459 |

Peripheral Neuropathy |

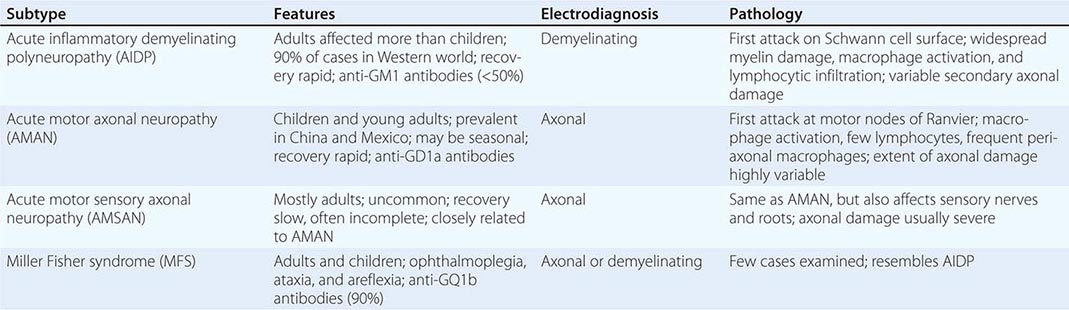

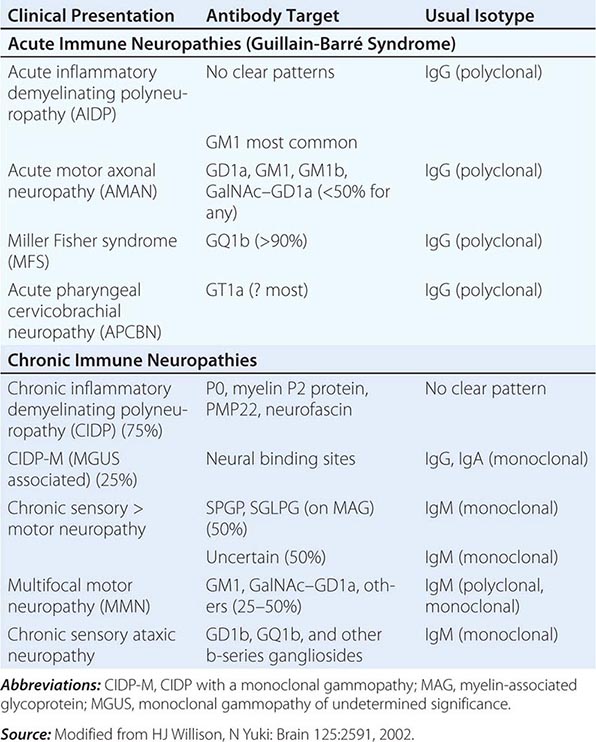

Peripheral nerves are composed of sensory, motor, and autonomic elements. Diseases can affect the cell body of a neuron or its peripheral processes, namely the axons or the encasing myelin sheaths. Most peripheral nerves are mixed and contain sensory and motor as well as autonomic fibers. Nerves can be subdivided into three major classes: large myelinated, small myelinated, and small unmyelinated. Motor axons are usually large myelinated fibers that conduct rapidly (approximately 50 m/s). Sensory fibers may be any of the three types. Large-diameter sensory fibers conduct proprioception and vibratory sensation to the brain, while the smaller-diameter myelinated and unmyelinated fibers transmit pain and temperature sensation. Autonomic nerves are also small in diameter. Thus, peripheral neuropathies can impair sensory, motor, or autonomic function, either singly or in combination. Peripheral neuropathies are further classified into those that primarily affect the cell body (e.g., neuronopathy or ganglionopathy), myelin (myelinopathy), and the axon (axonopathy). These different classes of peripheral neuropathies have distinct clinical and electrophysiologic features. This chapter discusses the clinical approach to a patient suspected of having a peripheral neuropathy, as well as specific neuropathies, including hereditary and acquired neuropathies. The inflammatory neuropathies are discussed in Chap. 460.

GENERAL APPROACH

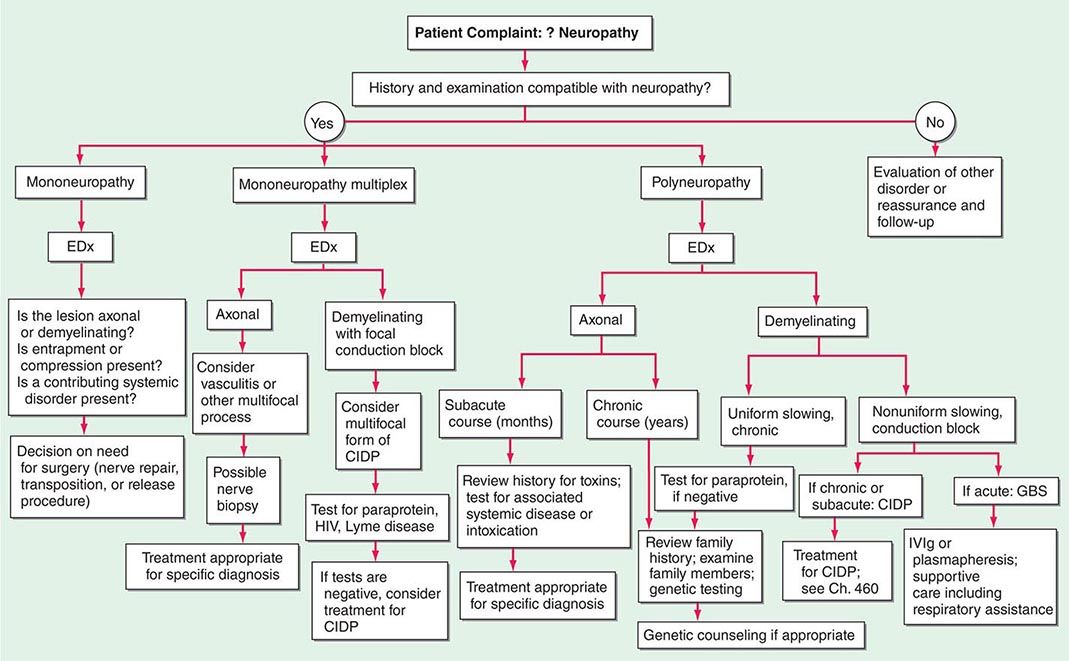

In approaching a patient with a neuropathy, the clinician has three main goals: (1) identify where the lesion is, (2) identify the cause, and (3) determine the proper treatment. The first goal is accomplished by obtaining a thorough history, neurologic examination, and electrodiagnostic and other laboratory studies (Fig. 459-1). While gathering this information, seven key questions are asked (Table 459-1), the answers to which can usually identify the category of pathology that is present (Table 459-2). Despite an extensive evaluation, in approximately half of patients, no etiology is ever found; these patients typically have a predominately sensory polyneuropathy and have been labeled as having idiopathic or cryptogenic sensory polyneuropathy (CSPN).

FIGURE 459-1 Approach to the evaluation of peripheral neuropathies. CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; EDx, electrodiagnostic; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin.

|

APPROACH TO NEUROPATHIC DISORDERS: SEVEN KEY QUESTIONS |

|

PATTERNS OF NEUROPATHIC DISORDERS |

Abbreviations: CIDP, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy; CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; CMV, cytomegalovirus; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HNA, hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy; HNPP, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies; HSAN, hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

INFORMATION FROM THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION: SEVEN KEY QUESTIONS (TABLE 459-1)

1. What Systems are Involved? It is important to determine if the patient’s symptoms and signs are motor, sensory, autonomic, or a combination of these. If the patient has only weakness without any evidence of sensory or autonomic dysfunction, a motor neuropathy, neuromuscular junction abnormality, or myopathy should be considered. Some peripheral neuropathies are associated with significant autonomic nervous system dysfunction. Symptoms of autonomic involvement include fainting spells or orthostatic lightheadedness; heat intolerance; or any bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction (Chap. 454). There will typically be an orthostatic fall in blood pressure without an appropriate increase in heart rate. Autonomic dysfunction in the absence of diabetes should alert the clinician to the possibility of amyloid polyneuropathy. Rarely, a pandysautonomic syndrome can be the only manifestation of a peripheral neuropathy without other motor or sensory findings. The majority of neuropathies are predominantly sensory in nature.

2. What is the Distribution of Weakness? Delineating the pattern of weakness, if present, is essential for diagnosis, and in this regard two additional questions should be answered: (1) Does the weakness only involve the distal extremity, or is it both proximal and distal? and (2) Is the weakness focal and asymmetric, or is it symmetric? Symmetric proximal and distal weakness is the hallmark of acquired immune demyelinating polyneuropathies, both the acute form (acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy [AIDP], also known as Guillain-Barré syndrome [GBS]) and the chronic form (chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy [CIDP]). The importance of finding symmetric proximal and distal weakness in a patient who presents with both motor and sensory symptoms cannot be overemphasized because this identifies the important subset of patients who may have a treatable acquired demyelinating neuropathic disorder (i.e., AIDP or CIDP).

Findings of an asymmetric or multifocal pattern of weakness narrow the differential diagnosis. Some neuropathic disorders may present with unilateral extremity weakness. In the absence of sensory symptoms and signs, such weakness evolving over weeks or months would be worrisome for motor neuron disease (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]), but it would be important to exclude multifocal motor neuropathy that may be treatable (Chap. 452). In a patient presenting with asymmetric subacute or acute sensory and motor symptoms and signs, radiculopathies, plexopathies, compressive mononeuropathies, or multiple mononeuropathies (e.g., mononeuropathy multiplex) must be considered.

3. What is the Nature of the Sensory Involvement? The patient may have loss of sensation (numbness), altered sensation to touch (hyperpathia or allodynia), or uncomfortable spontaneous sensations (tingling, burning, or aching) (Chap. 31). Neuropathic pain can be burning, dull, and poorly localized (protopathic pain), presumably transmitted by polymodal C nociceptor fibers, or sharp and lancinating (epicritic pain), relayed by A-delta fibers. If pain and temperature perception are lost, while vibratory and position sense are preserved along with muscle strength, deep tendon reflexes, and normal nerve conduction studies, a small-fiber neuropathy is likely. This is important, because the most likely cause of small-fiber neuropathies, when one is identified, is diabetes mellitus or glucose intolerance. Amyloid neuropathy should be considered as well in such cases, but most of these small-fiber neuropathies remain idiopathic in nature despite extensive evaluation.

Severe proprioceptive loss also narrows the differential diagnosis. Affected patients will note imbalance, especially in the dark. A neurologic examination revealing a dramatic loss of proprioception with vibration loss and normal strength should alert the clinician to consider a sensory neuronopathy/ganglionopathy (Table 459-2, Pattern 8). In particular, if this loss is asymmetric or affects the arms more than the legs, this pattern suggests a non-length-dependent process as seen in sensory neuronopathies.

4. Is There Evidence of Upper Motor Neuron Involvement? If the patient presents with symmetric distal sensory symptoms and signs suggestive of a distal sensory neuropathy, but there is additional evidence of symmetric upper motor neuron involvement (Chap. 30), the physician should consider a disorder such as combined system degeneration with neuropathy. The most common cause for this pattern is vitamin B12 deficiency, but other causes of combined system degeneration with neuropathy should be considered (e.g., copper deficiency, HIV infection, severe hepatic disease, adrenomyeloneuropathy).

5. What is the Temporal Evolution? It is important to determine the onset, duration, and evolution of symptoms and signs. Does the disease have an acute (days to 4 weeks), subacute (4–8 weeks), or chronic (>8 weeks) course? Is the course monophasic, progressive, or relapsing? Most neuropathies are insidious and slowly progressive in nature. Neuropathies with acute and subacute presentations include GBS, vasculitis, and radiculopathies related to diabetes or Lyme disease. A relapsing course can be present in CIDP and porphyria.

6. Is There Evidence for a Hereditary Neuropathy? In patients with slowly progressive distal weakness over many years with very little in the way of sensory symptoms yet with significant sensory deficits on clinical examination, the clinician should consider a hereditary neuropathy (e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [CMT]). On examination, the feet may show arch and toe abnormalities (high or flat arches, hammertoes); scoliosis may be present. In suspected cases, it may be necessary to perform both neurologic and electrophysiologic studies on family members in addition to the patient.

7. Does the Patient Have Any Other Medical Conditions? It is important to inquire about associated medical conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus); preceding or concurrent infections (e.g. diarrheal illness preceding GBS); surgeries (e.g., gastric bypass and nutritional neuropathies); medications (toxic neuropathy), including over-the-counter vitamin preparations (B6); alcohol; dietary habits; and use of dentures (e.g., fixatives contain zinc that can lead to copper deficiency).

PATTERN RECOGNITION APPROACH TO NEUROPATHIC DISORDERS

Based on the answers to the seven key questions, neuropathic disorders can be classified into several patterns based on the distribution or pattern of sensory, motor, and autonomic involvement (Table 459-2). Each pattern has a limited differential diagnosis. A final diagnosis is established by using other clues such as the temporal course, presence of other disease states, family history, and information from laboratory studies.

ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

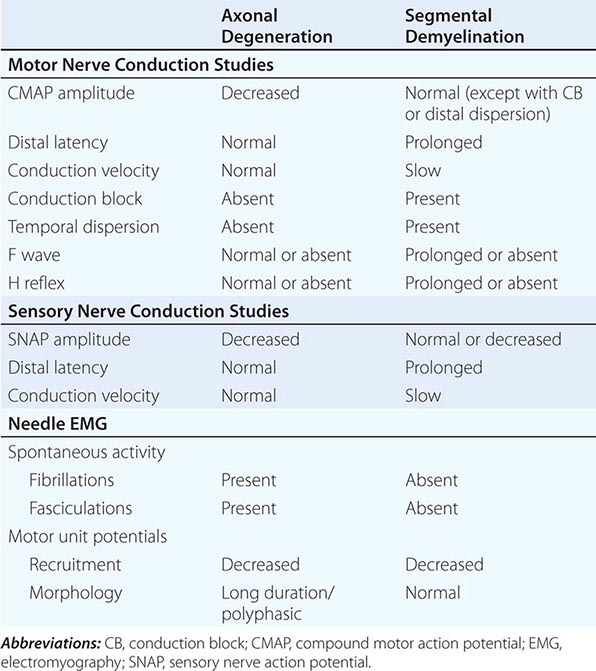

The electrodiagnostic (EDx) evaluation of patients with a suspected peripheral neuropathy consists of nerve conduction studies (NCS) and needle electromyography (EMG). In addition, studies of autonomic function can be valuable. The electrophysiologic data provide additional information about the distribution of the neuropathy that will support or refute the findings from the history and physical examination; they can confirm whether the neuropathic disorder is a mononeuropathy, multiple mononeuropathy (mononeuropathy multiplex), radiculopathy, plexopathy, or generalized polyneuropathy. Similarly, EDx evaluation can ascertain whether the process involves only sensory fibers, motor fibers, autonomic fibers, or a combination of these. Finally, the electrophysiologic data can help distinguish axonopathies from myelinopathies as well as axonal degeneration secondary to ganglionopathies from the more common length-dependent axonopathies.

NCS are most helpful in classifying a neuropathy as being due to axonal degeneration or segmental demyelination (Table 459-3). In general, low-amplitude potentials with relatively preserved distal latencies, conduction velocities, and late potentials, along with fibrillations on needle EMG, suggest an axonal neuropathy. On the other hand, slow conduction velocities, prolonged distal latencies and late potentials, relatively preserved amplitudes, and the absence of fibrillations on needle EMG imply a primary demyelinating neuropathy. The presence of nonuniform slowing of conduction velocity, conduction block, or temporal dispersion further suggests an acquired demyelinating neuropathy (e.g., GBS or CIDP) as opposed to a hereditary demyelinating neuropathy (e.g., CMT type 1).

|

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGIC FEATURES: AXONAL DEGENERATION VERSUS SEGMENTAL DEMYELINATION |

Autonomic studies are used to assess small myelinated (A-delta) or unmyelinated (C) nerve fiber involvement. Such testing includes heart rate response to deep breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure response to both the Valsalva maneuver and tilt-table testing and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing (Chap. 454). These studies are particularly useful in patients who have pure small-fiber neuropathy or autonomic neuropathy in which routine NCS are normal.

OTHER IMPORTANT LABORATORY INFORMATION

In patients with generalized symmetric peripheral neuropathy, a standard laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count, basic chemistries including serum electrolytes and tests of renal and hepatic function, fasting blood glucose (FBS), HbA1c, urinalysis, thyroid function tests, B12, folate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunoelectrophoresis or immunofixation, and urine for Bence Jones protein. Quantification of the concentration of serum free light chains and the kappa/lambda ratio is more sensitive than SPEP, immunoelectrophoresis, or immunofixation in looking for a monoclonal gammopathy and therefore should be done if one suspects amyloidosis. A skeletal survey should be performed in patients with acquired demyelinating neuropathies and M-spikes to look for osteosclerotic or lytic lesions. Patients with monoclonal gammopathy should also be referred to a hematologist for consideration of a bone marrow biopsy. An oral glucose tolerance test is indicated in patients with painful sensory neuropathies even if FBS and HbA1c are normal, as the test is abnormal in about one-third of such patients. In addition to the above tests, patients with a mononeuropathy multiplex pattern of involvement should have a vasculitis workup, including antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), cryoglobulins, hepatitis serology, Western blot for Lyme disease, HIV, and occasionally a cytomegalovirus (CMV) titer.

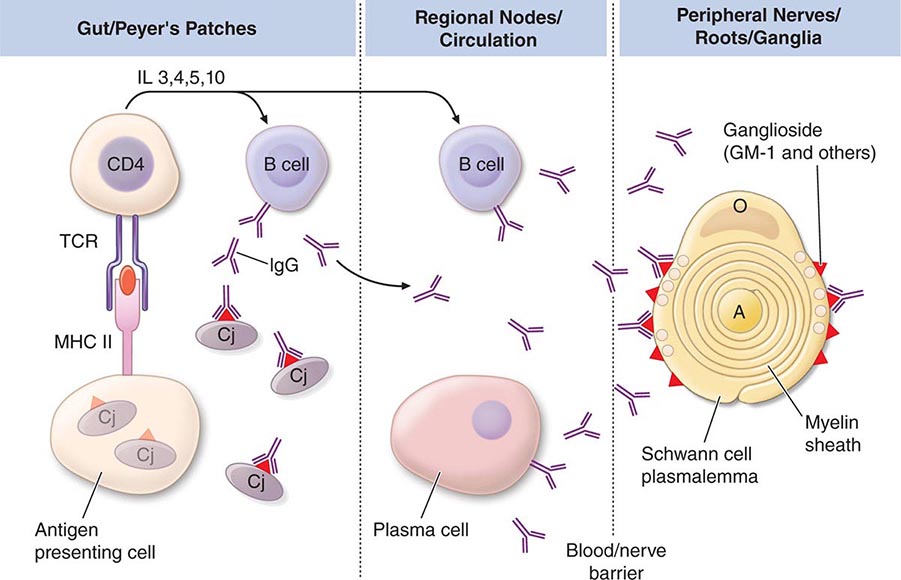

There are many autoantibody panels (various antiganglioside antibodies) marketed for screening routine neuropathy patients for a treatable condition. These autoantibodies have no proven clinical utility or added benefit beyond the information obtained from a complete clinical examination and detailed EDx. A heavy metal screen is also not necessary as a screening procedure, unless there is a history of possible exposure or suggestive features on examination (e.g., severe painful sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy and alopecia—thallium; severe painful sensorimotor neuropathy with or without gastrointestinal [GI] disturbance and Mee’s lines—arsenic; wrist or finger extensor weakness and anemia with basophilic stippling of red blood cells—lead).

In patients with suspected GBS or CIDP, a lumbar puncture is indicated to look for an elevated cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) protein. In idiopathic cases of GBS and CIDP, there should not be pleocytosis in the CSF. If cells are present, one should consider HIV infection, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, or lymphomatous or leukemic infiltration of nerve roots. Some patients with GBS and CIDP have abnormal liver function tests. In these cases, it is important to also check for hepatitis B and C, HIV, CMV, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. In patients with an axonal GBS (by EMG/NCS) or those with a suspicious coinciding history (e.g., unexplained abdominal pain, psychiatric illness, significant autonomic dysfunction), it is reasonable to screen for porphyria.

In patients with a severe sensory ataxia, a sensory ganglionopathy or neuronopathy should be considered. The most common causes of sensory ganglionopathies are Sjögren’s syndrome and a paraneoplastic neuropathy. Neuropathy can be the initial manifestation of Sjögren’s syndrome. Thus, one should always inquire about dry eyes and mouth in patients with sensory signs and symptoms. Further, some patients can manifest sicca complex without full-blown Sjögren’s syndrome. Thus, patients with sensory ataxia should have a senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA) and single strand binding (SSB) in addition to the routine ANA. To work up a possible paraneoplastic sensory ganglionopathy, antineuronal nuclear antibodies (e.g., anti-Hu antibodies) should be obtained (Chap. 122). These antibodies are most commonly seen in patients with small-cell carcinoma of the lung but are seen also in breast, ovarian, lymphoma, and other cancers. Importantly, the paraneoplastic neuropathy can precede the detection of the cancer, and detection of these autoantibodies should lead to a search for malignancy.

NERVE BIOPSIES

Nerve biopsies are now rarely indicated for evaluation of neuropathies. The primary indication for nerve biopsy is suspicion for amyloid neuropathy or vasculitis. In most instances, the abnormalities present on biopsies do not help distinguish one form of peripheral neuropathy from another (beyond what is already apparent by clinical examination and the NCS). Nerve biopsies should only be done if the NCS are abnormal. The sural nerve is most commonly biopsied because it is a pure sensory nerve and biopsy will not result in loss of motor function. In suspected vasculitis, a combination biopsy of a superficial peroneal nerve (pure sensory) and the underlying peroneus brevis muscle obtained from a single small incision increases the diagnostic yield. Tissue can be analyzed by frozen section and paraffin section to assess the supporting structures for evidence of inflammation, vasculitis, or amyloid deposition. Semithin plastic sections, teased fiber preparations, and electron microscopy are used to assess the morphology of the nerve fibers and to distinguish axonopathies from myelinopathies.

SKIN BIOPSIES

Skin biopsies are sometimes used to diagnose a small-fiber neuropathy. Following a punch biopsy of the skin in the distal lower extremity, immunologic staining can be used to measure the density of small unmyelinated fibers. The density of these nerve fibers is reduced in patients with small-fiber neuropathies in whom NCS and routine nerve biopsies are often normal. This technique may allow for an objective measurement in patients with mainly subjective symptoms. However, it adds little to what one already knows from the clinical examination and EDx.

SPECIFIC DISORDERS

HEREDITARY NEUROPATHIES

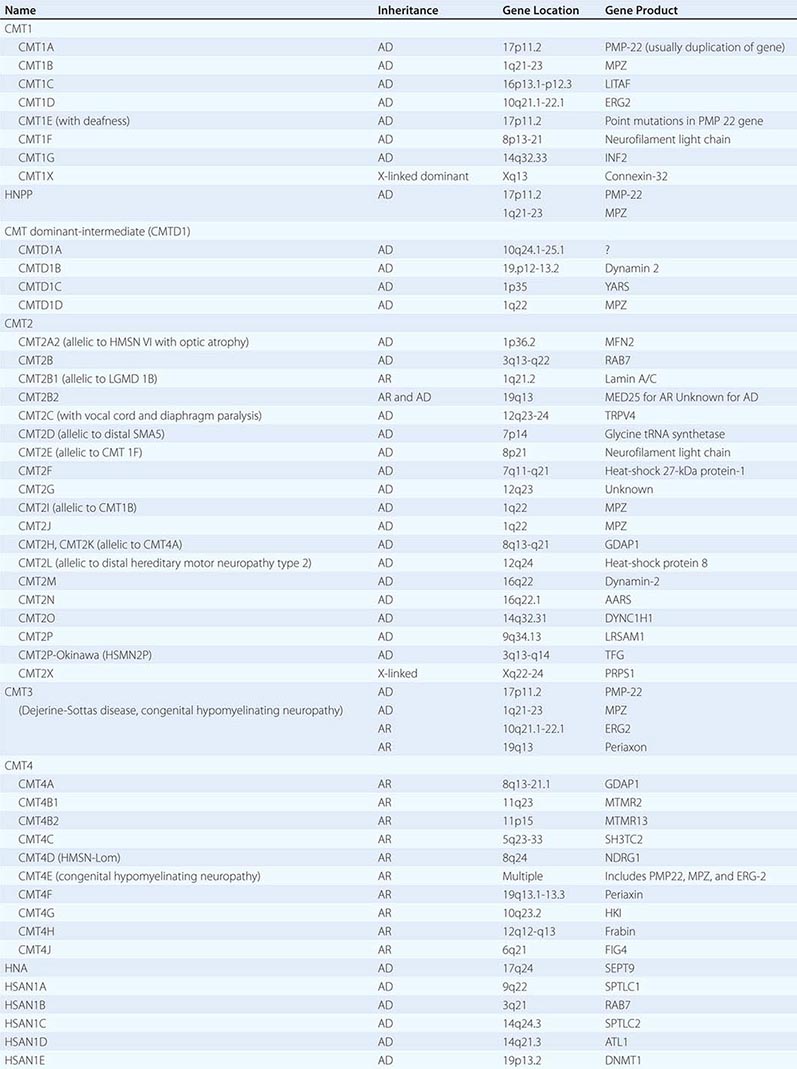

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease is the most common type of hereditary neuropathy. Rather than one disease, CMT is a syndrome of several genetically distinct disorders (Table 459-4). The various subtypes of CMT are classified according to the nerve conduction velocities and predominant pathology (e.g., demyelination or axonal degeneration), inheritance pattern (autosomal dominant, recessive, or X-linked), and the specific mutated genes. Type 1 CMT (or CMT1) refers to inherited demyelinating sensorimotor neuropathies, whereas the axonal sensory neuropathies are classified as CMT2. By definition, motor conduction velocities in the arms are slowed to less than 38 m/s in CMT1 and are greater than 38 m/s in CMT2. However, most cases of CMT1 actually have motor nerve conduction velocities (NCVs) between 20 and 25 m/s. CMT1 and CMT2 usually begin in childhood or early adult life; however, onset later in life can occur, particularly in CMT2. Both are associated with autosomal dominant inheritance, with a few exceptions. CMT3 is an autosomal dominant neuropathy that appears in infancy and is associated with severe demyelination or hypomyelination. CMT4 is an autosomal recessive neuropathy that typically begins in childhood or early adult life. There are no medical therapies for any of the CMTs, but physical and occupational therapy can be beneficial, as can bracing (e.g., ankle-foot orthotics for footdrop) and other orthotic devices.

|

CLASSIFICATION OF CHARCOT-MARIE-TOOTH DISEASE AND RELATED NEUROPATHIES |

CMT1 CMT1 is the most common form of hereditary neuropathy, with the ratio of CMT1:CMT2 being approximately 2:1. Affected individuals usually present in the first to third decade of life with distal leg weakness (e.g., footdrop), although patients may remain asymptomatic even late in life. People with CMT generally do not complain of numbness or tingling, which can be helpful in distinguishing CMT from acquired forms of neuropathy in which sensory symptoms usually predominate. Although usually asymptomatic in this regard, reduced sensation to all modalities is apparent on examination. Muscle stretch reflexes are unobtainable or reduced throughout. There is often atrophy of the muscles below the knee (particularly the anterior compartment), leading to so-called inverted champagne bottle legs.

Motor NCVs are usually in the 20–25 m/s range. Nerve biopsies usually are not performed on patients suspected of having CMT1, because the diagnosis usually can be made by less invasive testing (e.g., NCS and genetic studies). However, when done, the biopsies reveal reduction of myelinated nerve fibers with a predilection for the loss of the large-diameter fibers and Schwann cell proliferation around thinly or demyelinated fibers, forming so-called onion bulbs.

CMT1A is the most common subtype of CMT1, representing 70% of cases, and is caused by a 1.5-megabase (Mb) duplication within chromosome 17p11.2-12 wherein the gene for peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP-22) lies. This results in patients having three copies of the PMP-22 gene rather than two. This protein accounts for 2–5% of myelin protein and is expressed in compact portions of the peripheral myelin sheath. Approximately 20% of patients with CMT1 have CMT1B, which is caused by mutations in the myelin protein zero (MPZ). CMT1B is for the most part clinically, electrophysiologically, and histologically indistinguishable from CMT1A. MPZ is an integral myelin protein and accounts for more than half of the myelin protein in peripheral nerves. Other forms of CMT1 are much less common and again indistinguishable from one another clinically and electrophysiologically.

CMT2 CMT2 tends to present later in life compared to CMT1. Affected individuals usually become symptomatic in the second decade of life; some cases present earlier in childhood, whereas others remain asymptomatic into late adult life. Clinically, CMT2 is for the most part indistinguishable from CMT1. NCS are helpful in this regard; in contrast to CMT1, the velocities are normal or only slightly slowed. The most common cause of CMT2 is a mutation in the gene for mitofusin 2 (MFN2), which accounts for one-third of CMT2 cases overall. MFN2 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where it regulates the mitochondrial network architecture by fusion of mitochondria. The other genes associated with CMT2 are much less common.

CMTDI In dominant-intermediate CMTs (CMTDIs), the NCVs are faster than usually seen in CMT1 (e.g., >38 m/s) but slower than in CMT2.

CMT3 CMT3 was originally described by Dejerine and Sottas as a hereditary demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy presenting in infancy or early childhood. Affected children are severely weak. Motor NCVs are markedly slowed, typically 5–10 m/s or less. Most cases of CMT3 are caused by point mutations in the genes for PMP-22, MPZ, or ERG-2, which are also the genes responsible for CMT1.

CMT4 CMT4 is extremely rare and is characterized by a severe, childhood-onset sensorimotor polyneuropathy that is usually inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Electrophysiologic and histologic evaluations can show demyelinating or axonal features. CMT4 is genetically heterogenic (Table 459-4).

CMT1X CMT1X is an X-linked dominant disorder with clinical features similar to CMT1 and CMT2, except that the neuropathy is much more severe in men than in women. CMT1X accounts for approximately 10–15% of CMT overall. Men usually present in the first two decades of life with atrophy and weakness of the distal arms and legs, areflexia, pes cavus, and hammertoes. Obligate women carriers are frequently asymptomatic, but can develop signs and symptoms. Onset in women is usually after the second decade of life, and the neuropathy is milder in severity.

NCS reveal features of both demyelination and axonal degeneration that are more severe in men compared to women. In men, motor NCVs in the arms and legs are moderately slowed (in the low to mid 30-m/s range). About 50% of men with CMT1X have motor NCVs between 15 and 35 m/s with about 80% of these falling between 25 and 35 m/s (intermediate slowing). In contrast, about 80% of women with CMT1X have NCVs in the normal range and 20% have NCVs in the intermediate range. CMT1X is caused by mutations in the connexin 32 gene. Connexins are gap junction structural proteins that are important in cell-to-cell communication.

Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP) HNPP is an autosomal dominant disorder related to CMT1A. Although CMT1A is usually associated with a 1.5-Mb duplication in chromosome 17p11.2 that results in an extra copy of PMP-22 gene, HNPP is caused by inheritance of the chromosome with the corresponding 1.5-Mb deletion of this segment, and thus affected individuals have only one copy of the PMP-22 gene. Patients usually manifest in the second or third decade of life with painless numbness and weakness in the distribution of single peripheral nerves, although multiple mononeuropathies can occur. Symptomatic mononeuropathy or multiple mononeuropathies are often precipitated by trivial compression of nerve(s) as can occur with wearing a backpack, leaning on the elbows, or crossing one’s legs for even a short period of time. These pressure-related mononeuropathies may take weeks or months to resolve. In addition, some affected individuals manifest with a progressive or relapsing, generalized and symmetric, sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy that resembles CMT.

Hereditary Neuralgic Amyotrophy (HNA) HNA is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by recurrent attacks of pain, weakness, and sensory loss in the distribution of the brachial plexus often beginning in childhood. These attacks are similar to those seen with idiopathic brachial plexitis (see below). Attacks may occur in the postpartum period, following surgery, or at other times of stress. Most patients recover over several weeks or months. Slightly dysmorphic features, including hypotelorism, epicanthal folds, cleft palate, syndactyly, micrognathia, and facial asymmetry, are evident in some individuals. EDx demonstrate an axonal process. HNA is caused by mutations in septin 9 (SEPT9). Septins may be important in formation of the neuronal cytoskeleton and have a role in cell division, but the mechanism of causing HNA is unclear.

Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy (HSAN) The HSANs are a very rare group of hereditary neuropathies in which sensory and autonomic dysfunction predominates over muscle weakness, unlike CMT, in which motor findings are most prominent (Table 459-4). Nevertheless, affected individuals can develop motor weakness and there can be overlap with CMT. There are no medical therapies available to treat these neuropathies, other than prevention and treatment of mutilating skin and bone lesions.

Of the HSANs, only HSAN1 typically presents in adults. HSAN1 is the most common of the HSANs and is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Affected individuals with HSAN1 usually manifest in the second through fourth decades of life. HSAN1 is associated with the degeneration of small myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers leading to severe loss of pain and temperature sensation, deep dermal ulcerations, recurrent osteomyelitis, Charcot joints, bone loss, gross foot and hand deformities, and amputated digits. Although most people with HSAN1 do not complain of numbness, they often describe burning, aching, or lancinating pains. Autonomic neuropathy is not a prominent feature, but bladder dysfunction and reduced sweating in the feet may occur. HSAN1A, which is most common, is caused by mutations in the serine palmitoyltransferase long-chain base 1 (SPTLC1) gene.

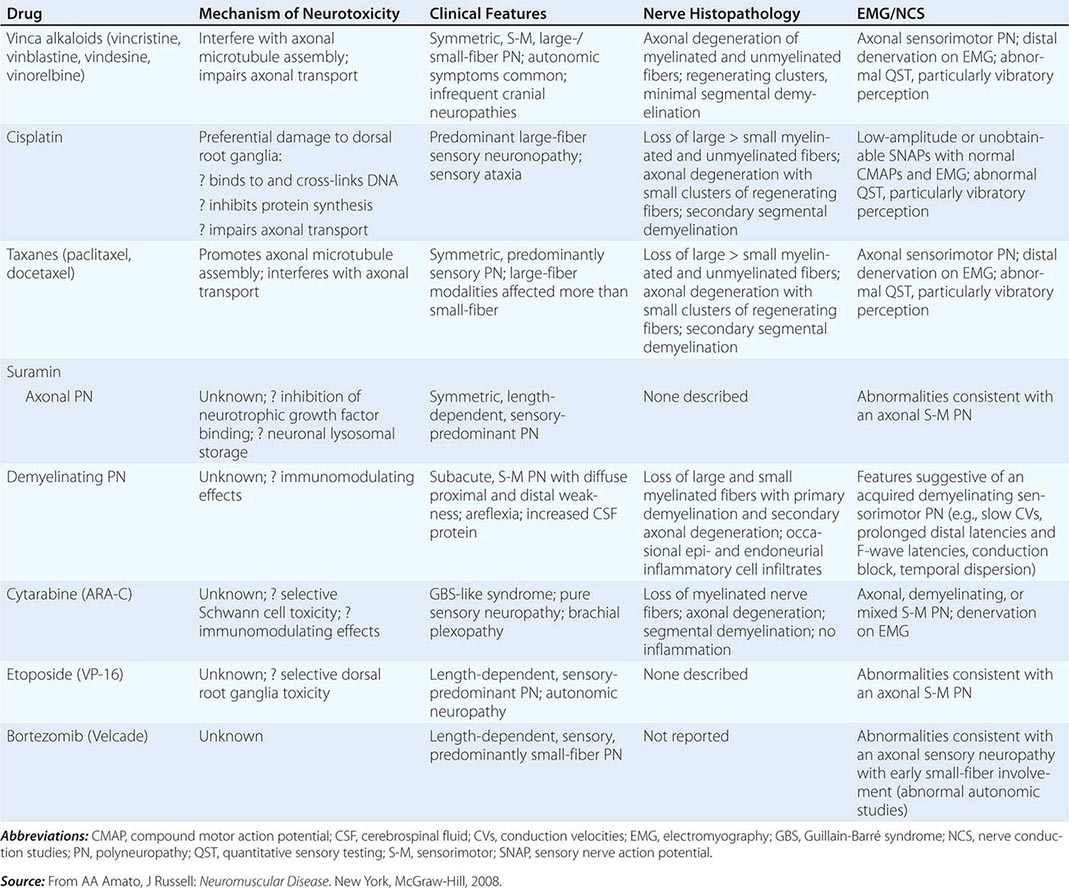

OTHER HEREDITARY NEUROPATHIES (TABLE 459-5)

|

RARE HEREDITARY NEUROPATHIES |

FABRY’S DISEASE

Fabry’s disease (angiokeratoma corporis diffusum) is an X-linked dominant disorder. Although men are more commonly and severely affected, women can also show severe signs of the disease. Angiokeratomas are reddish-purple maculopapular lesions that are usually found around the umbilicus, scrotum, inguinal region, and perineum. Burning or lancinating pain in the hands and feet often develops in males in late childhood or early adult life. However, the neuropathy is usually overshadowed by complications arising from the associated premature atherosclerosis (e.g., hypertension, renal failure, cardiac disease, and stroke) that often lead to death by the fifth decade of life. Some patients also manifest primarily with a dilated cardiomyopathy.

Fabry’s disease is caused by mutations in the a-galactosidase gene that leads to the accumulation of ceramide trihexoside in nerves and blood vessels. A decrease in a-galactosidase activity is evident in leukocytes and cultured fibroblasts. Glycolipid granules may be appreciated in ganglion cells of the peripheral and sympathetic nervous systems and in perineurial cells. Enzyme replacement therapy with a-galactosidase B can improve the neuropathy if patients are treated early, before irreversible nerve fiber loss.

ADRENOLEUKODYSTROPHY/ADRENOMYELONEUROPATHY

Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) and adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN) are allelic X-linked dominant disorders caused by mutations in the peroxisomal transmembrane adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene. Patients with ALD manifest with central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities. However, 30% with mutations in this gene present with the AMN phenotype that typically manifests in the third to fifth decade of life with mild to moderate peripheral neuropathy combined with progressive spastic paraplegia (Chap. 456). Rare patients present with an adult-onset spinocerebellar ataxia or only with adrenal insufficiency.

EDx is suggestive of a primary axonopathy with secondary demyelination. Nerve biopsies demonstrate a loss of myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers with lamellar inclusions in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells. Very long chain fatty acid (VLCFA) levels (C24, C25, and C26) are increased in the urine. Laboratory evidence of adrenal insufficiency is evident in approximately two-thirds of patients. The diagnosis can be confirmed by genetic testing.

Adrenal insufficiency is managed by replacement therapy; however, there is no proven effective therapy for the neurologic manifestations of ALD/AMN. Diets low in VLCFAs and supplemented with Lorenzo’s oil (erucic and oleic acids) reduce the levels of VLCFAs and increase the levels of C22 in serum, fibroblasts, and liver; however, several large, open-label trials of Lorenzo’s oil failed to demonstrate efficacy.

REFSUM’S DISEASE

Refsum’s disease can manifest in infancy to early adulthood with the classic tetrad of (1) peripheral neuropathy, (2) retinitis pigmentosa, (3) cerebellar ataxia, and (4) elevated CSF protein concentration. Most affected individuals develop progressive distal sensory loss and weakness in the legs leading to footdrop by their 20s. Subsequently, the proximal leg and arm muscles may become weak. Patients may also develop sensorineural hearing loss, cardiac conduction abnormalities, ichthyosis, and anosmia.

Serum phytanic acid levels are elevated. Sensory and motor NCS reveal reduced amplitudes, prolonged latencies, and slowed conduction velocities. Nerve biopsy demonstrates a loss of myelinated nerve fibers, with remaining axons often thinly myelinated and associated with onion bulb formation.

Refsum disease is genetically heterogeneous but autosomal recessive in nature. Classical Refsum disease with childhood or early adult onset is caused by mutations in the gene that encodes for phytanoyl-CoA α-hydroxylase (PAHX). Less commonly, mutations in the gene encoding peroxin 7 receptor protein (PRX7) are responsible. These mutations lead to the accumulation of phytanic acid in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Refsum’s disease is treated by removing phytanic precursors (phytols: fish oils, dairy products, and ruminant fats) from the diet.

TANGIER DISEASE

Tangier disease is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that can present as (1) asymmetric multiple mononeuropathies, (2) a slowly progressive symmetric polyneuropathy predominantly in the legs, or (3) a pseudo-syringomyelia pattern with dissociated sensory loss (i.e., abnormal pain/temperature perception but preserved position/vibration in the arms [Chap. 456]). The tonsils may appear swollen and yellowish-orange in color, and there may also be splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy.

Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (ABC1) gene, which leads to markedly reduced levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, whereas triacylglycerol levels are increased. Nerve biopsies reveal axonal degeneration with demyelination and remyelination. Electron microscopy demonstrates abnormal accumulation of lipid in Schwann cells, particularly those encompassing umyelinated and small myelinated nerves. There is no specific treatment.

PORPHYRIA

Porphyria is a group of inherited disorders caused by defects in heme biosynthesis (Chap. 430). Three forms of porphyria are associated with peripheral neuropathy: acute intermittent porphyria (AIP), hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and variegate porphyria (VP). The acute neurologic manifestations are similar in each, with the exception that a photosensitive rash is seen with HCP and VP but not in AIP. Attacks of porphyria can be precipitated by certain drugs (usually those metabolized by the P450 system), hormonal changes (e.g., pregnancy, menstrual cycle), and dietary restrictions.

An acute attack of porphyria may begin with sharp abdominal pain. Subsequently, patients may develop agitation, hallucinations, or seizures. Several days later, back and extremity pain followed by weakness ensues, mimicking GBS. Weakness can involve the arms or the legs and can be asymmetric, proximal, or distal in distribution, as well as affecting the face and bulbar musculature. Dysautonomia and signs of sympathetic overactivity are common (e.g., pupillary dilation, tachycardia, and hypertension). Constipation, urinary retention, and incontinence can also be seen.

The CSF protein is typically normal or mildly elevated. Liver function tests and hematologic parameters are usually normal. Some patients are hyponatremic due to inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (Chap. 401e). The urine may appear brownish in color secondary to the high concentration of porphyrin metabolites. Accumulation of intermediary precursors of heme (i.e., d-aminolevulinic acid, porphobilinogen, uroporphobilinogen, coproporphyrinogen, and protoporphyrinogen) is found in urine. Specific enzyme activities can also be measured in erythrocytes and leukocytes. The primary abnormalities on EDx are marked reductions in compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitudes and signs of active axonal degeneration on needle EMG.

The porphyrias are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. AIP is associated with porphobilinogen deaminase deficiency, HCP is caused by defects in coproporphyrin oxidase, and VP is associated with protoporphyrinogen oxidase deficiency. The pathogenesis of the neuropathy is not completely understood. Treatment with glucose and hematin may reduce the accumulation of heme precursors. Intravenous glucose is started at a rate of 10–20 g/h. If there is no improvement within 24 h, intravenous hematin 2–5 mg/kg per day for 3–14 days should be given.

FAMILIAL AMYLOID POLYNEUROPATHY

Familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) is phenotypically and genetically heterogeneous and is caused by mutations in the genes for transthyretin (TTR), apolipoprotein A1, or gelsolin (Chap. 137). The majority of patients with FAP have mutations in the TTR gene. Amyloid deposition may be evident in abdominal fat pad, rectal, or nerve biopsies. The clinical features, histopathology, and EDx reveal abnormalities consistent with a generalized or multifocal, predominantly axonal but occasionally demyelinating, sensorimotor polyneuropathy.

Patients with TTR-related FAP usually develop insidious onset of numbness and painful paresthesias in the distal lower limbs in the third to fourth decade of life, although some patients develop the disorder later in life. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is common. Autonomic involvement can be severe, leading to postural hypotension, constipation or persistent diarrhea, erectile dysfunction, and impaired sweating. Amyloid deposition also occurs in the heart, kidneys, liver, and corneas. Patients usually die 10–15 years after the onset of symptoms from cardiac failure or complications from malnutrition. Because the liver produces much of the body’s TTR, liver transplantation has been used to treat FAP related to TTR mutations. Serum TTR levels decrease after transplantation, and improvement in clinical and EDx features has been reported.

Patients with apolipoprotein A1-related FAP (Van Allen type) usually present in the fourth decade with numbness and painful dysesthesias in the distal limbs. Gradually, the symptoms progress, leading to proximal and distal weakness and atrophy. Although autonomic neuropathy is not severe, some patients develop diarrhea, constipation, or gastroparesis. Most patients die from systemic complications of amyloidosis (e.g., renal failure) 12–15 years after the onset of the neuropathy.

Gelsolin-related amyloidosis (Finnish type) is characterized by the combination of lattice corneal dystrophy and multiple cranial neuropathies that usually begin in the third decade of life. Over time, a mild generalized sensorimotor polyneuropathy develops. Autonomic dysfunction does not occur.

ACQUIRED NEUROPATHIES

PRIMARY OR AL AMYLOIDOSIS (SEE CHAP. 137)

Besides FAP, amyloidosis can also be acquired. In primary or AL amyloidosis, the abnormal protein deposition is composed of immunoglobulin light chains. AL amyloidosis occurs in the setting of multiple myeloma, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, lymphoma, other plasmacytomas, or lymphoproliferative disorders, or without any other identifiable disease.

Approximately 30% of patients with AL primary amyloidosis present with a polyneuropathy, most typically painful dysesthesias and burning sensations in the feet. However, the trunk can be involved, and some patients manifest with a mononeuropathy multiplex pattern. CTS occurs in 25% of patients and may be the initial manifestation. The neuropathy is slowly progressive, and eventually weakness develops along with large-fiber sensory loss. Most patients develop autonomic involvement with postural hypertension, syncope, bowel and bladder incontinence, constipation, impotence, and impaired sweating. Patients generally die from their systemic illness (renal failure, cardiac disease).

The monoclonal protein may be composed of IgG, IgA, IgM, or only free light chain. Lambda (λ) is more common than κ light chain (>2:1) in AL amyloidosis. The CSF protein is often increased (with normal cell count), and thus the neuropathy may be mistaken for CIDP (Chap. 460). Nerve biopsies reveal axonal degeneration and amyloid deposition in either a globular or diffuse pattern infiltrating the perineurial, epineurial, and endoneurial connected tissue and in blood vessel walls.

The median survival of patients with primary amyloidosis is less than 2 years, with death usually from progressive congestive heart failure or renal failure. Chemotherapy with melphalan, prednisone, and colchicine, to reduce the concentration of monoclonal proteins, and autologous stem cell transplantation may prolong survival, but whether the neuropathy improves is controversial.

DIABETIC NEUROPATHY

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the most common cause of peripheral neuropathy in developed countries. DM is associated with several types of polyneuropathy: distal symmetric sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, diabetic neuropathic cachexia, polyradiculoneuropathies, cranial neuropathies, and other mononeuropathies. Risk factors for the development of neuropathy include long-standing, poorly controlled DM and the presence of retinopathy and nephropathy.

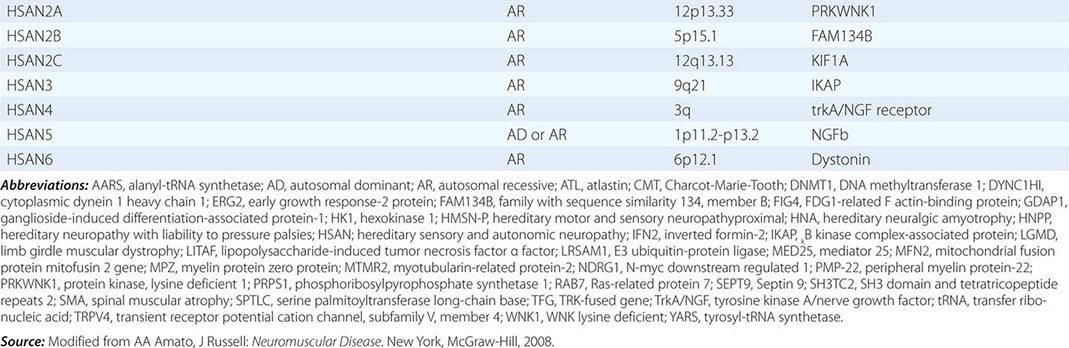

Diabetic Distal Symmetric Sensory and Sensorimotor Polyneuropathy (DSPN) DSPN is the most common form of diabetic neuropathy and manifests as sensory loss beginning in the toes that gradually progresses over time up the legs and into the fingers and arms. When severe, a patient may develop sensory loss in the trunk (chest and abdomen), initially in the midline anteriorly and later extending laterally. Tingling, burning, deep aching pains may also be apparent. NCS usually show reduced amplitudes and mild to moderate slowing of conduction velocities (CVs). Nerve biopsy reveals axonal degeneration, endothelial hyperplasia, and, occasionally, perivascular inflammation. Tight control of glucose can reduce the risk of developing neuropathy or improve the underlying neuropathy. A variety of medications have been used with variable success to treat painful symptoms associated with DSPN, including antiepileptic medications, antidepressants, sodium channel blockers, and other analgesics (Table 459-6).

|

TREATMENT OF PAINFUL SENSORY NEUROPATHIES |

Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy Autonomic neuropathy is typically seen in combination with DSPN. The autonomic neuropathy can manifest as abnormal sweating, dysfunctional thermoregulation, dry eyes and mouth, pupillary abnormalities, cardiac arrhythmias, postural hypotension, GI abnormalities (e.g., gastroparesis, postprandial bloating, chronic diarrhea or constipation), and genitourinary dysfunction (e.g., impotence, retrograde ejaculation, incontinence). Tests of autonomic function are generally abnormal, including sympathetic skin responses and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex testing. Sensory and motor NCS generally demonstrate features described above with DSPN.

Diabetic Radiculoplexus Neuropathy (Diabetic Amyotrophy or Bruns-Garland Syndrome) Diabetic radiculoplexus neuropathy is the presenting manifestation of DM in approximately one-third of patients. Typically, patients present with severe pain in the low back, hip, and thigh in one leg. Rarely, the diabetic polyradiculoneuropathy begins in both legs at the same time. Atrophy and weakness of proximal and distal muscles in the affected leg become apparent within a few days or weeks. The neuropathy is often accompanied or heralded by severe weight loss. Weakness usually progresses over several weeks or months, but can continue to progress for 18 months or more. Subsequently, there is slow recovery but many are left with residual weakness, sensory loss, and pain. In contrast to the more typical lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, some patients develop thoracic radiculopathy or, even less commonly, a cervical polyradiculoneuropathy. CSF protein is usually elevated, while the cell count is normal. ESR is often increased. EDx reveals evidence of active denervation in affected proximal and distal muscles in the affected limbs and in paraspinal muscles. Nerve biopsies may demonstrate axonal degeneration along with perivascular inflammation. Patients with severe pain are sometimes treated in the acute period with glucocorticoids, although a randomized controlled trial has yet to be performed, and the natural history of this neuropathy is gradual improvement.

Diabetic Mononeuropathies or Multiple Mononeuropathies The most common mononeuropathies are median neuropathy at the wrist and ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, but peroneal neuropathy at the fibular head, and sciatic, lateral femoral, cutaneous, or cranial neuropathies also occur. In regard to cranial mononeuropathies, seventh nerve palsies are relatively common but may have other, nondiabetic etiologies. In diabetics, a third nerve palsy is most common, followed by sixth nerve, and, less frequently, fourth nerve palsies. Diabetic third nerve palsies are characteristically pupil-sparing (Chap. 39).

HYPOTHYROIDISM

Hypothyroidism is more commonly associated with a proximal myopathy, but some patients develop a neuropathy, most typically CTS. Rarely, a generalized sensory polyneuropathy characterized by painful paresthesias and numbness in both the legs and hands can occur. Treatment is correction of the hypothyroidism.

SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME

Sjögren’s syndrome, characterized by the sicca complex of xerophthalmia, xerostomia, and dryness of other mucous membranes, can be complicated by neuropathy (Chap. 383). Most common is a length-dependent axonal sensorimotor neuropathy characterized mainly by sensory loss in the distal extremities. A pure small-fiber neuropathy or a cranial neuropathy, particularly involving the trigeminal nerve, can also be seen. Sjögren’s syndrome is also associated with sensory neuronopathy/ganglionopathy. Patients with sensory ganglionopathies develop progressive numbness and tingling of the limbs, trunk, and face in a non-length-dependent manner such that symptoms can involve the face or arms more than the legs. The onset can be acute or insidious. Sensory examination demonstrates severe vibratory and proprioceptive loss leading to sensory ataxia.

Patients with neuropathy due to Sjögren’s syndrome may have ANAs, SS-A/Ro, and SS-B/La antibodies in the serum, but most do not. NCS demonstrate reduced amplitudes of sensory studies in the affected limbs. Nerve biopsy demonstrates axonal degeneration. Nonspecific perivascular inflammation may be present, but only rarely is there necrotizing vasculitis. There is no specific treatment for neuropathies related to Sjögren’s syndrome. When vasculitis is suspected, immunosuppressive agents may be beneficial. Occasionally, the sensory neuronopathy/ganglionopathy stabilizes or improves with immunotherapy, such as IVIg.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Peripheral neuropathy occurs in at least 50% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and may be vasculitic in nature (Chap. 380). Vasculitic neuropathy can present with a mononeuropathy multiplex, a generalized symmetric pattern of involvement, or a combination of these patterns (Chap. 385). Neuropathies may also be due to drugs used to treat the RA (e.g., tumor necrosis blockers, leflunomide). Nerve biopsy often reveals thickening of the epineurial and endoneurial blood vessels as well as perivascular inflammation or vasculitis, with transmural inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls. The neuropathy often is responsive to immunomodulating therapies.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (SLE)

Between 2 and 27% of individuals with SLE develop a peripheral neuropathy (Chap. 378). Affected patients typically present with a slowly progressive sensory loss beginning in the feet. Some patients develop burning pain and paresthesias with normal reflexes, and NCS suggest a pure small-fiber neuropathy. Less common are multiple mononeuropathies presumably secondary to necrotizing vasculitis. Rarely, a generalized sensorimotor polyneuropathy meeting clinical, laboratory, electrophysiologic, and histologic criteria for either GBS or CIDP may occur. Immunosuppressive therapy is beneficial in SLE patients with neuropathy due to vasculitis. Immunosuppressive agents are less likely to be effective in patients with a generalized sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy without evidence of vasculitis. Patients with a GBS or CIDP-like neuropathy should be treated accordingly (Chap. 385).

SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS (SCLERODERMA)

A distal symmetric, mainly sensory, polyneuropathy complicates 5–67% of scleroderma cases (Chap. 382). Cranial mononeuropathies can also develop, most commonly of the trigeminal nerve, producing numbness and dysesthesias in the face. Multiple mononeuropathies also occur. The EDx and histologic features of nerve biopsy are those of an axonal sensory greater than motor polyneuropathy.

MIXED CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE (MCTD)

A mild distal axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy occurs in approximately 10% of patients with MCTD.

SARCOIDOSIS

The peripheral or central nervous system is involved in about 5% of patients with sarcoidosis (Chap. 390). The most common cranial nerve involved is the seventh nerve, which can be affected bilaterally. Some patients develop radiculopathy or polyradiculopathy. With a generalized root involvement, the clinical presentation can mimic GBS or CIDP. Patients can also present with multiple mononeuropathies or a generalized, slowly progressive, sensory greater than motor polyneuropathy. Some have features of a pure small-fiber neuropathy. EDx reveals an axonal neuropathy. Nerve biopsy can reveal noncaseating granulomas infiltrating the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium along with lymphocytic necrotizing angiitis. Neurosarcoidosis may respond to treatment with glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive agents.

HYPEREOSINOPHILIC SYNDROME

Hypereosinophilic syndrome is characterized by eosinophilia associated with various skin, cardiac, hematologic, and neurologic abnormalities. A generalized peripheral neuropathy or a mononeuropathy multiplex occurs in 6–14% of patients.

CELIAC DISEASE (GLUTEN-INDUCED ENTEROPATHY OR NONTROPICAL SPRUE)

Neurologic complications, particularly ataxia and peripheral neuropathy, are estimated to occur in 10% of patients with celiac disease (Chap. 349). A generalized sensorimotor polyneuropathy, pure motor neuropathy, multiple mononeuropathies, autonomic neuropathy, small-fiber neuropathy, and neuromyotonia have all been reported in association with celiac disease or antigliadin/antiendomysial antibodies. Nerve biopsy may reveal a loss of large myelinated fibers. The neuropathy may be secondary to malabsorption of vitamins B12 and E. However, some patients have no appreciable vitamin deficiencies. The pathogenic basis for the neuropathy in these patients is unclear but may be autoimmune in etiology. The neuropathy does not appear to respond to a gluten-free diet. In patients with vitamin B12 or vitamin E deficiency, replacement therapy may improve or stabilize the neuropathy.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease may be complicated by GBS, CIDP, generalized axonal sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathy, small-fiber neuropathy, or mononeuropathy (Chap. 351). These neuropathies may be autoimmune, nutritional (e.g., vitamin B12 deficiency), treatment related (e.g., metronidazole), or idiopathic in nature. An acute neuropathy with demyelination resembling GBS, CIDP, or multifocal motor neuropathy may occur in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor α blockers.

UREMIC NEUROPATHY

Approximately 60% of patients with renal failure develop a polyneuropathy characterized by length-dependent numbness, tingling, allodynia, and mild distal weakness. Rarely, a rapidly progressive weakness and sensory loss very similar to GBS can occur that improves with an increase in the intensity of renal dialysis or with transplantation. Mononeuropathies can also occur, the most common of which is CTS. Ischemic monomelic neuropathy (see below) can complicate arteriovenous shunts created in the arm for dialysis. EDx in uremic patients reveals features of a length-dependent, primarily axonal, sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Sural nerve biopsies demonstrate a loss of nerve fibers (particularly large myelinated nerve fibers), active axonal degeneration, and segmental and paranodal demyelination. The sensorimotor polyneuropathy can be stabilized by hemodialysis and improved with successful renal transplantation.

CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

A generalized sensorimotor neuropathy characterized by numbness, tingling, and minor weakness in the distal aspects of primarily the lower limbs commonly occurs in patients with chronic liver failure. EDx studies are consistent with a sensory greater than motor axonopathy. Sural nerve biopsy reveals both segmental demyelination and axonal loss. It is not known if hepatic failure in isolation can cause peripheral neuropathy, as the majority of patients have liver disease secondary to other disorders, such as alcoholism or viral hepatitis, which can also cause neuropathy.

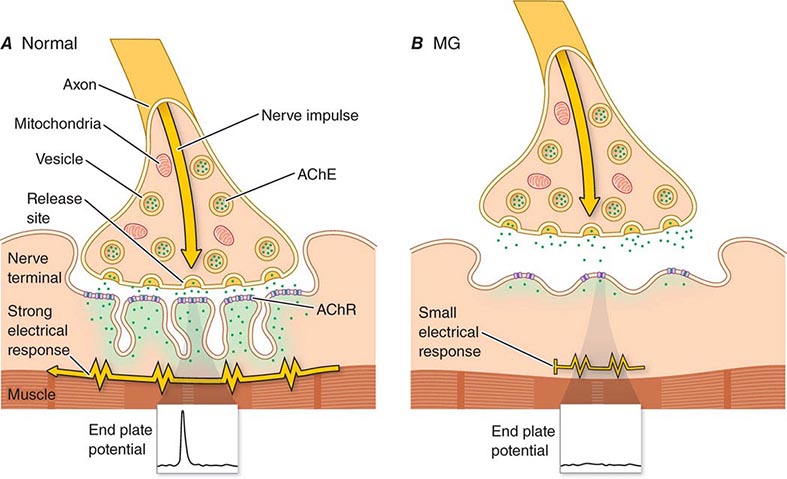

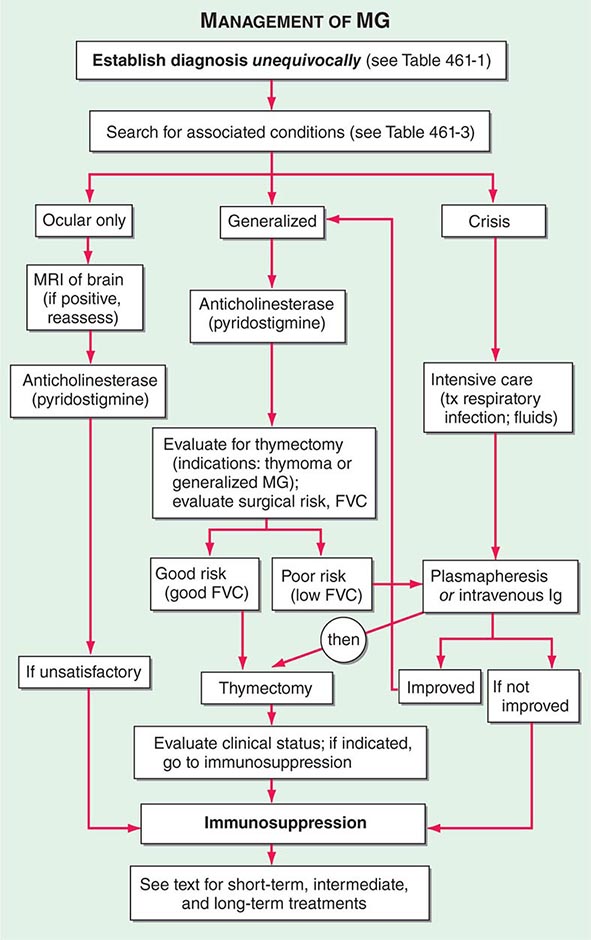

CRITICAL ILLNESS POLYNEUROPATHY

The most common causes of acute generalized weakness leading to admission to a medical intensive care unit (ICU) are GBS and myasthenia gravis (Chap. 461). However, weakness developing in critically ill patients while in the ICU is usually caused by critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) or critical illness myopathy (CIM) or, much less commonly, by prolonged neuromuscular blockade. From a clinical and EDx standpoint, it can be quite difficult to distinguish these disorders. Most specialists suggest that CIM is more common. Both CIM and CIP develop as a complication of sepsis and multiple organ failure. They usually present as an inability to wean a patient from a ventilator. A coexisting encephalopathy may limit the neurologic exam, in particular the sensory examination. Muscle stretch reflexes are absent or reduced.

Serum creatine kinase (CK) is usually normal; an elevated serum CK would point to CIM as opposed to CIP. NCS reveal absent or markedly reduced amplitudes of motor and sensory studies in CIP, whereas sensory studies are relatively preserved in CIM. Needle EMG usually reveals profuse positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials, and it is not unusual in patients with severe weakness to be unable to recruit motor unit action potentials. The pathogenic basis of CIP is not known. Perhaps circulating toxins and metabolic abnormalities associated with sepsis and multiorgan failure impair axonal transport or mitochondrial function, leading to axonal degeneration.

LEPROSY (HANSEN’S DISEASE)

![]() Leprosy, caused by the acid-fast bacteria Mycobacterium leprae, is the most common cause of peripheral neuropathy in Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America (Chap. 203). Clinical manifestations range from tuberculoid leprosy at one end to lepromatous leprosy at the other end of the spectrum, with borderline leprosy in between. Neuropathies are most common in patients with borderline leprosy. Superficial cutaneous nerves of the ears and distal limbs are commonly affected. Mononeuropathies, multiple mononeuropathies, or a slowly progressive symmetric sensorimotor polyneuropathy may develop. Sensory NCS are usually absent in the lower limb and are reduced in amplitude in the arms. Motor NCS may demonstrate reduced amplitudes in affected nerves but occasionally can reveal demyelinating features. Leprosy is usually diagnosed by skin lesion biopsy. Nerve biopsy can also be diagnostic, particularly when there are no apparent skin lesions. The tuberculoid form is characterized by granulomas, and bacilli are not seen. In contrast, with lepromatous leprosy, large numbers of infiltrating bacilli, TH2 lymphocytes, and organism-laden, foamy macrophages with minimal granulomatous infiltration are evident. The bacilli are best appreciated using the Fite stain, where they can be seen as red-staining rods often in clusters free in the endoneurium, within macrophages, or within Schwann cells.

Leprosy, caused by the acid-fast bacteria Mycobacterium leprae, is the most common cause of peripheral neuropathy in Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America (Chap. 203). Clinical manifestations range from tuberculoid leprosy at one end to lepromatous leprosy at the other end of the spectrum, with borderline leprosy in between. Neuropathies are most common in patients with borderline leprosy. Superficial cutaneous nerves of the ears and distal limbs are commonly affected. Mononeuropathies, multiple mononeuropathies, or a slowly progressive symmetric sensorimotor polyneuropathy may develop. Sensory NCS are usually absent in the lower limb and are reduced in amplitude in the arms. Motor NCS may demonstrate reduced amplitudes in affected nerves but occasionally can reveal demyelinating features. Leprosy is usually diagnosed by skin lesion biopsy. Nerve biopsy can also be diagnostic, particularly when there are no apparent skin lesions. The tuberculoid form is characterized by granulomas, and bacilli are not seen. In contrast, with lepromatous leprosy, large numbers of infiltrating bacilli, TH2 lymphocytes, and organism-laden, foamy macrophages with minimal granulomatous infiltration are evident. The bacilli are best appreciated using the Fite stain, where they can be seen as red-staining rods often in clusters free in the endoneurium, within macrophages, or within Schwann cells.

Patients are generally treated with multiple drugs: dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Other medications that are used include thalidomide, pefloxacin, ofloxacin, sparfloxacin, minocycline, and clarithromycin. Patients are generally treated for 2 years. Treatment is sometimes complicated by the so-called reversal reaction, particularly in borderline leprosy. The reversal reaction can occur at any time during treatment and develops because of a shift to the tuberculoid end of the spectrum, with an increase in cellular immunity during treatment. The cellular response is upregulated as evidenced by an increased release of tumor necrosis factor α, interferon γ, and interleukin 2, with new granuloma formation. This can result in an exacerbation of the rash and the neuropathy as well as in appearance of new lesions. High-dose glucocorticoids blunt this adverse reaction and may be used prophylactically at treatment onset in high-risk patients. Erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) is also treated with glucocorticoids or thalidomide.

LYME DISEASE

Lyme disease is caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete usually transmitted by the deer tick Ixodes dammini (Chap. 210). Neurologic complications may develop during the second and third stages of infection. Facial neuropathy is most common and is bilateral in about half of cases, which is rare for idiopathic Bell’s palsy. Involvement of nerves is frequently asymmetric. Some patients present with a polyradiculoneuropathy or multiple mononeuropathies. EDx is suggestive of a primary axonopathy. Nerve biopsies can reveal axonal degeneration with perivascular inflammation. Treatment is with antibiotics (Chap. 210).

DIPHTHERITIC NEUROPATHY

Diphtheria is caused by the bacteria Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Chap. 175). Infected individuals present with flulike symptoms of generalized myalgias, headache, fatigue, low-grade fever, and irritability within a week to 10 days of the exposure. About 20–70% of patients develop a peripheral neuropathy caused by a toxin released by the bacteria. Three to 4 weeks after infection, patients may note decreased sensation in their throat and begin to develop dysphagia, dysarthria, hoarseness, and blurred vision due to impaired accommodation. A generalized polyneuropathy may manifest 2 or 3 months following the initial infection, characterized by numbness, paresthesias, and weakness of the arms and legs and occasionally ventilatory failure. CSF protein can be elevated with or without lymphocytic pleocytosis. EDx suggests a diffuse axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Antitoxin and antibiotics should be given within 48 h of symptom onset. Although early treatment reduces the incidence and severity of some complications (i.e., cardiomyopathy), it does not appear to alter the natural history of the associated peripheral neuropathy. The neuropathy usually resolves after several months.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV)

HIV infection can result in a variety of neurologic complications, including peripheral neuropathies (Chap. 226). Approximately 20% of HIV-infected individuals develop a neuropathy either as a direct result of the virus itself, other associated viral infections (e.g., CMV), or neurotoxicity secondary to antiviral medications (see below). The major presentations of peripheral neuropathy associated with HIV infection include (1) distal symmetric polyneuropathy, (2) inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (including both GBS and CIDP), (3) multiple mononeuropathies (e.g., vasculitis, CMV-related), (4) polyradiculopathy (usually CMV-related), (5) autonomic neuropathy, and (6) sensory ganglionitis.

HIV-Related Distal Symmetric Polyneuropathy (DSP) DSP is the most common form of peripheral neuropathy associated with HIV infection and usually is seen in patients with AIDS. It is characterized by numbness and painful paresthesias involving the distal extremities. The pathogenic basis for DSP is unknown but is not due to actual infection of the peripheral nerves. The neuropathy may be immune mediated, perhaps caused by the release of cytokines from surrounding inflammatory cells. Vitamin B12 deficiency may contribute in some instances but is not a major cause of most cases of DSP. Some antiretroviral agents (e.g., dideoxycytidine, dideoxyinosine, stavudine) are also neurotoxic and can cause a painful sensory neuropathy.

HIV-Related Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy Both AIDP and CIDP can occur as a complication of HIV infection. AIDP usually develops at the time of seroconversion, whereas CIDP can occur any time in the course of the infection. Clinical and EDx features are indistinguishable from idiopathic AIDP or CIDP (discussed in Chap. 460). In addition to elevated protein levels, lymphocytic pleocytosis is evident in the CSF, a finding that helps distinguish this HIV-associated polyradiculoneuropathy from idiopathic AIDP/CIDP.

HIV-Related Progressive Polyradiculopathy An acute, progressive lumbosacral polyradiculoneuropathy usually secondary to CMV infection can develop in patients with AIDS. Patients present with severe radicular pain, numbness, and weakness in the legs, which is usually asymmetric. CSF is abnormal, demonstrating an increased protein along with reduced glucose concentration and notably a neutrophilic pleocytosis. EDx studies reveal features of active axonal degeneration. The polyradiculoneuropathy may improve with antiviral therapy.

HIV-Related Multiple Mononeuropathies Multiple mononeuropathies can also develop in patients with HIV infection, usually in the context of AIDS. Weakness, numbness, paresthesias, and pain occur in the distribution of affected nerves. Nerve biopsies can reveal axonal degeneration with necrotizing vasculitis or perivascular inflammation. Glucocorticoid treatment is indicated for vasculitis directly due to HIV infection.

HIV-Related Sensory Neuronopathy/Ganglionopathy Dorsal root ganglionitis is a very rare complication of HIV infection, and neuronopathy can be the presenting manifestation. Patients develop sensory ataxia similar to idiopathic sensory neuronopathy/ganglionopathy. NCS reveal reduced amplitudes or absence of sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs).

HERPES VARICELLA-ZOSTER VIRUS

Peripheral neuropathy from herpes varicella-zoster (HVZ) infection results from reactivation of latent virus or from a primary infection (Chap. 217). Two-thirds of infections in adults are characterized by dermal zoster in which severe pain and paresthesias develop in a dermatomal region followed within a week or two by a vesicular rash in the same distribution. Weakness in muscles innervated by roots corresponding to the dermatomal distribution of skin lesions occurs in 5–30% of patients. Approximately 25% of affected patients have continued pain (postherpetic neuralgia [PHN]). A large clinical trial demonstrated that vaccination against zoster reduces the incidence of HVZ among vaccine recipients by 51% and reduces the incidence of PHN by 67%. Treatment of PHN is symptomatic (Table 459-6).

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

CMV can cause an acute lumbosacral polyradiculopathy and multiple mononeuropathies in patients with HIV infection and in other immune deficiency conditions (Chap. 219).

EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS

EBV infection has been associated with GBS, cranial neuropathies, mononeuropathy multiplex, brachial plexopathy, lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy, and sensory neuronopathies (Chap. 218).

HEPATITIS VIRUSES

Hepatitis B and C can cause multiple mononeuropathies related to vasculitis, AIDP, or CIDP (Chap. 362).

NEUROPATHIES ASSOCIATED WITH MALIGNANCY

Patients with malignancy can develop neuropathies due to (1) a direct effect of the cancer by invasion or compression of the nerves, (2) remote or paraneoplastic effect, (3) a toxic effect of treatment, or (4) as a consequence of immune compromise caused by immunosuppressive medications. The most common associated malignancy is lung cancer, but neuropathies also complicate carcinoma of the breast, ovaries, stomach, colon, rectum, and other organs, including the lymphoproliferative system.

PARANEOPLASTIC SENSORY NEURONOPATHY/GANGLIONOPATHY

Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy (PEM/SN) usually complicates small-cell lung carcinoma (Chap. 122). Patients usually present with numbness and paresthesias in the distal extremities that are often asymmetric. The onset can be acute or insidiously progressive. Prominent loss of proprioception leads to sensory ataxia. Weakness can be present, usually secondary to an associated myelitis, motor neuronopathy, or concurrent Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS). Many patients also develop confusion, memory loss, depression, hallucinations or seizures, or cerebellar ataxia. Polyclonal antineuronal antibodies (IgG) directed against a 35- to 40-kDa protein or complex of proteins, the so-called Hu antigen, are found in the sera or CSF in the majority of patients with paraneoplastic PEM/SN. CSF may be normal or may demonstrate mild lymphocytic pleocytosis and elevated protein. PEM/SN is probably the result of antigenic similarity between proteins expressed in the tumor cells and neuronal cells, leading to an immune response directed against both cell types. Treatment of the underlying cancer generally does not affect the course of PEM/SN. However, occasional patients may improve following treatment of the tumor. Unfortunately, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, and immunosuppressive agents have not shown benefit.

NEUROPATHY SECONDARY TO TUMOR INFILTRATION

Malignant cells, in particular leukemia and lymphoma, can infiltrate cranial and peripheral nerves, leading to mononeuropathy, mononeuropathy multiplex, polyradiculopathy, plexopathy, or even a generalized symmetric distal or proximal and distal polyneuropathy. Neuropathy related to tumor infiltration is often painful; it can be the presenting manifestation of the cancer or the heralding symptom of a relapse. The neuropathy may improve with treatment of the underlying leukemia or lymphoma or with glucocorticoids.

NEUROPATHY AS A COMPLICATION OF BONE MARROW TRANSPLANTATION

Neuropathies may develop in patients who undergo bone marrow transplantation (BMT) because of the toxic effects of chemotherapy, radiation, infection, or an autoimmune response directed against the peripheral nerves. Peripheral neuropathy in BMT is often associated with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Chronic GVHD shares many features with a variety of autoimmune disorders, and it is possible that an immune-mediated response directed against peripheral nerves is responsible. Patients with chronic GVHD may develop cranial neuropathies, sensorimotor polyneuropathies, multiple mononeuropathies, and severe generalized peripheral neuropathies resembling AIDP or CIDP. The neuropathy may improve by increasing the intensity of immunosuppressive or immunomodulating therapy and resolution of the GVHD.

LYMPHOMA

Lymphomas may cause neuropathy by infiltration or direct compression of nerves or by a paraneoplastic process. The neuropathy can be purely sensory or motor, but most commonly is sensorimotor. The pattern of involvement may be symmetric, asymmetric, or multifocal, and the course may be acute, gradually progressive, or relapsing and remitting. EDx can be compatible with either an axonal or demyelinating process. CSF may reveal lymphocytic pleocytosis and an elevated protein. Nerve biopsy may demonstrate endoneurial inflammatory cells in both the infiltrative and the paraneoplastic etiologies. A monoclonal population of cells favors lymphomatous invasion. The neuropathy may respond to treatment of the underlying lymphoma or immunomodulating therapies.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Multiple myeloma (MM) usually presents in the fifth to seventh decade of life with fatigue, bone pain, anemia, and hypercalcemia (Chap. 136). Clinical and EDx features of neuropathy occur in as many as 40% of patients. The most common pattern is that of a distal, axonal, sensory, or sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Less frequently, a chronic demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy may develop (see POEMS, Chap. 460). MM can be complicated by amyloid polyneuropathy and should be considered in patients with painful paresthesias, loss of pinprick and temperature discrimination, and autonomic dysfunction (suggestive of a small-fiber neuropathy) and CTS. Expanding plasmacytomas can compress cranial nerves and spinal roots as well. A monoclonal protein, usually composed of γ or μ heavy chains or κ light chains, may be identified in the serum or urine. EDx usually shows reduced amplitudes with normal or only mildly abnormal distal latencies and conduction velocities. A superimposed median neuropathy at the wrist is common. Abdominal fat pad, rectal, or sural nerve biopsy can be performed to look for amyloid deposition. Unfortunately, the treatment of the underlying MM does not usually affect the course of the neuropathy.

NEUROPATHIES ASSOCIATED WITH MONOCLONAL GAMMOPATHY OF UNCERTAIN SIGNIFICANCE (SEE CHAP. 460)

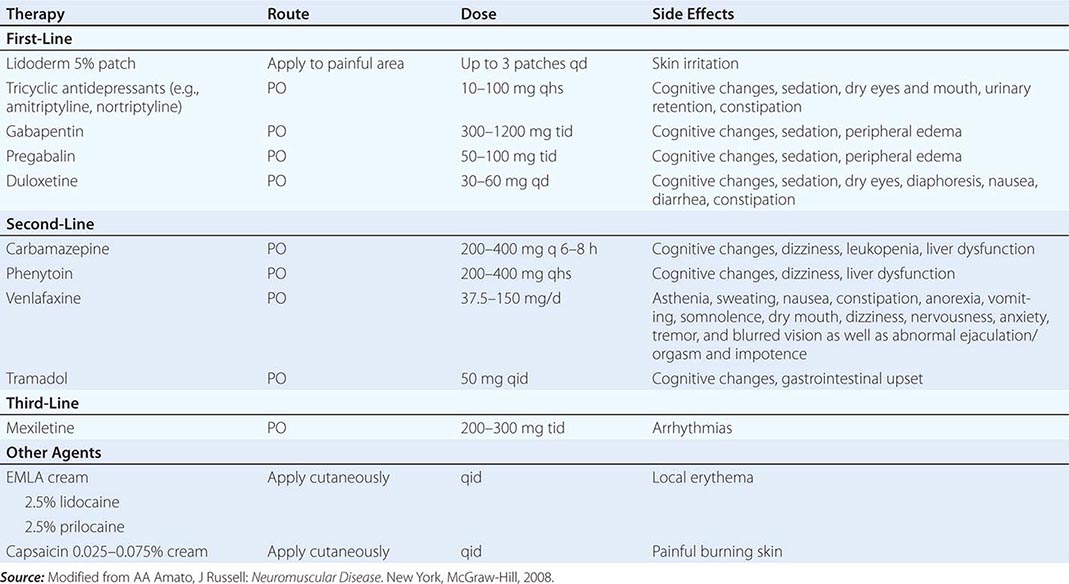

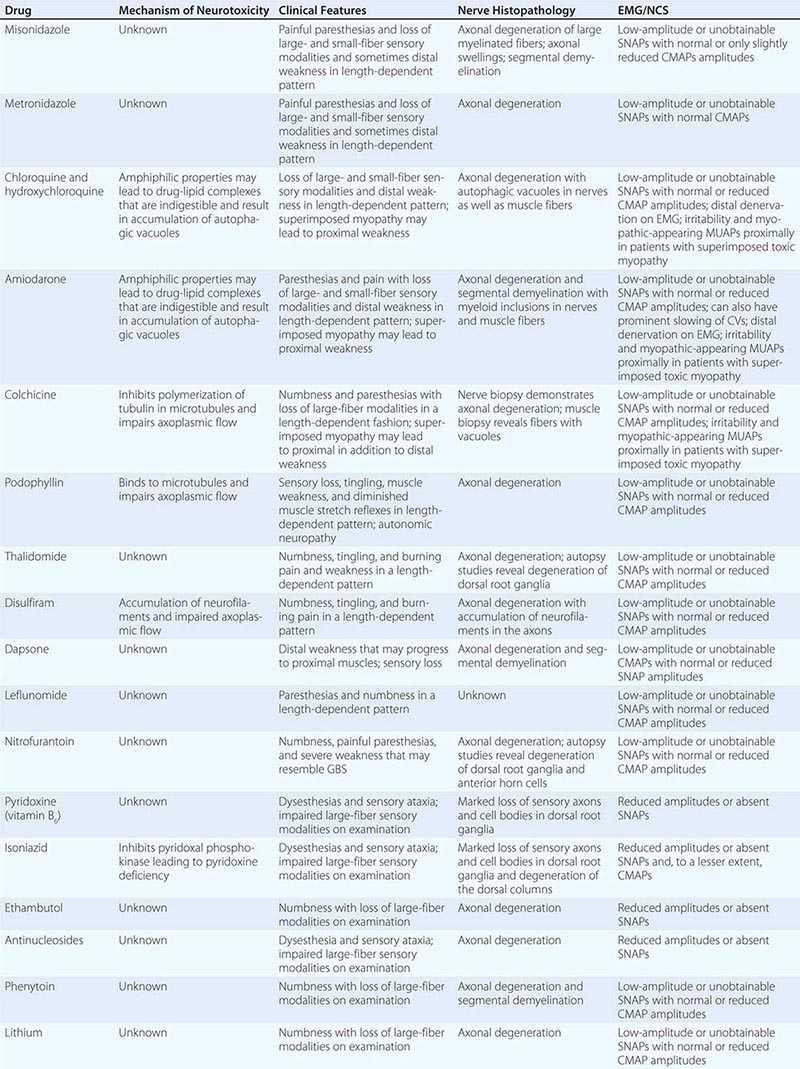

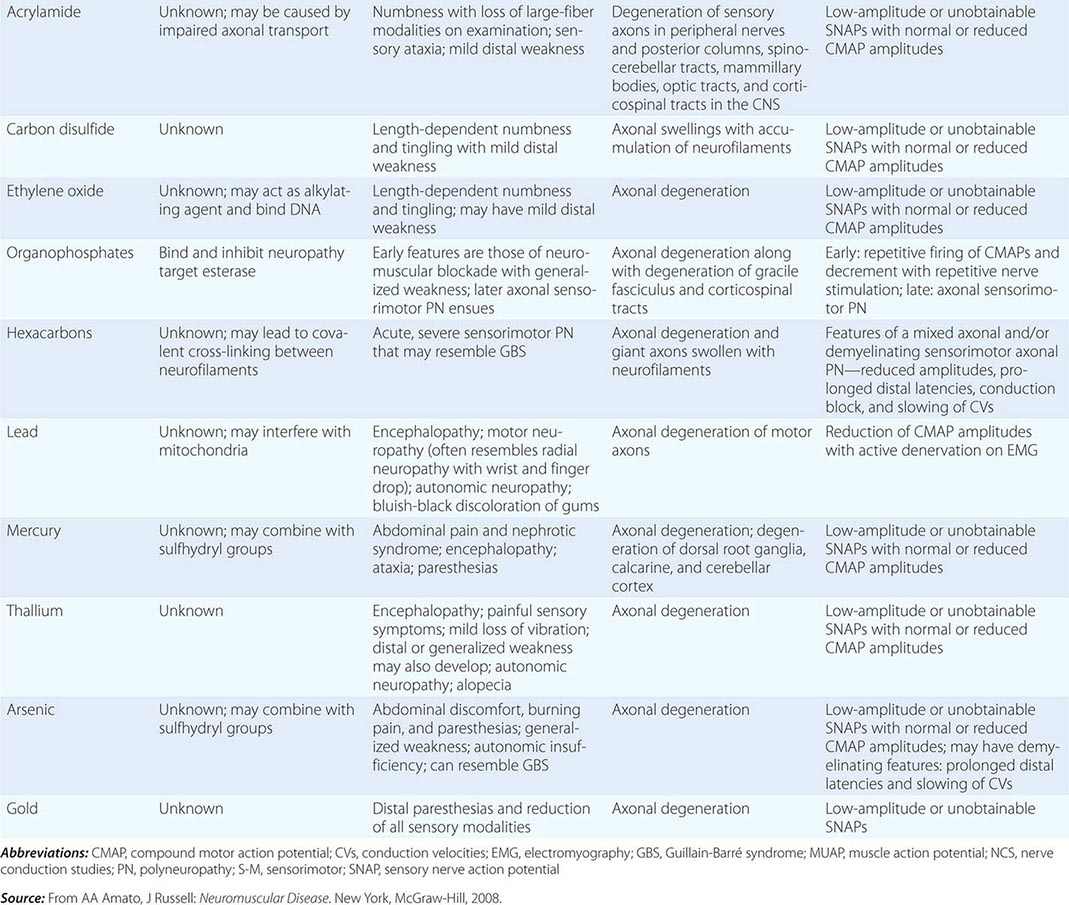

Toxic Neuropathies Secondary to Chemotherapy Many of the commonly used chemotherapy agents can cause a toxic neuropathy (Table 459-7). The mechanisms by which these agents cause toxic neuropathies vary, as does the specific type of neuropathy produced. The risk of developing a toxic neuropathy or more severe neuropathy appears to be greater in patients with a preexisting neuropathy (e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, diabetic neuropathy) and those who also take other potentially neurotoxic drugs (e.g., nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, disulfiram, pyridoxine). Chemotherapeutic agents usually cause a sensory greater than motor length-dependent axonal neuropathy or neuronopathy/ganglionopathy.

|

TOXIC NEUROPATHIES SECONDARY TO CHEMOTHERAPY |

OTHER TOXIC NEUROPATHIES

Neuropathies can develop as complications of toxic effects of various drugs and other environmental exposures (Table 459-8). The more common neuropathies associated with these agents are discussed here.

|

TOXIC NEUROPATHIES |

CHLOROQUINE AND HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine can cause a toxic myopathy characterized by slowly progressive, painless, proximal weakness and atrophy, which is worse in the legs than the arms. In addition, neuropathy can also develop with or without the myopathy leading to sensory loss and distal weakness. The “neuromyopathy” usually appears in patients taking 500 mg daily for a year or more but has been reported with doses as low as 200 mg/d. Serum CK levels are usually elevated due to the superimposed myopathy. NCS reveal mild slowing of motor and sensory NCVs with a mild to moderate reduction in the amplitudes, although NCS may be normal in patients with only the myopathy. EMG demonstrates myopathic muscle action potentials (MUAPs), increased insertional activity in the form of positive sharp waves, fibrillation potentials, and occasionally myotonic potentials, particularly in the proximal muscles. Neurogenic MUAPs and reduced recruitment are found in more distal muscles. Nerve biopsy demonstrates autophagic vacuoles within Schwann cells. Vacuoles may also be evident in muscle biopsies. The pathogenic basis of the neuropathy is not known but may be related to the amphiphilic properties of the drug. These agents contain both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions that allow them to interact with the anionic phospholipids of cell membranes and organelles. The drug-lipid complexes may be resistant to digestion by lysosomal enzymes, leading to the formation of autophagic vacuoles filled with myeloid debris that may in turn cause degeneration of nerves and muscle fibers. The signs and symptoms of the neuropathy and myopathy are usually reversible following discontinuation of medication.

AMIODARONE

Amiodarone can cause a neuromyopathy similar to chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. The neuromyopathy typically appears after patients have taken the medication for 2–3 years. Nerve biopsy demonstrates a combination of segmental demyelination and axonal loss. Electron microscopy reveals lamellar or dense inclusions in Schwann cells, pericytes, and endothelial cells. The inclusions in muscle and nerve biopsies have persisted as long as 2 years following discontinuation of the medication.

COLCHICINE

Colchicine can also cause a neuromyopathy. Patients usually present with proximal weakness and numbness and tingling in the distal extremities. EDx reveals features of an axonal polyneuropathy. Muscle biopsy reveals a vacuolar myopathy, whereas sensory nerves demonstrate axonal degeneration. Colchicine inhibits the polymerization of tubulin into microtubules. The disruption of the microtubules probably leads to defective intracellular movement of important proteins, nutrients, and waste products in muscle and nerves.

THALIDOMIDE

Thalidomide is an immunomodulating agent used to treat multiple myeloma, GVHD, leprosy, and other autoimmune disorders. Thalidomide is associated with severe teratogenic effects as well as peripheral neuropathy that can be dose-limiting. Patients develop numbness, painful tingling, and burning discomfort in the feet and hands and less commonly muscle weakness and atrophy. Even after stopping the drug for 4–6 years, as many as 50% patients continue to have significant symptoms. NCS demonstrate reduced amplitudes or complete absence of SNAPs, with preserved conduction velocities when obtainable. Motor NCS are usually normal. Nerve biopsy reveals a loss of large-diameter myelinated fibers and axonal degeneration. Degeneration of dorsal root ganglion cells has been reported at autopsy.

PYRIDOXINE (VITAMIN B6) TOXICITY

Pyridoxine is an essential vitamin that serves as a coenzyme for transamination and decarboxylation. However, at high doses (116 mg/d), patients can develop a severe sensory neuropathy with dysesthesias and sensory ataxia. NCS reveal absent or markedly reduced SNAP amplitudes with relatively preserved CMAPs. Nerve biopsy reveals axonal loss of fiber at all diameters. Loss of dorsal root ganglion cells with subsequent degeneration of both the peripheral and central sensory tracts have been reported in animal models.

ISONIAZID

One of the most common side effects of isoniazid (INH) is peripheral neuropathy. Standard doses of INH (3–5 mg/kg per day) are associated with a 2% incidence of neuropathy, whereas neuropathy develops in at least 17% of patients taking in excess of 6 mg/kg per day. The elderly, malnourished, and “slow acetylators” are at increased risk for developing the neuropathy. INH inhibits pyridoxal phosphokinase, resulting in pyridoxine deficiency and the neuropathy. Prophylactic administration of pyridoxine 100 mg/d can prevent the neuropathy from developing.

ANTIRETROVIRAL AGENTS

The nucleoside analogues zalcitabine (dideoxycytidine or ddC), didanosine (dideoxyinosine or ddI), stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC), and antiretroviral nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) are used to treat HIV infection. One of the major dose-limiting side effects of these medications is a predominantly sensory, length-dependent, symmetrically painful neuropathy. Zalcitabine (ddC) is the most extensively studied of the nucleoside analogues, and at doses greater than 0.18 mg/kg per day, it is associated with a subacute onset of severe burning and lancinating pains in the feet and hands. NCS reveal decreased amplitudes of the SNAPs with normal motor studies. The nucleoside analogues inhibit mitochondrial DNA polymerase, which is the suspected pathogenic basis for the neuropathy. Because of a “coasting effect,” patients can continue to worsen even 2–3 weeks after stopping the medication. Following dose reduction, improvement in the neuropathy is seen in most patients after several months (mean time about 10 weeks).

HEXACARBONS (n-HEXANE, METHYL n-BUTYL KETONE)/GLUE SNIFFER’S NEUROPATHY

n-Hexane and methyl n-butyl ketone are water-insoluble industrial organic solvents that are also present in some glues. Exposure through inhalation, accidentally or intentionally (glue sniffing), or through skin absorption can lead to a profound subacute sensory and motor polyneuropathy. NCS demonstrate decreased amplitudes of the SNAPs and CMAPs with slightly slow CVs. Nerve biopsy reveals a loss of myelinated fibers and giant axons that are filled with 10-nm neurofilaments. Hexacarbon exposure leads to covalent cross-linking between axonal neurofilaments that result in their aggregation, impaired axonal transport, swelling of the axons, and eventual axonal degeneration.

LEAD

Lead neuropathy is uncommon, but it can be seen in children who accidentally ingest lead-based paints in older buildings and in industrial workers exposed to lead-containing products. The most common presentation of lead poisoning is an encephalopathy; however, symptoms and signs of a primarily motor neuropathy can also occur. The neuropathy is characterized by an insidious and progressive onset of weakness usually beginning in the arms, in particular involving the wrist and finger extensors, resembling a radial neuropathy. Sensation is generally preserved; however, the autonomic nervous system can be affected. Laboratory investigation can reveal a microcytic hypochromic anemia with basophilic stippling of erythrocytes, an elevated serum lead level, and an elevated serum coproporphyrin level. A 24-h urine collection demonstrates elevated levels of lead excretion. The NCS may reveal reduced CMAP amplitudes, while the SNAPs are typically normal. The pathogenic basis may be related to abnormal porphyrin metabolism. The most important principle of management is to remove the source of the exposure. Chelation therapy with calcium disodium ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), British anti-Lewisite (BAL), and penicillamine also demonstrates variable efficacy.

MERCURY

Mercury toxicity may occur as a result of exposure to either organic or inorganic mercurials. Mercury poisoning presents with paresthesias in hands and feet that progress proximally and may involve the face and tongue. Motor weakness can also develop. CNS symptoms often overshadow the neuropathy. EDx shows features of a primarily axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy. The primary site of neuromuscular pathology appears to be the dorsal root ganglia. The mainstay of treatment is removing the source of exposure.

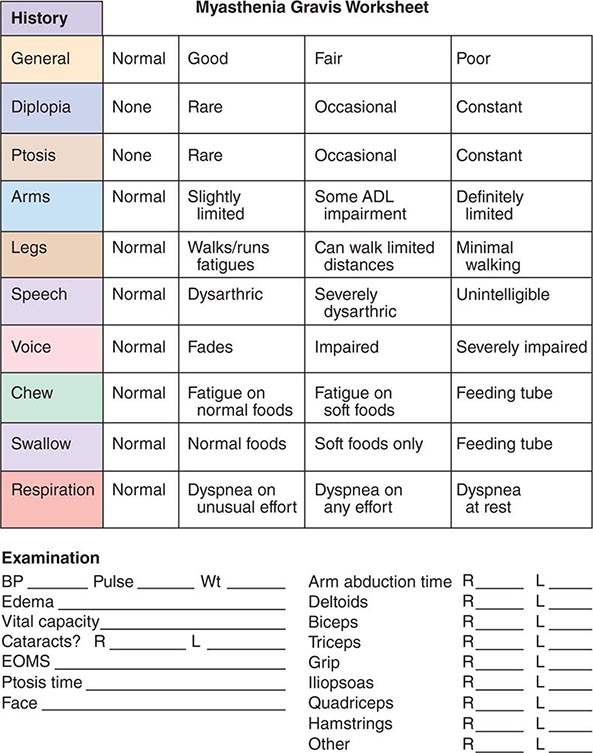

THALLIUM