Modified Osteo-Odonto-Keratoprosthesis

MOOKP

Introduction

Corneal transplantation has revolutionized the treatment of corneal blindness. Corneal allografts into non-inflamed recipients with a healthy ocular surface (e.g. keratoconus) offers a survival rate of > 80% at 5 years under optimal conditions.1 This high anatomical allograft survival doesn’t apply to patients with corneal blindness that is associated with an inflamed ocular surface and/or vascularized cornea, such as autoimmune disease (ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnson syndrome) and limbal stem cell deficiency (aniridia, severe chemical burns). Corneal allografts in these situations have a poor prognosis, with graft survival rates of less than 25%.2 According to the World Health Organization, corneal blindness is the fourth most common cause of blindness in the industrialized world and the second most common cause of blindness in the developing world. The majority of these cases occur in the setting of end-stage ocular surface disease.3 There has been a need for a safer and effective alternative to corneal allografts. Guillaume Pellier de Quengsy initiated the idea of designing a keratoprosthesis as an alternative to corneal allograft.4 Currently, the three most common keratoprosthetic devices are the Boston Keratoprosthesis (KPro™), the AlphaCor™ artificial cornea and the osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP).5

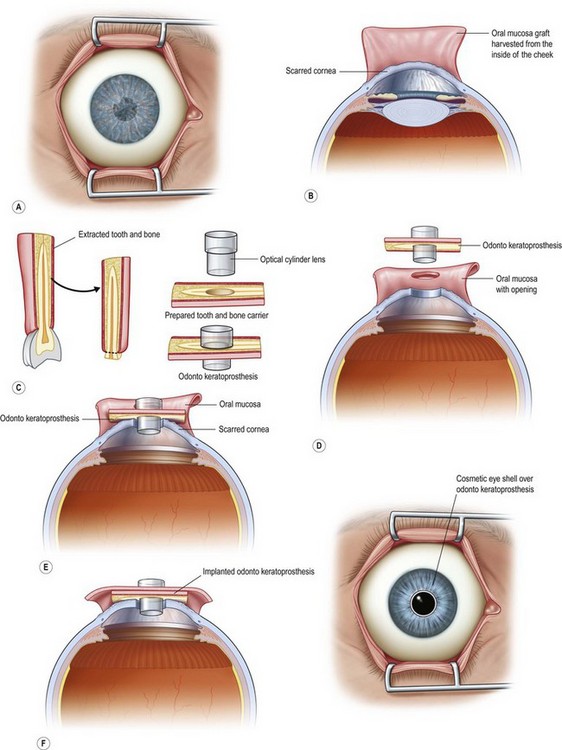

The OOKP was developed more than 45 years ago. The basic concept of this keratoprosthesis is to use the patient’s own tissue (heterotopic autograft of patient’s own tooth root and alveolar bone) to support an optical cylinder of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), thereby significantly reducing the possibility of an immunogenic response against foreign tissue. Having autologous living material supporting the optical cylinder decreases the chance of prosthesis extrusion and offers long-term stability to the optical cylinder. The OOKP is conformed by the patient’s own tooth root and alveolar bone that are fashioned into a lamina that supports a PMMA optical cylinder. The device is covered by mucosa (preferably buccal mucosa) to offer a layer of protection from a hostile environment, such as a keratinized ocular surface (Fig. 53.1). Currently, the OOKP designed by Strampelli and modified by Falcinelli (MOOKP) is the keratoprosthesis with best visual outcomes and proven long-term follow-up to restore sight in patients with end-stage ocular surface disease.6

MOOKP Indications and Preoperative Considerations

The MOOKP is indicated for patients with bilateral corneal blindness and associated end-stage ocular surface disease, severe vascularization of the cornea and/or end-stage limbal stem cell deficiency (Box 53.1). Relative and absolute contraindications for the OOKP surgery are listed in Table 53.1.

Table 53.1

| Absolute Contraindications | Relative Contraindications |

| Pediatric patients, due to the high rate of bone reabsorption | Defective light perception, especially in the setting of known advanced glaucoma. |

| Phthisis bulbi | Patient unable or refusing to have close clinical follow-up |

| Eyes with no light perception | |

| Eyes with inoperable retinal detachment or a severely damaged posterior segment. | |

| Unrealistic visual and/or cosmetic expectations |

Surgical candidates for MOOKP need to have an extensive ophthalmic and medical evaluation. Evaluation includes the estimation of potential visual acuity, detailed slit lamp examination, ultrasound biomicroscopy, A-scan biometry and digital or mechanical estimation of intraocular pressure. The cornea surgeon should evaluate the eye in collaboration with a glaucoma surgeon to detect the possibility of preoperative glaucoma, and to determine a medical and/or surgical treatment strategy for either current or future glaucoma management. Approximately 50% of all patients who require a keratoprosthesis have a pre-existing diagnosis of secondary glaucoma and progressive optic nerve damage from glaucoma, which is the most common cause of vision loss in patients with MOOKP.7

Visual evoked potential (VEP) and electroretinography (ERG) can be used in the preoperative evaluation to obtain a more objective estimate of the potential visual acuity. The use of these tests is not absolutely necessary, but studies have shown that eyes demonstrating normal ERG or VEP achieved better visual outcomes than those with abnormal test results.8

A detailed evaluation of the patient’s oral mucosa and the overall oral cavity health needs to be performed prior to the MOOKP. Orthopantomography and X-ray of the tooth are mandatory, and the use of spiral computerized tomography (CT) is helpful. The healthiest tooth with the largest root is chosen for the harvesting step. According to Falcinelli et al.,6,9 the preferred choice for the tooth, in descending order of usefulness, is the upper canine, inferior canine, bother upper incisors, first or second upper premolar, first and second inferior premolar and inferior incisors. In cases of poor oral health, where it is not possible to harvest a healthy tooth, an allograft from a living relative is considered. This will mandate the use of systemic immunosuppression. Before making the decision to proceed with an allograft, the patient needs to understand the risk of immunosuppressive treatment and know that the long-term outcomes are not equal to the standard procedure.

Surgical Technique

The Rome–Vienna Protocol was published under the leadership of Professor Falcinelli in 2005. This surgical protocol serves as the gold standard for OOKP surgery and provides a detailed description of the surgical technique.9 Our group strictly follows this protocol (Fig. 53.2).

The MOOKP has two major surgical stages. Stage 1 involves the preparation of the globe, mucosa and the osteo-odonto lamina. Stage 2 involves the implantation of the osteo-odonto lamina. Both surgical stages require general anesthesia. It is an absolute requirement that the patient receives a pre-anesthetic evaluation. Patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) frequently suffer from oropharyngeal mucosal erosions, scarring, and strictures, all of which can cause a difficult intubation. Surgical stage 1 can be managed with nasotracheal or orotracheal intubation and stage 2 with orotracheal intubation.10

Stage 1

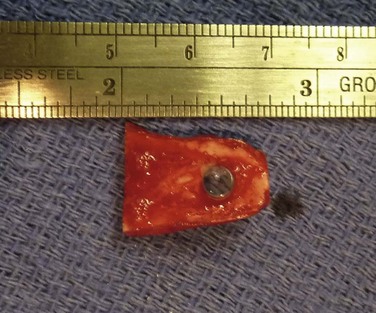

Preparation of the Lamina

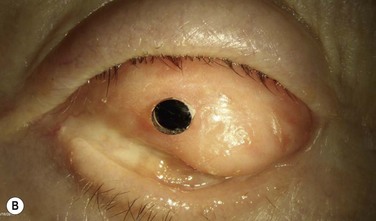

This step should be done in collaboration with an oral and maxilofacial surgeon (OMFS). Under general anesthesia, the oral cavity is rinsed with povidone-iodine. Using a bone saw, the root and surrounding alveolar bone are removed. It is important to preserve the periosteum of the bone as this will cover the bone of the implant in a later stage. The recommended size of the dento–alveolar lamina is about 15 mm in length and 10 mm of the former labiopalatinal dimension. After removing half of the root, the lamina should have a thickness of 3.5 mm (no less than 3.0 mm). During the grinding procedure, the lamina should be irrigated. In order to avoid damage to the dento-alveolar ligament, manipulation of the lamina is achieved by grasping the crown. The next step is to remove half of the root from the former temporal or medial side of the alveolar bone with a diamond-coated flywheel. The drilling of the hole for the cylinder should be centered on the dentine, leaving at least 1 mm of dentine on either side of the cylinder. The hole should be perpendicular to the plane of the dentine to avoid tilting of the optical cylinder. The dimensions of the optical cylinder can vary.11 Our group follows the recommendations by Falcinelli and his team. In order to hold the cylinder in position during cementing, the diameter of the posterior part should be around 0.3 mm larger than the anterior part. It is crucial that the cementing is done with a dry surface. Using the flywheel, the crown of the tooth is removed and the implant is rinsed in povidone-iodine. Next, the crown is soaked in antibiotic solution and inserted into a subcutaneous pouch (Fig. 53.3). The implant will remain there for approximately 3 months, allowing enough time to promote revascularization of the implant and growth of the periosteum. The OOAL should be inserted with the dentine facing the orbit and the bone toward the periorbital muscle. The wound healing process involves careful monitoring for any signs of infection (Fig. 53.4).

Stage 2

This stage of the procedure is scheduled 3 months after the implantation of the OOAL. The mucosal graft should be completely integrated to the ocular surface with no signs of necrosis. Under sterile conditions, the lamina is removed from the subcutaneous space and carefully inspected for any signs of significant bone reabsorption. The OOAL is explanted and the connective tissue is removed. Next, the mucosa covering the ocular surface is excised superiorly and lifted from the ocular surface with creation of a partial flap that remains attached inferiorly. A Flieringa ring is sutured to the sclera and traction sutures are placed 180° apart. These sutures are used to lift the ring at the time of insertion of the lamina. The center of the cornea is located and then trephined. Facinelli et al. recommend complete removal of the iris, lens and anterior vitreous if still present.6,9 Three radial incisions of the cornea are performed to give exposure. For the lens removal an intracapsular or extracapsular technique can be performed.5 The implant is placed by pulling of the traction sutures attached to the Flieringa ring. The radial incisions are sutured for closure. Filtered air or balanced salt solution can be injected to pressurize the eye. The implant is fixed with interrupted nylon sutures. The back part of the implant should be in contact with the cornea and no connective tissue should be left within the area. With the use of indirect ophthalmoscopy, the centration of the cylinder in relation to the fovea is carefully examined. The Flieringa ring is removed. The final step is to reflect back the mucosa and perform a central trephination to expose the anterior surface of the optical cylinder. The mucosa is then sutured to the episclera and conjunctiva.

Visual and Anatomical Outcomes after MOOKP

Facinelli’s group has the largest series of patients with the longest follow-up.9 Their latest report included 224 patients with an anatomical success of 94% with a median follow-up of 9.4 years, with some patients with over 25 years of follow-up. This report offers the longest follow-up available for any type of keratoprosthesis. From another report, Falcinelli et al. showed that from the 224 patient series a total of 181 patients were chosen because these patients follow the exact same surgical protocol. Survival analysis estimated that 18 years after the surgery, the probability of retaining an intact prosthesis was 85%. Mean best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) varied from 0.41 Log Mar (patients with bullous keratopathy following glaucoma surgery) to 0.8 Log Mar (patient with corneal burns and dry eye syndrome).6

Another report from India of 50 cases with a mean follow-up of 15.38 months (range of 1 to 58 months) showed an anatomical success similar to the group in Italy with a mean BCVA of > 20/60 in 66% of the patients. Only five patients had a decrease in vision after the OOKP surgery.12 The Asian MOOKP group reported the results of 16 patients with a mean follow-up of 19.1 months (range 5–31 months). The anatomical success was favorable in 15 of the 16 patients. One patient with a history of multiple glaucoma procedures had an expulsive choroidal hemorrhage at the time of stage 2. Eleven of the 15 patients with anatomical success obtained a BCVA of at least 20/40.13 The first MOOKP performed in the United States was in 2009, on a patient blinded by Steven–Johnson syndrome.14,15 The surgical procedure was a success and the clinical outcome after 2 years of follow-up is comparable to other published series, with a BCVA of 20/25. No complications have developed to date. Three additional patients have undergone one of more stages of MOOKP to date at the same facility.

Surgical Complications of MOOKP

MOOKP Stage 1 Intraoperative and Early Postoperative Complications

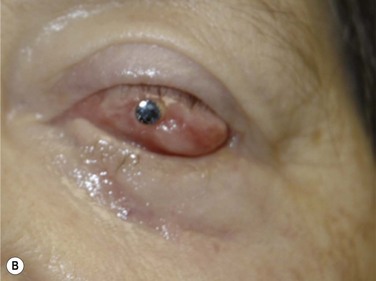

Complications related to the preparation of the globe include the possibility of perforation of the globe during the suturing process. If the perforation cannot be repaired with sutures, a patch graft should be performed in order to avoid hypotony and endophthalmitis. Close observation of the mucosa during the early postoperative period is important to identify cases of necrosis. If a high suspicion for necrosis develops, the mucosa should be cultured in order to rule out an infectious process (Fig. 53.5).

Late Postoperative Complications

The OOAL and the mucosa function is an excellent barrier against microorganisms, and this explains the low rate of endophthalmitis, compared to other keratoprosthetic devices.16,17 Falcinelli et al. reported endophthalmitis in 2.2% of a series of 181 patients.6,17 The Brighton series reported two cases of endophthalmitis in a retrospective review of 35 consecutive MOOKP surgeries.17 In cases of endophthalmitis, the recommendation is to lift the mucosa, remove the implant, perform a full vitrectomy, and deliver intravitreal antibiotic injections with broad-spectrum antibiotics. The treatment requires the use of a temporary keratoprosthesis. The eye should then be closed with a corneal graft and refixation of the mucosa with sutures.

Glaucoma

As previously mentioned, a high number of patients who require MOOKP surgery for visual rehabilitation have already had the diagnosis of glaucoma. For this reason, the intraocular pressure should be optimized when possible before stage 1 or stage 2 surgeries. The use of glaucoma drainage devices (GDD) is the preferred surgical technique. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) has also been used as an alternative to GDD. There are no long-term reports of safety in the use of ECP for MOOKP surgery and serious complications have already been reported.18 It is the recommendation of the Rome–Vienna protocol to use GDD as the first option in the management of high intraocular pressure and to avoid placing the GDD during stage 2 surgery. Due to the significant changes in the anatomy of the anterior segment after stage 2 surgery there is a potential for secondary glaucoma. The intraocular pressure should be monitored closely with digital palpation. If the intraocular pressure increases and cannot be controlled with topical or systemic medication or if optic nerve damage is confirmed (visual field testing or optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the nerve fiber layer), a GDD should be implanted.19

Retinal Detachment

The risk of retinal detachment (RD) according to Falcinelli’s group is around 5%.6,9 In 2008, the Brighton group reported a rate of 14% with five of 35 patients developing RD in their case series. Three were rhegmatogenous RD and two were secondary to endophthalmitis.17 Successful repair is possible with the use of a BIOM system or lifting the mucosa and placing a temporary keratoprosthesis. A scleral buckling procedure can be useful for repair, but additional intraocular retinal surgery is likely required, including the need for gas tamponade and/or silicone oil placement.20

References

1. Rahman, I, Carley, F, Hillarby, C, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty: indications, outcomes, and complications. Eye (Lond). 2009;23:1288–1294.

2. Tugal-Tutkun, I, Akova, YA, Foster, CS. Penetrating keratoplasty in cicatrizing conjunctival diseases. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:576–585.

3. Whitcher, JP, Srinivasan, M, Upadhyay, MP. Corneal blindness: a global perspective. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:214–221.

4. Mannis, MJ. Corneal transplantation. Western J Med. 1984;140:270.

5. Liu, C, Paul, B, Tandon, R, et al. The osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP). Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20:113–128.

6. Falcinelli, G, Falsini, B, Taloni, M, et al. Modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis for treatment of corneal blindness: long-term anatomical and functional outcomes in 181 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1319–1329.

7. Netland, PA, Terada, H, Dohlman, CH. Glaucoma associated with keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:751–757.

8. de Araujo, AL, Charoenrook, V, de la Paz, MF, et al. The role of visual evoked potential and electroretinography in the preoperative assessment of osteo-keratoprosthesis or osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 19, 2011.

9. Hille, K, Grabner, G, Liu, C, et al. Standards for modified osteo-odontokeratoprosthesis (OOKP) surgery according to Strampelli and Falcinelli: the Rome–Vienna Protocol. Cornea. 2005;24:895–908.

10. Garg, R, Khanna, P, Sinha, R. Perioperative management of patients for osteo-odonto-kreatoprosthesis under general anaesthesia: a retrospective study. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:271–273.

11. Hull, CC, Liu, CS, Sciscio, A, et al. Optical cylinder designs to increase the field of vision in the osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238:1002–1008.

12. Iyer, G, Pillai, VS, Srinivasan, B, et al. Modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis – the Indian experience–results of the first 50 cases. Cornea. 2010;29:771–776.

13. Tan, DT, Tay, AB, Theng, JT, et al. Keratoprosthesis surgery for end-stage corneal blindness in Asian eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:503–510. [e3].

14. Parel, JM, Sweeney, D. OOKP. Cornea. 2005;24:893–894.

15. Sawatari, Y, Perez, VL, Parel, JM, et al. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ role in the first successful modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis performed in the United States. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1750–1756.

16. Nouri, M, Terada, H, Alfonso, EC, et al. Endophthalmitis after keratoprosthesis: incidence, bacterial causes, and risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:484–489.

17. Hughes, EH, Mokete, B, Ainsworth, G, et al. Vitreoretinal complications of osteoodontokeratoprosthesis surgery. Retina. 2008;28:1138–1145.

18. Lee, RM, Al Raqqad, N, Gomaa, A, et al. Endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation in osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP) eyes. J Glaucoma. 2011;20:68–69.

19. Kumar, RS, Tan, DT, Por, YM, et al. Glaucoma management in patients with osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (OOKP): the Singapore OOKP Study. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:354–360.

20. Ray, S, Khan, BF, Dohlman, CH, et al. Management of vitreoretinal complications in eyes with permanent keratoprosthesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:559–566.