Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid

Introduction

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP), previously known as cicatricial pemphigoid, is a systemic cicatrizing autoimmune disease characterized by chronic blistering of mucous membranes, including ocular, oral, genital, nasopharyngeal, anogenital, and laryngeal mucosa, with ocular (60.1–80%) and oral (90.2%) involvement the most common.1 The disease causes subepithelial damage and excessive scar tissue formation, which can be life threatening if the trachea or esophagus is involved, or sight threatening if the eyes are involved. Cutaneous involvement is seen in approximately 20% of the patients and usually affects the head, neck, and upper trunk.2

Ocular MMP, also known as ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP), is seen as a progressive cicatrizing conjunctivitis, which, if left untreated, bears the risk of symblepharon, ocular surface diseases, corneal ulceration and neovascularization, and ankyloblepharon, causing visual impairment or blindness. It generally presents a chronic course, characterized by periods of activity subsequent to quiescent phases. In large series, approximately 80% of the patients with MMP have ocular involvement,3 and blindness has been reported to occur in 27%.4

Epidemiology

The incidence of MMP is approximately one new case per million inhabitants per year. MMP is considered a potentially fatal autoimmune disease with a mortality usually secondary to aero-digestive tract stricture formation, quoted as 0.028 per 100 000 in the United States during 1992–2002.5

OCP is a relatively rare disease with an estimated incidence of 1 in 15 000 to 1 in 60 000 ophthalmic patients.6 However, these studies do not report the true epidemiologic incidence of this disease because the reported cases are usually not in their earliest stages.3 Typical presentation involves a patient in the sixth or seventh decade of life, although it is recognized that OCP can begin at least as early as the third decade of life.7 In a study involving 130 patients, Foster et al. described that the average age was 64 years with a range of 20 years to 87 years. Females are affected two to three times as frequently as males. It has no racial or geographic predilection.3

Pathogenesis

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) is an autoimmune chronic cicatrizing conjunctivitis (CCC) associated with linear deposition of IgG and IgA aoutoantibodies directed against autoantigens at the conjunctival epithelial basement membrane zone (BMZ)3 that sets in motion a complex series of events. Bhol et al. concluded that a 205-kilodalton (KDa) protein molecule is the putative target antigen for OCP.8 Among others, the target antigen identified by the sera of patients with OCP is located in the basal epithelial cell hemidesmosome cytoplasmic domain of β4 subunit of the α6β4 integrin heterodimer.9 Autoantibodies are thought to cause scarring of the conjunctiva via activation of complement, neutrophils and proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, immunohistochemical study of the conjunctiva from patients with active OCP revealed significantly more T-helper-inducer cells (CD4+) and Langerhans cells in the epithelium and active T cells, fibroblasts and macrophages in the substantia propria compared to the control group.10 Staining for transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is also significantly increased.

Fibrosis results from the stimulation of fibroblasts, often by fibrogenic growth factors as TGF-β, PDGF, TNF and IL-1.11 When quiescent fibroblasts are stimulated to proliferate by these modulators, there is transient expression of proto-oncogenes, including c-fos, c-myc and c-myb. These are a series of genes that are transducers of external growth factors and probably trigger the activation of genes that are required for proliferation.

Several human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), including HLA-DR4 and HLA-DQw3 were first reported to be associated with increased susceptibility to the OCP.12 Furthermore, a prevalence of HLA-DQB1*0301 was first described in patients with pure ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid.13 This allele, however, was later found to be associated with all clinical sites of involvement and possibly to be linked to antibasement membrane IgG production. Interestingly, these studies also suggested a role for this allele in disease severity. Environmental triggers, such as microbial infection or drug exposure may stimulate the genetically susceptible individuals and induce the development of the disease.

Diagnosis

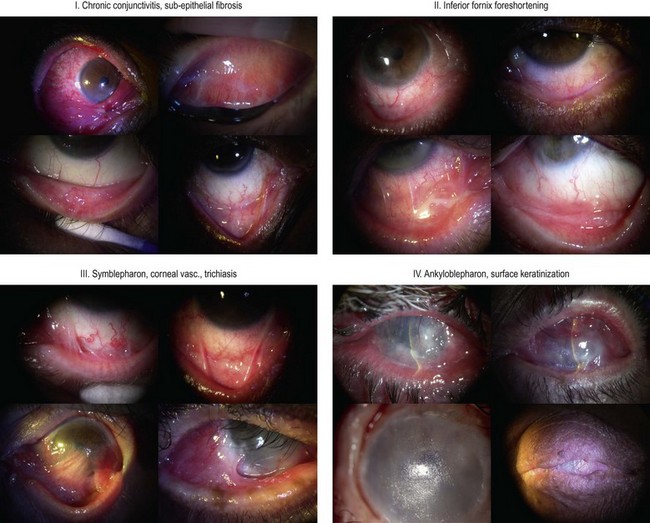

To assess the progression of the fibrotic process and treatment efficacy, it is important to quantify fibrosis and conjunctival inflammation. The classification of Foster et al. (Fig. 31.1) uses as an index the degree of inferior fornix foreshortening and the number and extension of symblephara.14 Subepithelial fibrosis is characteristic of stage I of OCP, with stage II showing fornix foreshortening. Symblepharon formation is the hallmark of stage III. Stage IV, end-stage disease, is characterized by ankyloblepharon and surface keratinization. Mondino’s classification quantifies inferior fornix depth loss.15 Stage II is a reduction of 25–50%; stage III, 50–75%; stage IV, more than 75%. Normal depth is approximately 11 mm.

Laboratorial Features

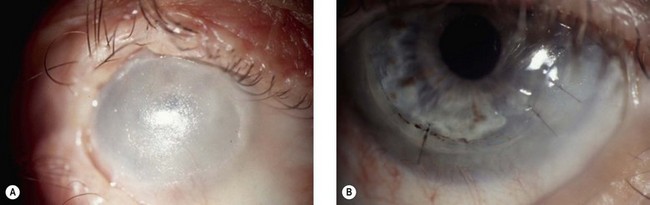

Direct Immunopathology

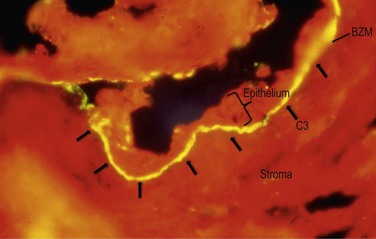

Direct methods of immunofluorescence microscopy or immunohistochemistry examinations on perilesional mucosa biopsies detect continuous deposits of any one or combination of the following in the epithelial BMZ: IgG, IgA, and/or C3 (Fig. 31.2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) evidence has been recommended as a mandatory requirement for the diagnosis of MMP.16 However, conjunctival DIF is positive in only 20–83% of cases of ocular MMP,17 and the results can be initially positive then subsequently negative, and vice versa, during the course of the disease, apparently unrelated to disease activity or treatment.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

Indirect immunofluorescence testing of patients’ serum using chemically separated normal human epithelial substrate is a sensitive method for detecting circulating autoantibodies to epithelial BMZ components in affected patients. Current assays that identify circulating autoantibodies have a limited role in serological diagnosis, since sensitivity is determined by substrate used; even the best available substrate yielded only a 52% positive result.18

More sensitive assays include the radioimmunoassay19 and immunoblot assay (IBA),8 and an ELISA assay for detection of such circulating autoantibodies is currently being developed.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of MMP includes other immunobullous diseases, erythema multiforme, lupus erythematosus, lichen planus, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Similar to OCP, many disorders may cause subepithelial fibrosis with or without inflammation (Box 31.1).20 OCP may represent the sequela of a prior bout of Stevens–Johnson syndrome, occurring a few months to as much as 30 years previously. Drug-induced cicatrizing or inflammatory conjunctivitis, also known as ocular pseudopemphigoid, can arise from long-term use of certain ophthalmologic preparations (antiviral and glaucoma medications) or biologic drugs (epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors).

Treatment

Inflammation resulting from systemic immune imbalance requires treatment with systemic immunosuppressive agents. Previous studies showed that almost 75% of the patients require systemic immunosuppression21 and 46% require continuing systemic treatment to avoid disease reactivation. There is no evidence that topical therapy alters the natural history of the disease.3

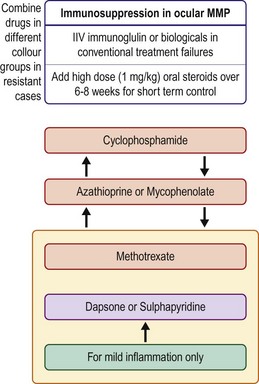

The immunosuppressive therapeutic approach should take into consideration the severity and the progression of the disease, the patient’s age, health and anticipated tolerance of treatment-related side effects, and the response to treatment (Fig. 31.3). For patients with severe disease or rapid progression of disease, the initial treatment should be with cyclophosphamide (1–2 mg/kg/day) and prednisone (1–1.5 mg/kg/day)22 for 6–8 weeks, and sometimes in conjunction with intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone (500 mg–1 g, up to three doses over 3 days). Because cyclophosphamide is associated with an increased risk of bladder carcinoma, the safe duration of treatment with this agent is limited to 12–18 months. Cyclophosphamide can also be administered intravenously if patients cannot tolerate the oral form. When the disease is controlled, prednisone administration should be slowly tapered while maintaining the immunosuppressive regimen for a longer period. In a preliminary study, intravenous immunoglobulin has been reported to be a safe and effective therapy for recalcitrant ocular disease23 or as an alternative to conventional immunosuppression. Monoclonal antibody therapies are potential treatments for severe refractory MMP.

Dry Eye

Several potential topical or systemic pharmacologic agents may stimulate aqueous secretion, mucous secretion, or both. The topical agents currently under investigation are diquafosol, rebamipide, gefarnate, ecabet sodium and 15(S)-HETE. Two orally administrated cholinergic agonists, pilocarpine and cevilemine, have been evaluated in clinical trials and were found to significantly improve symptoms of dryness and aqueous tear production. Salivary gland transplantation may also constitute an option for the treatment of severe dry eye secondary to OCP. This may be considered a step prior to limbal stem cell and corneal transplantation.24

Eyelid Abnormalities

Trichiasis is a common and potentially sight-threatening complication of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) and is the major risk factor for microbial keratitis. It may also cause punctate epitheliopathy, corneal abrasions, conjunctival metaplasia, provoke additional conjunctival inflammation, and increase ocular surface symptoms. It is usually secondary to cicatricial entropion and may involve either the upper or lower lid. Trichiasis can be treated with several methods: laser thermoablation, lid split through the gray line and anterior lamellar reposition, excision with oral mucous membrane or amniotic membrane transplantation or cryotherapy. Another option of protection against the trauma provoked by the eyelashes in contact to the conjunctiva and cornea is a scleral contact lens.25

Basenment Membrane Abnormalities

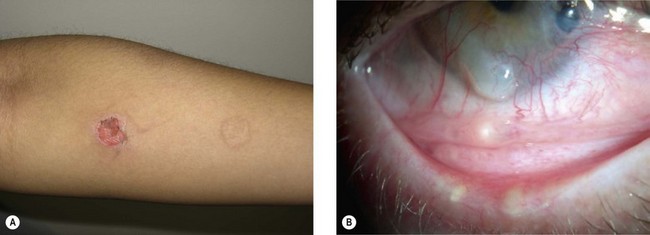

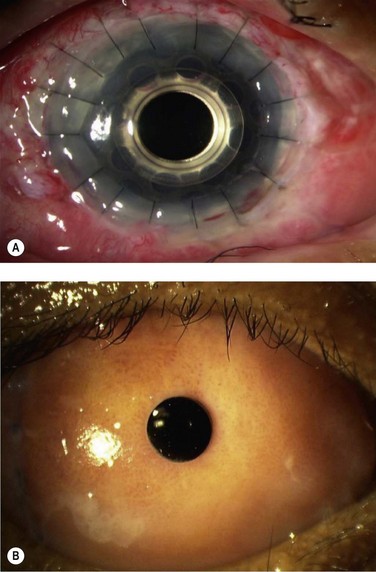

The complex autoimmune disorder with multiple components of the immune system participating in the OCP results in an inflamed conjunctiva at the BZM level with formation of bullae and scarring. Chronic conjunctivitis is the common cause of many complications of this disease. In order to establish control of the inflammation and maintain a stable conjunctiva, decreasing the symblepharon formation in patients with OCP, several studies have been performed using amniotic membrane transplantation (Fig. 31.4). It has unique properties that improve the pain, confer anti-inflammatory, antiadhesive and antiangiogenic effects, has the ability to stimulate re-epithelialization and lacks immunogenicity. Previous studies demonstrated that amniotic membrane can be used as an initial step in attempting to reconstruct the ocular surface in patients with advanced OCP.26

Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency

Tsubota et al. reported successful visual improvement in 9/9 eyes with use of limbal allografts and amniotic membrane transplantation in conjunction with systemic immunosuppression with dapsone and cyclosporine. Penetrating keratoplasty was also performed in 5 of the 9 eyes.26 Other reports of the outcomes of surface reconstructive surgery that used living-related limbal allografts27 or cultivated epithelial stem cells28 describe results for only two or three OCP eyes. Once ocular surface inflammation and progression have been controlled, attention can be turned to other means of improving vision (Fig. 31.5).

When ocular surface reconstruction and penetrating keratoplasty fail, keratoprosthesis (KPro) surgery may provide the only potential means of restoring vision in patients with progressive OCP (Fig. 31.6). However, transcorneal KPros, such as the Boston type I device have shown limited results in the long-term follow-up of advanced OCP patients with severe dry eye. This device carries a guarded prognosis in OCP due to the high risk of corneal melting and device extrusion. Boston type II KPros or the osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP) devices appear to be better options for these cases of OCP in comparison to the Boston type 1 device.29

References

1. Thorne, JE, Anhalt, GJ, Jabs, DA. Mucous membrane pemphigoid and pseudopemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:45–52.

2. Williams, GP, Radford, C, Nightingale, P, et al. Evaluation of early and late presentation of patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid to two major tertiary referral hospitals in the United Kingdom. Eye (Lond). 2011;25:1207–1218.

3. Foster, CS. Cicatricial pemphigoid. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;84:527–663.

4. Hardy, KM, Perry, HO, Pingree, GC, et al. Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:467–475.

5. Risser, J, Lewis, K, Weinstock, MA. Mortality of bullous skin disorders from 1979 through 2002 in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1005–1008.

6. Lever, WF, Talbott, JH. Pemphigus: a historical study. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1942;46:800.

7. Kharfi, M, Khaled, A, Anane, R, et al. Early onset childhood cicatricial pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:119–124.

8. Bhol, K, Mohimen, A, Neumann, R, et al. Differences in the anti-basement membrane zone antibodies in ocular and pseudo-ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Curr Eye Res. 1996;15:521–532.

9. Bhol, KC, Dans, MJ, Simmons, RK, et al. The autoantibodies to alpha 6 beta 4 integrin of patients affected by ocular cicatricial pemphigoid recognize predominantly epitopes within the large cytoplasmic domain of human beta 4. J Immunol. 2000;165:2824–2829.

10. Rice, BA, Foster, CS. Immunopathology of cicatricial pemphigoid affecting the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1476–1483.

11. Muller, R, Bravo, R, Burckhardt, J, et al. Induction of c-fos gene and protein by growth factors precedes activation of c-myc. Nature. 1984;312:716–720.

12. Zaltas, MM, Ahmed, R, Foster, CS. Association of HLA-DR4 with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:189–193.

13. Ahmed, AR, Foster, S, Zaltas, M, et al. Association of DQw7 (DQB1*0301) with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci UA. 1991;88:11579–11582.

14. Foster, CS, Wilson, LA, Ekins, MB. Immunosuppressive therapy for progressive ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:340–353.

15. Mondino, BJ, Ross, AN, Rabin, BS, et al. Autoimmune phenomena in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83:443–450.

16. Chan, LS, Ahmed, AR, Anhalt, GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:370–379.

17. Tauber, J, Jabbur, N, Foster, CS. Improved detection of disease progression in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Cornea. 1992;11:446–451.

18. Power, WJ, Neves, RA, Rodriguez, A, et al. Increasing the diagnostic yield of conjunctival biopsy in patients with suspected ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1158–1163.

19. Ahmed, AR, Khan, KN, Wells, P, et al. Preliminary serological studies comparing immunofluorescence assay with radioimmunoassay. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:1011–1019.

20. Saw, VP, Dart, JK. Ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid: diagnosis and management strategies. Ocul Surf. 2008;6:128–142.

21. Elder, MJ, Bernauer, W, Leonard, J, et al. Progression of disease in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:292–296.

22. Elder, MJ, Lightman, S, Dart, JK. Role of cyclophosphamide and high dose steroid in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:264–266.

23. Sami, N, Letko, E, Androudi, S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients with ocular-cicatricial pemphigoid: a long-term follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1380–1382.

24. Sant’ Anna, AE, Hazarbassanov, RM, de Freitas, D, et al. Minor salivary glands and labial mucous membrane graft in the treatment of severe symblepharon and dry eye in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;96:234–239.

25. Siqueira, AC, Santos, MS, Farias, CC, et al. [Scleral contact lens for ocular rehabilitation in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome]. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73:428–432.

26. Tsubota, K, Satake, Y, Ohyama, M, et al. Surgical reconstruction of the ocular surface in advanced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:38–52.

27. Santos, MS, Gomes, JA, Hofling-Lima, AL, et al. Survival analysis of conjunctival limbal grafts and amniotic membrane transplantation in eyes with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:223–230.

28. Nishida, K, Yamato, M, Hayashida, Y, et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1187–1196.

29. Dohlman, CH, Terada, H. Keratoprosthesis in pemphigoid and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:1021–1025.