CHAPTER 8 Muscle-Sparing and Free TRAM Flap Breast Reconstruction

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

Breast reconstruction with autologous tissue can generally achieve more durable and natural results than with the use of implants alone.1 When well designed and executed, the TRAM flap offers the advantage of being able to provide large soft tissue volume. In large breasted women undergoing unilateral reconstruction, this technique offers improved aesthetics over implant reconstruction (Fig. 8.1). In addition, complete restoration of the breast mound is often possible in a single stage. Of all the available donor sites for autologous breast reconstruction, the TRAM flap in both pedicled and free form is the most frequently used method.2 The evolution of the TRAM flap, from pedicled, to free TRAM, to muscle-sparing (MS) free TRAM, to perforator flap (DIEP) has occurred in an attempt to reduce the morbidity that results from the loss of the rectus muscle and anterior sheath associated with the pedicled TRAM flap.

The free TRAM flap is based upon the dominant deep inferior epigastric vascular pedicle which permits transfer of a larger volume of abdominal tissue than with the use of pedicled TRAM flaps. The muscle-sparing TRAM flap is a modification of the free TRAM flap which limits the amount of rectus muscle and anterior sheath harvested to only those encompassing the medial and lateral rows of musculocutaneous perforating vessels. The theoretical advantage of the muscle-sparing TRAM is the ability to minimize the violation of the abdominal wall integrity while ensuring equal blood supply to the flap as compared to a free TRAM flap. A more comprehensive understanding of the evolution of the MS TRAM to the DIEP flap is reflected in the classification of muscle-sparing TRAM described by Nahabedien3 (Table 8.1). The DIEP flap is the most refined form of MS TRAM in which no muscle or anterior rectus fascia is harvested with the abdominal flap.

| Muscle-sparing technique | Definition (rectus abdominis) |

|---|---|

| MS0 | Full width, partial length harvested |

| MS1 | Preservation of lateral segment |

| MS2 | Preservation of medial and lateral segments |

| MS3 (DIEP) | Preservation of entire muscle |

From Nahabedian MY, Momen B, Galdino G, Manson PN. Breast reconstruction with the free TRAM or DIEP flap: patient selection, choice of flap, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110(2):466.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

A free or MS TRAM represents an excellent reconstructive option for women undergoing either immediate or delayed breast reconstruction who possess an adequate amount of abdominal fat to achieve the desired breast volume. Moreover, free TRAM or MS TRAM flaps are preferred over pedicled TRAM flaps in the immediate breast reconstruction setting because there is less risk of fat necrosis or partial flap loss in the breast flap. The more dominant blood supply to the free TRAM or MS TRAM can help minimize the problems with wound healing that can lead to delays in the delivery of adjuvant therapy as seen with pedicled TRAMs.4 While obesity and tobacco smoking are two relative contraindications to performing a pedicled TRAM flap, in these high risk patients who either require or strongly desire autologous tissue reconstruction, they generally have a lower complication rate in both the breast and abdomen following a free TRAM or MS TRAM flap.2,4 This is felt to be due to a more robust blood supply to the breast and less surgical insult to the abdominal wall integrity. Lastly, in a large-breasted patient who does not desire a reduction on the contralateral side, a free TRAM or MS TRAM will more reliably transfer a large amount of abdominal tissue onto the chest wall than a pedicled TRAM flap (Box 8.1).

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to free TRAM or MS TRAM include:

Abdominal incisions that should arouse suspicion include those used for inguinal hernia repair and paramedian scars. Conversely, common scars that generally do not preclude the use of free TRAM flaps are lower transverse incisions such as a Pfannensteil incision or midline incisions. The potential lack of recipient vessels should be suspected in patients with both a heavily dissected axilla and radiation to both the chest wall and axilla. Other relative contraindications to free TRAM flaps include patients who are medically unfit, patients with a grave prognosis, and previous liposuction to the abdomen (Box 8.1).

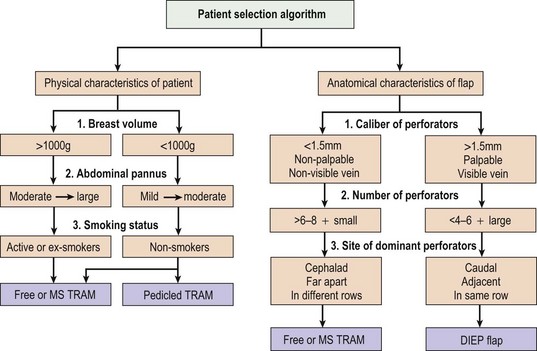

Patient Selection

The choice of which technique of TRAM flap to use is based on the physical characteristics of the patient assessed both preoperative and intraoperatively. An algorithm to aid the decision-making process is outlined in Figure 8.2. Generally, whether the patient is a good candidate for pedicled versus free TRAM can be determined preoperatively based on the physical examination. On the other hand, the decision to use a free TRAM or MS TRAM or DIEP flap is made intraoperatively based on individual anatomical variations.

The role of rectus abdominis muscle within the abdominal flap is to carry and protect the epigastric vascular system.5 The muscle itself is not felt to contribute to volume, shape, or vascularity of the reconstructed breast. MS TRAM minimizes the amount of rectus abdominis muscle and anterior rectus sheath harvested, and thus lessens the insult to the abdominal wall. Though comparative studies examining the incidence of hernias and bulges following pedicled TRAM, free TRAM, and DIEP flaps have shown mixed results, evaluations of abdominal strength have demonstrated that free TRAM is superior to pedicled TRAM, and DIEP flap may be further superior to the free TRAM.6–9 More recently, Nahabedian et al observed a significantly higher incidence of lower abdominal bulges in bilateral breast reconstruction in the non-muscle-sparing than muscle-sparing group.5

The patient characteristics noted preoperatively are as follows:

The anatomical flap characteristics noted intraoperatively are as follows:

Operative Technique

Breast marking

For a patient undergoing skin-sparing mastectomy with a small or moderate sized breast, a simple elliptical or circular excision is marked over the central mound of the breast which includes the nipple–areolar complex (NAC). This allows closure of the reconstructed TRAM flap skin to the mastectomy skin either in an elliptical pattern or as a circular purse-string pattern to create a template for the future NAC (Figs 8.3 and 8.4). For a patient with large breasts or breasts with grade III ptosis, a Wise type pattern skin reduction can be used in the involved breast (Fig. 8.5). For patients with existing grade II ptosis in the involved breast who wish a future mastopexy on the opposite breast, a vertical mastopexy skin excision pattern can be applied.

Abdominal marking

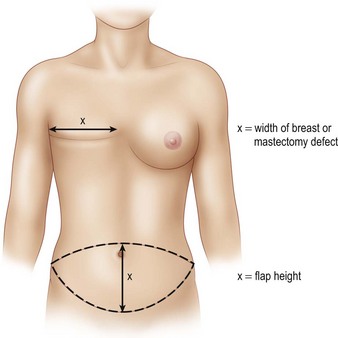

The transverse skin island of the TRAM flap is marked over the lower abdomen encompassing the lower abdominal redundant soft tissues. The superior incision lies just above the level of the umbilicus in order to capture as many periumbilical perforators as possible into the flap (Fig. 8.6). Ideally, the height of the abdominal flap should be equal or greater than the breast width of the mastectomy specimen (Fig. 8.7). This is because during the flap inset, the TRAM flap is inset vertically on the chest as to create the most natural ptotic shape for the reconstructed breast. In designing the inferior incision, care is taken to mark it at a location such that the abdomen can be closed with minimal tension. As well, the inferior incision is designed such that it is hidden in the natural suprapubic crease to camouflage its appearance. Lastly, the inferior incision should not be within the pubic hair-bearing region, as this may lead to problems with delayed wound healing. A midline mark is made just above the umbilicus and on the pubic region. These marks help place the midline of the upper abdominal flap to the midline of the pubic area when closing the abdominal donor site.

Surgical approaches

The free TRAM and MS TRAM technique

1 Flap harvest

At this point, the perforators are visualized carefully under loupe magnification and palpated for pulsations to decide between performing a MS TRAM versus a DIEP flap (see Fig. 8.2). Before committing to free muscle transfer or transecting the superior aspect of the rectus muscle, recipient vessels must be completely dissected to ensure usability of both a vein and an artery.

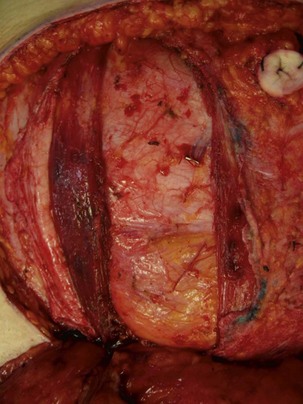

Free MS TRAM

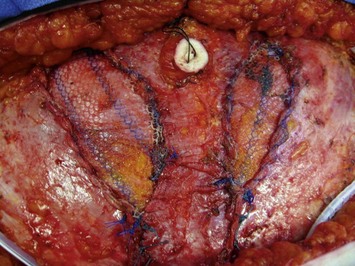

If both the medial and lateral rows of perforators are selected, then the medial anterior rectus sheath incision is made first using cautery on a cutting setting. The rectus muscle is then bluntly dissected medial to the medial row perforators taking care not to cause accidental tearing of any small branches. Intramuscular dissection is carried inferiorly using bipolar cautery to split the rectus muscle and retain the medial branch of the pedicle with the elevated rectus muscle. Although this medial strip of muscle may or may not be innervated, it is believed to help with the final results obtained at the abdominal donor site.12

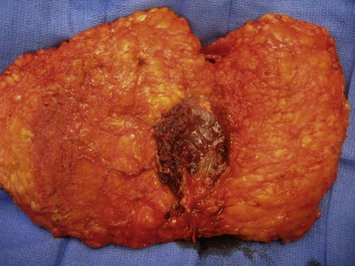

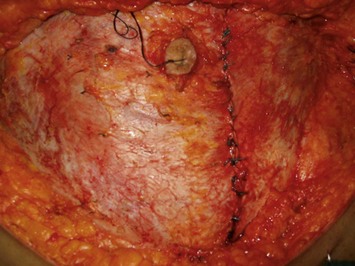

The fascial and muscle-sparing flap is then elevated from cranial to caudal in a routine fashion. Intramuscular dissection is continued carefully until the deep inferior epigastric vessel is identified at its entry into the lateral aspect of the muscle. Once the pedicle is identified deep to the transversalis fascia, the inferior aspect of the muscle is transected using electrocautery while protecting the pedicle. The above completes the description of a type II MS TRAM (Figs 8.8 and 8.9).

2 Recipient vessel dissection

Dissection of the internal mammary vessels

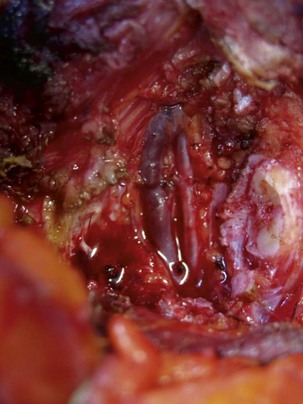

The internal mammary vessels are dissected in the entire course of the rib interspace to ensure adequate exposure during vessel anastomosis (Fig. 8.10) It is important to allow sufficient time for these fragile vessels to rest and rewarm in order to reach maximum vasodilation.14

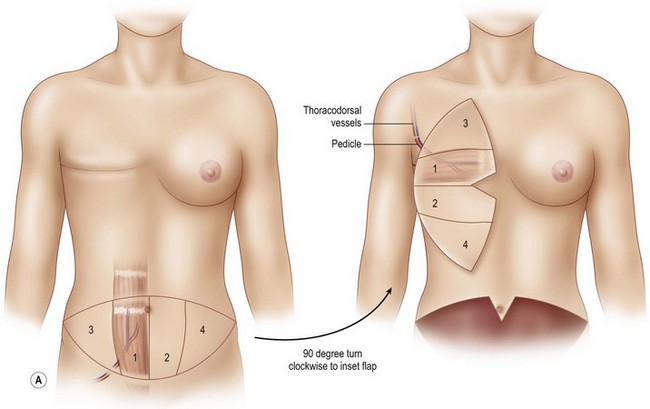

Dissection of the thoracodorsal vessel

In the setting of immediate reconstruction, the recipient thoracodorsal vessels are usually well exposed following axillary dissection, and if kept free from injury and spasm, they are the best choice for recipient vessels.15 If a skin-sparing mastectomy is performed through a small periareolar incision, then a separate incision in the axillary dome is necessary for dissection of the thoracodorsal vessels (Fig. 8.11). For delayed reconstructions, many surgeons avoid dissecting in the previously radiated or dissected axilla. This exploratory process is inherently difficult when the thoracodorsal vessels are encased in scar and the vessels are often too fibrosed to be used safely after significant wasted time and effort.

3 Anastomosis

Setup for anastomosing to the internal mammary vessels

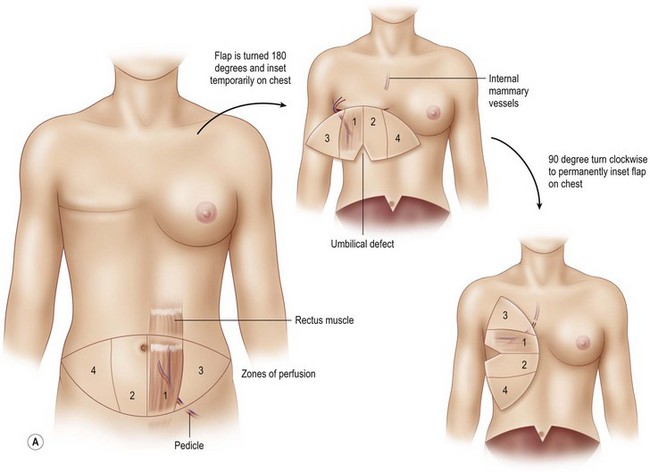

The flap is rotated 180° and set down on the chest in a horizontal fashion such that the pedicle is exiting from the superior border of the flap and the umbilical defect of the flap is at the inferior border of the flap (Fig. 8.12). This orientation of the flap allows for microanastomosis between the donor and recipient vessels to take place without twisting or kinking. Once the position of the flap is set, the sponge containing the flap is stapled to the chest skin to stabilize the flap during the anastomosis.

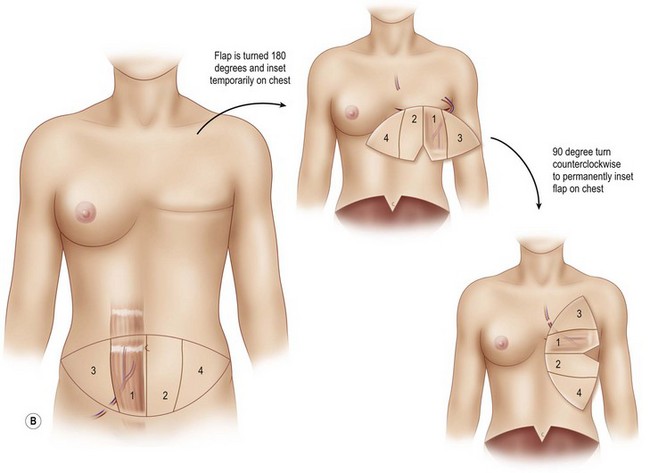

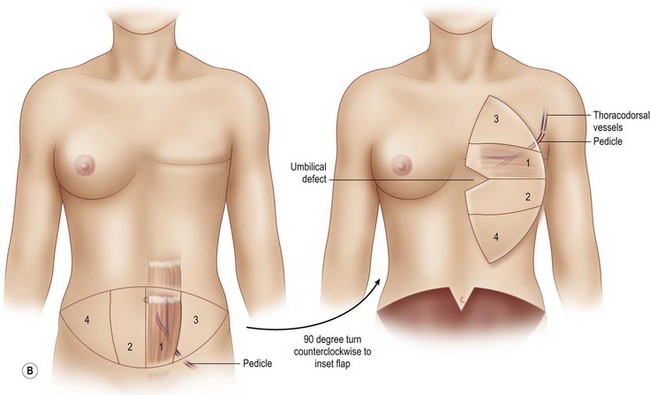

Setup for anastomosing to the thoracodorsal vessels

The flap is rotated 90° and set down on the chest in a vertical orientation such that the ipsilateral tip of the flap is directed at the clavicle and the contralateral tip of the flap is directed at the feet (Fig. 8.13). The pedicle exits obliquely from the flap and reaches the thoracodorsal vessels with a gentle curve. The flap is similarly secured to the chest skin as described above.

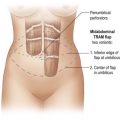

4 Abdominal wall closure

In a unilateral MS TRAM, the fascial defect is always closed primarily using interrupted 0-Ethibond sutures at 2 cm intervals and over-sewn with 2-0 running PDS suture (Fig. 8.14). Emphasis is made on closing both leaflets of the anterior rectus sheath, as this has been shown to reduce bulge rates.9 A contralateral plication of the anterior abdominal sheath is performed in selected cases to centralize the umbilicus and give balance to the abdominal wall closure.

In some cases of bilateral MS- or free TRAMs, a small mesh inlay may be necessary. The fascial defect is repaired with a soft polypropylene inlay mesh using interrupted 0 polypropylene sutures. The size of the mesh is tailored to exactly replace the amount of fascia harvested with the flap (Fig. 8.15). The patient is then put into a semi-fowler’s position to take the tension off the abdominal skin during skin closure. The upper abdominal skin flap is advanced and sutured to the lower abdominal flap using multi-layered closure over two closed suction drains. A new umbilical opening is made using a small vertical elliptical excision on the abdominal wall and the umbilicus is retrieved and closed at its new position. In a younger and thinner patient, creation of some superior hooding of the umbilicus is advantageous. With the abdomen closed, the patient can now be placed in an upright position in the bed and flap inset can take place.

5 Flap inset

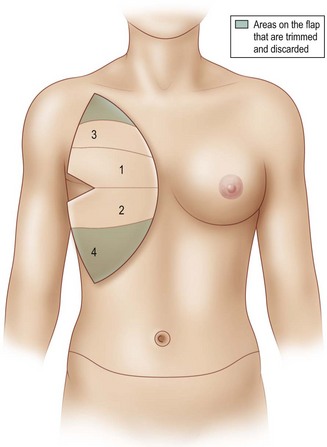

Once the mastectomy pocket is adequately developed, the TRAM flap can be tacked in place to shape the breast mound. The TRAM flap that is anastomosed to the internal mammary vessels must now be rotated another 90° such that Zone III is now directed at the clavicle and Zone IV is directed at the feet (Fig. 8.12) When the pedicle is anastomosed to the thoracodorsal vessels, the flap has already assumed a vertical position on the chest, therefore no additional flap rotation is necessary for the final inset (Fig. 8.13). In a unilateral breast inset, the corner of Zone III is trimmed and then tucked under the superior mastectomy flap to add superior pole fullness and minimize any superior hollowing. Zone IV is completely amputated and Zone II is trimmed to match the volume of the reconstructed breast to the opposite breast (Fig. 8.16).

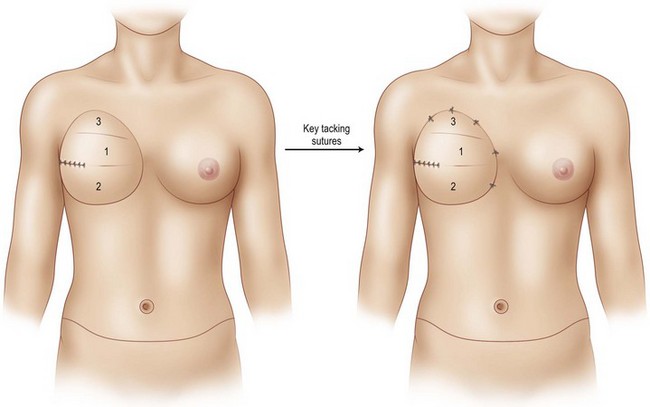

Tacking sutures are then used to secure the flap to the chest wall with interrupted 2-0 Vicryl sutures. When insetting the TRAM flap, the first and most important tacking suture is at the most superomedial aspect of the breast mound (Fig. 8.17). Tacking sutures are then placed along the sternal border to ensure a medial flap inset position, and these are followed by superior tacking sutures to create an upper breast pole. Superolaterally, the TRAM flap should be sutured to the remaining soft tissues anterior to the axillary fold to avoid an unsightly dysjunction between the axilla and breast. These insetting sutures are important to obtain and maintain breast mound shape. Over-zealous use of these shaping sutures, however, must be avoided as fat necrosis can result beneath these sutures. Controlling the lateral aspect of the TRAM flap can help to increase breast projection by the use of sutures to effectively roll the lateral TRAM tissue under itself (Fig. 8.18). The inferior pole of the breast is simply folded and tucked above the recreated IMF to create a natural ptotic breast.

In the setting of delayed reconstruction, particularly with radiation-induced changes present, the skin envelope can be very poor in quality and relatively inelastic. We address this by replacing the inelastic and damaged skin flaps with as much TRAM skin island as possible (Fig. 8.19). In order to adequately fit the TRAM flap under a tight upper mastectomy skin flap, several vertical-releasing incisions can be used in the superior mastectomy flap to release the constriction band in the junction between the mastectomy flap and TRAM flap. When relaxing incisions are not made at the time of the primary surgery, the tight band between the mastectomy flap and TRAM flap does not settle or become subtle over time (Fig. 8.20).

Summary of the operative steps for unilateral MS TRAM

1 MS TRAM harvest

2 Recipient vessel dissection

3 Vessel anastomosis

4 Abdomen closure

5 Breast inset

Pitfalls and How to Correct

Case I: Vessel thrombosis

Case II: Medial and superior hollowness of the reconstructed breast

When preparing the mastectomy pocket prior to inset of the TRAM, the inframammary fold must be inspected. If it has been violated, the fold must be recreated using permanent sutures. An IMF that is obliterated or poorly defined is unsightly and unnatural in its appearance (Fig. 8.22). It is advisable to create the IMF in the primary setting rather than during revisions.

During the inset of the TRAM, a common mistake is failure to secure the TRAM flap sufficiently superior and medial within the mastectomy defect. Figure 8.23 illustrates a suboptimal aesthetic result of a TRAM reconstructed breast. The patient is dissatisfied with the medial and superior hollowness of the breast (Fig. 8.23).

To avoid this pitfall, the first and most important tacking suture is at the most superior-medial pole of the breast mound (see Fig. 8.17). The most difficult revisions of the reconstructed breast mound involve transposing the entire breast mound more medially and superiorly. Therefore this key suture must place the TRAM flap in the mastectomy pocket that is adequately medial and superior from the onset. The next tacking sutures that follow are along the sternal border to ensure a medial flap inset position to provide medial breast volume and desirable cleavage. Superior tacking sutures are then placed with attention directed at creating upper pole fullness that may appear slightly exaggerated at the time of the OR. Superolaterally, the TRAM flap is tacked to the remaining soft tissue anterior to the axillary fold. As all autologous tissue reconstructed breasts descend over time, if this step is not performed, an unsightly disjunction will appear between the axilla and breast (Fig. 8.24).

Case III: Delayed mastectomy flap necrosis around the TRAM flap

Significant mastectomy flap necrosis around the TRAM flap will result in weeks of dressing changes, psychological distress and delay in adjuvant therapy for the patient. The final reconstructive result will be suboptimal with a distorted breast envelope and a widened or hypertrophic scar. Figure 8.25 illustrates significant mastectomy flap necrosis following a free MS TRAM in an immediate breast reconstruction (Fig. 8.25).

The risk of mastectomy flap necrosis is greater when a Wise-pattern skin reduction pattern incision is used. It is important to limit this type of skin reduction pattern to situations where an experienced breast surgeon is involved who can provide dependable vascularity to these mastectomy flaps.12 This type of skin design should not be attempted if a previous lumpectomy or core biopsy incision is located on the upper mastectomy skin flaps that restricts superiorly based blood supply in the already challenged mastectomy flaps.

In the case of immediate reconstruction, viability of the mastectomy flaps must be carefully assessed. Any questionable areas of vascularity on the mastectomy flap are removed and replaced with healthy TRAM skin during breast inset. Assessment of mastectomy flap viability is particularly challenging in dark skinned women (Fig. 8.26). In such a scenario or when there is a significant area of possible vascular compromise of the mastectomy flap, then the TRAM flap can be buried under the mastectomy flap with the skin loosely secured. At a second stage 5 to 7 days later after the mastectomy flap has had sufficient time to demarcate, the patient can be brought back to the OR for definitive mastectomy flap trimming and TRAM flap skin island inset.

1 Clough K, O’Donoghue J, Fitoussi A, et al. Prospective evaluation of late cosmetic results following breast reconstruction. II: TRAM flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1710-1716.

2 Beckenstein MS, Grotting JC. Breast reconstruction with free-tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1345.

3 Nahabedian MY, Momen B, Galdino G, Manson PN. Breast reconstruction with the free TRAM or DIEP flap: Patient selection, choice of flap, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:466.

4 Schusterman MA. The free TRAM flap. In Breast reconstruction with autologous tissue. Clin Plast Surg. 1998:191.

5 Nahabedian MY, Dooley W, Singh N, Manson PN. Contour abnormalities of the abdomen after breast reconstruction with abdominal flaps: the role of muscle preservation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:91.

6 Arnaz ZM, Zahn U, Pogorelec D, Planinsek F. Rational selection of flaps from the abdomen in breast reconstruction to reduce donor site morbidity. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:351.

7 Blondeel PN. One hundred free DIEP flap breast reconstructions: a personal experience. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:104.

8 Edsander-Nord A, Jurell G, Wickman M. Donor site morbidity after pedicled or free TRAM flap surgery: a prospective and objective study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1508.

9 Kroll SS, Schusterman MA, Reece GP, Miller MJ, Robb G, Evans G. Abdominal wall strength, bulging, hernia after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:616.

10 Hamdi M, Weiler-Mithoff EM, Webster MH. Deep inferior epigastric perforator flap in breast reconstruction: experience with first 50 flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:86.

11 Serafin D. Chapter 24: The rectus abdominis flap. Atlas of microsurgical composite tissue transplantation. New York: Elsevier Science; 1996.

12 Serletti JM. Breast reconstruction with the TRAM flap: pedicled and free. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:532.

13 Temple CL, Strom EA, Youseef A, Langstein HN. Choice of recipient vessels in delayed TRAM flap reconstruction after radiotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):105.

14 Ninkovic MM, Schwabegger AH, Anderl H. Internal mammary vessels as a recipient site. In Breast reconstruction with autologous tissue. Clin Plast Surg. 213, 1998.

15 Robb GL. Thoracodorsal vessels as a recipient site. In Breast reconstruction with autologous tissue. Clin Plast Surg. 207, 1998.