CHAPTER 11 Müller’s Muscle–Conjunctival Resection–Ptosis Procedure Combined with Upper Blepharoplasty

Patients often present for cosmetic rejuvenation of the upper periorbita and the examination reveals both dermatochalasis and upper eyelid ptosis. In these situations it is both possible and preferable, to combine an upper blepharoplasty with ptosis surgery. Although this technique is commonly performed through an external approach with levator aponeurosis advancement or resection, many cosmetic surgeons do not appreciate the possibility of combining an internal Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection with an external upper blepharoplasty, especially when the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle are excised and an eyelid crease is reconstructed.

The Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis procedure, described in 1975 by Putterman and Urist, is a technique in which Müller’s muscle in the upper eyelid is partially resected and advanced.1 The exact mechanism by which the correction of ptosis is achieved is probably due to a number of effects that include resection and advancement of Müller’s muscle as well as the secondary effects of advancing the levator aponeurosis to the superior tarsal border. The classic approach to the treatment of a variety of lid ptosis presentations has been mostly through variations of an external (skin-muscle incision) approach through the upper eyelid crease whereby the anatomic ‘defect’ is visualized and presumably repaired (see Chapter 10). This approach, however, more often requires the cooperation of the patient during the surgical procedure and heralds a host of potential variabilities that include, but are not limited to, sedative effects, local anesthetic effects, edema, and performance anxiety on both the patient’s and surgeon’s part. To the contrary, the Müller’s muscle conjunctival resection can be performed with continuous IV sedation or even general anesthesia as it does not require intraoperative patient cooperation. The procedure is used to treat a variety of upper eyelid ptosis and can be combined with an upper blepharoplasty with or without crease reconstruction via a skin flap or a skin-muscle flap approach. The procedure has the many advantages over other ‘posterior approach’ lid ptosis procedures and the external approaches that includes the preservation of upper eyelid tarsus (which creates less risk of suture-induced keratopathy and theoretically preserves structural and functional aspects of the upper eyelid), repositions the elevated (involutional) eyelid crease to a lower positioned and more youthful level, and can more predictably improve upper eyelid position (MRD) and contour. In addition, the usual skin-muscle and fat excision that is performed for a host of reasons, including adequate exposure to the levator aponeurosis (that can be volume depleting to the upper eyelid), can be avoided if desired. There also is rarely a need for additional surgery to treat residual ptosis or overcorrections. This procedure that was originally felt to be effective mostly in individuals with only mild to moderate upper eyelid ptosis and/or had a positive response to neosynephrine eye drops, can in fact be applied in most all types of ptosis presentations.

Diagnosis and preoperative evaluation

MRD1 test

The MRD1 measurement is used to assess the upper eyelid levels (see Chapter 3, Fig. 3-8). It should be performed both before and during the phenylephrine test.

Phenylephrine test

Side effects, such as myocardial infarction and hypertension, have been reported after instillation of phenylephrine drops,2 but are exceedingly rare. Therefore, it is important to determine that the patient does not have a significant cardiac risk before the phenylephrine test is performed. In our collective experience this has, however, rarely posed a problem but if there is ever a significant concern then the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist should be consulted.

Glatt and Putterman3 have compared test results using 2.5 percent and 10 percent phenylephrine. It appears that both solutions are effective in determining candidates for the Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection procedure, but that the 2.5 percent solution may theoretically result in fewer vasoactive side effects. Our experience has been primarily with the 10 percent solution. Patients should be warned regarding the likely pupillary dilation after this test which may yield transient photophobia and visual blurring. If there is a history of glaucoma, it may be prudent to contact their ophthalmologist regarding any concerns of pupillary dilation. Finally, regarding other symptomatology after these tests, it is not uncommon for patients to experience transient ocular irritation that might relate to dryness or exposure symptoms and indicate to the surgeon the possibility of dry eye symptoms after surgery.

Surgical technique

Anesthesia

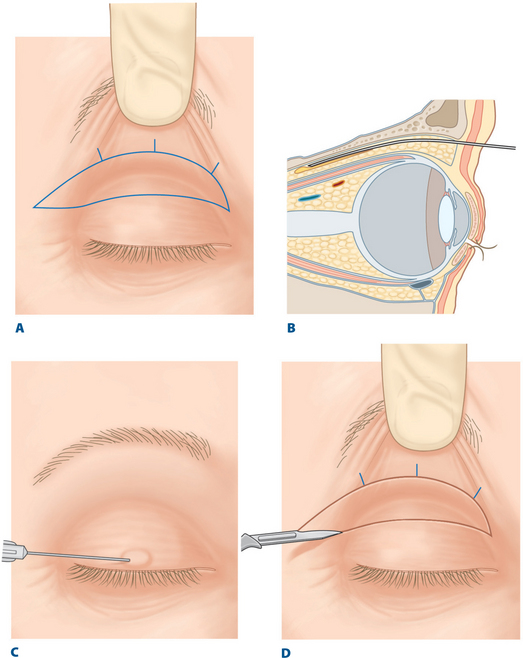

Local anesthesia is preferred in adults. The upper eyelid skin to be removed is marked according to the technique for upper blepharoplasty with crease reconstruction (see Chapter 7) or without crease reconstruction (see Chapter 8) (Fig. 11-1A). A frontal nerve block is used with local anesthesia to avoid swelling and bruising of the upper eyelid by local infiltration, which would make the operation more difficult and inexact.4

Figure 11-1 A, Outline of skin or skin and orbicularis oculi muscle to be excised.

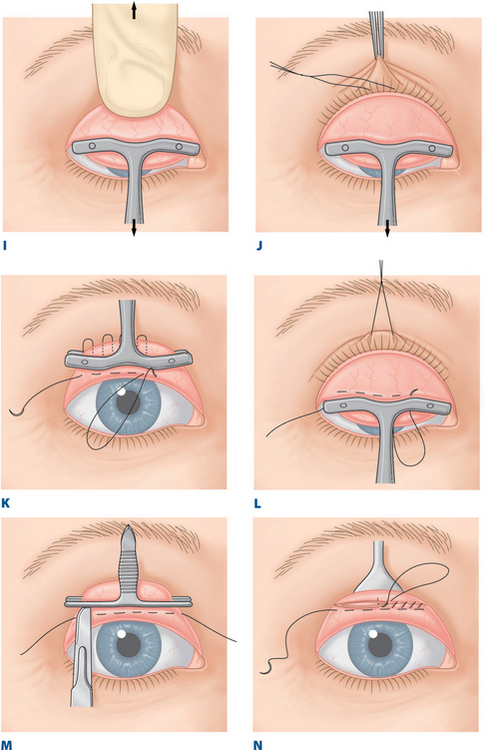

D, Scratch incision over marked upper eyelid.

I, Before locking the clamp, the surgeon slides out any entrapped tarsus.

P, Excision of outline ellipse of skin and orbicularis muscle with a disposable cautery.

Modified from Putterman AM, Fett DR: Müller’s muscle in the treatment of upper eyelid ptosis: A ten-year study. Ophthalmic Surg 1986; 17:354–356. With permission.

After the upper eyelid is marked for blepharoplasty and the chosen sedative is administered, a 23-gauge retrobulbar needle is inserted into the superior orbit, entering just under the midsuperior orbital rim lateral to the supra-orbital notch (Fig. 11-1B). The needle hugs the roof of the orbit during insertion until a depth of up to 4 cm is reached; then 1.5 ml of 2 percent lidocaine (Xylocaine) with epinephrine is injected. Alternately, bupivicaine (Marcaine) may be used to prolong the anesthetic effect. Another 0.5 ml of the anesthetic solution is injected subcutaneously over the central upper eyelid just above the lid margin (where a traction suture of 4-0 silk is placed), and a small amount may be injected under the lines marked on the upper eyelid (Fig. 11-1C).

Marking areas of excision and resection

A scratch incision is made over the marked upper blepharoplasty demarcations (Fig. 11-1D). A 4-0 black silk traction suture is inserted through skin, orbicularis muscle, and superficial tarsus 2 mm above the lashes at the center of the upper eyelid. Care must be taken to avoid a full thickness penetration with this maneuver and injury to the corneal surface. A medium-sized Desmarres lid retractor is used to evert the upper eyelid and to expose the palpebral conjunctiva from the superior tarsal border to the superior fornix. Topical tetracaine drops may be applied over the upper palpebral conjunctiva especially when light or no sedation is administered.

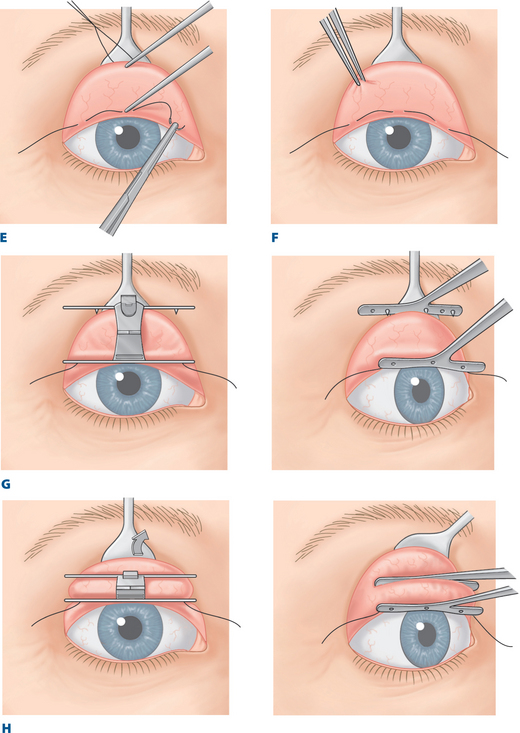

A caliper set at the determined amount of resection (i.e. 8.5 mm in a unilateral repair in those whose neosynephrine test restored the upper eyelid to the desired position), with one arm at the superior tarsal border, facilitates insertion of a 6-0 black silk suture through the conjunctiva 8.5 mm above the superior tarsal border (Fig. 11-1E). One suture bite centrally and two others approximately 7 mm nasal and temporal to the center mark the site. The preferred placement of the 6-0 black silk marking suture is 8.5 mm above the superior tarsal border (in those individuals with unilateral ptosis whose neosynephrine test brings them to a symmetric and satisfactory postion), but the suture may be placed 4.0–9.5 mm above the border if the response of the upper eyelid level to the phenylephrine test is slightly greater or less than desired. The smaller resections (in the 4.0–6.0 mm range) are typically more technically difficult to administer using the prescribed clamp, described below. The placement of this marking suture should be through conjunctiva only as penetration to and through Müller’s muscle may cause significant bleeding.

Separation of Müller’s muscle from the levator aponeurosis

A toothed forceps is used to grasp conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle between the superior tarsal border and the marking suture and to separate Müller’s muscle from its loose attachment to the levator aponeurosis (Fig. 11-1F). This maneuver is possible because Müller’s muscle is firmly attached to conjunctiva but only loosely attached to the levator aponeurosis (see Chapter 5).

Clamp application

Although this procedure can be performed with a variety of clamps and other instruments, it is much more easily and precisely performed with a particular instrument made for this procedure. One blade of this specially designed Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis clamp (Bausch & Lomb Storz Company, Manchester, MO) should be placed at the level of the marking suture. Each tooth of this blade engages each suture bite that passes through the palpebral conjunctiva (Fig. 11-1G).

The Desmarres retractor is then slowly released (with the handle of the retractor brought from the resting cephalad postion to a caudal position) as the other blade of the clamp engages conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle adjacent to the superior tarsal border (Fig. 11-1H).

Any entrapped tarsus is then released from the clamp with the surgeon’s finger (Fig. 11-1I). The clamp is compressed, and the handle is locked. This leads to the incorporation of conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle between the superior tarsal border and the marking suture.

The upper eyelid skin is pulled in one direction while the clamp is pulled simultaneously in the opposite direction (Fig. 11-1J). During this maneuver, the surgeon may feel a sense of attachment between the skin and the clamp. If this occurs, a greater amount of the levator aponeurosis may have been inadvertently trapped in the clamp. In this situation, the clamp should be released and reapplied into its proper position. This maneuver is possible because the levator aponeurosis sends extensions to orbicularis muscle and skin to form the lid crease (see Chapter 5).

Suturing and resection of conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle

With the clamp held straight up/vertically, a 5-0 double-armed plain catgut mattress suture is run 1.5 mm below the clamp along its entire width in a temporal to nasal direction in a horizontal mattress fashion, through the upper margin of the tarsus on one side and through Müller’s muscle and conjunctiva on the other side, and vice versa (Fig. 11-1K and L). The sutures are placed approximately 2–3 mm from each other. The surgeon uses a No. 15 surgical blade to excise the tissues held in the clamp by cutting between the sutures and the clamp. The knife blade is rotated slightly, with its sharp edge hugging the clamp (Fig. 11-1M).

The Desmarres retractor is used again to evert the eyelid while gentle traction is applied to the 4-0 black silk centering suture. The nasal end of the suture is then run continuously in a temporal direction; the suture passes should be about 2 mm apart through the edge of superior tarsal border, Müller’s muscle, and conjunctiva (Fig. 11-1N). Commonly, this suture just connects the edges of conjunctiva.

During continuous closure with the 5-0 plain catgut suture, the surgeon must be careful to avoid cutting the original mattress suture. This is facilitated by the surgeon’s using a small suture needle (S-14 Spatula, Ethicon) in addition to observing the mattress suture position during each suture bite during the conjunctival closure, and by the assistant’s applying continuous suction or swabbing with cotton-tip applicators along the incision edges. If the original horizontal mattress placement is too close to the clamp edge (within 1.5 mm or so) then this will be more difficult. The 5-0 plain catgut suture ends are passed through each side of the conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle before they exit through the temporal end of the incision (Fig. 11-1O). Once each arm of the suture reaches the temporal end of the eyelid, the suture ends are connected with a serrefine clamp. This is done to ensure that this suture is not inadvertently cut with the skin-muscle flap of the upper blepharoplasty procedure to follow and, if so, it can be more easily identified. Alternately, if a skin flap upper blepharoplasty (without muscle excision) is performed, the suture can be tied (described below) at this time.

Upper blepharoplasty

Several milliliters of same anesthetic solution is injected subcutaneously over the upper eyelids. Then an upper eyelid blepharoplasty is performed (as described in Chapters 7 and 8) through the steps of skin5 or skin and orbicularis muscle resection, excision of fat, and completion of hemostasis (Fig. 11-1P); however cautery should be minimized to avoid cutting the plain suture. If not already performed, the eyelid is again everted with a Desmarres retractor, the 5-0 plain catgut suture arms are tied with 4–5 knots, and the ends are cut close to the knot. In this way, the knot can be buried subconjunctivally, lessening postoperative keratopathy and surface irritation.

After this step, the crease sutures are placed and the skin is closed (see Chapter 7) (Fig. 11-1Q). If no crease is reconstructed, the skin is sutured at this time, as described in Chapter 8.

Postoperative care

Patients are observed postoperatively, as with blepharoplasty in general, to make sure that there is no excessive bleeding or possibility of retrobulbar hemorrhage, which has the potential for causing blindness. The patient applies cold compresses to the eyelids for the first 24 hours postoperatively. A topical antibiotic such as gentamicin (Garamycin) or a combination antibiotic/corticosteroid (TobraDex) ophthalmic ointment on the eye can be used once or twice a day for the first week or two. The patient may also use a sterile eyewash applied to cotton pads to wipe over the eyelids twice a day for 2 weeks after surgery. Patients are instructed for the first 2 weeks after surgery to bathe or shower only from the neck down and to wash their hair so as to avoid an abundant contact of soap and water with the eyes.

Results

In most patients with acquired ptosis (90 percent in the experience of AMP), the final eyelid level after treatment is within 2 mm of the opposite eyelid. In 88 percent of these treated eyelids, an MRD1 of 1.5–5 mm is achieved.6

Rarely, in less than 2 percent of patients, additional surgery may be required to treat residual ptosis. This is most often achieved with a levator aponeurosis procedure (see Chapter 10). However in rare situations an internal-approach resection may be repeated.

Alternative techniques

The Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection procedure has an advantage over the Fasanella–Servat procedure because it allows the tarsus to be preserved.7,8 This also carries less risk of suture keratopathy because the sutures are at the superior tarsal border instead of 3–4 mm closer to the eyelid margins, as in the Fasanella procedure. This operation is also superior to the levator aponeurosis advancement/resection procedures because results are much more predictable and there is less need for subsequent surgery.8,9

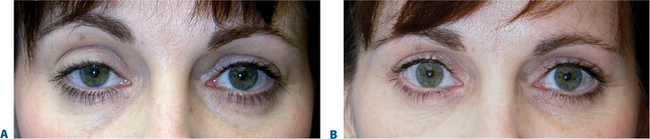

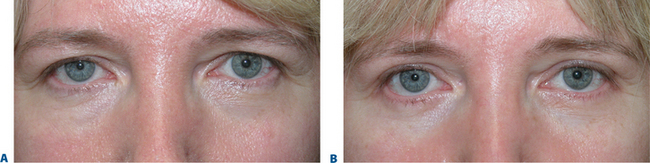

We have collectively performed this procedure on more than 2000 upper eyelids. In a report of results in 232 of the treated lids, 230 lids had levels that were considered cosmetically acceptable (Figs 11-2, 11-3, 11-4, 11-5, 11-6).6

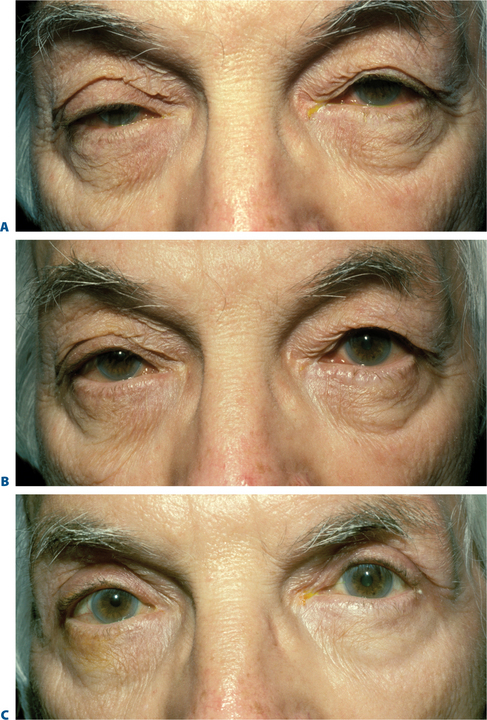

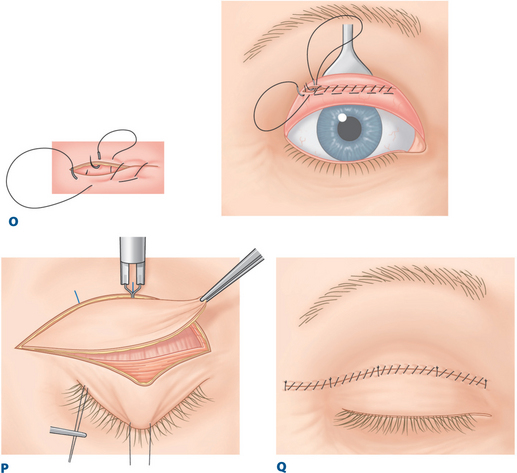

Figure 11-3 A, Preoperative appearance of a patient with upper eyelid ptosis associated with dermatochalasis and herniated orbital fat of all four eyelids. B, After instillation of phenylephrine in both upper fornices with elevation of eyelids to normal levels. C, After bilateral Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis procedure with excision of skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, and orbital fat from the upper eyelids and eyelid crease reconstruction. A lower eyelid external blepharoplasty using a skin-muscle flap approach (see Chapter 16) was performed simultaneously.

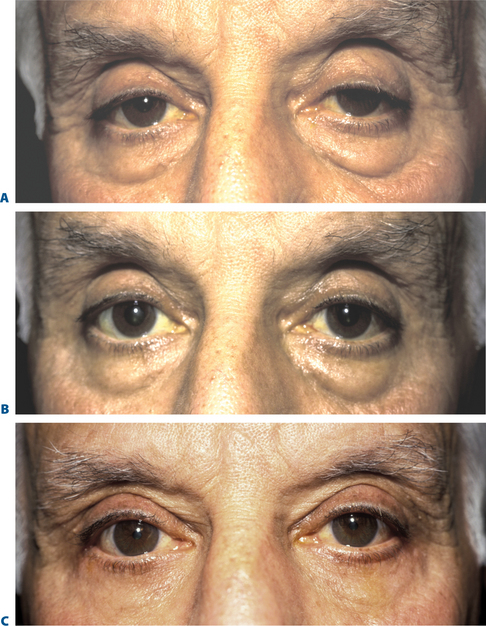

Figure 11-4 A, Preoperative appearance (oblique view to illustrate apparent volume/crease changes) of a patient with bilateral upper eyelid ptosis with associated dermatochalasis and herniated orbital fat of all four eyelids. B, After bilateral Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis procedure with excision of upper eyelid skin without orbicularis oculi muscle excision and medial orbital fat combines with lower blepharoplasty using a skin flap approach and lateral retinacular suspension canthoplasty (see Chapter 15). Note how despite excising upper eyelid skin, the repositioning of the upper eyelid crease at a lower level restores the (illusion) of volume to the upper periorbita.

Courtesy of Steven Fagien.

Figure 11-5 A, Preoperative appearance of a patient with unilateral right upper eyelid ptosis with associated dermatochalasis and herniated orbital fat of all four eyelids. B, After right Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis procedure with excision of upper eyelid skin without orbicularis oculi muscle excision and medial orbital fat combines with lower blepharoplasty using a skin flap approach and lateral retinacular suspension canthoplasty (see Chapter 15). Note again how despite excising upper eyelid skin, the repositioning of the right upper eyelid crease (via the Müller’s muscle ptosis surgery and upper blepharoplasty) at a lower level restores the illusion of volume to the upper periorbita to achieve symmetry.

Courtesy of Steven Fagien.

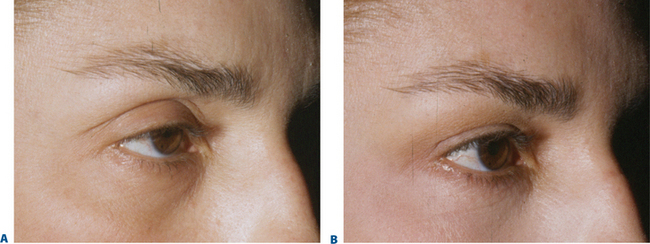

Figure 11-6 A, Preoperative appearance of a patient with bilateral upper eyelid ptosis (right much greater than left and the patient only perceives the ‘droop’ on the right side) with associated brow ptosis, dermatochalasis and herniated orbital fat of all four eyelids. The patient refused a brow lift. B, After right 4.0 mm Müller’s muscle–conjunctival resection–ptosis procedure with excision of upper eyelid skin without orbicularis oculi muscle excision and medial orbital fat combines with lower blepharoplasty using a skin flap approach and lateral retinacular suspension canthoplasty (see Chapter 15). Note again how despite excising upper eyelid skin, the repositioning of the right upper eyelid crease (via the Müller’s muscle ptosis surgery and upper blepharoplasty) at a lower level restores the illusion of volume to the upper periorbita to achieve symmetry. The appearance of improved upper periorbital volume by skin excision with orbicularis muscle preservation also reduced the worsening of the brow ptosis while improving the appearance of the upper eyelids.

Courtesy of Steven Fagien.

1 Putterman AM, Urist MJ. Müller’s muscle-conjunctival resection: Technique for treatment of blepharoptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:619.

2 Fraunfelder FT, Scafidi A. Possible adverse effect from topical ocular 10% phenylephrine. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:447-453.

3 Glatt HJ, Fett DR, Putterman AM. Comparison of 2.5% and 10% phenylephrine in the elevation of upper eyelids with ptosis. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:173.

4 Hildreth HR, Silver B. Sensory block of the upper eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;77:202-231.

5 Fagien S. Advanced rejuvenative upper blepharoplasty: enhancing aesthetics of the upper periorbita. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:278.

6 Putterman AM, Fett DR. Müller’s muscle in the treatment of upper eyelid ptosis: A ten-year study. Ophthalmic Surg. 1986;17:354-356.

7 Fasanella RM, Servat J. Levator resection for minimal ptosis: Another simplified operation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1961;65:493-496.

8 Putterman AM, Urist MJ. Müller’s muscle-conjunctival resection-ptosis procedure. Ophthalmic Surg. 1978;9:27-32.

9 Jones LT, Quickert MH, Wobig JL. The cure of ptosis by aponeurotic repair. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:629-634.