Chapter 20 Nasal valve repair

1 INTRODUCTION

The nasal valve is defined as the flow-limiting segment of the nasal airway, located at the triangular aperture between the upper lateral cartilage and the septum. The angle formed by these two structures ranges from 10° to 15 °, and is maintained by the relationships between the nasal septum, the lower lateral cartilage, and the attachments of the facial muscles.1

Nasal valve collapse is a common cause of nasal airway obstruction. In fact, nasal valvular incompetence may equal or even exceed septal deviation as the prime cause of nasal airway obstruction.2 The valve area may be obstructed secondary to surgical procedures (such as rhinoplasty), trauma, or even aging. The complexity of nasal valve repair techniques and its variable results, coupled with the difficulty of treating previously operated patients or even the fact that advanced-age patients often do not seek medical attention for this problem, make nasal valve collapse an issue that oftentimes remains unresolved. In many cases, nasal valve collapse is not diagnosed until surgical treatment, in the form septoplasty or turbinate reduction, fails to relieve symptoms of nasal obstruction, in which case further causes are investigated. It is often impossible to know if the correction of the obstruction caused by a deviated septum and the turbinates actually unmasked an underlying valve collapse problem, or whether the ensuing increased airflow actually makes the valve collapse. Classically, obstruction of the valve area has been attributed to insufficient support of the upper or lower lateral cartilages. This represents true valve collapse. Fixed valve obstruction, however, may be secondary to a persistently deviated caudal septum after septoplasty. In these cases, lateral displacement of the valve area can overcome this obstruction.

Various techniques aimed at correcting nasal valve collapse have been described.3 Techniques designed to lateralize the superior segment of the upper lateral cartilage, involving cartilage and spreader grafts, are effective when this portion has been medially displaced.4,5 Nasal valve obstruction may be secondary to the position of the septum (e.g. after septoplasty), and in selected cases, also amenable for repair using a nasal valve suspension technique.

The original description of a technique for repair of the nasal valve by means of a suspension of the valve to the orbital rim was described by Paniello.6 Significant modifications to this original technique which simplified this technique, and made it safer and equally effective were later introduced by Friedman et al.7 In this chapter, we describe the patient selection criteria and the simplified technique for nasal valve suspension for patients with nasal valve collapse and obstruction. The effect of improved nasal breathing in patients with OSAHS is discussed in detail in Chapter 19.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

In general, four categories of nasal valve obstruction can be identified, based on the involved valve (external or internal), and whether it is always present (fixed), or present during inspiration only (inspiratory, also referred to as nasal valve collapse). It should be noted that both types of obstruction can be present at the same time. While examining the nasal valve, both the external and the internal valves should be visualized, in order to determine the presence of obstruction. The internal valve is located at the level of the border of the upper lateral cartilage and the piriform aperture. Not only can this area be easily distorted during anterior rhinoscopy, it can also be completely overlooked with nasal endoscopy; hence, it should actually be examined prior to the introduction of the speculum or endoscope into the nose. As part of the routine evaluation, patients should be asked to take a deep breath while observing the nasal valve. A normally functioning nasal valve widens together with the nasal alae external dilator muscles, whereas in patients with inspiratory obstruction, the nasal valve collapses during inspiration. Nasal strips (Breathe Right™, CNS Inc., Whippany, NJ) are usually effective in improving airflow by widening the nasal valve area in these patients, and may serve as a kind of confirmatory test to identify potential candidates for nasal valve suspension.

Patients may have nasal valve obstruction secondary to a deviated caudal septal position, which may nevertheless be correctable by valve suspension in selected situations. The decision to correct the valve or the septum is based on the response to the Cottle maneuver, the position of the entire septum, and whether the patient has had previous septal surgery. The Cottle maneuver consists of superolateral traction being applied to the nasofacial groove, and is considered positive when it causes improvement of the nasal airway, as perceived by the patient. A positive Cottle maneuver is an adequate predictor of a successful outcome of nasal valve suspension for the treatment of nasal airway obstruction.8 The area of obstruction can then be identified by intranasal examination at the valve region. Direct superolateral displacement (with a cotton-tip applicator) should significantly improve the patients’ nasal airway. Patients with associated rhinitis or other causes of nasal airway obstruction should be treated appropriately prior to surgery.

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE (OUTLINE OFPROCEDURE)

Several key points simplify the procedure and deserve special mention before describing the technique for nasal valve suspension in detail. The necessary equipment, which includes the bone anchoring device (Mitek Soft Tissue Anchor system™, DePuy Mitek Inc., Raynham, Mass.) and needle (Fig. 20.1), has been carefully tested and chosen based on trial and error, and has proven to be crucial to the simplicity and effectiveness of the technique. The drill bit is included with the disposable bone anchor set, and it fits into the specific drill used for the procedure. The needle is perfectly sized and its contour allows for easy placement of the suture from the orbital rim to the valve area. Equipment or instrument substitutions are likely to complicate these important steps.

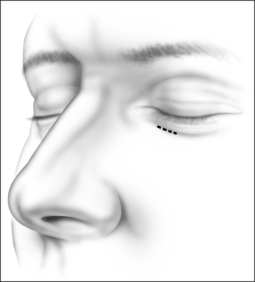

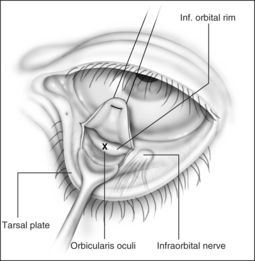

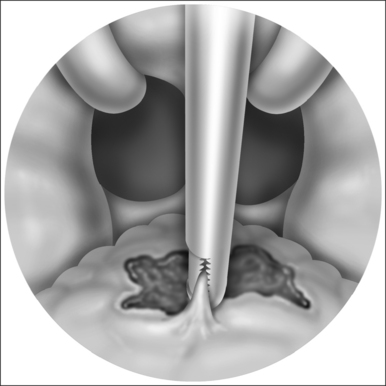

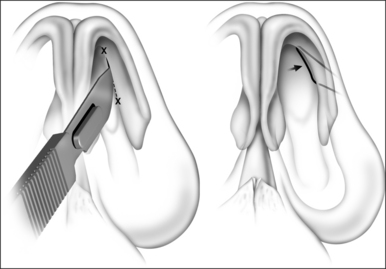

The procedure can be performed under local or general anesthesia. The nasal valve area is examined to identify the area of collapse prior to injection of local anesthesia, in order to avoid tissue distortion. Two points representing the caudal and cephalad margins of the collapsed area are marked, and an incision is made through the mucosa, connecting both points (Fig. 20.2). This mucosal incision is an important modification from a previously reported technique.7 It ensures that the suture, once it is looped at the level of the nasal valve and back into the orbital rim, is buried underneath the healing mucosa, instead of remaining exposed, which used to promote the development of granulation along the valve area in patients who had a reaction to the suture material. A natural skin crease along the orbital rim is also marked (Fig. 20.3), where the incision for the infraorbital approach will be performed. Alternatively, a transconjunctival approach that provides access to the infraorbital rim can be performed on patients who refuse facial incisions (Fig. 20.4). No significant scarring results from the facial incision, however, and since this approach is significantly more direct and simple than the transconjunctival approach, we prefer and recommend the infraorbital approach. Local anesthesia with epinephrine is then injected into the valve area, along the maxilla, near the infraorbital nerve, and along the orbital rim. A 3 mm incision is made in the medial aspect of the orbital rim. The skin incision is carried down through the subcutaneous tissue. The orbicularis oculi muscle fibers are then separated with blunt dissection using a Dunning elevator. The orbital periosteum is exposed, incised, and elevated. Bleeding is rarely encountered, and can be easily controlled with bipolar cautery. The periosteum is elevated away from the orbital rim with two Dunning elevators, in order to expose a 3 × 3 mm area. The bone anchor system is used to anchor the suture to this exposed area in the orbital rim. The drill bit included with the bone anchor system is compatible with the battery-operated Stryker™ (Kalamazoo, MI) drill. A small drill hole is made into the bone, with or without a guide, and the anchor is easily inserted into the bone (Fig. 20.5). Should the drill hole enter the maxillary sinus, the anchor should not be placed, since the thin bone will not provide adequate support. It is crucial for the anchor to be placed at the orbital rim, where the bone is thick enough to engage the anchor. The anchor is designed to be placed beneath the bone surface, thus eliminating the possibility of protruding above the surface and causing symptoms. The longer end of the suture (3-0 Ethibond™, Ethicon, Sommerville, NJ) is then passed with a curved, tapered needle (Fig. 20.6) into the nasal valve area and passed through the incised mucosa (Fig. 20.7). After identifying the site of collapse and the intended site of suspension, the needle is then ret-hreaded and passed through the opening in the mucosa and toward the anchor (Fig. 20.8). Another important technical point is for the needle and suture to ‘hug’ the periosteum of the maxilla, so that the suture is along the surface of the bone and not running through the subcutaneous tissue. Subcutaneous placement can cause pain or discomfort. The suture is then tightened and tied with the amount of tension necessary to ensure support of the valve, but avoiding significant distortion of the external valve area. The suture is buried underneath the incised mucosa, which avoids the development of granulation tissue. The orbital rim incision is closed with Steri-strips (3 M, St Paul, MN). Although usually only one bone anchor and suture are needed on each affected side, some patients may require additional suspension with two anchors and their corresponding sutures on a single side. The orbicularis oculi fibers are not sutured to avoid ectropion. Patients are told to expect some fullness in the nasofacial groove. The vast majority of patients find this tolerable, and patients reluctant to tolerate this side effect of the procedure should be counseled against undergoing nasal valve suspension.

Fig. 20.2 An incision is made through the mucosa in the previously identified area of internal valve collapse.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

Due to the simplicity of this procedure, patients can be discharged on the same day, with a 1-week postoperative follow-up appointment. Patients usually receive a prescription for postoperative antibiotics for 5–7 days, and are instructed to take over-the-counter analgesics in case of significant postoperative pain. No additional postoperative instructions are necessary. Nasal valve suspension does not require postoperative packing, which not only makes the postoperative course much more comfortable for the patient, but it also eliminates an important source of morbidity when combined with other procedures, like uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, in patients who undergo combined procedures for OSAHS.9 For this same reason, nasal valve suspension allows for the resumption of nasal continuous positive airway pressure during the immediate postoperative period, if necessary.

In general, no major complications have been identified. Minor complications include, but are not limited to, persistent pain at the orbital suspension site, which may require removal of the suture. This pain might be due to the close proximity to the infraorbital nerve, which may be confirmed by means of a computed tomography (CT) scan. This is a rare complication, since the placement of the anchor is usually 2.5 cm medial to the infraorbital nerve. The pain intensity may range from vague discomfort or a sensation of fullness to significant pain, and should be addressed appropriately. The more likely cause of persistent pain is the subcutaneous placement of the suture, which pulls on the tissues. This symptom usually resolves after removal of the suture. Implant removal is more difficult and almost never required. Infection and abscess formation is a rare complication. Should they present, incision and drainage of the abscess, together with suture removal, will appropriately resolve these complications. In most cases, a change in the external appearance of the nose is considered inconsequential by patients. Scars at the infraorbital level are, likewise, not considered significant. The overall rate of complications, requiring suture removal, is about 3%, as described by Friedman et al.8 It is also important to note that this procedure is completely reversible, and that the common complications can be addressed in an outpatient setting. Removal of the suture is more difficult than placement of the suture, but can be performed with local anesthesia. Suture removal will almost always resolve uncontrolled infection, pain, or deformity. It is rarely necessary to remove the bone anchor, which could require drilling of the surrounding bone.

5 SUCCESS RATE OF THE PROCEDURE

Over 90% of patients who experience relief of nasal airway obstruction by using breathing strips report subjective improvement after nasal valve suspension, based on short- and long-term studies (6-month follow-up). As measured by standardized symptom and quality-of-life questionnaires specifically designed to assess nasal obstruction symptoms,10 significant improvement has also been shown in over 80% of patients who underwent bilateral nasal valve suspension, even considering the fact that some of the most popular instruments used, like the Sino-nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20), do not specifically explore symptoms relative to nasal stuffiness or obstruction. Objective improvement, as shown by comparing pre- and postoperative nasal cross-sectional area (CSA) with acoustic rhinometry (AR) for the left and right nasal cavities, also has shown consistent and significant improvement. AR is probably not valuable as an isolated diagnostic test in evaluating nasal valve obstruction due to its wide range of normal values.11,12 It does, however, provide a good objective value for comparison, and to establish improvement. Improvement of CSA correlates with subjective improvement in relief of nasal obstruction. Nasal valve suspension can also be combined with other airway procedures, when performed for the surgical treatment of OSAHS, and this significantly impacts the effectiveness of nasal obstruction relief in the treatment of such patients (see Chapter 19). A significant number of patients will undergo nasal valve suspension after having previously undergone procedures like rhino- or septoplasty, or even endonasal repair attempts with alar cartilage or spreader grafts for persistent nasal obstruction. These patients also show significant improvement after nasal valve suspension, and find this surgical alternative more acceptable than additional endonasal surgery, mostly because of the possibility of undergoing the procedure with local anesthesia only, not requiring postoperative packing or splinting, and not having the potential for donor site morbidity, as is the case for cartilage-grafting techniques. Long-term controlled studies have not been done, and the success rate of the procedure would likely drop after longer follow-up.

1. Bridger G. Physiology of the nasal valve. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;92:543-553.

2. Constantian M, Clardy R. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:38-54. discussion 55–8.

3. Goode R. Surgery of the incompetent nasal valve. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:546-555.

4. Lee D, Glasgold A. Correction of nasal valve stenosis with lateral suture suspension. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:237-240.

5. Sheen J. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:230-239.

6. Paniello R. Nasal valve suspension. An effective treatment for nasal valve collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1342-1346.

7. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Syed Z. Nasal valve suspension: an improved, simplified technique for nasal valve collapse. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:381-385.

8. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lee G, et al. A simplified technique for airway correction at the nasal valve area. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:519-524.

9. Dorn M, Pirsig W, Verse T. [Postoperative management following rhinosurgery interventions in severe obstructive sleep apnea. A pilot study]. HNO. 2001;49:642-645.

10. Piccirillo J, Merritt MJ, Richards M. Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:41-47.

11. Corey J, Gungor A, Nelson R, et al. A comparison of the nasal cross-sectional areas and volumes obtained with acoustic rhinometry and magnetic resonance imaging. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:349-354.

12. Hamilton J, McRae R, Phillips D, et al. The accuracy of acoustic rhinometry using a pulse train signal. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1995;20:279-282.