Chapter 44 Multilevel pharyngeal surgeryfor obstructive sleep apnea

1 INTRODUCTION

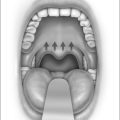

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the commonest sleep disorder. It is characterized by repetitive apneas and hypopneas during sleep. These events are due to partial or complete collapse of the upper airway, resulting in decreased oxygenation and sympathetic overdrive. Frequent arousals occur, causing sleep fragmentation leading to excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, poor concentration, memory loss, frustration, depression and even marital discord. The mechanism of upper airway collapse in OSA is usually multifactorial. Many authors concur that most patients with moderate and severe OSA are very likely to have multilevel obstruction involving the level of the palate and the base of tongue. Endoscopic examination with Mueller’s maneuver can grade airway collapse at three levels, namely the velopharynx, lateral pharyngeal wall and the base of tongue.1 There are surgical procedures that can address the various levels of collapse in these patients. Recently, lateral pharyngeal wall collapse has also been dealt with by creating tension in the lateral walls by lateral pharyngoplasty2 or expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty.3 Palatal collapse can be treated by traditional uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, Z-plasty or transpalatal advancement; tongue base can be reduced by a glossectomy or a suspension sling suture.

Although a staged approach to the upper airway reconstruction is acceptable, and even endorsed by the American Sleep Disorders Association,4 when the likelihood of multilevel obstruction is high, the chances of surgical success may be nearly doubled by addressing multiple anatomic sites at a single surgical sitting,5,6 thereby avoiding additional general anesthetic. The initial staged approach was described by Fujita, when he introduced uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for OSA7; he recognized that the upper airway may collapse at multiple levels. Hence, he described the laser midline glossectomy for patients who failed UPPP and who were diagnosed to have retrolingual obstruction.8 It was Riley et al.6 who first advocated simultaneous multilevel pharyngeal surgery for patients with multilevel obstruction noted clinically on Mueller’s maneuver. They showed promising success with minimal complications. Many authors have reported minimal complications with one-stage multilevel pharyngeal surgery for patients with OSA.9–11

2 PATIENT SELECTION

Surgical techniques for the treatment of OSA have long been criticized and frowned upon, especially uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty (UPPP). Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty remains the most common surgical procedure performed for sleep disordered breathing (SDB). Traditionally, UPPP was used mainly for patients with collapse/obstruction of the soft palate during Mueller’s maneuver (MM). Mueller’s maneuver was first described by Borowiecki and Sassin for the preoperative assessment of OSA.12 According to Fujita’s three types of collapse of the upper airway during sleep,13 Mueller’s maneuver was able to identify Fujita type I (soft palatal) collapse, and hence, isolate patients suitable for UPPP. This, unfortunately, was not always the case,as there are multiple factors involved in the dynamics of OSA, and many patients have multilevel obstructions.Due to the varied clinical indications for this procedure, many authors have found unfavorable postoperative results. Sher et al. reviewed a meta-analysis of reported UPPPprocedures and found an overall success rate of only 40%.14 In an attempt to improve surgical success rates, Friedmanet al. devised a clinical staging system for SDB in orderto better select patients for the UPPP.15 They describedthree stages based on Friedman tongue position, tonsil size and BMI.

Friedman reported an overall success rate of 80.6% for stage I, 37.9% for stage II and 8.1% for stage III. It is well accepted that patients with Friedman tongue position 3 and 4 are indicative of a large tongue, suggesting that if surgery is contemplated, some form of tongue base surgery would be appropriate as well. Most authors concur that patients who are noted to have multilevel collapse with Mueller’s maneuver on endoscopy (of both the palate and tongue base) should have both levels addressed at the samesurgical sitting. Friedman et al. showed that selected patients with stage II and stage III disease treated with UPPP and tongue base reduction using a radiofrequency technique (TBRF) had remarkably improved results.16 Follow-up at 6 months showed successful treatment of patients with stage II disease with success rate improving from 37.9% to 74.0%, and stage III disease improving from 8.1% to 43.3%.16

Severity of OSA has also been noted to correlate with clinical examination, namely Mueller’s maneuver.17 It was demonstrated in 102 patients that OSA severity strongly correlated with Mallampati grade (r=0.389, P<0.0001), Friedman clinical staging (r=0.331, P=0.0007) and Mueller’s grades of collapsibility, at all three levels. Of significance, only 6.9% of patients with mild OSA had a >50% collapse of the base of tongue region, as compared to 65.9% of patients with severe OSA.17 This illustrates that patients with severe OSA are 10 times more likely to have tongue base collapse than patients with mild OSA. Hence, patients with severe OSA and with tongue base collapse noted on Mueller’s maneuver, falling into Friedman stage II or III, should have multilevel surgery in order to achieve the best possible results. In the uncommon event that a single, severely obstructed site in the upper airway is identified, a staged approach may be considered even if the OSA is severe.

Nasal surgery is offered when the patient has significant nasal obstruction that has failed medical therapy (topical nasal steroids), especially when the patient would want correction of the nasal obstruction independent of its effecton their sleep. However, it is reported that nasal surgery alone has only a 15.8% success rate as a treatment of OSA.18 The debate would be the safety of multilevelsurgery, addressing all three levels: the nose, palate and tongue base at the same surgical sitting. Most authors concur that there is no evidence of increased complication rate or morbidity with these procedures performed together.11,19–21

3 OUTLINE OF PROCEDURES

3.1 HYOID MYOTOMY (SUSPENSION)

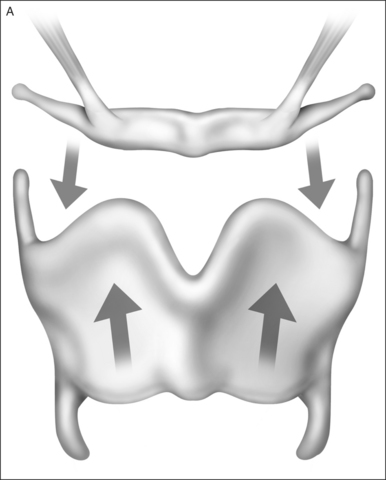

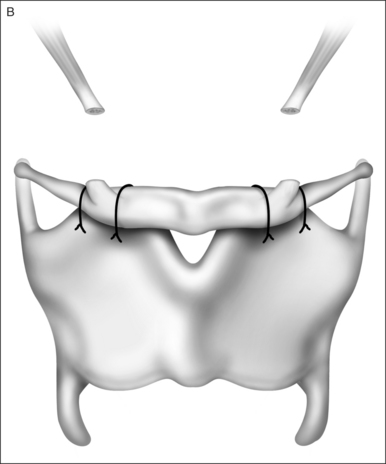

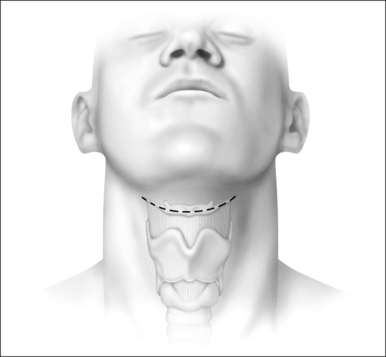

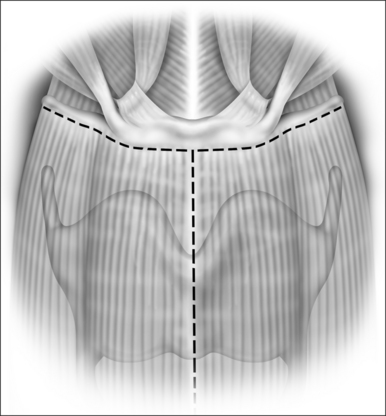

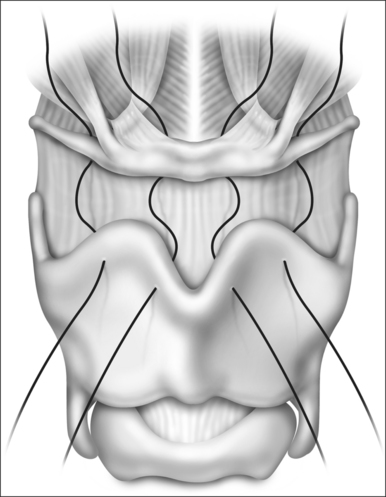

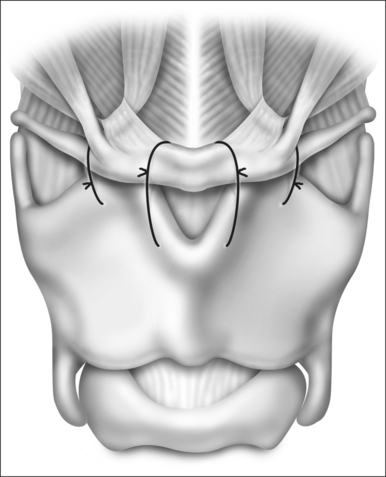

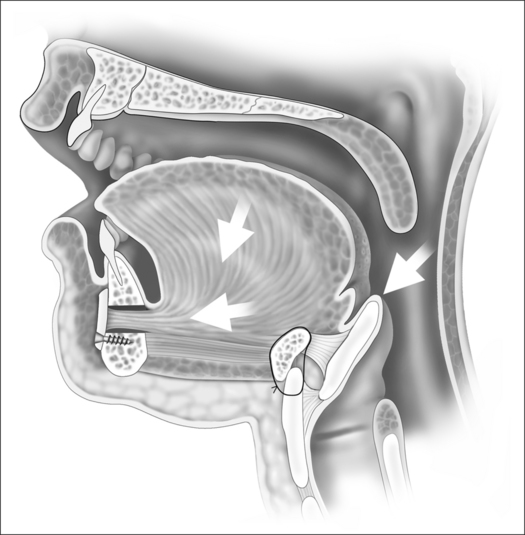

Riley et al.22 first reported a skeletal approach to hypopharyngeal obstruction by using an adaptation of the laryngeal suspension procedure originally developed to minimize aspiration in patients who had had a supraglottic laryngectomy. In their original description, the infrahyoid musculature was removed from the hyoid bone, which was then suspended from the anterior mandibular arch using fascia lata. The technique was later simplified23 by approximating the hyoid bone antero-inferiorly to the thyroid cartilage (Figs 44.1 to 44.5). Essentially, the hyoid is releasedfrom its inferior attachments and advanced anteriorly and inferiorly over the thyroid cartilage. This applies tensionto the hyoepiglottic ligament, enlarging the hypopharynx (see figures).

3.2 MANDIBULAR OSTEOTOMY WITH TONGUE ADVANCEMENT

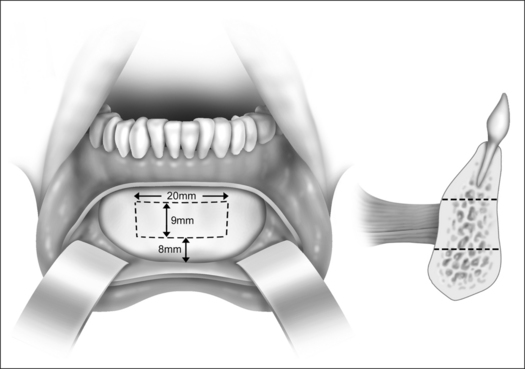

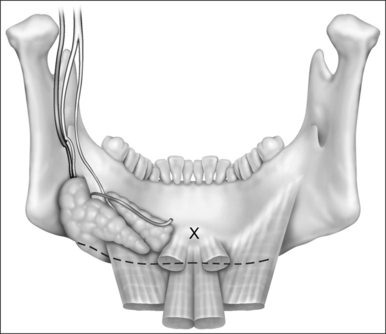

A limited rectangular mandibular osteotomy has replaced the originally described sliding inferior sagittal osteotomy22 as the preferred approach to advancing the genioglossus muscle anteriorly, thereby enlarging the retrolingual space. Powell et al.24 first described this technique that made the surgery safer and more practical for the general otolaryngologist to perform. This procedure can be done in combination with the hyoid myotomy.

3.2.1 TECHNICAL HIGHLIGHTS

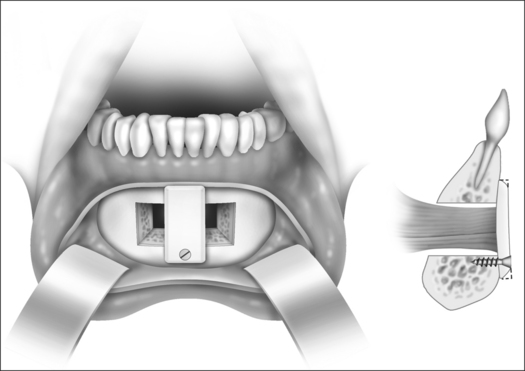

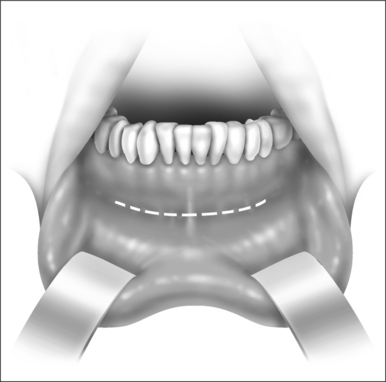

Fig. 44.6 (GGA 1). Inferior gingivolabial incision made for exposure of the anterior table of the mandible.

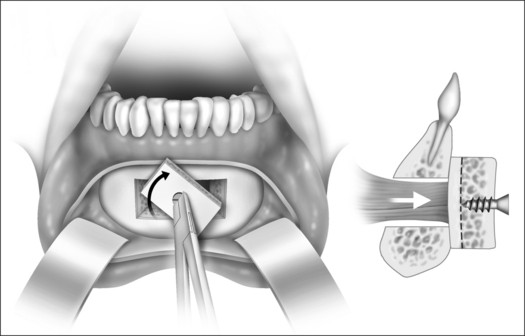

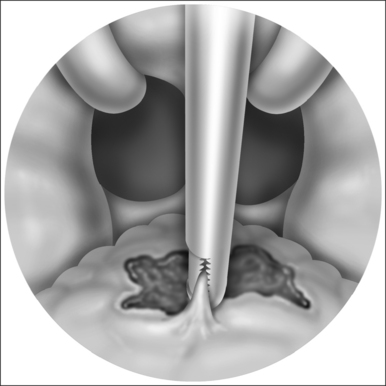

3.3 TONGUE SUSPENSION

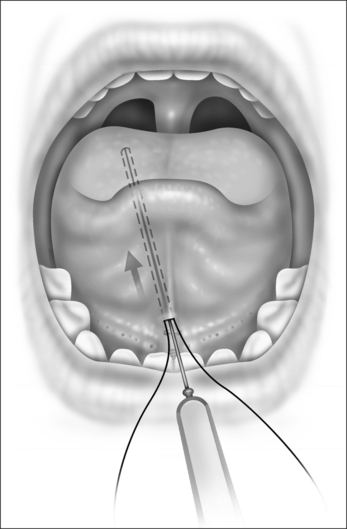

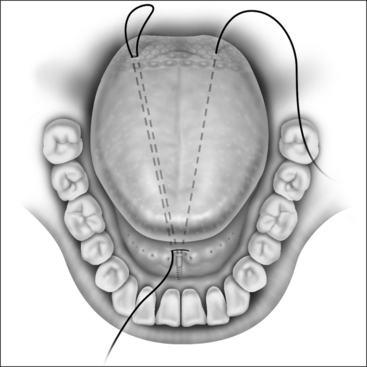

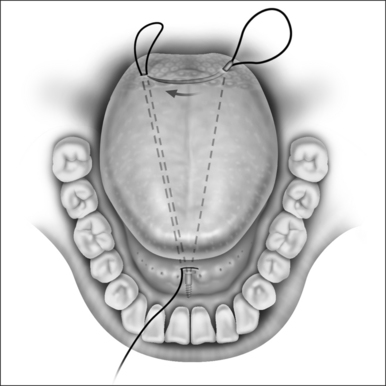

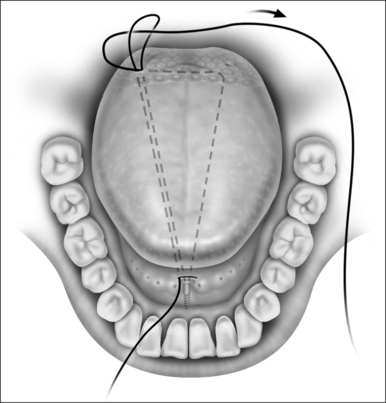

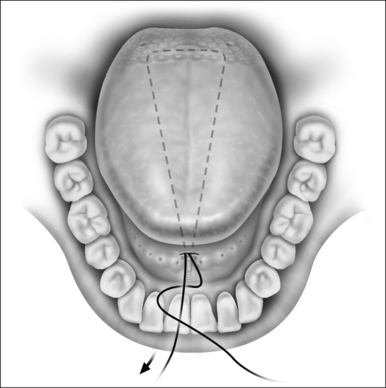

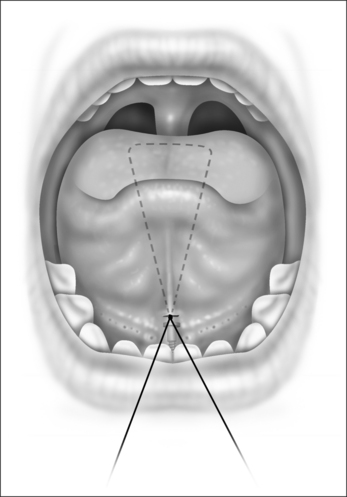

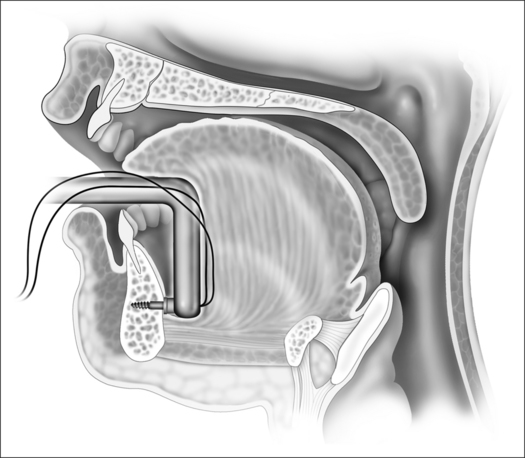

The principle is based on passing a non-absorbable Prolene suture through the tongue in an inverted triangle, with the apex at the inner table of the mandible, and the base of the triangle at the base of tongue region. The suture acts as a sling or hammock that creates a dimple at the base of tongue and prevents the tongue from falling posteriorly. The dimple in the base of tongue acts to allow a passage of air through, thus keeping the airway patent. This procedure is usually done in combination with a palate procedure and/or the hyoid myotomy.

Fig. 44.12 (Repose 2). Backward drilling device introducing the screw into the inner table of the mandible.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

Intraoperative intravenous dexametasone is administered to all patients undergoing the tongue base procedure. Perioperative use of nasal CPAP is strongly encouraged. Patients who undergo multilevel surgery for OSA are monitored in the high-dependency unit overnight. All patients should be monitored closely in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for at least 4 hours postoperatively. Many authors believe that the postoperative complications are low, but if they were to occur, they would occur within the first 3 hours.5,9,10

5 SUCCESS RATES OF THE PROCEDURES

5.1 GENIOGLOSSUS ADVANCEMENT AND HYOID MYOTOMY

These two procedures are frequently done together and hence, most data are of these two procedures combined. Riley et al.25 were first to report a 60% success rate in 133 patients who underwent the combined UPPP, genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy procedure. Riley et al.26 validated the hyoid procedure as a single operation in 15 patients who had failed UPPP, and found a success rate of 75%. Since the mid-1990s, many authors have reported a success rate of 60–70% for the multilevel procedures with UPPP, genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy procedure.25,27–29 Hormann et al.30 showed that there was significant increase in the retrolingual space after the hyoid suspension procedure. Neruntarat demonstrated an impressive 78% success rate for combined UPPP and hyoid suspension technique.31 He also showed a 70% success rate for combined UPPP, genioglossus advancement and hyoid suspension.32 Hormann et al.33 in 2004 revealed a 78.8% response rate (defined as a reduction of preoperative AHI by at least >20%) and 57.6% success rate (defined as a 50% reduction of preoperative AHI and <15) in 66 patients who underwent UPPP, hyoid suspension and some other form of tongue base procedure. A small prospective trial showed that genioglossus advancement and the tongue suspension method were useful in patients with severe OSA, with tongue suspension having a slight advantage.34 Verse et al.35 also had a 69.6% response rate in 46 patients who underwent the hyoid myotomy procedure. Baisch et al.36 in 2006 revealed an overall success rate (defined as a 50% reduction of preoperative AHI and <15) of 59.7% in 83 patients who underwent UPPP and the hyoid suspension procedure.

5.2 TONGUE SUSPENSION

The tongue suspension suture was first introduced in the late 1990s; the procedure showed promising results and improvements in both subjective and objective outcomes.37 Subsequent reports also revealed fair improvements in objective polysomnography results.38 Thomas et al.34 demonstrated that the success rate of the tongue suspension device was near 60%, and tongue suspension had a slight advantage over the genioglossus advancement procedure. Kuhnel et al.39 showed in 28 patients that while tongue suspension had benefits in both subjective and objective results, there were no obvious cephalometric changes noted postoperatively. Omur et al.40 had an impressive 81.8% success rate in 22 patients with severe OSA who had undergone a combined UPPP and tongue suspension procedure. Long-term follow-up at 3 years also showed impressive outcomes of a success rate of 78% in 55 patients with severe OSA.41

1. Terris DJ, Hanasono MM, Liu YC. Reliability of the Muller maneuver and its association with SDB. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1819-1823.

2. Cahali MB. Lateral pharyngoplasty: a new treatment for OSAHS. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1961-1968.

3. Pang KP, Woodson BT. Expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty: a new technique for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137:110–4.

4. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Practice parameters for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: the efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway. Sleep 1996;19;152–5.

5. Utley DS, Shin EJ, Clerk AA, et al. A cost-effective and rational surgical approach to patients with snoring, upper airwayresistance syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:726-734.

6. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(2):117-125.

7. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, et al. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in OSAS: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:117-125.

8. Fujita S, Woodson BT, Clark JT, et al. Laser midline glossectomy as a treatment of OSA. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:805-859.

9. Pang KP. Identifying patients who need close monitoring during and after upper airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120::60.

10. Terris DJ, Fincher EF, Hansonon MM, Fee WEJr, Adachi K. Conservation of resources: indications for intensive care monitoring after upper airway surgery on patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(6):784-788.

11. Pang KP. One-stage nasal and multilevel pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea: safety and efficacy. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(4):272-276.

12. Borowiecki BD, Sassin JF. Surgical treatment of sleep apnoea. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:506-512.

13. Fujita S. Surgical treatment of OSA: UPPP and lingualplasty (laser midline glossectomy). In: Guilleminault C, Partinen M, editors. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: Clinical Research and Treatment. New York: Raven Press; 1990:129-151.

14. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with OSAS. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

15. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. 2002;127:13-21.

16. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph NJ. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(3):454-459.

17. Pang KP, Terris DJ, Podolsky R. Severity of OSA: correlation with clinical examination and patient perception. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;. (in press)

18. Verse T, Joachim TM, Pirsig W. Effect of nasal surgery on sleep related breathing disorders. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:64-68.

19. Busaba NY. Same-staged nasal and palatopharyngeal surgery for OSA: is it safe? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:399-403.

20. Rubin AHE, Eliaschar I, Joachim Z, et al. Effects of nasal surgery and tonsillectomy on sleep apnoea. Bull Eur Physiopathol Respir. 1983;19:612-615.

21. Dayal VS, Phillipson EA. Nasal surgery in the management of OSA. Ann Otol Laryngol. 1985;94:550-554.

22. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Inferior sagittal osteotomy of the mandible with hyoid myotomy suspension: a new procedure for OSA. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:589-593.

23. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. OSA and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:717-721.

24. Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. The hypopharynx: upper airway reconstruction in OSAS. In: Fairbanks DNF, Fujita S, editors. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994:193-209.

25. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108(2):117-125.

26. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111(6):717-721.

27. Hendler BH, Costello BJ, Silverstein K, Yen D, Goldberg A. A protocol for uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, mortised genioplasty, and maxillomandibular advancement in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an analysis of 40 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(8):892-897.

28. Silverstein K, Costello BJ, Giannakpoulos H, Hendler B. Genioglossus muscle attachments: an anatomic analysis and the implications for genioglossus advancement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90(6):686-688.

29. Vilaseca I, Morello A, Montserrat JM, Santamaria J, Iranzo A. Usefulness of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with genioglossus and hyoid advancement in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(4):435-440.

30. Hormann K, Hirth K, Erhardt T, Maurer JT, Verse T. Modified hyoid suspension for therapy of sleep related breathing disorders. operative technique and complications. Laryngorhinootologie. 2001;80(9):517-521.

31. Neruntarat C. Hyoid myotomy with suspension under local anesthesia for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260(5):286-290. Epub 2002 Dec 5.

32. Neruntarat C. Genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy under local anesthesia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(1):85-91.

33. Hormann K, Maurer JT, Baisch A. [Snoring/sleep apnea – surgically curable]. HNO. 2004;52(9):807-813.

34. Thomas AJ, Chavoya M, Terris DJ. Preliminary findings from a prospective, randomized trial of two tongue-base surgeries for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(5):539-546.

35. Verse T, Baisch A, Hormann K. [Multilevel surgery for obstructive sleep apnea. Preliminary objective results]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2004;83(8):516-522.

36. Baisch A, Maurer JT, Hormann K. The effect of hyoid suspension in a multilevel surgery concept for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(5):856-861.

37. Woodson BT, Derowe A, Hawke M. Pharyngeal suspension suture with repose bone screw forobstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(3):395-401.

38. Woodson BT. A tongue suspension suture for obstructive sleepapnea and snorers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(3):297-303.

39. Kuhnel TS, Schurr C, Wagner B, Geisler P. Morphological changes of the posterior airway space after tongue base suspension. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(3):475-480.

40. Omur M, Ozturan D, Elez F, Unver C, Derman S. Tongue base suspension combined with UPPP in severe OSA patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(2):218-223.

41. Vicente E, Marin JM, Carrizo S, Naya MJ. Tongue-base suspension in conjunction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea: long-term follow-up results. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1223-1227.