60 Multiple sclerosis

Patient 2

Salient features

Examination

• Spastic paraparesis (increased tone, upgoing plantars, weakness, brisk reflexes and ankle or patellar clonus). Spasticity is quantified using the Ashworth scale, which scores muscle tone on a scale of 0–4 with 0 representing normal tone and 4 severe spasticity

• Impaired coordination on heel–shin test (if there is marked weakness, this test may be unreliable).

• Check abdominal reflexes (absent or diminished in over 80% of cases)

• Tell the examiner that you would like to look for optic atrophy and cerebellar signs.

Questions

What investigations would you consider?

• Spinal radiography, including both cervical and thoracic regions

• Lumbar puncture: total protein concentration may be raised (in 60% of cases), with an increase in the level of immunoglobulin G (in 40%) and oligoclonal bands (in 80%) on electrophoresis

• Visual evoked potentials: despite normal visual function, there may be prolonged latency in cortical response to a pattern stimulus. This indicates a delay in conduction in the visual pathways

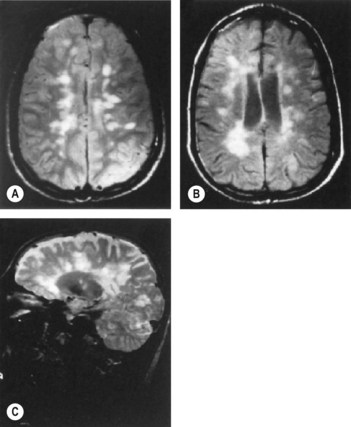

• MRI of brain: about 50% of patients with early multiple sclerosis in the spinal cord show abnormal areas in the periventricular white matter

• Serum vitamin B12 to exclude subacute degeneration of the spinal cord.

Advanced-level questions

What are the clinical categories of multiple sclerosis?

• Relapsing-remitting: episodes of acute worsening with recovery and a stable course between relapses

• Secondary progressive: gradual neurologic deterioration with or without superimposed acute relapses in a patient who previously had relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis

• Primary progressive: gradual, nearly continuous neurologic deterioration from the onset of symptoms

• Progressive relapsing: gradual neurologic deterioration from the onset of symptoms but with subsquent superimposed relapses.

Do you know of any criteria for diagnosis of multiple sclerosis?

The revised McDonald’s criteria are based on the clinical attacks and lesions initially, attempting to establish dissemination in time (have occurred at least 30 days apart) and place (affecting separate sites within the CNS) for lesions (Ann Neurol 2005;58:840–6, Lancet 2008; 372:1502–17). If the clinical features do not fit the criteria exactly, MRI can substitute for one of these clinical episodes (Fig. 60.1): MR lesions are defined as occurring with:

• dissemination in time: one gadolinium-enhancing lesion at least 3 months after the onset of the clinical event or a new lesion identified by T2-weighted imaging compared with a reference scan done at least 30 days after onset of the clinical event

Which conditions may be considered forme fruste of multiple sclerosis?

Mention some other demyelinating disorders

• Devic’s disease: optic neuritis with acute myelitis with MRI changes that extend over at least three segments of the spinal cord. It is associated with a specific antibody marker (NMO-IgG) targeting the water channel aquaphorin-4 (Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2008;8:427–33)

• Tuberous sclerosis (patchy demyelination; see p. 690)

• Schilder’s disease (diffuse cerebral sclerosis; may present with cortical blindness when the occipital cortex is involved).

What are the prognostic markers that predict more severe multiple sclerosis?

What is the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis?

• Disorders affecting one anatomical site and with either a relapsing–remitting or progressive course (especially, tumours and other structural lesions)

• Monophasic disorders affecting several neuroantaomical locations (e.g. acute disseminated encephalomyelitis)

• Diseases of the spinal cord and brain confined to selected physiological systems and usually following a progressive course (e.g. the hereditary cerebellar ataxias)

• Non-organic symptoms that, intentionally or otherwise, mimic the clinical features of multiple sclerosis (so-called functional or somatization disorders).

Is there any treatment for multiple sclerosis?

Immunomodulatory agents/approaches

• Two forms of interferon-β (i.e. interferon beta-1b (Betaferon) and interferon beta-1a (Avonex, Rebif)) have been shown to reduce the relapse rate in relapsing–remitting (non-progressive) neurological deficit by one-third (Neurology 1993;43:655–67, Lancet 1998;352;1491–7). Whether reduction in relapse rate reduces or prevents later disability is not known; some evidence has been presented in favour. The Association of British Neurologists recommends interferon-β be prescribed for ambulant patients with at least two definite relapses in the previous 2 years followed by recovery (may or may not be complete).

• Interferon beta-1b has been reported to delay progression (for 9–12 months in a study period of 2–3 years) in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis of moderate severity (minimum walking distance of 20 m with assistance) and has been licensed for this indication. However, the SPECTRIMS study, which was a large trial, showed no significant benefit of interferon-1b therapy in delaying disability in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

• Intravenous methylprednisolone may hasten recovery from acute relapses but has no effect in the long term. A recent trial suggested intravenous methylprednisolone is no better than equivalent oral doses of methylprednisolone for acute relapses (Lancet 1997;349:902–6).

• Copolymer-1 (Neurology 1995;45:1268–76), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) and pulsed intravenous immunoglobulin (Lancet 1997;349:589–93) like interferon-β, reduce the relapse rate. However, the role of immunomodulatory agents needs to be defined.

• Plasma exchange enhances recovery of relapse-related neurologic deficits in patients with no response to high-dose corticosteroids.

• Newer therapies: two oral agents, cladribine and fingolimod, have been used in the treatment of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Both reduce the number of potentially autoaggressive lymphocytes that are available to enter the central nervous system (CNS). Cladribine (in the CLARITY trial) and fingolimod (in the FREEDOMS trial) were highly effective against placebo over a 2-year period, and fingolimod was more effective than intramuscular interferon beta-1a over a 12-month period (in the TRANSFORMS trial).

• Alemtuzumab was more effective than interferon beta-1a in early, relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis but was associated with autoimmunity, most seriously manifesting as immune thrombocytopenic purpura (N Engl J Med 2008;359:1786–1801).

• A single course of rituximab (by depleting B cells) reduces inflammatory brain lesions and clinical relapses for 48 weeks (N Engl J Med 2008;358:676–88).

Miscellaneous

• Fatigue is modestly reduced by amantadine (Neurology 1995;45:1956–61).

• Bladder dysfunction usually consists of combined detrusor hyper-reflexia and incomplete emptying volumes, with <100 ml urine remaining in the bladder after micturition, is managed with oxybutinin or detrusitol; retention of volumes >100 ml require clean, intermittent self-catheterization (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:6–13).

• Sexual dysfunction (erectile failure) may be helped with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor sildenafil citrate (Viagra), yohimbine or other alpha-adrenergic blockers.

• Limb spasticity requires a multidisciplinary approach ensuring correct posture, prevention of skin ulceration from pressure, management of bladder and bowel dysfunction as well medications such as tizanidine (an α2-adrenoreceptor antagonist) an antispastic agent (Neurology 1994;44(suppl 9):70S–8). Tizandine reduces spasticity but there is no beneficial effect on mobility.