Chapter 9 Musculocutaneous Nerve

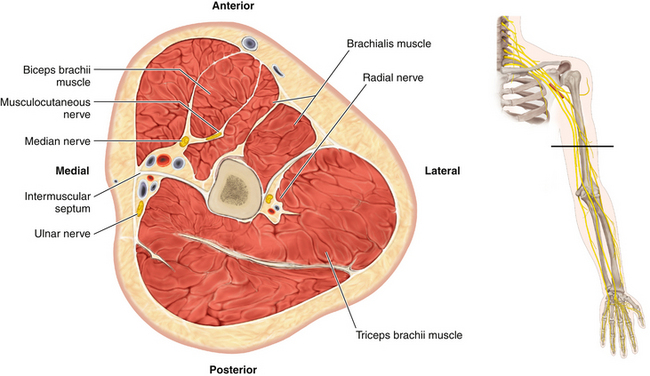

Anatomy

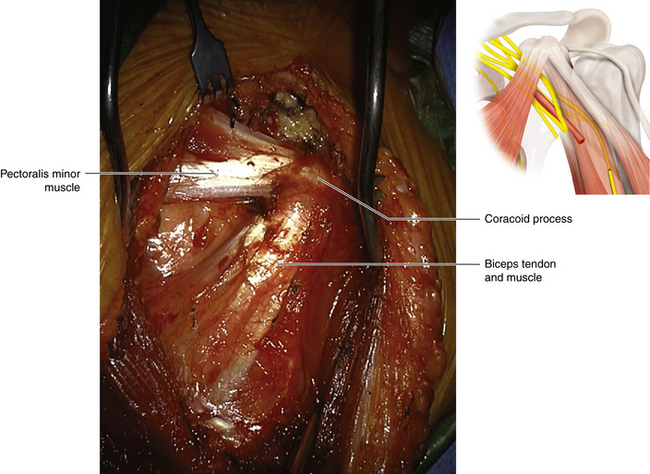

• The short head of the biceps arises from the tip of the coracoid process, lateral to its tendon of joint origin with the coracobrachialis (Figure 9-1). The long head arises from the supraglenoid tubercle. The biceps muscle, formed from this dual origin, is inserted by a tendon into the tuberosity of the radius.

• At its insertion, the tendon sends a medial fascial expansion, the bicipital aponeurosis, medially to thicken the investing fascia and gain attachment to the ulna.

• The median nerve lies under the bicipital aponeurosis, medial to the biceps tendon. The posterior interosseous nerve lies lateral to the tendon.

• The brachialis arises from the anterior aspect of the humerus and is inserted into the tuberosity of the ulna. The biceps and brachialis are strong flexors of the elbow joint. With the elbow flexed, the biceps is the key supinator of the forearm.

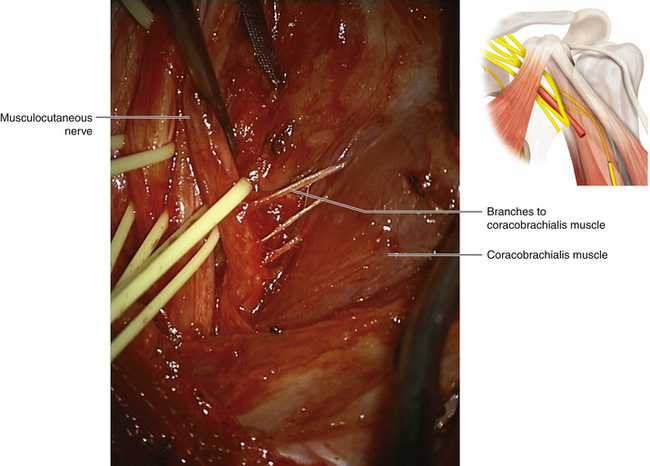

• The coracobrachialis arises from the coracoid process and is inserted into the humerus. Its importance lies in its value as a landmark in operations on the musculocutaneous nerve and not in its function (Figure 9-2).

• The radial nerve is a partial supplier of the brachialis, but not a significant one. In the absence of C6 function (conveyed by the upper trunk, anterior division, and musculocutaneous nerve to the elbow flexors), the radial nerve–supplied brachioradialis, not the trivial segment of brachialis supplied by the radial, assumes the function of weaker elbow flexion.

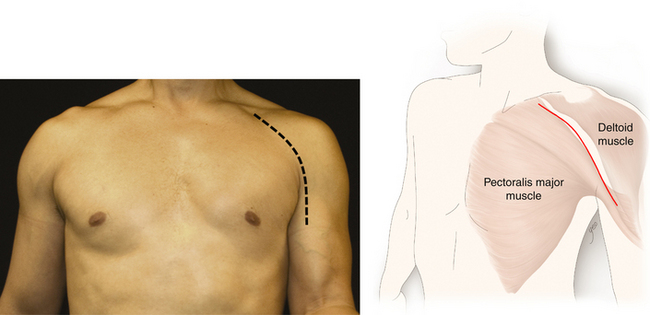

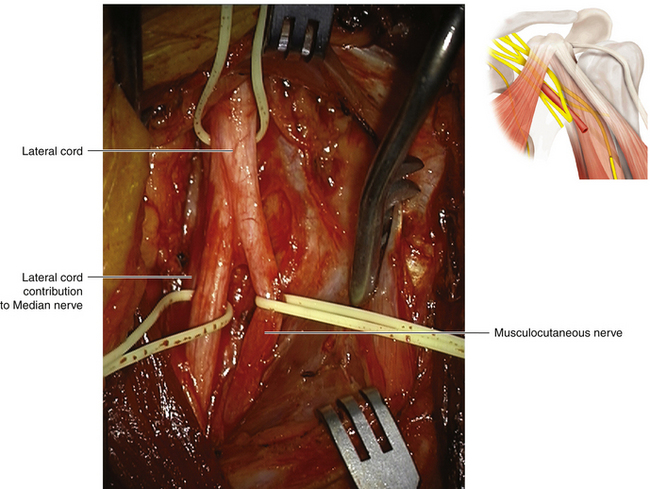

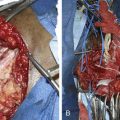

Technique

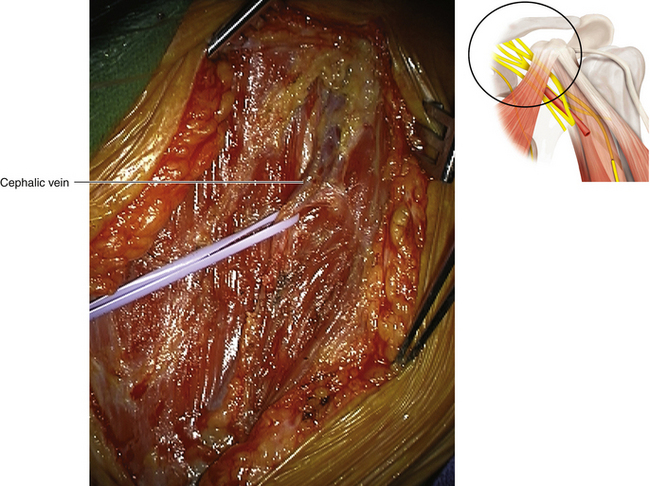

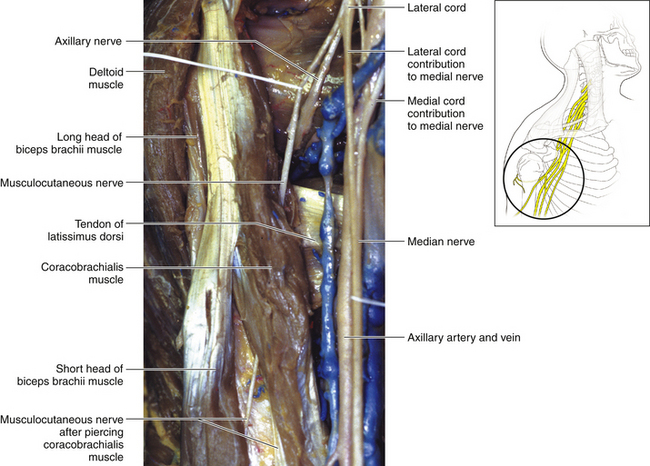

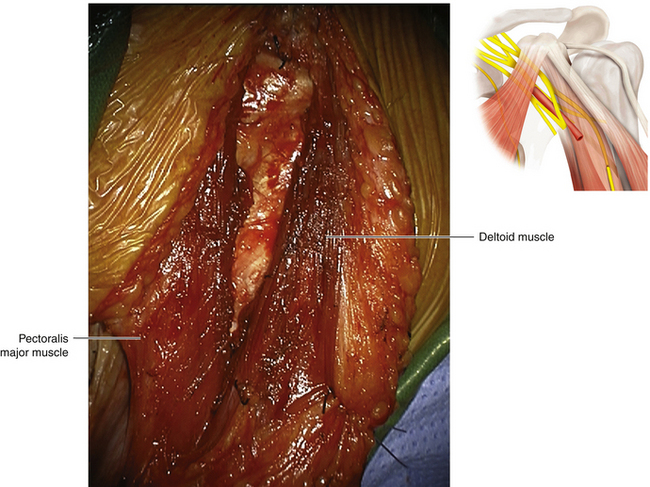

• The infraclavicular brachial plexus exposure usually reveals the lateral cord without difficulty (Figures 9-3 to 9-6). The fascicles of the lateral cord that are destined to form the musculocutaneous nerve may remain stuck inferiorly so that the musculocutaneous nerve may arise from the lateral contribution to the median nerve or from the median nerve itself (i.e., if you cannot find the nerve, look farther distally—it is not absent). In the majority of cases, however, the nerve leaves the lateral cord close to its termination.

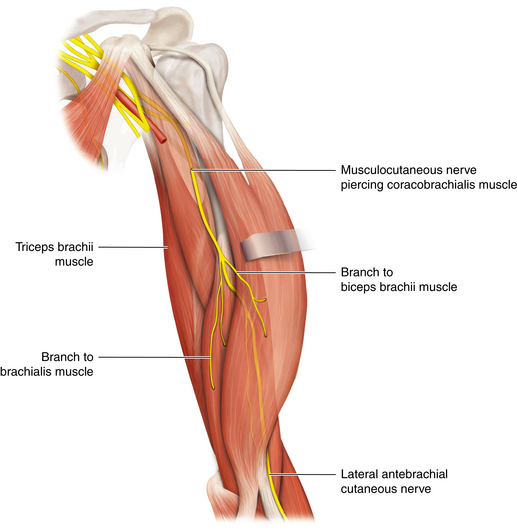

• Small branches are given off to the coracobrachialis, and the main nerve then appears to pierce the coracobrachialis (Figure 9-7).

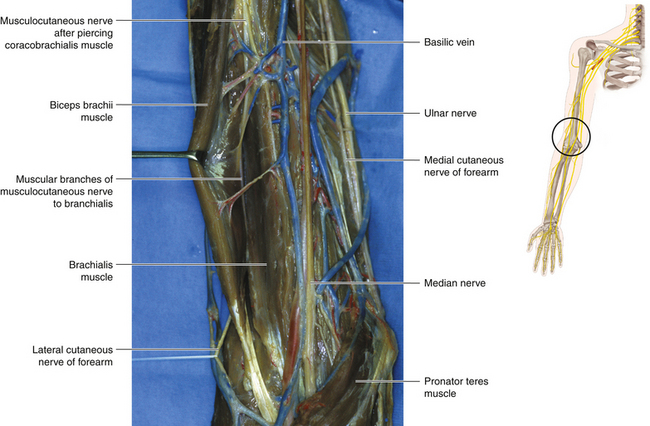

• The nerve runs in the plane between the biceps and brachialis, supplying both, and finally continues as a purely cutaneous nerve (Figure 9-8).

• In stretch injuries, it may be difficult to find viable nerve in the proximal stump. The musculocutaneous fascicles can usually be split away from the lateral cord without injury to either structure. With the surgeon having thus created a proximal stump, grafts can be led from viable tissue.

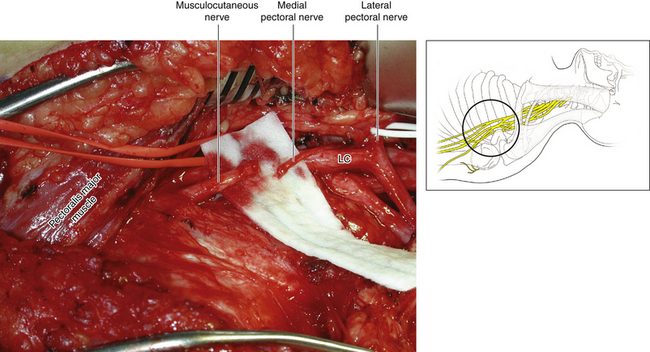

• In the absence of a drive from viable proximal musculocutaneous fascicles, the distal stump can be reinnervated by the medial pectoral nerve, by the intercostal nerves, or by a graft from the C6 spinal nerve (Figure 9-9). These techniques and other tactics are discussed in Chapter 24.

• If there is difficulty finding a viable distal stump, the nerve can be dissected into the plane between the biceps and brachialis; however, there is no point in operating beyond the motor branches to the biceps and brachialis because the object of the operation is to restore elbow flexion (Figures 9-10 and 9-11).

Figure 9-5 The pectoralis major is sharply dissected on its upper border. The cephalic vein is divided.

Figure 9-8 The biceps is retracted to show passage of the musculocutaneous nerve between it and the brachialis.