11 Motor neurone disease

Introduction

Incidence

The incidence is about 2 per 100 000, with a familial form found in about 1% of all cases [1]. MND tends to be a disease of later middle life; the mean age of onset is 58 years, with a slightly higher percentage of males affected.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

This is the most common form of MND, accounting for about 66% of all patients [2], with both upper and lower motor neurones affected. It is characterized by weakness and wasting in the limbs, often first indicated by clumsiness in walking or handling things. Most commonly the upper limbs and hands are affected first with evident wasting of the thenar eminence. Average life expectancy with this form can be between 2 and 5 years from onset of symptoms.

Progressive bulbar palsy (PBP)

Wild mood swings may also occur with little apparent cause. The limbs are less affected but as the disease progresses the patient may experience weakness in the arms and legs [3]. Life expectancy is between 6 months and 3 years from the onset of symptoms.

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA)

Although ALS, PBP and PMA are the three main forms of MND there is an enormous variation in symptoms between patients. Control of bladder or bowels is rarely affected. Mental deterioration and dementia are found in less than 5% of patients [3]. There is increasing evidence of frontal lobe involvement which may lead to emotional lability. Anxiety and depression are quite commonly found, unsurprisingly, in such a serious disease.

Prognosis

Impact on the patient

The manifest problems can be subdivided into the following categories.

Pain

This is a common problem, with up to 73% of patients reporting pain of some kind [4]. The causes are mainly muscular, muscle cramps, spasticity or spasms as a result of weakening muscles. These produce abnormal stresses on the joints and often result in changed posture, leading to further stresses and pain. If the patient is unable to change position easily then areas of pressure will also lead to pain. Chronic back pain produced by poor posture is very common.

Insomnia

This is a common problem, reported in 48% of patients admitted to a hospice [5]. There are of course many reasons why this might be so. Firstly, any breathlessness will tend to get worse when it is time to sleep, especially if there is associated anxiety. Again, this is often linked to weak musculature. It may also be associated with depression and may respond to antidepressants or sedatives.

MND and physiotherapy

The pain can be dealt with in several ways. As discussed previously, a lot of it is due to the weakening of muscle, the imbalance caused by this and the subsequent inappropriate increase in muscle tone, leading to cramps and spasticity. Correct positioning, education of handlers in moving and handling and encouragement of physiological movement with adequate rest periods underpin the treatment programme. Gentle stretching to maintain soft-tissue length can sometimes alleviate pain. Acupuncture may also now be routinely considered as part of the pain relief [6]. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), hot packs or even warm baths can all be useful.

Acupuncture in MND

There is not much evidence supporting the use of acupuncture in MND, or ALS. This is surprising considering the manifestations of the disease but probably reflects the overall rarity of the condition. It is possible that much of the recorded acupuncture research on patients receiving palliative care does include a fair number of MND sufferers. Specific problems, such as anxiety, depression, insomnia and shortness of breath, are fairly common in this unfortunate group [7]. The calming and anxiolytic effect of acupuncture will contribute significantly in this situation.

A recent Cochrane review included five acupuncture studies and decided that there was low evidence that acupuncture and acupressure were useful [8]. Acupuncture certainly is used [9], but precise details of the interventions are often lacking.

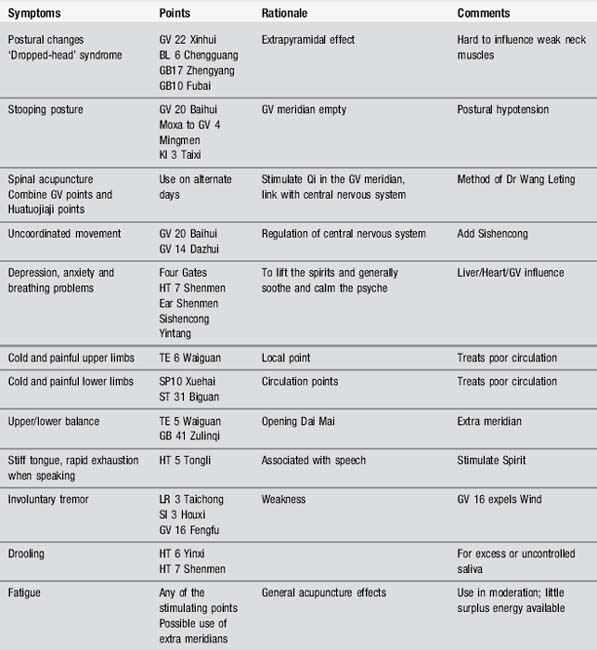

Body acupuncture

Local points are used in dealing with the pain to facilitate freer joint movement; a concentration on the major Yang meridians will be helpful, with the addition of the powerful distal points. The limbs are thought to be regulated through the Governor Vessel so acupuncture can be used to strengthen and augment the flow of Qi which may be blocked by pathogenic invasion. Table 11.1 offers a selection of useful points.

Scalp acupuncture

Some authorities use scalp acupuncture but MND is not generally cited as an indication. However Jiao suggests that two variations of bulbar paralysis will respond [10]. What he terms as ‘true bulbar paralysis’ with symptoms of dyslalia, dysphagia and the disappearance of the pharyngeal reflex can be treated by stimulating the balance areas bilaterally. What he terms ‘false bulbar paralysis’, with additional symptoms of dysphagia, choking and excess salivation, requires the addition of the lower two-fifths of the motor area on each side (see Chapter 12). Good results are claimed, but there is no very convincing research evidence as yet.

TCM approach

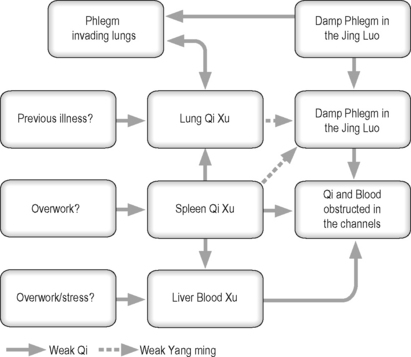

Nicholas Haines provides a good example of a case history in the book Acupuncture in Practice [11]. In a useful flow diagram (Figure 11.1) he indicates how a succession of pathogenic influences may produce the right circumstance for the symptoms of MND. It is not suggested that these are the root cause of the disease but the TCM points to treat them will be useful as part of the wider management of the patient.

Figure 11.1 An example of generation of motor neurone disease in traditional Chinese medicine terms.

(After Haines [11].)

Case study 11.2: level 2 case

The patient, aged 65, had had MND for 4 years and was now in the terminal phase.

The aim of treatment was to clear phlegm, improve lung function and reduce anxiety.

Treatment 1

Acupuncture was given to ST 40, LU 5, LI 4 bilaterally and CV 17 for 20 minutes.

Case study 11.3: level 3 case

Treatment 2

The acupuncture extended to address her psychological status as well as her painful areas

[1] Borasio G.D., Miller R.G. Clinical characteristics and management of ALS. Semin Neurol. 2001;21(2):155-166.

[2] Stokes M. Physical Management in Neurological Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby, 2006.

[3] Tandan R. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of classical motor neurone disease. In: Williams A.C., editor. Motor Neurone Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1994:3-27.

[4] Oliver D. The quality of care and symptom control – the effects on the terminal phase of ALS/MND. J Neurol Sci. 1996;139(Suppl):134-136.

[5] O’Brien T., Kelly M., Saunders C. Motor neurone disease: a hospice perspective. BMJ. 1992;304(6825):471-473.

[6] Wasner M., Klier H., Borasio G.D. The use of alternative medicine by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;191(1–2):151-154.

[7] Molassiotis A., Sylt P., Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15(4):228-237.

[8] Bausewein C., Booth S., Gysels M., et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2008.

[9] Vardeny O., Bromberg M.B. The use of herbal supplements and alternative therapies by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). J Herb Pharmacother. 2005;5(3):23-31.

[10] Jiao S. Scalp Acupuncture and Clinical Cases. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1997.

[11] Haines N. Treating the untreatable. In: MacPherson H., Kaptchuk T., editors. Acupuncture in Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:83-92.