Chapter 17 Multilevel surgery for obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome

Effective surgical treatment for obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) must be designed to eliminate collapsible soft tissue in the upper airway without interfering with normal function. Creation of a non-collapsible airspace and reduction of airway resistance enables maintenance of adequate airflow with normal inspiratory effort. This translates into elimination or reduction of apneic/hypopneic episodes during sleep, control of symptoms and further minimizes ongoing multi-system damage in OSAHS patients. OSAHS is often caused by multiple levels of obstruction and therefore requires multilevel treatment. In the last decade, several surgical advances have been made in the management of OSAHS.

1 CONCEPT OF MULTILEVEL TREATMENT – ESTABLISHING THE BASIS

1.1 INCIDENCE OF MULTILEVEL OBSTRUCTIONS IN OSAHS PATIENTS

The true incidence of multilevel obstruction is a subject of much debate. Fujita1 first described different anatomic levels of obstruction in OSAHS. He recognized that half of the patients who underwent uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) were non-responders. Most of the non-responders were identified as having multilevel obstruction. Combined oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal obstruction was noted in 54.5% (36/66) of patients in his study. Thus, it is clear that Fujita himself never intended to suggest that UPPP will cure most patients with OSAHS. In 1993, Riley et al.2 reported their surgical experience, outlining a multilevel concept. Each patient was classified as having single level obstruction involving oropharynx only – type 1 – or the hypopharynx only – type 3. Multilevel obstruction was identified as type 2 and implied a combination of oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal obstruction. Of the 239 patients, 93.3% (223 patients) were identified as having multilevel obstruction, type 2. Only 16 patients (6.7%) had single level obstruction. Of these, 10 patients had type 1 obstruction and six patients had type 3 obstruction.

This early classification by Fujita and Riley was based on physical examination of the patients with vague guidelines. Specific criteria for identifying unilevel versus multilevel obstruction were not reported. Subsequent development of the Friedman tongue position (FTP) allowed for a simplified method of staging the levels of obstruction.3,4 The early data based on FTP indicated that approximately 25% of patients presenting with OSAHS had unilevel obstruction, while 75% had multilevel obstruction.

To more precisely identify the anatomic sites of obstruction during sleep, sleep endoscopy was proposed as a preferred method. den Herder et al.5 reported an unusually high number of single level obstructions. In their study of 127 patients, 63% had single level obstruction while only 37% had multilevel disease. The study, however, may have misidentified the level of obstruction; tongue base obstruction pushing the palate backward causing secondary palatal obstruction may have been classified as primary palatal obstruction.6 Another study by Abdullah van Hasselt confirmed the high incidence of multilevel disease and 87% of their 893 patient populations had multilevel obstruction.7

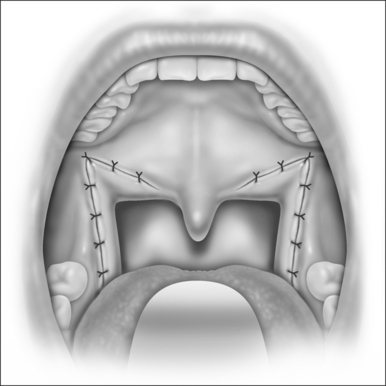

1.2 SINGLE LEVEL SURGERY CANNOT BE THE ONLY TREATMENT FOR MOST OSAHS PATIENTS

UPPP was designed to enlarge the oropharyngeal airway8 and remains the most common surgical intervention for OSAHS. Review of the literature indicates the success rate (a 50% reduction in Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) and a postoperative AHI of less than 20) for UPPP as an isolated procedure ranges from 25% to 80%. However, Sher et al.9 reported success rates for UPPP around 41% based on a meta-analysis of unselected cases. Although there are many reasons UPPP may fail, uncorrected retrolingual obstruction has been clearly identified as a major cause. This seems to support the concept that multiple levels of obstruction exist and explains why UPPP alone frequently results in failure.

1.3 MULTILEVEL SURGERY IS NOT LIMITED TO SEVERE DISEASE

Many otolaryngologists presume that although UPPP may not cure the patients with severe OSAHS, it is likely to be effective for patients with mild disease. There are however many studies indicating that the severity of disease is not a predictor of success with single level surgery.3,4,10 Senior et al.11 studied a group of patients with mild OSAHS (AHI less than 15). These patients underwent UPPP and the success rate was only 40%. Friedman further studied a series of patients with mild disease and showed an overall success rate of approximately 40% as well.3,4 If indeed most patients have multilevel disease, the success for the surgical treatment of mild OSAHS is not better than those for treating severe disease. In fact, the basis of the Friedman staging system is that anatomic findings are the most significant factors, rather than severity of disease. Multilevel surgery should not be reserved exclusively for the treatment of severe disease. It is therefore reasonable that multilevel treatment should be considered for most patients with mild disease as well as most patients with severe disease. Since the majority of patients suffering from OSAHS do have multilevel disease and directing the therapy to a single anatomic level has a high potential for failure, the need for multilevel therapy is evident.

2 HISTORY OF MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

Published data on multilevel treatment can be divided into four groups.

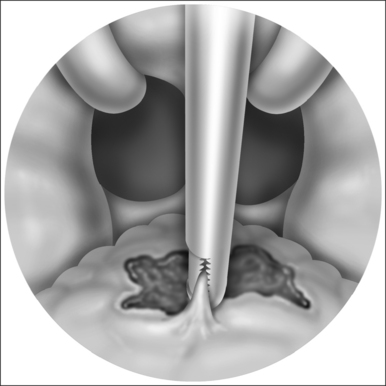

3 MULTILEVEL MINIMALLY INVASIVE TREATMENT FOR MILD/MODERATE OSAHS

Many options are available for minimally invasive treatment of palatal obstruction. Minimally invasive treatment options for retrolingual obstruction are limited, but have been in clinical use. There have been a few studies that looked at multilevel minimally invasive treatment. Steward19 studied 22 patients who underwent combined radiofrequency reduction of the palate and the base of tongue and reported a success rate of 59%. None of the patients had concomitant nasal surgery. Fischer et al. presented a similar study about multilevel minimally invasive surgery with radiofrequency on the palate, tonsil and tongue base for 15 OSAHS patients.20 The results showed that the AHI changed from 32.6±17.4 preoperatively to 22±15 for a success rate of 33%. Whereas the majority of Fischer’s patients had moderate disease, Steward’s patients had mild-to-moderate disease.

In 2004, Stuck et al.21 published their surgical results with radiofrequency on the palate and base of the tongue for 18 OSAHS patients with mild/moderate disease. They reported their success rate as 33.3% (by their definition of success, a postoperative AHI reduction of at least 50% and below a value of 15).

In 2007, we presented our experience on minimally invasive single-stage multilevel surgery (MISSMLS) for patients with mild/moderate OSAHS.22 Our patients underwent three-level treatment that included nasal surgery, palatal stiffening by pillar implant technique and radiofrequency volume reduction of the tongue base with a minimum follow-up of 6 months. The results in a retrospective review of a prospective dataset showed that both subjective and objective outcomes improved significantly, and treatment morbidity was minimal and only temporary. Mean bedpartner’s snoring visual analog scale (VAS) decreased from 9.4±0.9 preoperatively to 3.2±2.4 postoperatively. Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) decreased from 9.7±3.9 preoperatively to 6.9±3.3 postoperatively. Mean AHI was reduced from 23.2±7.6 to 14.5±10.2. Classic success was achieved in 54 of 122 patients (47.5%).

4 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON MULTILEVEL TREATMENT FOR OSAHS PATIENTS

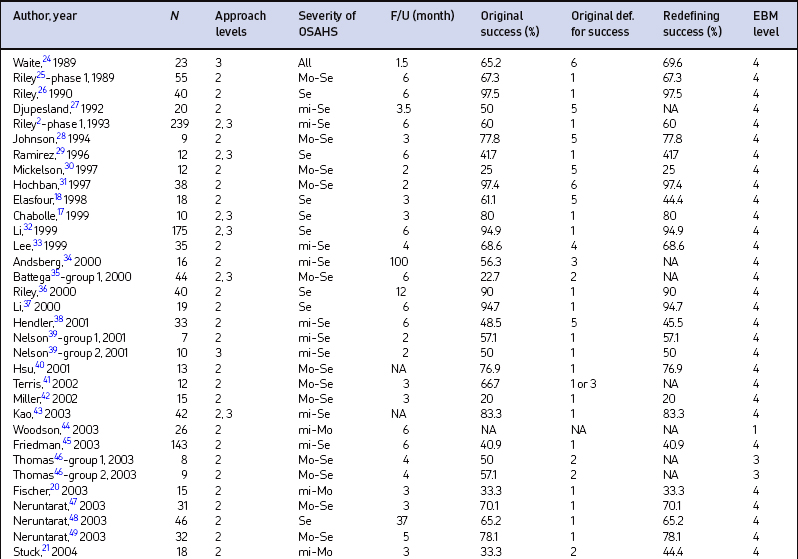

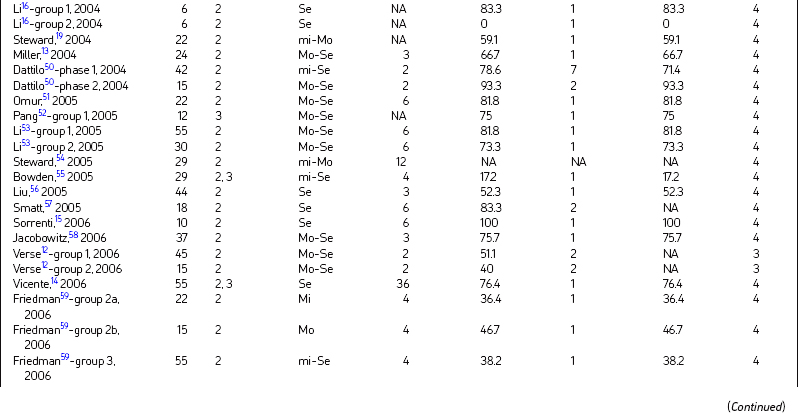

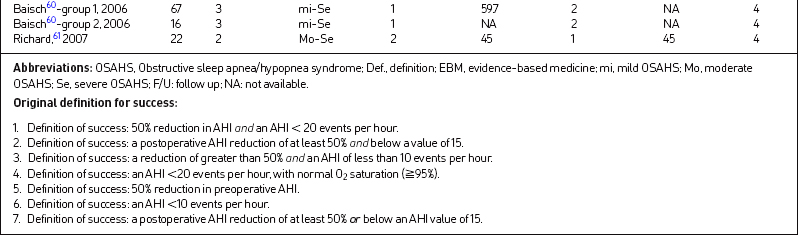

We recently reported on a systematic review of all English language literature on multilevel surgery for OSAHS patients as of 31 March 2007.23 Article titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine article eligibility. We also identified relevant publications from the lists of references in this subset of articles. The study design and its corresponding level of evidence were clarified as follows: (1) Level 1 – randomized controlled trials or a systematic review; (2) Level 2 – prospective cohort study; (3) Level 3 – case–control study; (4) Level 4 – case series; and (5) Level 5 – expert opinion.

There were 49 papers (58 groups) selected for final inclusion after detailed review (Table 17.1). There were 1978 subjects included in the study with a pooled mean age of 46.2 years. The mean minimal time period from multilevel surgery to postoperative PSG was 7.3 months (range, 1–100 months).

Multilevel surgery for OSAHS is obviously associated with improved outcomes, although this benefit is supported largely by level 4 evidence. Future research should conduct larger, higher level and longer-term studies to further validate the results.

4.1 SHORT-TERM VERSUS LONG-TERM RESULTS OF MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

Most of the literature on multilevel treatment of OSAHS reported short-term surgical results at 6 months or less after surgery. The success rate varied from 0% to 100%. Vicente14 studied the long-term efficacy of UPPP and tongue base suspension with the Repose system for severe OSASHS and reported a 78% success rate at 3 years after surgery. Neruntarat48 performed uvulopalatal flap in conjunction with GAHM in 46 patients and followed the short-term (6 months after surgery) and long-term (at least 37 months postoperatively) outcome. The short-term and long-term success rates were 78.3% and 65.2%, respectively. Six (16.7%) patients with short-term success failed over the long term and these patients had significant increase in BMI.

The longest follow-up result in multilevel treatment was reported by Andsberg et al.34 using a 50% reduction in the Apnea Index as the definition for success. They reported on 16 patients at 1 year and 8.4 years after surgery. Their success rates were 56% and 56%, respectively. The weights of the patients remained stable during the follow-up period. Although there is a perception that the long-term results are poorer than the short-term results for surgical treatment of OSAHS, the studies showed the reduction in surgical success was only moderate and that the majority of patients at 6 months maintain long-term successful outcomes.

4.2 SINGLE STAGE OR MULTI-STAGED SURGERY IN MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

Olsen62 stated that when nasal obstruction is identified, it is usually addressed with a multi-staged procedure after the palate and hypopharyngeal areas are treated. Hsu40 also stated that the timing of nasal surgery in patients undergoing other procedures for OSAHS remains controversial. He feels that performing multi-staged procedures is a safer option in the surgical management of patients with moderate to severe OSAHS. The presence of blood, secretion or edema may add to the severity of obstruction in an already narrow and obstructed upper airway in patients with moderate to severe OSAHS. The addition of nasal packing may further compromise the airway.

However, most studies revealed that single stage surgery at multiple levels did not increase postoperative complications.52,53,63 Single stage multilevel surgery can lower total hospitalization expenses when compared to multi-staged surgery.53 Kieff and Busaba64 studied the safety of same-day or overnight discharge and concluded that same-day discharge for patients who have undergone combined nasal and palatal surgery for OSAHS is relatively safe in selected cases when significant comorbid diseases are not present.

Most of the above literature preferred single stage surgery primarily focusing on nasal and palatal surgery; however, there was no additional hypopharyngeal procedure included. Experience with multilevel surgery with a hypopharyngeal procedure has shown the postoperative morbidity (the highest complication rate) of single stage and multi-staged surgeries to be 40.9% and 39.1%, respectively.19,48 All of the complications were temporary.

Thus, on the issue of single or multiple stage surgery, our opinion is that it is safe and efficacious to perform multilevel surgery in one surgical session using minimally invasive techniques and with adequate postoperative monitoring for patients with mild/moderate OSAHS. When multilevel invasive procedures are necessary, the authors prefer to limit the number of levels to one or two per stage. Three-level invasive surgery is never performed in a single stage.

4.3 ROLE OF NASAL SURGERY IN MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

Multilevel treatment generally includes the palate and tonsil, as well as the hypopharynx. Often, a nasal corrective procedure is included as well. The importance of nasal breathing during sleep has been documented.65 Nasal obstruction also plays a role in the pathogenesis of OSAHS.66 According to the Bernouilli principle (Venturi effect), intraluminal pressure in the compromised airspace suddenly drops if the inspired airway accelerates to keep ventilatory volume constant. The effect further narrows the airspace (hypnogenic stenosis). When inspiratory negative pressure reaches a certain critical point in the effort to overcome increased upper airway resistance, a combination of redundant soft tissues and loss of pharyngeal muscle tone and decreased tongue muscle tone causes complete upper airway collapse on inspiration.

It is well known that nasal cross-sectional area reduced by septal deviation or other pathology causes increased nasal resistance and predisposes the OSAHS patients to downstream inspiratory collapse of the oropharynx, hypopharynx or both.67,68 Correction of the nasal airway, however, does not always improve OSAHS. In fact it may result in an unexpectedly worse AHI postoperatively. Friedman69 conducted a prospective study of 50 consecutive patients with nasal airway obstruction and OSAHS to compare the effect of an improved nasal airway on OSAHS by use of subjective and objective measures. The results demonstrated that although 98% of patients had subjective improvement in nasal breathing, 66% of patients did not notice any significant change in their snoring. Review of the polysomnographic data demonstrated that the group overall did not have significant changes in AHI or LSAT. The subgroup of patients with mild OSAHS showed the most significant worsening in their AHI. CPAP levels, however, required to correct OSAHS decreased significantly after nasal surgery. Verse et al.70 also reported a similar study with 26 adult patients who underwent nasal surgery as single level treatment of their sleep-related breathing disorders. They concluded that nasal surgery alone had a limited efficacy in the treatment of adult patients with OSAHS. Nevertheless, nasal surgery significantly improves sleep quality and daytime sleepiness independent of the severity of OSAHS.

5 SUGGESTED TECHNIQUES FOR MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

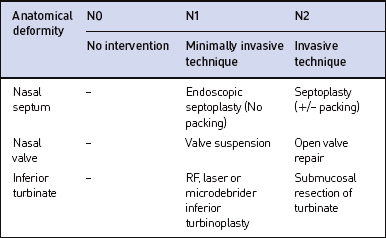

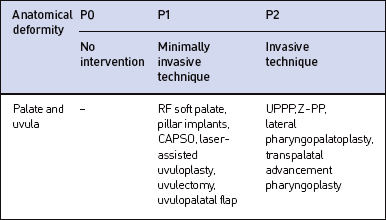

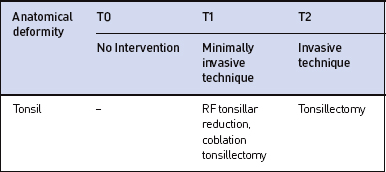

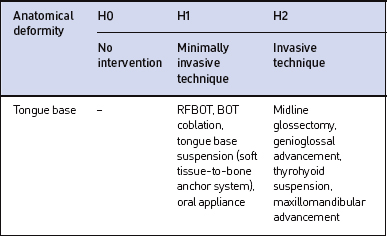

When making a decision to select a treatment plan for the OSAHS patient, the balance between morbidity of treatment and severity of disease needs to be considered. We present an algorithm (Tables 17.2 to 17.5) used in our practice to plan treatment on the nose, palate, tonsil and hypopharynx. The entire surgical plan should be outlined prior to onset of treatment rather than embarking on a series of trial and error procedures. It is also important to emphasize that the severity of disease and ease or difficulty of correction in OSAHS do not always correlate with the severity of anatomical obstruction.10 Thus, an algorithm for successful surgical treatment of OSAHS should be based on the combination of the anatomic abnormality and severity of disease (the symptoms of snoring alone vs. snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness, and PSG data). The anatomic sites, nose, palate, tonsil and hypopharynx, are identified by N, P, T and H. The level of treatment is described by a number between 0 and 2 (0: no abnormality and therefore no intervention; 1: mild abnormality requiring minimally invasive intervention; 2: severe abnormality/disease requiring invasive correction). Each patient is identified as NxPxTxHx for treatment plan, where x represents a number from 0–2.

6 RISK MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS OF MULTILEVEL TREATMENT

The complication rate for multilevel treatment is the sum of the complications for each of the individual procedures. In our systematic review23 of multilevel surgery for OSAHS patients, the overall complication rate is 14.6%. The complication rates developed in mild/moderate disease and severe disease were 16% and 14.2%, respectively.

1. Fujita S. UPPP for sleep apnea and snoring. Ear Nose Throat J. 1984;63:227-235.

2. Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 1993;108:117-125.

3. Friedman M., Tanyeri H., La Rosa M., Landsberg R., Vaidyanathan K., Pieri S., Caldarelli D. Clinical predictors of obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1901-1907.

4. Friedman M., Ibrahim H., Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13-27.

5. den Herder C., van Tinteren H., de Vries. Sleep endoscopy versus modified Mallampati score in sleep apnea and snoring. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:735-739.

6. Friedman M. Letter to the editor. Comment in Sleep endoscopy versus modified Mallampati score in sleep apnea and snoring. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 2072–2073

7. Abdullah V.J., van Hasselt C.A. Video sleep nasendoscopy. In: Terris D.J., Goode R.L., editors. Surgical Management of Sleep Apnea and Snoring. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2005:143-154.

8. Fujita S., Conway W., Zorick F., Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

9. Sher A.E., Schechtman K.B., Piccirillo J.F. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

10. Friedman M., Vidyasagar R., Bliznikas D., Joseph N. Does severity of obstructive of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome predict uvulopalatopharyngoplasty outcome? Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2109-2113.

11. Senior B.A., Rosenthal L., Lumley A., Gerhardstein R., Day R. Efficacy of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in unselected patients with mild obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:179-182.

12. Verse T., Baisch A., Maurer J.T., Stuck B.A., Hormann K. Multilevel surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: short-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:571-577.

13. Miller F.R., Watson D., Boseley M. The role of the genial bone advancement trephine system in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in the multilevel management of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:73-79.

14. Vicente E., Marin J.M., Carrizo S., Naya M.J. Tongue-base suspension in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea: long-term follow-up results. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1223-1227.

15. Sorrenti G., Piccin O., Mondini S., Ceroni A.R. One-phase management of severe obstructive sleep apnea: tongue base reduction with hyoepiglottoplasty plus uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:906-910.

16. Li H.Y., Wang P.C., Hsu C.Y., Chen N.H., Lee L.A., Fang T.J. Same-stage palatopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal surgery for severe obstructive sleep apnea. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:820-826.

17. Chabolle F., Wagner I., Blumen M.B., Sequert C., Fleury B., De Dieuleveult T. Tongue base reduction with hyoepiglottoplasty: a treatment for severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1273-1280.

18. Elasfour A., Miyazaki S., Itasaka Y., Yamakawa K., Ishikawa K., Togawa K. Evaluation of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998;537:52-56.

19. Steward D. Effectiveness of multilevel (tongue and palate) radiofrequency tissue ablation for patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2073-2084.

20. Fischer Y., Khan M., Mann W.J. Multilevel temperature-controlled radiofrequency therapy of soft palate, base of tongue, and tonsils in adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1786-1791.

21. Stuck B.A., Starzak K., Hein G., Verse T., Hormann K., Maurer J.T. Combined radiofrequency surgery of the tongue base and soft palate in obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:827-832.

22. Friedman M., Lin H.C., Gurpinar B., Joseph N.J. Minimally invasive single-stage multilevel treatment for obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1859-1863.

23. Lin H.C., Friedman M., Chang H.W., Gurpinar B. The efficacy of multilevel surgery of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Lanyngoscope. 2008;18:902-908.

24. Waite P.D., Wooten V., Lachner J., Guyette R.F. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery in 23 patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1256-1260.

25. Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial surgery and obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 80 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:353-361.

26. Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Guilleminault C. Maxillary, mandibular, and hyoid advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 40 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:20-26.

27. Djupesland G., Schrader H., Lyberg T., Refsum H., Lilleas F., Godtlibsen O.B. Palatopharyngoglossoplasty in the treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1992;492:50-54.

28. Johnson N.T., Chinn J. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy with genioglossus advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1994;105:278-283.

29. Ramirez S.G., Loube D.I. Inferior sagittal osteotomy with hyoid bone suspension for obese patients with sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:953-957.

30. Mickelson S.A., Rosenthal L. Midline glossectomy and epiglottidectomy for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:614-619.

31. Hochban W., Conradt R., Brandenburg U., Heitmann J., Peter J.H. Surgical maxillofacial treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:619-626.

32. Li K.K., Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Troell R., Guilleminault C. Overview of phase II surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78:854-857. 851

33. Lee N.R., Givens C.D., Wilson J., Robins R.B. Staged surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 35 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:382-385.

34. Andsberg U., Jessen M. Eight years of follow-up – uvulopalatopharyngoplasty combined with midline glossectomy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;543:175-178.

35. Bettega G., Pépin J.L., Veale D., Deschaux C., Raphaël B., Lévy P. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Fifty-one consecutive patients treated by maxillofacial surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:641-649.

36. Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Li K.K., Troell R.J., Guilleminault C. Surgery and obstructive sleep apnea: long-term clinical outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:415-421.

37. Li K.K., Riley R.W., Powell N.B., Guilleminault C. Maxillomandibular advancement for persistent obstructive sleep apnea after phase I surgery in patients without maxillomandibular deficiency. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1684-1688.

38. Hendler B.H., Costello B.J., Silverstein K., Yen D., Goldberg A. A protocol for uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, mortised genioplasty, and maxillomandibular advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an analysis of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:892-897.

39. Nelson L.M. Combined temperature-controlled radiofrequency tongue reduction and UPPP in apnea surgery. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80:640-644.

40. Hsu P.P., Brett R.H. Multiple level pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:160-164.

41. Terris D.J., Kunda L.D., Gonella M.C. Minimally invasive tongue base surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:716-721.

42. Miller F.R., Watson D., Malis D. Role of the tongue base suspension suture with The Repose System bone screw in the multilevel surgical management of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:392-398.

43. Kao Y.H., Shnayder Y., Lee K.C. The efficacy of anatomically based multilevel surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:327-335.

44. Woodson B.T., Steward D.L., Weaver E.M., Javaheri S. A randomized trial of temperature-controlled radiofrequency, continuous positive airway pressure, and placebo for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:848-861.

45. Friedman M., Ibrahim H., Lee G., Joseph N.J. Combined uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and radiofrequency tongue base reduction for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:611-621.

46. Thomas A.J., Chavoya M., Terris D.J. Preliminary findings from a prospective, randomized trial of two tongue-base surgeries for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:539-546.

47. Neruntarat C. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy under local anesthesia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:85-91.

48. Neruntarat C. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy: short-term and long-term results. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117:482-486.

49. Neruntarat C. Hyoid myotomy with suspension under local anesthesia for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:286-290.

50. Dattilo D.J., Drooger S.A. Outcome assessment of patients undergoing maxillofacial procedures for the treatment of sleep apnea: comparison of subjective and objective results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:164-168.

51. Omur M., Ozturan D., Elez F., Unver C., Derman S. Tongue base suspension combined with UPPP in severe OSA patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:218-223.

52. Pang K.P. One-stage nasal and multi-level pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea: safety and efficacy. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119:272-276.

53. Li H.Y., Wang P.C., Hsu C.Y., Lee S.W., Chen N.H., Liu S.A. Combined nasal-palatopharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: simultaneous or staged? Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:298-303.

54. Steward D.L., Weaver E.M., Woodson B.T. Multilevel temperature-controlled radiofrequency for obstructive sleep apnea: extended follow-up. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:630-635.

55. Bowden M.T., Kezirian E.J., Utley D., Goode R.L. Outcomes of hyoid suspension for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:440-445.

56. Liu S.A., Li H.Y., Tsai W.C., Chang K.M. Associated factors to predict outcomes of uvulopharyngopalatoplasty plus genioglossal advancement for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2005;15:2046-2050.

57. Smatt Y., Ferri J. Retrospective study of 18 patients treated by maxillomandibular advancement with adjunctive procedures for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:770-777.

58. Jacobowitz O. Palatal and tongue base surgery for surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:258-264.

59. Friedman M., Vidyasagar R., Bliznikas D., Joseph N.J. Patient selection and efficacy of pillar implant technique for treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:187-196.

60. Baisch A., Maurer J.T., Hörmann K. The effect of hyoid suspension in a multilevel surgery concept for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:856-861.

61. Richard W., Kox D., den Herder C., van Tinteren H., de Vries N. One stage multilevel surgery (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, hyoid suspension, radiofrequent ablation of the tongue base with/without genioglossus advancement), in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:439-444.

62. Olsen K.D. The role of nasal surgery in treatment of OSA. Op Tech in Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2:63-68.

63. Busaba N.Y. Same-stage nasal and palatopharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: is it safe? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:399-403.

64. Kieff D.A., Busaba N.Y. Same-day discharge for selected patients undergoing combined nasal and palatal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:128-131.

65. Lavie P. Rediscovering the importance of nasal breathing in sleep or, shut your mouth and save your sleep. J Laryngol Otol. 1987;101:558-563.

66. Busaba N.Y. The nose in snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;7:11-13.

67. Olsen K.D., Kern E.B., Westbrook P.R. Sleep and breathing disturbance secondary to nasal obstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:804-810.

68. Cole P., Haight J.S. Mechanisms of nasal obstruction in sleep. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1557-1579.

69. Friedman M., Tanyeri H., Lim J.W., Landsberg R., Vaidyanathan K., Caldarelli D. Effect of improved nasal breathing on obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:71-74.

70. Verse T., Maurer J.T., Pirsig W. Effect of nasal surgery on sleep-related breathing disorders. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:64-68.