16 Muscles

Introduction

Muscle weakness is often automatically thought to reflect muscle disease, but that need not be the case. Weak or wasted muscles may result from a lesion anywhere within the nervous system. This starts from the central nervous system (CNS), which produces a typical upper motor neurone (UMN) distribution of weakness. UMN weakness results in the compensatory ‘spastic’ posturing (see Ch 4) consequent to weakness in the antigravity muscles. Damage to lower motor neurones (LMN) will produce weakness in those muscles innervated by the affected LMNs (see Ch 4).

Perhaps the best and most obvious example of how a lesion at different points in the ‘nerve-to-muscle’ relationship can result in a similar picture is reflected in the presentation of ptosis. This may be caused by nerve damage (be it 3rd cranial nerve or autonomic nerve damage), damage at the neuromuscular junction (as seen in myasthenia gravis), or long-standing muscle disease (especially with mitochondrial myopathy) (see Table 16.1).

| Cause | Features |

|---|---|

| 3rd cranial nerve palsy |

There may even be a pseudo-ptosis produced by contralateral facial weakness, which results in a larger contralateral palpable fissure, making the contralateral eye appear larger than the eye with the ‘pseudo-ptosis’. This gives a false impression of ptosis in which the wrong eye is identified as being smaller, rather than the affected eye recognised as being larger (see Table 16.1).

This chapter will not deal with muscle weakness as a consequence of either UMN or LMN lesions, as these have been discussed elsewhere (see Chs 11 and 14). The focus of this chapter will be on pathology at either the neuromuscular junction or more peripherally within the muscle itself. It will be directed to that which is relevant to general practitioners, with the aim of improving clinical acumen and the enjoyment associated with the practice of medicine.

Neuromuscular Junction

a Myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis1 epitomises diseases of the neuromuscular junction, and is an autoimmune disease with antibodies directed against the acetylcholine receptors on skeletal muscles in approximately 90% of those with generalised myasthenia gravis and about half those with ocular myasthenia. Should these antibodies not be identified then the muscle-specific kinase antibodies (MuSK antibodies) are found in about half the remaining patients with myasthenia gravis. Those with MuSK antibodies tend to have a slightly atypical presentation of their myasthenic picture with more oculo-bulbar and neck extensor involvement and more respiratory symptoms.

The usual presentation of myasthenia gravis is with ptosis (see Table 16.1) together with fatiguable muscle weakness, diplopia and possible dysarthria, dysphagia, dyspnoea or fatiguable proximal limb weakness. Almost any skeletal muscle may be involved, as may be respiratory muscles, and myasthenia gravis may mimic other diseases. Purely ocular myasthenia often presents with ptosis and diplopia without other muscle group involvement.

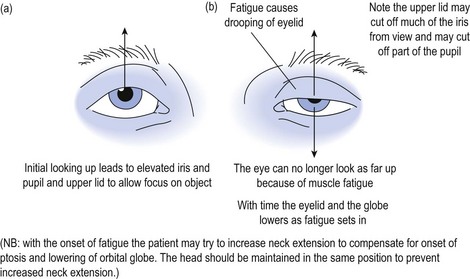

When examining the patient with suspected myasthenia gravis, fatiguability is demonstrated by asking the patient to look up at a fixed object or spot and to maintain the upward gaze (see Fig 16.1).

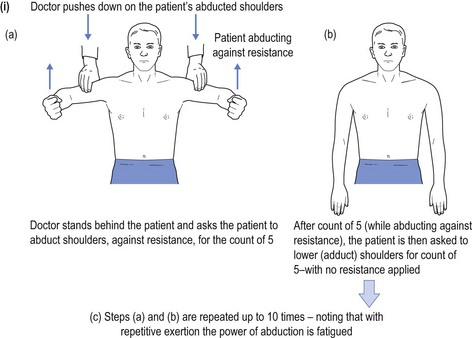

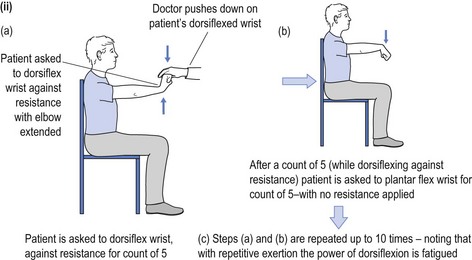

Alternative methods for testing for fatiguability include asking the patient to count aloud to 100, and listening to the quality of articulation to recognise the development of a dysarthric and nasal quality to enunciation as the counting proceeds. Testing muscles of mastication, the patient is asked to bite down on a wooden tongue depressor while at the same time the doctor pulls on the spatula and observes the decline in the strength of the bite. Peripheral muscle fatiguability may be tested by asking the patient to repeatedly perform a muscle task with intervening relaxation, and recording the evolving weakness over time (see Fig 16.2).

FIGURE 16.2 (i) Testing for fatiguability of shoulder abduction; (ii) Testing for fatiguability of wrist dorsiflexion.

What presents as purely ocular myasthenia may often progress to become generalised myasthenia, possibly consequent to an intercurrent infection. As with all neurology, the diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion with the differential diagnosis including: brainstem lesions and other causes of ptosis (see Table 16.1); multiple sclerosis; Graves’ disease (thyrotoxicosis) with ophthalmo-paresis; and other inflammatory myopathies, most of which causes elevation of creatine kinase (CK).

Thymectomy is advocated in young patients with myasthenia (below the age of 50 years) and all those with thymoma. It is not usually advocated in those older than 65 years, those with pure ocular myasthenia or with MuSK antibodies.2

Mestinon® is started at 60 mg b.d. or t.d.s. in mild cases, often complemented with slow release ‘Time Span’ (180 mg) at night. Adverse events may include excess salivation, abdominal cramping and possible diarrhoea; the latter may require anticholinergics. It should be remembered that Mestinon® may exacerbate glaucoma. A cholinergic crisis must be considered in patients with respiratory failure. These patients may also experience dilated pupils, together with the above adverse symptoms plus fasciculations. When this occurs the anticholinesterases should be withdrawn and the patient maintained in an intensive care environment with possible intubation. This represents a medical emergency, which may be provoked following the initiation of Mestinon® therapy.

b Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS)

This is usually a paraneoplastic, auto-immune, myasthenic condition.3 It is caused by antibodies to calcium channels on the presynaptic nerve terminals of skeletal muscles and autonomic ganglia. The myasthenic syndrome usually precedes the diagnosis of the tumour, which is usually a small cell lung cancer.

c Botulism

The toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum blocks the release of acetylcholine from the autonomic and motor nerve endings, causing nausea, vomiting, anorexia, constipation, blurring of vision, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, dyspnoea and limb weakness 12–36 hours after consuming contaminated food.4

Myopathies

As the name implies, ‘myo’ meaning muscle and ‘pathy’ meaning pathology, the focus is now on the end organ, namely the muscles themselves.5 Consideration of muscle diseases may adopt the traditional approach to classification, examining congenital and acquired causes (see Table 16.2).

| Congenital | Acquired |

|---|---|

This produces a long list of disorders, many of which are quite rare and either will not be encountered or will rarely be encountered by general practitioners. Even if encountered by general practitioners, many of the rarer myopathies will be incorrectly diagnosed or overlooked. In many instances the same may be said for the general neurologist who does not practise within the super-sub-specialised area of muscle diseases.

It follows that a very detailed discussion of all these rare myopathies is unwarranted within an overview specifically for general practitioners. This should not be interpreted as being either patronising or derisive of general practitioners, but rather representing a realistic appreciation of the very great demands placed on the average general practitioner. The same might equally apply for the busy general neurologist, who will likewise rely heavily on the input of some specialised colleagues. It is thus incumbent to offer an overview to the approach, acknowledging that the list provided (see Table 16.2) is far from exhaustive.

The fundamental symptoms and signs of myopathy are muscle weakness, both reported by patients and observed when testing power, with/without pain (myalgia). Proximal muscle weakness is more common than is distal weakness, and acute myopathies are usually associated with inflammatory, systemic diseases or toxic aetiology. Slower onset myopathies include the muscular dystrophies and congenital myopathies, mitochondrial myopathies (also congenital although transmitted down the maternal line), metabolic myopathies and muscle membrane channel defects (as evidenced within periodic paralyses and myotonias) (see Table 16.2).

What follows will be a brief discussion of some of the entities in Table 16.2. There will be no attempt to be exhaustive as early involvement of a consultant neurologist is almost universal. The general practitioner provides supportive measures, social interaction and day-to-day symptomatic relief, especially for longstanding disease. The astute general practitioner may offer the initial diagnostic insight, but works in partnership with the consultant. Muscle biopsy requires an even larger therapeutic team in which the physician will suggest which muscle is to be biopsied, the surgeon—usually a neurosurgeon—will conduct the procedure, and the pathologist, armed with adequate history and clinical features, may provide the diagnostic confirmation of the relevant disease process.

Congenital Myopathies

a Muscular dystrophies

These are hereditary diseases6 of which Duchenne and Becker muscular atrophies are most common. Below is a brief overview of some of the congenital myopathies (see Table 16.2).

Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies

Both Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies are X-linked recessive due to mutations in the dystrophin gene (hence sometimes referred to as dystrophinopathies). Duchenne occurs in about 1 in 3500 male births, with Becker having 10% of that incidence (prevalence 1 in 18 000 and 1 in 180 000 respectively). Males are affected while females are carriers. Becker has a similar but milder phenotype to Duchenne, presenting in young adults rather than before the age of 5 years.

b Mitochondrial myopathies

Mitochondrial myopathies7 are inherited via the maternal line and encompass a variety of conditions, including: Kearns-Sayer syndrome (KSS); familial progressive external ophthalmoplegia (PEO); myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibres (MERRF); and encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) with overlap between the various mitochondrial syndromes. Diagnosis and treatment of the mitochondrial myopathies is usually outside the scope of general practice. They have been touched on here purely to whet the appetite, to encourage enthusiastic general practitioners to read further about a relatively new constellation of myopathies.

c Myotonias

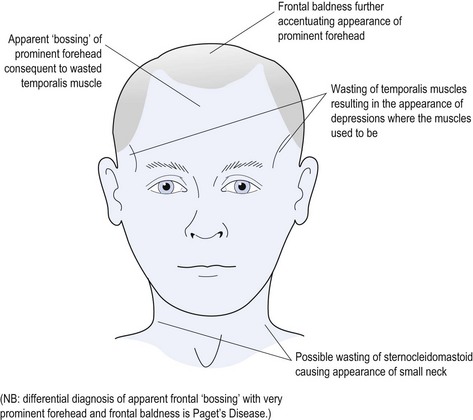

Myotonic dystrophy8 is the most common muscular dystrophy with autosomal dominant, multi-system presentation. It results from a protein kinase gene defect occurring in approximately 1 in 8000 adults. In advanced cases it is often an ‘end-of-the-bed’ diagnosis as it causes obvious wasting of the temporalis muscles, which produces a typical facial appearance (see Fig 16.3).

Features of myotonic dystrophy may include: wasting of the face and neck muscles (particularly temporalis and sternocleidomastoid muscles) (see Fig 16.3); pharyngeal weakness with dysphagia; possible aspiration; conduction cardiac problems (possibly requiring pacemaker); psychological complaints (possibly with impaired intellect, apathy or paranoia); ophthalmic problems with specific cataract formation (in addition to senile cataracts); possible retinal or macular pigmentary degeneration; immunosuppression with low IgG; and hypogonadism (especially in males).

Physical examination may reveal the typical facies (see Fig 16.3) and grip myotonia may be evident when testing hand power—the patient having a problem releasing the tight grip. Often patients with myotonic dystrophy have learnt just how tightly to squeeze before the myotonia is provoked, and may have learned to conceal it. It behoves the clinician to encourage the patient to grip more tightly than the patient initially wants to do, and this may provoke the grip myotonia.

Up to a quarter of infants from affected women will have congenital myotonic dystrophy with mental retardation, respiratory distress, and poor sucking and dysphagia. It is important to warn expectant mothers with myotonic dystrophy of this possibility.

Acquired Myopathies

a Inflammatory myopathies

While uncommon (occurring in about 1 in 100 000), inflammatory myopathies9 have the potential for reversibility so their recognition is imperative. The most common inflammatory myopathies are polymyositis, dermatomyositis and inclusion body myositis. They present with weakness, usually painless, and high CK levels. An exception to this is polymyalgia rheumatica in which there is pain, but CK is usually normal or only slightly elevated while ESR is high.

Dermatomyositis

This presents with a similar picture to polymyositis but is compounded by skin changes, including violaceous heliotrope rash of the eyelids (especially upper eyelids) with erythematous cheeks and malar rash (possibly confused with lupus erythematosus). Knuckles may develop erythematous, scaly macules (grotons papules) with possible further involvement of elbows, knees and upper chest.

b Metabolic myopathies

These include the array of endocrine myopathies,10 such as steroid-induced myopathy associated with 50–80% of patients with Cushing’s disease and 2–20% of patients on long-term steroid therapy. This produces proximal weakness, more so involving the lower limbs than the upper limbs, and may be reduced by using alternate day dosage regimen.

c Electrolyte induced myopathies

Calcium and magnesium changes can also cause myopathy, as may changes in phosphate levels.

d Myopathies associated with drugs and toxins

In addition to alcohol there is a long list of medications that may cause myopathy. These include:

Conclusion

Without doubt, the general practitioner will be the first port of call for the patient with muscle diseases. Once properly empowered, the joy of making the correct diagnosis of what amounts to a relatively rare medical condition cannot be overemphasised. As with the whole ethos of this book, it is hoped that such knowledge will enhance the pleasure of practising medicine. If it achieves that goal then it has benefited both the general practitioners and their patients.

1 Angelini C. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Clinical Drug Investigation. 2011;31(1):1-14.

2 Gomez AM, van den Broeck J, Vrolix K, Janssen SP, Lemmens MA, van der Esch E, et al. Antibody effector mechanisms in myasthenia gravis–pathogenesis at the neuromuscular junction. Autoimmunity. 2010;43(5–6):353-570.

3 Quartel A, Turbeville S, Lounsbury D. Current therapy for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: development of 3,4-diaminopyridine phosphate salt as first-line symptomatic treatment. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2010;26(6):1363-1375.

4 Zhang JC, Sun L, Nie QH. Botulism, where are we now? Clinical Toxicology. 2010;48(9):867-879.

5 Voermans NC, Bonnemann CG, Hamel BC, Jungbluth H, van Engelen BG. Joint hypermobility as a distinctive feature in the differential diagnosis of myopathies. J Neurology. 2009;256(1):13-27.

6 Chandrasekharan K, Martin PT. Genetic defects in muscular dystrophy. Methods in Enzymology. 2010;479:291-322.

7 Hassani A, Horvath R, Chinnery PF. Mitochondrial myopathies: developments in treatment. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2010;23(5):459-465.

8 Lee JE, Cooper TA. Pathogenic mechanisms of myotonic dystrophy. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2009;37(Pt 6):1281-1286.

9 Greenberg SA. Inflammatory myopathies: disease mechanisms. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2009;22(5):516-523.

10 Angelini C, Semplicini C. Metabolic myopathies: the challenge of new treatments. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010;10(3):338-345.