hatching; blunt-tipped cannula can be used |

| Lips – vermilion border | Linear threading |

| Lips – tubercles | Serial puncture |

Linear threading

The physician points the bevel of the needle up and through one insertion point that is usually at the inferior pole of the fold, the needle is advanced forward, and the product is dispensed in a retrograde fashion as if laying down a cord (Fig. 3.2B). This technique is suboptimal in deeper folds as it does not address the underlying structural support needed to lift certain areas of the face. Examples of areas to use this method include: nasolabial folds and jawline (Table 3.2). This can also be done using a blunt-tipped cannula.

Fanning

Though the insertion point is similar to the linear-threading technique, in this method the needle is not removed from the skin but rather redirected in various directions in a fan-like motion, laying down product underneath the fold (Fig. 3.2C). A blunt-tipped cannula can be used for this technique, which is excellent to help prop up deep folds by addressing the overhang that occurs from adjacent skin. Examples of areas to use this method include: nasolabial folds, corners of the mouth, and temples (Table 3.2). A combination of linear threading and fanning are commonly used together for volume correction.

Cross-hatching

Several parallel cords are placed in one direction and then overlapped with cords placed perpendicularly creating a strut-like scaffold beneath the fold (Fig. 3.2D). Though the patient will experience several needle sticks and the placement of filler in multiple planes can lead to more bruising, this method is ideal for treatment areas that require significant volume. Examples of areas to use this method include: cheeks, jowls, and marionette lines (Table 3.2). Like the other techniques, this can also be done with a blunt-tipped cannula.

Site-specific treatment strategies

Bachmann F, Erdmann R, Hartmann V. Adverse reactions caused by consecutive injections of different fillers in the same facial region: risk assessment based on the results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2011;25:902–912.

Bellew SG, Carroll KC, Weiss MA, et al. Sterility of stored nonanimal, stabilized hyaluronic acid gel syringes after patient injection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;52:988–990.

Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:893–897.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. A prospective, randomized, parallel group study analyzing the effect of BTX-A (Botox) and nonanimal sourced hyaluronic acid (NASHA™, Restylane) in combination compared with NASHA™ (Restylane) alone in severe glabellar rhytides in adult female subjects: treatment of severe glabellar rhytides with a hyaluronic acid derivative compared with the derivative and BTX-A. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:802–809.

Carruthers A, Carey W, de Lorenzi C, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of efficacy of two hyaluronic acid derivatives, Restylane Perlane and Hylaform, in the treatment of nasolabial folds. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:1591–1598.

Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:S92–S99.

Day DJ, Littler CM, Swift RW, et al. The wrinkle severity rating scale: a validation study. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2004;5:49–52. 2004

Hamilton RG, Strobos J, Adkinson NF. Immunogenicity studies of cosmetically administered nonanimal-stabilized hyaluronic acid particles. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:S176–S185.

Hanke CW, Rohrich RJ, Busso M, et al. Facial soft-tissue fillers conference: assessing the state of the science. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64:S66–S85.

Hexsel D, Brum C, Schilling de Souza J, et al. A phase II, randomized, double-blind clinical trial comparing safety and efficacy of a metallic cannula versus a standard needle for dermal filler injections (hyaluronic acid gel) for the treatment of nasogenian folds. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64:AB164.

Hirsch RJ, Cohen JL, Carruthers JD. Successful management of an unusual presentation of impending necrosis following a hyaluronic acid injection embolus and a proposed algorithm for management with hyaluronidase. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33:357–360.

Kablik J, Monheit GD, Yu L, et al. Comparative physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35:302–312.

Leonhardt JM, Lawrence N, Narins RS. Angioedema acute hypersensitivity reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:577–579.

Lupo MP, Smith SR, Thomas JA, et al. Effectiveness of Juvéderm Ultra Plus dermal filler in the treatment of severe nasolabial folds. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121:289–297.

Matarasso SL, Carruthers JD, Jewell ML, et al. Consensus recommendations for soft-tissue augmentation with nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (Restylane). Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;117:S3–S43.

Monheit GD, Davis B. Nasolabial folds. In: Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Soft tissue augmentation. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2008:105–126.

Monheit GD, Baumann LS, Gold MH, et al. Novel hyaluronic acid derm filler: dermal gel extra physical properties and clinical outcomes. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:1833–1841.

Narins RS, Bowman PH. Injectable skin fillers. Clinical Plastic Surgery. 2005;32:151–162.

Narins RS, Jewell M, Rubin M, et al. Clinical conference: management of rare events following dermal fillers – focal necrosis and angry red bumps. Dermatologic Surgery. 2006;32:426–434.

Narins RS, Coleman WP, Donofrio LM, et al. Improvement in nasolabial folds with a hyaluronic acid filler using a cohesive polydensified matrix technology: results from an 18-month open-label extension trial. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:1800–1808.