CHAPTER 13 Multidirectional Instability of the Glenohumeral Joint

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder is usually an atraumatic condition in which the shoulder demonstrates symptomatic laxity in more than one direction. MDI was first described in 1980 by Neer and Foster.1 They reported on a group of patients who had pain and laxity in the anterior, posterior, and inferior directions. They successfully eliminated the symptoms in most patients using an open inferior capsular shift procedure based on the humerus. Duncan and Savoie2 described the first arthroscopic treatment of MDI in a pilot study using a modification of the Caspari transglenoid capsular shift technique, and many surgeons have expanded and improved on this original idea.

Several reports have been published showing excellent results with arthroscopic treatment of the patient with multidirectional instability. In their initial report, Duncan and Savoie2 found that patients showed improvement at 1- to 3-year follow-up. The average postoperative Bankart score was 90 and all had a satisfactory score according to the Neer system.

Wichman and Snyder3 have reported results of arthroscopic capsular shift for MDI in 24 patients with an average age of 26 years and a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Five patients (21%) had an unsatisfactory rating according to the Neer system. Of the unsatisfactory cases, one patient was in litigation for a motor vehicle accident and there were three workers’ compensation cases.

Treacy and Savoie4 have reported on 25 patients with MDI of the shoulder who underwent an arthroscopic capsular shift. At an average 5 year follow-up, three patients had episodes of subluxation but none had recurrent dislocation. According to the Neer system, 88% of patients had satisfactory results.

Gartsman5 has reported on 47 patients who underwent arthroscopic capsular plication for MDI. Of these patients, 94% had good to excellent results at an average follow-up of 35 months, and 85% of athletes returned to their desired level of participation.

Lyons and colleagues6 have shown favorable results with an arthroscopic laser-assisted technique, in which the rotator interval was plicated with multiple sutures. Of 27 shoulders, 26 remained stable at 2-year follow-up, and 86% of athletes returned to their sport at the same level.

McIntyre and associates7 have reported results of arthroscopic capsular shift in MDI patients using a multiple suture technique in the anterior and posterior capsules, with 32-month follow-up. Recurrent instability occurred in 1 patient (5%), who was treated successfully with a repeat arthroscopic stabilization; 13 athletes (93%) returned to their previous level of performance.

Hewitt and coworkers8 have demonstrated favorable techniques and results in a review article of multidirectional instability of the shoulder using a pancapsular plication suture technique.

Tauro and Carter9 have reported preliminary results of a modified arthroscopic capsular shift for anterior and anterior-inferior instability in four patients, with a minimum follow-up of 6 months. No patients developed recurrent instability in this short-term follow-up period.

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

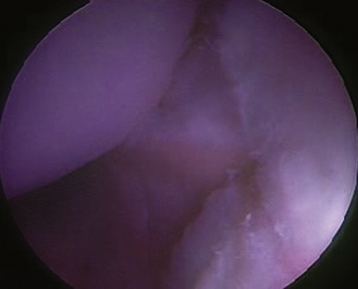

In MDI patients, there is an increased laxity of the joint capsule. Some patients acquire this laxity with activity and other patients have congenitally lax tissues. The most common surgical finding is a lax inferior capsule. The deficiency of the anterior and posterior pouches will differ among patients. There will be poorly defined bands of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) in the anterior pouch, posterior pouch, or both. The rotator interval will exhibit significant laxity and present with a bulged-out appearance. The rotator interval contains the coracohumeral ligament, superior glenohumeral ligament, and joint capsule. A drive-through sign signals the ability to move the arthroscope easily under the humeral head into the axillary pouch and is produced by laterally distracting the humerus. This is a common finding in patients with MDI. Viewing the shoulder from the posterior portal, a skybox view sign is present if the entire posterior sulcus is easily visualized.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Evaluate the range of motion of the other extremities and check for hyperelasticity of the knees, elbows, and metacarpophalangeal joints. Note any and all joints that exhibit hyperextension and/or hypermobility.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Imaging modalities that are most commonly used are plain radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Plain radiographs are often normal, but should be evaluated for any bony deficiency of the glenoid or humeral head. MRI scans are often used in the evaluation of the patient with MDI. An MRI with intra-articular contrast is most helpful. The choice of contrast agent depends on the radiologist, and normal saline appears to be the safest agent used. A typical MRI finding is a large capsular volume. Often, a large axillary fold is noted. The appearance is that of an upside-down bubble in the coronal view, extending inferiorly below the glenoid. One pathognomonic hallmark of MDI, as described by Neer,1 is bulging of the rotator interval with contrast material. If there is significant rotator interval laxity, one might see the entire intra-articular portion of the biceps tendon silhouette. The underside of the rotator cuff and rotator interval may have space between them and the biceps tendon in the coronal sections. The axial sections will show capsular laxity in the anterior and posterior sides of the joint, usually in the lower sections of the glenoid. Evaluate the scan for any signs of labral degeneration, tears, or malformation. Always try to determine the integrity of the rotator cuff. Evaluate for any cysts in the spinoglenoid notch.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Arthroscopic Treatment

Instruments, Equipment, and Implants

Gravity or pump inflow may be used during the because of, but flow and pressure levels should be kept low to prevent excessive tissue swelling. A series of free sutures are also necessary. Additionally, some small-diameter glenoid anchors should be available in case of an unexpected labral tear or deficient labrum.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Arthroscopic Capsular Shift

Arthroscopy offers several advantages over open surgery in the management of MDI. The ability to detect injuries and abnormalities under magnification extends our diagnostic capability and allows direct repair of abnormal or injured structures on all sides of the joint. Diagnostically, one can obtain an overview of the joint, detecting the presence of labral tears, capsular tears, and capsular and rotator interval laxity. Although the surgeon will already know the direction of the instability by the history and physical examination, with the patient awake and under anesthesia, repeating the examination while visualizing the movement with the arthroscope in the joint is useful (Fig. 13-1). The usual advantages of arthroscopy include preservation of muscle attachment, better visualization of pathology, anatomy-specific repairs based on this visualization, and small incisions. Patients usually experience less pain postoperatively by virtue of the minimally invasive nature of the procedure.

An interscalene block and catheter are routinely used for intraoperative and postoperative pain relief. This should be placed under ultrasound guidance and with the help of a nerve stimulator to avoid complications by an anesthesiologist with experience in regional anesthesia. Several methods are used today.10,11 Because of reported complication rates, avoid intra-articular pain pumps, but an indwelling interscalene catheter is currently thought to be acceptable.

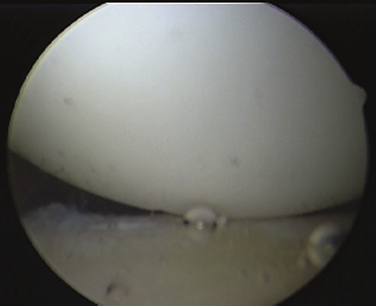

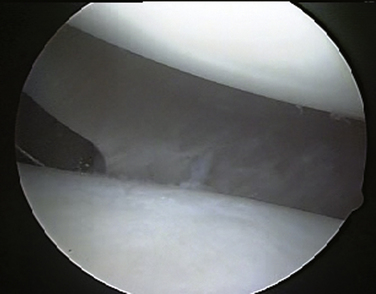

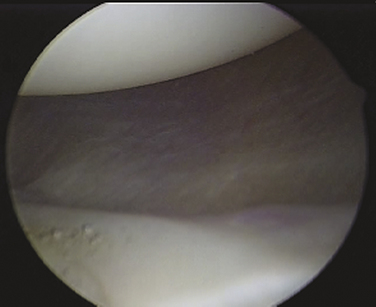

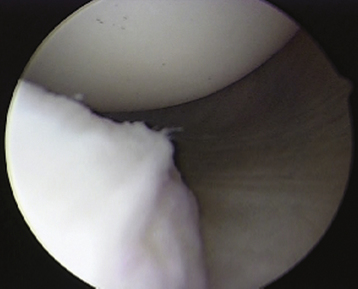

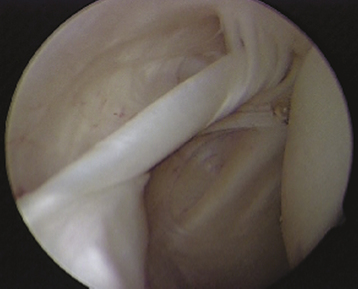

Once adequate anesthesia, positioning, prepping, and draping have been carried out, the diagnostic arthroscopy can begin. The lateral decubitus position offers an ergonomic advantage when doing labral and capsular reconstructions of the shoulder; however, if one has no experience with this position, the beach chair position can be used. The diagnostic arthroscopy should begin with the standard posterior portal at the horizon of the glenohumeral joint. Several areas need to be evaluated, including the anterior capsule (Fig. 13-2), inferior capsule or axillary pouch (Fig. 13-3), posterior capsule (Fig. 13-4), rotator interval (Fig. 13-5), labrum, and rotator cuff. In some patients with MDI, the posterior capsule may so thin that the muscle of the infraspinatus can be visualized through it (Fig. 13-6).

The attachment of the anterior and posterior capsule to the humerus should be visualized, looking for capsular splits, perforations, or humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions (Fig. 13-7).

Treatment of the Lax Capsule

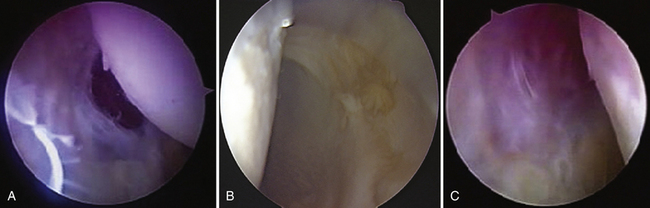

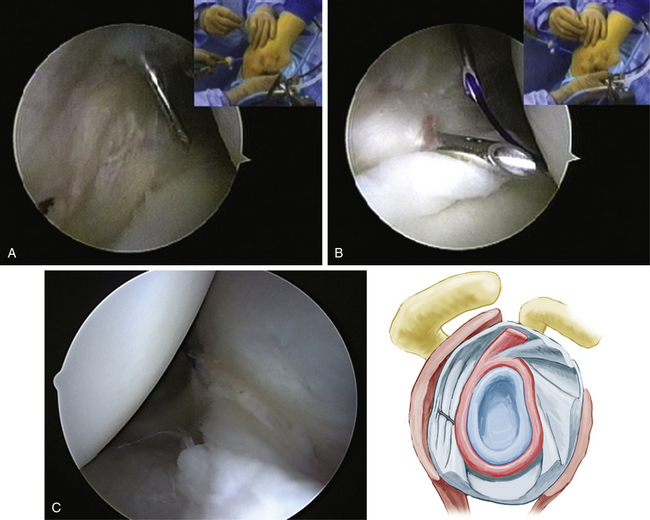

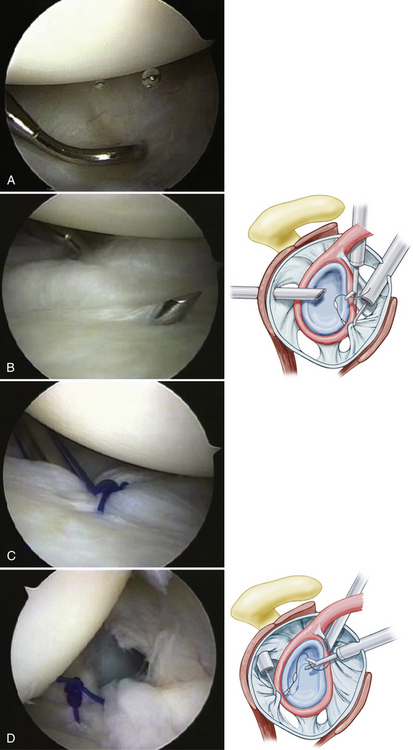

The initial step involves abrading the capsule to stimulate a healing response. A full-radius shaver, without teeth and used without suction, works well. Alternatively, a synovial rasp can be used to roughen up the capsule. The capsule can be left in situ or can be cut at its attachment to the labrum. A suture hook is then used to perforate the capsule approximately 1 cm from the labrum. The area to be initially penetrated is determined by the amount of capsular laxity. A standard approach is to draw an imaginary line parallel to the horizon of the glenoid toward the capsule. This is the point of entry for the suture hook into the capsule. For a left shoulder, the anterior capsule is addressed as follows. The first suture hook is placed in the capsule at the 6 o’clock position at the point of the imaginary line and rotated until it pierces the capsule (Fig. 13-8A). The entire capsule is then advanced superiorly until the capsule appears taut (usually the 7 o’clock position; see Fig. 13-8B). This is the point of advancement of the first suture. The same suture hook is then used to penetrate the labrum at the junction of the labrum and articular margin at that point (see Fig. 13-8C). A shuttle relay or some other monofilament suture is threaded through the suture hook. This suture is used to shuttle the final suture through both the capsule and labrum or, in some systems, the permanent suture can be passed. If a PDS suture has been passed, it can simply be tied around the suture tail that will be retrograded. As the suture is tied, take care to ensure that the post limb of the suture is the limb passing through the capsule so that the knot is placed away from the articular surface. I prefer a sliding self- locking (modified Roeder) knot. All knots have a tendency to migrate toward the articular margin as they are being tightened, so you must be cognizant to push the knot away as the suture and capsule are tightened. This advances the capsule superiorly and medially.

FIGURE 13-8 A, In this view of a right shoulder from the posterior portal, the inferior capsule is penetrated by a suture hook in preparation for capsular plication. B, The hook is then moved superiorly at least 1 “hour” and then placed between the labral bone junction (left to right). C, The suture is then passed through both the capsule and labrum and tied arthroscopically, plicating the capsule. D, The posterior capsule is plicated in similar fashion, as demonstrated in this view from the anterior portal.

These steps are repeated up the face of the glenoid. The second capsular stitch is placed often at the 7 o’clock position and advanced until it is taut, which is usually near the 8 o’clock position on the glenoid. Additional sutures are placed in a similar manner up the glenoid face until the entire anterior capsular laxity is eliminated (Fig. 13-9).

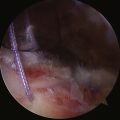

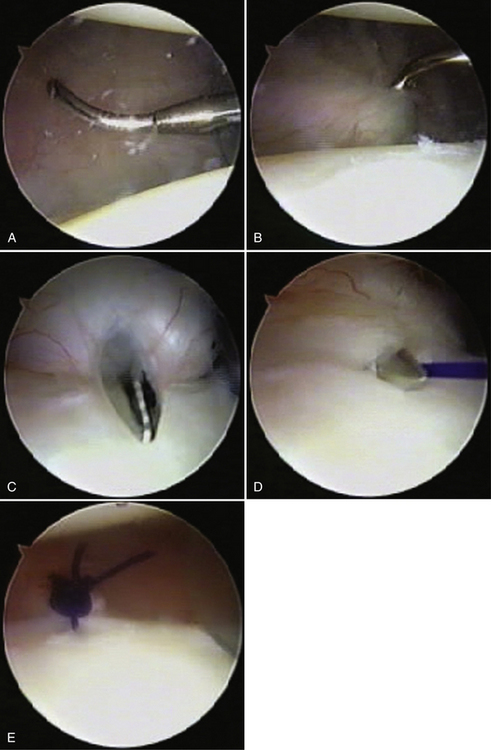

The posterior capsule is addressed in a similar way. For a left shoulder, start at the 6 o’clock position and shift the capsule superiorly until it is taut (usually around the 5 o’clock position) using the same technique described for the anterior procedure (see Fig. 13-8D). Continue superiorly along the length of posterior glenoid until all capsular redundancy is eliminated (Fig. 13-10).

FIGURE 13-10 A, The lax posterior capsule has been rasped and the suture hook is preparing to penetrate the distal end of the valley of the loose capsule. B, The suture hook is advanced through the tissue and the superior shift is initiated. C, The suture hook is advanced and placed between the labrum and bone of the glenoid. D, The suture is advanced through all the plicated structures in preparation for repair. E, The sutures are then tied, creating a capsular tuck.

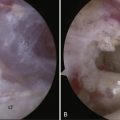

Often in MDI, the posterior capsule is insufficient to hold a plication suture. In these cases, one may use a suture plication technique that includes the infraspinatus tendon. For this technique, the lateral capsule is pierced percutaneously with a large-lumen, 18-gauge spinal needle inferiorly near the capsular insertion into the humerus (Fig. 13-11A). A suture is threaded through the needle into the joint (see Fig. 13-11B). The initial stitch should be around the 7 o’clock position for a right shoulder and the 5 o’clock position for a left shoulder. The suture coming through the needle is grasped and the spinal needle is removed. A suture retrieval device is used to pierce the capsule adjacent to or just under the labrum, grasping the percutaneously placed suture. It is then removed out the posterior portal. The cannula is retracted until it lies just outside the infraspinatus tendon. Using a switching stick, the cannula is placed into the subacromial space. A crochet hook is used to grab the suture blindly while watching from inside the joint. One should see the cannula indenting the infraspinatus during this retrieval. This suture is tied and the degree of capsular tightening is assessed (Fig. 13-11C). These steps are repeated until sufficient laxity has been eliminated. In most cases, two to four sutures will be required.

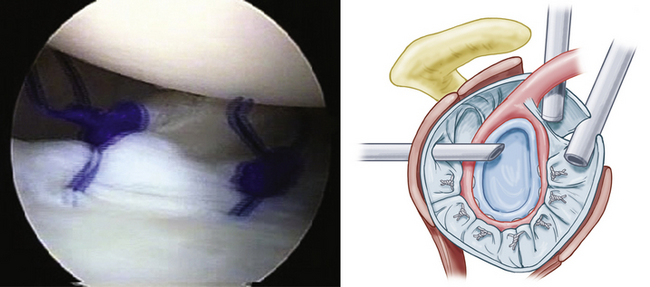

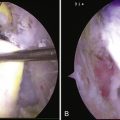

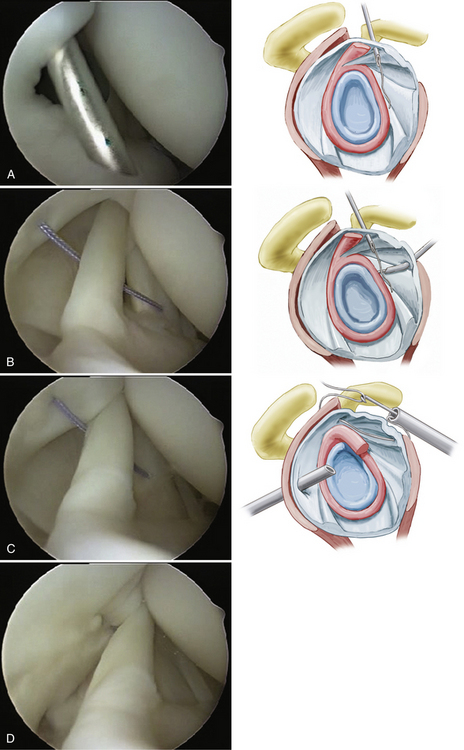

The arthroscope is then placed posteriorly above the level of the reconstruction and the rotator interval is assessed. In cases of MDI, true closure of the rotator interval is required to complete the stabilization of the shoulder. To tighten both the inner and outer layers of the rotator interval, a spinal needle is placed into the joint percutaneously approximately 1 cm from the articular margin, just anterior to the edge of the supraspinatus tendon (Fig. 13-12A). A suture is threaded through the needle into the joint and placed anteriorly for retrieval. The anterior cannula is then retracted out of the joint until it is just anterior to the subscapularis tendon and the outer layer of the rotator interval. A suture retrieval device is placed through the anterior layer of the rotator interval tissue and through the capsule entering the joint. The upper border of the subscapularis tendon should be incorporated in true MDI cases. The suture passed percutaneously is then grasped and pulled out the anterior cannula (see Fig. 13-12B). A switching stick is then used to pass the cannula around the subscapularis tendon into the subacromial space. The cannula should be seen indenting the supraspinatus from inside the joint; it is then retracted until the indention is just anterior to the suture. A crochet hook is to blindly grasp the suture blindly from the subacromial space and retrieve it out the anterior cannula as well (Fig. 13-12C). A sliding locking knot is used to close the interval (see Fig. 13-12D). Additional sutures may be needed and are placed in the same manner. Work progressively more medially with each additional stitch. Alternatively, one may look in the subacromial space to retrieve and tie the suture, being careful not to incorporate the coracoacromial ligament into the rotator interval closure. When you see minor internal rotation of the arm, there has been adequate closure of the rotator interval.

FIGURE 13-12 Technique of true rotator interval placation. A, A spinal needle is placed through the supraspinatus and superior capsule 1 cm medial to its attachment to the humeral head. B, The suture is retrieved through the subscapularis and outer rotator interval. C, The suture is blindly retrieved from the subacromial area. D, The suture is tied, plicating the rotator interval and shortening the coracohumeral and superior glenohumeral ligaments.

Treatment of the Torn Capsule and Special Techniques

Some patients with MDI may have associated labral or capsular tears, especially if they have had repeated subluxations or dislocations. In these patients, it is important to remember to address the lax capsule in addition to the torn labrum. The labrum is repaired using suture anchors, preferably double-loaded anchors. The first suture from the anchor is placed through the capsule inferior to the tear and advanced superiorly under the free edge of the labral tear. This achieves a superior capsular shift and labral repair in one step. It is a good technique to mattress the sutures for greater tissue movement when possible. The second suture from the anchor can achieve more shift of the capsule when needed, or simply be placed around the first stitch to hold the shifted tissue in place and help secure the labral tear. The placement of the anchor and suture depends on the location of the tear. Once the labrum has been re-established and the capsule has been shifted superiorly, additional capsular plication stitches can be added to shift the lax capsule further in a manner similar to what has already been described. Once the labral repair and capsular shift are completed, the rotator interval can be addressed.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

PITFALLS

POSTOPERATIVE PROTOCOLS

Treatment Regimen

Once the capsular reconstruction has healed, based on the clinical end point examination and progressively decreasing pain, and the patient is able to maintain correct scapular position, the therapy is progressed to include rotator cuff–strengthening exercises, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation exercises, and plyometrics. No passive stretching is allowed by the therapist for the first 3 months. At 4 to 8 months postoperatively, integrated rehabilitation as described by Kibler12 is initiated, along with sports-specific conditioning in the athletic population. Sports are allowed between 6 and 12 months, depending primarily on shoulder position and tracking patterns.

Avoiding Complications

If a knot is left adjacent to the articular surface, a patient may complain of clicking with shoulder range of motion. The long-term effect of this is unknown. Be sure to push the knots away from the articular surface when possible.

The most devastating complication is chondrolysis, which has been associated with thermal devices and intra-articular pain pumps.13,14 Avoid their use to minimize risk.

1. Neer CS, Foster CR. Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:897-908.

2. Duncan R, Savoie FH Arthroscopic inferior capsular shift for multidirectional instability of the shoulder: a preliminary report. Arthroscopy, 9; 1993:24-27.

3. Wichman MT, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic capsular plication for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1997;5:238-243.

4. Treacy SH, Savoie FH. Arthroscopic treatment of multidirectional instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:345-350.

5. Gartsman GM, Roddy TS, Hammerman SM Arthroscopic treatment of multidirectional glenohumeral instability: 2 to 5 year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 17; 2001:236-243.

6. Lyons TR, Griffith PL, Savoie FH. Laser-assisted capsulorrhaphy for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:25-30.

7. McIntyre LF, Caspari RB, Savoie FH The arthroscopic treatment of multidirectional shoulder instability: two-year results of a multiple suture technique. Arthroscopy, 13; 1997:418-425.

8. Hewitt M, Getelman MH, Snyder SJ Arthroscopic management of multidirectional instability: pancapsular plication. Orthop Clin North Am, 34; 2003:549-557.

9. Tauro JC, Carter FM. Arthroscopic capsular advancement for anterior anterior-inferior shoulder instability. A preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:513-517.

10. Soeding PA, Sha S, Royse CE, et al. A randomized trial of ultrasound-guided brachial plexus anesthesia in upper limb surgery. Anaesth Intens Care. 2005;33:719-725.

11. Reuben SS. Interscalene block superior to general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:207.

12. Kibler WB. Rehabilitation of the shoulder. In: Kibler WB, Herring SA, Press JM, editors. Functional Rehabilitation of Sports and Musculoskeletal Injuries. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen Publishers; 1998:149-170.

13. Levine WN, Clark AN, D’Allessandro DF, Yamaguchi K Chondrolysis following arthroscopic thermal capsulorraphy to treat shoulder instability: A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 87; 2005:616-621.

14. Petty DH, Jazwari LM, Estrada LS, Andrews JR Glenohumeral chondrolysis after shoulder arthroscopy: case reports and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med, 32; 2004:509-515.