Chapter 27 Musculoskeletal disorders

With contribution from Greg de Jong

Introduction

A survey of US adults in December 2007 found that 42% of respondents reported that they were in pain on the day of the survey, 1 in 4 experiencing acute pain, with 72% indicating they had experienced pain in the last 12 months. Of particular interest, 70% of people who reported acute pain, 45% recurrent pain and 20% of chronic pain sufferers indicated that they did not seek medical advice for their condition. The common reason given for the reluctance to seek advice included the perception that people take too many pills, a reluctance to take general medication for pain in a specific location, or that oral prescriptive medications upset their stomachs.1

In light of such statistics and concerns it would appear pertinent to investigate all available options in regard to the management of musculoskeletal care. Interestingly, in a further US study, knowledge of complementary health care providers and interventions specific to the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions was found to be surprisingly low, with the exception of chiropractic treatment. However, most respondents indicated that they would be interested in accessing complementary health care for musculoskeletal injury and pain if costs were subsidised and that their doctors considered such interventions as reasonable.2

In Australia, national surveys indicate substantial usage of acupuncture, chiropractic and osteopathic treatments, particularly for back complaints. Approximately 1 in 4 Australians surveyed visited 1 of these providers — 16.1% chiropractors, 9.2% acupuncturists and 4.6% osteopaths — amounting to approximately 32.3 million visits per year, with over 90% considering their treatments to be somewhat helpful or very helpful.3

A British survey of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain demonstrated similarly high levels of usage for all forms of complementary therapies. In the survey, 84% of participants reported having used a complementary treatment in the last year with 65% as present users. Three people used over-the-counter complementary medicines for every 2 who sought treatment from a provider with the most used products being glucosamine and fish oils. Of respondents, 69% used conventional medicines concurrently with their complementary treatment of choice.4

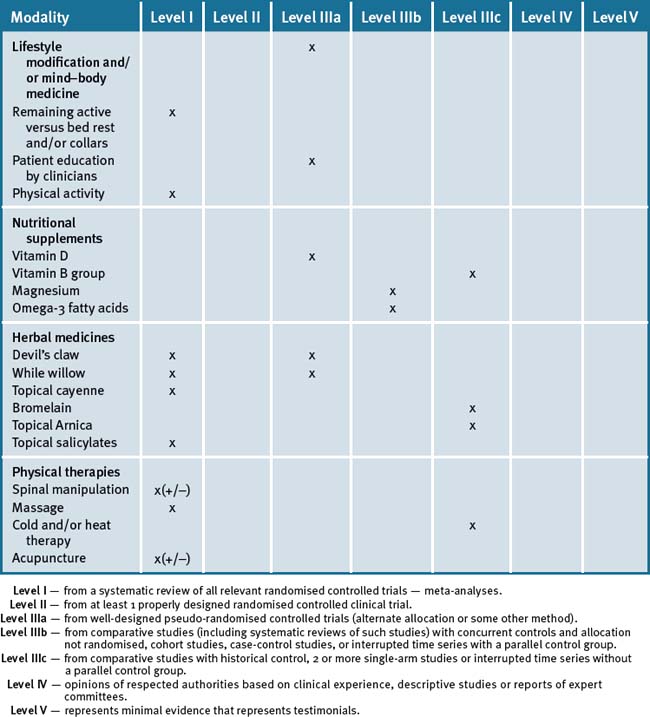

Acute musculoskeletal pain and/or injury management

Acute pain is defined as pain of less than 3 months.5, 6 It may arise as a result of injury, repetitive movement or be insidious in nature. It has been highlighted by the Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group7 that most incidences of acute musculoskeletal pain are of short duration (less than 3 months) and will not lead to chronic pain and disability, although mild symptoms may persist.

Furthermore, in the majority of cases the determination of cause and specific diagnosis is not required, whilst simple interventions, including information, assurance and the maintenance of appropriate levels of activity, when coupled with pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches will be satisfactory without the need for extensive investigation. What is critical is to identify as early as possible the minority of patients who are either presenting with a serious medical condition (‘red flags’) or are at risk of developing chronic musculoskeletal pain due to psychosocial factors (‘yellow flags’).8 (See Tables 27.1 to 27.3.)

Table 27.1 Identifying features (‘red flags’) of serious conditions associated with acute low back pain

| Feature or risk factor | Factor/condition |

|---|---|

(Source: Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group 2003 Evidence-Based Management of Acute Musculoskeletal Pain. National Health and Medical Research Council)

Table 27.2 Identifying features of serious conditions associated with acute thoracic spinal pain

| Feature or risk factor | Condition |

|---|---|

| Fracture | |

| Infection | |

| Tumour | |

| Other serious conditions |

(Source: Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group 2003 Evidence-Based Management of Acute Musculoskeletal Pain. National Health and Medical Research Council)

Table 27.3 Identifying features of serious conditions associated with acute neck pain

| Feature or risk factor | Condition |

|---|---|

| Infection | |

| Fracture | |

| Tumour | |

| Neurological symptoms in the limbs | Neurological condition |

| Cerebrovascular symptoms or signs, anticoagulant use | Cerebral or spinal haemorrhage |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, transient ischaemic attack | Vertebral or carotid aneurysm |

(Source: Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group 2003 Evidence-Based Management of Acute Musculoskeletal Pain. National Health and Medical Research Council)

Lifestyle, mind–body issues and acute musculoskeletal injury

While lifestyle and mind–body medicine interventions may not be necessary during the initial stage of acute injury management, it is the assessment of these factors that form the core tool for identifying those patients who are most likely to progress onto chronic musculoskeletal conditions (‘yellow flags’) and hence require greater monitoring and follow up.8

For instance, in regard to low back pain, psychosocial and occupational factors are considered to have greater clinical value in predicting chronicity than clinical presentation.9, 10 A systematic review of psychosocial factors in 2008 identified that the most pertinent risks of failure to return to work after a low back injury were a low expectation of recovery and fear-avoidance behaviours.11 Depression, job satisfaction and stress levels did not appear to have an impact on the likelihood of return to work after injury.

A variety of evaluation tools, such as the Acute Low Back Screening Tool,8 Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire, Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, Oswestry Low Back Pain and Disability Questionnaire and so forth, have subsequently been developed to assess various aspects of psychosocial behaviours, particularly in regard to low back pain. Where such factors are identified as pertinent during an acute episode of injury early referral to behavioural strategies outlined under chronic musculoskeletal management should be considered.

Remaining active versus bed rest and collars

Current evidence suggests remaining active after an acute musculoskeletal injury is preferable in most instances to bed rest or immobilisation. A Cochrane review in 200512 indicated that advice to remain active was preferable to bed rest for acute low back pain, although there was no indication of difference where sciatic symptoms were present. Fordyce13 compared the use of analgesia, exercise, time contingent and behaviour contingent activity in addressing acute low back pain and found that the latter group who had been advised to ‘let pain be your guide’ were less likely to progress to chronic pain. In the instance of neck pain, remaining active was reported to be of more benefit than rest in a collar after whiplash injuries of the neck.14 Thus it would appear that remaining as active as possible while respecting pain levels is the best encouragement for patients experiencing acute musculoskeletal pain. Exceptions, however, do apply in the instance where musculoskeletal injury is significant enough to require protection from further damage (e.g. strains of ankle and knee ligaments).15

Behavioural therapy

A recent review reported on the rationale and evidence supporting 3 frequently used psychosocial interventions for chronic pain; namely, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), operant behavioural therapy and self-hypnosis training.16 The study concluded that CBT and operant behavioural therapy treatments have a focus on factors that exacerbate or maintain suffering in chronic pain, and should be considered as part of a multidisciplinary treatment paradigm. Whereas self-hypnosis training may be of benefit, it appears to be no more (or less) effective than other relaxation strategies that include hypnotic elements.

Education

A summary of findings on patient education from controlled trials on acute low back pain by the Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Guidelines Group7 indicated that practitioner-delivered information was more effective than brochures and booklets. Furthermore, information provided in the mail was less effective than in person. In regard to neck pain in general, a Cochrane review indicated no strong evidence for the effectiveness of educational interventions.17

Exercise

A Cochrane review18 indicated that for acute low back pain exercise was no more effective than no treatment or other conservative treatments. In the subacute phase limited evidence suggests that a graded exercise program may improve absentee rates. A literature review in 200819 supported this view, indicating that the most appropriate advice at an early stage was the continuation of normal activities as effectively as possible rather than an exercise program. Exercise at the subacute stage (>4 weeks) onwards was indicated to decrease pain and disability, although no specific exercise program was indicated as superior.

A Cochrane review of exercises for acute neck pain indicated limited evidence supporting active range of motion exercises or home-based exercise programs, including both mechanical and whiplash associated disorders.20 Exercise has been found beneficial in terms of short-term recovery and long-term function in relation to rotator cuff disease of the shoulder.21

Nutritional supplements

Vitamin D

Increasing evidence indicates the importance of vitamin D deficiency in muscle pain and weakness. In a study of vitamin D deficiency in a community health clinic, 93% of patients with non-specific musculoskeletal pain were found to have vitamin D deficiency, and 100% of those were under 30 years of age.22 The authors highlighted the fact that vitamin D deficiency should be considered in all patients with non-specific muscular pain, including those not usually expected to be deficient — the young and non-house-bound.

A review of papers on vitamin D deficiency in 2006 concluded that vitamin D deficiency should be considered as a differential diagnosis in the evaluation of musculoskeletal complaints and treated accordingly.23 Furthermore, musculoskeletal weakness (e.g. of the thigh muscles) was an additional consequence of vitamin D deficiency. A pilot study of vitamin D deficiency in chronic pain patients found that in those patients with vitamin D deficiency (26%; serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D<20ng/l) using opioid drugs, the mean morphine equivalent dose and duration of use was significantly higher than non-vitamin D deficient patients.24

It is a misassumption that a sunny environment is necessarily protective against vitamin D deficiency. Case studies in Saudi Arabia and Egypt demonstrate significant relationships between vitamin D deficiency and chronic low back pain.25, 26 In Saudi Arabia 83% of patients with chronic low back pain were found to be vitamin D deficient with the majority successfully treated with vitamin D supplementation over a 3-month period.25 In the Egyptian study 81% of low back pain patients and 60% of controls were found to be vitamin D deficient indicating that despite the sunny climate many Egyptians were vitamin D deficient. Both limited duration of sun exposure and limited area of skin exposure were associated with deficiency findings.26 A small study of urban Australian Aboriginals comparing low back pain subjects with controls also demonstrated a 100% vitamin D deficiency amongst the 8 patients with low back pain.27

Treatment with vitamin D has been found to be effective for many low back pain patients in several case studies. It must be noted, however, that most studies used either intramuscular injections of between 10 and 30 000IU28,29 or high dose supplementation at levels of 50 000IU.30, 31 The one exception was a Saudi Arabian study in which levels of 5000IU/day (<50kg) or 10 000IU/day (>50kg) were used. In all instances clinical improvements were observed in the majority of patients within 3 months.25

A caveat to vitamin D supplementation addresses the question as to whether vitamin D has any effect on diffuse musculoskeletal pain that may be associated with low vitamin D levels. Warner and Arnspiger32 recently reported that low vitamin D levels were not associated with diffuse musculoskeletal pain, and treatment with vitamin D did not reduce pain in patients with diffuse pain and who have low vitamin D levels.

Magnesium and/or alkaline minerals

Anecdotally magnesium is often reported to assist in the alleviation of muscular pain and spasms. Physiologically magnesium plays a significant role in the musculoskeletal system being responsible in part for control of neuronal activity, neuromuscular transmission and muscular contraction/relaxation phases.33

However, whilst studies indicate successful use of magnesium sulfate for tetanic muscle spasms34 and magnesium glycerophosphate in the reduction of muscle spasticity in multiple sclerosis,35 there is minimal current evidence to support or reject magnesium use in the otherwise well patients with musculoskeletal pain/injury.

One open prospective study of 82 patients with chronic low back pain provided an alkaline mineral supplement demonstrated a clinically significant 49% drop on the Arhus Low Back Pain Rating Scale over a 4-week period. Interestingly, of the multi-minerals used in the formula, including potassium, calcium, iron and copper, only magnesium demonstrated changes in serum (11% increase) and plasma readings (3% decrease) after supplementation.36 The authors also noted an increased blood buffering capacity from the alkaline formula and concluded with the view that a disturbed acid-base balance might be responsible for chronic low back pain.36

Omega-3 essential fatty acids

The resolution of acute inflammation is a dynamic process that requires an appropriate host response, tissue protection and resolution of inflammation. Increasing evidence recognises the role of omega-3 derived mediators (e.g. resolvin, protectin) in regulating the resolution of the acute inflammatory process.37, 38 To date no trials have been undertaken in regard to the use of omega-3 supplements during acute inflammation.

However, given the effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for both acute and chronic low back pain, and the assumed role of omega-3 essential fatty acids in the inflammatory process, a controlled study was undertaken amongst non-surgical neck and low back pain patients attending a neurosurgical practice.39 Patients were requested to take 1200mg/day of omega-3 supplements (EPA/DHA) and followed up after 1 month. Although response rate to recall by mail was only 50%, 78% remained compliant to recommended dosage, with 22% doubling the dosage themselves. Sixty percent of patients reported that their overall pain had improved, 60% that joint pain had improved and 59% discontinued their NSAID. Eighty percent reported that they were satisfied with their improvement.39 This early evidence indicates that further studies are required in this area, given the lack of complications associated with omega-3 supplementation as compared to NSAIDs.

B Vitamins

A single randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of 60 patients with non-surgical low back pain found that an active group receiving intramuscular B12 injections showed a statistically significant decrease in pain as measured on an Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and a disability questionnaire. The active group also had a significant decrease in paracetamol use in compare to the placebo group.40

Clinical trials of low back pain have also been undertaken to establish whether B group vitamins (B1 thiamine nitrate 25mg, B6 pyridoxine hydrochloride, B12 cyanocobalamin 0.25mg; 3 x 2 capsules per day for 3 weeks) added to diclofenac can shorten the need for this medication. A clinically significant difference in diclofenac use in favour of the B vitamin group was noted for patients with severe pain at the beginning of the trial.41 However, no further trials have been undertaken to evaluate the analgesic role of the B group vitamins in this regard.

Herbal medicines

A 2007 Cochrane review of herbal medicines for the low back identified 3 herbs; Harpagophytum procumbens (devil’s claw), Salix alba (white willow bark) and Capsicum frutescens (cayenne) as potentially beneficial in reducing low back pain, however, it was noted that the quality of studies were generally poor.42 While other herbs are often recommended for acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions, evidence is usually of low quality, by inference from non-human studies or lacking at present.

Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens)

Reductions in low back pain and muscle stiffness have been reported in a series of double-blind studies using a Devil’s Claw extract Ll 174.43, 44 A double-blind study comparing devil’s claw (50 or 100mg harpagogoside)/day to rofecoxib (12.5mg) found equivalent benefit over a 6 week period,45, 46 with follow up after 1 year47 highlighting that devil’s claw was well tolerated and that treatment gains were sustained.

A recent review investigated 28 trials of which 20 reported adverse events.48 In none of the double-blind RCTs was the incidence of adverse events during treatment with Harpagophytum procumbens higher than during placebo treatment. Also, minor adverse events occurred in approximately 3% of the patients, these being mainly gastrointestinal in nature. A few reports of acute toxicity were found but there were no reports of chronic toxicity. Since the dosage used in most of the studies was at the lower limit and since long-term treatment with Harpagophytum products was advised, more safety data are required.

White willow bark (Salix alba)

In a randomised placebo-controlled study of patients, 39% of active patients treated with white willow bark, standardised to 240mg salicins daily, were found to be pain free. In the control group only 6% achieved the same result over a 4-week trial period.49 In an open trial comparing 240mg salicins daily, 120mg salicins daily and a control group of conventional treatment, results favoured the 240mg salicins daily group (40% pain free over 4 weeks compared to 19% for the 120mg salicin group and 18% for control).50

White willow bark, 240mg salicins daily, has been found to be equivalent to rofecoxib in use for acute episodes of chronic low back pain. The need for rescue dosages of NSAIDs or tramadol was found to be 10% in the white willow bark group and 13% with rofecoxib use.51

Cayenne (Capsicum frutescens)

As noted, a 2007 Cochrane review found 3 low quality trials supporting the use of topical preparations of Capsicum frutescens for low back pain. Cayenne trials were carried out in the form of plaster applications and outcomes were judged to be modest in effect.42

Bromelain

A single open study of the use of bromelian for acute knee pain in the absence of osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis demonstrated that 400mg dosages provided significantly more benefit in pain, function and a decrease in knee joint stiffness as compared to a 200mg dosage.52

Topical analgesia

Arnica

Topical arnica is often advocated to reduce bruising and swelling in acute injury. Whilst no clinical trials have been performed for acute musculoskeletal injury, post-surgical trials involving wound healing after carpal tunnel syndrome (homeopathic arnica and topically applied arnica ointment) indicate reduced pain levels 2 weeks post surgery when compared to placebo subjects.53 Further studies with this gel are required to substantiate its wide spread use for acute injury, swelling and bruising.

Topical salicylates

Salicylate is considered to work as a counter irritant in its role as a topically applied pain reducing agent. A review of the use of topical salicylates for acute injuries such as low back pain, ligamentous strains and mild athletic injuries revealed that 67% of active subjects received greater than 50% pain reduction from topical application as compared to only 18% of controls. No comparison studies have been undertaken to compare the use of such topical applications to other conventional therapies.54

Physical therapies

Manipulation

Reviews are mixed as to the benefits of manipulation in managing acute musculoskeletal back pain. A Cochrane review in 2009 established that manipulation was only more effective when compared to sham treatments or treatments that were considered ineffective or harmful. No clinically significant advantage was noted when compared to general practice care, analgesics, physical therapy, exercise or back school.55 Other reviews, however, have indicated that spinal manipulation may be beneficial in the first 4 weeks post injury.56, 57 A review of the evidence by the American Pain Society/American College of Physicians in 2007 suggested that there was fair evidence for small to moderate benefits from spinal manipulation.58

Two systematic reviews in 2005 of manipulation for acute neck conditions indicated scant evidence for the use of cervical manipulation.59, 60

Massage

A Cochrane review of massage for subacute (4 weeks–3months) low back pain indicated that massage may be of benefit.61

A Cochrane review of massage of mechanical neck disorders made no recommendations due to methodological considerations.62

Cold and/or heat therapies

Despite almost universal acceptance of ice as a first-line treatment to reduce swelling after acute injury, there is a surprising paucity of studies to support or refute its use, with only marginal evidence that ice plus exercise was of benefit after ankle sprains.63, 64 Moderate evidence from a small number of trials indicates that heat wraps may be of benefit during acute episodes of low back pain.65

Acupuncture

A Cochrane review (2009) of the use of acupuncture or dry needling for acute low back pain indicated insufficient evidence to make any recommendations.66 A Cochrane review in 2006 found no trials on acupuncture for acute neck pain.67 A Cochrane review of acupuncture for shoulder pain indicated the possibility of short-term benefit in pain and function, but that evidence was otherwise lacking in its efficacy.68 Acupuncture may also provide short-term relief from lateral elbow pain (tennis elbow), however, no benefit lasting greater than 24 hours has been demonstrated.69

Moreover, a systematic review investigated the effectiveness of acupuncture for non-specific low back pain70 in 23 trials (n = 6359). There was moderate evidence that acupuncture was more effective than no treatment, and strong evidence of no significant difference between acupuncture and sham acupuncture, for short-term pain relief. However, there was strong evidence that acupuncture could be a useful supplement to other forms of conventional therapy for non-specific lower back pain.

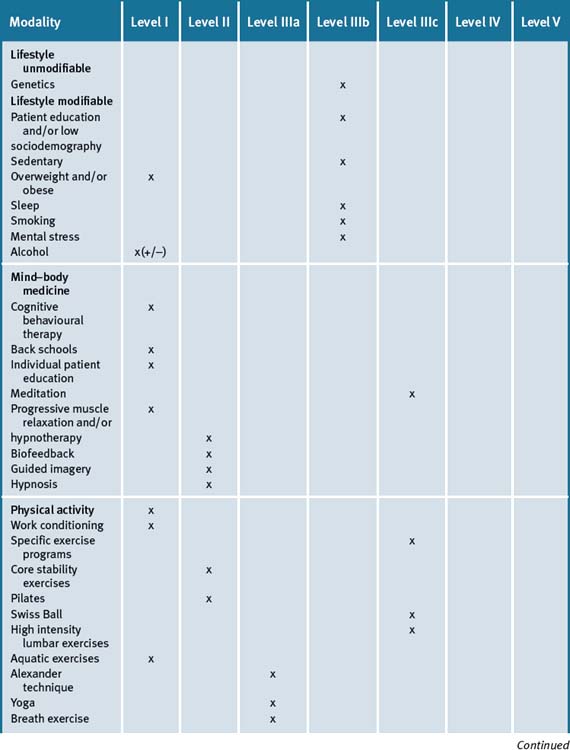

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (e.g. low back pain)

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that in 2004–2005 15% of the Australian population experienced low back pain at a cost of $567 million per year.71 In fact it has been estimated that up to 70% of the community of wealthy nations will experience low back pain in their lifetime, with 2–7% of patients developing chronic low back pain (pain>12 weeks) as a result of an acute episode.72 In approximately 85% of cases a specific diagnosis for low back pain cannot be determined despite diagnostic efforts.72 Even in instances where an initial acute episode is resolved, low back pain often follows a recurrent pattern with re-exacerbations likely.73

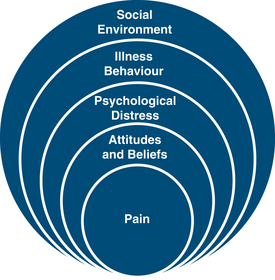

The biopsychosocial model of pain has been adopted to explain the complexities of the pain experience (Figure 27.1).74 Within this approach chronic pain is viewed as a composite response that results from the summation of biological, psychological and social factors individual to the patient’s pain ‘experience’ rather than directly correlating with tissue damage or disease. Although tissue damage may lead to nociception and a painful experience, the level of pain may be modified by many factors such as emotional response, belief structures, personal experience, cultural background, community and work environment and so forth. Alternatively in some instances tissue healing may be complete, yet pain may persist as part of a greater personal experience unique to the individual.

Hence in the context of integrative and complementary medicine the treatment of chronic low back pain may potentially involve the complete spectrum of mind–body therapies. Chronic low back pain should not be viewed solely as a musculoskeletal condition but as an experience of not only the body, but emotions, thought processes, family, social and spiritual network and, in instances of occupational injury, the work community of the patient. However, on the other hand we should not pass over the possibility of prolonged tissue damage or organic imbalance once the patient has entered the classification of chronic pain by assuming that the pain is ‘only’ psychosomatic in origin, for to do so would also risk overlooking the holism that is the individual living within the pain experience.

Lifestyle factors

Genetic

Recent studies indicate genetic influence in the development of some aspects of chronic low back pain. In twin studies related to low back pain, disc height narrowing was the factor found to correlate most with low back pain history, and further found to be genetically correlated. Other genetic correlations were found with the duration of the longest episode of back pain, hospitalisation from back pain and disability from back pain in the year previous to the study.75 Twin studies of adult women demonstrated a heritability of low back pain in adult females in the range of 52–68%, and neck pain in the range of 35–85%.76 A Danish twin study of men and women over the age of 70 indicated a genetic association with low back pain of 25% in men. However, only a modest and non-significant concordance was noted in women such that the conclusion was that genetics did not play a role in low back pain in women over 70.77

Education/socioeconomic factors

Consistent findings indicate that low socioeconomic status are predictive of the risk of low back pain. The results of the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study published in 2004 indicated a 2.9 relative risk loading for widespread areas of pain with a 1.5 to 2.0 risk loading for regional pain conditions including low back pain. Childhood socioeconomic status was to a lesser extent significant in regards to most aspects of pain.78

Low education levels have also been consistently associated with low back pain. For instance, prospective cohort studies in Norway of 38 426 employed men and women aged 29–59 established that the most significant mediating factor for men between education and low back pain was working conditions (authority to plan own work, physically demanding work, concentration and attention and job satisfaction), while in women occupational class, working conditions and lifestyle factors (smoking, BMI, exercise, alcohol) contributed to increased risk of low back pain. However, such mediating factors only reduced the link between education and low back pain by 39%, suggesting an otherwise strong and unexplained independent effect of education on low back pain incidence.79

Physical activity

While physical activity is considered important in preventing and managing low back pain, recent evidence suggests that both the sedentary and over active may be at risk. A Netherlands study of 3364 adults, 25 years and older, drawn from the Dutch population-based Musculoskeletal Consequences Cohort study (1998) identified a modest increase in risk of low back pain in people with sedentary lifestyles (1.31), but also in those involved in physically strenuous activities (1.21), with the relationship being particularly true in women (sedentary = 1.44, physically strenuous = 1.36). Sporting activity was associated with less low back pain (0.78).80

Overweight and obesity

A 2009 systematic review and meta-analysis of the comorbidities of the overweight and obese as defined by BMI identified that both groups had a statistically significant association with chronic low back pain.81 Amongst the elderly (>70), obese subjects (BMI 30–34.9) have twice the likelihood, and severely obese people (BMI >35) 4 times the likelihood, of chronic pain including low back pain than normals.82 A study of the effects of bariatric weight reduction on obese patients presenting with low back pain indicated that substantial weight reduction after bariatric surgery was associated with moderate decreases in pre-existing pain and disability scores.83

Smoking

Analysis of a population-based sample of 29 424 twins aged 12–41 identified a definite link between smoking and incidence of low back pain. Significantly, however, data analysis demonstrated no biological gradient between levels of smoking and measures of low back pain nor did the prevalence of low back pain diminish after the cessation of smoking, suggesting the relationship between smoking and low back pain is not causal in nature.84, 85 A similar relationship between smoking and low back pain has also been demonstrated in adolescents.86 A study of the success rates of smokers in rehabilitation programs for low back pain showed smokers were less likely to complete such programs (dropping from a 86.3% to 75% with smokers), however, outcomes did not differ if the programs were completed.87

Sleep

A 2008 French study of 101 chronic low back pain patients demonstrated that low back pain patients had much poorer sleep quality and higher numbers of sleep disorders when compared to 97 age and sex matched controls. No conclusion was made on whether or not low back pain or poor sleep was the causal factor.88

A 2007 study of 70 chronic back pain patients and 70 gender- and age-matched pain-free controls comparing the sleep patterns of chronic low back pain patients, found that 53% of subjects were rated as insomniacs on the Insomnia Severity Index compared to only 3% of normals. Of 6 variables measured (pain intensity, sensory pain ratings, affective pain ratings, general anxiety, general depression and health anxiety) affective pain levels was found to be the most significant predictor of insomnia, remaining so after the effects of anxiety and depression were controlled for.89

While the preceding study suggests that aspects of low back pain may lead to sleep problems, the reverse may also be the case. A Swedish study of the causal relationship between sleep disturbances using the Malmo Shoulder Neck Cohort followed up 4140 vocationally active healthy 45–64 year olds. Of these people, 11.8% of men and 14.8% of women subsequently developed neck, shoulder or low back pain over the following year and an analysis revealed that preceding sleep problems increased the risk of pain by 1.72% in men and 1.91% in women. As a result it was estimated that 1 in 15–20 cases of newly arising chronic pain could be attributed to sleep difficulties, even after accounting for confounding factors.90 A Finnish study also concluded that sleep problems was one of the factors predictive of developing pain in a 1-year follow up amongst a 40–49 year old subgroup, other factors being mental stress and dissatisfaction with life.91

Mind–body medicine

Cognitive behavioural therapies (CBTs)

A 2007 meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain demonstrated that such interventions lead to improvements in pain intensity, pain-related interference, health-related quality of life scores and depression. The 2 most effective therapies were found to be cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT) and self-regulatory treatments. Additionally, multidisciplinary programs that included psychological components were more effective when compared to active control groups.93 A 2006 Cochrane review differed in its conclusions. Although commenting that CBT and progressive relaxation therapy was more effective than waiting list controls, no significant difference could be found when compared to exercise, nor did behavioural treatments provide any additional benefit to other interventions (e.g. physiotherapy, back education).94

Recently, electromyographic biofeedback — a therapeutic modality used along with other interventions in the treatment of pain — has been suggested to be effective as an adjunct therapy for pain management.95 The review concluded that electromyographic biofeedback was comparable to CBT and relaxation techniques. When added to an exercise program in patients with patellofemoral pain or acute sciatic pain, the reviewers noted no further pain reduction was achieved. However, electromyographic biofeedback may promote active participation and thus in turn may motivate patients to adopt an active role in establishing and reaching goals in rehabilitation. Further research is required to investigate its efficacy on musculoskeletal pain.

Back schools

A Cochrane review of back schools (2004) identified that this form of intervention is often used for chronic low back pain, however, content may vary considerably. This said, there is moderate evidence of improvements in pain and function from back schools provided in the primary and secondary health settings or amongst the general public. Back schools also appear to offer benefits superior to exercise, manipulation, myofascial therapies or advice when performed in an occupation environment. Measures of gain include pain, functional statue and return to work.96

A systematic review in 2007 of back schools with a specific focus on fear-avoidance training concluded that the evidence on back schools was conflicting due to variant inclusion criteria and evidence rules. Brief education in a clinical setting was concluded to have strong evidence of effectiveness, whilst limited or conflicting evidence existed for back books and internet discussions. Interestingly, a review of 3 high quality RCTs found that fear avoidance training as a component of a rehabilitation program was an equally valid intervention as compared to spinal fusion.97

Individual patient education

A Cochrane review of individual education concluded that it was a less effective intervention than more intensive programs of education and rehabilitation for chronic low back pain and no more effective than many single forms of therapy (e.g. CBT, acupuncture, physiotherapy, chiropractic, massage and so forth). No one form of education (written, video, in person) was found to be more effective than another.98

Other mind–body medicine

A structured review of 8 complementary mind-body therapies in older patient groups (>50) with chronic pain suggested that although more evidence was required regarding their efficacy, treatment was feasible to the elderly population. The 8 mind–body therapies included in the review were biofeedback, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, hypnosis, tai chi, qigong and yoga.99

Meditation

Low-level evidence suggests the possibility that meditation is beneficial for chronic low back pain. A qualitative study of mind–body medicine amongst 27 elderly patients (> 65) with moderate chronic low back pain or worse found that they reported numerous benefits, including less pain, greater attention, improved sleep, increased wellbeing and quality of life. The authors recommended further research to establish why mindfulness meditation works and additional benefits to other medical conditions.100

Progressive muscle relaxation/hypnotherapy

A Cochrane review of behavioural therapies indicated moderate evidence from 2 trials in favour of significant positive short-term benefits from progressive muscle relaxation.24 A 1984 study of progressive relaxation found that applied relaxation can significantly improve pain ratings, whilst the addition of an operant conditioning program did not improve outcomes.101

A comparison of relaxation to hypnotherapy demonstrated equivalent benefits in a small trial of 17 patients (relaxation n = 8), with improvements in pain scores and depression noted for both active groups. A placebo group showed no improvements. Hypnotherapy patients (n = 9) also demonstrated less difficulties with getting to sleep, whilst their doctors noted less problems with their use of medication.102

Physical activity/exercise

A Cochrane review of exercise therapy in the treatment of non-specific low back pain indicated that for chronic low back pain exercise was slightly effective in reducing pain and increasing function.103 There was no comment on which form of exercise was preferable.

Work conditioning (work hardening/functional restoration)

Work conditioning programs are intensive exercise regimes (strengthening, aerobic capacity, stretching) intended to mimic work conditions. Such programs have also been defined as consisting of a full day program of activities lasting from 3 to 6 weeks.104 Programs are often multi-modal and include various interventions other than exercise, in particular, cognitive behavioural components. The aim of work conditioning programs is usually specific to return-to-work goals.105

A Cochrane review (2003) found significant evidence that these programs do enhance return to work and work days off in the year following treatment as compared to usual care and advice when a cognitive behavioural approach is undertaken. Evidence is lacking in programs in which a cognitive behavioural approach is not included.105

It is questionable whether results are as impressive when less rigorous programs are undertaken. For instance, a UK study of active exercise (2 hour sessions), education and CBT, 8 sessions over 6 weeks, concluded only a small and non-significant reduction in pain and disability when patients were reassessed after a year. Interestingly, those patients who allocated a preference to such a program prior to the study demonstrated clinically significant improvements in pain and dysfunction, suggesting patient preference was important in outcomes of such a program.106 A study in the Netherlands similarly demonstrated no difference between standard physiotherapy and an intensive group training exercise program at 6, 13 and 52 weeks (at 26 weeks a difference was noted).107

Specific exercise regimes

Core stability exercises

The use of what is known as ‘core stability’ or inter-segmental spinal stabilisation exercises have been advocated for the treatment of low back pain. However, there is no clear evidence that core stability exercises are any more effective than standard physiotherapy treatment (general exercise and manual therapy) or physiotherapy-led pain management classes108, 109 even if they may be more beneficial than daily walks when combined with a graded exercise program.110

Pilates

Pilates is a form of rehabilitative exercise with a relationship to core stability principles. Clinical studies suggest that Pilates exercises performed on specific equipment report significant decreases in pain scores compared to a control group defined as usual care (physician attendance and other health professionals as required).111 However, when Pilates exercises were compared to a standard back school only, equivalent gains in pain and disability were registered in both groups.112

Swiss ball

A single pilot study suggests that a 12-week program of Swiss ball exercises may potentially have benefit in reducing low back pain and disability after a 3 month follow-up period.113

High intensity lumbar exercises

Although it has been hypothesised that high intensity lumbar extension exercises should improve low back pain, the evidence is not clear. A physiotherapy led study comparing high intensity isolated extension exercises to a non-progressive low intensity regime demonstrated that at 8 weeks back symptoms had improved by 39%, however, no other differences were noted at either 8 weeks or at 26 week follow up.114 This outcome has been replicated in a further study where little difference was observed between standard physiotherapy and the lumbar extension group.115 Thus there does not appear to be sufficient evidence to advocate isolated lumbar extension exercises over other interventions.

Aquatic exercises

A systematic review of aquatic exercises performed in 2009 indicates that while aquatic exercises do assist in managing low back pain, the effects are no more advantageous than other interventions.116

Alexander technique

A single 2008 randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the Alexander technique concluded that it was beneficial for reducing chronic low back pain after a 1-year period. It was established that 6 sessions of one-to-one therapy followed by exercise was as effective as 24 sessions.117

Yoga

Preliminary evidence suggests yoga may be of benefit in chronic low back pain. Yoga has been found to be of more benefit than a self-care book in reducing disability and pain after 26 weeks but equivalent to conventional exercise.118 Iyengar yoga has been observed to be beneficial compared to an educational group at 3 months follow up after a 16-week program. Significant reductions were observed in pain intensity, functional disability and medication usage.119 A small pilot study demonstrated Hatha yoga was of benefit compared to a control group over a 6-week period (2 sessions, 2 hour/week) in reducing disability.120 A study of veterans also supports the potential for yoga in aiding back care, however, as with all the above studies, design and numbers make conclusions tentative.121

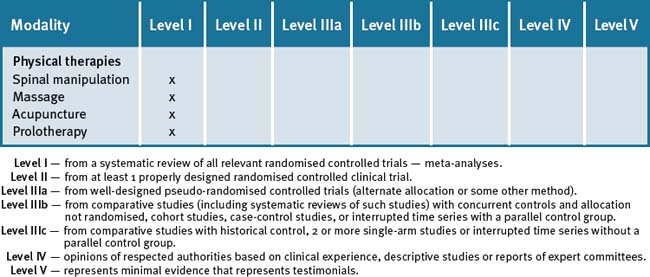

Physical therapies

Manipulation

Manipulation is a therapy predominantly associated with chiropractic treatment, although performed also by physiotherapists and osteopaths.123 A Cochrane review (2004) indicated that although spinal manipulation was more effective than sham and other therapies already shown to be ineffective, manipulation showed no comparative advantage when compared to normal general practitioner care, medication, physical therapy, exercises or back schools.124

However, a review by the American Pain Society/American College of Physicians found that there was good evidence of moderate efficacy for spinal manipulation.125 A further review suggested that spinal manipulation was as efficacious as a prescription of NSAIDs (moderate evidence), effective in the short-term compared to general practitioner care and placebo and over the long-term to physical therapy.126 Chiropractic manipulation was considered efficacious in reducing chronic low back pain in a literature synthesis in 2008, however, it was suggested that additional exercise in conjunction with spinal manipulation would enhance treatment gains.127

Little evidence exists as to the preferred provider of manipulations services (chiropractor, physiotherapist, osteopath). Interestingly, the UK BEAM trial that sought to investigate spinal manipulation concluded that there was more similarities between practices than differences, although a precondition of the trial was that no attempt would be made to define efficacy between programs.128 The finding of this trial was that spinal manipulation for back pain (general) was the most cost-effective tool,129 although the benefits to pain and disability outcomes to the individual were only small to moderate at 3 months and small at 12 months (as compared to exercise; small effect at 3 months, no effect after 12 months).130

The aforementioned trials and reviews suggest differences of opinion exist amongst reviewers when evaluating the benefit of spinal manipulation. It has been argued that the variances in conclusions may be related to not only methodological weaknesses but interpretational bias. A review of reviews on manipulation in 2005 came to the conclusion that there was statistically significant correlations amongst reviews between direction of conclusion (positive towards manipulation), methodological quality (low) and authorship by osteopaths and chiropractors as compared to negative results being associated with quality reviews from other professions.131 Thus it appears that care needs to be taken in interpreting the available evidence for the effectiveness of manipulation for chronic low back pain.

Massage

A Cochrane review (2008) found that massage appeared to be effective in reducing pain and increasing function when compared to a sham treatment. It further found that massage provided similar benefits to exercise and superior benefits to joint mobilisation, relaxation therapy, physical therapy, acupuncture and self-care education. Benefits could last up to a year after the end of massage sessions. Acupuncture massage appeared to provide better results to Swedish massage, while Swedish massage demonstrates similar results to Thai massage.132

Interestingly, neuro-reflexotherapy has been found to be efficacious in low back pain according to a 2006 Cochrane review, however, only as performed in specialist clinics in Spain. No inference can be made at present as to whether this form of treatment is successful away from this environment.133

Acupuncture

A 2009 Cochrane review of acupuncture and dry needling for low back pain demonstrated that acupuncture was more effective than no or sham treatments yet no more beneficial than other therapies. However, acupuncture has been found to be of small benefit in providing short-term pain relief in combination with other therapies. Dry needling also appears to be of benefit when added to other conventional treatments. Studies, however, were of low methodological value, and further investigations are required.134

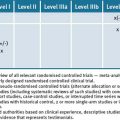

Conclusion — chronic musculoskeletal pain and/or injury

Clinicians should be aware that in the absence of evidence of harm, a range of options are potentially useful to the individual patient given that one of the strengths of integrative medicine is its application to individual patients. Table 27.5 summarises the levels of evidence for some CAM therapies for chronic musculoskeletal pain/injury conditions.

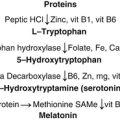

Clinical tips handout for patients — acute injury

1 Reassurance

3 Physical therapies

4 Supplementation

Omega-3 (fish oils)

Vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol)

Magnesium

Clinical tips handout for patients — chronic musculoskeletal pain and/or injury

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body therapies

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

6 Physical therapies

7 Supplementation

Omega-3 (fish oils)

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferal)

Magnesium + malic acid

Herbs

Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens)

Willow bark (Salix alba)

1 New Survey Finds Majority of Americans in Pain. Online. Available: www.reuters.com.article/pressRelease/idUS157460+23-Jan-2008+PRN20080123 (accessed 9 June 2009).

2 Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Connelly M.T., et al. Complementary and alternative medical therapies for chronic low back pain: What treatments are patients willing to try? BMC Complement Alt Med. 2004 Jul 19;4:9.

3 Xue C.C., Zhang A.L., Lin V. Acupuncture, chiropractic and osteopathy use in Australia: a national population survey. BMC Public Health. 2008 Apr 1;8:105.

4 BMV Family Practice. The use of complementary and alternative medicine, and conventional treatment, among primary care consulters with chronic musculoskeletal pain. BMV Family Practice 4. May 2007;8:26. doi:10

5 Bonica J.J. The Management of Pain. Lea and Febiger. 1953. doi:0.1186/1471-2296-8-26

6 Merskey H. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6:249-252.

7 Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group. Evidence Based Management of Acute Musculoskeletal Pain. National Health and Medical Research Council; 2003.

8 New Zealand Guidelines Group. New Zealand Acute Low Back Pain Guide 2004.

9 Truchon M., Fillion L. Biopsychosocial determinants of chronic disability and low back pain: a review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2000;10:117-142.

10 Wessels T., van Tulder M., Sigl T., et al. What predicts outcome in non-operative treatments of chronic low back pain? A systematic review. Eur Spin J. 2006 Nov;15(11):1633-1644.

11 Iles R.A., Davidson M., Taylor N.F.. Psychosocial predictors of failure to return to work in chronic no-specific low back pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2008 Aug 65;8:507-517. Epub 2008 Apr 16

12 Hagen K.B., Jamtevedt G., Hilde G., et al. The updated Cochrane review of bed rest for low back pain. Spine. 2005 Mar 1;30(5):542-546.

13 Fordyce W.E., Brockway J.A., Bergman J.A., et al. Acute back pain: a control group comparison of behavioural vs traditional management methods. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1986;9:127-140.

14 Borchgrevink G.E., Kaasa A., McDonagh D., et al. Acute treatment of whiplash neck sprain injuries. A randomised trial of treatment during the first 14 days after a car accident. Spine. 1998;23:25-31.

15 Kerkhoffs G.M., Struijs P.A., Assendelft W.J., et al. Different functional treatment strategies for acute lateral ankle ligaments. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2002. Art. No CD002938. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002938

16 Molton I.R., Graham C., Stoelb B.L., et al. Current psychological approaches to the management of chronic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20(5):485-489.

17 Haines T., Gross A., Goldsmith C.H., et al. Patient education for neck pain with or without radiculopathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2008. Art. No CD005106. doi: 1002/14651868. CD005106.pub2

18 Hayden J.A., van Tulder M.W., Malmivarra A., et al. Exercise Therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 3, 2005 Jul 20. CD000335

19 Henchoz Y., Kai Lik So. A. Exercise and non-specific low back pain: a literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2008 Oct;75(5):533-539. Epub 2008 Sep 17

20 Kay T.M., Gross A., Goldsmith C.H., et al. Exercise for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2005. Art. No. CD004250. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004250.pub3

21 Green S., Buchbinder R., Hetrick S.E. Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 2):2003. Art. No; CDOO4258. doi. 10.1002/14651858.CD004258

22 Plotnikoff G.A., Qigley J.M. Prevalence of severe hypovitaminosis D in patients with persistent, non-specific musculoskeletal pain. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2003;78:1463-1470.

23 Heath K.N., Elovic E.P. Vitamin D deficiency: implications in the rehabilitation setting. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:916-923.

24 Turner M.K., Hooten W.M., Schmidt J.E., et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of Vitamin D inadequacy among patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2008 Nov;9(8):979-984.

25 Al Faraj S., Al Mutairi K. Vitamin D deficiency and chronic low back pain in Saudi Arabia. Spine. 2003 Jan 15;28(2):177-179.

26 Lofti A., Abdel-Nasser A.M., Hamdy A., et al. Hypovitaminosis D in female patients with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Nov;26(11):1895-1901.

27 Benson J., Wilson A., Stocks N., et al. Muscle pain as an indicator of vitamin D in an urban Australian Aboriginal population. MJA. 2006 July 17;185(2):76-77.

28 Torrente de la Jara De, Precund A., Favrat B. Musculoskeletal pain in female asylum seekers and hypovitaminosis D3. BMJ. 2004;329:156-157.

29 Glerup H., Mikkelsen L., Poulser L., et al. Hypovitaminosis myopathy without biochemical signs of osteomalacic bone involvement. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:419-424.

30 Gloth F.M., Lindsay Jm, Zelesnick L.B., et al. Can vitamin D deficiency produce an unusual pain syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1662-1664.

31 Prabhala A., Garg R., Dandona P. Severe myopathy associated with vitamin D deficiency in western New York. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1199-1203.

32 Warner A.E., Arnspiger S.A. Diffuse musculoskeletal pain is not associated with low vitamin D levels or improved by treatment with vitamin D. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14(1):12-16.

33 Altura B.M., Altura B.T. Roel of Magnesium in pathophysiological processes and the clinical utility of magnesium ion selective electrodes Scand. J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1996;226:211-234.

34 Attgalle D., Rodrigo N. Magnesium as first line therapy in the management of tetanus: a prospective study of 40 patients. Anaesthesia. 2002 Aug;57(8):811-817.

35 Rossier P., van Erven S., Wade D.T. Effect of magnesium oral therapy on spasticity in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2000 Nov;7(6):741-744.

36 Vormann J., Worlitschek M., Goedecke T., et al. Supplementation with alkaline minerals reduces symptoms in patients with chronic low back pain. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2001;15(2-3):179-183.

37 Schwab J.N., Chiang N., Arita M., Serhan C.N. Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation resolution programmes. Nature. 2007 Jun 14;447(7146):869-874.

38 Serhan C.N.. Novel eicosanoid and ocosanoid mediators: resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005 Mar 8;2:115-121..

39 Maroon J.C., Bost J.W. Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oils) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain. Surg Neur. 2006 April;65(4):326-331.

40 Mauro G.L., Martorana U., Cataldo P., et al. Vitamin B12 in low back pain: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Med Pharmacol Sci. 2000 May-Jun;4(3):53-58.

41 Bruggemann G., Koehler C.O., Koch E.M. Results of a double-blind study of diclofenac + vitamin B1, B6, B12 versus diclofenac in patients with acute pain of the lumbar vertebrae. A multicenter study Klin Wochenschr. 1990 Jan 19;68(2):116-120.

42 Gagnier J.J., van Tulder M.W., Berman B., et al. Herbal Medicine for low back pain: a Cochrane review. Spine. 2007 Jan 1;32(1):82-92.

43 Laudahn D., Walper A. Efficacy and tolerance of Harpogophytum extract Ll 174 in patients with chronic non-radicular back pain. Phyto Res. 2001;15(7):621-624.

44 Gobel H.A., et al. Effects of Harpogophytum procumbens Ll 174 (devil’s claw) on sensory, motor and vascular muscle reagibility in the treatment of unspecific back pain. Schmertz. 2001;15(1):10-18.

45 Chrubasik S., et al. Effectiveness of Harpogophytum extract WS1531 in the treatment of exacerbation of low back pain: a randomised placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1999;16(2):118-129.

46 Chrubasik S., et al. A randomised double-blind pilot study comparing Doloteffin(R) and Vioxx(R) in the treatment of low back pain. Rheumatology. 2003;42(1):141-148.

47 Chrubasik S, et. al. A 1 year follow up after a pilot study with Doloteffin(R) for low back. Pain Phytomedicine 2205; 12(1-2):1–9

48 Vlachojannis J., Roufogalis B.D., Chrubasik S. Systematic review on the safety of Harpagophytum preparations for osteoarthritic and low back pain. Phytother Res. 2008;22(2):149-152.

49 Chrubasik S., et al. Treatment of low back pain exacerbations with willow bark extract: a randomised double-blind study. Am J Med. 2000;109(1):9-14.

50 Chrubasik S., et al. Potential economic impact of using a proprietary willow bark extract in outpatient treatment of low back pain: an open non randomised study. Phytomedicine. 2001;8(4):241-251.

51 Chrubasik S., et al. Treatment of low back pain with a herbal synthetic ant-rheumatic: a randomised control study: willow bark extract for low back pain. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40(12):1388-1393.

52 Walker A.F., Bundy R., Hicks S.M., et al. Bromelain reduces mild acute knee pain and improves well being in a dose dependent fashion in an open study of otherwise healthy adults. Phytomedicine. 2002 Dec;9(8):681-686.

53 Jeffrey S.L., Belcher H.J. Use of arnica to relieve pain after carpal tunnel release surgery. Alter Ther Health Med. 2002 Mar-April;8(2):66-68.

54 Mason L., Moore R.A., Edwards J.E., et al. Systematic review of efficacy of topical rubefacients containing salicylates for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328:995-998.

55 Assendelft WJ, Morton SC, Yu EI, et al. Spinal manipulation therapy for low back pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004 Issue 1 Art No. CD000447. doi: 10. 1002/14651858. CD000447.pub 2.

56 Smith D., McMurray N., Disler P. Early Intervention for acute back injury: can we finally develop an evidence based approach? Clin Rehabil. 2002 Feb;16(1):1-11.

57 Swenson R., Haldeman A. Spinal manipulative therapy for low back pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003 Jul-Aug;11(4):228-237.

58 Chou R, Huffman LH. American Pain Society, American College of Physicians Nonpharmacological therapies of acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Soceity/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline Ann Intern Med 2007 Oct 2;147(7):492–504.

59 Vernon H.J., Humphreys B.K., Hagino C.A. A systematic review of conservative treatments for acute pain not due to whiplash. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005 Jul-Aug;28(6):443-448.

60 Haneline M.T. Chiropractic manipulation and acute neck pain: a review of the evidence. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005 Sep;28(7):520-525.

61 Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T. Massage for low back pain Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Art.No.: CD001929. doi 10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub2.

62 Haraldsson B., Gross A., Myers, et al. Massage for mechanical neck disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006. Art. No.:CD004871. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004871.pub3

63 Bleakley C., NcDonough S., MacCauley D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft tissue injury: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2004 Jan-Feb;32(1):251-261.

64 Collins N.C. Is ice right? Does cryotherapy improve outcome for acute soft tissue injury? Emerg Med J. 2008 Feb;25(2):65-68.

65 French SD, Cameron M, Walker BF, et al. Superficial heat or cold for low back pain Cochrane Database Systematic Review 2006 Jan 25; (1): CD004750.

66 Furian AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin D, et. al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 1. Art. No:CDOO1351. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2.

67 Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR, et. al. Acupuncture of neck disorders Cochrane Data Base of Systematic Reviews 2006 Issue 3 Art. No.:CD004870. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub.3.

68 Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick SE. Acupuncture for shoulder pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005319. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005319.

69 Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, et. al. Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003527. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003527.

70 Yuan J., Purepong N., Kerr D.P., et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine. 2008;33(23):E887-E900.

71 Musculoskeletal conditions in Australia. a snapshot 2004-2005 2004-2005. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2006.

72 Deyo R.A., Rainville J., Kent D.L. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA. 1992;268:760-765.

73 Waddell G. The clinical course of low back pain. In: The back pain revolution. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:103-117.

74 Engel G. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

75 Battie M.C., Vidernan T., Levalahti E., et al. Heritability of back pain and the role of disc degeneration. Pain. 2007 Oct;131(3):272-280.

76 MacGregor A.J., Andrew T., Sambrook P.N., et al. Structural, psychological, and genetic influences on low back and neck pain: a study of adult female twins. Arthrititis Rheum. 2004 Apr 15;51(2):160-167.

77 Hartvigsen J., Christensen K., Frederiksen H., et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to back pain inold age: a study of 2108 danish twins aged 70 and older. Spine. 2004 Apr 15;29(8):897-901. Discussion 092

78 McFarlane G.J., Norris G., Atherton, et al. The influence of socioeconomic status on reporting of regional and widespread musculoskeletal pain: results from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Oct 24.

79 Hagen K.B., Tambs K., Bjerkedal T. What mediates the inverse association between education and occupational disability from back pain? – a prospective cohort study from the Nord-Trondelag health study in Norway. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Sep;63(5):1267-1275.

80 Heneweer H., Varness L., Pricavet H.S. Physical activity and low back pain: a U shaped relationship. Pain. 2009 May;143(1-2):21-25.

81 Guh D.P., Zhang W., Barnsback N., et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009 Mar 25;9:88.

82 McCarthy L.H., Bigal M.E., Katz M., et al. Chronic pain and obesity in elderly people: results from the Einstein study. J Am Geriatric Soceity. 2009 Jan;57(1):115-119.

83 Khouier P., Black M.H., Crookes P.F., et al. Prospective assessment of axial pain symptoms before and after bariatric weight reduction surgery. Spine J. 2009 Apr 6.

84 Leboeuf-Yde C., Kyvik K.O., Bruun N.H. Low back pain and lifestyle: Part 1. Information from population based sample of 29,424 twins. Spine. 1998 Oct 15;23(20):2207-2213.

85 Leboeuf–Yde C. Smoking and low back pain. A systematic literature review of 41 journal articles reporting epidemiological studies. Spine. 1999 Jul 15;24(14):1463-1470.

86 Mikkonen P., Leinos-Arjas P., Remes J., et al. Is smoking a risk factor for low back pain in adolescents? A prospective cohort study. Spine. 2008 Mar 11;33(5):527-532.

87 McGeary D., Mayer T., Gatchel R., et al. Smoking status and psychosocioeconomic outcomes of functional restoration in patients with chronic spinal stability. Spine. 2004;4(2):170-175.

88 Marty M., Rozenberg S., Duplan B., et al. Quality of sleep in patients with chronic low back pain: a case control study. Eur Spine J. 2008 June;17(6):839-844.

89 Tang N.K., Wright K.J., Salkovskis P.M. Prevalence and correlates of clnical insomnia co-occurring with chronic back pain. PJ Sleep Res. 2007;16(1):85-95.

90 Carnivet S., Ostergren Po, Chroi B. Sleeping Problem as a risk factor for subsequent musculoskeletal pain and the role of job strain: results from a one year follow up of the Malmo Neck Study. Cohort Int j Beh Med. 2008;15(4):254-262.

91 Miranda H., Viikari-Juntura E., Punnett L., et al. Occupational loading, health behaviour and sleep disturbances as a predictor of low back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008 Dec;34(6):411-419.

92 Leboeuf-Yde. Alcohol and low back pain: a systematic review J Manipulative. Therapy. 2000 June;23(5):343-346.

93 Hoffman B.M., Papas R.K., Chatkoff D.K., et al. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychol. 2007 Jan;26(1):1-9.

94 Ostelo R., van Tulder M., Vlaeyen J. Behavioural Treatment for chronic pain. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2006.

95 Angoules A.G., Balakatounis K.C., Panagiotopoulou K.A., et al. Effectiveness of electromyographic biofeedback in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. Orthopedics. 2008;31(10):pii. orthosupersite.com/view.asp?rID=32085

96 Heymans M., van Tulder M., Esmail R., et al. Back schools for non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews. (Issue 4):2004. Art. No. CDoooo261 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000261.pub 2

97 Brox I., Reikeras O., Nygaard O., et al. Lumbar instrumented fusion compared with cognitive intervention and exercise in patients with chronic back pain after previous surgery for disc herniation: a prospective randomised controlled study. Pain. 2006 May;122(1-2):145-155.

98 Engers AJ, Jellerma P, Wensing M, et al. Individual Patient Education for low back pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008 Issue 1 Art. No.: CD004057. doi: 1002/14651858.CD004047.pub.3.

99 Morone N.E., Greco C.M. Mind-body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review. Pain Med. 2007 May-Jun;8(4):359-375.

100 Morone N.E., Lynch C.S., Greco S.M., et al. ‘I felt like a new person.’ The effect of mindfulness on older patients with chronic pain: qualitative narrative analysis of diary entries. J Pain. 2008 Sep;9(9):841-848.

101 Linton S.J., Gotestam K.G. A controlled study of the effects of applied relaxation and applied relaxation plus operant procedures in the regulation of chronic pain. BR J Clin Psychol. 1984 Nov;23(Pt 4):291-299.

102 McCauley J.D., Thelan M.H., Frank R.G. Hypnosis compared to relaxation in the outpatients management of chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983 Nov;64(11):548-552.

103 Hayden J.A., van Tulder M.W., Malmivaara A., et al. Exercise therapy for treatment of non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2005. CD000335

104 Poiraudeau S., Rannou F., Revel M. Functional Restoration for low back pain: a systematic review. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007 Jul;50(6):425-429. 419–24

105 Schonstein E., Kenny D.T., Keating J.L., et al. Work conditioning, work hardening and functional restoration for workers with back and neck pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 3):2003. Art. No.: CD001822. doi 10.1002/14651858.CD001822

106 Johnson Re, Jones Gt, Wiles N.J. Active exercise, education and cognitive behavioural therapy for persistent disabling low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Spine. 2007 Jul 1;32(15):1578-1585.

107 Van der Roer N., van Tulder M., Barendse J., et al. Intensive group training protocol versus guideline physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2008 Sep;17(9):1193-1200.

108 Cairns M.C., Foster N.E., Wright C. Randomised controlled trial of specific spinal stabilisation exercises and conventional physiotherapy for recurrent low back pain. Spine. 2006 Sep 1;31(19):E670-E681.

109 Critchley D., Ratcliffe J., Noonan, et al. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce chronic low back pain disability: a pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation. Spine. 2007 June 15;32(14):1474-1481.

110 Rasmussen-Barr E., Ang B., Arvidsson I., et al. Graded exercise for recurrent low back pain: a randomised, controlled trial with 6, 12, and 36 months follow ups. Spine. 2009 Feb 1;34(3):221-228.

111 Rydeard R., Leger A., Smith D. Pilates-based therapeutic exercise: effect on subjects with non-specific chronic low back pain and functional disability: a randomised controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006 Jul;36(7):472-484.

112 Donzelli S., Di Domenico E., Cova Am, et al. Two differential techniques in the rehabilitation of low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eura Medicophys. 2006 Sep;42(3):205-210.

113 Marshall P.W., Murphy B.A. Evaluation of functional and neuromuscular changes after exercise rehabilitation for low back pain using a Swiss Ball: a pilot study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006 Sep;29(7):550-560.

114 Harts C.C., Helmhout Ph, de Rie R.A. A high intensity lumbar extensor strengthening program is little better than a low intensity program or a waiting list control group for chronic low back pain: a randomised control clinical trial. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54(1):23-31.

115 Helmhout PH, Harts CC, Viechtbauer W, et. al. Isolated lumbar extensor strengthening versus regular physical therapy in an army working population with nonacute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil Sep; 89(9):1675–85

116 Waller B., Lambeck J., Daly D. Therapeutic aquatic exercise in the treatment of low back pain: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009 Jan;23(1):3-14.

117 Little P., Lewith G., Webley F., et al. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008;337:884.

118 Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Erro J., et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self care book for chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 20;143(12):849-856.

119 William K.A., Petronis J., Smith D., et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005 May;115(1-2):107-117.

120 Galantino M.L., Bzdewka T.M., Eisser-Russo J.L., et al. The impact of modified Hatha Yoga on chronic low back pain. Altern Ther health Med. 2004 Mar-April;10(2):56-59.

121 Grossel E.J., Weingart K.R., Aschbacher K., et al. Yoga for veterans with chronic low back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Nov;14(9):1123-1129.

122 Mehling We, Hamel K.A., Acree M., et al. Randomized, controlled trial of breath therapy for patients with chronic low back pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005 Jul-Aug;11(4):44-52.

123 Swenson R., Haldeman S. Spinal Manipulation therapy for low back pain. A Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003 Jul-Aug;11(4):228-237.

124 Assendelft W.J., Morton S.C., Yu E.I., et al. Spinal manipulation therapy for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2004. Art No. CD000447 doi: 10. 1002/14651858. CD000447.pub 2

125 Assendelft W.J., Morton S.C., Yu E.I., et al. Spinal manipulation therapy for low back pain Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2004. Art No. CD000447 doi: 10. 1002/14651858. CD000447.pub 2

126 Bronfort G., Haas M., Evans, et al. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine. 2004 May-June;4(3):335-356.

127 Lawrence D.J., Meeker W., Branson R., et al. Chiropractic management of low back pain and low back pain related leg complaints: a literature review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 Nov-Dec;31(9):659-674.

128 Harvey E., Burton A.K., Moffet J.K., et al. Spinal manipulation for low back pain: a treatment package agreed to by the UK chiropractic, osteopathy and physiotherapy professional associations. Man Ther. 2003 Feb;8(1):46-51.

129 Uk Beam. Trial Team United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: cost effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 2004 Dec 11;329(7479):1381.

130 Uk Beam. Trial Team United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: cost effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 2004 Dec 11;329(7479):1377.

131 Canter P.H., Ernst E. Sources of bias in reviews of spinal manipulation for back pain. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2005 May;117(9-10):333-341.

132 Furlan Ad, Imamura M, Dryden T. Massage for low back pain. Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Art.No.: CD001929. doi 10.1002/14651858.CD001929.pub2.

133 Urrutia G., Burton A.K., Morral A. Neuroreflexotherapy for non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Data base of Systematic Reviews. (3):2006.

134 Furian Ad, van Tulder M.W., Cherkin D., et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (Issue 1):2005. Art. No:CDOO1351. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2

135 Dagenais S., Yelland M.J., Del Mar C. Prolotherapy injections for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic. Reviews. (Issue 2):2007. Art. No.: CDoo4059 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004059.pub3