Chapter 25

Myocarditis

2. What is the pathogenesis of myocarditis?

Phase 1, sometimes called acute viral, occurs after viral entry and proliferation in the myocardium and results in direct tissue injury even before an inflammatory reaction.

Phase 1, sometimes called acute viral, occurs after viral entry and proliferation in the myocardium and results in direct tissue injury even before an inflammatory reaction.

Phase 2, called subacute immune, is characterized by activation of the innate and acquired immune response. The innate immune response leads to upregulation of a variety of inflammatory mediators like interferons, tumor necrosis factor, and nitric oxide, which ultimately result in an influx of tissue-specific T and B cells (acquired immune response) into the heart. If the inflammatory response persists, a chronic myopathic phase (phase 3) with fibrosis and remodeling with dilation of the ventricles may develop in susceptible individuals.

Phase 2, called subacute immune, is characterized by activation of the innate and acquired immune response. The innate immune response leads to upregulation of a variety of inflammatory mediators like interferons, tumor necrosis factor, and nitric oxide, which ultimately result in an influx of tissue-specific T and B cells (acquired immune response) into the heart. If the inflammatory response persists, a chronic myopathic phase (phase 3) with fibrosis and remodeling with dilation of the ventricles may develop in susceptible individuals.

In phase 3, immune activation may persist and contribute to progressive cardiomyopathy.

In phase 3, immune activation may persist and contribute to progressive cardiomyopathy.

In any phase, inflammation and fibrosis may lead to ventricular arrhythmias or heart block.

3. What is the clinical presentation of myocarditis?

In contrast to adults with myocarditis, children often have a more fulminant presentation and may require advanced circulatory support for ventricular failure in early stages of their disease. Despite a severe presentation, recovery after a period of hemodynamic support is not uncommon.

4. What is the incidence of myocarditis and who does it affect?

5. What are the causative agents of myocarditis?

Myocarditis can be triggered by many infectious pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, Chlamydia, rickettsia, fungi, and protozoans, as well as systemic toxic and hypersensitivity reactions (Table 25-1).

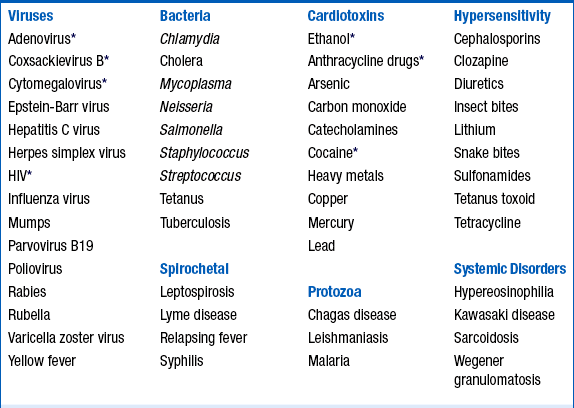

TABLE 25-1

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

∗Frequent cause of myocarditis.

From Elamm C, Fairweather D, Cooper LT: Pathogenesis and diagnosis of myocarditis, Heart 98:835-840, 2012.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause myocarditis in patients posttransplant and early infection posttransplant correlates with coronary allograft vasculopathy.

6. What are some of the clinical presentations of nonviral infectious myocarditis?

Bacteria: Bacterial myocarditis is far less common than viral-induced myocarditis. Corynebacterium diphtheriae can cause myocarditis associated with bradycardia in people not previously immunized. Clostridium organisms and bacteremia from any source may result in endocarditis and adjacent myocarditis. Other bacterial pathogens to consider include meningococci, streptococci, and Listeria organisms.

Bacteria: Bacterial myocarditis is far less common than viral-induced myocarditis. Corynebacterium diphtheriae can cause myocarditis associated with bradycardia in people not previously immunized. Clostridium organisms and bacteremia from any source may result in endocarditis and adjacent myocarditis. Other bacterial pathogens to consider include meningococci, streptococci, and Listeria organisms.

Spirochetes: The tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease. The initial infection is often marked by a rash followed in weeks or months by involvement of other organ systems, including the heart and nervous system, and joints. Heart block or symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias in the setting of cardiomyopathy should raise suspicion for Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas such as parts of New England or the upper Mississippi River valley. Full recovery is typical, although carditis sometimes persists. Co-infection with Ehrlichia organisms has been reported.

Spirochetes: The tick-borne spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease. The initial infection is often marked by a rash followed in weeks or months by involvement of other organ systems, including the heart and nervous system, and joints. Heart block or symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias in the setting of cardiomyopathy should raise suspicion for Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas such as parts of New England or the upper Mississippi River valley. Full recovery is typical, although carditis sometimes persists. Co-infection with Ehrlichia organisms has been reported.

Protozoa: Infection with the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi causes Chagas disease, which is encountered in Central and South America. It may be transmitted by direct inoculation by reduviid insects, through blood transfusions, or, rarely, oral inoculation. Chagas disease can present as acute myocarditis, but more commonly presents as a chronic cardiomyopathy characterized by segmental wall motion abnormalities, apical aneurysms, and ECG changes, including right bundle branch block (RBBB), left anterior fascicular block (LAFB), and AV block.

Protozoa: Infection with the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi causes Chagas disease, which is encountered in Central and South America. It may be transmitted by direct inoculation by reduviid insects, through blood transfusions, or, rarely, oral inoculation. Chagas disease can present as acute myocarditis, but more commonly presents as a chronic cardiomyopathy characterized by segmental wall motion abnormalities, apical aneurysms, and ECG changes, including right bundle branch block (RBBB), left anterior fascicular block (LAFB), and AV block.

7. What is giant cell myocarditis?

8. What are the ECG findings in myocarditis?

9. What are the echocardiographic findings in myocarditis?

There are no specific echocardiographic features of myocarditis. Echocardiography is used mainly to exclude other causes of heart failure, such as valvular, congenital, or pericardial disease. Impaired right ventricular (RV) function is an independent predictor of death or the need for cardiac transplantation. Patients with fulminant myocarditis tend to present with near normal cardiac chamber dimensions and thickened walls compared with patients with a longer duration of symptoms who have greater left ventricular (LV) dilation and normal wall thickness. Patients who meet the clinicopathologic criteria for fulminant myocarditis have a greater rate of full recovery if they survive their initial illness. Therefore, echocardiography has a value in classifying patients with acute myocarditis and may provide prognostic information.

10. Are cardiac biomarkers useful?

11. Are inflammatory markers and viral serology useful?

12. What is the gold standard to diagnose myocarditis?

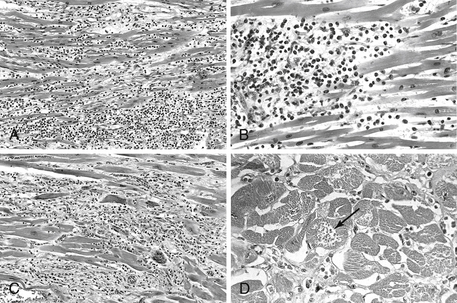

Figure 25-1 presents histologic examples of myocarditis.

Figure 25-1 Myocarditis. A, Lymphocytic myocarditis, associated with myocyte injury. B, Hypersensitivity myocarditis, characterized by interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed largely of eosinophils and mononuclear inflammatory cells, predominantly localized to perivascular and expanded interstitial spaces. C, Giant cell myocarditis, with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate containing lymphocytes and macrophages, extensive loss of muscle and multinucleated giant cells. D, The myocarditis of Chagas disease. A myofiber distended with trypanosomes (arrow) is present along with inflammation and necrosis of individual myofibers. (From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic basis of disease, professional edition, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2009, Saunders.

13. Should an endomyocardial biopsy be performed on every patient with suspected myocarditis?

EMB should be performed in that subset of adults who present with recent-onset severe heart failure requiring inotropic or mechanical circulatory support within two weeks of a viral illness, because they frequently can be bridged to recovery if they have lymphocytic myocarditis.

EMB should be performed in that subset of adults who present with recent-onset severe heart failure requiring inotropic or mechanical circulatory support within two weeks of a viral illness, because they frequently can be bridged to recovery if they have lymphocytic myocarditis.

Patients who present with fulminant or acute dilated cardiomyopathy with sustained or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia or high-degree heart block, or who fail to respond to standard heart failure treatment should be biopsied for possible giant cell myocarditis. The sensitivity of biopsy in this setting is reported to range between 80% and 85%.

Patients who present with fulminant or acute dilated cardiomyopathy with sustained or symptomatic ventricular tachycardia or high-degree heart block, or who fail to respond to standard heart failure treatment should be biopsied for possible giant cell myocarditis. The sensitivity of biopsy in this setting is reported to range between 80% and 85%.

14. Is there a role for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) in myocarditis?

15. What is the treatment of lymphocytic myocarditis?

The mainstay of treatment for myocarditis presenting as recent-onset dilated cardiomyopathy is supportive therapy for LV dysfunction. Most patients with acute myocarditis presenting with dilated cardiomyopathy respond well to standard heart failure therapy, including diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists, as well as treatment with β-blockers once clinically stabilized.

16. Is there a role for antiviral and immunosuppressive therapy?

17. When does the patient with myocarditis need mechanical circulatory support and when should patients be considered for cardiac transplantation?

Mechanical circulatory support may be effective in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock despite optimal medical intervention. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support may be beneficial for adult and pediatric patients with fulminant myocarditis and profound shock, as short-term recovery can occur within days. For patients with cardiogenic shock due to acute myocarditis who deteriorate despite optimal medical management, recovery is more likely to be prolonged, and implantation of a ventricular assist device as a bridge to transplantation or recovery may be a more effective alternative. For those patients who are refractory to medical therapy and mechanical circulatory support, cardiac transplantation should be considered. The overall rate of survival after cardiac transplantation for myocarditis in adults is similar to that for other causes of cardiac failure.