10 Multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Even the understanding of the basic pathophysiology of MS has changed enormously over the last decade. It used to be thought that MS was purely a white T-cell autoimmune demyelinating central nervous system (CNS) disease. More recently, the immunological role of B-lymphocytes in the evolution of MS has been appreciated, as has the major contribution of the associated axonal degeneration that causes shrinkage of the brain volume. To better understand the concept of demyelination contrasted with axonal degeneration, the reader is referred to Chapter 11 on peripheral neuropathy in which the issues are discussed in depth. The basic concepts remain the same although the location is the central rather than the peripheral nervous system.

One reason MS is feared is that it is an unpredictable disease with exacerbations and remissions. It is a disease in which lesions occur within the CNS that are ‘separated in time and place’. The diagnostic criteria for MS have also been modified with the international acceptance of the ‘McDonald criteria’ (see Table 10.1).

These criteria acknowledge the role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis of MS. The criteria, formulated by a panel of experts chaired by McDonald, recognised that MS may be identified by clinical symptoms and signs, MRI detected lesions (that may occur without associated clinical features) and the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) that herald CSF immunological insult.1

The easier access to MRI has produced a practical recognition that for every clinically identified ‘attack’ of MS, there may be as many as six to ten sub-clinical ‘attacks’ that would remain silent were it not for the MRI trademark of the MS plaque.

There is a variety of types of MS, and it is accepted that not all types respond equally to accepted MS treatment. Use of disease modifying agents, such as the interferons or glatiramer acetate, requires a diagnosis of MS confirmed by MRI2 (the date of that MRI being part of the prescription approval process), but these agents are not available to patients with advanced disability (unable to walk more than 100 metres without assistance). This is equivalent to the disability rating of 6.0 on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)3 (see Table 10.2).

| EDSS score | Description | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | Normal neurological functioning | Able to partake in regular activities |

| 1.0 | Minimal impairment in one functional system but essentially normal | |

| 1.5 | Minimal impairment in more than one functional system but essentially normal | |

| 2.0 | One functional system with minimal disability | |

| 2.5 | Two functional systems with minimal disability | |

| 3.0 | One functional system with moderate disability or minimal disability in three or four | |

| 3.5 | No problems walking but with moderate disability in one functional system plus mild disability in two or more functional systems | Moderate impairment in daily functions |

| 4.0 | No problems walking without aid for 500 m but severe impairment in one functional system or combinations of mild to moderate impairments in multiple functional systems | |

| 4.5 | No problems walking without aid for 300 m but severe impairment in one functional system or combinations of mild to moderate impairments in multiple functional systems | |

| 5.0 | Cannot walk more than 200 m without aid and unable to complete a full day of activities without impairment | Unable to complete all daily activities |

| 5.5 | Cannot walk more than 100 m without aid and unable to complete a full day of activities without impairment | |

| 6.0 | Requires unilateral assistance to walk 100 m | Needs ambulatory assistance |

| 6.5 | Requires bilateral assistance to walk 100 m | |

| 7.0 | Unable to walk 5 m even with bilateral assistance, restricted to a wheelchair | Mostly restricted to a wheelchair |

| 7.5 | Unable to take two steps even with bilateral assistance, restricted to a wheelchair | |

| 8.0 | Arms still effective, confined to wheelchair or bed | |

| 8.5 | Arms have some functioning, confined to bed | Bedridden |

| 9.0 | Arms not functional, can communicate and eat | |

| 9.5 | Cannot communicate or eat effectively | |

| 10.0 | Death due to MS | Death |

Diagnosing MS

If the place of birth is further from the equator, migration after the age of 15 years means one brings the prevalence of MS of the place of origin to the destination rather than assuming the prevalence appropriate to the destination. Within the Australian context, the incidence of MS is sixfold greater in Tasmania than in northern Queensland. Some argue that this relates to an increased exposure to sunlight and vitamin D, which occurs closer to the equator, but the absolute answer remains unclear. If one parent has MS there is a 1–2% chance of the child having MS and, if a monozygotic twin has MS, then the chance of the sibling twin developing MS is of the order of 35%. There is a suspicion of an association between MS and previous infection with the Epstein-Barr (EB) virus. It follows that there is a variety of red flags that should alert the general practitioner to the possibility of MS.4

Because the presentation of MS can be so varied, it is most important, especially when assessing young women, not to dismiss symptoms that are difficult to understand. If it is possible for the symptoms to emanate from the CNS, then the diagnosis of MS should be entertained. As a rule of thumb, the diagnosis of MS is beyond the scope of the average general practitioner. It requires lumbar puncture, looking for oligoclonal bands; evoked potential studies (including visual, somatosensory and possibly brainstem) looking for lesions that are separated in place (located within the CNS); as well as the MRI. Despite general practitioners now having greater access to MRI, in reality, to diagnose MS most general practitioners will refer the patient to a consultant before ordering an MRI. Another reason for early referral is that there is good evidence to suggest that the earlier treatment is instigated, the better is the outcome.2 A number of companies are now offering special compassionate access to disease modifying drugs for patients with Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS)—for patients having experienced a single attack without meeting the criteria for a definitive diagnosis of MS—to ensure the earliest possible availability of treatment. This further recognises the merit of early intervention on long-term prognosis.

As stated in other chapters, it is far more intellectually rewarding for the general practitioner to refer the patient to the consultant with a confirmed and correct provisional diagnosis, so the family doctor needs to be aware of the symptoms of MS to take an appropriate history (see Table 10.3).

| Symptoms | Signs | |

|---|---|---|

| Optic neuritis |

Types of MS

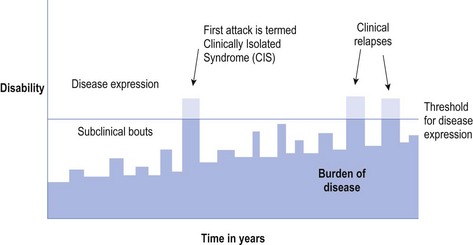

Of the variety of types of MS, the most common is relapsing remitting MS (RRMS) that occurs in approximately 85% of MS at the onset of the disease and about 60% of the total MS population.4 Patients with RRMS may have subclinical episodes preceding and following a clinical ‘attack’ (see Fig 10.1).

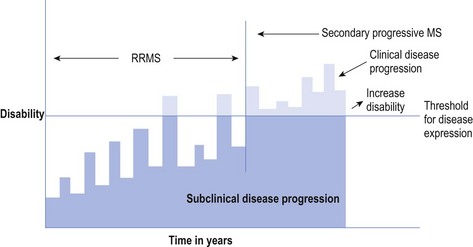

Once the relapses combined with the burden of disease surpass the threshold for clinical disease expression on a more permanent basis, the RRMS enters the secondary progressive phase, known as secondary progressive MS (SPMS). The patient never returns to a subclinical status (see Fig 10.2). This accounts for approximately 20% of all people with MS.

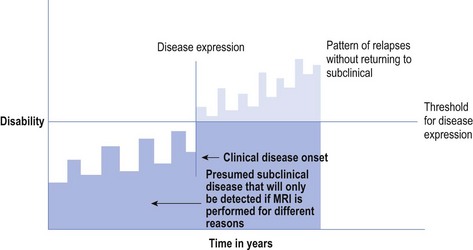

About 5% of all MS patients are said to have progressive relapsing MS (PRMS) in which they never really return to a subclinical status below the threshold of a disease expression, and the disease continues relentlessly. They do have bouts of increased disease expression, which constitute relapses, from which they do improve, but the burden of disease increases and is cumulative (see Fig 10.3).

In one form of primary progressive MS (PPMS) there appears to be a linear progression of disease from the outset, without apparent relapses and remissions, without the patient returning to a subclinical state, with constant expression of disease (above the threshold of disease expression). PPMS more commonly includes spinal involvement and appears to affect a somewhat older population at onset (30s and 40s at onset). This is also said to occur in approximately 5% of all MS patients and 10% at the onset of disease.

A form of possible MS known as Devic’s disease, also known as neuro myelitis optica (NMO), appears to affect a somewhat different population, being more common among Occidental people. It is less responsive to currently available remedies. There remains an argument as to whether NMO is actually part of the MS spectrum or is a completely different disease entity with specific involvement of the spinal cord and optic pathway.5 For the purpose of this discussion such debate is irrelevant and remains the precinct of specialists, as the patient will have been referred for a consultative opinion prior to diagnosis of NMO. What is worth noting is that there is an NMO antibody, also called aquaporin3, that is measurable in NMO patients.

Symptoms and Signs of MS

As MS is a disease of relapses and remissions, it is important to appreciate that a relapse is classically defined as the onset of new symptoms or the exacerbation of existing symptoms that last for at least 48 hours, and are often called ‘attacks’. Such exacerbations represent an episode of demyelination: what occurs within the relapse is defined by the site, be it in the cerebral hemispheres (affecting cognition, emotions, motor activity or sensation); brainstem (possibly affecting cranial nerves or their interconnections); or the cerebellum (affecting coordination). It is accepted that MS can also cause demyelination within the spinal cord and, again, its expression is determined by the site within the cord and the pathways affected (see Tables 10.2 and 10.3). As touched upon above, in the condition known as NMO demyelination is restricted to the optic pathways and the spinal cord. One of the hallmark features of NMO is that the spinal cord involvement is much longer, covering a number of vertebral segments, than is usually encountered in other forms of MS. As indicated above, aquaporin3, also called NMO-antibody, can be measured in the blood and/or CSF of the patient with NMO.6

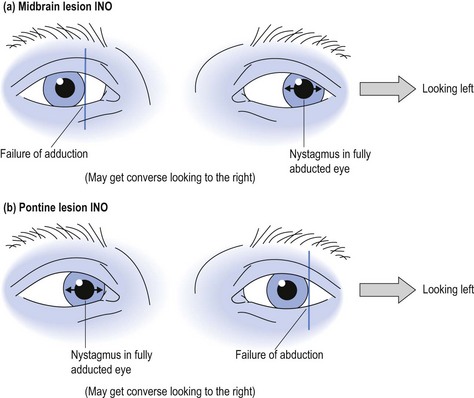

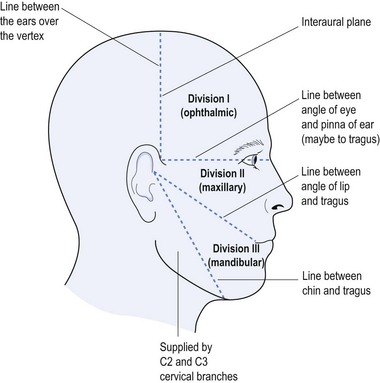

A lesion in the brainstem may cause internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) with involvement of the medial longitudinal bundle that connects the midbrain with the pons, and hence coordinates the movements of the eye muscles. An INO lesion in the midbrain may result in failure to adduct the affected eye due to poor communication between the third cranial nerve and sixth cranial nerve, when looking laterally, with nystagmus in the abducted eye (see Fig 10.4). The converse may be the case with a lesion in the pons (see Fig 10.4).

Fatigue is often a major concern for people with MS. A recent pilot study showed the potential for sleep disorders, such as periodic leg or limb movement in sleep with arousal (PLMS with PLMA) and possibly even obstructive sleep apnoea to be contributing factors to this symptom.7 It follows that referral to a sleep physician and polysomnography may provide additional insight into the associated fatigue with the potential for intervention, such as continuous positive air pressure (CPAP).

Emotional factors may play a significant role within the evolution of MS, both for the affected patient and their relatives and loved ones. Anxiety and depression are often associated with MS. The general practitioner is ideally placed to identify the needs, provide counselling and, when necessary, medication to alleviate these symptoms.

Treatment of MS

Long-term disease modification

Disease modification is very much the domain of the specialist, and the earlier such treatment is initiated the better is the prognosis.8,9 The most widely used disease modifying agents include: Avonex® (interferon beta 1A) administered intramuscularly weekly; Rebif® (interferon beta 1A) injected subcutaneously on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; Betaferon® (interferon beta 1B) injected subcutaneously second daily (on a two-weekly cycle of Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday); or Copaxone® (glatiramer acetate) given subcutaneously every day. Despite the various claims from the different companies, the pivotal trials have confirmed relative equality between all four of these modifying agents with respect to reduction in relapses. Hence the choice of which agent to use remains the province of agreement between the specialist and the patient involved.

Another treatment of the immune system includes mitoxantrone, which is reserved for the difficult cases and can be given to a maximum of 140 mg/m2 of body surface area with the potential for significant adverse effects, such as heart disease. Other immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate or azathioprine, have been used to treat MS as has plasmapheresis, but these definitely remain within the ambit of the specialist.

Symptomatic relief

Amantadine (Symmetrel®) given in the dosage of 100 mg per day has been used to treat MS-related fatigue. As described earlier, sleep disorders, especially PLMS with PLMA, may be a provocateur for fatigue,7 as may obstructive sleep apnoea. A trial of pramipexole (Sifrol®) 250 µg nocte or even L-dopa (Sinemet® 100/25) one nocte may offer symptomatic relief. The possible role of CPAP is also worthy of consideration, but further studies are required.

Counselling

One final consideration must also include addressing the social needs of the disabled patient with MS. General practitioners have a real contribution to make in helping patients find suitable accommodation and, when necessary, appropriate placement for which social worker intervention may be necessary. It is not the role of the consultant only to involve the self-help groups, such as the MS Society, as the general practitioner may be better attuned to the patient’s needs. The MS Society may be ideally placed to assist. Some hospitals, such as Liverpool Hospital in Sydney, have MS nurses who are specifically trained in the care of patients with MS and provide an invaluable resource for the family doctor to ensure access to all available treatment.

1 Freedman MS, Thompson EJ, Deisenhammer F, Giovannoni G, Grimsley G, Keir G, Ohman S, Racke MK, Sharief M, Sindic CJ, Sellebjerg F, Tourtellotte WW. Recommended standard of cerebrospinal fluid analysis in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: A consensus statement. Arch Neurol. 2005 Jun;62(6):865-870.

2 Frohman EM, Goodin DS, Calabresi PA, Corboy JR, Coyle PK, Filippi M, Frank JA, Galetta SL, Grossman RI, Hawker K, Kachuck NJ, Levin MC, Phillips JT, Racke MK, Rivera VM, Stuart WH. The utility of MRI in suspected MS. Neurology. 2003;61:602-611.

3 Kurtzke J. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale. Neurology. 1983;33:1444.

4 Tribe KL, Longley WA, Fulcher G, Faine RJ, Blagus L, Pearce G, Hope AD, Henderson EM. Living with multiple sclerosis in New South Wales, Australia, at the beginning of the 21st century: impact of mobility disability. International J of MS Care. 2006:1-12.

5 Wingerchuk D. Diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica. Neurologist. 2007;13:2-11.

6 Takahashi T, Fujihara K, Nakashima I, et al. Anti-aquaporin-4 antibody is involved in the pathogenesis of NMO: a study on antibody titre. Brain. 2007;130(5):1235-1243.

7 Beran RG, Ainley LA, Holland G. Sleepiness in multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Sleep & Biological Rhythms. 2008;6:194-200.

8 Kappos L, Traboulsee A, Constantinescu C, et al. Long-term subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy in patients with relapsing–remitting MS. Neurology. 2006;67:944-953.

9 Freedman MS, Forrestal FG, on behalf of the PRISMS study group. Canadian treatment optimization recommendations (TOR) as a predictor of disease breakthrough in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with interferon β-1a: analysis of the PRISMS study. Multiple Sclerosis. 2008;14:1234-1241.

Lassmann H, Bruck W, Lucchinetti C. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview. Brain Pathology. 2007;17:210-218.

Miller D, Barkhof F, Montalban X, Thompson A, Filippi M. Clinically isolated syndromes suggestive of multiple sclerosis, part I: natural history, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Lancet Neurology. 2005;4:281-288.

Rovira A, Leon A. MR in the diagnosis and monitoring of multiple sclerosis: an overview. European J of Radiology. 2008;67:409-414.