Chapter 50 Multilevel surgery (hyoid suspension, radiofrequent ablation of the tongue base, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty) with/without genioglossal advancement

1 INTRODUCTION

Severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is preferably treated by nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP). Unfortunately, 30–50% of patients refuse or cannot accept NCPAP for a variety of reasons. Approximately 25% of patients refuse upfront or cannot pass the test period, others cannot accept or refuse it in the long run, or use it for only a few hours per night and/or less than 5 nights per week. It is our experience that increasingly many – especially young – patients refuse NCPAP therapy upfront and ask how realistic surgical alternatives are. Whatever the reason for not using NCPAP, treatment remains indicated in patients with severe OSAS and NCPAP refusal/failure. Many invasive alternatives are being explored. Various surgical interventions are available, such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), Z-PP, uvula flap and other variations, in case of palatal obstruction, and hyoid suspension (HS) and genioglossal advancement (GA), in retrolingual obstruction. Maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) and tracheostomy are usually very effective, but the morbidity of these two modalities limits their application in the first line of surgery. In addition to surgical modalities, minimally invasive interventions exist, such as radiofrequent thermotherapy of palate and/or tongue base (RFTB). Surgery can be divided into unilevel (at palatinal or tongue base level only) and multilevel (surgery at both these levels), and can be performed either staged, or in one surgical event. Nose and nasopharynx in this regard are less important, in that where no nasal blockage is present, it has been shown that there is little use in increasing nasal airflow.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

In severe OSAS, the likelihood that obstruction is present on both a palatinal as well as a retrolingual level is high; in fact, obstruction at both levels is usually responsible for the high Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI). This is confirmed by sleep endoscopy of large series of patients with OSAS, who showed retropalatinal and retrolingual obstruction in a large percentage of cases. For this reason, the effect of unilevel surgery is often disappointing in severe OSAS. A therapeutic dilemma is whether these patients should undergo intervention (and what form of surgery), at both levels staged (and in which sequence) or simultaneously. Performing multilevel surgery in a staged sequence will in the case of multilevel obstruction often lead to a prolonged path to success. Eliminating obstruction at one level while leaving the other obstruction untreated is useless. In this paper we present our experience of one tempo multilevel surgery (hyoid suspension, radiofrequent ablation of the tongue base, UPPP, with/without genioglossal advancement) in severe OSAS and NCPAP failure or refusal, and compare it with the literature. We focus in this chapter on literature concerning UPPP and hyoid suspension with/without radiofrequency of the tongue base; experiences with UPPP and genioglossal advancement without hyoid suspension are covered elsewhere in this book (see Chapter ••)

3 PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients who visited our department from July 2003 to June 2005 because of habitual snoring and/or suspicion of sleep apnea syndrome were evaluated by history, physical examination, full overnight polysomnography and either by midazolam or propofol-induced sedated endoscopy. Patients with moderate to severe OSAS, both retrolingual and retropalatinal narrowing or collapse at sedated endoscopy, and refusal or non-acceptance of NCPAP treatment were offered a multilevel surgical approach. Full night sleep registration was performed preoperatively and 3 months postoperatively (see Chapter 49: Hyoid suspension as only procedure).

Surgical success was defined as AHI < 20 and >50% reduction in AHI and response rate as reduction of AHI between 20 and 50%. The overall response rate was defined as more than 20% reduction in AHI.

3.1 TREATING OBSTRUCTION AT PALATINAL LEVEL

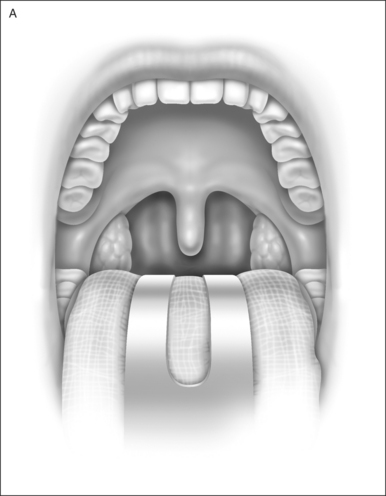

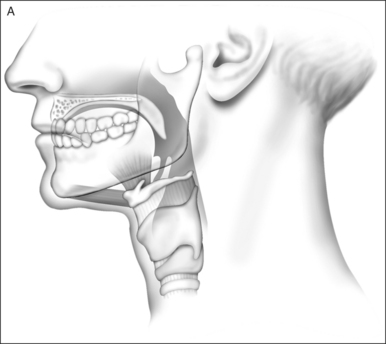

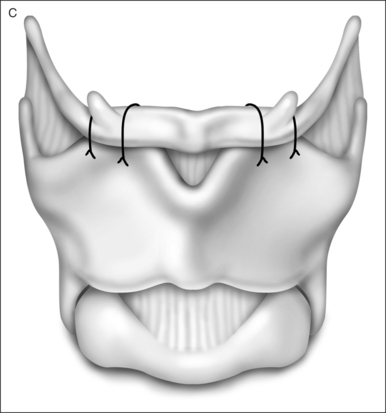

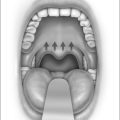

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty was performed according to Fujita’s technique; the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars were trimmed and reoriented, and the uvula was excised to create more retropalatinal space (Fig. 50.1). Tonsillectomy was performed if it had not been donepreviously (in 15 of 22 [68%] patients). In patients whohad had tonsillectomy previously, with a short anterior posterior diameter at retropalatinal level, Z-PP according to Friedman was performed (see Chapter 33).

3.2 TREATING OBSTRUCTION AT TONGUEBASE LEVEL

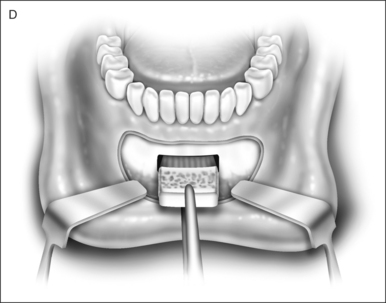

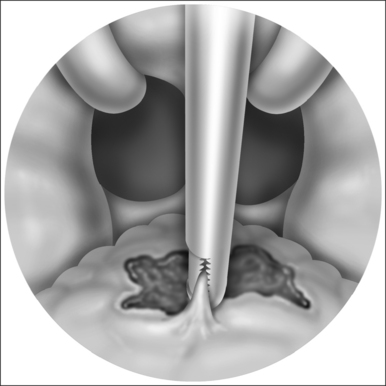

3.2.1 RADIOFREQUENT ABLATION OF THE TONGUE BASE (BIPOLAR, CELON®)

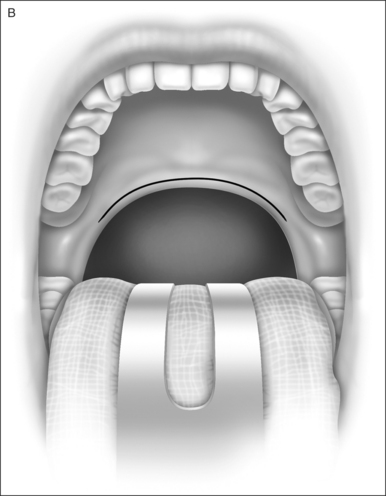

This was used for stiffening of the base of tongue. Energy was delivered with an exclusive needle device through the dorsal surface of the tongue. Evidence-based criteriafor technical adjustment and optimal energy dosageaccording to relevant increase in lesion size were used. After the initial surgical procedure, on indication a second and sometimes third additional RFTB was performed(Fig. 50.2).

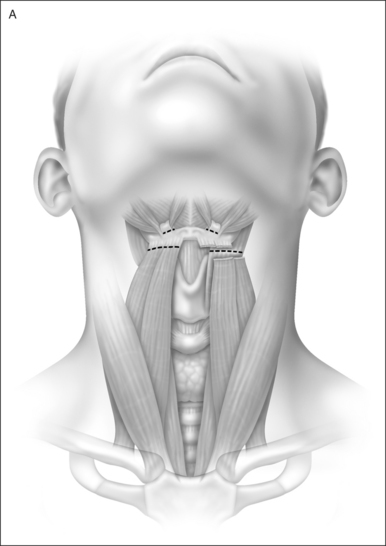

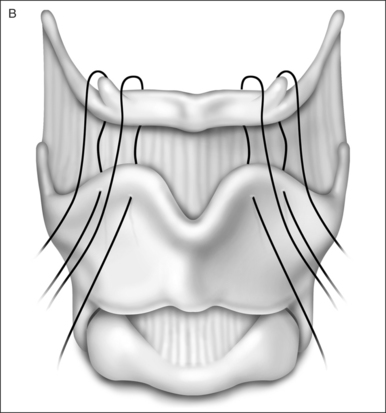

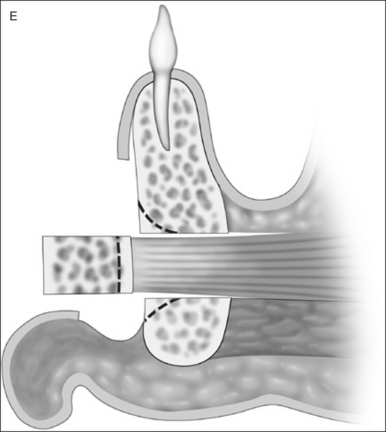

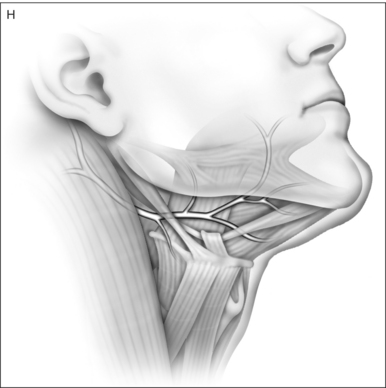

3.2.2 HYOID SUSPENSION

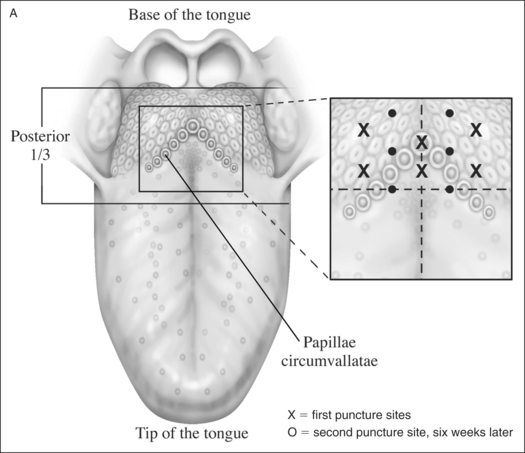

After exposure via an external horizontal incision at the level of the membrana thyrohyoidea, the strap muscles(M. sternohyoideus, M. omohyoideus and M. thyrohyoideus) were divided just below the hyoid and superior to the hyoid the tendon of the stylohyoideus was divided from the hyoid bone (Fig. 50.3) (for details see Chapter 49: Hyoid suspension as only procedure).

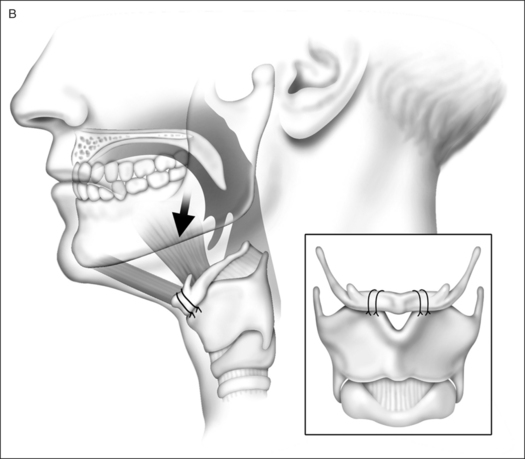

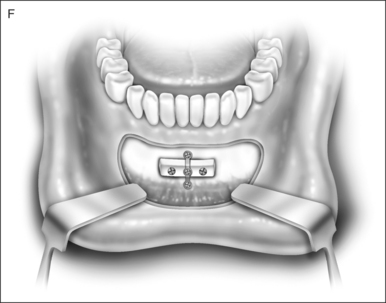

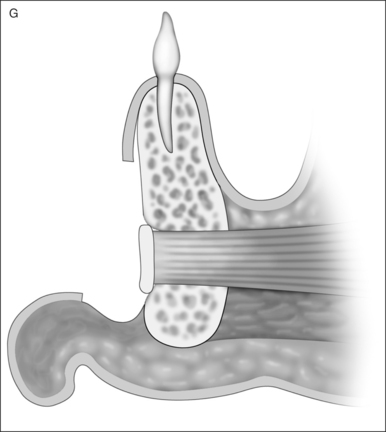

3.2.3 GENIOGLOSSUS ADVANCEMENT

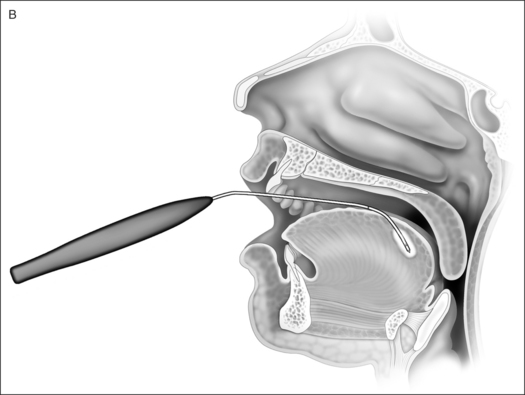

A standard anterior mandibular osteotomy, limited to advancement of a rectangular window of the mandible including the genial tubercle and genioglossus musculature, but without rotation of the segment, was performed. The outer cortex and medulla were removed, the lingual cortical plate advanced and fixed with bone screws (Fig. 50.4).

4 PRE- AND POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Conscientious monitoring of oxygen saturations in an intensive care unit for one night after surgery is mandatory because of the risk of a compromised airway due to postoperative bleeding or edema. All patients received 2 grams of amoxicillin IV during surgery, and 625 mg three times a day orally for one week postoperatively. Oral painkillers were administered. Steroids were not used routinely. Patients were usually discharged 48–72 hours postoperatively.

4.1 STATISTICS

Changes in parameters before and after intervention were compared by means of a Wilcoxon signed rank test (paired analyses). Differences in parameters between interventions (with or without genioglossal advancement) were tested with a Wilcoxon rank sum test. For the binomial proportions (responses) exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

5 RESULTS

Twenty-two patients underwent multilevel surgery, 14 with genioglossal advancement and eight without. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 50.1. Between the groups with and without genioglossal advancement, there were no significant preoperative differences in AHI, AHI supine, Desaturation Index (DI), Body Mass Index (BMI), total sleeping time (TST), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) and Visual analogue score (VAS) scores. Also in treatment outcome there were no significant differences.

Table 50.1 Baseline characteristics

| Measurement | Total subjects(n=22) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.3±7.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7±3.4 |

| AHI | 48.7±19.7 |

| Ratio male : female | 20 : 2 |

BMI: body mass index; AHI: apnea/hypopnea index.

The mean AHI for the total group decreased significantly from 48.7 (range 17.4–100.9) to 28.8 (diff 19.9, SD 18.5, P<0.0001). Surgical success, defined as AHI < 20 and >50% reduction in AHI, was seen in 45% (95% CI24–68%) of patients. Reduction of AHI between 20% and 50%, response rate, was seen in 16 patients (27%). The overall response rate was 72% (95% CI 49–89).

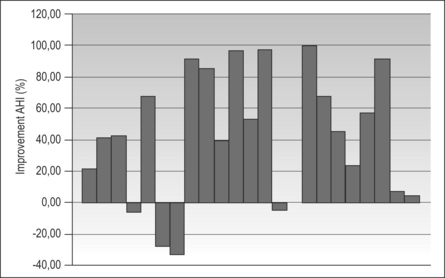

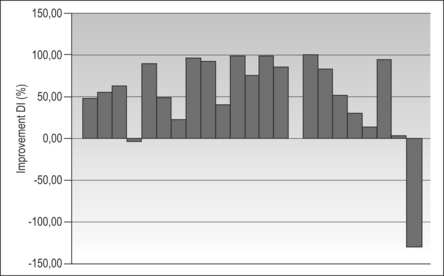

Dividing patients into three groups on the basis of the AHI, the success rates decreased with increasing AHI (Table 50.2). The success rates of patients with an AHI < 55 and >55 were 56% and 0% respectively. Overall, four patients increased in AHI after surgery. The AHI in supine position decreased significantly from 63.3 to 35.6 (P=0.0055). The DI decreased from 31.9 to 17.6 (P<0.0001). In 83.3% of the patients without surgical success the DI did increase. In Figures 50.5 and 50.6 the relative differences in AHI and DI pre- and post-surgery for each patient are shown respectively.

Table 50.2 Success rates on basis of the AHI

| AHI | |

|---|---|

| <40 | 60 |

| 40–55 | 53.8 |

| >55 | 0 |

We did not see differences in preoperative BMI (range 23.8–39) between the successful group and the non-successful group. BMI and TST did not change substantially before and after surgery (respectively P=0.2292 and P=0.3855).

Hypersomnolence during daytime and snoring complaints pre- and postoperatively decreased from 8.6 to 3.6 (P<0.0001) and 8.6 to 3.8 (P<0.0001) respectively. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale improved significantly from 7.4 to 3.9 (P<0.0001).

6 COMPLICATIONS

We did not encounter infection, postoperative hemorrhage, tongue base abscess, compromised airway, or velopharyngeal insufficiency postoperatively. Only one serious complication was seen: a long-lasting hypoglossal nerve paresis. It is unclear whether this was caused by the sutures around the hyoid used for hyoid suspension or by one of the lesions of the radiofrequency in the tongue.

7 DISCUSSION

A variety of interventions, both minimally invasive (RF of palate and tongue base) and surgical (UPPP, Z-PP, uvulaflap, laser glossectomy, hyoid suspension (HS), geniogossal advancement (GA)) have been reported as part of multilevel treatment in severe OSAS and NCPAP failure or non-acceptance, both staged and in one session. We decided to perform multilevel surgery (UPPP, RFTB, HS with/without GA) in one procedure. In a staged surgical procedure, patients are more prone to become discouraged in completing the advised treatment and will be treated only partly.

The application of this surgical approach has resulted in a success rate of 45% and overall response rate of 72%. In eight of the 22 patients we added GA to the UPPP, HS and RFTB. This was not designed as a randomized trial; GA simply became available to us. There were no differences between the groups with and without GA for AHI or BMI. Intriguingly, we found no difference in effect for the groups with and without GA. Since GA can have several complications such as mandible fracture and necrosis, hematomas and infection of the floor of mouth and injury of tooth roots, we presently tend to limit multilevel surgery to UPPP, HS and RFTB, although we are aware that positive results of GA have been reported in the literature (and are discussed elsewhere in this book).

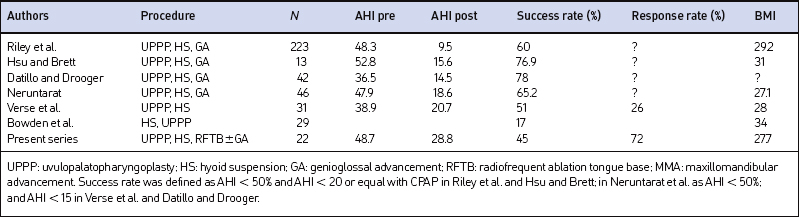

Table 50.3 shows data of reported similar one-stage multilevel surgical interventions (at least UPPP and HS, but not UPPP and GA without HS), with success rates of 42–78% and overall response rates to approximately 73%. Differences in success rates are probably due to variations in study design and patient selection. The severity of OSAS preoperatively differs between the studies. The chance of surgical success is inversely related to the AHI: the higher the AHI preoperatively, the lower the success rate (Table 50.2). Also the definition of success is different between the studies.

For those patients for whom NCPAP therapy is no longer an option an alternative treatment is indicated and even when success (AHI reduction > 50%, below 20) is not reached, response (AHI reduction of 20–50%) can still be of significant value in terms of both increased quality of life and reduction in risk of morbidity and mortality. The sometimes significant discrepancy between subjective impressive improvement and subjective moderate improvement (reduction in AHI) in some patients remains fascinating.

In our series, the AHI of four patients increased after intervention. It is known that 56% of patients with sleep apnea syndrome are position dependent. Two of these four patients were positional and slept more in a supine position postoperatively. One patient had a subtotal nasal septal perforation – too large to attempt to close it – with decreased nasal passage. It is tempting to speculate that this might have played a role in the failure. Another patient had a significant weight gain of almost 10%, which may explain the postoperative higher AHI. Peppard et al. showed that a 10% weight gain predicts an approximate 32% increase in AHI.

When the success rate was elevated according to the severity based on preoperative AHI, there was a clear trend. No patients with an AHI > 55 met the criteria for success. Based on these experiences we have abandoned multilevel surgery (and thus the phased Stanford protocol) in patients with an AHI > 55–60. In these patients MMA is offered upfront, with tracheotomy in reserve as last refuge. The invasiveness of these modalities with significant morbidity indicates that these procedures should be kept for patients with an AHI above 55 as primary surgical treatment, and for non-responders to multilevel surgery with an AHI < 55.

We conclude that one-stage multilevel surgery, in which genioglossal advancement in our hands is not of additional value, can be a valuable addition to the therapeutic armamentarium and can be considered a viable alternative, objective as well as subjective, to NCPAP or as primary treatment in well-selected patients with severe OSAS with an AHI < 55.

1. Bettega G, Pepin JL, Veale D, Deschaux, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Fifty-one consecutive patients treated by maxillofacial surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:641-649.

2. Bowden MT, Kezirian EJ, Utley D, Goode RL. Outcomes of hyoid suspension for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(5):440-445.

3. Datillo DJ, Drooger SA. Outcome assessment of patients undergoing maxillofacial procedures for the treatment of sleep apnea: comparison of subjective and objective results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:164-168.

4. Den Herder C, Kox D, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Bipolar radiofrequency induced thermotherapy of the tongue base: its complications, acceptance and effectiveness under local anesthesia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 263, 2006. (in press)

5. Hsu PP, Brett RH. Multiple level pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. Singapore Med J. 2001;42(4):160-164.

6. Li KK, Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell R, Guilleminault C. Overview of phase I surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78(11):836-837. 841–5

7. Neruntarat C. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy:short-term and long-term results. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(6):482-486.

8. Oksenberg A, Silverberg DS, Arons E, Radwan H. Positional vs, nonpositional obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 1997;112:629-639.

9. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, et al. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA. 2000;284:3015-3021.

10. Richard W, Kox D, den Herder C, et al. The role of sleep position in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otolaryngol. June 27, 2006. Epub ahead of print

11. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111(6):717-721.

12. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(2):117-125.

13. Stuck BA, Köpke J, Maurer JT, Verse T, et al. Lesion formation in radiofrequency surgery of the tongue base. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1572-1576.

14. Verse T, Baisch A, Maurer JT, Stuck BA, Hörmann K. Multi-level surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Short-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:571-577.

15. Vilaseca I, Morillo A, Monserrat JM, et al. Usefulness of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with genioglossus and hyoid advancement in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:435-440.