Multiple sclerosis II

Differential diagnosis

Single episodes

Spinal cord syndromes

The most important differential diagnosis is spinal cord compression (Fig. 1a). In more insidious spinal cord syndromes, the differential diagnosis includes rarer spinal cord disease such as vitamin B12 deficiency, HTLV-1 myelopathy and familial spastic paraparesis. In patients lacking sensory signs, consider amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; associated lower motor neurone signs allow a distinction. After first presentation with complete transverse myelitis, patients later develop MS; those with partial spinal cord syndromes more often progress (70%).

Investigations

The investigation of a patient with suspected MS can be divided into:

Finding characteristic abnormalities

Demonstrating clinically silent lesions

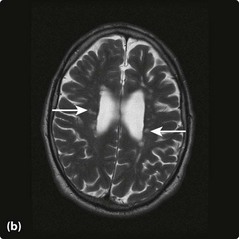

MRI is particularly powerful at detecting clinically silent lesions in MS. These tend to occur in characteristic sites within the white matter: the periventricular region and corpus callosum (see Fig. 1). Similar changes can be seen in the spinal cord, though these are more commonly found when symptomatic. If a scan is enhanced with gadolinium, then active lesions can be seen; the enhancement persists for 6–8 weeks.

Finding characteristic CSF changes

Routine analysis of the CSF usually produces a normal result: the white cell count may be slightly elevated (<15 cells/ml). Protein electrophoresis, using isoelectric focusing, may find oligoclonal bands (OBs) in the CSF but not in serum. This indicates intrathecal immunoglobulin synthesis and is present in 95% of patients with clinically definite MS. OBs occur in other diseases, infections (e.g. neurosyphilis, Lyme disease) and in inflammatory diseases (e.g. Behçet’s syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus), but in these systemic illnesses the same bands are usually also found in serum.

Complications

The complications of MS have much in common with other disabling neurological conditions. Common medical problems seen in MS are summarized in Table 1. The social impact of the disease can include loss of job, divorce or social isolation. Depression is common and suicide can occur.

| Problem | Treatments | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Spasticity | Baclofen, dantrolene, tizanidine, physiotherapy, botulinum toxin in selected muscles | Reducing the tone with drugs must be balanced against the increased weakness |

| Fatigue | Amantadine, pemoline, modafinil | N.B. Fatigue may be a symptom of depression |

| Ataxia | Isoniazid (with pyridoxine) | Usually there is little response |

| Bladder problems | ||

| Unstable bladder Uncoordinated bladder | Oxybutynin, tolterodineIntermittent self-catheterization ± oxybutynin | Consider urinary infection and treat |

| Erectile failure | Sildenafil | |

| Constipation | Bulking agents and stool softeners | May need manual evacuation |

Management and treatment

Treatment

Symptomatic treatment

Specific symptoms can be helped. The most common problems are summarized in Table 1. Pain may occur and usually responds to pain-modulating drugs such as amitriptyline or gabapentin. Carbamazepine may also help some paroxysmal symptoms such as Lhermitte’s or trigeminal neuralgia. Tremor is usually difficult to treat; occasionally stereotactic thalamotomy may be helpful. Depression is common and needs to be treated with appropriate support and antidepressants. Physiotherapy is helpful at optimizing the level of function of the patient and occupational therapy optimizes the patient’s environment to minimize the impact of disabilities. Speech therapy may be helpful in some patients.

Disease-modifying treatments

Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody affecting permeability of the blood–brain barrier. It has a greater effect on relapse rate than beta-interferon, but a small risk of developing fatal progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (p. 101) means it is licensed in the UK for only a small proportion of patients with aggressive disease.