Chapter 58 Multi-modality management of nasopharyngeal stenosis following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

1 INTRODUCTION

Nasopharyngeal stenosis (NPS) after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is a serious problem. More palatal procedures are being performed leading to an increased incidence of nasopharyngeal stenosis, but little has been written about this severe complication and its management.

Historically, adult NPS was a consequence of maxillofacial trauma or severe infection such as syphilis. Now NPS is seen as a complication of surgery such as tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in the pediatric population, and UPPP in the adult population with obstructive sleep apnea. Rhinoscleroma, lupus, diphtheria, tuberculosis, acid burn, scarlet fever and aggressive velopharyngeal repair can also cause nasopharyngeal stenosis.1,2

The complication of severe nasopharyngeal stenosis following UPPP is well understood. Most cases are problems of surgical technique. The management of intraoperative or postoperative bleeding with nasopharyngeal packing and electrocautery is an important cause of NPS. Adenoidectomy in conjunction with UPPP carries an increased risk of nasopharyngeal stenosis. Other technical errors include excessive excision and cauterization of the posterior tonsillar pillars or undermining the posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls. Wound dehiscence, infection, necrosis and scarring in keloid-forming patients are some other causes of acquired NPS. Also, the use of KTP (potassium titanyl phosphate) laser to perform adenoidectomy is associated with an extremely high incidence of NPS.1

2 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

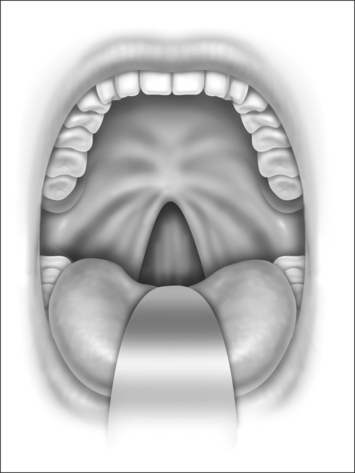

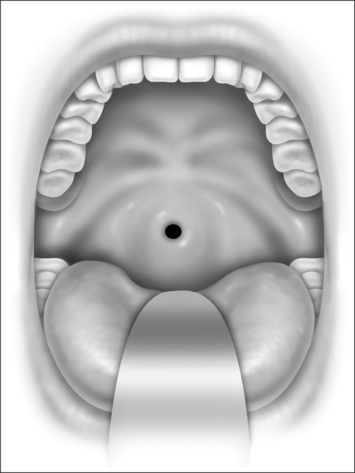

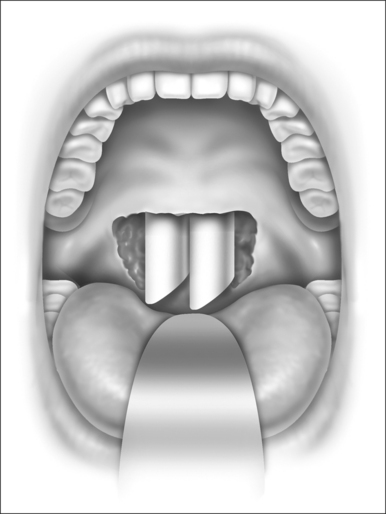

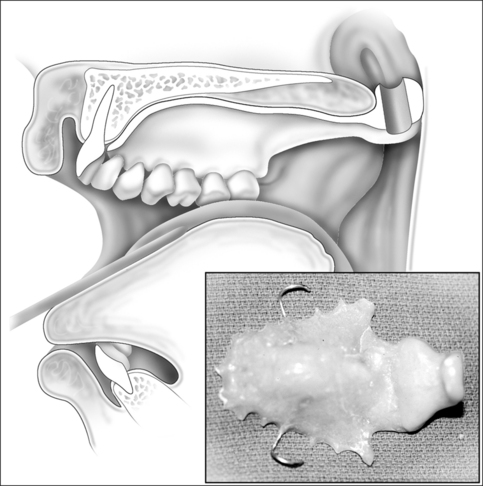

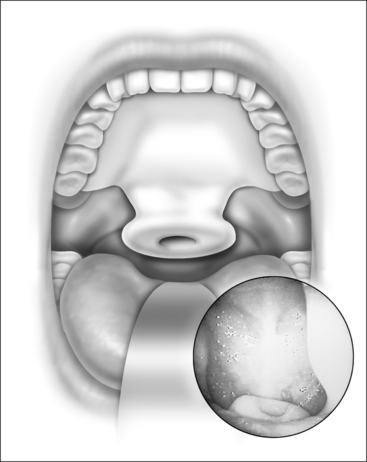

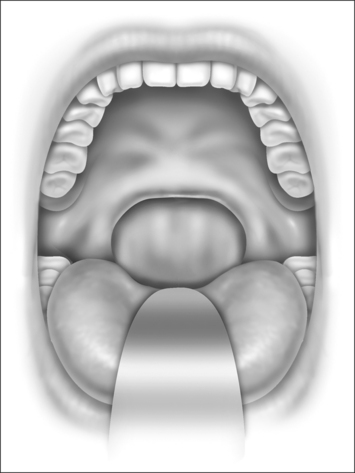

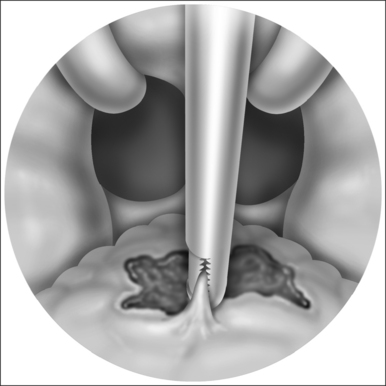

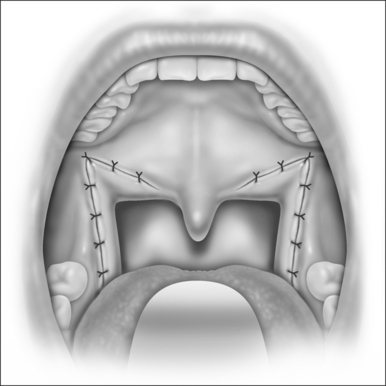

Nasopharyngeal stenosis is graded as type I (mild) when the lateral aspects of the palate adhere to the posterior pharyngeal wall. Type II (moderate) is the occurrence of circumferential scarring with small central opening of the soft palate. This circumferential opening is between 1 and 2 cm in diameter. Type III (severe) is when the entire palate fuses with the posterior and lateral palatal wall, leaving a residual opening less than 1 cm (Fig. 58.1&). Treatment for type I stenosis can be carried out as an outpatient, whereas treatment for type II and III stenosis may require general anesthesia in an inpatient setting. CO2 laser is used in conjunction with a scanning device at 30 watts, with a pharyngeal handpiece in a continuous mode in type I patients. During surgery, two nasopharyngeal tubes (size 6 or 7) are passed and left in place for 3–4 days as temporary stents (Fig. 58.2). A customized nasopharyngeal obturator is used in type II and III patients and inserted after removal of the stents on the third or fourth postoperative day (Figs 58.3 and 58.4). The nasopharyngeal obturator consists of an upper dental appliance with a customized nasopharyngeal extension as an obturator to stent open the nasopharynx. The patients use the stent during the day and remove it at night. The stent is left in place for 3–6 months (Fig. 58.5).

3 DISCUSSION WITH RESULTS ANDALTERNATIVE TREATMENT OPTIONS

UPPP remains the most commonly performed surgical treatment for obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. NPS is a severe complication of UPPP, though its incidence is not known. The incidence of severe type II and type III is estimated to be under 1%. Factors that increase the incidence of NPS include postoperative bleeding, infection, overheated tissues by the use of KTP laser, over-resection or excessive undermining of lateral pillars and combination of adenoidectomy with UPP. No uniform risk factors or surgical errors have been identified in our study.

The type I stenosis is treated under local anesthesia in an office setting using CO2 laser without the use of a nasopharyngeal obturator. Moderate and severe cases of NPS are treated in the operating room under general anesthesia. Most of these patients require prolonged use of the nasopharyngeal obturator. The obturator used has been custom designed by the senior author to treat severe cases of nasopharyngeal stenosis. The nasopharyngeal obturator consists of a standard dental obturator, which is constructed after a dental impression has been taken, and a nasopharyngeal extension with an airway to fill the neo-nasopharynx. This nasopharyngeal extension is contoured to the shape of the neo-nasopharynx using a drill after surgery to tightly fit the neo-nasopharynx after temporary stents have been removed. Use of the nasopharyngeal obturator in conjunction with CO2 laser led to a patent nasopharynx (defined for the purpose of this study as a nasopharyngeal opening of greater than 3 cm with no bands between the lateral pharyngeal wall and the palate in all patients.

References And Further Reading

1. Giannoni C, Sulek M, Friedman EM, et al. Acquired nasopharyngeal stenosis – a warning and a review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:163-167.

2. McLaughlin KE, Jacobs IN, Todd NW, et al. Management of nasopharyngeal stenosis in children. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1322-1331.

3. Krespi YP. Laser assisted uvulopalatoplasty – result and complications in 1000 patients. In: Krespi YP, editor. Office-Based Surgery of theHead and Neck. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:147-153.

4. Coleman JA, Van Duyne J. Treatment of nasopharyngeal inlet stenosis following uvulopalatoplasty with the CO2 laser. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:914-918.

5. Randall DA, Hoffer ME. Complications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:61-68.

6. Fairbanks DNF. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty complications and avoidance strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:239-245.

7. Katsantonis GP, Friedman WH, Krebs FJ, et al. Nasopharyngeal complications following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:309-314.

8. Croft CB, Golding-Wood DG. Uses and complications of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. J Laryngol Otol. 1990;104:871-875.

9. Ingrams DR, Spraggs PD, Pringle MB, et al. CO2 laser palatoplasty: early results. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:754-756.

10. Stepnick DW. Management of total nasopharyngeal stenosis following UPPP. Ear Nose Throat J. 1993;72:86-90.

11. Kazanjian VH, Holmes EM. Stenosis of the nasopharynx and its correction. Arch Otolaryngol. 1946;44:376-386.

12. Cotton RT. Nasopharyngeal stenosis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:146-148.

13. Correa AJ, Reinisch L, Sanders DL, Huang S, Deriso W, Duncavage JA, Garrett CG. Inhibition of subglottic stenosis with mitomycin-C in the canine model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108(11 Pt 1):1053-1060.

14. Holland BW, McGuirt WFJr. Surgical management of choanal atresia: improved outcome using mitomycin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(11):1375-1380.